Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

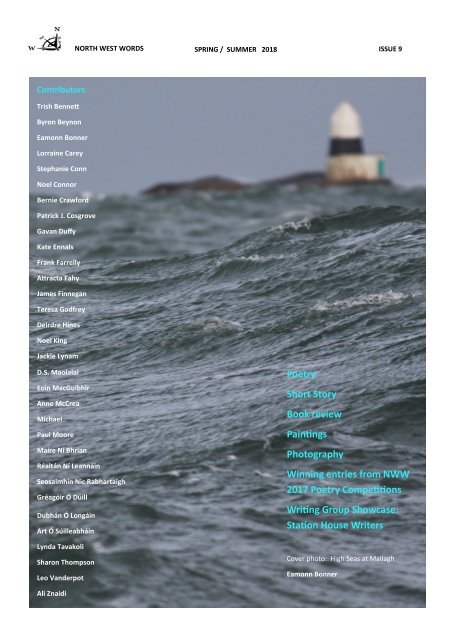

NORTH WEST WORDS SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Contributors<br />

Trish Bennett<br />

Byron Beynon<br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

Stephanie Conn<br />

Noel Connor<br />

Bernie Crawford<br />

Patrick J. Cosgrove<br />

Gavan Duffy<br />

Kate Ennals<br />

Frank Farrelly<br />

Attracta Fahy<br />

James Finnegan<br />

Teresa Godfrey<br />

Deirdre Hines<br />

Noel King<br />

Jackie Lynam<br />

D.S. Maolalai<br />

Eoin MacGuibhir<br />

Anne McCrea<br />

Michael<br />

Paul Moore<br />

Maire Ní Bhrian<br />

Réaltán Ní Leannáin<br />

Seosaimhín Nic Rabhartaigh<br />

Gréagóir Ó Dúill<br />

Dubhán Ó Longáin<br />

Art Ó Súilleabháin<br />

Lynda Tavakoli<br />

Sharon Thompson<br />

Leo V<strong>and</strong>erpot<br />

Poetry<br />

Short Story<br />

Book review<br />

Paintings<br />

Photography<br />

Winning entries from <strong>NWW</strong><br />

2017 Poetry Competitions<br />

Writing Group Showcase:<br />

Station House Writers<br />

Cover photo: High Seas at Mallagh<br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

Ali Znaidi

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Editorial 4-5<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

Photographs<br />

Painting: Lucky Shell Beach, Ards Forest , Creeslough, Co.<br />

Donegal<br />

North West Words <strong>and</strong> Donegal Creameries Poetry<br />

Competition 2017<br />

6<br />

7<br />

Noel Connor Damaged Tins 8-9<br />

Trish Bennett Galway Crystal 10<br />

Stephanie Conn Still Life in L<strong>and</strong>scape 11<br />

Patrick J. Cosgrove Euphemasia 12<br />

Gavan Duffy Keeper 13-14<br />

Frank Farrelly Rivers of Sleep 15<br />

James Finnegan I was in Lanesborough today 16<br />

Eamonn Bonner Photo: Passing Rutl<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> 16<br />

Noel King Way to Engl<strong>and</strong> 17<br />

Eoin MacGuibhir Séan Dáiliocht 18<br />

Lynda Tavakoli Dead Dog 19<br />

Lorraine Carey Painting: Solitude on Downhill Str<strong>and</strong>, Co.Derry 20<br />

Photograph<br />

North West Words <strong>and</strong> Ealáin na Gaeltachta Irish<br />

Language Poetry Competition 2017<br />

21<br />

Art Ó Súilleabháin Gur fút is breá liom 22-23<br />

Gréagóir Ó Dúill An Mhucais faoin Nollaig 24<br />

Maire Ní Bhriain An Dá Thrá 25<br />

Seosaimhín Nic Rabhartaigh Linntreoga Doimhne 26-27<br />

Dubhán Ó Longáin Ar Bhruach 28<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

Painting: Sea Mist over Glashedy Rock, Ballyliffin,<br />

Co. Donegal<br />

29<br />

D.S. Maolalai Humber River Hospital 30-32<br />

Eamonn Bonner Photo: High Flier - Seagull 32<br />

D.S. Maolalai For Melissa, in another country 33<br />

Attracta Fahy Philemelos 34<br />

Teresa Godfrey Sudden Death 35<br />

2

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Bernie Crawford Metamorphosis 36<br />

Ali Znaidi That Magic Within 37<br />

Sharon Thompson The Healer 38-40<br />

Michael A Secret 41<br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

Photo: Bronze Statue Hiring Fair Boy, Market Square,<br />

Letterkenny<br />

41<br />

Anne McCrea The Visit 42<br />

Kate Ennals What Word Would You Choose to Be? 43<br />

Leo V<strong>and</strong>erpot Note Left on a Librarian’s Desk 43<br />

Jackie Lynam Timing 44<br />

Paul Moore The Librarian 45-48<br />

Teresa Godfrey<br />

Reflection on Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Self-<br />

Portrait<br />

49<br />

Byron Beynon Roots 50<br />

Réaltán Ní Leannáin Ait 51<br />

Séan Golden Lel<strong>and</strong> at Cloonagh 52<br />

Miriam Nic Lochlainn Redemption 53-57<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

Deirdre Hines<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

Painting: Stonewall Secrets, Greencastle’s ruins,<br />

Co. Donegal<br />

Review: ‘You've never seen a doomsday like it’ by Kate<br />

Garrett<br />

Painting: Brooding Skies over Benevenagh, Magilligan,<br />

Co. Derry<br />

57<br />

58-61<br />

62<br />

Station House Writers Writing Group Showcase 63<br />

Eamonn Bonner Fanad, The House <strong>and</strong> The Lighthouse 63<br />

Ann Marie Gallagher What if Winter 64<br />

Michael Forde Cuban Crisis, I Corrib 65-67<br />

Eamonn Bonner Photo: Taking in the View: The Back Str<strong>and</strong>, Falcarragh 67<br />

Guy Stephenson Flicker 68-70<br />

Joe Lynch Avoiding Cliches 71<br />

Eamonn Bonner Roches Point Automatic 72<br />

Biographies 73-76<br />

Lorraine Carey Painting: Stormy Seas -Dunaff Head, Co. Donegal 77<br />

Eamonn Bonner Photo: Blue Ripple 78<br />

3

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Editorial<br />

Welcome to the <strong>Spring</strong>/<strong>Summer</strong> issue of the North West Words magazine. We are delighted to<br />

bring you another edition filled with 34 poems <strong>and</strong> 5 short stories from Irel<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> beyond. At the<br />

end of 2017, North West Words ran two adult poetry competitions - one in English <strong>and</strong> one in Irish.<br />

This issue proudly presents the shortlisted <strong>and</strong> winning poems from both of those competitions.<br />

Ten English language poems were shortlisted by poet Kate Newmann, with the overall winner<br />

announced at our January award night: Noel Connor’s poem “Damaged Tins”. Five Irish language<br />

poems were shortlisted by poet <strong>and</strong> fiction writer Proinsias Mac ’Bhaird, with the overall winner<br />

announced at our February award night: Art Ó Súilleabháin’s “Gur fút is breá liom”. Congratulations<br />

to all the shortlisted poets, <strong>and</strong> we hope our readers enjoy, as much as we did, the many voices of<br />

our competition poetry.<br />

Also featured are editors’ selections from our open submissions of both poetry <strong>and</strong> fiction, a new<br />

review section by Deirdre Hines, <strong>and</strong> a writing group showcase with the Station House Writers.<br />

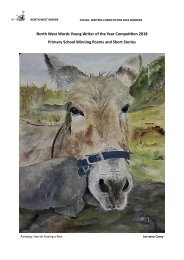

Images included in this issue are from Donegal natives, Lorraine Carey (a poet <strong>and</strong> an artist), <strong>and</strong><br />

Eamonn Bonner (a poet <strong>and</strong> photographer).<br />

When Emily Dickinson required a symbol for herself, she chose the wren, clover or spider. She was<br />

deeply familiar with the biology of such species. Much of her worldview was formed in her backyard<br />

garden. We are told that human beings are homophilous, that they tend to associate <strong>and</strong> bond with<br />

similar others. Homophily is posited over <strong>and</strong> over again in politics <strong>and</strong> religion <strong>and</strong> in much of our<br />

media as a type of justification for the impossibility of two diametrically opposed sides to ever come<br />

to a real <strong>and</strong> respectful underst<strong>and</strong>ing of each other. And then we have poets. And the best of our<br />

prose writers. Human beings who seem only too willing to enter into the reality of another, to<br />

embrace it, to become it, to write about it, <strong>and</strong> to offer it to the world at large as proof that we are<br />

amorphous beings, that we can <strong>and</strong> do walk in as many different forms as are extant on the world<br />

surface, <strong>and</strong> maybe even beyond that. The writers in this edition of North West Words Magazine all<br />

eschew homophily as a modus oper<strong>and</strong>i. Ali Znaidi's says 'No-one questions the seduction of<br />

corners' in “That Magic Within”. Attracta Fahy enters the throat of the thrush in “Philemos” <strong>and</strong><br />

Sharon Thompson's central character communes with the creatures in the shadows in her short<br />

story “The Healer”.<br />

Writers forage for those truths that hide behind the ostensible meaning of words. Language belongs<br />

to the people <strong>and</strong> with poems like “A Secret” by Michael, Kate Ennals' “What Word Would You<br />

Choose To Be?”, <strong>and</strong> Leo V<strong>and</strong>erpot's “Note Left On A Librarian's Desk”. Language belongs to the<br />

people <strong>and</strong> the writers in this section do just that.<br />

Much writing takes place after deep reflection. Paul Moore's short story “The Librarian” counters<br />

<strong>and</strong> subverts much of the homophily surrounding sectarian divide in the North. Just as importantly<br />

his main characters counter the populist protagonist <strong>and</strong> think just to think.<br />

4

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

“Hugh found it odd that when Bentham wasn't working out how to control people,<br />

he created the felicific (“happiness-making”) calculus. The calculus claimed to<br />

quantify the intensity, duration, likelihood <strong>and</strong> extent of pleasures <strong>and</strong> pains<br />

through an exponential equation.”<br />

We particularly love Beethoven's “Ode to Joy”. One of the mysteries of Art is paradox. Can joy<br />

spring from death? Does reading a poem in your native language bring peace even if you do not<br />

remember the meaning of the words? Can translations <strong>and</strong> free variations of poems dating back to<br />

844 reinvent those poems <strong>and</strong> reinvigorate them? The answer lies in the affirmative.<br />

Byron Beynon's “Roots”, Réaltán Ní Leannáin's “Áit”, Sean Golden's “Lel<strong>and</strong> at Cloonagh”, <strong>and</strong><br />

Miriam Nic Lochlainn's “Redemption” create a solidity by juxtaposing different keys <strong>and</strong> unexpected<br />

notes. Just like Beethoven. This edition sees the beginning of our Review Section.<br />

Kate Garrett's “You've never seen a doomsday like it” published by Indigo Dreams Publishing is<br />

reviewed by Deirdre Hines. The magazine closes with a selection of poems <strong>and</strong> one memoir piece<br />

from some of the members of Station House Writers. The eclectic form of Guy Stephenson's<br />

“Flicker” makes the reader pause <strong>and</strong> consider. Annemarie Gallagher's “What If Winter” redefines<br />

the tradition of fantastical, <strong>and</strong> Michael Forde's memoir piece “Cuban Crisis” is exemplary. His<br />

persona poem “I, Corrib” reinvigorates poetry of place. Joe Lynch's “ Avoiding Clichés” cleverly uses<br />

cliché to question <strong>and</strong> redefine cliché, bringing us back to where we started. Homophily <strong>and</strong> the<br />

power of good writing to counter all that is the worst in us.<br />

Enjoy.<br />

Nick Griffiths, Deirdre Hines <strong>and</strong> Deirdre McClay<br />

Copyright remains with the author, artist, photographer for all work in North West Words<br />

5

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Painting: Lucky Shell Beach, Ards Forest , Creeslough, Co. Donegal<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

6

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

North West Words <strong>and</strong> Donegal Creameries Poetry Competition 2017<br />

Winner: Noel Connor<br />

Judge: Kate Newmann<br />

Pictured left to right: shortlisted poets Eoin MacGuibhir, Stephanie Conn, Trish Bennett,<br />

David Gepp (accepting the Donegal Creameries Perpetual Trophy on behalf of Noel Connor),<br />

Breid Lindsay (Aurivo/Donegal Creameries) <strong>and</strong> James Finnegan.<br />

Competition judge, Kate Newmann<br />

1st prize winner: Noel Connor reading ‘ Damaged Tins’ at North West Words<br />

7

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Damaged Tins<br />

Twelve ninety-two forty-one<br />

my first recital at the Co-op till<br />

still trips off my tongue,<br />

a family mantra, unforgettable,<br />

twelve ninety-two forty-one,<br />

drummed into all of us by the front door<br />

<strong>and</strong> ‘don’t forget the divi’ we were told<br />

as we each became old enough, one by one<br />

to cross the busy road <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>le money.<br />

My mother had that shop terrorized,<br />

poor Mr Drain the manager<br />

would dread her coming in<br />

complaining about the wilted veg<br />

bruised apples or ‘yesterdays’ bread.<br />

Once she sent me back<br />

with a single damaged tin,<br />

‘we’ll all be poisoned by the lead leaking in’<br />

<strong>and</strong> I had to st<strong>and</strong> in front of him<br />

repeating word for word<br />

‘Mammy says …… ’<br />

8

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Those were the days<br />

long before the troubles on the road,<br />

armoured cars <strong>and</strong> army foot patrol<br />

the distant sound of city centre bombs,<br />

the never ending funerals<br />

filing past the silent shops.<br />

She died before the worst of it,<br />

before Black Friday or Bloody Sunday<br />

or the riots on Internment Day<br />

when the Co-op was wrecked in revenge,<br />

when I watched a hijacked truck<br />

shunt in reverse through the shop front,<br />

saw the crazy collapse of glass,<br />

the mangled racks <strong>and</strong> shelves<br />

<strong>and</strong> the kids scrambling in the tangle<br />

helping themselves to cigarettes <strong>and</strong> sweets.<br />

And under the big back wheels<br />

scattered all across the middle aisle<br />

a mess of flattened fruit <strong>and</strong> veg<br />

<strong>and</strong> all those crushed <strong>and</strong> damaged tins.<br />

Noel Connor<br />

9

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Galway Crystal<br />

You plied me with champagne in a crystal glass<br />

the light fizzed in its facets <strong>and</strong> danced a sparkling ring.<br />

“No daughter of mine’ll be on time, make him wait.” you said.<br />

The driver — your brother, slowed the car in agreement.<br />

When we arrived, the blessed virgin — mounted on granite<br />

stood guard, Celtic crosses scattered on the grave hill behind.<br />

A stream flowed under the stone-bridged road to the side<br />

feeding the lake in front, from where two swans watched<br />

as you held my h<strong>and</strong> to support my high, heeled step<br />

<strong>and</strong> carried the weight of my frock — the countryman’s Gok Wan.<br />

We strolled into that church built on immovable rock<br />

— a slope to its aisle.<br />

You slipped your arm in mine, laughed as you led me on<br />

me — with the autumn bouquet.<br />

Flower girls fizzed to grab hold of us both <strong>and</strong> towed us<br />

up that slope, to the altar.<br />

You sacrificed me there — to face the music<br />

half cut.<br />

Trish Bennett<br />

10

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Still Life in L<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

When all the colour has drained, unseen,<br />

from the large painting on the bedroom wall,<br />

that once was an exact replica of your life,<br />

with its hills <strong>and</strong> drumlins, half-hidden caves,<br />

gilt-edged sky; when the tracks <strong>and</strong> lanes laid down<br />

in charcoal have been erased to a grubby smudge<br />

<strong>and</strong> you can’t make sense of the emptied spaces,<br />

<strong>and</strong> you hate that hope is done with you too soon –<br />

a single word is enough to make the heart lift,<br />

to look doubt <strong>and</strong> madness in the eye <strong>and</strong> whisper,<br />

through gritted teeth, be gone! To those still sitting<br />

in the waiting room, this might be an unremarkable day<br />

<strong>and</strong> tomorrow may well smart <strong>and</strong> sting as you begin<br />

to pick the thorns from this unpronounceable name –<br />

today, this word’s a gift; your diagnosis rhymes with joy.<br />

Stephanie Conn<br />

11

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Euphemasia<br />

He spoke with grim aplomb<br />

A doyen of doctoral epithets<br />

It was an ‘adverse perinatal outcome’<br />

Commonly known as death<br />

The hospital was launching a review<br />

One of the internal kind<br />

The interviewer pressed for clarity<br />

A fog of nomenclature descended<br />

Procedural protocols would be parsed<br />

Pharmaceutical practices probed<br />

Obstetric choices examined along with<br />

Midwifery management patterns<br />

Seven fatalities over two years<br />

Rather a lot it would seem<br />

He struggled to appease the questioning zest<br />

Truth falls slowly, like feathers in a storm<br />

Administrative <strong>and</strong> clinical paradigms to be appraised<br />

Searching reviews <strong>and</strong> reports to be delivered<br />

Hypoxia, foetal cardiac distress <strong>and</strong> pre-eclampsia<br />

Deemed the suspects camouflaging the vagary<br />

The adverse perinatal outcome remains<br />

Patrick J. Cosgrove<br />

12

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Keeper<br />

The first one didn't care for words.<br />

The first one drank alone,<br />

gambling <strong>and</strong> grumbling.<br />

The first one knew I could never match<br />

his sadness.<br />

The first one seemed both safe <strong>and</strong> sorry,<br />

the first one took his salty grief<br />

<strong>and</strong> stepped soundly into my past.<br />

The new one says his life is a slow boil<br />

of aching days , like surly knots<br />

tied in a rope running through his fingers.<br />

He grips his spoon overh<strong>and</strong><br />

plunges it into the chilly pot,<br />

eating last night’s dinner for breakfast.<br />

He smirks then, claims his stomach<br />

is empty but his mouth is full.<br />

The new one covered his watch<br />

with his h<strong>and</strong><br />

when I asked the time,<br />

revealed it like a flipped coin<br />

when I guessed wrong.<br />

He wrote my name on the back<br />

of my photograph,<br />

pressed a fold into its centre<br />

stood it like an open book<br />

13

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

on the windowsill,<br />

it quietly keeled over<br />

by the time he was a week gone.<br />

Tonight I lowered<br />

a winebottle onto its side<br />

<strong>and</strong> slid it off the table,<br />

it went slowly<br />

like a ship sailing over the edge<br />

of a flat world.<br />

It waits unbroken on the heavy floor,<br />

minutes slip easily through the clock’s<br />

empty h<strong>and</strong>s,<br />

soft aches, sweet tears,<br />

no music to face.<br />

Gavan Duffy<br />

14

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Rivers of Sleep<br />

In her dream, she is unsure he is her husb<strong>and</strong>;<br />

the black-haired man in uniform<br />

looks like Tyrone Power<br />

—so long ago they danced together.<br />

Waking, she feels ashamed, yet knows how<br />

love can travel through the rivers of her sleep<br />

whispering what she cannot tell herself;<br />

that she forgets how fine he looked<br />

when they were stepping out, debonair<br />

in dinner-jacket, wide, fine-lipped mouth,<br />

now sees him propped up in a nursing-home,<br />

eyes alarmed, unable to speak,<br />

visits day <strong>and</strong> night with dinner mashed<br />

still warm from home, <strong>and</strong> bravest smile,<br />

h<strong>and</strong>s him pad <strong>and</strong> pen, at his comm<strong>and</strong>,<br />

to write again his wish to die.<br />

Frank Farrelly<br />

15

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

I was in Lanesborough today<br />

up Delvin Park cul-de-sac last pebble-dashed semi<br />

on the left beside the big field with pitch <strong>and</strong> putt<br />

<strong>and</strong> tennis courts <strong>and</strong> children’s playground I am<br />

studying mathematics or geography in an upper bedroom<br />

or I’m in some daydream state of waiting my father drives<br />

up in his long Ford car with lots of electricals in the back<br />

gets out walks along the driveway in his new tweed suit<br />

tailored by the local tailor with hidden legs my father tall<br />

with straight back big chest my heart lifts in welcome<br />

I was always glad to see him arrive home unless I was in<br />

a recent bit of bother all he might say after his Hello <strong>and</strong><br />

sharing the latest ESB joke might be I was in Lanesborough today<br />

it was his way of telling us he had travelled a fair distance that day<br />

even when I was older he would lay his h<strong>and</strong> on my forehead<br />

no words a Connemara man wishing me a silent good night<br />

James Finnegan<br />

Photo: Passing Rutl<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

16

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Way to Engl<strong>and</strong><br />

I shuffle in the stretch of the geansai you knit me, sister;<br />

wonder how you’ll like the bedroom all to yourself, brother;<br />

eat the last of your s<strong>and</strong>wiches, Mother;<br />

think over all your do’s <strong>and</strong> don’ts, Father<br />

<strong>and</strong> how I will really get on with Aunty Joan in London.<br />

I light a smoke at the bar; no smoking ban here yet,<br />

no need to hide my habit<br />

till I’m home again, I suppose.<br />

There’ll be no need to hide my bit of gayness either,<br />

except from Aunty Joan <strong>and</strong> her factory-husb<strong>and</strong>,<br />

till I’m home again, I suppose.<br />

A man from Woolwich starts to talk,<br />

he runs a museum of old cars <strong>and</strong> stuff,<br />

gives me a card to visit if I’m in the area.<br />

I hope Customs won’t find the magazines<br />

with pictures of naked girls, harmless stuff (no bondage),<br />

I could hardly have let them behind for mother to find.<br />

Over <strong>and</strong> over again, I check the bit of paper<br />

with the name of the man who’s giving me the job,<br />

his phone number <strong>and</strong> my PRSI number from Irel<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Noel King<br />

Geansai: jumper/sweater<br />

17

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Séan Dáiliocht<br />

Limpet, Bairneach<br />

Holding fast<br />

Dooey’s black rock harvest<br />

No duileasc here but dúlaman<br />

Periwinkles called wilks<br />

Hiding behind gelatinous fronds<br />

Picked <strong>and</strong> bucketed<br />

Boiled<br />

Drawn out with sewing needles<br />

Tasting of the sea<br />

The Bairneachs sizzling on the<br />

Hot range top<br />

The foot chewy, delicious<br />

A taste acquired<br />

From my mother<br />

With the skill<br />

Of stone striking shell<br />

Neolithic, in its simple beauty<br />

The burning of fires<br />

The sea birds calls, the same<br />

And each unanswered wave.<br />

Eoin Mac Guibhir<br />

18

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Dead Dog<br />

In a unit for the mentally infirm<br />

I offer you my love in the form of a dog<br />

so lifelike you expect its tail to wag<br />

or its soft muzzle to crinkle into smiles.<br />

It’s a collie – a she, a Daisy-dog to give comfort<br />

when your night-walls are soughed by the demented<br />

<strong>and</strong> God has forgotten the numbered password at your door.<br />

I have seen the woman with her baby many times,<br />

its doll head bobbing on her ribs,<br />

the lullaby that sings upon her tongue<br />

a comfort only to the bogus child<br />

immured within those skinned <strong>and</strong> skinny limbs.<br />

She walks the ward oblivious to all but<br />

what contentment comes before<br />

the longer shreds of darkness that will<br />

swallow up her memory whole.<br />

So I tender you my good intent –<br />

this spurious gift I think will link an alien present<br />

with the familiar past but even then,<br />

with all that has been lost to you,<br />

you recognise its falsity.<br />

‘That’s a dead dog,’ you say,<br />

the words raged from that part of you<br />

still holding on <strong>and</strong> holding on.<br />

Lynda Tavakoli<br />

19

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Painting: Solitude on Downhill Str<strong>and</strong>, Co.Derry<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

20

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

North West Words <strong>and</strong> Ealáin na Gaeltachta<br />

Irish Language Poetry Competition 2017<br />

Winner: Art Ó Súilleabháin Judge: Proinsias Mac a’Bhaird<br />

Pictured left to right: Proinsias Mac a’Bhaird (competition judge), Art Ó Súilleabháin (1st prize<br />

winner), Breid Lindsay (Aurivo/Donegal Creameries), <strong>and</strong> Michael Mac Aoidh (Ealáin na Gaeltachta).<br />

21

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Gur fút is breá liom<br />

1.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

do shíneadh ar tholg gorm<br />

do chorp scíthe go socair ag fanacht liom<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

2.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

meangadh ag briseadh ort<br />

do shúile oscailte i ngliondar áthais éigin<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

3.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

do bheag chaint ag sioscadh<br />

ag scaoileadh an tranglam i mo cheann<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

4.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

bheith ag liostáil gach dea-rud<br />

cuntas ar do ghaoine, do mhaoin álainn<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

5.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

an tríú uair a chur tú glaoch<br />

fós ag fiosrú mo chiall ‘s mo shláinte<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

6.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

am a chaitheann tú liom<br />

a shleamhnaíonn uainn i ngrá-chaint<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

7.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

do chiúnas in éineacht liom<br />

ag tóraíocht smaointe beaga fánacha<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

8.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

siúl ar thrá leat, lá gaofar<br />

gléasta don aimsir, clúdaithe ar a chéile<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

9.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

do theachta chuig mo chiúnas<br />

mar aingeal ag síneadh an tosta i mo threo<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

22

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

10.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

mo lámha i do ghruaig<br />

mo mhéara ag cíoradh na dlaoithe fionna<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

11.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

an póg ar chlár d’éadan<br />

cloch damhsa an locha ag socrú i do chroí<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

12.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

focail amhráin a chanann tú<br />

brí dhomsa amháin, ar do bheola gáireacha<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

13.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

meon na dearfachta ionatsa<br />

an inchinn lán le maitheas na gcleite bháin<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

14.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

lán mo bhos de chíoch<br />

ag ardú na dide le teann foinn ghnéis<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

15.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

bheith nocht sa leaba leat<br />

lom, craiceann le craiceann ag ardú fola<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

16.<br />

Is aoibhinn liom<br />

an mhaidin le cupán tae leat<br />

comhartha ar atá fós le teacht an lá sin<br />

tuigeann tú<br />

Art Ó Súilleabháin<br />

23

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

An Mhucais faoin Nollaig<br />

Tá giall an tsléibhe crua, glan, teann, gan comhréiteach<br />

Ina líne dhúshlánach rialóra de chuid Vere Foster :<br />

Cha dtig a dhreapadh a shamhlú, ach is gá a dhéanamh,<br />

Ar dhá chois nuair is féidir, ar cheithre ghéag nuair is gá,<br />

Umhal don tsleas, de shíor in éadan fána, bróga<br />

Ag polladh chraiceann sioctha an tsneachta, aer sna scamháin<br />

Ina chara a iarrann barraíocht, ina namhaid a ghearrann mion,<br />

Géilleann GoreTex an leathair, géilleann na matáin, na glúnta,<br />

Ach ní ghéilleann an dúnghaois sin atá gan duais, gan loighic:<br />

Tá súil le carn an mhullaigh agus deoir fán tsúil,<br />

An spéir faoina léine ghorm ag síneadh ó oileáin Alban<br />

Go srón Normannach Beinn Ghulbainn.<br />

Slogann gaoth is sliabh na focail a ghlaonn duine os ard le duine.<br />

Gréagóir Ó Dúill<br />

24

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

An Dá Thrá<br />

An slua ar fad<br />

ag déanamh ar an séipéal,<br />

is ag snámh in aghaidh<br />

easa a bhíos an mhaidin sin.<br />

Monabhar na bpaidreacha<br />

do mo leanúint,<br />

do mo tharraingt,<br />

do mo bhagairt<br />

is buillí rialta<br />

mo bhróga reatha<br />

ag tógaint<br />

diaidh ar ndiaidh mé,<br />

ar thóir na se<strong>and</strong>éithe.<br />

Talamh is spéir,<br />

uisce, crainn;<br />

bláthanna Lúnasa<br />

ag sileadh túise,<br />

an ghrian ag éirí<br />

thar Cheann Heilbhic,<br />

fáinleoga go meidhreach<br />

os mo chionn<br />

ag tumadh<br />

is ag gearradh spéire.<br />

An tAifreann thart<br />

sular shroicheas baile,<br />

bheartaíos freastal<br />

an lá dár gcionn,<br />

ag súil gur cuma le Dia,<br />

cuid mhaith,<br />

scéal an ghobadáin.<br />

Maire Ní Bhriain<br />

25

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Linntreoga Doimhne<br />

Ná tabhair aird ar bith ar na smaointe fánacha,<br />

gasta, guagacha, luathintinneacha<br />

A bhrúann iad féin chun tosaigh in gcuilithíní<br />

Ar imeall linntreog na smaointe<br />

Mar fhéileacáin phárlúis ag cóisir oíche<br />

Ach lean na sruthanna malla<br />

Go lár na linntreoige<br />

Agus tum go domhain<br />

Go grinneall fiú, agus fan.<br />

Fan agus bí foighdeach<br />

Bí foighdeach agus fan<br />

Lig do na sruthanna bogadh<br />

I measc na bpl<strong>and</strong>aí<br />

’S an duilliúr leathfhasta<br />

“S na nithe neamh-fhoirmthe<br />

Atá ag geimhriú sa bhfo-chomhfhios<br />

Agus le do chruthaitheacht<br />

Agus le do mhian ’s le do mheon ’s le do thoil<br />

Chomh luath ’s a fheictear nó a mhothaítear<br />

bachlóg nó eithne eolais<br />

Ag corraíl sa doimhneacht<br />

Gníomhaigh agus feidhmigh<br />

Feidhmigh agus gníomhaigh<br />

Tarraing, broid agus láimhsigh<br />

Ór-eithne an smaoinimh<br />

mar thaosrán<br />

26

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Taosrán na cruthaitheachta<br />

Go dtí go bhfuil sé ann.<br />

Ansin, cothaigh é,<br />

Neartaigh é,<br />

Séid air mar a dhéanfá le haibhleog<br />

Saoraigh smaoineamh an ghrinnill ó ghleothán an bhfo-chomhfhios<br />

Agus brúigh suas tríd na sruthanna malla<br />

’S na nithe neamh-fhoirmthe é,<br />

Thart ar na pl<strong>and</strong>aí ’s ar an duilliúr leathfhásta<br />

Déan neamart ar na féileacáin phárlúis sin de smaointe fánacha<br />

Go dtí go mbriseann sé tríd dromchla na réaltachta<br />

Isteach san anois.<br />

Seosaimhín Nic Rabhartaigh<br />

27

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Ar Bhruach<br />

Is tarraingteach an gorm os mo chomhair<br />

Ní fheicim ach é.<br />

Mé balbh, bodhar<br />

Blaisim an t-aer ar mo theanga.<br />

Is róchumhachtach an gorm os mo chomhair<br />

Bíogaim<br />

Cluinim mo chroí.<br />

I gcéin, tchím páiste<br />

Agus athair.<br />

Ní ligeann eagla, nó náire, domh bogadh.<br />

Is uilechumhachtach an gorm os mo chomhair<br />

Níl dadaigh ach é.<br />

Bogaim go mall, go heaglach,<br />

Ar crith.<br />

Le teacht i ngar di<br />

Aimsím crógacht,<br />

Léimim, amhail Fionn ina óige,<br />

thar h<strong>and</strong>brake, thar gearstick,<br />

Fáiscim í.<br />

Dubhán Ó Longáin<br />

28

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Painting: Sea Mist over Glashedy Rock, Ballyliffin Co.Donegal<br />

Lorraine Carey<br />

29

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Humber River Hospital<br />

at the time<br />

when I worked<br />

for Toronto's<br />

Humber River Hospital<br />

it was,<br />

they said,<br />

the most technologically advanced hospital<br />

in all the world<br />

outside of Dubai,<br />

with robots running on digital rails<br />

to deliver pills, blankets <strong>and</strong> syringes,<br />

messages<br />

<strong>and</strong> samples<br />

delivered by tube<br />

<strong>and</strong> a special system that could track the location<br />

of anyone in the building<br />

with gps,<br />

right down<br />

to the very portion<br />

of whatever room they were st<strong>and</strong>ing in.<br />

when I worked at<br />

Humber River Hospital<br />

we had:<br />

2 deaths of children caused by errors with the intercom,<br />

1 attempt by a guy in the ER to steal a gun from a policeman,<br />

1 woman collapsed in blood on the doorstep <strong>and</strong> forgotten for 30 minutes by the orderlies<br />

<strong>and</strong> 8 escapes from the insane ward on the fifth floor, of which<br />

3 ended in assaults<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2<br />

in attempted suicides.<br />

30

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

I used to walk there<br />

in the afternoon<br />

if I was going in for a night-shift<br />

<strong>and</strong> starting my day at 3 o'clock,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the sun overhead in summer<br />

would drain sweat<br />

until my mouth was dry<br />

<strong>and</strong> my shirt<br />

soaking. the hospital<br />

was located<br />

outside of the city<br />

<strong>and</strong> I lived<br />

in the middle of downtown<br />

but there were parts of the walk<br />

that were not unpleasant. one day in April<br />

I saw a hawk bring down a pigeon<br />

right into the roadway<br />

<strong>and</strong> cars swerved<br />

but nobody was killed<br />

as it stood on it's capture<br />

blinking<br />

with chicken-eyed stupidity.<br />

the control-room office I worked from<br />

was on the basement level<br />

right next to the main cafe<br />

<strong>and</strong> we spent a lot of time in there talking,<br />

drinking coffee<br />

<strong>and</strong> watching tv. it was in there that the intercom rang out from<br />

<strong>and</strong> I knew both the guys pretty well<br />

that had made the mistakes mentioned earlier. one of them was me.<br />

but we'd both worked there almost two years by then<br />

31

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

<strong>and</strong> anyone<br />

who works somewhere for that long<br />

in a mindless job where the biggest problem most days<br />

is resetting a robot that failed to detect a door<br />

can be forgiven<br />

for making one<br />

small mistake<br />

in an emergency,<br />

right?<br />

D.S. Maolalai<br />

Photo: High Flier - Seagull<br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

32

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

For Melissa, in another country<br />

I only ever saw you<br />

in summertime<br />

when it doesn't take much<br />

to look good.<br />

<strong>and</strong> yet<br />

I think in winter<br />

you would have been just as beautiful<br />

just as much a cat<br />

just as much a salad flower. your long<br />

polka-dot dresses, your sweet hair,<br />

your habit of working way<br />

beyond when anyone should be expected to work -<br />

you cured diseases<br />

constantly<br />

<strong>and</strong> love came from me<br />

constantly<br />

as I waited for you in bars,<br />

thinking but never telling you.<br />

sometimes I hear from you<br />

<strong>and</strong> decide<br />

I should say something<br />

but we are in different countries<br />

<strong>and</strong> love is not enough<br />

to bring anyone back.<br />

I know if someone prints this<br />

I'll show you<br />

<strong>and</strong> like a fool<br />

or a child with a picture<br />

<strong>and</strong> hope it matters<br />

but no,<br />

even poems don't mean anything<br />

anymore.<br />

D. S. Maolalai<br />

33

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Philemelos<br />

I hear the thrush every morning,<br />

high on her branch, she hides in ash,<br />

chirps between sycamore, <strong>and</strong> yew. Night<br />

waits quietly, a mother sings in dreams,<br />

her tufted belly plumage beating rhythm,<br />

chants the dawn moment.<br />

Morning moves its colour.<br />

She cackles, tones intact,<br />

sings to man <strong>and</strong> god.<br />

Since you left, yesterday befell years.<br />

Her dark bill leads your voice,<br />

flutelike in phases, po, po po.<br />

Rise in spirit song, gurgling, ee-o-lay.<br />

Her voice drifts light between echoes<br />

Upside down speckled heart,<br />

black shaped arrows pointing<br />

upwards, your fine thread, swift<br />

fingers crochet, ivory, pink, white.<br />

We rest in your minor keys, your melodic pause<br />

between notes, pulsating<br />

heartbeat. Mother, love is a birdsong.<br />

Attracta Fahy<br />

34

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Sudden Death<br />

I don’t know what I’d expected –<br />

that he’d be sitting upright <strong>and</strong> lazy-eyed,<br />

looking out the window<br />

at the front yard<br />

<strong>and</strong> the leaning pear tree?<br />

Or that he’d be lying, long-armed<br />

<strong>and</strong> long-legged on the couch,<br />

eyes only half-closed,<br />

<strong>and</strong> looking like he could get up anytime,<br />

if he really wanted?<br />

Instead they’d laid him<br />

in the cold, damp room they never used,<br />

his long, thin body<br />

stretched, uncovered,<br />

on the threadbare floor.<br />

My disbelief erupted in an unravelling flashback<br />

of what was being lost, was already lost,<br />

in this banishment,<br />

this nether world<br />

between being <strong>and</strong> unbeing.<br />

Teresa Godfrey<br />

35

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Metamorphosis<br />

Spinal spikes poke through my skin,<br />

overlap along my back<br />

My coccyx stretches,<br />

drops a scaly tail on the kitchen floor<br />

The fire starts behind my eyes<br />

Spews from nasal holes<br />

Heat melts reason<br />

Reptile in my brain controls<br />

My lungs’ pink spongy tissue,<br />

rises like yeast dough,<br />

pushes on my rib cage<br />

I hear my voice box grow<br />

A bellow surges in my belly<br />

Propels me up the stairs<br />

Crashing over discarded paint<br />

I holler out your names<br />

You take refuge in the hot press<br />

Text your dad from there<br />

Come home quick<br />

We’re an endangered species<br />

After the mop up<br />

my tail contracts<br />

lungs subside<br />

my eyes are back in sockets<br />

But below my spleen<br />

a squamate grows<br />

bang in the middle<br />

of my stomach<br />

With a flick of tail<br />

from time to time<br />

she churns a bloom<br />

of guilty chyme<br />

Bernie Crawford<br />

36

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

That Magic Within<br />

Suddenly the wind tosses a thin thread<br />

as the murmurs into the air are cast wholly:<br />

No one questions the seduction of corners.<br />

If there’s magic it is the seduction of seclusion:<br />

that is concealment.<br />

There are spiders, threads between corners<br />

<strong>and</strong> into corners, there is even the wall<br />

built upon secrecy.<br />

The bricks we never question or the muted tongues,<br />

or such postponed footsteps. How in the voice<br />

the murmur is enough!<br />

How in the rainbow<br />

the dream is enough!<br />

How is the sun adumbrated?<br />

How does the rainbow-painted cloud<br />

give mystery to the rays; that magic within?<br />

Ali Znaidi<br />

37

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

The Healer<br />

‘The bleeding has stopped?’ Mammy asks the woman in our kitchen.<br />

'Your own child put her h<strong>and</strong> on me there now, muttered the prayers in Irish <strong>and</strong> that was that.<br />

Your husb<strong>and</strong> saw it too. She's a healer all right, so she is.'<br />

I like the lady in the fur-collared coat. No-one other than Daddy thinks I'm much of anything. I'm<br />

supposed to look people in the eye <strong>and</strong> listen to their nonsense, but sure, all that just makes me<br />

tired.<br />

'Does the healing take it out of you, Molly?' the lady asks me in her nice accent. The bigness of her<br />

stops in the doorway that goes out into the unused front porch. 'You look exhausted now child. I<br />

cannot thank you enough. You'll have to take something for helping me?'<br />

'Are you sure it's stopped your bleeding?' Mammy asks taking a wad of notes from the lady with the<br />

hair curls. 'You didn't check? Are you sure now that it worked?'<br />

I steal a glance at the fancy lady who came in the huge car, as the squeal out of her is loud. 'Aren't<br />

you a woman yourself? There's no need to ask me those things with men present.’<br />

Daddy slicks a h<strong>and</strong> over his remaining hair, leans back on the stool by the open fire <strong>and</strong> puffs on his<br />

pipe. I know that's the way he is when he's pleased with me. After the woman leaves, <strong>and</strong> when<br />

Mammy isn't looking, he'll give me some sweets from the tin on the high mantlepiece, that his<br />

brother sent him from America.<br />

I don't notice the woman leaving as I'm away 'with the fairies' as Mammy calls it. There are no<br />

fairies like Mammy thinks. But, I suppose, I do go away into the shadows of my mind <strong>and</strong> the listen<br />

to the dark shapes that I can see out of the corner of my eyes.<br />

'I've told you time <strong>and</strong> time again, Nancy. Our Molly has the gift. And that educated woman left us a<br />

pile of money,' Daddy is filling his pipe with new tobacco <strong>and</strong> I'm sitting on the floor, pulling the<br />

stuffing from my doll's stomach <strong>and</strong> rolling it into little clumps. I feel it scratching against my cheek.<br />

'When God takes away something, he gives something else. They say as long as the child doesn't<br />

take any money herself, she'll keep the gifts she's been given. She could be one of the best healers<br />

around about here.'<br />

Mammy ties her dark curls back into the red ribbon she likes <strong>and</strong> slops in the basin on the table,<br />

washing the best cups the lady drank from. She says, ‘I'd far rather that she'd be like the other<br />

children.'<br />

'Even that doctor's wife came to get ‘The Healing’. You should be grateful to the Lord himself,<br />

Nancy. Our Molly is a h<strong>and</strong>some child with thick red hair as anyone would be proud of. You can't<br />

have it all. That doctor's wife there now said it herself; there's no point in us wanting her to be<br />

different. She’s the way she is <strong>and</strong> that’s it.’<br />

'It's the 1940s! We should be moving away from all the old codswallop of cures <strong>and</strong> magic. My sister<br />

says the priest will not like to hear of it at all. You know that Father Sorley is as mad as a bull, when<br />

he gets the notion.'<br />

'Molly needs to do this. Tis what they call her destiny.' Daddy puffs on rasping the dark stubble on<br />

his neck <strong>and</strong> I smell the socks he's rubbing together in front of the fire. 'She has to do it. Tis God's<br />

will.'<br />

38

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

'Once the bishop <strong>and</strong> the priests hear that she's performing miracles, you can explain it to them!'<br />

Mammy spits a bit when she's talking <strong>and</strong> her beautiful face scrunch up the words. She opens the<br />

back door <strong>and</strong> flings the water into the back yard scaring the two scrawny hens, who live despite<br />

the stone flags <strong>and</strong> tiny amount of grass.<br />

'Don't tell me that you're envious of your own eight year old daughter? Jealous of a child that isn't<br />

the full shillin'?' He's goading her so she'll not miss him when he's out in the pub later. 'She'll need<br />

something, as no man will take her on despite the pale skin <strong>and</strong> angelic face. She'll need to be able<br />

to fend for herself because she's got nothing between her pretty little ears.'<br />

Mammy wipes her eye with the back of her h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> sniffs a bit. I can tell then that in the silence,<br />

she's staring at me. They both are.<br />

'This next one better be all right?' Mammy mutters rubbing her big belly. 'Took long enough to get<br />

this far again. This next one better come out fine <strong>and</strong> talk to us properly. It better not be as odd as<br />

two left feet, like that yolk over there.' She's pointing at me.<br />

I know they've waited a long time on this baby to come into Mammy. She used to say, 'Tis his fault.<br />

That thing between his legs ain't good for nothing. He's not someone I should've married. My own<br />

were in a hurry to be rid of the eldest, with another five daughters to sort out. I married beneath<br />

myself <strong>and</strong> I'm paying the price now.'<br />

That's why, Daddy asked me to rub his bits for him. They both wanted a normal boy <strong>and</strong> he asked<br />

me to heal between his legs. It all seemed to work fine. He liked me to do it for him <strong>and</strong> sure I<br />

couldn't say no to Daddy. It's our secret though, as it would make Mammy even more cross than<br />

she is already. Even I know that if she heard I healed Daddy's private place, she'd be livid. Daddy<br />

said his bother Vincent needed 'the healing' on his mickey too. I know he's not married, so I would<br />

only do it the once for him <strong>and</strong> he got angry.<br />

'Thems for babies,' I told him as I heard the birthing woman talking to Mammy near the butcher's<br />

about making sure Daddy didn't wear his trousers too tight, or sit too long in the hot baths. 'You<br />

don't need the babies yet,' I whispered at Uncle Vincent, 'you don't need the healing.'<br />

He got wild angry when his mickey didn't work near me after that. I'm glad though he's off in America<br />

now, as I don't like the air about him at all. Healing Daddy is different. I'm of his blood <strong>and</strong> his<br />

'favourite girl'. I like it when he whispers how I helped him have another pretty Molly in Mammy's<br />

tummy. Even I know that the air about Daddy can be wrong sometimes.<br />

'It's a gift you have,' Daddy's blue eyes are proud. 'Make me better, Molly.'<br />

He is better since the baby is coming. Mammy's happier too, apart from when she is with me of<br />

course.<br />

'I can taste the hate,' I tell Daddy when Mammy's puts on her good scarf <strong>and</strong> scuttles off to the bus<br />

to go to her nearest sister's. 'It comes out of her. I can even taste the hate off her.'<br />

'She doesn't hate you,' Daddy tells me. I can always tell when people are telling me wrong things.<br />

Out of the corner of my eyes I can see the darkness around their heads.<br />

'Do you see angels?' Daddy asked me last year when I was doing the healing on his mickey.<br />

39

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Someone told him that the best healers could see angels. I know the nuns think that angels have<br />

wings <strong>and</strong> halos <strong>and</strong> sit in clouds or on our shoulders. They believe it, God love’em. But it's not<br />

right. I tried to tell them they were wrong about the angels, but they just took to beating me. So, I<br />

gave up.<br />

People do have a sort of halo but there's no angels on their shoulders - there's just air. Maybe it's<br />

the angels breathing that I can see, but I call it good <strong>and</strong> bad air. People breathe it, surround themselves<br />

in it <strong>and</strong> smell of it.<br />

I always look around people <strong>and</strong> I find out how their air feels. That tells me all I need to know <strong>and</strong><br />

sometimes the shapes in the shadows tell me things too. They don't use words nor nothing. It's<br />

hard for me to explain, <strong>and</strong> I know from the thumping Mammy did on me when I tried to make<br />

sense of it, that it is better now just to let it be <strong>and</strong> not think or talk on it too much.<br />

It's best, for a lass like me, not to talk much at all – about anything.<br />

'I see air, Daddy,' I told the only person who listens. 'But now that Mammy has a baby in her, you<br />

won't need The Healing anymore. I'll just heal your air by saying my prayers. I don't need to go near<br />

you mickey again. I'll sing to the air around ya, <strong>and</strong> make you better.'<br />

'I'm a bad man,' he muttered.<br />

'I know Daddy....' I breathed on him <strong>and</strong> kissed his cheek.<br />

'Heal me, Molly. Make me better inside.'<br />

He was pale then, even Mammy said it. For days he was white as the sheets she made me fold with<br />

her. I know sometimes Daddy's air still goes bad but I hold his arm <strong>and</strong> breathe into his pipe <strong>and</strong><br />

turn him good again. Mammy's air is always tight though. I don't seem to be able to cure her from<br />

anything, or make her love me at all. The creatures in the shadows tell me to leave her be. I try not<br />

to care about her insides or the heart of her.<br />

I know babies bring beauty into the world. All the women say it outside Mass when they touch<br />

Mammy's belly for luck.<br />

The thoughts of the baby makes me happy inside too. The shadows have told me there's good<br />

things to come for me. They say that I, Molly McCarthy, will have better times.... maybe the baby<br />

will bring those good things with him?<br />

Sharon Thompson<br />

40

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

A Secret<br />

His stale breath. His hollow eyes. He tries to take me into his guise.<br />

His promises of love wrapped in warped charm, a damaged boy he intends to harm.<br />

A pious exterior of wit <strong>and</strong> grace, his sign of peace steeped in disgrace; shame on those<br />

who allowed him save face.<br />

Michael<br />

Photo: Bronze Statue Hiring Fair Boy, Market Square, Letterkenny<br />

Eamonn Bonner<br />

41

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

The visit<br />

we’ll play tea parties today<br />

my mother seems to say<br />

she h<strong>and</strong>s something over<br />

to me <strong>and</strong> smiles she nods sagely<br />

I agree this is a pretty party<br />

then she tries to kick her<br />

feet chair bound<br />

she nonetheless exudes a certain<br />

energy I look closely at her face<br />

still a rose on her cheek <strong>and</strong> her grey<br />

hair sets it off<br />

so much like the imaginary<br />

fine porcelain she h<strong>and</strong>ed me<br />

then time to say goodbye<br />

my brother so like a minister<br />

as he presses her arm meaningfully<br />

leans down to reassure<br />

part of the pleasure of meeting<br />

is the saying goodbye<br />

Anne McCrea<br />

42

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

What Word Would You Choose to Be?<br />

I’d want a word with body, cute with curlicues<br />

A dainty word that alerts, to inveigle you …<br />

in close. I’d like a whisper of intrigue, like why, maybe?<br />

Or I could be a cry, a call of nature, forged<br />

A word that stutters life, a craw in the back of your throat<br />

Or the meaningful bleat of a new born kitten<br />

Trapped in a sack of stones<br />

I’d like to sound like a badge of courage – suffragette, for instance<br />

Or be The Scream. Yes, I’d want to be a shout for change<br />

But, also a word that makes you laugh<br />

And signals cunning. I’d be a clever word, packed with guile<br />

A flash of solar, a ray of lunar, scarlet with a green feather boa<br />

Word of significance. Burlesque? Like a Reubens woman.<br />

There, I have it. If I could choose to be one word?<br />

Word I’d choose is ‘flesh.’<br />

Kate Ennals<br />

Note Left on a Librarian’s Desk<br />

In the midst of a time<br />

when values are shed<br />

like house-animal-d<strong>and</strong>er,<br />

peace a perfect suspect,<br />

war always in bed, a<br />

potent rascal on call,<br />

constant opinions on screens<br />

with dumb mouths<br />

unable to pause for fear<br />

silence will crack<br />

the space between vows<br />

of reason <strong>and</strong> rhyme,<br />

now's the time to step up<br />

<strong>and</strong> shout<br />

the ultimate outrage:<br />

"Someone has torn eight<br />

pages out of The<br />

New York Review of Books."<br />

Leo V<strong>and</strong>erpot<br />

43

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Timing<br />

You were part of my plan<br />

but you arrived too early<br />

I had a decade of loves<br />

<strong>and</strong> losses<br />

<strong>and</strong> romantic encounters<br />

mapped out in my head.<br />

Ours was a long distance affair<br />

in that sweltering summer of ‘95,<br />

that surprised us both with its intensity.<br />

Despite my intentions,<br />

I lay bare my vulnerabilities<br />

And your response was to wrap me<br />

even tighter in your tender embrace,<br />

<strong>and</strong> assure me that<br />

of course,<br />

I was worthy of love.<br />

I responded with tears<br />

when you told me I was beautiful<br />

Years of self-criticism had taken its toll.<br />

I thank the gods that you came when you did<br />

my miniscule store of confidence<br />

could not have taken many blows.<br />

Your every kiss reassured me<br />

I’m here,<br />

I’ve got you,<br />

I’m going nowhere.<br />

Your timing was perfect.<br />

Jackie Lynam<br />

44

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

The Librarian<br />

As a librarian, Hugh always felt he was privileged to have knowledge at his fingertips. He could order<br />

books from around the globe, check their progress as they flew <strong>and</strong> sailed toward him <strong>and</strong> then<br />

welcome each into his world. He was a quiet man, a studious worker who the staff <strong>and</strong> students of<br />

the university knew little about. He had perfected the art of remaining inconspicuous, avoiding the<br />

clatter of the refectory, talking little <strong>and</strong> focussing on his daily tasks in his specialty area of sociology.<br />

Hugh regarded Durkheim, Weber, Mauss <strong>and</strong> Marx as colleagues, if not friends. Now the bright<br />

eyes in his gaunt face checked the books once more <strong>and</strong> looked toward the dial of the wall clock. Its<br />

thin h<strong>and</strong>s read six thirty three. Time enough for Hugh to walk across Derry <strong>and</strong> the River Foyle to<br />

the Waterside train station.<br />

During term, Hugh occasionally returned to his native Belfast on weekends; however this weekend<br />

was for Mary. He would disembark his train at Coleraine <strong>and</strong> then catch the bus to the seaside town<br />

of Portrush <strong>and</strong> the faded gr<strong>and</strong>eur of the Victorian guesthouse he visited at least a couple of times<br />

each winter.<br />

Students largely ignored this anachronism as he slowly walked along the Northl<strong>and</strong> road. His old<br />

grey overcoat with its green satin inner, his pleat trousers <strong>and</strong> olive green tie suggested to them he<br />

was a remnant. Some looked up from mobile phones <strong>and</strong> smirked; some felt a sort of sorrow <strong>and</strong><br />

Hugh nodded <strong>and</strong> moved along. From Northl<strong>and</strong> he turned into Asylum Road. He looked at the<br />

mossy rock of the wall that bordered the left h<strong>and</strong> side of the street all the way to The Str<strong>and</strong><br />

below. Behind this buckled rock the first asylum in the county of Derry, indeed one of the first in<br />

Irel<strong>and</strong>, was built in the 1826. Hugh often imagined he could still hear the inmates. A second asylum<br />

was built near the Falls Road in Belfast during the same year supporting the thesis that lunacy <strong>and</strong> a<br />

state based on sectarianism may indeed be interrelated. Hugh chuckled at the thought <strong>and</strong> recalled<br />

ten years earlier, in 1816, William Todd, as the Secretary of the Asylum Commission, had commented:<br />

“Lunatics abound more in Ulster than any other part of Irel<strong>and</strong>”. Hugh had lived to see it proven.<br />

The abounding lunatics, Hugh reasoned, were more obvious in Ulster because the Provence was<br />

impoverished <strong>and</strong> the insane poor are more conspicuous than the eccentric rich. A wealthy idiot,<br />

Hugh had read, could be tidied away as a ‘single lunatic’ by family <strong>and</strong> friends, as had been members<br />

of the British Royal Family in 1788, 1801, 1811 <strong>and</strong> 1916. Hugh loved these odd facts <strong>and</strong><br />

history almost as much as sociology. He loved how as time recedes the vast inequalities <strong>and</strong> secrets<br />

of the world become visible. He feared how power in the present obscures the very same.<br />

45

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

If pressed, Hugh could have explained how the asylum was designed along the lines of Jeremy<br />

Bentham’s Panopticon, a template used for many state buildings including goals, schools, hospitals<br />

<strong>and</strong> universities. Any place, in fact, in which a supervisor seeks to keep an eye on many people at<br />

once. The basic architecture consisted of a semi circle, or circle, the centre of which served as an<br />

observatory. Inmates, students <strong>and</strong> patients could be held in rooms along thin corridors reaching<br />

out from the superintendent’s central vantage point. While a superintendent could not watch every<br />

one all of the time, he or she was granted an overview of every cell within the structure. Hence the<br />

occupants never knew when they were being observed. This would supposedly persuade them to<br />

behave for fear of being spied upon. Hugh also understood that the asylum had long been replaced<br />

by more modern regulatory arms of the state including a technical college, the unemployment<br />

exchange <strong>and</strong> the police station, all with new eyes in the form of dozens of CCTV cameras hanging<br />

at all angles from buildings <strong>and</strong> lamp posts. As he passed their prying gaze, Hugh appeared wholly<br />

inconspicuous. Both on <strong>and</strong> off line, the state found the librarian unremarkable.<br />

Hugh found it odd that when Bentham wasn’t working out how to control people, he created the<br />

felicific ("happiness-making") calculus. This interested Hugh more, although he questioned<br />

Bentham’s faith in the empirical. The calculus claimed to quantify the intensity, duration, likelihood<br />

<strong>and</strong> extent of pleasures <strong>and</strong> pains through an exponential equation. The tidy dream of a reductionist.<br />

Hugh threw this thought aside as he turned right onto Princes Street. The light here was more<br />

optimistic <strong>and</strong> the road led to a better life in the opulent <strong>and</strong> wider Clarendon. Here the terraces<br />

were Georgian, chipped red brick, arched doors <strong>and</strong> French windows. The uneven pains of glass in<br />

these appeared like dark watery pools <strong>and</strong> contained bubbles of air trapped for over two hundred<br />

years. In spring, planter boxes burst with bright flowers scenting the charmed lives of professionals;<br />

lawyers, accountants, designers <strong>and</strong> dentists. Masterful women <strong>and</strong> men whose position <strong>and</strong><br />

income rendered them immune to surveillance <strong>and</strong> madness.<br />

Hugh stepped quickly past the dead slab of architecture that was Tesco’s on the Str<strong>and</strong> Road <strong>and</strong><br />

toward <strong>and</strong> across the River Foyle via the newly erected Peace Bridge. In the station, his train was<br />

waiting. He read while travelling allowing the journey to relax <strong>and</strong> lead him from train to bus, <strong>and</strong><br />

then to the almost deserted seaside town. Built in Victorian times, Portrush was slowly being eaten<br />

away by the wind <strong>and</strong> waves. Arriving at the guesthouse he was shown to his room. It was the same<br />

room he had known over the years with its high walls, floral carpet <strong>and</strong> bay windows. It was<br />

magnificently fitted with an assortment of antique furniture that had been gathered from the once<br />

far reaches of the British Empire. There were Oriental cushions, a rounded brass table from India<br />

into which was etched a beautiful ink blue peacock, an umbrella <strong>and</strong> hat st<strong>and</strong>. The windows were<br />

bordered by plush curtains <strong>and</strong> foreign l<strong>and</strong>scapes hung about the walls. A Turkish divan sat close<br />

46

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

by the fireplace <strong>and</strong> beside a huge bed a shaded lamp threw shadows. Hugh opened his case <strong>and</strong><br />

from an ornate box within produced a set of small silver trays <strong>and</strong> a pipe richly ornamented. He<br />

waited now for a faint knock at the door <strong>and</strong> felt his heart jump a little when it arrived. He moved<br />

across the room <strong>and</strong>, opening the door, stood facing Mary. Their eyes reached into each other <strong>and</strong><br />

after a still moment they exchanged a gentle kiss. Hugh then led his companion into their<br />

cl<strong>and</strong>estine world <strong>and</strong> Mary placed her small travel case on the huge bed.<br />

The pair had met during the 1960s during the first civil rights demonstrations held in Belfast <strong>and</strong><br />

Derry. Mary was from Dublin <strong>and</strong> studying botany, Hugh had just finished his arts degree <strong>and</strong> a major<br />

in History. Anything seemed possible at this time; the sky like a window. Even a romance<br />

between a lapsed Protestant <strong>and</strong> a radical Catholic seemed somehow perfect <strong>and</strong> blessed. Mary<br />

<strong>and</strong> Hugh fell deeply, but as B Specials dispersed the marches, <strong>and</strong> later, as the Vietnam War<br />

offered up the bodies of children <strong>and</strong> the old on television nightly, they grew to underst<strong>and</strong> that<br />

this love required protection. They retreated into solitary public worlds, Hugh a bachelor <strong>and</strong><br />

librarian, Mary a spinster <strong>and</strong> botanist. Over time, relatives <strong>and</strong> friends ceased enquiring about<br />

romance, ideas of marriage <strong>and</strong> children. To the outside world, Hugh <strong>and</strong> Mary appeared isolated<br />

<strong>and</strong> reserved; a little shy, <strong>and</strong> almost certainly frigid.<br />

Now, as they often did, they would spend their first evening reading together from essays <strong>and</strong> stories<br />

that had come to their attention in the months apart. They chewed over world events <strong>and</strong><br />

surprised each other with new ideas <strong>and</strong> fictions. Their reading was broad <strong>and</strong> adventurous. They<br />

loved the careful <strong>and</strong> the considered as much as the experimental <strong>and</strong> the fresh. They listened to<br />

music <strong>and</strong> drank red wine late into the evening as the coals flickered blue <strong>and</strong> orange. Then they<br />

would sleep together, holding each other close <strong>and</strong> listening as the cold North Atlantic surged <strong>and</strong><br />

gusts of wind caused the window pains to groan.<br />

On Saturday mornings the pair walked on the deserted beach, along the promenade, listening to<br />

the green grey sea. They sometimes would fill with bliss <strong>and</strong> they knew they were among the<br />

happiest of couples that had ever lived.<br />

In the evening they often followed a ritual begun years before. They filled Hugh’s Chinese pipe with<br />

golden brown sap from poppies Mary grew in her greenhouse. She had smuggled seeds into Irel<strong>and</strong><br />

from a botanic garden in London. They laughed like children as the blue smoke rose in thick wisps<br />

<strong>and</strong> the opium’s warm embrace overcame them. They had never given up on the idea that such<br />

pleasure could be a delight on occasion rather than an addiction. It was, to the pair, a way of banishing<br />

an increasingly invasive state from their bodies <strong>and</strong> minds, a means of opposing in a very real<br />

sense what vigilantes, the church <strong>and</strong> the philistines in government wanted to impose through<br />

ignorance <strong>and</strong> fear.<br />

47

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Finally, they would spend the Sunday afternoon writing. They worked carefully in order to leave the<br />

world <strong>and</strong> each other a diary. Both wrote simultaneously such that on parting each retained a copy<br />

in the others h<strong>and</strong>. Some day, both Mary <strong>and</strong> Hugh understood, one would return to this room<br />

alone to mourn the other, stolen through age, death or dementia. This diary recounted the<br />

w<strong>and</strong>erings of their imaginations, their meetings, their thoughts <strong>and</strong> the joys they had found. It<br />

would remain <strong>and</strong> would comfort the one left behind. This was their life insurance. Eventually<br />

who ever outlived the other would place this book in the shelves of the University library. Hugh had<br />

already created its ISBN, reference <strong>and</strong> title. They agreed to name the book ‘Joy’, <strong>and</strong> to list the authors<br />

as unknown. This book would remain deliberately off the syllabus. They would position it<br />

among anthropological studies made during the mid to late nineteenth century in a patch of<br />

peace that sat between the Crimean <strong>and</strong> World War One.<br />

Hugh looked now to Mary, he loved her in every sense. Outside the world was a bitter cold while<br />

here in their cocoon the pair managed to shelter in their own republic. Mary gazed back <strong>and</strong> they<br />

both laughed knowing their bodies had grown old, their clothing was well dated, but their minds,<br />

when they met, where spring. Hugh held Mary <strong>and</strong> kissed the top of her tiny head, her widow’s<br />

bun grey <strong>and</strong> tight. They then made love so softly that angels may have appeared.<br />

And from this place, early on a Monday morning, they each returned to their lives, so unremarkable<br />

they became invisible. As Hugh boarded the train back to Derry he looked at the rounded casing<br />

of the security camera that announced surveillance <strong>and</strong> simultaneously obscured the cameras aim.<br />

He laughed <strong>and</strong> he wondered why Bentham had left us this offspring of the Panopticon instead of<br />

his happiness principle. He checked his own happiness calculus <strong>and</strong> found it to be overflowing <strong>and</strong><br />

he reminded himself to look at Spinoza again. Spinoza, Mary would love that.<br />

Paul Moore<br />

48

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Reflection on Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Self-Portrait<br />

If we were frightened<br />

we hid it well;<br />

ratcheting out of control<br />

just enough <strong>and</strong> no more.<br />

The drunk, the boor,<br />

the perfect charmer.<br />

We played them all<br />

right up to the hilt.<br />

You welcomed the lash,<br />

the fist, the yielding.<br />

Submitting to death,<br />

rebirth, death again.<br />

And I, in my wild<br />

<strong>and</strong> headstrong way,<br />

sought my own oblivions<br />

to shield my young <strong>and</strong> fragile heart.<br />

Now, in the overlap<br />

of our reflections,<br />

we come face-to face<br />

<strong>and</strong> gaze at each other’s tender beauty.<br />

Teresa Godfrey<br />

49

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Roots<br />

Hearing my mother speak Welsh<br />

I am at one<br />

with her voice,<br />

that sense of place<br />

where her tongue<br />

rests <strong>and</strong> feels at home.<br />

I know the language<br />

breathing inside<br />

imagination's flame.<br />

Vowels across time,<br />

a craft to decipher<br />

like a scent which bloomed.<br />

I witness her happiness<br />

that only the words can bring,<br />

those natural roots which grow within.<br />

Byron Beynon<br />

50

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Ait<br />

Dá mbínn i m’fhear<br />

chumfainn oidhreacht na gcianta,<br />

táin is tóraíocht is éachtaí móra.<br />

I mo shuí go socair ciúin gach tráthnóna,<br />

ag carnadh mo chuid focal, an ceann amháin ar bharr a chéile.<br />

I m’am saor.<br />

Ag deireadh lae.<br />

Sa chathaoir uilinn.<br />

Ach tá tachráin agam féin le beathú is le ní is le cur a luí.<br />

Tá bráillíní nite le filleadh, ‘s veisteanna ‘s stocaí, leis.<br />

Iad siúd uilig le carnadh i mullach a chéile sa phrios.<br />

Tá dorn amháin sa doirteal, dorn eile ag stiúradh obair bhaile.<br />

Éadaí salaithe á gcur sa mheaisín, urlár á scuabadh go híon.<br />

Lónta á réiteach don mhaidin lá ar na mhárach.<br />

Leaba.<br />

Suan.<br />

Beirt a chromann chun saothair gach oíche.<br />

Duine acu ina shuí ar a thóin.<br />

I ndiaidh a shuipéar a ithe.<br />

Sa chlapsholas.<br />

Leis féin.<br />

Réaltán Ní Leannáin<br />

51

NORTH WEST WORDS<br />

SPRING / SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> ISSUE 9<br />

Lel<strong>and</strong> at Cloonagh<br />

in memoriam Lel<strong>and</strong> Bardwell, 1922-2016<br />

I<br />

I live here now, like a goddess.<br />

Whins grow wherever they want.<br />

I hang my clothes on shrubs to dry,<br />

Drink wine in the open air.<br />

A stone ramp runs into the ocean.<br />

Clothes scatter over heaps of books.<br />

I float in the sea, recite poems to the moon.<br />

The wind will waft me back to the shore.<br />

––free variation on a poem by Yu Xuanji (844–868)<br />

Sky <strong>and</strong> cloud combine,<br />

Fog <strong>and</strong> sea are one.<br />

The Milky Way spins.<br />

A thous<strong>and</strong> sails cavort.<br />

Entranced, I hear the sky<br />

ask where I’m heading.<br />

A very long way, I say,<br />

far past the sunset.<br />

I write it out in a verse<br />

that bewilders even me.<br />

The kestrel surfs a gale<br />

that will carry me<br />

past Inishmurray to<br />

Tir na nÓg.<br />

II<br />

––free variation on a poem by Li Qingzhao (1084–1155)<br />

III<br />

Anyone can comply with a rhyme scheme<br />

but I can descrie traces of flowers<br />

in the dark of the moon<br />

or brambles dangling in the morning mist.<br />

Treasure is buried deep.<br />

I am old enough now to write as I will<br />

on any kind of note paper but<br />