9781622824588

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

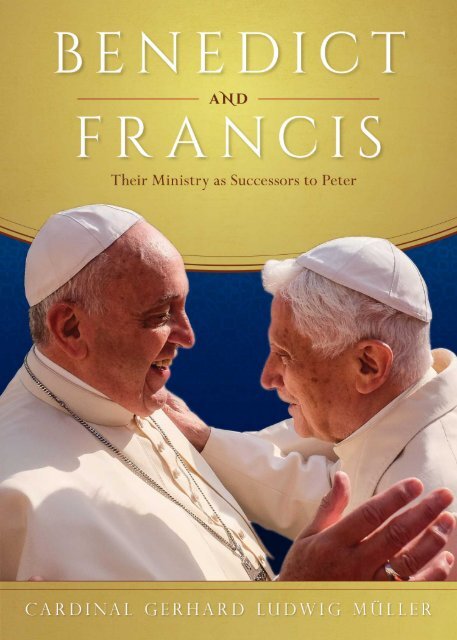

Benedict and Francis

Gerhard Cardinal Müller<br />

BENEDICT<br />

AND<br />

FRANCIS<br />

Their Ministry as Successors to Peter<br />

Translated by Michael J. Miller<br />

SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS<br />

Manchester, New Hampshire

Original German edition: Benedikt und Franziskus: Ihr Dienst in der Nachfolge<br />

Petri: Zehn Jahre Papst Benedikt, copyright © 2015 by Verlag Herder GmbH,<br />

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany.<br />

English translation copyright © 2017 by Michael J. Miller<br />

Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved.<br />

Cover design by Coronation Media.<br />

On the cover: Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis meet, September 28,<br />

2014, St. Peter’s Square (E818X9) © Realy Easy Star/Alamy Live News.<br />

Interior design by Perceptions Design Studio.<br />

Scripture quotations are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible — Second<br />

Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition), copyright © 2006 National Council<br />

of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission.<br />

All rights reserved worldwide.<br />

Citations from Heinrich Denziger, Enchiridion Symbolorum (cited as DH), are<br />

taken from the 43rd edition, edited by Peter Hünermann (San Franciso: Ignatius<br />

Press, 2012).<br />

Citations from Vatican II documents are taken from Austin P. Flannery, ed.,<br />

Documents of Vatican II (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1975).<br />

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted<br />

in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or<br />

otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a<br />

reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.<br />

Sophia Institute Press<br />

Box 5284, Manchester, NH 03108<br />

1-800-888-9344<br />

www.SophiaInstitute.com<br />

Sophia Institute Press ® is a registered trademark of Sophia Institute.<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Names: Müller, Gerhard Ludwig, author.<br />

Title: Benedict and Francis : their ministry as successors to Peter / Gerhard<br />

Cardinal Müller; translated by Michael J. Miller.<br />

Other titles: Benedikt und Franziskus. English<br />

Description: Manchester, New Hampshire : Sophia Institute Press, 2017. |<br />

Includes bibliographical references. | Petrine office<br />

Identifiers: LCCN 2017012271 | ISBN <strong>9781622824588</strong> (pbk. : alk. paper)<br />

Subjects: LCSH: Popes — Primacy. | Apostolic succession. | Benedict XVI, Pope,<br />

1927- | Francis, Pope, 1936- | Catholic Church — Doctrines.<br />

Classification: LCC BX1805 .M8513 2017 | DDC 262/.13 — dc23<br />

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017012271<br />

First printing

Contents<br />

The Primacy of Peter in the<br />

Pontificate of Benedict XVI . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

Truth and Freedom: What Does<br />

Laicity Mean for Christians? . . . . . . . . . . . 31<br />

Poverty as a Way of Evangelization:<br />

Reflections in the Spirit of Pope Francis . . . . . 63<br />

Theological Criteria for Ecclesial<br />

and Curial Reform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93<br />

Tenth Anniversary of Pope Benedict. . . . . . . 109<br />

v

Benedict and Francis

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

The Primacy of Peter<br />

in the Pontificate<br />

of Benedict XVI<br />

Rome, Campo Santo, April 17, 2015<br />

3

On April 19, 2005, the Catholic world heard the<br />

unforgettable words from the Loggia [balcony]<br />

of Saint Peter’s Basilica: “Annuntio vobis gaudium<br />

magnum. Habemus Papam: Eminentissimum ac<br />

Reverendissimum Dominum Josephum Sanctae Romanae<br />

Ecclesiae Cardinalem Ratzinger.” The pontificate<br />

of Benedict XVI lasted almost eight years, until<br />

February 28, 2013.<br />

This is not the occasion to evaluate the place of<br />

this pontificate in Church history or to get involved<br />

in controversies that arise in evaluating any historical<br />

personage. Rather, it is a matter of asking theologically<br />

how our faith in Jesus Christ was promoted<br />

by Pope Benedict and how we were led to a deeper<br />

understanding of the whole mystery of salvation: the<br />

revelation of the Triune God and consequently of the<br />

Church’s mission in our time.<br />

5

Benedict and Francis<br />

Peter as the visible principle of unity<br />

The popes, as successors of Peter, are the visible head<br />

of the pilgrim Church, and as pastors and teachers of<br />

the Universal Church they are vicars of Jesus Christ,<br />

who, on account of the Incarnation, is inseparable<br />

from the Church, His Body.<br />

The cardinals are not the ones who confer authority<br />

to the newly elected pastor of the Universal<br />

Church. Therefore, neither does the Pope exercise<br />

his authority in the name of the Church, or of the<br />

College of Bishops, which he heads, or of the Roman<br />

Church, which, by means of the College of Cardinals<br />

and the dicasteries of the Roman Curia, shares<br />

responsibility for the Pope’s duties with regard to the<br />

Universal Church. The Pope answers to Jesus Christ<br />

alone and is supported in his universal ministry by<br />

the Church of Rome. Jesus Christ, the Lord and Head<br />

of His Church, is the sovereign; from Him proceeds<br />

all spiritual authority to govern, teach, and sanctify<br />

the people of God in the power of the Holy Spirit<br />

(cf. Lumen Gentium [LG] 20). The deliberations of<br />

the cardinals in the preconclave, along with their<br />

search for a suitable candidate and a coalition of votes<br />

6

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

forming a moral majority of more than two-thirds<br />

in the conclave, are only a prayer to God: “Show us<br />

whom you have chosen” (cf. Acts 1:24).<br />

Jesus Christ, the true Head of the Church, bestows<br />

on the Bishop of Rome, as the successor of the<br />

apostle Peter, the fullness of authority to represent<br />

Him visibly as the universal teacher and pastor in the<br />

pilgrim Church on earth. The sacred primacy belonging<br />

to the Bishop of Rome, with its infallible teaching<br />

authority, is nothing less than the actualization of<br />

the perpetual and visible principle and foundation<br />

of the unity of faith and the communion that Christ<br />

Himself instituted forever in the Church in the person<br />

of Saint Peter (cf. LG 18). The primacy of the<br />

Roman Church with its bishop is due not to a claim<br />

of superiority over other local churches or to some<br />

will to power cleverly organized over the centuries<br />

by the clergy in the capital of an empire, but rather<br />

to the foundational will of the Lord of the Church.<br />

Peter suffered martyrdom in Rome, and thus his primatial<br />

apostolate devolves upon the Church of Rome<br />

and consequently upon its visible head, the Bishop<br />

of Rome. The primacy of Peter did not flare up at<br />

7

Benedict and Francis<br />

some point over the real world as an ideal, only to<br />

grow dim over the course of history and increasingly<br />

lose its contour in history’s vicissitudes. In order to<br />

comprehend the nature and mission of the episcopal<br />

ministry and of the primacy, one must go beyond a<br />

naturalistic understanding of the Church as a legal<br />

assembly. The Church has its origin in God’s salvific<br />

will and is the instrument thereof. By its nature and<br />

mission it is not merely a religious assembly organized<br />

by men. The dualism between a supratemporal ideal<br />

image and its pale reflection in its historical realization<br />

must be overcome also.<br />

The one mediator, Christ, established and ever<br />

sustains here on earth his holy Church, the community<br />

of faith, hope and charity, as a visible<br />

organization through which he communicates<br />

truth and grace to all men. . . . This is the sole<br />

Church of Christ which in the Creed we profess<br />

to be one, holy, catholic and apostolic, which<br />

our Saviour, after his resurrection, entrusted to<br />

Peter’s pastoral care (Jn 21:17), commissioning<br />

him and the other apostles to extend and rule it<br />

8

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

(cf. Mt 28:18, etc.), and which he raised up for<br />

all ages as “the pillar and mainstay of the truth”<br />

(1 Tim 3:15). (LG 8)<br />

The Church as incarnate reality<br />

Only in terms of the Incarnation is the utter novelty<br />

of the Church revealed to us: it signifies the real and<br />

symbolic presence of the Lord. “Head and body: the<br />

one Christ and the whole Christ” (Augustine, Sermo<br />

341, 1). With this famous formula Augustine, the lifelong<br />

conversation partner and friend of the theologian<br />

Joseph Ratzinger, put the Pauline understanding of<br />

the Church in a nutshell. God is not merely an ideal<br />

of pure reason; neither did Christ merely found an<br />

ideal image of Church. The Second Divine Person assumed<br />

human nature, and by that very fact the visible<br />

communion of the disciples who followed Christ also<br />

became a sacrament that represents and concretely<br />

brings about the supernatural fellowship [Lebensgemeinschaft]<br />

of the faithful (cf. LG 8).<br />

This visible Church, led by the pope and the bishops<br />

in union with him, is the house and people of God,<br />

the Body of Christ, and the Temple of the Holy Spirit.<br />

9

Benedict and Francis<br />

Jesus called specific men by name, so as to give them a<br />

share in His mission and authority (see Mark 3:13–19).<br />

First in the list of the Twelve Apostles mentioned by<br />

name is the fisherman Simon, to whom Jesus gave the<br />

name Peter so as to indicate his permanent role in the<br />

Church. The Incarnate Word of God, Jesus Christ,<br />

humbled Himself in the servile form of His human<br />

body, which was subject to the law of suffering and<br />

death. Part and parcel of this is also the risk of handing<br />

over His mission and authority to men who — trapped<br />

within the limitations of their individuality — may fail<br />

in office, become bogged down in mediocrity, and deny<br />

and betray their Lord. The dark sides of Church history<br />

and the moral failings even of many of the Church’s<br />

highest dignitaries do not justify, however, the retreat<br />

of the faithful into a purely otherworldly ideal Church<br />

or the rejection of the concrete Church by citing an<br />

alleged ideal image of the ancient Church that supposedly<br />

existed in an earlier historical period, or even<br />

the projection of a Church imagined according to one’s<br />

own image and likeness into a utopian future.<br />

Although Christ Himself remained free of sin, He<br />

suffered in His body and redeemed everything human<br />

10

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

that had been disfigured by sin. Christ, the Head of<br />

His Body, “loved the Church and gave himself up for<br />

her, that he might sanctify her, having cleansed her<br />

by the washing of water with the word, that he might<br />

present the Church to himself in splendor, without<br />

spot or wrinkle or any such thing, that she might be<br />

holy and without blemish” (Eph. 5:25–27).<br />

The Church, in her sacramental holiness, which is<br />

not identical with the moral holiness of her members,<br />

is an effective sign of the redemption that has already<br />

been accomplished in Christ, but at the same time — in<br />

the sins and failings of her members — an indication<br />

of all humanity’s need for redemption in the past, the<br />

present, and the future. Therefore when a Catholic<br />

says, “Credo Ecclesiam [I believe the Church],” he does<br />

not mean a mystical, otherworldly, or utopian ideal image<br />

of Church, but rather the concrete Church that is<br />

“at once holy and always in need of purification” (LG<br />

8). The concrete Church “follows constantly the path<br />

of penance and renewal. The Church, ‘like a stranger<br />

in a foreign land, presses forward amid the persecutions<br />

of the world and the consolations of God,’ announcing<br />

the cross and death of the Lord until he comes” (LG 8).<br />

11

Benedict and Francis<br />

Anyone who becomes aware of the full import<br />

of salvation history and of the Incarnation will not<br />

be scandalized by the concrete historical form of the<br />

Church, which, as Pope Francis says, is not only splendid<br />

but also “dented.” He does not flee from the earthly<br />

Church into an abstract ideal that remains untouched<br />

by the dust and dirt of all-too-human behavior. We<br />

do not awaken from a beautiful dream only to be confronted<br />

with miserable reality. True piety does not<br />

dream but places itself bravely and joyfully at the service<br />

of redemption through Christ, who in His Body,<br />

the Church, walks through this real world, with its<br />

hope and joy, but also with its sin and disbelief.<br />

The historical development of the dogmas of<br />

ecclesiology, which includes a deeper understanding<br />

of the episcopal ministry and of the papal primacy,<br />

does not appear in retrospect as a conglomerate of<br />

heterogeneous elements that were cobbled together<br />

by an ideology of power and special interest. It was<br />

instead the intellectual-conceptual and existential<br />

[lebensmässige] unfolding of what is contained in the<br />

revealed faith in the Mystery of the Church, so that<br />

the Church can carry out her mission in ever-new<br />

12

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

societal circumstances and in the challenges of intellectual<br />

and cultural history.<br />

The Petrine ministry as a personal commission<br />

All the words commissioning and sending Simon Peter<br />

that Jesus spoke during His earthly life and work are<br />

spoken personally in each era to the successors of the<br />

first of the apostles on the Chair of Peter. Simon, the<br />

fisherman from the Sea of Gennesaret, was a historical<br />

man, not an ideal artistic figure. This concrete, individual<br />

man with his heritage and life history, with human<br />

strengths and weaknesses, becomes the instrument of<br />

grace, the servant of the Word, and the eyewitness of<br />

the crucified and risen Lord, who promised to remain<br />

always with the Church until the end of the world.<br />

Once near Caesarea Philippi, Peter summarized the<br />

Church’s profession of faith, which is derived from the<br />

revelation by the Father, as follows: “You are the Christ,<br />

the Son of the living God!” Thereupon he hears for<br />

himself and for his successors the promise and the commission:<br />

“And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock<br />

I will build my Church, and the gates of Hades shall<br />

not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the<br />

13

Benedict and Francis<br />

kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 16:16, 18–19). Jesus asks<br />

the whole company of disciples who they think He is,<br />

and Peter answers in his person for all of them. And<br />

Jesus addresses the whole Church in the person of Peter.<br />

In the Cenacle on the night before His death, as<br />

the ultimate fate of all mankind is being decided, Jesus<br />

says to Peter: “And when you have turned again,<br />

strengthen your brethren” (Luke 22:32). He, the Son,<br />

has prayed to the Father with infallible efficacy that<br />

Peter’s faith might not fail and consequently that Peter,<br />

after his conversion, might strengthen his brothers<br />

and sisters in their faith in Christ, the Son of the<br />

living God, the Word of God made flesh.<br />

The risen Lord reveals Himself to the disciples at<br />

the Sea of Tiberias. Three times he asks Peter whether<br />

he loves Him more than these do. Peter is sad to be<br />

reminded in this way of his failure and denial in the<br />

courtyard of the high priest’s house. But this relationship<br />

to Jesus in unconditional trust and unlimited love,<br />

even unto martyrium — witness by his word and by his<br />

life — bestows on Peter a unique authority for the Universal<br />

Church. Jesus says to him three times: “Feed my<br />

lambs. Tend my sheep. Feed my sheep” (John 21:15–17).<br />

14

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

In Peter the popes carry out the pastoral ministry of<br />

Christ, who came to lay down His life for His sheep.<br />

Vatican I, in keeping with the entire Tradition, formulates<br />

it as follows: “Therefore, whoever succeeds Peter<br />

in this chair, according to the institution of Christ<br />

himself, holds Peter’s primacy over the whole Church”<br />

(DH 3057).<br />

All three ecclesiological munera, or offices, that<br />

describe the nature of Peter’s primacy are accompanied<br />

by references to the human limits of Simon Peter,<br />

whether the fact that he tries to separate Jesus’<br />

Messiahship from His suffering in the form of a slave,<br />

or the fact that when his life and reputation are at<br />

risk he publicly evades professing his faith in Jesus,<br />

the Son of the living God.<br />

Again and again, non-Catholic exegesis has tried<br />

to see a relativization of the promise of primacy in<br />

the rebuke of Peter and of his denial, or else in the<br />

incident in Antioch when Paul opposed Peter because<br />

the latter was wrong about the practical consequences<br />

of the fellowship of the circumcised and the uncircumcised<br />

(cf. Gal. 2:11). If that were the case, one<br />

would also have to assume that Christ had allowed<br />

15

Benedict and Francis<br />

Himself to be deceived in His choice of His apostles<br />

or that reality had caught up with His ideal notions, as<br />

though He had failed miserably in founding a Church<br />

as God’s house for all nations.<br />

“But why did Christ in his divine power and omniscience<br />

not choose the wise, the strong, the highly<br />

regarded to be his apostles, bishops, and popes?” we<br />

of little faith ask all too humanly, and we get the answer<br />

from Paul: “So that no flesh might boast in the<br />

presence of God” (1 Cor. 1:29). But in keeping with<br />

God’s grace, the apostles are like master builders of<br />

God’s house, which once and for all has its foundation<br />

on Christ. Those who come after the apostles should<br />

take care how they continue to build upon it — with<br />

gold and silver, precious stones, or with wood, hay, and<br />

straw (cf. 1 Cor. 3:10ff.). The last word about another<br />

person, and even about a pope, belongs to no one but<br />

God, for He alone judges rightly and justly. Everyone<br />

should collaborate in building up the kingdom of God,<br />

each according to the measure of the grace and natural<br />

talent he has received. Only in God’s tribunal is judgment<br />

passed on our work as “God’s fellow workers” (1<br />

Cor. 3:9) and “fellow workers in the truth” (3 John 8).<br />

16

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

Thus we can understand every pontificate of a pope<br />

as a stretch of Church history, as a specific realization<br />

of the permanent Petrine primacy — mediated<br />

through the personality of him who has been called<br />

by God Himself to build up His house.<br />

Religiously and theologically speaking, it makes<br />

little sense to compare the individual persons on the<br />

Chair of Peter and their pontificates with one another<br />

according to worldly criteria. The decisive thing is the<br />

relation to the primacy of Peter, which must be the<br />

measure and guide of every pope. For, strictly speaking,<br />

every pope is the successor of Peter and not just<br />

of his chronological predecessor.<br />

Joseph Ratzinger — Pope Benedict XVI<br />

One important characteristic of the pontificate of<br />

Benedict XVI was his extraordinary theological talent.<br />

By this I mean not simply skills resulting from<br />

his professorial activity, but the great originality of<br />

his theology on the most important themes of the<br />

doctrine of the Faith. What is true of every Christian<br />

in general is true also about popes in particular: the<br />

most varied charisms are given by the Spirit of God<br />

17

Benedict and Francis<br />

so that they might benefit others, and thus the Body<br />

of Christ is built up in the knowledge and love of<br />

God. Thus, in the collaboration of its members, the<br />

whole Body grows toward the fullness of Christ, so as<br />

to become the perfect man. Let him who has received<br />

the gift of teaching teach! — “in proportion to our<br />

faith” (Rom. 12:6–7).<br />

This analogy of faith, the insight into the inner<br />

connection between revealed truth and the goal of<br />

salvation for every person, is based on the analogy of<br />

being, that is, on the truth-capability of created reason<br />

also, which recognizes in what really exists in the<br />

world the esse, verum, et bonum [being, the true, and<br />

the good], which in turn are the mirror and likeness<br />

of God’s reason and love. On the basis of the analogia<br />

entis, theology is possible as the science of revealed<br />

faith according to the analogia fidei.<br />

Theological knowledge does not cater to the intellectual<br />

curiosity that preens in the private club of<br />

a few specialists and delights in its own intelligence.<br />

Without the constant exchange with theology, as it<br />

has been developed by the Fathers of the Church and<br />

by the great theologians of the Middle Ages and the<br />

18

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

modern era in a wide variety of schools, the Magisterium<br />

could not live up to its responsibility. For the<br />

Church’s Magisterium testifies to the revealed Faith of<br />

the Church in the Creed, the auditus fidei [the hearing<br />

of the faith], whereas the intellectual presentation<br />

thereof is accomplished rationally and conceptually,<br />

so that the intrinsic reasonableness of the entire depositum<br />

fidei comes to light in theological reflection<br />

and becomes fruitful in preaching and pastoral care.<br />

Certainly, in its authority the Magisterium, as an<br />

authentic witness to revelation by virtue of the assistance<br />

of the promised Holy Spirit, is superior to<br />

academic theology, but at the same time it makes use<br />

of the latter out of an inner necessity. The Pope and<br />

bishops can correctly and completely teach and present<br />

for belief only those things and all those things<br />

that are contained in God’s historical revelation. As<br />

for the linguistic and conceptual form, however: “The<br />

Roman Pontiff and the bishops, by reason of their office<br />

and the seriousness of the matter, apply themselves<br />

with zeal to the work of enquiring by every suitable<br />

means into this revelation and of giving apt expression<br />

to its contents; they do not, however, admit any new<br />

19

Benedict and Francis<br />

public revelation as pertaining to the divine deposit of<br />

faith” (LG 25). For the Pope and the bishops, unlike<br />

Peter and the other apostles, are not personally bearers<br />

of revelation. Nor do they receive any inspiration, as<br />

the authors of Sacred Scripture did; rather, they are<br />

bound by the testimony of the word of God in Scripture<br />

and Tradition. In truly handing on the Faith in<br />

their teaching office, however, they enjoy the assistance<br />

of the Holy Spirit (assistentia Spiritus Sancti).<br />

Even Peter in his first letter, an “Encyclical,” exhorted<br />

Christians and especially priests and bishops to<br />

have an answer ready for anyone who asks about the<br />

“Logos of hope” (cf. 1 Pet. 3:15) that is ours through<br />

faith in Christ the Lord, “the Shepherd and Guardian<br />

of your souls” (1 Pet. 2:25).<br />

A major theme of Joseph Ratzinger, not only as a<br />

theologian but also as the Prefect of the Congregation<br />

for the Doctrine of the Faith and as the Pope,<br />

with different responsibilities in each instance, was<br />

to point out the intrinsic connection between faith<br />

as hearing and as understanding, between the auditus<br />

fidei and the intellectus fidei. Here the faith is not<br />

measured by an external standard and subjected to a<br />

20

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

criterion that is foreign to it, as in the rationalistic<br />

concept of reason that is reduced to feasibility. One<br />

cannot study philosophy, history and the social sciences<br />

more geometrico [in a geometric fashion]. Faith<br />

as enlightenment by the light of Christ (lumen fidei)<br />

is, instead, reasonable in itself, in keeping with the<br />

Logos of God — a rationabile obsequium [rational worship]<br />

(cf. Rom. 12:1). To academic theology belongs<br />

the task of mediating between the knowledge of God<br />

in faith and the knowledge of the world through natural<br />

reason (lumen naturale), as it is presented in the<br />

natural sciences and the humanities, so that in the<br />

consciousness of believers the truths of the faith and<br />

natural knowledge do not fall apart but, rather, form<br />

a new synthesis in every age.<br />

Of course one cannot reduce the entire work of<br />

a pontificate to a single priority, and anyway it is<br />

reserved to God alone to judge the fruitfulness of it.<br />

But the theological elaboration of the intrinsic unity<br />

and interdependence of faith and reason is nevertheless<br />

one aspect that lends a particular character to<br />

the pontificate of Benedict XVI. Faith and reason<br />

are not mutually limiting or mutually exclusive but<br />

21

Benedict and Francis<br />

rather serve the perfection of man in God and in His<br />

Word, which assumed our flesh, and in His Spirit,<br />

who reveals the most profound being and life of God:<br />

God is love, as the great Encyclical Deus caritas est<br />

explains.<br />

So we can say: Benedict XVI was one of the great<br />

theologians on the Chair of Peter. In the long series<br />

of his predecessors a comparison suggests itself with<br />

the outstanding scholarly figure of the eighteenth<br />

century, Pope Benedict XIV (1740–1758). Likewise<br />

one will think of Pope Leo the Great (440–461), who<br />

formulated the decisive insight for the Christological<br />

profession of the Council of Chalcedon (451). In the<br />

long years of his academic work as a professor of fundamental<br />

and dogmatic theology, Benedict XVI accomplished<br />

independent theological work that places<br />

him in the ranks of the most important theologians<br />

of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For more<br />

than fifty years the name Joseph Ratzinger has stood<br />

for an original comprehensive outline of systematic<br />

theology. His writings combine scholarly knowledge<br />

of theology with the living form of the Faith. As a<br />

science that has its genuine place within the Church,<br />

22

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

theology can show us the special destiny of man as<br />

God’s creature and image.<br />

In his scholarly works, Benedict XVI could always<br />

fall back on a marvelous knowledge of theological<br />

and dogmatic history, which he conveyed in such a<br />

way that God’s vision of man, which supports everything,<br />

comes to light. This is made accessible to<br />

many people by Joseph Ratzinger’s use of [Umgang<br />

mit] words and language. Complex subjects are not<br />

made incomprehensible to the average reader by a<br />

complicated presentation; instead these matters are<br />

made transparent, revealing their inner simplicity.<br />

The point is always that God wants to speak to every<br />

person, and His Word becomes a light that enlightens<br />

every man (cf. John 1:9).<br />

Faith and reason<br />

To point out only one of the groundbreaking theological<br />

speeches of the Pope, I would like to mention the<br />

Regensburg Lecture from the year 2006. In it Benedict<br />

XVI once again emphasized the intrinsic connection<br />

between faith and reason. Neither reason nor<br />

faith can be thought of independently of the other<br />

23

Benedict and Francis<br />

and still achieve its real purpose. Reason and faith<br />

are protected from dangerous pathologies by mutual<br />

correction and purification. Benedict XVI thereby<br />

connects with the great tradition of the theological<br />

sciences, which, in the overall structure of the university,<br />

can prove to be the element that binds everything<br />

together.<br />

The encyclical Fides et ratio by John Paul II comes<br />

to mind whenever there is a discussion of the tragic<br />

developments in European intellectual life. In nominalism<br />

a voluntaristic picture of God had developed.<br />

In order to remove God entirely from the reach of our<br />

metaphysical reason, He was thought of as sheer will,<br />

which man must accept in blind obedience, without<br />

any possibility of understanding Him rationally. In<br />

opposition to Him, man had to declare his autonomy<br />

so as to ensure his freedom. Modern atheism as humanism<br />

without or against God has one of its roots<br />

in a theological aberration. But if God Himself is reason<br />

and will, word and love, then the knowledge of<br />

God and our understanding of the world, nature and<br />

grace, reason and freedom do not come into conflict<br />

but rather prove to be the expression of the personal<br />

24

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

communion of God and man in Jesus Christ, the Godman.<br />

God is not man’s rival, but rather the fulfillment<br />

of all searching for truth and for the perfection of man<br />

in freedom as love and self-gift [Hingabe].<br />

The figure of Jesus of Nazareth<br />

The fortunate combination of the Pope as the universal<br />

teacher of the Faith with the theological thinker<br />

Joseph Ratzinger probably appears most convincingly<br />

in his three-volume work, Jesus of Nazareth.<br />

As the successor of Peter, the Pope professes the<br />

revealed truth, which goes beyond natural reason,<br />

that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah, the Son of the<br />

living God. The theologian Ratzinger, based on his<br />

lifelong study of the question of Jesus in historical<br />

criticism, has at his disposal the intellectual means<br />

of making very clear, that is, of communicating intellectually<br />

the consistency and inner truth of the fact,<br />

that the Jesus of history is identical with the Divine<br />

Word made flesh who is recognized in faith.<br />

Joseph Ratzinger’s lifework culminates in his book<br />

on Jesus. With his three volumes on Jesus he has stimulated<br />

a vigorous discussion about Jesus of Nazareth,<br />

25

Benedict and Francis<br />

whom Christians profess as the universal Savior and<br />

the sole Mediator between God and mankind. In this<br />

individual man, Jesus of Nazareth, God definitively<br />

and irreversibly made the historical coincidence of divine<br />

revelation and human self-surrender to the Father<br />

become a concrete event. Hence we profess with the<br />

Church that Jesus is the Christ, in whom it becomes<br />

possible for mankind to experience the historical salvific<br />

presence of God. He is the one who accomplishes the<br />

Father’s will and wishes to lead all mankind along the<br />

way to the knowledge of the truth (cf. 1 Tim. 2:4–5).<br />

In the New Testament we find the formation of<br />

the apostolic Church’s profession of faith, which is<br />

achieved in the living faith of the disciples; this faith<br />

originated in the encounter with Jesus of Nazareth as<br />

a historical person, with the words of His preaching<br />

of the kingdom of God, and in the experience of His<br />

death and Resurrection from the dead. In the event<br />

on Easter morning and in light of God’s self-revelation<br />

in His Son, the believer meets with a person<br />

who is his Creator and Perfecter: Jesus Christ is the<br />

Lord whom we profess in faith, the Lord and Head<br />

of His Church.<br />

26

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

In its epilogue, the Gospel of John mentions the<br />

justification for its composition and for the Church’s<br />

entire witness to the Faith in Scripture and Tradition,<br />

so as to oppose all attempts to read the Gospel as a<br />

simple historical biography. The purpose is not merely<br />

to give information about a person, but rather it was<br />

written “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ,<br />

the Son of God, and that believing you may have life<br />

in his name” (John 20:30–31).<br />

This look at the six decades of intensive intellectual<br />

and scholarly penetration of the various themes<br />

of Christology in the theological work of Joseph Ratzinger<br />

brings to light the continuity of his thought.<br />

His long wrestling with the figure of Jesus, which he<br />

himself formulates in the first volume of the trilogy<br />

on Jesus can be traced through his writings. From the<br />

very beginning he asks himself the question: “Who is<br />

Jesus of Nazareth” — for men, for the world? 1<br />

1<br />

Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth,<br />

trans. Adrian J. Walker (New York: Doubleday,<br />

2007), 6.<br />

27

Benedict and Francis<br />

He decisively opposes an attitude of skepticism<br />

that considers God incapable of revealing himself definitively,<br />

and he shows a fine sense of the ideological<br />

constraints that may monopolize people’s attention.<br />

With the clarity that can be derived from the<br />

Church’s profession of faith, he develops from historical<br />

findings and the Gospel accounts an inviting overall<br />

view of Jesus of Nazareth that stimulates further<br />

reflection. On the basis of the historically consolidated<br />

formulations of the Christological dogmas, as<br />

they were formulated in the great ecumenical councils<br />

of Nicaea and Chalcedon, Joseph Ratzinger develops<br />

his approaches to Christology and to Catholic<br />

theology as a whole, which now are being presented<br />

synoptically in the sixteen volumes of his Collected<br />

Works in German [Gesammelte Schriften].<br />

Finally, in looking to the crucified and risen Lord<br />

Jesus, man finds his ultimate fulfillment in the one<br />

“whom God made our wisdom, our righteousness and<br />

sanctification and redemption” (1 Cor. 1:30), “in whom<br />

are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge”<br />

(Col. 2:3). Until the second coming of Christ, Peter<br />

unites the many disciples in their profession of the<br />

28

The Primacy of Peter in the Pontificate of Benedict XVI<br />

one Faith: You are Christ, the Son of the living God.<br />

This is the mission of the papacy for the Church and<br />

for the world.<br />

The primacy — quotations and thoughts<br />

In the Decretum Gelasianum, some parts of which go<br />

back to a set of documents compiled by Pope Damasus<br />

I (366–384), the primacy of the Roman Church<br />

(i.e., of the pope with the clergy and the people) is<br />

justified not politically by the rank of the capital and<br />

residential cities of the Roman Empire, but rather in<br />

strictly ecclesiological terms; it is derived Christologically<br />

from the authority of the Lord of the Church:<br />

After [all these] prophetic and evangelical and<br />

apostolic writings [which we have set forth<br />

above], on which the Catholic Church by the<br />

grace of God is founded, we have thought this<br />

(fact) also ought to be published, namely, that,<br />

although the universal Catholic Church spread<br />

throughout the world is the one bridal chamber<br />

of Christ, nevertheless the holy Roman Church<br />

has not been preferred to the other Churches<br />

29

Benedict and Francis<br />

by reason of synodal decrees, but she has obtained<br />

the primacy by the evangelical voice of<br />

the Lord and Savior, saying: You are Peter, and<br />

on this rock I will build my Church. (DH 350)<br />

The conviction that Jesus Christ, the Head of the<br />

Church speaks in Peter to each of his successors “day<br />

in and day out” (Sermo III, 3) the words: “You are Peter<br />

and on this rock I will build my Church,” and that<br />

in every pope, even if he should be personally unworthy,<br />

Peter professes on behalf of the whole Church:<br />

“You are the Christ, the Son of the living God,” is<br />

expressed poignantly by Pope Leo the Great in a solemn<br />

sermon “On the Anniversary of His Elevation<br />

to the Pontificate”: “Just as what Peter believed about<br />

Christ is always valid, so too what Christ instituted in<br />

Peter continues forever” (Sermo III, 2). And therefore<br />

this feast is celebrated with the right disposition “if<br />

everyone sees and honors in my person the one (i.e.,<br />

Peter) who eternally unites in himself the concerns of<br />

all pastors with his custody over the sheep entrusted<br />

to him and even in the case of an unworthy successor<br />

loses none of his dignity” (Sermo III, 4).<br />

30

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

Truth and Freedom:<br />

What Does Laicity<br />

Mean for Christians?<br />

Paris, Académie Catholique de France,<br />

March 26, 2015<br />

31

As a child and a youth in the postwar period, I<br />

had the good fortune and the grace to grow<br />

up in the young democracy of the Federal Republic<br />

of Germany. The stories our grandparents told<br />

about the First World War and our fathers told about<br />

the National Socialist dictatorship and the horrors<br />

of World War II were ever present in our mind and<br />

imagination. We were shaped and positively attuned<br />

to the future, however, by other events and images.<br />

I am thinking about the meeting between Konrad<br />

Adenauer and Charles de Gaulle in the cathedral in<br />

Rheims, when the representatives of the two states<br />

extended their hands to each other — a symbol of<br />

reconciliation, which should be understood most<br />

profoundly as an expression of a Christian way of<br />

thinking. Hereditary enmity and rivalry are no longer<br />

the keys to a common house of Europe and for the<br />

33

Benedict and Francis<br />

worldwide family of nations, but rather friendship and<br />

trust. I like to remember the German-French youthexchange<br />

program in which I participated with our<br />

whole class in Alsace. We experienced and learned<br />

that different languages and cultures do not alienate<br />

us, but rather enrich us, and they can bring about a<br />

happy sense of expanding one’s intellectual horizons.<br />

The intellectual cosmos of Catholic life is unimaginable<br />

without French history, literature, philosophy, and<br />

theology. Henri Blondel, Étienne Gilson, Henri de<br />

Lubac, Yves Congar, Louis Bouyer, and Jean Daniélou<br />

became friends of mine who accompanied my journey<br />

as a European citizen and a Catholic Christian.<br />

The Christian faith does not alienate us from life<br />

and modern culture. In the encounter with Jesus Christ,<br />

who proclaimed the kingdom of God and made it real<br />

through His Cross and Resurrection, God reveals Himself<br />

as the origin and goal of every man. The mystery<br />

of man is truly elucidated only in the mystery of the<br />

Incarnate Word (cf. Gaudium et spes [GS] 22). Faith<br />

in the transcendent God (“Glory to God in the highest”)<br />

and responsibility for the immanent world (“peace<br />

on earth”) intrinsically belong together in Christ, the<br />

34

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

God-man. The hope that there will be justice in eternal<br />

life for the victims of injustice and violence obliges<br />

Christians to serve the poor and to work for peace and<br />

justice in this world. Wholehearted love for God and<br />

love of neighbor as oneself are the heart of Christian<br />

life (see Mark 12:29–31). The God of truth guarantees<br />

and promotes human freedom, which is perfected in<br />

love. “If you continue in my word, you are truly my<br />

disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth<br />

will make you free” (John 8:31–32).<br />

Lessons from history<br />

The political ideologies of National Socialism and<br />

Communism — the latter did not fall in Eastern Europe<br />

until 1989 — taught us that opposition to the<br />

truth is not the humble search for it, but rather a lie<br />

that destroys the trust that is necessary as the foundation<br />

of every society. And freedom is far more than<br />

the absence of compulsion and force, or even the<br />

opportunity to follow my impulses and interests exclusively.<br />

True freedom is freedom for the good and<br />

liberation for an unconditional commitment to the<br />

good. In every truth that is acknowledged, God is<br />

35

Benedict and Francis<br />

implicitly acknowledged, and in every good that is<br />

done, a person aims at God’s goodness. Freedom presupposes<br />

the internal and external possibility of living<br />

according to one’s conscience, doing good for its own<br />

sake, and not obeying immoral and criminal orders.<br />

We must draw two lessons from the catastrophes<br />

of the twentieth century that were brought on by the<br />

relativization of truth and morality and the absolutization<br />

of state, nationality, and race:<br />

1. The inalienable dignity, the essential equality,<br />

and the rights and duties of all men must<br />

always be respected.<br />

2. As understood by social justice, a share in the<br />

earth’s resources and in cultural goods must<br />

be made possible for all men (cf. GS 39).<br />

From these it follows that ethical principles must be<br />

universally valid and must never be subordinated to<br />

the interests of a nation, a class, or a religious or ideological<br />

group.<br />

Based on our experience, first with the mentality<br />

that favored the authoritative state in Prussia<br />

and then with two misanthropic, godless dictatorships,<br />

we in Germany are skeptical about any form<br />

36

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

of governmental omnipotence. The state is relatively<br />

necessary for the common good. Nevertheless in its<br />

legislative, executive, and judicial authority it must<br />

never claim absolute control over the intellectual<br />

and moral life of the citizens. The state is not above<br />

the conscience of its citizens, and it is not above the<br />

natural moral law. It is not the master of its citizens,<br />

and it does not own the land. The state exists for<br />

persons and for society. It has to regulate the temporal<br />

concerns of its citizens and guarantee respect<br />

for fundamental human rights. Conversely, a societal<br />

group must not take control of the state in order to<br />

favor a prevailing ideology through the opportunities<br />

offered by school education, university formation,<br />

or the news media. State control of the mainstream<br />

media not only betrays a mentality in favor of the<br />

authoritative state, but also contradicts the human<br />

right to objective information and freedom of opinion.<br />

People must not suffer discrimination and restriction<br />

of their civil freedoms merely because they<br />

oppose a momentarily dominant ideology.<br />

The modern democratic state, which on the basis<br />

of freedom of religion and freedom of conscience<br />

37

Benedict and Francis<br />

faces a pluralistic society, not only acknowledges the<br />

individual citizen as a partner, but also must develop<br />

a partnership with the religious and civic groups in<br />

civil society. Since man is a social being, freedom of<br />

religion too can never be interpreted in a merely individual<br />

sense, but necessarily has a social component.<br />

Therefore one inviolable human right is people’s freedom<br />

to join together in a religious community with a<br />

common profession of their fundamental intellectual<br />

and moral principles, with common public worship<br />

and an independently drawn-up constitution for the<br />

community. These individuals must not be forbidden<br />

to participate in public life on an equal footing, and<br />

the state must recognize their activity for the common<br />

good. The state cannot make Christianity or Islam or<br />

any other community the state religion, nor can it<br />

officially adopt agnosticism or atheism and relegate<br />

dissenters to the status of a merely tolerated minority.<br />

This is a matter of genuine equal treatment. If it<br />

favors one, it inevitably disadvantages the others. The<br />

creed of the nineteenth-century liberals and socialists,<br />

whose ethics and teaching about the state were<br />

directed toward the interests of their own class, along<br />

38

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

with twentieth-century forms of political absolutism,<br />

consolidated in the axiom: Religion is a private matter.<br />

That statement, however, fundamentally contradicts<br />

individual and social human rights. What right does a<br />

citizen have to say: “My view of the world is scientifically<br />

superior to yours; I consider you less enlightened<br />

than myself, and therefore my hermeneutical and ethical<br />

principles will define public life in politics, science,<br />

public life, and culture”? What group has the right to<br />

decree, “The place for our opinions is the public forum,<br />

and the place for your intellectual and moral convictions<br />

is your private residence. Behind the walls of<br />

your church you can say what you like, but the street<br />

in front of the church belongs to us”?<br />

Since the eighteenth century there has been a<br />

peculiar restriction of the acknowledgment of truth,<br />

while agnosticism has been made into an absolute. Is<br />

it possible, though, to prove philosophically that human<br />

reason as a matter of principle is incapax infiniti,<br />

incapable of grasping the infinite? How can anyone<br />

try a priori to rule out the possibility that finite, created<br />

reason can be elevated by God to participate in<br />

His reason through the mediation of His Word, which<br />

39

Benedict and Francis<br />

became flesh? It is the nature of reason to be ordered<br />

to truth, and it is part of the dynamic of freedom to<br />

be united with the good in love. No one can take<br />

from the Church the freedom to bear witness and to<br />

testify publicly: “Grace and truth came through Jesus<br />

Christ. No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten<br />

Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has made<br />

him known” (John 1:17–18).<br />

The dramatist Lessing, with his parable of the<br />

ring [in the comedy Nathan the Wise] did not prove<br />

that there can be no sure knowledge of revelation<br />

and that religions can therefore have only moral and<br />

humanitarian, i.e., functional usefulness. He merely<br />

illustrated his agnostic position without proving its<br />

universal validity. Kant by no means disproved once<br />

and for all the possibility of metaphysics, but only<br />

pinpointed the impossibility of bridging the gap between<br />

rationalism and empiricism. Feuerbach, who<br />

considered faith in God to be a projection that alienates<br />

man from his nature, overlooked the fact that<br />

the events of historical revelation are not derived<br />

idealistically from the individual and collective consciousness<br />

of believers, and consequently his whole<br />

40

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

argument just begs the question. Auguste Comte’s<br />

law of three stages is his subjective schema with<br />

which he tries to brand intellectual history, without<br />

taking into account the spontaneity of philosophical<br />

knowledge, which is qualitatively different from<br />

the knowledge of empirical things. Nor is religion by<br />

any means — Marx and Lenin notwithstanding — the<br />

“opium of the people.”<br />

Religion, the worship of God, the Creator and Father<br />

of all men, is instead the most profound source for<br />

the humanity and respect of our neighbor as a brother<br />

or a sister, in whose sufferings and needs Christ Himself<br />

meets me. Respect for freedom of religion and<br />

freedom of conscience forbids legal discrimination<br />

against or persecution of citizens with equal rights<br />

who belong to a particular religious community or to<br />

Christ’s Church. The state is not religious or atheistic;<br />

rather it must be neutral with regard to worldviews.<br />

The modern state does not govern civil society as an<br />

authoritative state, but rather ensures the free space<br />

for the involvement of its citizens and free associations.<br />

For this reason it must not only ensure the equal<br />

treatment of religious communities and associations<br />

41

Benedict and Francis<br />

that represent a worldview, but must also promote the<br />

constructive involvement of its citizens for the benefit<br />

of society in all areas.<br />

Laicism and laicity<br />

Someone who does not come from the Romance culture<br />

in Belgium, France, or Italy has difficulties at first<br />

with a laicist worldview of the state, which declares<br />

itself to be the supreme norm of public discourse and<br />

consequently makes itself absolute vis-à-vis pluralistic,<br />

free society. In Germany, this term and the concept<br />

of the state behind it cannot be translated literally.<br />

“Separation of church and state” has no hostile undertone<br />

there, but rather means mutual respect for<br />

the different responsibilities and consequently cooperation<br />

— for instance, in education and in the field<br />

of social services and charitable works. The common<br />

goal is the common good. If a school or a hospital that<br />

is owned privately or even by the Church is partially<br />

financed by tax revenues, the ones who are acting<br />

generously are not the politicians, but the citizens,<br />

who with their taxes help to support the institutions<br />

that benefit everyone.<br />

42

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

In Europe we face the challenge of rethinking the<br />

various traditions for determining the relationship<br />

between the state and the Church or the non-Christian<br />

religious communities. The ideological power struggle<br />

over the European Constitution, in which the<br />

mere mention of the religious and Christian roots of<br />

European culture was rejected by so-called laicism,<br />

must not be repeated. It is always a sign of ideological<br />

narrow-mindedness when historical facts are denied.<br />

All the citizens in a pluralistic society should participate<br />

on an equal footing, and on this basis we must<br />

find a constructive relation of states to communities<br />

of believers or of persons who share a worldview.<br />

The laicity of the state needs a new, positive definition<br />

if society is not to be robbed of the intellectual,<br />

moral, and charitable resources that come from man’s<br />

religious predisposition and from the historical religions.<br />

For citizens cannot be compelled by state laws<br />

to embrace moral principles and to practice solidarity<br />

if people’s consciences are not formed by moral philosophy<br />

(“the categorical imperative”) and religion<br />

(“I am the Lord, thy God. Thou shalt . . .”) in such a<br />

way that they acknowledge the fundamental moral<br />

43

Benedict and Francis<br />

law: good must always be done for its own sake, and<br />

evil must be avoided unconditionally.<br />

The concept laikos (First Letter of Clement 40, 5)<br />

in the Christian context has had a positive meaning<br />

from the beginning. The layman is the Christian as<br />

citizen of the kingdom of God and member of the<br />

household in the Lord’s family, as believer in Christ<br />

and person filled with God’s Spirit who enjoys “the<br />

glorious liberty of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21).<br />

Through faith and Baptism, Christians have been<br />

included in the People of God. The doctrine of the<br />

common royal priesthood emphasizes the equal dignity<br />

of all baptized persons as well as their duty to<br />

testify by word and deed to God’s universal salvific<br />

will for all men and to proclaim the Gospel (see 1<br />

Pet. 2:5, 9).<br />

The Church as the communion of salvation in<br />

Christ, the High Priest of the New Covenant and the<br />

bearer of hope for every man, is not divided thereby<br />

into two classes, so that a few from the company of<br />

disciples are appointed shepherds by Christ Himself<br />

and lead the pilgrim People of God to meet the Christ<br />

who is to come. The whole Church, as one salvific<br />

44

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

communion in Christ, is the sacrament of salvation<br />

for the world (see LG 1).<br />

The faithful (priests, religious, and laity) are citizens<br />

of the one People of God, and the clergy are<br />

holders of a sacred authority for the entire Church; a<br />

note of opposition crept into this ecclesially defined<br />

view when societal and political developments were<br />

superimposed on the theological terminology. Think<br />

of the educational offensive of the Carolingian Renaissance.<br />

After the collapse of the Roman Empire,<br />

the intellectual achievements of the Greco-Roman<br />

culture and the great patristic heritage were preserved<br />

chiefly in the cloisters and passed on to the empires<br />

that arose after the barbarian invasions. Bishops in<br />

governmental service, monks and priests in cathedral<br />

and monastic schools and in the later universities of<br />

the High Middle Ages were responsible for education<br />

and science, while “layman” became the designation<br />

for the uneducated. Over the long term this resulted<br />

in a drive to emancipate the laity from the educational<br />

monopoly of the clergy. From the fifteenth century<br />

onward, this was connected with a certain anticlericalism.<br />

The Protestant Reformation considered itself to<br />

45

Benedict and Francis<br />

be the rediscovery of the dignity of the layman (“We<br />

are all priests in like manner”), and by way of its anticlerical,<br />

anti-Roman sentiment it was able to make<br />

its concerns plausible to a broad populace. In contrast,<br />

the Catholic Church in the Tridentine Reform<br />

strengthened the hierarchical structure of the Church.<br />

A political form of anticlericalism first developed<br />

against the papal universal monarchy in temporal matters<br />

in the Investiture Controversy in Germany. In<br />

France the tendency to set the state over the Church<br />

began symbolically with the attempt by Guillaume de<br />

Nogaret, the Chancellor of King Philip IV, to arrest<br />

the Pope in Anagni (September 7, 1303). This was<br />

supposed to break the political power of the clergy<br />

and to subject the Church to the state. The Church<br />

became an instrument of absolutism. The Edict of<br />

Fontainebleau (1685), with which King Louis XIV<br />

revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had called for<br />

tolerance, was not only an act of violence against the<br />

religious liberty of the Reformed Christians but also<br />

an abuse of the Catholic Faith, which was forced to<br />

serve the ideology of France’s absolutist unity (“State<br />

religion”: un roi, une loi, une foi [one king, one law,<br />

46

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

one faith]). The Declaration of the Rights of Man<br />

and of the Citizen (1789) and the 1791 Constitution<br />

could only be welcomed as a victory over the religious<br />

persecution of minorities, even though they were later<br />

thwarted during the Jacobin Reign of Terror. The anticlericalism<br />

of the French Revolution was aimed at the<br />

religious and Christian trimmings of state absolutism,<br />

but it maintained the absolute character of the state<br />

and even heightened it, because it no longer recognized<br />

any higher moral authority to which rulers had<br />

to answer in conscience.<br />

The liberal anticlericalism in the nineteenth century<br />

saw its mission as the exploitation of state and<br />

culture to liberate enlightened citizens, the “nonclerics”<br />

— precisely the “laity” — from “rule by priests”<br />

and “religiously caused ignorance of the masses.” The<br />

secularization of Church property, the disbanding of<br />

cloisters and monasteries, keen supervision of pastoral<br />

work and preaching by state officials, and a constitutional<br />

oath as a prerequisite for pastoral activity were<br />

considered a boon for mankind by those who were<br />

politically responsible for the culture wars in Italy and<br />

Germany and by the champions of the laicist laws<br />

47

Benedict and Francis<br />

establishing the Separation of Church and State in<br />

France (1905) and in other countries. In how many<br />

formerly Christian states of Europe did laicism lead<br />

to the open persecution of Christians — and even to<br />

the plan to eradicate Christianity and above all the<br />

Catholic Church?<br />

What a transformation: from the originally positive<br />

concept of the layman as someone called to be a citizen<br />

in the kingdom of God, to laicism as an ideological-political<br />

movement fighting against the Church!<br />

Both within the Church and in the Church’s relations<br />

with the non-Christian world, we must overcome the<br />

harmful battle between clericalism and laicism, which<br />

has been and still is responsible for so many infringements<br />

of freedom of conscience and for violations of<br />

human dignity. Society, politics, and culture need to<br />

be de-ideologized and liberated from the mania of dividing<br />

people into the categories of revolutionary and<br />

reactionary, right and left, liberal and conservative,<br />

and so forth. Ideologies always aim to marginalize their<br />

alleged opponents. Faith and reason, nevertheless, are<br />

founded on the recognition of the dignity of the other<br />

and of his otherness, and they motivate us to solidarity<br />

48

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

and to common action for the common good. Mere<br />

tolerance as mortar binding the individuals in a pluralistic<br />

society is not enough. Much more is required: willingness<br />

to understand the other and preexistence (being<br />

for others) (Dietrich Bonhoeffer), and the cooperation<br />

of everyone for peace between nations, for the freedom<br />

of every person, and for the political and economic<br />

participation of millions of poor people in the material<br />

and spiritual goods that belong to mankind as a whole.<br />

Church and State according<br />

to the Second Vatican Council<br />

In the gradual development of a positive definition<br />

of the laicity of the state, the Second Vatican Council<br />

has epochal significance. The great challenges of<br />

the present and the future confronting all mankind<br />

cannot be met with a continuation of the ruinous<br />

ideological trench-fighting of the past.<br />

First of all, within the Church the connotation<br />

of merely passive membership in the Church that<br />

has been associated with the term layman since the<br />

early Middle Ages has been overcome. The Decree on<br />

the Apostolate of the Laity Apostolicam actuositatem<br />

49

Benedict and Francis<br />

adopts the new overall approach to ecclesiology and<br />

puts it into concrete terms. The wider context is, as<br />

the Constitution on the Church Lumen gentium elaborates,<br />

an understanding of the Church in the mystery<br />

of God’s universal salvific will and thus also the depiction<br />

of the Church as the People of God, as the Body<br />

of Christ and the Temple of the Spirit, as sacrament of<br />

the most intimate union of men with God and sacrament<br />

of the unity of mankind. The special ministry of<br />

bishop, priest, and deacon — in contrast to the participation<br />

of all in the Church’s overall mission — is<br />

justified not functionally (in the Protestant sense)<br />

but rather sacramentally (in the Catholic sense). It<br />

is a matter of carrying out one mission with various<br />

forms of authority and charismatic gifts.<br />

In connection with our topic, however, we must<br />

now turn to the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et spes,<br />

which essentially was prepared by French theologians.<br />

In it the Council addresses all people of goodwill,<br />

including atheists, to offer them an honest dialogue<br />

about the momentous topics of peace and war, about<br />

the immense potential of science and technology, and<br />

about the future of the human family. And no one<br />

50

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

can look away when people are starving, deprived of<br />

their rights, and enslaved in growing numbers, when<br />

the tragedy of refugees advances into the European<br />

house, and the globalization of opportunities and risks<br />

has become the greatest challenge for the world. The<br />

Church in today’s world is not a special-interest group<br />

that lobbies for its own interests alone. Everything<br />

that Gaudium et spes says “about the dignity of the<br />

human person, the community of mankind, and the<br />

deep significance of human activity provides a basis<br />

for discussing the relationship between the Church<br />

and the world and the dialogue between them” (GS<br />

40). The Church therefore is offering not only dialogue<br />

but also collaboration in building the fraternal<br />

fellowship that corresponds to man’s noble, divine<br />

vocation. “The Church is not motivated by an earthly<br />

ambition but is interested in one thing only — to carry<br />

on the work of Christ under the guidance of the Holy<br />

Spirit, for he came into the world to bear witness to<br />

the truth, to save and not to judge, to serve and not<br />

to be served” (GS 3).<br />

This is also a major theme in the pontificate of<br />

Pope Francis: “A poor Church for the poor.” The<br />

51

Benedict and Francis<br />

Church is poor in the totality of the faithful laypeople<br />

and their pastors who see themselves as following<br />

their Lord in His mission. Church property should not<br />

be given up, as idealists and enthusiasts demand, but<br />

rather used with great determination as a means to<br />

an end, namely, the fulfillment of the Church’s pastoral<br />

and charitable works. “The poor” are all persons<br />

in their existential need and material neediness, to<br />

whom Christ proclaims the gospel (see Luke 4:18).<br />

The whole drama of human history — the human<br />

condition, its hopes and disappointments, its joys and<br />

sorrows, love and death, man as a creature and in his<br />

God-given vocation to eternity, the whole mystery<br />

of man — finds in Christ its solution and redemption<br />

[Lösung und Erlösung]: “And that is why the Council,<br />

relying on the inspiration of Christ, the image of the<br />

invisible God, the firstborn of all creation, proposes to<br />

speak to all men in order to unfold the mystery that<br />

is man and cooperate in tackling the main problems<br />

facing the world today” (GS 10).<br />

The knowledge about man derived from divine<br />

revelation does not detract from the rightful autonomy<br />

of man, of society, and of the sciences but rather<br />

52

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

puts it into the proper light: created realities have<br />

their own order and laws; after all, they are the result<br />

of the reason [Vernunft] that the Creator Himself<br />

placed in them (see GS 36). This assessment of the<br />

rightful autonomy of human research and activity<br />

in the sciences, in culture, in business, in the legal<br />

system, in medical advances, and in the service of<br />

politics for the common good of citizens and states<br />

should also allay the suspicion of some political parties<br />

that the Church would use her authority to tip<br />

the scales in the fight for political power. On principle<br />

the Church maintains an equal distance from<br />

political parties that stand on the common ground<br />

of human rights and democracy. Nevertheless she<br />

cannot help intervening constantly on behalf of the<br />

personal dignity of every single human being from<br />

conception until natural death. As she follows Christ,<br />

however, her preferential option for the poor is not<br />

taking sides with any one class or ideology in the fight<br />

for power, but rather participation in the fight for the<br />

non-negotiable dignity and essential equality of all<br />

human beings, regardless of their religion and social<br />

status. A human being must never become a means<br />

53

Benedict and Francis<br />

to an end — this is the necessary “interference” of<br />

the Church in politics.<br />

The Church recalls that in a pluralistic society<br />

there are various competencies in relation to these<br />

earthly realities. But all discussions must remain on<br />

the common ground of the universally binding natural<br />

moral law, which is accessible to human reason<br />

and must not be ignored. The only alternative to<br />

the natural moral law would be the social Darwinist<br />

principle of the survival of the fittest, or “might<br />

makes right” in a battle of everyone for himself. Here<br />

we see clearly the prophetic service that the Church<br />

cannot fail to offer to a pluralistic society and to the<br />

whole human family. This also makes clear, however,<br />

the ethical criterion for the public activity of every<br />

Christian who becomes involved in government,<br />

business, law, culture, and sport for the common good.<br />

For this purpose the Congregation for the Doctrine of<br />

the Faith composed in 2002 a special Doctrinal Note<br />

on Some Questions Regarding the Participation of Catholics<br />

in Political Life. According to this document, all<br />

Christians as citizens of their country are called on to<br />

take part in societal, cultural, and political life. Every<br />

54

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

Christian in a parliament, in a governmental office, or<br />

in the administration and the judiciary has the civil<br />

right and at the same time the personal responsibility,<br />

in conscience before God, to align his political work<br />

with Christian anthropology and Christian teaching<br />

about society and government. The duty of loyalty<br />

and obedience to civil laws and institutions can never<br />

be absolute, inasmuch as a real democracy is already<br />

the alternative plan to state absolutism and totalitarianism.<br />

In his Apostolic Letter Proclaiming Saint<br />

Thomas More Patron of Statesmen and Politicians, John<br />

Paul II observes that this great witness to conscience<br />

did not abandon loyalty to the civil authority and the<br />

legal institutions, yet with his life and death testified<br />

that “man cannot be sundered from God, nor politics<br />

from morality” (AAS 93 [2001]: 78f.).<br />

This is the constructive critical laicity that we<br />

Christians owe to the common good. What we expect<br />

of a state founded on the natural law — according<br />

to the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas about<br />

government and the teaching in Francisco de Vitoria<br />

about international law — is only the theoretical and<br />

practical recognition of the human dignity and the<br />

55

Benedict and Francis<br />

human rights of all, and by no means any compliance<br />

with the doctrines of the Faith that result from<br />

supernatural revelation, which can be accepted only<br />

by free consent anyway.<br />

The Second Vatican Council’s Declaration Dignitatis<br />

humanae is of the utmost importance in defining the<br />

Church’s relation to the nonconfessional, philosophically<br />

neutral state that is founded on the natural law.<br />

In this document the Church affirms “the principle<br />

that religious liberty is in keeping with the dignity<br />

of man and divine revelation” (DH 12). The only<br />

possible foundation of a society is the dignity of man.<br />

He is endowed with it by the Creator. It is part of his<br />

intellectual-moral nature and constitutes the mystery<br />

and the uniqueness of his person. This dignity belongs<br />

to man from the very start, and no power in the world<br />

can deprive him of it. Man is a goal and end in himself<br />

and never a means to an end. His conscience is the<br />

sanctuary in which he is encountered by his Creator,<br />

to whom alone he must ultimately give an accounting,<br />

a sanctuary that must be protected against profanation<br />

and consequently from exploitation [Funktionalisierung].<br />

From this come the rights of associations to<br />

56

What Does Laicity Mean for Christians?<br />

self-determination and to protection from influence<br />

or restriction by the state.<br />

For its part, the exercise of religious freedom is<br />

bound up with the natural moral law and has to respect<br />

the lawful public order and legitimate authority<br />

(see DH 7). No man may be forced to act against his<br />

conscience that is aligned with the natural moral law.<br />

Therefore, it would be a violation of human rights<br />

if a physician were compelled to kill a child in his<br />

mother’s womb or to assist a suicide. Likewise no one<br />

may commit immoral actions or disregard lawful public<br />

order by citing certain traditions of his religion.<br />

Any religiously based destructive violence, in other<br />

words, the brutal violation of fundamental human<br />

rights to life and physical integrity, is a contradiction<br />

in itself. Whether and how a more than merely pragmatic<br />

ethics can be developed in theoretical atheism<br />

remains moot. How a moral action can be required<br />

without acknowledging the unconditional obligatory<br />

character of the good, in other words, on the basis of<br />

convention and consensus alone, is to this day not<br />

clear to me. In the religious act, in contrast, man recognizes<br />

that he is finite and ordered to a transcendent<br />

57

Benedict and Francis<br />

mysterium tremendum et fascinosum [awesome, fascinating<br />

mystery]. However he may understand the mystery<br />

of the absolute, he can never feel entitled to take from<br />

others what he himself has received.<br />

The fact that destructive violence has been committed<br />

in the name of religion does not mean that it<br />