Gallery Guide | The Melancholy Museum

Using over 700 items from the Stanford Family Collections, artist Mark Dion’s exhibition "The Melancholy Museum" explores how Leland Stanford Jr.’s death at age 15 led to the creation of a museum, university, and—by extension—the entire Silicon Valley.

Using over 700 items from the Stanford Family Collections, artist Mark Dion’s exhibition "The Melancholy Museum" explores how Leland Stanford Jr.’s death at age 15 led to the creation of a museum, university, and—by extension—the entire Silicon Valley.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

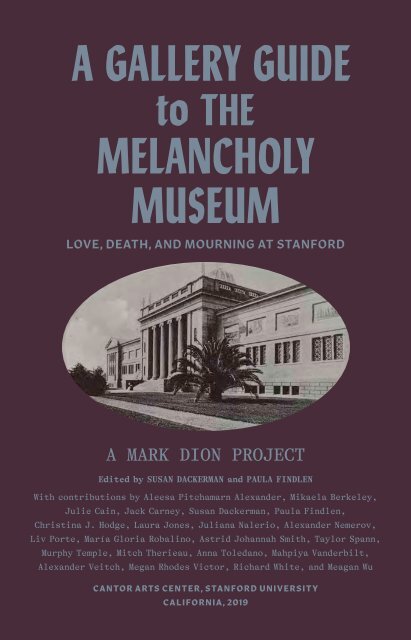

A GALLERY GUIDE<br />

to THE<br />

MELANCHOLY<br />

MUSEUM<br />

LOVE, DEATH, AND MOURNING AT STANFORD<br />

A MARK DION PROJECT<br />

Edited by SUSAN DACKERMAN and PAULA FINDLEN<br />

With contributions by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, Mikaela Berkeley,<br />

Julie Cain, Jack Carney, Susan Dackerman, Paula Findlen,<br />

Christina J. Hodge, Laura Jones, Juliana Nalerio, Alexander Nemerov,<br />

Liv Porte, María Gloria Robalino, Astrid Johannah Smith, Taylor Spann,<br />

Murphy Temple, Mitch <strong>The</strong>rieau, Anna Toledano, Mahpiya Vanderbilt,<br />

Alexander Veitch, Megan Rhodes Victor, Richard White, and Meagan Wu<br />

CANTOR ARTS CENTER, STANFORD UNIVERSITY<br />

CALIFORNIA, 2019

THE MELANCHOLY MUSEUM<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Melancholy</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>: A Mark Dion Project<br />

6 First Inhabitants: <strong>The</strong> Ohlone of the Peninsula<br />

8 Timeline of the Stanfords and <strong>The</strong>ir <strong>Museum</strong><br />

15 <strong>Melancholy</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> Objects<br />

Ohlone Mortar and Pestle; Shovel and Detonator; <strong>The</strong> Last Spike;<br />

Horse Hoof Inkwell; E. E. Rogers, Electioneer; Renaissance Revival<br />

Clock; Watercolor Paint Set; Leland Jr.’s Camera and Photo Album;<br />

Roman Cattle Horns; Alabaster Fruit; I. W. Taber, Leland Jr.’s Nob<br />

Hill <strong>Museum</strong>; Leland Jr.’s Death Mask; Porcelain Cup and Saucer;<br />

Black Ostrich Feather Fan; Banquet Menu; Wage Receipts; Flowerpot;<br />

Salviati Mosaic Workers; Bourbon Bottles; Jane’s Jewelry; Spirit<br />

Photograph; Poison Bottle<br />

26 Leland Stanford Sr. and the Central Pacific Railroad<br />

28 Immigrant Labor on the Stanford Estate<br />

30 <strong>The</strong> Palo Alto Stock Farm<br />

31 Horse Relics<br />

33 Palo Alto Spring: <strong>The</strong> Martyrdom of Time<br />

36 <strong>The</strong> Damkeeper’s Grief<br />

37 A Boy’s Cabinet: Origins of the Leland Stanford<br />

Junior <strong>Museum</strong><br />

40 Spiritual Afterlives<br />

43 Who Killed Jane Stanford?<br />

45 <strong>The</strong> 1906 and 1989 Earthquakes<br />

48 Credits and Acknowledgments<br />

front cover: <strong>Museum</strong>, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California,<br />

c. 1900. Cantor Arts Center<br />

opposite: Leland Jr. Death Mask, 1884. Stanford University Archives

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Melancholy</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>:<br />

A Mark Dion Project<br />

SUSAN DACKERMAN<br />

John and Jill Freidenrich Director, Cantor Arts Center<br />

ALTHOUGH THE MUSEUM ESTABLISHED BY LELAND SR. AND JANE<br />

Stanford in memory of their son, Leland Jr., is celebrating its 125th<br />

anniversary this year, it has only been in active operation for a portion<br />

of that time. In the wake of the fifteen-year-old’s tragic death, his<br />

parents founded both Leland Stanford Junior University and the<br />

Leland Stanford Junior <strong>Museum</strong>, the latter of which opened in 1894<br />

and was expanded in 1900. When it was built, its grandeur and scale<br />

were rivaled only by its East Coast contemporaries—the Metropolitan<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> of Art in New York, Boston’s <strong>Museum</strong> of Fine Arts, and the<br />

Philadelphia <strong>Museum</strong> of Art. Twelve years into its life, however, the<br />

1906 San Francisco earthquake catastrophically toppled the majestic<br />

museum, and much of its collection was lost to the collapse and the<br />

looting that followed. Because Jane Stanford, the museum’s most vocal<br />

advocate, died in 1905, when it reopened in 1909 only a quarter of the<br />

former building was salvaged, and part of that space was given over to<br />

classrooms, laboratories, and storage rather than display. In 1945 the<br />

building closed for further renovations and did not reopen again until<br />

1954. During this time a much-needed inventory of the art collection<br />

was conducted, and much was determined to be lost.<br />

During that half century of the museum’s closure and instability,<br />

most other art museums across the nation were building their<br />

collections and developing their educational missions. Thus, from the<br />

1950s through the 1980s, Stanford’s museum curators and art history<br />

faculty made up for lost time, heroically working to revitalize the<br />

institution into a worthy center for exhibitions, research, and teaching.<br />

But while lightning never strikes twice, earthquakes do, and in 1989<br />

the Loma Prieta quake again critically damaged the building and its<br />

collections. <strong>The</strong> museum’s first century of existence was steeped in<br />

sorrow and destruction.<br />

Gustave-Claude-Etienne Courtois (1852–1923),<br />

Portrait of Leland Stanford Jr., 1884. Cantor Arts Center<br />

3

When the renamed Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts<br />

reopened in 1999, with a new addition on its southwest quadrant, it<br />

included galleries dedicated to the display of objects from the Stanford<br />

family’s original collection. <strong>The</strong> Stanfords’ idea to found a museum<br />

had emerged from their son’s capacious collecting and museological<br />

inclinations. At home he collected and displayed toys, Native American<br />

mortars and pestles, photographs, and taxidermied birds and animals,<br />

to which he added Egyptian and Mediterranean antiquities, relics of<br />

warfare, and other artistic and natural curiosities from his European<br />

travels. After the boy’s death in Florence in 1884, his parents continued<br />

to supplement his collection with objects from around the world—as<br />

he would have done himself had he lived. Born of love and grief,<br />

the collection kept their son’s dream of a museum, as well as his<br />

acquisitive nature, alive.<br />

What happens when a museum is erected to contain all that love<br />

and sorrow? Although Leland Jr.’s death precipitated the founding<br />

of one of the most illustrious universities in the world, which in turn<br />

prompted the emergence of Silicon Valley and globe-changing<br />

technological innovations, his art museum continues to be the site<br />

of his mourning. While the proximate Stanford Mausoleum holds<br />

the eternal remains of father, mother, and son, their ghosts inhabit<br />

the museum. <strong>The</strong>se apparitions take the form of memorial paintings,<br />

mundane objects that Leland Jr. and his parents gathered and held in<br />

their hands, goods of the indigenous people who originally populated<br />

the region, mementos of the Chinese workers who labored for the<br />

Stanfords, as well as artifacts of the family’s businesses, their Palo Alto<br />

home, and their deaths. How can a museum present a collection that<br />

embodies so much history and emotion?<br />

All that grief, love, and mourning have found a new home in<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Melancholy</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>, an installation created by artist Mark Dion.<br />

To house the objects Leland Jr. amassed, and the stuff his parents<br />

accumulated to remember him, Dion has created a mourning cabinet.<br />

<strong>The</strong> grand Victorian case houses the boy collector’s earthly and<br />

otherworldly sepulchral goods as well as his parents’ heartache,<br />

anguish, and hope. Through the past year, Dion has sorted through<br />

the remains of the Stanfords’ lives and dreams. He has examined with<br />

his own collector’s eye young Leland Jr.’s collection and identified<br />

those materials that best tell his and his museum’s story. Assembled<br />

on the cabinet’s shelves and drawers, the stuff narrates the boy’s life<br />

and death through<br />

images and objects<br />

related to the four<br />

elements—earth, air,<br />

fire, and water—and<br />

ether, his final resting<br />

place. Individually<br />

and collectively these<br />

aggregated materials<br />

give Leland Jr. and his<br />

parents an afterlife<br />

within the museum.<br />

Dion also has<br />

excavated other<br />

Stanford histories,<br />

of both family and<br />

place. Digging through<br />

Special Collections<br />

Émile Munier (1840–1895), Leland Stanford Jr. and the Archaeology<br />

as an Angel Comforting His Grieving Mother,<br />

Center, he found<br />

1884. Cantor Arts Center<br />

assorted letters,<br />

ledgers, and objects<br />

to describe the lives and deaths of others whose lives and labor made<br />

possible the university and the museum and its collections. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

causalities and tragedies are also represented in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Melancholy</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong> in the form of fragmented pots, tools, and bodies.<br />

Through objects alone, Dion’s installation tells the story of how<br />

one family’s rush West to sell hardware to prospectors resulted in the<br />

accumulation of vast wealth and power. <strong>The</strong> furniture, photographs,<br />

Native American objects, menus, and other artifacts of material life at<br />

the turn of the twentieth century that comprise the artwork show how<br />

the family upgraded its business interests to politics, the railroad, and<br />

a horse farm, and how those interests were enabled by land previously<br />

inhabited by the Ohlone people and the labor of Chinese and other<br />

immigrants. Finally, the grand Victorian mourning cabinet, the heart<br />

of Dion’s work, demonstrates how one teenage boy’s death resulted<br />

not in the creation of the nation’s largest museum but in a museum<br />

where love, grief, and mourning are forever entwined, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Melancholy</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

4<br />

5

First Inhabitants:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ohlone of the Peninsula<br />

CHRISTINA J. HODGE<br />

Academic Curator and Collections Manager, Archaeology Center, and<br />

LAURA JONES<br />

Director of Heritage Services and University Archaeologist<br />

with contributions by<br />

CHARLENE NJIMEH (Chair) and MONICA ARRELANO (Vice-Chair),<br />

Muwekma Ohlone Tribe<br />

IN THIS PLACE, ON THESE LANDS, TIME STARTS BEFORE MEMORY.<br />

This deep and ongoing story belongs to the Ohlone people and the local<br />

Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area, who explain<br />

that Ohlone people have been here since time immemorial. <strong>The</strong>ir tribe<br />

represents “all the known surviving lineages aboriginal to the San<br />

Francisco Bay region who trace their ancestry through the Missions<br />

Dolores, Mission Santa Clara, and Mission San Jose; and who were<br />

also members of the historic Federally Recognized Verona Band of<br />

Alameda County.” Ohlone ancestral, un-ceded territories comprise<br />

much of the lands surrounding the San Francisco Bay, including those<br />

of Stanford University.<br />

With this declaration, the tribe members constitute themselves<br />

through place and family. <strong>The</strong>se twin anchors held fast through<br />

colonial violence and systematic attempts at eradication that began in<br />

the late eighteenth century. With the tribe’s help, Stanford University<br />

has grown in understanding this history and its own accountability.<br />

Today, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has become one of the institution’s<br />

most important partners.<br />

In the deep past, indigenous Bay Area communities lived in dozens of<br />

distinct villages across a productive landscape, which they understood and<br />

managed. Each group had recognized homelands, but each village was<br />

also multicultural, as young people were required to marry partners from<br />

outside their home villages. Over thousands of years, ancestral Ohlone left<br />

tangible signs across their homelands through artifacts, buried features,<br />

and changes to the land itself. Stanford University cares for many such<br />

sites. Alongside tribal knowledge, archaeological evidence contradicts the<br />

notion that European and US occupiers found a western “wilderness.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>y entered a dynamic world susceptible to violent disruption.<br />

6<br />

In 1769, Spain claimed California lands by sending Catholic missionaries<br />

and invading armies, inaugurating a catastrophic era of compulsory labor,<br />

disease and deprivation, and the imposition of Christianity. <strong>The</strong> Ohlone<br />

were among those forced to labor for Crown and Church in missions,<br />

in presidios, and on Ohlone lands seized and granted by the Crown to<br />

its faithful soldiers. <strong>The</strong> Ohlone people maintained a forceful resistance<br />

against Spanish occupation for decades. Even as their situation grew more<br />

perilous under Mexican and US rule in the nineteenth century, leading<br />

them to eventually hide their Indian identity, language, and customs, they<br />

survived, returning to ancestral lands and forming new communities. <strong>The</strong><br />

largest of these was in Pleasanton in the East Bay hills, where hundreds of<br />

Ohlone and their relatives from neighboring tribes gathered at the Alisal<br />

Rancheria and made a valiant attempt to regain their independence at the<br />

turn of the century. But their land claims were not respected. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

evicted and the village was burned to the ground.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Muwekma Ohlone still struggle today with the consequences<br />

of US colonial policies that ignored their land claims and encouraged<br />

assimilation. <strong>The</strong>ir continuing solidarity and resilience as a community<br />

are remarkable. <strong>The</strong> tribal government continues to advocate for their<br />

rights with local, state, and federal government agencies. While living<br />

fully modern lives in our Bay Area cities, Ohlone people gather and<br />

prepare traditional foods, teach the children their traditions and the<br />

Chochenyo language, and advocate for the preservation of sacred sites.<br />

Stanford’s reeducation about Muwekma history began in the 1980s<br />

with difficult conversations about the return of thousands of ancestral<br />

human remains and funerary objects excavated by Stanford faculty<br />

and stored in the basement of the former Leland Stanford Junior<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> (now the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts).<br />

Stanford repatriated the human remains and funerary objects to the<br />

Ohlone in 1988 for reburial. This history makes the museum a powerful<br />

place in Ohlone memory. Today, the university and tribe are strong<br />

partners in community-led archaeology, historic interpretation, and a<br />

Native plant garden.<br />

Former Muwekma tribal chairwoman Rosemary Cambra stresses<br />

her tribe’s survivance: “Our people, the Muwekmas, the East Bay<br />

families, have never left their lands. <strong>The</strong>y have always been here for<br />

generation after generation.” Today, tribal members remain connected<br />

to their homelands—including Stanford, which has dedicated<br />

residential space for indigenous students known as Muwekma-Tah-<br />

Ruk—<strong>The</strong> House of the People.<br />

7

Timeline of the Stanfords<br />

and <strong>The</strong>ir <strong>Museum</strong><br />

1824 Leland Stanford Sr. is born on<br />

March 9 outside of Troy, New York.<br />

1828 Jane Eliza Lathrop is born in<br />

Albany, New York, on August 25.<br />

1848 Leland Sr. passes the<br />

New York bar exam and opens<br />

a law office in Port Washington,<br />

Wisconsin.<br />

1850 Leland Sr. returns to Albany to<br />

marry Jane on September 30.<br />

1852 After fire destroys his law<br />

office, Leland Sr. travels to California<br />

to join his brothers’ mercantile<br />

business in El Dorado County in<br />

gold country. Jane stays in New York<br />

to tend to her dying father.<br />

1853–55 With his brothers’ financial<br />

support, Leland Sr. operates a<br />

mercantile store with partner Nick<br />

Smith, while his brothers open a<br />

mercantile in Sacramento.<br />

1855 Leland Sr. brings Jane out to<br />

California and buys the Sacramento<br />

mercantile.<br />

1856 Leland Sr. helps found the<br />

California chapter of the Republican<br />

Party.<br />

1861 <strong>The</strong> Big Four—the others are<br />

Collis Potter Huntington, Mark<br />

Hopkins, and Charles Crocker—<br />

form a committee, with Leland Sr.<br />

LIV PORTE<br />

Curatorial Assistant, Cantor Arts Center<br />

as president, to build the Central<br />

Pacific Railroad eastward from<br />

Sacramento.<br />

Leland Sr. is elected governor of<br />

California.<br />

1863 Leland Sr. breaks ground on<br />

the new railroad. <strong>The</strong> “Governor<br />

Stanford” locomotive is built<br />

in Philadelphia and Lancaster,<br />

Pennsylvania, and shipped around<br />

Cape Horn to San Francisco.<br />

It makes its first run in November.<br />

1865–68 Leland Sr. hires several<br />

thousand Chinese men to help<br />

build the transcontinental railroad.<br />

An additional group of Chinese<br />

laborers will work at the family’s<br />

private residences in San Francisco,<br />

Sacramento, Palo Alto, and<br />

Washington, DC, until his death in<br />

1893.<br />

1867 After a farewell tea party, Jane<br />

begins several months of secluded<br />

rest, per doctor’s orders, to prepare<br />

for childbirth.<br />

1868 Leland DeWitt Stanford Jr.<br />

is born on May 14. His parents<br />

allegedly announce his arrival at<br />

a dinner party by presenting him<br />

nestled in a bed of blossoms on a<br />

silver platter.<br />

1869 <strong>The</strong> driving of the Golden<br />

Spike on May 10 commemorates the<br />

completion of the transcontinental<br />

railroad.<br />

Leland Sr. purchases his first racing<br />

trotter, Occident.<br />

1872 Leland Sr. meets the<br />

naturalist Louis Agassiz in<br />

Sacramento in October. Agassiz<br />

encourages the founding of<br />

institutions of learning on the West<br />

Coast, including museums of natural<br />

history and art.<br />

Leland Sr. commissions famed<br />

photographer Eadweard Muybridge<br />

to photograph his horses in motion.<br />

1874 After nineteen years in<br />

Sacramento, the Stanford family<br />

moves its primary residence to<br />

San Francisco.<br />

1876 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords move into their<br />

Nob Hill mansion and purchase the<br />

Palo Alto estate as a country home.<br />

Leland Sr. purchases a second<br />

horse, Electioneer, for $12,000,<br />

along with twelve mares costing<br />

an additional $29,200, planning<br />

to breed world-record-breaking<br />

trotters.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stanfords travel to the<br />

Philadelphia Centennial Exposition,<br />

where they display two Thomas<br />

Hill paintings, Donner Lake and<br />

Yosemite Valley. Hill wins a medal<br />

for landscape painting.<br />

1877–78 Leland Sr. commissions<br />

Eadweard Muybridge to photograph<br />

the completed Nob Hill mansion,<br />

known as “millionaire’s mansion.”<br />

1879 <strong>The</strong> Stanford family purchases<br />

twelve hundred trees and shrubs<br />

from an establishment in Flushing,<br />

8<br />

9

New York, and transports them<br />

to their Palo Alto estate via the<br />

transcontinental railroad.<br />

1880 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords take Leland<br />

Jr. on a two-year trip to Europe.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y acquire family portraits in<br />

Paris, sculptures in Rome, and early<br />

modern paintings in Florence.<br />

Chinese gardeners begin to lay out<br />

the Palo Alto arboretum.<br />

1881 While in Pompeii in March<br />

1881, Jane allegedly advises Leland<br />

Jr. to make a piece of broken Roman<br />

mosaic glass the foundation of his<br />

future museum.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stanfords purchase land near<br />

Vina, California, planting more<br />

than one million grapevines and<br />

employing around three hundred<br />

mostly Chinese laborers.<br />

1882 <strong>The</strong> Catalogue of Leland<br />

Stanford’s Collection of Pictures,<br />

listing 181 paintings in the Nob Hill<br />

mansion, is printed.<br />

Leland Jr. dreams of making his<br />

burgeoning collection the nucleus<br />

of a great West Coast museum. He<br />

arranges a room of his treasures<br />

on the third floor of the Nob Hill<br />

mansion.<br />

1883 French vintners improve the<br />

quality of Vina Ranch wine, though it<br />

is more successful with brandy and<br />

sweet wine than dry French wine.<br />

1884 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords embark on<br />

a second trip through Europe.<br />

Leland Jr. collects everywhere they<br />

go. In Naples he begins showing<br />

signs of illness, later diagnosed as<br />

typhoid fever, probably contracted in<br />

Constantinople en route to Athens.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stanfords call in the best<br />

doctors in Rome, then take him to<br />

Florence. Leland Jr. dies in the Hotel<br />

Bristol in Florence on March 13,<br />

aged fifteen years and ten months.<br />

Awaiting the completion of their<br />

Palo Alto mausoleum, the Stanfords<br />

travel with Leland Jr.’s body to Paris<br />

and New York. <strong>The</strong>y acquire five<br />

thousand duplicates of Cypriote<br />

antiquities from the Cesnola<br />

Collection at the Metropolitan<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> of Art.<br />

<strong>The</strong> family buries their son in Palo<br />

Alto on November 27. A public<br />

service takes place in Grace<br />

Cathedral in San Francisco on<br />

November 30.<br />

1885 On November 11, Leland Sr.<br />

and Jane file for a grant to establish<br />

a university in honor of their son.<br />

Leland Sr. is elected to serve as a<br />

US senator from California.<br />

1886 Leland Jr.’s former tutor<br />

Herbert Charles Nash publishes <strong>The</strong><br />

Leland Stanford, Jr. <strong>Museum</strong>: Origin<br />

and Description, describing the<br />

current state of the collection.<br />

1887 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords contemplate<br />

San Francisco’s Twin Peaks as the<br />

site for their future museum, after<br />

deciding against Golden Gate Park.<br />

Jane sets a cornerstone marking<br />

the edge of the future university on<br />

May 14.<br />

1888 Jane and Leland Sr. embark<br />

upon their first trip to Europe<br />

following Leland Jr.’s death, amid<br />

rumors that Leland Sr. will become<br />

the Republican presidential<br />

candidate.<br />

1890 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords finalize their<br />

decision to build a museum on their<br />

Palo Alto land.<br />

<strong>The</strong> approximately two hundred<br />

laborers at Vina Ranch, whose<br />

numbers swell to around one<br />

thousand at harvest, are now mostly<br />

European immigrants or white US<br />

Americans because of growing anti-<br />

Chinese sentiment.<br />

<strong>The</strong> racehorse Electioneer dies on<br />

December 3.<br />

Leland Sr. steps down as president<br />

of the Central Pacific Railroad<br />

and is elected to a second term<br />

as senator.<br />

1891 Jane and Leland Sr. establish<br />

the Leland Stanford Junior <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

Ground is broken on February 18.<br />

Breeder and Sportsman reports on<br />

June 27 that Electioneer’s skeleton<br />

is “mounted and ready to be placed<br />

in the museum at Palo Alto.”<br />

Occident’s skeleton has been in<br />

Stanford’s stable since 1886. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

are now approximately 750 Stock<br />

Farm horses.<br />

Stanford University opens its doors<br />

in October to five hundred students,<br />

and hires Chinese cooks to feed<br />

them.<br />

Newspapers report that Jane “blazed<br />

with diamonds” at a Washington, DC,<br />

party.<br />

1892 <strong>The</strong> Stanfords make their<br />

last trip to Europe together. In an<br />

interview, Jane declares her intent<br />

to make their museum “the finest<br />

art gallery that any school or college<br />

possesses.”<br />

1893 Leland Sr. dies on June 21<br />

and is buried on June 25. Jane<br />

burns their correspondence and<br />

becomes the Stanford estate’s sole<br />

trustee. She transfers works of<br />

art from San Francisco to Palo Alto<br />

in August.<br />

10<br />

11

Timothy Hopkins, son of Mark<br />

Hopkins, and his wife, May, give<br />

the museum Reverend Henry G.<br />

Appenzeller’s collection of Korean<br />

artifacts.<br />

Jane bequeaths the Stanford<br />

family mansion in Sacramento to<br />

the Roman Catholic Church as a<br />

home for orphaned children. <strong>The</strong><br />

family home in Albany becomes<br />

the Lathrop Memorial, a home for<br />

orphans supervised by the Albany<br />

Orphan Society.<br />

Jane approves Maurizio Camerino’s<br />

designs for mosaic panels of<br />

History and Ancient Art, but finds<br />

the Salviati & Co. director’s image<br />

of Modern Art better suited to “a<br />

botanical collection, but not for an<br />

Art <strong>Museum</strong>,” preferring instead an<br />

image of ancient Abyssinia.<br />

Jane purchases Henry Chapman<br />

Ford’s twenty-four watercolors of the<br />

California missions. <strong>The</strong>y become<br />

part of the museum’s collection<br />

related to the missions and early<br />

California history.<br />

Jane announces to the board of<br />

trustees on February 11 that she has<br />

deeded her San Francisco home to<br />

the university.<br />

1899 <strong>The</strong> first shipment of art and<br />

antiquities from the Stanfords’<br />

Washington, DC, mansion arrives<br />

on July 3, along with David Starr<br />

Jordan’s gift of seal furs and a<br />

stuffed panther.<br />

Jane purchases John Daggett’s<br />

collection of Native American curios,<br />

especially baskets from the Yurok,<br />

Karok, and Hupa tribes near the<br />

Klamath River, which have been on<br />

loan to the museum since 1893.<br />

Jane travels to Europe in the<br />

summer and fall.<br />

1900 Two new brick wings of the<br />

museum are completed, making<br />

it one of the largest in the world<br />

at three hundred thousand square<br />

feet. Jane’s elaborate directions<br />

regarding how the inscription on<br />

the facade should commemorate<br />

her son are ignored. Harry Peterson<br />

becomes the first director, holding<br />

this position until 1917.<br />

1900–1901 Jane travels to Europe<br />

and Egypt and collects antiquities<br />

for the museum.<br />

1903 <strong>The</strong> Palo Alto Stock Farm<br />

closes and the horses are sold.<br />

Assistant curator E. A. Austin ’05<br />

collects minerals above Sutter Creek<br />

to build the museum’s mineralogical<br />

collection.<br />

Salviati & Co. donates two hundred<br />

pieces of Venetian glass, followed by<br />

a gift of an additional eighty items<br />

in 1904, for the museum’s Venetian<br />

Room.<br />

1894 <strong>The</strong> Leland Stanford Junior<br />

<strong>Museum</strong> opens its doors in the fall.<br />

John Milton Oskison, a young Anglo-<br />

Cherokee student, recalls being told<br />

around this time that the museum<br />

possessed a replica of Leland Jr.’s<br />

last breakfast.<br />

1897 Jane fails to sell her jewels<br />

in London during Queen Victoria’s<br />

Diamond Jubilee, but is still<br />

determined to sacrifice them to<br />

support the university. She has them<br />

photographed and painted in oils.<br />

After admitting San Mateo<br />

teachers to the museum gratis and<br />

expressing willingness to extend the<br />

same courtesy to “all invitees and<br />

distinguished visitors,” Jane denies<br />

David Starr Jordan’s proposal to<br />

admit all visitors free, claiming that<br />

“there would be no discipline, order,<br />

or restriction after a few years of<br />

such freedom.”<br />

Jane’s brother, Henry Lathrop, dies<br />

on April 3. Jane commissions a<br />

sculpture in his honor, <strong>The</strong> Angel of<br />

Grief, and has it placed next to the<br />

family mausoleum.<br />

1902 Jane travels to Hawaii, Japan,<br />

and other parts of Asia to collect<br />

Asian artifacts. By then Hill’s Donner<br />

Lake and Yosemite Valley are on<br />

display. She considers the museum<br />

“necessary and appropriate to a<br />

university of high degree.”<br />

Jane hands over control of university<br />

affairs to the board of trustees.<br />

En route to Japan and other parts<br />

of Asia she visits her brother-inlaw<br />

Thomas Welton Stanford in<br />

Australia.<br />

1904 Jane attends the St. Louis<br />

Exposition and purchases the Ikeda<br />

collection of Japanese and Chinese<br />

art. She justifies the cost of the<br />

12<br />

13

museum expansion, reminding<br />

everyone that all her collectibles<br />

will end up there upon her death:<br />

“<strong>The</strong>se things that have been placed<br />

in the <strong>Museum</strong> by myself are never<br />

to be moved.” She chairs the newly<br />

formed Committee on the <strong>Museum</strong>.<br />

1905 In January, rat poison is<br />

found in a bottle of water on Jane’s<br />

nightstand. On February 28, Jane<br />

dies in her room at the Moana Hotel<br />

in Honolulu. <strong>The</strong> coroner declares<br />

strychnine poisoning the cause. A<br />

murder investigation begins March 1.<br />

Harry Peterson celebrates Jane’s<br />

fifty years of lace collecting with a<br />

feature article in the Ladies’ Home<br />

Journal.<br />

14<br />

1906 On April 18, three-quarters<br />

of the museum building is<br />

destroyed during San Francisco’s<br />

great earthquake. Over some<br />

months, Harry Peterson salvages,<br />

reorganizes, and inventories what is<br />

left of the collection.<br />

TIMELINE IMAGE CAPTIONS<br />

1863: Governor Stanford Locomotive Entering Stanford <strong>Museum</strong>, 1916.<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

1868: Portrait of Leland Stanford Jr. as an Infant, Original Carte de<br />

Visite in Leland Stanford Photograph Album, n.d. Stanford University<br />

Archives<br />

1877–78: Photograph of the Art <strong>Gallery</strong> in the Stanford Family’s Nob Hill<br />

Mansion, SF, Stanford Residence (San Francisco) Photograph Album, Picture<br />

<strong>Gallery</strong>, n.d. Stanford University Archives<br />

1881: Three Laborers Standing Outside the 1906 Earthquake Damage to<br />

Exterior of the Leland Stanford Jr. <strong>Museum</strong>, c. 1906. Cantor Arts Center<br />

1884: Display of the Cesnola Collection at the Leland Stanford Jr. <strong>Museum</strong><br />

after the 1906 Earthquake, 1906. Cantor Arts Center<br />

1893: A Partial View of Ten Panel Folding Screen (ch’aekkori), c. 1890.<br />

Cantor Arts Center; California Missions: San José de Guadalupe, 19th<br />

century. Cantor Arts Center<br />

1897: Mrs. Stanford’s Jewel Collection, 1898. Cantor Arts Center<br />

1900–1901: Photograph of Mrs. Leland Stanford and Party Taken at Gizeh,<br />

near Cairo on Jan 1, 1904, 1904. Stanford University Archives<br />

1903: A Table of Recovered and Damaged Salviati Glass after the 1906<br />

Earthquake, 1906. Stanford University Archives<br />

1906: Two Figures, One Wearing Asian Armor, Outside of the Leland<br />

Stanford Jr. <strong>Museum</strong> after the 1906 Earthquake, early 20th century.<br />

Cantor Arts Center<br />

MELANCHOLY MUSEUM OBJECTS<br />

OHLONE MORTAR AND PESTLE<br />

Stanford University Archaeology Collections<br />

Leland Stanford Jr. was captivated<br />

by ancient cultures of<br />

Europe and Africa, but he<br />

grounded his museum—literally—in<br />

the local. A photograph<br />

of his nascent collection shows<br />

bowl-like mortars and long pestles<br />

arranged on a floor. Used to<br />

grind everything from spices<br />

and nuts to medicines and meat,<br />

the mortar and pestle was part of the essential tool kit for many cultures,<br />

including the Muwekma Ohlone who originally inhabited the Bay Area and<br />

continue to live here today. Jane Stanford took pains to attribute the discovery<br />

of these artifacts to her son, writing on a surviving label: “[A]ll these Pestles<br />

and Mortars [were] collected by Leland Stanford [Jr. him]self. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

all plowed [an]d dug up on the Palo [Alto] Ranch.” From the boy’s tutor, we<br />

know the child “would scour the farm” and “spend the day in the fields among<br />

the laborers” collecting what ancestral Ohlone women left behind, such as<br />

this stone set made between 6000 BCE and 1800 CE. Because stone tools<br />

were heavy to carry, they often were cached at seasonal sites to await the<br />

community’s return—or, in this case, to be uncovered centuries later by laborers<br />

and an acquisitive boy.<br />

Megan Rhodes Victor, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Archaeology<br />

SHOVEL AND DETONATOR<br />

Oakland <strong>Museum</strong> of California<br />

In 1848, gold nuggets were found<br />

unexpectedly in a stream near<br />

Coloma, California. Despite efforts<br />

to maintain secrecy, the discovery<br />

captured the attention of three hundred<br />

thousand eager fortune seekers,<br />

who used tools like this shovel<br />

and detonator to search for the<br />

precious metal. Leland Stanford Sr.<br />

sought to exploit the business opportunities engendered by the Gold Rush by<br />

selling such equipment to miners, starting in late 1852 or early 1853. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

tools also helped build the Central Pacific Railroad that he cofounded with his<br />

15

Sacramento business partners. <strong>The</strong> influx of multiethnic European Americans,<br />

Chinese, and South American migrant laborers as well as free and enslaved<br />

Black Southerners who traveled to participate in the Gold Rush drastically<br />

changed California’s demographics. At the same time, the local Native Americans<br />

who were the land’s original inhabitants were starved, displaced, and<br />

murdered. <strong>The</strong> opportunities and tragedies of the Gold Rush and the industries<br />

it spawned invigorated California’s economy, making statehood possible in the<br />

Compromise of 1850, which allowed California to enter the Union and raised<br />

pertinent questions regarding the slave industry across the country.<br />

Liv Porte, Curatorial Assistant, Cantor Arts Center<br />

THE LAST SPIKE<br />

Cantor Arts Center, gift of David Hewes<br />

<strong>The</strong> “last spike” has a way of multiplying. <strong>The</strong> golden railroad spike that<br />

Leland Stanford Sr. drove at Promontory, Utah, in 1869, symbolically uniting<br />

the Union Pacific and Central Pacific into one transcontinental railroad, is at<br />

the Cantor. But there is also the ordinary iron spike that replaced it at the end of<br />

the ceremony, which Union Pacific fireman David Lemon promptly pocketed<br />

as a memento. To add intrigue, the Stanford Golden Spike has an identical<br />

twin, secretly commissioned<br />

and kept in<br />

obscurity by businessman<br />

David Hewes, who<br />

ensured that the telegraph<br />

instantaneously<br />

conveyed the joining of<br />

the two railroad lines.<br />

And to make counting<br />

all but impossible, an uncertain number of miniature spikes have been made<br />

from excess bits of the gold from the Stanford original; Hewes distributed<br />

them as gifts to friends and family. All are equally historical relics and tourist<br />

souvenirs, each imbued with some degree of authenticity from this transformative<br />

moment in the history of the West.<br />

Mitch <strong>The</strong>rieau, PhD candidate, Modern Thought and Literature<br />

HORSE HOOF INKWELL<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

This lavishly decorated silver inkwell set within a horse’s hoof, made circa<br />

1878, commemorates a stallion with a muddled history. In recollections of his<br />

childhood published in 1945 by his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, President Franklin<br />

Delano Roosevelt fondly recalled Gloster as his father’s record-breaking<br />

trotter, sold to Leland Stanford Sr. for $15,000 in 1873. One story goes that<br />

Gloster died in a train wreck while being shipped to California in spring<br />

1874, and a stable hand removed and mounted his tail and, many years later,<br />

16<br />

presented it in 1930 to Roosevelt, who<br />

hung it in the governor’s mansion and<br />

subsequently his White House bedroom<br />

as a memento of his Hudson<br />

Valley boyhood. In reality, Roosevelt’s<br />

father, James, sold Gloster to another<br />

New York horse breeder, Alden Goldsmith,<br />

who sent the horse out West<br />

to race against Stanford’s prize horse<br />

Occident. Gloster died of lung fever<br />

in San Francisco on October 30, 1874,<br />

after a private contest but before the<br />

public race. <strong>The</strong>reafter, the Golden<br />

Gate Agricultural Association had one of Gloster’s hooves mounted and<br />

adorned with precious Western metals. But they neglected to pay the jeweler,<br />

and so the jeweler sold the item to a Richard T. Carroll in 1879, who in turn<br />

returned it to Goldsmith. How or when Leland Sr. acquired it, or whether this<br />

is a different hoof, similarly mounted, remains unknown.<br />

Mikaela Berkeley, Stanford ’20 and Paula Findlen, Ubaldo Pierotti<br />

Professor of Italian History<br />

E. E. ROGERS, ELECTIONEER<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

A dark bay horse with white pasterns on the hind legs, measuring about 15.2<br />

hands (roughly five feet) tall at the withers, Electioneer (1868–1890) was a pillar<br />

of Leland Stanford Sr.’s Palo Alto Stock Farm. Stanford purchased the virtually<br />

untested Electioneer for $12,000 in 1876. <strong>The</strong> horse, described by trainer<br />

Charles Marvin as “the perfection of driving power,” became foundational to<br />

the growth of the Stock Farm. Using Electioneer purely as a stud horse, Stanford<br />

experimented with different breeding and training techniques to produce<br />

the world’s fastest trotters. As a result of the “Palo Alto system,” even today<br />

Electioneer’s descendants hold virtually all trotting and pacing speed records.<br />

<strong>The</strong> little-known artist E. E. Rogers created this somewhat inaccurate painting<br />

of Electioneer in 1889. <strong>The</strong><br />

actual horse did not have spots<br />

on his shoulder, and his hooves<br />

were all the same color. Most<br />

likely these mischaracterizations<br />

resulted from the painting<br />

being based on an imperfect<br />

photograph.<br />

Mahpiya Vanderbilt, Stanford<br />

’19 and Alexander Veitch,<br />

Stanford ’19<br />

17

RENAISSANCE REVIVAL CLOCK<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stanford family’s Renaissance Revival clock<br />

was made in France around 1876. While sold by<br />

Tiffany & Co., such a fine, elegant piece was<br />

likely the work of multiple individuals, with the<br />

maker controlling the overall quality. In 1876,<br />

Tiffany & Co. made a dramatic impression on<br />

Victorian crowds with a dazzling display of jewels<br />

and silver goods at the Centennial Exposition<br />

in Philadelphia, where Leland Stanford Sr.<br />

bought Jane an exquisite Tiffany diamond necklace<br />

and earrings for their tenth wedding anniversary.<br />

This massive clock sat atop the mantel<br />

of the receiving room, or India Room, in the Stanford family’s palatial Nob Hill<br />

home, flanked by a pair of decorative urns and electric candelabras. In furnishings<br />

as in jewelry, every object and decorative embellishment in any one<br />

of the mansion’s fifty rooms was carefully arranged to represent the perfect<br />

mix of antique and modern treasures of the finest quality. Like so many other<br />

San Francisco residences, the Stanford mansion was lost in the 1906 earthquake,<br />

but the clock remains.<br />

Astrid Johannah Smith, Rare Book and Special Collections Digitization<br />

Specialist and Stanford MLA candidate<br />

WATERCOLOR PAINT SET<br />

Cantor Arts Center,<br />

Stanford Family Collections<br />

This late nineteenth-century paint<br />

set is composed of thirty different<br />

color cakes, four ceramic holders,<br />

and two small paintbrushes.<br />

Housed in a Victorian wooden box,<br />

it bears the logo of the London<br />

company Winsor & Newton. This<br />

set of “school colors” was most likely used by Leland Stanford Jr. when he<br />

was learning to paint, perhaps during the summer of 1876 in White Harbor,<br />

Maine, when he sketched the various ships on the water. Commercial in origin,<br />

the color cakes were most likely fabricated industrially and therefore are<br />

smooth and consistent. Watercolors are known for the ethereal, atmospheric<br />

tones they can achieve, mostly through the layering of translucent washes of<br />

diluted pigment. This particular paint set is a fitting palimpsest for the short<br />

life of Leland Jr., whose death suspended an atmosphere of grief over his<br />

household as well as the museum and university built in his honor.<br />

María Gloria Robalino, PhD candidate, Comparative Literature<br />

18<br />

LELAND JR.’S CAMERA<br />

AND PHOTO ALBUM<br />

Cantor Arts Center,<br />

Stanford Family Collections<br />

Around 1880, Leland Stanford Jr.<br />

acquired a device of technological<br />

wonder to record his travels and other<br />

interests. <strong>The</strong> Stanford family had for<br />

years been acquainted with Eadweard<br />

Muybridge, who is well known for his 1877–78 experimental images of the<br />

Stanford horses in motion. <strong>The</strong> famed photographer’s presence at the Stock<br />

Farm and Nob Hill mansion no doubt inspired young Leland’s interest in the<br />

relatively new medium. <strong>The</strong> boy’s own camera was a cutting-edge marvel<br />

comprised of a wooden frame and accordion body that allowed its user to<br />

regulate the distance between the lens and interior glass negative, producing<br />

greater clarity and depth of field than earlier models. Leland Jr.’s photographs<br />

express the creativity and whimsical qualities typical of a young man exploring<br />

the world. Mounted on the lined pages of notebooks, the inexpertly processed<br />

photographs depict such subjects as the Nob Hill mansion, architectural elements<br />

of a French cathedral, foreigners he encountered while touring Europe,<br />

and a dog. <strong>The</strong> front cover of his 1880–81 Cahier de Photographies à Leland<br />

Stanford (Book of Photographs by Leland Stanford) is decorated with a charming<br />

drawing of a young boy composing a photograph under the camera’s cover.<br />

Taylor Spann, Stanford ’21 and Susan Dackerman, John and Jill Freidenrich<br />

Director, Cantor Arts Center<br />

ROMAN CATTLE HORNS<br />

Cantor Arts Center,<br />

Stanford Family Collections<br />

<strong>The</strong>se horns are from a mature chianina bull, an<br />

Italian cattle breed famous for its immense size<br />

and stark white coloring. Its muscular frame and<br />

classical origins probably satisfied the Stanfords’ desire for grandeur and<br />

interest in Roman antiquity. When the family toured Europe in the 1880s,<br />

they might have seen the chianina performing the role of a draft animal,<br />

assisting the peasants who still endured a medieval sharecropping system.<br />

Not only are the horns a piece of natural history, their high polish gives them<br />

an artistic quality. <strong>The</strong>y also may have appealed to the Stanfords as a symbol<br />

of the burgeoning agricultural potential of the West: the Central Pacific<br />

Railroad transported cattle hundreds of miles from the West and Texas to<br />

butchers in the industrial cities of the Midwest and East. Thus, the horns are<br />

both resonant of the rugged and awe-inspiring qualities of California, and<br />

also have deep connections to the Old World and Victorian ideas of culture.<br />

Jack Carney, Stanford ’21<br />

19

ALABASTER FRUIT<br />

Cantor Arts Center,<br />

Stanford Family Collections<br />

During Leland Stanford Jr.’s first trip to<br />

Europe in 1880–81 he acquired some alabaster<br />

fruit, perhaps in Nice. In the nineteenth<br />

century, alabaster—an easy-to-carve, translucent gypsum that absorbs<br />

color well—became a preferred medium for reproducing small antiquities and<br />

architectural forms. Artisans could readily mimic the dull hue and fuzzy texture<br />

of a peach, the brightly dappled skin of citrus, or the yellow-red sheen of<br />

French apples. Carved bits of wood simulated the stems. It made great Victorian<br />

food art, and the markets were flooded with alabaster souvenirs, even<br />

though the prestige of the form was waning by the time the Stanfords were<br />

traveling. Early visitors to the Nob Hill mansion described the fruit as sitting on<br />

a marble platter, possibly arranged with other fake food, in Leland Jr.’s designed<br />

display. After his death it became part of the museum’s collection, leading to<br />

jokes about why Leland Jr.’s last breakfast was on exhibit.<br />

Paula Findlen<br />

I. W. TABER, LELAND JR.’S NOB HILL MUSEUM<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

After Leland Stanford Jr. died in 1884, his mother, Jane Stanford, commissioned<br />

photographs of her son’s burgeoning museum, then located on the top floor of<br />

their Nob Hill mansion. <strong>The</strong> images document not only Leland Jr.’s vast collection<br />

of arms and armor, stuffed birds, antiquities, and other curios, but also<br />

his fastidious curatorial decisions. <strong>The</strong> collection eventually made the journey<br />

from San Francisco to Palo Alto to take its rightful place in the Leland Stanford<br />

Junior <strong>Museum</strong>, and the photographs provided a template for the new galleries<br />

dedicated to the boy’s museological vision. Much as the Palo Alto Stock Farm<br />

was transformed into a site of public education, Leland Jr.’s collection evolved<br />

from a private cabinet into a fullfledged<br />

public museum. Today, the<br />

static photograph serves as a death<br />

mask of sorts for this personal collection,<br />

an indexical representation of a<br />

child’s cabinet of wonders.<br />

Anna Toledano, PhD candidate,<br />

History of Science<br />

LELAND JR.’S DEATH MASK<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

This death mask captures the visage of Leland Stanford Jr. on March 13,<br />

1884, upon his passing at the Hotel Bristol in Florence. Created just after<br />

the fifteen-year-old boy succumbed to typhoid fever while traveling with<br />

20<br />

his parents on their second European trip, it<br />

nonetheless seems like a sleeping portrait of a<br />

beloved child. <strong>The</strong> softness of the lips and chalky<br />

whiteness of the plaster create an eerie youthfulness<br />

that affirms the very idea of the death<br />

mask as a memento of mortality. Because the<br />

cast of the face is a literal imprint of its model,<br />

it captures an uncanny degree of detail: delicate<br />

wrinkles around the eyes, individual hairs of the<br />

brows and lashes, even the slightest protrusion<br />

of a forehead vein. This realism is what makes the death mask so haunting,<br />

reminding us of the lasting presence of a boy whose life ended too soon.<br />

Meagan Wu, MA in Art History ’19<br />

PORCELAIN CUP AND SAUCER<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

This nineteenth-century cup and saucer<br />

were most likely part of a dinner service<br />

belonging to the Stanford family. Made of<br />

porcelain and covered in a shiny black<br />

glaze, their style is opulently art nouveau.<br />

<strong>The</strong> intricate gilt pattern on the lip of the<br />

cup and edge of the plate, and the black<br />

and gold colors, are likewise characteristic<br />

of the style. <strong>The</strong>ir excellent condition suggests that they were part of the<br />

special dinner service for the funeral of Leland Stanford Jr. in 1884, or for<br />

mourning occasions in general. Were they purchased by Jane and Leland Sr.<br />

after their son’s death? Because of their funereal character, it is also possible<br />

that this cup and saucer belonged to an afternoon tea set that Jane used after<br />

her husband and son were entombed in the Stanford Mausoleum in 1893.<br />

María Gloria Robalino<br />

BLACK OSTRICH FEATHER FAN<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

A cursive monogrammed S marks the verso of this fan as a Stanford family<br />

possession. <strong>The</strong> twirling, textured black ostrich plumes and incandescent<br />

mother-of-pearl ribs suggest a combination of delicacy and strength that well<br />

defined Jane Stanford. During her extensive travels she<br />

collected hundreds of fans that accompanied her at<br />

social functions and became part of her elaborate<br />

wardrobe (but most of the others are missing<br />

the Stanford monogram). Such an accessory<br />

suggests opulence, excess, and decadence, and<br />

the fan itself something of feminine affectation.<br />

21

In the hands of such a woman, of course, fanning would have been a feigned<br />

delicacy that dissimulated her power. While Jane often deferred to her husband<br />

publicly, she was the matriarch who, after the death of her son in 1884,<br />

took charge of the creation of a museum in Leland Stanford Jr.’s memory.<br />

After her husband’s death in 1893, she controlled the university as well.<br />

Juliana Nalerio, PhD candidate, Modern Thought and Literature<br />

BANQUET MENU<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

Celebratory banquets in the Gilded<br />

Age were extravagant but frequent<br />

affairs for members of high society.<br />

This banquet, held in honor of<br />

Leland Stanford Sr. and Republican<br />

representatives of Congress elect,<br />

took place at the Palace Hotel in<br />

San Francisco on November 21,<br />

1888. In typical period fashion, the<br />

meal consisted of multiple courses,<br />

each highlighting luxurious or sought- after ingredients such as oysters,<br />

turtle, foie gras, and capon. Diners would take a beverage break during the<br />

middle of the feast, pausing to imbibe punch, a rum-based drink served at<br />

ceremonial events. <strong>The</strong> surfeit of food and alcohol offered at these gatherings<br />

reinforced the social positions of all in attendance, both demonstrating the<br />

host’s ability to source and provide such a lavish affair, and allowing guests<br />

to be waited upon by extremely attentive staff. As the meals might last up<br />

to five hours, these events of purported leisure often ironically turned into<br />

drawn-out performances of conspicuous consumption.<br />

Aleesa Pitcharman Alexander, Assistant Curator of American Art,<br />

Cantor Arts Center<br />

WAGE RECEIPTS<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stanfords hired both a permanent and<br />

a seasonal labor force to maintain their<br />

eight-thousand-acre Palo Alto estate. Wages were disbursed monthly, on Saturday<br />

mornings at the pay table, in the form of gold and silver coins. Workers<br />

preferred coins, as most people did not bank their earnings and had to pay a fee<br />

to get a check cashed. <strong>The</strong>y signed receipts indicating amounts received. Head<br />

horse trainer Charles Marvin earned $250 per month, while cook Ah Joe and<br />

China Boss of Garden and Grounds Ah Jim earned $50 per month. In the 1880s<br />

the average estate worker at Palo Alto earned anywhere from $1 to $1.33 per day,<br />

working seven days per week, twelve hours per day. To defray payroll and other<br />

costs of running the university, Leland Stanford Sr. routinely wrote checks out of<br />

22<br />

his personal funds. After Leland Stanford Sr.’s death in 1893 there was a massive<br />

layoff of estate workers, and the remaining estate and university employees took<br />

a steep pay cut that persisted for another seven years.<br />

Julie Cain, Historic Preservation Planner at Stanford University<br />

FLOWERPOT<br />

Stanford University Archaeology Collections<br />

This terra-cotta flowerpot, recovered as fragments<br />

from the site of the Stanford mansion in Palo Alto,<br />

may appear plain at first glance, but this unremarkable<br />

pot actually speaks to the presence of the bright<br />

array of flowers grown at the Stanford Stock Farm<br />

and, later, on the grounds of the university. Just as a flowerpot indicates the<br />

presence of flower gardens, it also signals the presence of gardeners. Many<br />

of the laborers, including gardeners, who worked at the Stock Farm and the<br />

university during this period were Chinese, and some may have lived in the<br />

Arboretum Chinese Labor Quarters, which was active from the early 1880s<br />

until 1925. <strong>The</strong>se gardeners worked to shape the landscape of Stanford University<br />

as it appears today. All of the now-iconic palms on Palm Drive were<br />

planted by Chinese workers, who also dug and planted the Oval and likely<br />

planted the gardens and orchards that adorn the Main Quadrangle.<br />

Megan Rhodes Victor<br />

SALVIATI MOSAIC WORKERS<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford <strong>Museum</strong> Collections<br />

This 1902 photograph captures artisans at work in the Venice studio of Salviati<br />

& Co. preparing materials for Stanford Memorial Church’s glass mosaic<br />

program. Jane Stanford had long admired the glittering Byzantine mosaics<br />

of Constantinople and Venice, cities she visited with her husband and son in<br />

the 1880s. After their deaths, she sought to memorialize them in grandiose<br />

fashion, and chose the medium of mosaic to adorn the interior and the facade<br />

of the church as well as the exterior of the Leland Stanford Junior <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

which is decorated with scenes related to Leland Jr.’s interests. Jane already<br />

had a long-standing relationship with the Salviati firm when she commissioned<br />

this massive project. Her interest in mosaics and glasswork was also<br />

in keeping with period tastes. During the<br />

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,<br />

Venice was a top tourist destination<br />

for American elites, which stimulated<br />

the Venetian glass revival; the glass was<br />

brought across the Atlantic and sold at luxury<br />

stores like Tiffany and Co., fueling market<br />

and institutional interest in such goods.<br />

Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander<br />

23

BOURBON BOTTLES<br />

Stanford University Archaeology Collections<br />

Archaeologists are in the business of turning trash<br />

into treasure. In summer 2012, Stanford archaeology<br />

students excavated broken glass bottles from<br />

the former site of the Searsville Dam on Stanford<br />

lands. While the recovered bottles no longer serve<br />

their original purpose of containing medicinal curatives,<br />

foodstuffs, and liquor, they still play a role<br />

in the narrative of Stanford history. <strong>The</strong>ir color,<br />

material, shape, size, and inscriptions communicate<br />

their age and their original contents. A bottle with a deep blue hue that once<br />

held Bromo-Seltzer, an effervescent powder that relieved stomach pain, was<br />

shipped via cross-country train from Baltimore. <strong>The</strong> coffee-brown color of these<br />

J. H. Cutter bourbon bottles protected the locally distributed whiskey within<br />

from sunlight and spoilage. <strong>The</strong> bottles, most likely discarded by the damkeeper<br />

himself, are inherently intimate objects. <strong>The</strong>y were reached for in times<br />

of pain, their curative contents ingested. All that remains is the shattered glass.<br />

Anna Toledano<br />

JANE’S JEWELRY<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

A rococo brooch, two bracelets, a hair comb, and a pair of earrings—each one<br />

a paste replica of the original—are all that remain of Jane Stanford’s prodigious<br />

jewelry collection. At one point Jane owned thirty-four different sets, valued at<br />

$500,000. Leland Stanford Sr. acquired the first of these extravagant pieces<br />

for his wife in Paris in 1880. But the opulent jewels belied his railroad’s inability<br />

to pay back government bonds. When the university fell into insolvency after<br />

Leland Sr.’s death, Jane endeavored unsuccessfully to sell the pieces abroad at<br />

Queen Victoria’s 1897 Diamond Jubilee. Two years later, she hired I. W. Tabor<br />

& Co. to photograph the collection and its “precious memories,” and she commissioned<br />

a painting of her jewels from Astley Middleton Cooper, an eccentric<br />

drunk who discreetly sold a copy of the painting to a gambling house. We do<br />

not know when the paste replicas<br />

were made—whether it was<br />

around the time Jane was trying<br />

to monetize her assets, or much<br />

earlier. In any case, a few years<br />

after her death, university trustees<br />

sold the jewels to endow the<br />

Jewel Fund, which still supports<br />

library acquisitions today.<br />

Alexander Veitch<br />

SPIRIT PHOTOGRAPH<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

Surrounded by an ethereal haze, the apparition<br />

of a beautiful young woman hovers<br />

before a thickly mustachioed Victorian<br />

gentleman. This “spirit photograph” was<br />

a gift from the youngest and purportedly<br />

most eccentric of the six Stanford brothers,<br />

Thomas Welton Stanford, who purchased<br />

it during a trip to Australia. He married in<br />

1869, but his wife died only a year later; this<br />

tragedy likely motivated his role in founding<br />

the Victorian Association of Progressive<br />

Spiritualists in 1870. Spiritualists believed<br />

that they could communicate with the dead, a notion that underpinned their<br />

religious movement. <strong>The</strong>y conducted parlor séances and circulated spirit<br />

photographs. Leland Stanford Sr. and Jane Stanford were not immune to the<br />

appeal of communicating with the afterlife, and Jane especially was drawn<br />

to Spiritualism. After the tragic loss of her son, she must have taken great<br />

comfort in the idea that he was not only at peace, but perhaps still present<br />

and even reachable in some manner.<br />

Astrid Johannah Smith<br />

POISON BOTTLE<br />

Stanford University Archaeology Collections<br />

This small, broken, cobalt-blue bottle manufactured by Whitall<br />

Tatum between 1875 and 1901 is probably from the Stanfords’<br />

medicine cabinet. Exactly what it contained is unknown, but<br />

the distinctive color and quilted-diamond pattern indicate<br />

that it was certainly a medicinal poison. During the nineteenth<br />

century, poisons enjoyed a wide variety of uses; for<br />

instance strychnine was the preferred stimulant in energy<br />

tonics. Olympic athletes used it to enhance performance,<br />

with predictably awful results. One could pop strychnine<br />

pills, use strychnine-laced ointments to increase sexual<br />

potency, or ingest small quantities for incontinence, constipation,<br />

diphtheria, chronic bronchitis, angina pectoris, heart<br />

trouble—even the typhoid fever that took the life of Leland Stanford Jr. It was<br />

regarded as a potent, all-purpose lubricant for the human system. Did a similar<br />

bottle make the voyage from California to Hawaii, where it became the<br />

means for the sudden and dramatic death of Jane Stanford on February 28,<br />

1905? She demonstrated the classic signs of strychnine poisoning.<br />

Paula Findlen<br />

24<br />

25

Leland Stanford Sr. and<br />

the Central Pacific Railroad<br />

MITCH THERIEAU<br />

PhD candidate, Modern Thought and Literature<br />

THE STORY OF THE CENTRAL PACIFIC RAILROAD IN THE 1860S BEGINS<br />

and ends with gold. Leland Stanford Sr. and Collis Huntington, who<br />

directed the railroad in its early years alongside Charles Crocker and<br />

Mark Hopkins, made their first fortunes in Sacramento selling tools to<br />

the prospectors who flocked to California in the wake of the 1849 Gold<br />

Rush. This prospect of wealth attracted <strong>The</strong>odore Judah, a New York<br />

railroad engineer fixated on the notion of building a transcontinental<br />

railroad. After a few failed efforts to fundraise, Judah persuaded Leland Sr.<br />

and his three associates to go into business with him. On June 28, 1861,<br />

on the strength of the associates’ capital and Judah’s almost evangelical<br />

enthusiasm, the Central Pacific was incorporated. <strong>The</strong> Pacific Railroad<br />

Acts of 1862 and 1864 financially supported the completion of roughly<br />

half of the transcontinental railroad, with the other half to be undertaken<br />

by the newly formed Union Pacific.<br />

In the middle of his efforts to get the Central Pacific off the ground,<br />

Thomas Hill (1829–1908), <strong>The</strong> Driving of the Last Spike, 1881.<br />

California State Railroad <strong>Museum</strong><br />

26<br />

Alfred A. Hart (1816-1906), <strong>The</strong> Last Rail Is Laid. Scene at Promontory<br />

Point, May 10, 1869, 1869. Stanford University Archives<br />

Leland Sr. was elected governor of California. A known railroad<br />

proponent, he rarely missed an opportunity to mention the benefits that<br />

long-distance rail travel would bring to the state. Even in his inaugural<br />

address, he emphasized that a transcontinental railroad would make<br />

it easier for California to trade with Nevada, where significant gold<br />

and silver deposits had been discovered. Of course, given his business<br />

arrangements, such a railroad would bring significant monetary gain<br />

to Leland Sr., too. Still, this mixing of the railroad, personal profit, and<br />

political interests cut both ways, as he used his authority as governor<br />

to raise funds for the Central Pacific. Gold helped foment the desire<br />

that gave birth to the Central Pacific, and gold had a hand in shaping<br />

its route across the West; thus, it was only appropriate that gold would<br />

commemorate its completion.<br />

On May 10, 1869, near Promontory, Utah, after more than six years<br />

of brutal exploitation and unfathomable misery on the part of Chinese<br />

migrant workers in particular, the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific<br />

were joined with a Golden Spike. Fittingly, it was Leland Sr. who gently<br />

tapped this spike into a tie made of California laurel. <strong>The</strong>n the Golden<br />

Spike was quickly un-driven, and an undocumented railroad worker<br />

drove in the iron spike that would supposedly serve as the real final link<br />

between East and West. <strong>The</strong> Golden Spike became part of the room of<br />

Stanford memorabilia installed in 1893, the year of Leland Sr.’s death,<br />

reminding visitors of the origins of the wealth that built this university.<br />

27

Immigrant Labor<br />

on the Stanford Estate<br />

LAURA JONES<br />

Director of Heritage Services and University Archaeologist<br />

BECAUSE LELAND STANFORD SR. AND JANE STANFORD WERE AMONG<br />

the richest people in the United States and widely known for their<br />

audacious ambitions, job seekers often walked the long road to their<br />

Palo Alto Stock Farm office and asked for work. <strong>The</strong> Stanfords also<br />

sought and found workers through social clubs and trade associations,<br />

often hiring based on national origin and ethnic ties. California’s<br />

perceived religious tolerance and ethnic diversity made the state a<br />

destination for European immigrants as well as immigrants from the<br />

Pacific Rim, including settlers from Mexico, Peru, Chile, China, Japan,<br />

and the Philippines.<br />

In the years just before the founding of the university, the Stanfords<br />

employed about a hundred year-round workers to tend their horses,<br />

vineyards, orchards, crops, and gardens. Nearly half of these were<br />

Chinese, with the rest hailing from the Stanfords’ home state of<br />

New York and a scattering of men from Scotland, Ireland, and<br />

England. “Gangs” of Chinese men were hired as temporary laborers<br />

to handle special projects such as the building of Lagunita Dam and<br />

the expansion of the vineyards. Although Chinese workers were not<br />

welcomed by the building trade unions, they dominated agricultural<br />

work during the construction of the university, including farming,<br />

landscaping, gardening, and work with the horses.<br />

In its early years the campus also had Chinese cooks and a Chinese<br />

laundry, and faculty homes had Chinese or Japanese servants. <strong>The</strong><br />

Stanford family had an English butler in San Francisco and a Chinese<br />

butler, Ah Sing, at their Palo Alto home. While none of the twenty-two<br />

“married men with families” who were given turkeys on Thanksgiving<br />

in 1884 were from China, at least one Chinese foreman, Jim Mock,<br />

was able to bring his wife to live on the Stanford estate. Jane Stanford<br />

gave engraved silver christening cups to the Mocks’ two sons and<br />

wrote letters of support for the family as they struggled to maintain<br />

their ties to relatives in China after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882<br />

left: Construction<br />

Gang, c. 1880–89.<br />

Stanford University<br />

Archives<br />

below: S.B. Dole<br />

(1844–1926),<br />

Cooking under<br />

Difficulties after<br />

1906 Earthquake,<br />

1906. Stanford<br />

University Archives<br />

made travel between<br />

the two countries<br />

difficult. <strong>The</strong> restrictions<br />

of the Exclusion Act<br />

diminished the number<br />

of Chinese workers in<br />

the 1890s.<br />

Trade unions and<br />

newspapers monitoring<br />

Leland Sr.’s activities<br />

closely observed the<br />

building of the university<br />

and published letters demanding that he “recognize the interests of<br />

the people of California” and not employ “foreign scabs” or “tramps” on<br />

the campus. Nearly all the construction work on the campus buildings<br />

was performed by union workers, with workers from particular<br />

immigrant groups dominating particular trades, such as brick masons<br />

from Ireland and stone cutters and carvers from Italy. Thanks to<br />

her extensive travels Jane Stanford had long-standing relationships<br />

with Italian craft workshops and paid experts from the Salviati & Co.<br />

glassworks to travel from Venice to create the mosaics on the exterior<br />

of the museum and in Memorial Church. After the 1906 earthquake,<br />

Venetian master mosaic artist Maurizio Camerino returned to the<br />

campus from Salviati & Co. to supervise reconstruction of the mosaics<br />

at Memorial Church. <strong>The</strong> family’s domestic workers were nearly all<br />

foreign born; most of the women on Jane’s long list of maids had<br />

immigrated from Ireland, England, or Germany.<br />

28<br />

29

<strong>The</strong> Palo Alto Stock Farm<br />

MAHPIYA VANDERBILT<br />

Stanford ’19<br />

AFTER THE COMPLETION OF THE TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD<br />

in 1869, Leland Stanford Sr. was exhausted. His doctor prescribed<br />

a vacation, but instead he purchased Occident, “a little horse that<br />

turned out remarkably fast.” His fascination with horses led to the<br />

establishment of the Palo Alto Stock Farm in 1876, an enterprise that<br />

eventually grew to cover more than eight thousand acres of Santa<br />

Clara Valley land and included barns for colts and trotters in training,<br />

a carriage house with second-floor staff residences, blacksmiths’ and<br />

wheelwrights’ shops, dozens of paddocks, and multiple racetracks.<br />

In winter 1876 Leland Sr. significantly expanded the operation by<br />

acquiring twelve mares and his prize sire, Electioneer, from the New York<br />

stud farm Stony Ford for $41,200. His objective was to set speed records<br />

in harness racing, then the most popular racing sport, by breeding and<br />

training the best trotters in the world. By 1882 there were more than 350<br />

horses on the farm, and by 1891 approximately 750 horses, making it one<br />

of the largest training facilities in the United States. At its peak the Stock<br />

Farm employed almost 150 people, many of them Chinese immigrants,<br />

to feed, train, and care for the horses as well as maintain tracks, farm the<br />

land, and operate and repair equipment.<br />

To this day, the Palo Alto Stock Farm is renowned for its creation<br />

of a new and innovative training system to increase speed. Developed<br />

with trainer Charles Marvin, the method involved running horses in<br />

short bursts starting at a young age. After Leland Sr.’s death in 1893<br />

Jane Stanford continued the farm in her husband’s memory, but she<br />

finally closed it in 1903 and all the horses were auctioned off. Today, its<br />

legacy lives on in the university’s nickname, “<strong>The</strong> Farm.”<br />

Horse Relics<br />

ALEXANDER VEITCH<br />

Stanford ’19<br />

<strong>The</strong> Red Barn on the Palo Alto Stock Farm, late 1880s.<br />

Stanford University Archives<br />

30<br />

THE PALO ALTO STOCK FARM WAS MORE THAN MERELY THE<br />

precursor of Stanford University; it was the epicenter of a sporting<br />

empire that remains unparalleled in horse racing and beyond. <strong>The</strong><br />

farm produced California’s first celebrity athletes—equine rather<br />

than human—many of whose speed records stand unbroken today. In<br />

Leland Stanford Sr.’s estimation, the success of his racing “trotters”<br />

rivaled his achievements as a railroad magnate. Oddly enough, relics<br />

of the Stanfords’ horses expose a great deal about the new Californian<br />

elite of the Victorian era. As products of wealth and science, horses<br />

projected the status of their breeders. Leland Sr. preserved traces<br />

of his most prized horses as instantiations of his own manifest<br />

superiority. <strong>The</strong>se mementos ranged from the artistic and aesthetic to<br />

the anatomical and macabre.<br />

In 1891, the newly mounted skeleton of Electioneer, the farm’s<br />

greatest sire, was readied for display to great fanfare in the Leland<br />

Stanford Junior <strong>Museum</strong>. A horse that bred but never raced,<br />

Electioneer stood for a perfect genomic type, one that echoed the<br />

racial science of the era. After viewing the skeleton, one journalist<br />

31

Palo Alto Spring:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Martyrdom of Time<br />

ALEXANDER NEMEROV<br />

Carl and Marilynn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities<br />

Ears of the Trotting Champion Electioneer (1868–1890), 1890.<br />

Cantor Arts Center<br />