Gallery Guide | The Melancholy Museum

Using over 700 items from the Stanford Family Collections, artist Mark Dion’s exhibition "The Melancholy Museum" explores how Leland Stanford Jr.’s death at age 15 led to the creation of a museum, university, and—by extension—the entire Silicon Valley.

Using over 700 items from the Stanford Family Collections, artist Mark Dion’s exhibition "The Melancholy Museum" explores how Leland Stanford Jr.’s death at age 15 led to the creation of a museum, university, and—by extension—the entire Silicon Valley.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Sacramento business partners. <strong>The</strong> influx of multiethnic European Americans,<br />

Chinese, and South American migrant laborers as well as free and enslaved<br />

Black Southerners who traveled to participate in the Gold Rush drastically<br />

changed California’s demographics. At the same time, the local Native Americans<br />

who were the land’s original inhabitants were starved, displaced, and<br />

murdered. <strong>The</strong> opportunities and tragedies of the Gold Rush and the industries<br />

it spawned invigorated California’s economy, making statehood possible in the<br />

Compromise of 1850, which allowed California to enter the Union and raised<br />

pertinent questions regarding the slave industry across the country.<br />

Liv Porte, Curatorial Assistant, Cantor Arts Center<br />

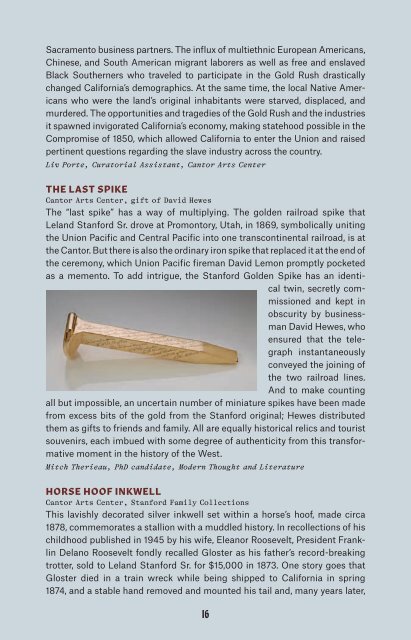

THE LAST SPIKE<br />

Cantor Arts Center, gift of David Hewes<br />

<strong>The</strong> “last spike” has a way of multiplying. <strong>The</strong> golden railroad spike that<br />

Leland Stanford Sr. drove at Promontory, Utah, in 1869, symbolically uniting<br />

the Union Pacific and Central Pacific into one transcontinental railroad, is at<br />

the Cantor. But there is also the ordinary iron spike that replaced it at the end of<br />

the ceremony, which Union Pacific fireman David Lemon promptly pocketed<br />

as a memento. To add intrigue, the Stanford Golden Spike has an identical<br />

twin, secretly commissioned<br />

and kept in<br />

obscurity by businessman<br />

David Hewes, who<br />

ensured that the telegraph<br />

instantaneously<br />

conveyed the joining of<br />

the two railroad lines.<br />

And to make counting<br />

all but impossible, an uncertain number of miniature spikes have been made<br />

from excess bits of the gold from the Stanford original; Hewes distributed<br />

them as gifts to friends and family. All are equally historical relics and tourist<br />

souvenirs, each imbued with some degree of authenticity from this transformative<br />

moment in the history of the West.<br />

Mitch <strong>The</strong>rieau, PhD candidate, Modern Thought and Literature<br />

HORSE HOOF INKWELL<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

This lavishly decorated silver inkwell set within a horse’s hoof, made circa<br />

1878, commemorates a stallion with a muddled history. In recollections of his<br />

childhood published in 1945 by his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, President Franklin<br />

Delano Roosevelt fondly recalled Gloster as his father’s record-breaking<br />

trotter, sold to Leland Stanford Sr. for $15,000 in 1873. One story goes that<br />

Gloster died in a train wreck while being shipped to California in spring<br />

1874, and a stable hand removed and mounted his tail and, many years later,<br />

16<br />

presented it in 1930 to Roosevelt, who<br />

hung it in the governor’s mansion and<br />

subsequently his White House bedroom<br />

as a memento of his Hudson<br />

Valley boyhood. In reality, Roosevelt’s<br />

father, James, sold Gloster to another<br />

New York horse breeder, Alden Goldsmith,<br />

who sent the horse out West<br />

to race against Stanford’s prize horse<br />

Occident. Gloster died of lung fever<br />

in San Francisco on October 30, 1874,<br />

after a private contest but before the<br />

public race. <strong>The</strong>reafter, the Golden<br />

Gate Agricultural Association had one of Gloster’s hooves mounted and<br />

adorned with precious Western metals. But they neglected to pay the jeweler,<br />

and so the jeweler sold the item to a Richard T. Carroll in 1879, who in turn<br />

returned it to Goldsmith. How or when Leland Sr. acquired it, or whether this<br />

is a different hoof, similarly mounted, remains unknown.<br />

Mikaela Berkeley, Stanford ’20 and Paula Findlen, Ubaldo Pierotti<br />

Professor of Italian History<br />

E. E. ROGERS, ELECTIONEER<br />

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford Family Collections<br />

A dark bay horse with white pasterns on the hind legs, measuring about 15.2<br />

hands (roughly five feet) tall at the withers, Electioneer (1868–1890) was a pillar<br />

of Leland Stanford Sr.’s Palo Alto Stock Farm. Stanford purchased the virtually<br />

untested Electioneer for $12,000 in 1876. <strong>The</strong> horse, described by trainer<br />

Charles Marvin as “the perfection of driving power,” became foundational to<br />

the growth of the Stock Farm. Using Electioneer purely as a stud horse, Stanford<br />

experimented with different breeding and training techniques to produce<br />

the world’s fastest trotters. As a result of the “Palo Alto system,” even today<br />

Electioneer’s descendants hold virtually all trotting and pacing speed records.<br />

<strong>The</strong> little-known artist E. E. Rogers created this somewhat inaccurate painting<br />

of Electioneer in 1889. <strong>The</strong><br />

actual horse did not have spots<br />

on his shoulder, and his hooves<br />

were all the same color. Most<br />

likely these mischaracterizations<br />

resulted from the painting<br />

being based on an imperfect<br />

photograph.<br />

Mahpiya Vanderbilt, Stanford<br />

’19 and Alexander Veitch,<br />

Stanford ’19<br />

17