Insight 2012

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

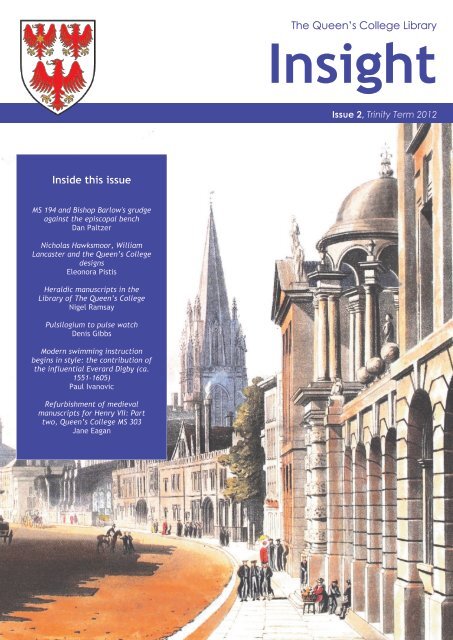

The Queen’s College Library<br />

<strong>Insight</strong><br />

Issue 2, Trinity Term <strong>2012</strong><br />

Inside this issue<br />

MS 194 and Bishop Barlow's grudge<br />

against the episcopal bench<br />

Dan Paltzer<br />

Nicholas Hawksmoor, William<br />

Lancaster and the Queen’s College<br />

designs<br />

Eleonora Pistis<br />

Heraldic manuscripts in the<br />

Library of The Queen’s College<br />

Nigel Ramsay<br />

Pulsilogium to pulse watch<br />

Denis Gibbs<br />

Modern swimming instruction<br />

begins in style: the contribution of<br />

the influential Everard Digby (ca.<br />

1551-1605)<br />

Paul Ivanovic<br />

Refurbishment of medieval<br />

manuscripts for Henry VII: Part<br />

two, Queen’s College MS 303<br />

Jane Eagan

2<br />

W<br />

elcome to the second issue of<br />

<strong>Insight</strong>, the annual publication<br />

which seeks to highlight some of<br />

the treasures of the Queen’s<br />

Library, both to members of the College and to a<br />

wider audience at home and further afield.<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

In this issue we again have a variety of articles on<br />

printed book and manuscript collections in the<br />

Library, both from regular readers of the collections<br />

and from members of the Library team.<br />

These include an article on the Library’s large<br />

collection of heraldic manuscripts by Nigel<br />

Ramsay of University College London, and an<br />

account of Thomas Barlow’s grudge against the<br />

Episcopal bench by Dan Paltzer, who spent several<br />

weeks in the Library last summer researching<br />

Barlow for his PhD thesis. Denis Gibbs, who has<br />

been visiting the Library to consult our early<br />

medical collection since the 1960s, has written<br />

about Sir John Floyer, whose collection in the<br />

Library formed the basis of a successful cataloguing<br />

and conservation project funded by the<br />

Wellcome Trust some years ago. Paul Ivanovic,<br />

our rare books cataloguer, has contributed an<br />

article about his favourite printed book in the<br />

Library, Everard Digby’s De arte natandi, while<br />

Jane Eagan, our head conservator, has written the<br />

second in her series on the refurbishment of our<br />

Henrician medieval<br />

manuscripts.<br />

Fig. 1: Frontispiece<br />

depicting Charles II, from<br />

the first volume of Wood’s<br />

Historia et antiquitates<br />

Universitatis Oxoniensis ,<br />

recently bequeathed to the<br />

Library by old member Mr<br />

J. A. Colmer. The Sheldonian<br />

Theatre can be seen in<br />

the background. (Sel.b.281a)<br />

Over the last year we<br />

have received several<br />

visits from groups<br />

interested in our<br />

fascinating collection of<br />

original Hawksmoor<br />

propositions for the rebuilding<br />

of the College<br />

in the early eighteenth<br />

century, and I am<br />

particularly pleased to<br />

be able to include in<br />

this issue an article<br />

about Hawksmoor’s<br />

designs for Queen’s by<br />

Eleonora Pistis of<br />

Worcester College,<br />

Oxford.<br />

It is not often that we<br />

add to our historic<br />

collections but this year,<br />

as a result of the sad<br />

death of old member Mr<br />

Fig. 2: p. 125 and facing plate showing an illustration of<br />

Queen’s Chapel, from Ackermann’s A history of the<br />

University of Oxford, recently bequeathed to the Library by<br />

old member Mr J. A. Colmer. (Sel.c.200a)<br />

J. A. Colmer in late 2011, we received a bequest of<br />

23 early printed books. Many of the volumes are<br />

extremely rare including a copy of Anthony<br />

Wood’s 1674 Historia et antiquitates universitatis<br />

Oxoniensis bound in two volumes interleaved with<br />

Loggan’s 1675 Oxonia illustrate (fig. 1). Another<br />

wonderful addition to our collection of antiquarian<br />

material relating to Oxford is Ackermann’s 1814<br />

two volume History of the University of Oxford<br />

(fig. 2) containing exquisite prints of College and<br />

University buildings which, rather surprisingly, we<br />

did not have in the collection previously. One of<br />

the most interesting parts of the collection are the<br />

five volumes of East India tracts including a<br />

number of items not held by the British Library<br />

until Mr Colmer provided copies of some of them.<br />

The collection as a whole is an extremely welcome<br />

addition to the College Library and I am most<br />

grateful to Mr Colmer for remembering us in this<br />

particularly generous way.<br />

As last year I am most grateful to all the contributors<br />

to this issue of <strong>Insight</strong> and in particular to<br />

Lynette Dobson who has produced the Newsletter<br />

for us.<br />

If you have ideas for future articles or indeed<br />

would like to contribute, please contact me at<br />

amanda.saville@queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Amanda Saville<br />

Librarian<br />

June <strong>2012</strong><br />

Cover image: Section of illustration of High<br />

Street, Oxford from Ackermann’s A history of the<br />

University of Oxford.

MS 194 and Bishop Barlow's grudge against the episcopal bench 3<br />

MS 194 and Bishop Barlow's grudge<br />

against the episcopal bench<br />

Dan Paltzer<br />

University of Minnesota<br />

W<br />

hen I came to the Library at<br />

Queen’s College last summer, I<br />

was searching for the answer to a<br />

deceptively simple question. Why<br />

would a seventeenth-century Anglican bishop<br />

write a pamphlet arguing that none of the bishops<br />

should be allowed to participate in the Earl of<br />

Danby’s impeachment before the House of Lords?<br />

Such a pamphlet contradicts everything which one<br />

would expect of a bishop from that day. Yet this<br />

was exactly the position that Thomas Barlow, the<br />

Bishop of Lincoln, took in his pamphlet A discourse<br />

of the peerage & jurisdiction of the lords<br />

spiritual in Parliament (1679). This pamphlet was<br />

Barlow’s intervention in an ongoing debate about<br />

whether the bishops could participate in the<br />

impeachment trial or attainder of Charles II’s chief<br />

minister. From the evidence he found in legal<br />

records, Barlow concluded that the bishops were<br />

legally banned from such proceedings.<br />

This was a very strange position for Barlow to<br />

take, and one which seemingly violated his usual<br />

political convictions as a staunch royalist. Danby<br />

was under attack by the Earl of Shaftesbury, who<br />

therefore wanted to prevent the bishops from<br />

voting to acquit Danby in this capital trial.<br />

Shaftesbury therefore unburied an old custom that<br />

had roots in canon law which prevented clergymen<br />

from judging “cases of blood”.<br />

Oddly enough, Barlow agreed with Shaftesbury<br />

and argued that the bishops should withdraw from<br />

all cases of blood. I find this position odd, because<br />

it contradicts the theological and political positions<br />

which Barlow defended in all of his other<br />

publications as well as most of the manuscript<br />

treatises he left in the Queen’s College Library.<br />

For the sake of comparison, consider De Jure<br />

Regio Monarchiae Anglicanae (MS 194), where<br />

Barlow proved himself to be a firm supporter of<br />

the divine right of kings. This short treatise was<br />

actually written to contradict Shaftesbury, even<br />

though a few years later he would take the Earl’s<br />

side on the issue of bishops during capital trials.<br />

This piece proclaimed an ideology which one<br />

would expect from an Anglican bishop. Shaftesbury<br />

had delivered a speech to the House of Lords<br />

on 20 Oct 1675 in which he claimed the doctrine of<br />

the divine right of kings was the most dangerous<br />

and destructive doctrine there had ever been to<br />

English government and law. Furthermore, it was<br />

a relatively new error introduced by the Laudian<br />

clergy. Barlow dismissed this idea on three<br />

counts. Divine right was neither new, nor dangerous,<br />

nor destructive. The doctrine had a strong<br />

basis in Scripture, and had even been revealed to<br />

pagans through the use of natural reason. Therefore,<br />

the King of England (and, by implication, all<br />

other legitimate monarchs) held his crown by the<br />

will of God, and not from the Pope, the people, or<br />

laws of England.<br />

The dilemma which brought me to Queen’s was<br />

how to explain the position in the pamphlet<br />

concerning bishops and cases of blood, because<br />

this publication supported the political machinations<br />

of a man whose ideology Barlow generally<br />

opposed. In the manuscript described above, as<br />

well as his other publications from the 1670s and<br />

early 1680s, Barlow consistently supported the<br />

political positions associated with the Tory side of<br />

the Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis. He remained<br />

a steadfast proponent of the established,<br />

episcopal Church of England and a firm supporter<br />

of the Stuart dynasty until just before the Glorious<br />

Revolution. So what would cause a bishop to<br />

argue a position which would effectively weaken<br />

the political position of bishops by removing them<br />

from important matters which came before the<br />

House of Lords?<br />

As it turns out, Barlow’s position was conditioned<br />

by ongoing disagreements between himself and<br />

the rest of the episcopal bench. In The state of the<br />

controversy between the Rt. Revd John Ld Bishop<br />

of Oxon and ye Bishop of Lincolne about ordination<br />

in Q. Coll. Chappell. 1676 (MS 194 - fig. 1<br />

overleaf), Barlow described his side of an argument<br />

between himself and John Fell, the aforementioned<br />

Bishop of Oxford. The conflict Barlow<br />

described was simultaneously based on his<br />

personal preference to remain in the congenial<br />

habitations at Queen’s College and his ideological<br />

commitment to maintaining Oxford University<br />

and its constituent colleges’ rights to autonomy.<br />

Barlow’s account of the spat focused primarily on<br />

the legality of his actions under English law, with<br />

occasional claims that he did not act against<br />

Christian doctrine and insults for his opponent<br />

thrown in for good measure. The difficulties

4<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

outside of them but still within English society,<br />

such as Presbyterians or leaders of the political<br />

opposition to the Crown (such as Shaftesbury in<br />

the example above). The task of writing this<br />

defence against Fell combined both institutional<br />

allegiances and personal preference, and it<br />

therefore contrasted with the way he wrote in<br />

other pamphlets or treatises.<br />

Fig. 1: Title page for Barlow’s letter The state of the controversy<br />

between the Rt. Revd John Ld Bishop of Oxon and ye Bishop of<br />

Lincolne about ordination in Q. Coll. Chappell. 1676. (MS 194)<br />

began when Fell sent Barlow a letter mere hours<br />

before Barlow was scheduled to begin ordaining<br />

new clergymen for his diocese in the chapel of<br />

Queen’s College. The letter asked Barlow not to<br />

proceed with the ordination, but Barlow saw no<br />

reason why he could not go ahead with the<br />

ceremony. After the ordination, Barlow sent Fell a<br />

letter explaining why these affairs were none of the<br />

Bishop of Oxford’s business. The University of<br />

Oxford, and all of its constituent colleges, had<br />

never really been under the episcopal authority of<br />

the local diocese. Ironically enough, until Henry<br />

VIII created a new bishopric in Oxford, the town<br />

was part of the diocese of Lincoln, which was<br />

Barlow’s see. However, Barlow claimed the<br />

Bishops of Lincoln had never been allowed to<br />

exercise authority over the University of Oxford.<br />

The Provosts of the University and visitors of<br />

particular colleges administered colleges’ spiritual<br />

and administrative affairs without interference<br />

from the Bishops of Lincoln. The 1541 charter<br />

which created the new bishopric in Oxford<br />

expressly preserved these rights and privileges.<br />

Fell had no jurisdiction over Queen’s College.<br />

Barlow had received permission from the proper<br />

authorities at Queen’s, therefore he felt he had<br />

acted within the bounds of clerical and legal<br />

propriety.<br />

The wonderful thing about MS 194 is that it<br />

humanizes an otherwise abstract vision of ideological<br />

allegiances in seventeenth-century England.<br />

In broad terms, Barlow’s ideological positions<br />

on matters such as divine right monarchy or<br />

bishops’ spiritual powers reflected the official<br />

policies of the Anglican Church. He defended<br />

these institutions from opponents who were<br />

MS 194 reveals a different kind of conflict, because<br />

it was between different factions of institutional<br />

insiders. Barlow’s conflict with the other bishops<br />

stemmed from his refusal to leave Queen’s College<br />

and take up residence at Lincoln. This was a man<br />

who loved life at Queen’s College (and if the people<br />

at Queen’s in his day were half as friendly and<br />

helpful as the current library staff of Amanda,<br />

Lynette, Rory, and Tessa, I can’t really blame him<br />

for not wanting to go). Due to this affection,<br />

Barlow wanted to preserve the administrative<br />

autonomy of the Oxford University colleges (and<br />

Queen’s in particular), because this autonomy<br />

allowed his college to continue to function in its<br />

traditional modes. Legal documents such as<br />

Parliamentary statutes and royal charters were the<br />

instruments establishing and protecting that<br />

autonomy, so Barlow fiercely defends the entire<br />

system which perpetuated these protections.<br />

In practical terms, this defence required him to<br />

protect the integrity of the common law from any<br />

outsiders (including the other bishops) who might<br />

try to interfere in college business. In order to<br />

make sure he could keep out anyone who wanted<br />

to intrude where he thought they did not belong,<br />

Barlow needed to ensure the integrity of the<br />

institutional elements responsible for protecting<br />

and enforcing English law. The House of Lords<br />

was one of these elements, insofar as certain types<br />

of cases were heard before that body. In all of his<br />

publications, Barlow wished to maintain a particular<br />

ideological understanding of how elements<br />

within English society relied upon each other and<br />

ought not to overstep their bounds to transgress<br />

upon other institutions’ traditional functions.<br />

However, MS 194 showed that he had personal<br />

reasons for this as well. The conflict between<br />

himself and the other bishops made him suspicious<br />

that the other prelates were willing to<br />

overstep such boundaries, which in turn explains<br />

why he could oppose Shaftesbury’s policies<br />

generally while also writing a pamphlet intended<br />

to show that bishops should not judge Danby’s<br />

trial.

Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Lancaster and the Queen’s College designs 5<br />

Dan Paltzer is a PhD candidate of the Department<br />

of History at the University of Minnesota-Twin<br />

Cities. Prior to arriving at Minnesota, he was a<br />

Government major at Lawrence University in<br />

Appleton, WI (BA) and a graduate student in the<br />

Department of Political Science at Vanderbilt<br />

University (MA) where he studied Political<br />

Theory. His political theory background led him<br />

into an interest in early modern political thought<br />

and its place within broader intellectual trends of<br />

the time period running roughly from 1500-<br />

1800. His dissertation research involves the<br />

ways in which English pamphleteers interpreted<br />

history through ideological lenses during the<br />

1680's.<br />

Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Lancaster<br />

and the Queen’s College designs<br />

Eleonora Pistis<br />

Worcester College, Oxford<br />

O<br />

n 6th February 1710, coincident with<br />

Queen Anne’s birthday, the Vice-<br />

Chancellor of Oxford University<br />

William Lancaster (1650–1717) laid the<br />

foundation stone for a new Queen’s College, of<br />

which he had been Provost since 1704 (fig. 1). 1 In<br />

1714, John Ayliffe wrote that, when finished, the<br />

new building would be ‘one of the most Majestick<br />

Pieces of Architecture in the whole Kingdom.’ 2<br />

During Lancaster’s Vice-Chancellorship (1706–<br />

1710) – and most likely between 1708 and 1709 4 –<br />

another figure drew up different preliminary<br />

designs: the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661–<br />

1736). Hawkmoor’s contribution amounts to<br />

twenty drawings, still kept in Queen’s Library,<br />

representing seven different projects which the<br />

architect entitled Propositions. 5<br />

Fig. 1: William Lancaster<br />

(1650-1717)<br />

As has already been pointed out, the final design<br />

of Queen’s College’s cannot be regarded as the<br />

work of a single mind. 3 It is usually ascribed to the<br />

amateur architect Dr. George Clarke, with the<br />

assistance of the master mason William Townesend.<br />

The majority of these<br />

designs have already<br />

been published and<br />

discussed in the<br />

scholarly literature. 6<br />

Within what Colvin<br />

c a l l e d ‘ U n b u i l t<br />

Oxford,’ Hawksmoor’s<br />

propositions are<br />

usually regarded as<br />

the ‘fiasco’ 7 of an<br />

‘expensive architect<br />

with a penchant for<br />

adding extravagant<br />

and functionally<br />

unnecessary gestures.’<br />

8 But was there a<br />

r e a s o n b e h i n d<br />

Hawksmoor’s ‘extravagant’ solutions? Should his<br />

designs be considered a failure? The aim of this<br />

brief contribution is to analyse Hawksmoor’s<br />

designs in the context of his relationship with his<br />

patron, in order to identify his main aims and<br />

reevaluate his achievements.<br />

The designs for Queen’s mark the beginning of the<br />

history which bound Hawksmoor to the city of<br />

Oxford for nearly three decades (ca. 1708–1736).<br />

They are addressed to William Lancaster, at that<br />

time the most powerful figure within the University<br />

and a man with an interest in architecture –<br />

potentially a perfect patron. Lancaster’s interest in<br />

architecture is confirmed by the presence of his<br />

name in a plate from the Vitruvius Britannicus<br />

(1715) which illustrates a design by Colen Campbell<br />

for a church on Lincoln’s-Inn Fields, dated<br />

1712 9 ; while his involvement in Oxford’s architectural<br />

activities is confirmed by Thomas Hearne,<br />

who, in reference to William Townesend, wrote:<br />

‘a great many justly wonder that he should have<br />

been so much made use of by the University. But<br />

this, I believe, is owing in good measure to Dr.<br />

George Clarke of All Souls, as it was also to Dr.<br />

Lancaster of Queen’s.’ 10<br />

Certain aspects of Hawksmoor’s drawings for<br />

Queen’s College confirm that the architect must<br />

have been aware of Lancaster’s potential as<br />

architectural patron. Various annotations demonstrate<br />

that this set of drawings was conceived as an<br />

introductory portfolio addressed not simply to the<br />

Provost of the College, but to the Vice-Chancellor.<br />

With a great deal of insistence, in fact, in more<br />

than one drawing Hawskmoor craftily indicates<br />

the ‘Vice Chancellor’s lodgings’. 11

6<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

The Queen’s designs can be distinguished within<br />

the whole corpus of Hawksmoor’s designs for<br />

Oxford 12 based on three main characteristics. The<br />

first is the exceptionally large size of the sheets,<br />

which measure up to 0.52 by 1.385 metres. The<br />

second is the accuracy of the drawings. Although it<br />

is true that some are unfinished and several are by<br />

an assistant, 13 the propositions which Hawksmoor<br />

labeled ‘A’ and ‘IV’ are particularly well-defined.<br />

The third, as we will see, is the propositions’<br />

provocative character relative to the Oxford<br />

architectural tradition, in terms of both typology<br />

and language.<br />

If the first two characteristics are compatible with<br />

the intention of receiving the Queen’s’ commission,<br />

the third reveals a broader and slightly<br />

different purpose. In the absence of any precise<br />

indications dictated by the prospective client, 14<br />

Hawksmoor demonstrated his ability to elaborate<br />

infinite typological solutions in plan and volume,<br />

using a language composed of an extraordinary<br />

wide range of sources. Hawksmoor’s main aim<br />

seems to have been to present himself to Lancaster<br />

as the right architect not only for Queen’s, but<br />

potentially for any building, with skills that would<br />

have distinguished himself from amateurs or<br />

master masons.<br />

Hawksmoor’s propositions reveal the architect’s<br />

strategy in front of his new client. Queen’s presented<br />

Hawksmoor with his first opportunity to<br />

consider how to shape a college from scratch, a<br />

subject to which he would return many times in<br />

the next twenty-five years. He began by organizing<br />

the college around two regular quadrangles, as in<br />

Clarke’s contemporary masterplan for All Souls,<br />

with a symmetry and regularity that was completely<br />

new to Oxford. There was, however, one<br />

crucial difference: at Queen’s College, the Old<br />

Library and the newly built north range were<br />

already existing elements which Hawksmoor was<br />

obliged to incorporate into his project. 15 This is the<br />

reason why, in all of the propositions, the second<br />

quadrangle is always less prominent, while in<br />

Clarke’s masterplan for All Souls it is the most<br />

important element. 16 With a radically different<br />

approach, Hawksmoor focused on the definition of<br />

the first quadrangle, which in PROPOSITION V,<br />

QUEEN’S 14 and 15 (fig. 2, top left), he expanded to<br />

occupy all of the available area. In designing the<br />

entrance of the latter, he employed an erudite<br />

quotation: the vestibule of the Palazzo Farnese in<br />

Rome.<br />

Fig. 2: Plan drawings of Hawksmoor’s propositions. Left to<br />

right, top to bottom: Queen’s 15 ; Proposition III ; Queen’s<br />

17 ; Proposition II ; Proposition A ; Proposition IV.<br />

With the balance between the two quadrangles<br />

abolished, Hawksmoor next concentrated on the<br />

two vital nuclei of any college, the hall and chapel.<br />

These became the crux of the project. In PROPOSI-<br />

TION I, the hall and chapel are along the High<br />

Street, whereas in almost all of the other proposals<br />

the hall and chapel, or the chapel alone, are<br />

instead positioned in the range that separates the<br />

two quadrangles.<br />

The central position of the hall and chapel,<br />

provided an opportunity for Hawksmoor to design<br />

various innovative solutions that transformed the<br />

transversal range into a complex organism, one<br />

that is moulded and expands to the point that in<br />

PROPOSITION III (fig. 2, top centre) it occupies<br />

much of the second quadrangle. Here the hall and<br />

chapel are connected by a semicircular colonnade,<br />

with a couple of twin columns positioned in a<br />

radial perspective, interrupted by a telescopic<br />

passageway that frames a peripteral temple<br />

against the north range. It is a solution reminiscent<br />

of the screen of columns present in a preliminary<br />

design for Greenwich. The most direct<br />

source, however, is Bernini’s St Peter’s Square,<br />

depictions of which abounded in the libraries of<br />

Oxford of the time.<br />

In other proposals the chapel is detached or semidetached<br />

at the centre of a large court. In PROPOSI-<br />

TION VI and its variation QUEEN’S 17 (fig. 2, top<br />

right) it has an oval structure, which perhaps<br />

alludes to Bernini’s third design for the Louvre,<br />

which would have been familiar to Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Lancaster and the Queen’s College designs 7<br />

Fig. 3: Proposition IV, High Street elevation.<br />

from the engravings in the Grand Marot and<br />

probably from the enthusiastic descriptions by<br />

Christopher Wren, who appreciated models of the<br />

scheme when he visited Paris in 1665. In PROPOSI-<br />

TION II (fig. 2, bottom left), as in QUEEN’S 14, the<br />

chapel becomes a peripteral temple.<br />

Fig. 4: Proposition IV, front quadrangle, east-west section<br />

showing the north side elevation.<br />

By using a court layout with a church at the centre<br />

of the rear range, as in PROPOSITION A (fig. 2,<br />

bottom centre) Hawksmoor seems to refer in part<br />

to Solomon’s Temple, as designed by Villalpando<br />

and reinterpreted in the Escorial and later also in<br />

the Hôtel des Invalides. 17 But this later reference is<br />

only a part of a wider focus on French sources,<br />

well known thanks to George Clarke’s print<br />

collections. 18 Hawksmoor not only seems to refer<br />

to Louis Le Vau’s designs for the Louvre<br />

(PROPOSITION A), but in QUEEN’S 17 he also<br />

designed the first quadrangle with a concave side<br />

after the model of countless Parisian Hôtels. He<br />

also adopted the structure of the rusticated<br />

gateway from the Palais du Luxembourg – see<br />

PROPOSITION VI.<br />

As Downes pointed out, PROPOSITIONS A and IV<br />

are the only ones to have been developed entirely<br />

and coherently. As we have seen, they are the most<br />

accurate and contain references to the Vice-<br />

Chancellor Lancaster.<br />

PROPOSITION IV (fig. 2, bottom right) is illustrated<br />

in five drawings. The gateway at the centre of the<br />

monumental High Street front is framed in a<br />

stunning and out-of-scale manner by two huge<br />

composed Doric columns, sixty feet tall (fig. 3).<br />

This astonishing entrance evokes the Gothic access<br />

towers of medieval cloisters, but interprets its<br />

vertical development in terms of archaic monumentality,<br />

as that of the Pillars of Hercules. Going<br />

through the High Street entrance, one would<br />

Fig. 5: Proposition A, High Street elevation.<br />

arrive in the first quadrangle. The hall and the<br />

chapel are en pendant in the north range and<br />

divided by a vestibule (fig. 2-4). 19 The lateral sides<br />

of the façade clearly evoke the lateral facades of<br />

the court of the Curia Innocenziana in Rome,<br />

whereas the fenestration, with large headed<br />

windows set within deep concave recesses, recalls<br />

the niches of the drum of St Paul’s. The façade of<br />

the central vestibule is a tetrastyle pronaos that, as<br />

in the Basilica Aemilia, ends in a terminal column<br />

flanked by a pilaster, a device that had been<br />

employed already in one of the preliminary<br />

projects for Greenwich Hospital and later at<br />

Blenheim. Onto the quadrangular vestibule is<br />

grafted a low octagonal drum flanked by cinerary<br />

urns superimposed on sacrificial altars. On this<br />

low drum is a second one, higher and articulated<br />

by paired columns and by hefty buttresses that<br />

frame wide openings: the model is Michelangelo’s<br />

drum at St Peter’s in the Vatican, mediated by the<br />

combination of pronaos and attic of the Sant’Agnese<br />

in Rome, whereas the buttresses are modelled<br />

on Borromini’s Sant’Ivo. This powerful<br />

structural system surprisingly supports a lowtiered<br />

dome with steps based on the model of the<br />

Pantheon.<br />

PROPOSITION A (fig. 2, bottom centre), illustrated<br />

in four large designs, is based on the other projects:<br />

from PROPOSITION I it takes the position of

8<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

Fig. 7: Proposition A, front quadrangle, north-south section<br />

showing the west side elevation.<br />

Fig. 6: Proposition A, front quadrangle, east-west section<br />

showing the north side elevation.<br />

the hall along the High Street; from PROPOSITION<br />

IV, at least in part, it takes the layout of the east<br />

and west ranges; from PROPOSITIONS VI it takes<br />

the idea of a central chapel with an interior dome,<br />

from PROPOSITION V the arrangement of the<br />

Chapel. The façade of the college along High Street<br />

is characterized by a rusticated arcade surmounted<br />

by a main floor with giant Corinthian pilasters and<br />

by an attic floor (fig. 5). The central section of the<br />

façade is marked by a three bay recess, which<br />

forms a sort of triumphal arch, as in Le Vau’s<br />

design for the east façade of the Louvre (1664) .<br />

But here the central arch overruns the main floor<br />

and becomes a podium with French ornamentation<br />

that bears a female figure, perhaps Queen<br />

Anne. Going through the entrance vestibule, one<br />

would enter the first quadrangle. The north range<br />

(fig. 6) is dominated by the chapel orientated west<br />

-east, the south façade of which is a hexastyle<br />

pronaos of the Corinthian order two bays deep, a<br />

solution that Hawksmoor would use again in St.<br />

George’s in Bloomsbury (1713–1715). The pronaos<br />

is flanked on both sides by a single-storey rusticated<br />

arcade that leads to two symmetrical<br />

staircases, which give access to two lofty towers.<br />

These elements, with screens of columns and<br />

broken-based pediments, are characterised by<br />

ancient-style features reminiscent of Roman<br />

baths, probably mediated through Palladio. 20 The<br />

two side facades are composed of rusticated<br />

arcades, a main floor and attic (fig. 7). The ground<br />

-floor arcade is taken from the courtyard of<br />

Palazzo Thiene in Vicenza as illustrated in Palladio’s<br />

Four Books. 21 The monumental first floor is<br />

organised by raised bands, that evoke a trabeated<br />

system and frame double-level fenestration. The<br />

centre of the façade is marked with a curvilinear<br />

pediment free of any decoration.<br />

In sum, Hawksmoor drew up at least seven<br />

different innovative proposals for a new Queen’s<br />

College. By disrupting the traditional quadrangle<br />

structure, he concentrated on the hierarchic<br />

coordination between the various parts, orchestrating<br />

high and low elements and creating visual<br />

axes and sudden vistas. He employed a vast<br />

repertoire of architectonic sources taken from<br />

English tradition, but most of all from France and<br />

from ancient and modern Rome. Evocations of the<br />

Pantheon, St Peter’s, Hellenistic and Imperial<br />

architecture are combined together with references<br />

to Michelangelo, Palladio, Salomon de<br />

Brosse, Jones, Webb, Bernini, Borromini, Le Vau,<br />

Carlo Fontana, Hardouin-Mansart, Wren, and<br />

Vanburgh.<br />

Hawksmoor put on show his power of elaborating<br />

almost infinite architectonic solutions, suggesting,<br />

at the same time, the impossibility of an a priori<br />

selection without further indications from the<br />

prospective client. Every final decision, in fact,<br />

would have involved deep reflection on the<br />

ultimate purposes of the building, and this was<br />

evidently the task of Lancaster and his Fellows.<br />

The design that was finally approved demonstrates<br />

the reception of Hawksmoor’s suggestions. 22 The<br />

position of chapel and hall are connected by a<br />

Fig. 8: Queen’s today, front quadrangle, east side elevation.

Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Lancaster and the Queen’s College designs 9<br />

pronaos, as suggested in PROPOSITION IV; 23 and<br />

the layout of the lateral facades reflects PROPOSI-<br />

TION A, published here for the first time 24 . Within<br />

the old Oxford tradition, can this result be considered<br />

a complete ‘fiasco’?<br />

Soon after creating the Queen’s ‘Propositions,’<br />

Hawksmoor was employed for the Clarendon<br />

Building project by the same William Lancaster<br />

and his colleagues, the Delegates of the Press. 25<br />

From that moment on, he played a central role in<br />

planning an urban and architectural renewal of<br />

Oxford that would have changed the face of the<br />

city forever. 26 With the Queen’s designs,<br />

Hawksmoor had wanted to make himself known to<br />

the man who had more power than anyone else in<br />

Oxford to involve him in new projects. In the end,<br />

the architect accomplished this goal.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

I would like to thank Amanda Saville for her kind<br />

suggestion to write this brief contribution on<br />

Hawksmoor’s Queen’s Designs. She and her staff<br />

have given much valuable help for my research on<br />

Oxford University architecture and its patronage<br />

between 1702 and 1736.<br />

1<br />

This initiative continued the late-seventeenth-century<br />

enlargement of the medieval college, which had included the<br />

creation of the Williamson Building on the northeast side<br />

(1671–1672) and the Library on the northwest side (1692–<br />

1696); followed in 1707 by a north range of which ‘one half of<br />

it’ was ‘at the sole charge of Dr Lancaster […] and the other<br />

half at the common expense of the Society’. Thus, the new<br />

building campaign of 1710 concerned the reconstruction of<br />

the remaing southern parts of College, which would have<br />

faced on High Street. See J. Magrath, The Queen’s College, 2<br />

vols. (Oxford, 1921), II, pp. 63-87; Victoria History of the<br />

County of Oxford, 16 vols., III, The University of Oxford<br />

(London, 1954), pp. 138-142.<br />

2<br />

J. Ayliffe, The ancient and present state of the University of<br />

Oxford (London, 1714), p. 301.<br />

3<br />

See H. Colvin, Unbuilt Oxford (New Haven and London,<br />

1983), p. 47; Nicholas Hawksmoor and the replanning of<br />

Oxford, ed. by R. White (Oxford and London, 1997).<br />

4<br />

K. Downes, Hawksmoor (London [1959] 1979), p. 102.<br />

5<br />

Six are numbered with roman numerals I-VI, and one<br />

labelled with the letter ‘A’. There are also three plans for<br />

alternative designs [Queen’s 14, 15, 17] and two High Street<br />

front elevations [Queen’s 18-20]. In Queen’s Library there is<br />

a manuscript catalogue by Roger White.<br />

6<br />

K. Downes, Hawksmoor, cit., pp. 102-107; H. Colvin,<br />

Unbuilt…, cit., pp. 47-53; G. Worsley, ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor:<br />

A Pioneer Neo-Palladian?’, Architectural History, vol. 33<br />

(1990), pp. 60-74; R. White, Nicholas Hawksmoor…, cit.,<br />

pp. 15-24.<br />

7<br />

K. Downes, Hawksmoor, cit., p. 107.<br />

8<br />

R. White, Nicholas Hawksmoor…, cit., p. 16; see also H.<br />

Colvin, Unbuilt…, cit., p. 47.<br />

9<br />

C. Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus… (London, 1715), pl. 3.<br />

The plate is inscribed to William Lancaster ‘Vicar of St<br />

Martin in the Field [...] Provost of Queens College Oxon’.<br />

10<br />

Remarks and collections of Thomas Hearne, ed. by C. E.<br />

Doble, 11 vols. (Oxford 1885-1921), VII, p. 247.<br />

11<br />

See: Queen’s 3, 4, 12.<br />

12<br />

This corpus includes designs for All Souls College,<br />

Clarendon Building, Radcliffe Library, Brasenose, Worcester,<br />

Magdalen College.<br />

13<br />

K. Downes, Hawksmoor, cit., p. 102.<br />

14<br />

As already pointed out by Kerry Downes, Hawskmoor<br />

appears not to have had either an exact survey of the site or a<br />

master plan to follow as he had, for example, in the case of<br />

the later design for the Clarendon building.<br />

15<br />

See footnote 1.<br />

16<br />

For Clarke’s All Souls master plan see H. Colvin, Unbuilt…,<br />

cit., p. 36.<br />

17<br />

V. Hart, Nicholas Hawksmoor: rebuilding ancient<br />

wonders (New Haven and London, 2002), pp. 202-213, in<br />

particular p. 204.<br />

18<br />

T. Clayton, ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke at<br />

Worcester College Oxford’, Print Quarterly, 9 (1992), pp.<br />

123-141. During the Opler Conference at Worcester College<br />

(29th-31st March <strong>2012</strong>) I gave a paper on Clarke’s library<br />

entitled: Architecture and Oxford University in the early<br />

Eighteenth Century: George Clarke’s ‘Accademia’ and his<br />

library-laboratory.<br />

19<br />

For the arrangement of hall and chapel en pendant see K.<br />

Downes, Hawksmoor, cit., p. 104.<br />

20<br />

For Hawksmoor’s Palladian sources, see G. Worsley,<br />

‘Nicholas Hawksmoor…, cit. .<br />

21<br />

See footnote 20.<br />

22<br />

See G. Worsley, ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor…’, cit., p. 61; R.<br />

White, Nicholas Hawksmoor…, cit., p. 15.<br />

23<br />

See footnote 19.<br />

24<br />

The only part of the College that can be regarded as<br />

Hawksmoor’s work is the main gateway on High Street, built<br />

by W. Townesend in 1733-36.<br />

25<br />

K. Downes, Hawksmoor, cit., pp. 107-109; H. Colvin,<br />

Unbuilt…, cit., pp. 60-64; R. White, Nicholas Hawksmoor…,<br />

cit., pp. 45-48; G. Tyack, ‘The Clarendon Building: Printing<br />

House and Propylaeum’, Bodleian Library Record, 23<br />

(2010), pp. 41-63.<br />

26<br />

Hawksmoor and the Oxford renovatio urbis is the central<br />

subject of my PhD thesis ‘The Seat of the Muses’. Nicholas<br />

Hawksmoor and Oxford (University IUAV of Venice, 2011)<br />

and of my current book-project.<br />

Dr. Eleonora Pistis is Scott Opler Research Fellow<br />

in Architectural History at Worcester College,<br />

Oxford. She has conducted various studies on<br />

eighteenth-century European architecture, with<br />

particular attention to Italy, France and England.<br />

Her current book-project concerns Nicholas<br />

Hawksmoor, George Clarke and the renovatio<br />

urbis of Oxford.

10<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

Heraldic manuscripts in the Library of<br />

The Queen’s College<br />

Nigel Ramsay<br />

University College London<br />

M<br />

any hundreds of heraldic manuscripts<br />

of the Tudor and Stuart<br />

periods are extant today. Most are<br />

without much scholarly value as<br />

texts, being copies that were produced for sale to<br />

the numerous Englishmen who wished simply to<br />

be better informed about the heraldry and family<br />

relationships of their fellow countrymen. They<br />

were valued as reference books, rather like a<br />

Who’s Who today; and they were not the sort of<br />

book that anyone would have expected to find in<br />

an Oxford or Cambridge college library. Heraldic<br />

manuscripts began to enter the colleges’ collections<br />

only in the late seventeenth century, when<br />

the study of English history was itself starting to<br />

be seen as a suitable subject for study by the<br />

colleges’ Fellows.<br />

Original heraldic compilations are much rarer,<br />

and in principle those that were produced in the<br />

course of their official duties by the officers of<br />

arms (the three Kings of Arms, six Heralds of<br />

Arms and four Pursuivants of Arms who together<br />

comprise the College of Arms) became the property<br />

of their College. Almost all the original<br />

records of the visitations of the different counties<br />

of England and Wales that were carried out<br />

between the early sixteenth and late seventeenth<br />

centuries are today at the College of Arms; the<br />

most authoritative list of visitations and their<br />

records is accordingly that of Sir Anthony Wagner,<br />

in his Records and collections of the College of<br />

Arms (London, 1952). When heralds produced<br />

other books, for use in the course of their professional<br />

duties, there was a tendency for these<br />

compilations to be passed on, by gift or sale, to<br />

other officers of arms: open sales in the secondhand<br />

market must have been much less common<br />

than private-treaty sales by, say, heralds’ widows<br />

to practising heralds. There was a professional<br />

wish to keep the heralds’ books out of the hands of<br />

the herald-painters and other interlopers who<br />

posed a commercial threat to the heralds’ own<br />

private practices.<br />

Fig. 1: Drawing by Robert Glover of sealed attached to grant<br />

of the manor of Pesenhall to Roger Bigod, earl of Norfolk, by<br />

Alexander, King of Scotland. (MS 166, folio 2 recto)<br />

The most capable heralds have always tended to<br />

be both writers and compilers themselves as well<br />

as collectors of the works of their predecessors.<br />

Robert Glover, Somerset Herald, who died aged 44<br />

in 1588, was regarded in his own day as the most<br />

scholarly and capable of all the officers of arms;<br />

and he certainly was also the most prolific writer<br />

and transcriber of his age, as well as being a major<br />

collector of medieval and Tudor historical and<br />

heraldic manuscripts.<br />

The College of Arms was in a state of some<br />

disarray in the 1580s, and Glover’s enormous<br />

collection was divided and dispersed within a few<br />

months of his death. A good many of his manuscripts<br />

ultimately passed into the collections of<br />

other heralds—including his nephew John Philipot<br />

(these manuscripts later being acquired by the<br />

College of Arms) and Elias Ashmole (by whom<br />

they were bequeathed to the University of Oxford).<br />

A few were acquired by his near-contemporary<br />

Ralph Brooke (c. 1553-1625), Rouge Croix Pursuivant<br />

from 1580 and York Herald from 1592.<br />

Brooke was an acrimonious and litigious man,<br />

who frequently quarrelled with his fellow-officers<br />

of arms, but he was undoubtedly very capable; and<br />

his abilities extended to his collecting. He acquired<br />

a considerable group of manuscripts that had been<br />

written by Glover, and several of these are today at<br />

Queen’s.<br />

For the medieval historian, the most remarkable<br />

of these manuscripts of Glover’s is MS 166 (fig. 1).<br />

It is one of his books of miscellaneous notes, and<br />

was compiled in the mid to late 1570s. It is replete<br />

with excerpts and transcripts of medieval charters,

Heraldic manuscripts in the Library of The Queen’s College 11<br />

perhaps no more than a decade or two previously;<br />

it was also an opportunity for him to engage in<br />

original research, examining charters that might<br />

provide new material for some of his wider aims,<br />

such as his projected record of all the baronial<br />

families that there had ever been in England.<br />

Fig. 2: Williamson family tree and pasted in coat of arms of<br />

Joseph Williamson from Glover’s Visitation of Northamptonshire.<br />

(MS 112, folio 50 recto)<br />

interspersed with notes of heraldry seen in parish<br />

churches (in Essex, especially), draft funeral<br />

certificates (such as were written by heralds when<br />

they conducted public funerals that incorporated a<br />

display of the deceased’s coat of arms) and<br />

excerpts from medieval texts, such as the names of<br />

benefactors listed in the Almoner’s book of St<br />

Alban’s Abbey. As always with such collections of<br />

notes and transcripts, the direct historical value<br />

lies partly in the presence of copies of documents<br />

that in their original form have since been lost—<br />

although discovering whether the originals may<br />

survive is rarely easy.<br />

For both the Tudor historian and the armorist,<br />

there is obviously enormous value in MS 106, the<br />

record of Glover’s visitation of Staffordshire, 1583.<br />

This is the original manuscript, and lies behind all<br />

other known copies; it is thus our primary authority<br />

for the many genealogies that it provides.<br />

Moreover, it is not just a collection of genealogical<br />

tables (authenticated by the signature of the head<br />

of each armigerous Staffordshire family); like<br />

Glover’s other books of visitation pedigrees, it is<br />

also replete with notes of the ‘proofs’ that he was<br />

shown: medieval charters and their seals, and<br />

other records that he felt to be of value. For<br />

Glover, a heraldic visitation was not just the<br />

occasion for making the official record of changes<br />

to a county’s families since the last visitation, of<br />

The route by which part of Ralph Brooke’s collection<br />

came to Queen’s College is significant. The<br />

College’s heraldic manuscripts seem almost all to<br />

have formed part of the legacy of Sir Joseph<br />

Williamson in 1701 (fig. 2). Williamson was keeper<br />

of the State Paper Office (among many other<br />

public offices), and another part of his heraldic<br />

collection seems to have entered that Office (and<br />

so is today dispersed within the Public Record<br />

Office’s class SP 9, in the National Archives at<br />

Kew). Williamson was fortunate enough to acquire<br />

much or all of the collection of manuscripts of Sir<br />

Thomas Shirley (c. 1590-1654), a country gentleman<br />

who is best known today as having been one<br />

of a group of four antiquaries—Sir Edward Dering,<br />

Sir Christopher Hatton, William Dugdale and<br />

Shirley himself—who in 1638 agreed to pool their<br />

documentary resources, putting all their antiquarian<br />

collections at each other’s disposal. For these<br />

purposes, Shirley’s books were to be marked with<br />

his coat of arms, and this may in part explain why<br />

his manuscripts that are at Queen’s are still<br />

identifiable in this way today. Comparatively little<br />

is known of Shirley’s life. His letters and accounts<br />

appear not to survive, and his intended magnum<br />

opus, entitled The Catholic armorial, remains in<br />

unpublished obscurity within PRO, SP 9; but his<br />

acquisition of a substantial portion of Ralph<br />

Brooke’s library has indirectly ensured its survival<br />

and may one day enable a re-assessment of some<br />

of Shirley’s own activities. No less importantly,<br />

through Ralph Brooke, Sir Thomas Shirley and Sir<br />

Joseph Williamson, a significant group of Robert<br />

Glover’s manuscripts has been kept together and<br />

preserved for scholarly use at Queen’s.<br />

1<br />

Not all, however; for instance, one of Brooke’s Glover<br />

manuscripts is now MS Harley 807 in the British Library.<br />

2<br />

A.R. Wagner, A catalogue of English mediaeval rolls of<br />

arms, Aspilogia I (Oxford, 1950), p. xxii. See also, more<br />

generally, R. Cust, ‘Catholicism, antiquarianism and gentry<br />

honour: the writings of Sir Thomas Shirley’, Midland<br />

History, 23 (1998).<br />

Dr Nigel Ramsay is a Senior Research Associate<br />

engaged on the English Monastic Archives<br />

Project at University College London. He is<br />

shortly to publish an edition of the letters and<br />

papers of Robert Glover.

12<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

Pulsilogium to pulse watch<br />

Denis Gibbs<br />

I<br />

n 1724, when he was aged 75, Sir John<br />

Floyer (1649-1734) gave a collection of<br />

books and unpublished manuscripts to The<br />

Queen’s College, Oxford, where he had<br />

matriculated some sixty years previously. Among<br />

these were a few books he used when he was a<br />

student in Oxford, but the great majority he<br />

acquired during his long and distinguished career<br />

as a physician in the cathedral city of Lichfield. On<br />

blank pages in many of the books and sometimes<br />

on printed pages, Floyer wrote comments, notes<br />

and prescriptions, as well as adding marginal<br />

annotations; his books were for use rather than for<br />

show. Whereas some of the books were used by<br />

him in support of his practice as a physician,<br />

others were acquired to assist him in his research<br />

and writings on medical subjects.<br />

A special feature of the Floyer collection is that it<br />

not only reflects the working library of a busy<br />

provincial physician of the period, but it also<br />

contains much of the source material upon which<br />

Floyer relied when writing his important medical<br />

works. In this respect, the collection provides a<br />

unique resource for the interpretation and understanding<br />

of Sir John Floyer's contributions,<br />

offering continuing opportunities for the further<br />

assessment of his place in the history of medicine,<br />

as well as for more general studies on the nature of<br />

the practice of an important provincial physician<br />

of the time.<br />

Sir John Floyer is acknowledged as an important<br />

pioneer of pulse-timing. He was the first person to<br />

make numerous observations on pulse rates by<br />

means of a specially constructed watch with a<br />

seconds hand 1 . Though Floyer used his pulse<br />

watch within a system of clinical practice that was<br />

still based substantially on Galenic beliefs, the<br />

watch was perhaps the first reasonably efficient<br />

clinical instrument to merit application in practice.<br />

My purpose in this paper is twofold: firstly, to<br />

consider the pulse-watch used by Sir John Floyer<br />

in the context of developments in watch and clock<br />

making of the period; secondly, to draw attention<br />

to the way in which concepts and inventions<br />

relevant to pulse timing were transmitted from<br />

Padua to the small provincial city of Lichfield, in<br />

the late 17 th century.<br />

The pulse watch used by Sir John Floyer was<br />

constructed in 1695 by Samuel Watson. 2 Samuel<br />

Watson (c. 1635-1711) was born in Coventry, a city<br />

noted at the time for the expertise and skill of its<br />

watch and clock makers. Samuel Watson became<br />

prominent among these as a result of which, at<br />

least before 1689 when Watson moved to Long<br />

Acre to continue his craft in London, Floyer had<br />

easy access to one of the leading watch and clock<br />

making masters of the age. Samuel Watson was<br />

one of those who, with his more famous contemporaries<br />

such as Thomas Tompion (1639-1713)<br />

and Daniel Quare (1649-1724), contributed to<br />

improvements which, for some decades, raised<br />

English horological craftsmanship and invention<br />

to a position of pre-eminence. When he moved to<br />

London, Samuel Watson was appointed Mathematician-in-Ordinary<br />

to King Charles II. He was<br />

commissioned (but never paid) by the King to<br />

make a remarkable astronomical clock, now in<br />

Windsor Castle; he was subsequently referred to<br />

as “the curious contriver of the celestial orbitary”.<br />

3,4<br />

Sir John Floyer’s extensive published writings on<br />

pulse timing with the many tables of data he<br />

compiled early in the 18 th century, are well<br />

known. 5 He began by making simple observations<br />

with his pulse watch and soon extended these to<br />

explore possible relationships between pulse rates<br />

and other measurements, such as barometric<br />

pressure and ambient temperature, not to mention<br />

phases of the moon. Though he was sometimes<br />

over ambitious and naïve, particularly when he<br />

extrapolated fancifully from the data he collected,<br />

he did also make important and original discoveries,<br />

such for instance as observing for the first time<br />

an approximate ratio between pulse and respiration<br />

rates.<br />

At a time when Floyer was starting in practice as a<br />

physician in 1675, after he had spent at least 11<br />

years at the University of Oxford, there was a<br />

crucial development in horological technology.<br />

The introduction of a spring balance was conceived<br />

by Robert Hooke (1635-1703), who did<br />

experimental work on the subject as early as 1658.<br />

But, it took another 17 years before Thomas<br />

Tompion, at Hooke’s behest, made a watch for<br />

Charles II in 1675, which was under the control of<br />

a spring balance. Though the watch was neither<br />

very accurate nor reliable, for the first time in<br />

England, the construction of time-pieces to show

Pulsilogium to pulse watch 13<br />

accuracy and reliability were not attainable and,<br />

for some two centuries, watches were used for<br />

show as expensive articles of fashion and jewellery,<br />

rather than as useful time-keepers. It was<br />

only in the late 17 th century that the first reasonably<br />

accurate watches could be made, following the<br />

invention and application of balance springs.<br />

Fig. 1: Title page from Floyer’s The physician’s pulse-watch,<br />

1707. The copy is from Floyer’s library and contains his<br />

handwritten notes. (Sel.f.19)<br />

Fig. 2: Diagram from the second<br />

volume to The physician’s pulsewatch.<br />

(Sel.f.20)<br />

the passing of<br />

seconds as well as<br />

of hours and<br />

minutes, had<br />

become technically<br />

feasible. 6<br />

The importance<br />

of the invention<br />

of the balance<br />

spring needs to be<br />

put briefly into<br />

perspective. The<br />

force of gravity<br />

using a suspended<br />

weight<br />

was the driving<br />

force in long case<br />

clocks. Once<br />

Galileo (1564-<br />

1642) had worked<br />

out that a pendulum<br />

linked to an<br />

escapement<br />

mechanism<br />

would be an ideal<br />

timer at the heart of such a clock, and following<br />

the work of Christiaan Huygens (1639-1696) in<br />

Holland who transformed theory into practice,<br />

long case clocks with hour and minute hands<br />

became fairly precise timekeepers. But they were<br />

large and not readily portable. In the mid-fifteenth<br />

century the force of a mainspring was introduced<br />

as an alternative means of driving clockwork and<br />

this, in turn, led to the birth of watches. Though<br />

ingenious devices like the fusee were added,<br />

In his preface to the first volume of The physician’s<br />

pulse-watch, published in 1707 (fig. 1),<br />

Floyer referred to the instruments he had used for<br />

timing the pulse. “I have for many years tried<br />

pulses by the minute in common watches, and<br />

pendulum clocks, when I was among my patients;<br />

after some time I met with the common seaminute<br />

glass, which I used for my cold bathing,<br />

and by that I made most of my experiments; but<br />

because this was not portable, I caused a pulsewatch<br />

to be made …” Floyer extended his observations<br />

on the pulse and wrote a second volume of<br />

The physician’s pulse-watch which was published<br />

in 1710 (fig. 2). The physician’s pulse-watch was<br />

the only one of the many books he wrote, to be<br />

translated into Italian and published in Venice in<br />

1715. 7 The publication of an Italian edition was an<br />

entirely fitting acknowledgement of the fact that<br />

Italy was the home of the first scientific applications<br />

of pulse-timing, whether by Galileo (1564-<br />

1642), who discovered the isochronism of the<br />

simple pendulum by using his own pulse, or a little<br />

later, by Sanctorius (1561-1636), Professor of<br />

Experimental Medicine in Padua, who extended<br />

Galileo’s observations with the pulsilogium, as<br />

well as proposing the use of other instruments for<br />

measurement in medicine.<br />

Evidence has recently come to light that, in about<br />

1684, Floyer acquired about twenty Renaissance<br />

texts for his own use, which included two books by<br />

Sanctorius. Forty years later, when Floyer was<br />

aged 76, he donated them as part of his collection<br />

of medical books, to the Library of The Queen’s<br />

College, Oxford. Recently, the significance of a<br />

small monogram, AH, written on title pages of<br />

many of the Renaissance books has been discovered.<br />

The ownership device indicated that they<br />

had first belonged to Dr Anthony Hewett (c1603-<br />

1684), who was Floyer’s predecessor as physician<br />

in Lichfield. Very little was then known of Dr<br />

Hewett, but evidence is now available that he<br />

studied medicine at Cambridge and that he<br />

subsequently travelled to Padua, where he was<br />

awarded MD in April 1638. 8 When he returned<br />

from Padua, Hewett brought back books he had<br />

bought while on his Continental travels, and at

14<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

Fig. 3: Title page from<br />

Sanctorius’ Commentary<br />

on Avicenna, 1626,<br />

showing Anthony Hewitt’s<br />

initials at the top of<br />

the page. (HS.b.545)<br />

least some of these were<br />

later acquired by his<br />

successor, Sir John Floyer.<br />

Floyer’s fascination with<br />

measurement in medicine,<br />

especially with timing the<br />

pulse, was inspired by<br />

Sanctorius, particularly<br />

from reading the relevant<br />

parts of Sanctorius’s<br />

Commentary on Avicenna<br />

(1626) (fig. 3), one of the<br />

books he acquired from<br />

Hewett. 9 Here the many<br />

different instruments and<br />

apparatus devised by<br />

Sanctorius, including<br />

several examples of<br />

pulsilogiums, were illustrated<br />

and discussed.<br />

Floyer may well have been as baffled as some<br />

readers of the present day in trying to understand<br />

how several of Sanctorius’s instruments worked;<br />

some were probably prototypes rather than of<br />

proven value, and most were probably designed<br />

with research rather than clinical practice in mind.<br />

Floyer took an important initiative by requesting<br />

Samuel Watson to construct a pulse-watch with a<br />

seconds hand, soon after the requisite technological<br />

advance had been achieved. Sanctorius of<br />

Padua was the pioneer. Floyer followed, seventy<br />

years later, as a disciple of Sanctorius, at a time at<br />

the end of the 17 th century, when easy and reasonably<br />

accurate timing of the pulse using a pocket<br />

watch first became feasible.<br />

1<br />

Morton, Leslie (Garrison and Morton). A Medical bibliography.<br />

3rd ed. London: Deutsch, 1970. 318, item 2670<br />

2<br />

Gibbs, D.D. ‘The physician’s pulse watch.’ Medical History,<br />

1971 15 p. 187-190<br />

3<br />

Lloyd, H. Alan. A collector’s dictionary of clocks. London:<br />

Country Life, 1964.<br />

4<br />

Jagger, C. ‘Royal Clocks.’ Clocks, April 1983 5 p. 35-39<br />

5<br />

Floyer, Sir John The physician’s pulse watch London:<br />

Volume I 1707; Volume II 1710<br />

6<br />

Hayward J.F. English watches. Victoria and Albert<br />

Museum. London: HMSO, 1969.<br />

7<br />

Floyer, Sir John L’oriuolo da polso de medici, ovvero un<br />

saggio per ispiegare l’arte antica di tastare il polso, e per<br />

meglioraria coll’ajuto d’un oriuolo da polso. In tre parti …<br />

Venice: 1715<br />

8<br />

Gibbs, D.D. ‘Dr Anthony Hewett (c. 1603-1684) MD Padua<br />

and Cambridge, Physician of Lichfield and Student of<br />

Renaissance Medicine.’ Staffordshire Studies, in press.<br />

9<br />

Santorio, Santorio (Sanctorius) Commentaria in primam<br />

fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae … Venetiis: Jacobus<br />

Sarcina 1626<br />

Denis Gibbs is a medical historian and one of the<br />

foremost authorities on John Floyer. In his early<br />

career he practiced medicine in Lichfield, Floyer’s<br />

hometown, and later at The Royal London<br />

Hospital. He was educated at Keble College,<br />

Oxford.<br />

Modern swimming instruction begins in<br />

style : the contribution of the influential<br />

Everard Digby (ca. 1551-1605)<br />

Paul Ivanovic<br />

The Queen’s College<br />

E<br />

verard Digby’s De arte natandi<br />

(Sel.b.98) was published in 1587. It is<br />

justifiably credited with being the first<br />

scientific treatise on swimming, at least<br />

in the European sphere. One imagines Digby saw<br />

his work as a useful guide to help prevent and<br />

reduce the deaths of young men in swimming<br />

accidents in Cambridge, where he worked, and<br />

beyond. Although there are a few European<br />

antecedents, these are more in the form of literary<br />

essays celebrating swimming rather than instructive<br />

texts. Outside of Europe, there remains the<br />

possibility of earlier texts in, for example, the<br />

Chinese, Indian or Japanese languages. Indeed, in<br />

Japan interscholastic swimming competitions<br />

have existed since 1603, suggesting that an early<br />

Japanese instructional text may exist, although it<br />

is possible that knowledge was passed down orally<br />

in this and the other traditions.<br />

Digby, an extrovert and perhaps slightly “oddball”<br />

Cambridge scholar, provides a short (115 p.),<br />

coherent and informative narrative, which is<br />

divided into two books. Loosely, the treatise is<br />

structured into a shorter first book with theory<br />

and practical advice, and a longer second book<br />

with illustrative woodcuts outlining swimming<br />

techniques. One presumes Digby provided the<br />

printer with sketches, as it would be impossible to<br />

produce the illustrations from simply consulting<br />

the text. Those of the 43 woodcut illustrations<br />

which show swimming techniques and activities in<br />

the water have been cleverly designed in two parts.

Modern swimming instruction begins in style 15<br />

such as how to carry objects (fig. 2) and keep them<br />

dry and also more eccentrically how to safely pare<br />

your nails in water. The swimming styles are<br />

described rather than named: “to swim like a dog”,<br />

foreshadowing the dog-paddle, and “to swim like a<br />

dolphin”. He essentially covers what we might<br />

recognize as nascent forms of the breaststroke (fig.<br />

3), sidestroke, and backstroke, as well as the<br />

aforementioned dog-paddle.<br />

Fig. 1: Illustration from De<br />

arte natandi showing how<br />

to float in the water.<br />

Fig. 2: Illustration from De<br />

arte natandi showing how to<br />

carry items across water<br />

without getting them wet.<br />

There is an outer background frame – there are 5<br />

used in total – and a smaller changeable internal<br />

woodcut with a naked male swimmer demonstrating<br />

the chosen activity in the water. It is possible<br />

that this rarely used illustrative technique was the<br />

result of necessity, with the cost of so many<br />

completely separate full-page illustrations proving<br />

prohibitively expensive. The idea of a smaller<br />

changeable internal woodcut would therefore<br />

make good sense.<br />

The first book details ideas about swimming; the<br />

health benefits and its nature as a pleasurable<br />

activity. Digby advises on the right time of year to<br />

swim, as May to August, and about the best places<br />

to swim. He also wisely assumes that the value of<br />

swimming to his readers will not be uncontested.<br />

For example, the only four clear references in the<br />

Bible and the many references in Shakespeare to<br />

swimming are invariably negative in nature.<br />

Swimming was also principally engaged in by<br />

people associated with water such as seamen and<br />

bargees, and was not an activity of the elite. One<br />

could count hunting, tournaments and tennis as<br />

elite activities in the 16th century. Nevertheless,<br />

with the Renaissance, and the rediscovery of the<br />

classics, the status of swimming was improving<br />

and it was no longer associated with only lower<br />

class men.<br />

The second book, which illuminates the actual<br />

techniques, may appear unintentionally humorous<br />

to the modern reader. Digby covers getting into<br />

the water (jumping and getting stuck in the mud<br />

could be life threatening), he provides instruction<br />

on how one can swim in different styles, how to<br />

turn in the water and how to float (fig. 1). There<br />

are also a number of ecletic activities included<br />

As the title suggests De arte natandi is in Latin,<br />

and in fact in an elaborate Renaissance Latin,<br />

which would have been accessible only to aristocrats,<br />

clergy and scholars who could read Latin,<br />

thereby significantly limiting the possible audience.<br />

Digby deliberately chose to write in Latin<br />

because he wanted to give swimming a status and<br />

importance, which he felt it lacked. He might have<br />

felt, perhaps slightly humorously, that he was<br />

writing a seminal account of swimming as an “art”<br />

similar to that of Virgil on agriculture or of<br />

Hippocrates and Galen on medicine. However, an<br />

abridged English translation, A short introduction<br />

for to learne to swim by Thomas Middleton,<br />

appeared in 1595. This reused the original plates,<br />

although the background and central plates have<br />

become mixed in certain cases, presumably as a<br />

result of mistakes by the printer, and he hardly<br />

altered the description of the swimming styles.<br />

This testifies to the accuracy of Digby’s account of<br />

swimming during the period. Digby made no claim<br />

to originality as a writer on swimming techniques.<br />

Neither De arte natandi or Middleton’s translation<br />

were reprinted. Middleton’s work seems to<br />

have fallen into obscurity and today there are only<br />

three extant examples, and only one of these<br />

copies, held at the British Library, is complete,<br />

whereas there are more than 10 copies of De arte<br />

natandi. It is unknown how many copies of either<br />

work were originally printed.<br />

Digby’s contribution to the teaching of swimming<br />

continued to be influential<br />

until the 18th century, as a<br />

result of two unacknowledged<br />

English translations. These<br />

are The compleat swimmer<br />

(1658) by William Percey,<br />

and The art of swimming<br />

(1699) by Melchisedech<br />

Thevenot. In the case of<br />

Thevenot, this was the<br />

translation of his own French<br />

work L’art de nager (1696)<br />

plagiarized from Digby.<br />

Fig. 3: Illustration of<br />

the breaststroke from<br />

De arte natandi.

16<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER<br />

Percey’s study is most notable for one of the first<br />

recorded uses of the word “stroke” to describe a<br />

swimming style, otherwise there is little new.<br />

The swimming styles of today essentially evolved<br />

in the late 19th century onwards and would<br />

probably be unrecognizable to 17th century<br />

swimmers. As we are saturated by images of<br />

swimming from cinema and television, it is<br />

difficult to imagine how different swimming styles<br />

might have been in earlier periods. Nevertheless, it<br />

is amusing to note the anachronistic swimming<br />

one finds in historical films, especially in<br />

swashbucklers, though it is true that there is often<br />

surprisingly little swimming in these films. In Sea<br />

devils, set in 1800, Rock Hudson stylishly swims<br />

both a modern looking breaststroke and front<br />

crawl while fully dressed. In fact, most people<br />

would probably have swum in the nude at this<br />

time, costumes being gradually introduced in the<br />

19th century. Another swashbuckler, The crimson<br />

pirate, set in the late 18th century, is a comic<br />

action film which might be considered an antecedent<br />

of Pirates of the Caribbean. There is a scene<br />

in which an entire ship’s crew very competently<br />

swims underwater from one vessel to another,<br />

which they intend to seize. It seems unlikely that<br />

all members of a ship’s crew could swim and<br />

indeed swim very skilfully, and a possible opportunity<br />

for comedy is sadly missed. Indeed, for a very<br />

long time sailors thought it unlucky to learn to<br />

swim. It was not until 1879 that the Queen’s<br />

Regulations for the Royal Navy were amended,<br />

and all seamen were required to take a swim test<br />

or to learn how to swim. In a historical quirk, the<br />

Queen’s Regulations for the British army were<br />

amended earlier in 1868, and swimming instruction<br />

was made a “military duty” for all troops.<br />

Swimming instruction outside of the military<br />

services was for a long time solely provided by<br />

swimming clubs, and was often limited by the lack<br />

of swimming pools. In the 19th century, the<br />

increasing number of swimming pools and the<br />

construction of the railway network provided<br />

opportunities for competition between different<br />

areas and greater access to the sea to swim.<br />

Nevertheless, it was not until 1890 that swimming<br />

instruction in London schools became more<br />

prevalent, with the allocation of education funds<br />

for this purpose. In the provinces, it was over a<br />

decade later before swimming instruction in<br />

schools was to become established.<br />

lose his position at St John’s College, Cambridge<br />

over a minor financial dispute, although there<br />

were also unhelpful underlying religious differences<br />

with his colleagues which also played a part.<br />

He was to support himself as a country clergyman<br />

for the rest of his life. He died in 1605, which was<br />

strangely the same year as a kinsman, Sir Everard<br />

Digby of Stoke Dry, was executed as one of the<br />

main conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot. As a<br />

final note, Nicholas Orme, a key writer on early<br />

English swimming, tried to have a commemorative<br />

postage stamp issued in 1987 on the 400th<br />

anniversary of the publication of De arte natandi,<br />

but sadly he was unsuccessful. One imagines<br />

Everard Digby’s image reflected in the surface, the<br />

mirror suddenly deforming and ripples travelling<br />

outwards before a stillness returns. He remains<br />

another generally uncelebrated British first.<br />

All the English works cited above can be accessed<br />

as full text electronic facsimiles in Early English<br />

Books Online at http://eebo.chadwyck.com.<br />

Bibliography<br />

Capwell Fox, Martha. Swimming. Thomson/Gale, 2003.<br />

Keil, Ian & Don Wix. ‘In the swim: the Amateur Swimming<br />

Association from 1869 to 1994’. Swimming Times, 1996.<br />

Love, Christopher. A social history of swimming in<br />

England, 1800-1918: splashing in the Serpentine. London :<br />

Routledge, 2008.<br />