Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Queen’s College Library<br />

<strong>Insight</strong><br />

Issue 7, Michaelmas Term <strong>2017</strong><br />

New Library Special Issue:<br />

Introduction from Amanda Saville...p.1<br />

‘Queen’s Before Queen’s’ - John Blair...p.2<br />

‘The New Library Project’ - Paul Renton-<br />

Rose...p.6<br />

‘A (Near) Impossible Building’ - Stuart Cade...p.9<br />

‘Reflections on the New Library Project’ - David<br />

Goddard...p. 13

1<br />

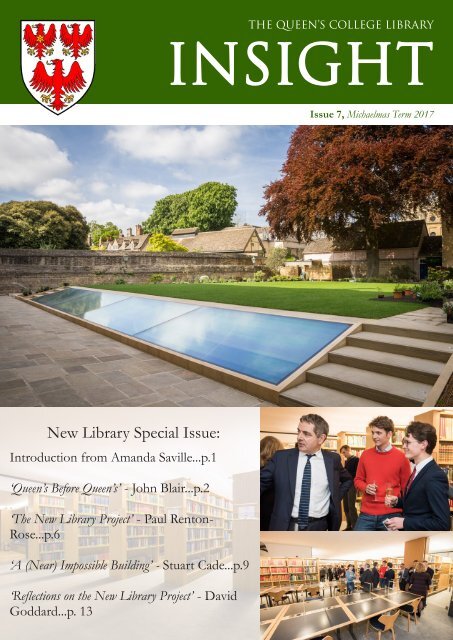

elcome to Issue 7<br />

W of <strong>Insight</strong>. The front<br />

cover of this issue is a<br />

somewhat surreal yet<br />

beautiful image of the roof<br />

light to the New Library<br />

appearing to float between<br />

the terrace and lawn of the<br />

Provost’s Garden. It was<br />

taken in May just as the<br />

garden was being replanted<br />

and shows the<br />

copper beech tree in full<br />

leaf, healthy and happy<br />

after two years of adjacent<br />

construction.<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

The cover gives it away;<br />

this year’s issue, is, as<br />

promised, a “new library<br />

special” and contains<br />

articles that range from an<br />

account of the preconstruction<br />

archaeological dig to an<br />

assessment of all the work<br />

that has been carried out<br />

on the library buildings<br />

over the last four years.<br />

The first article is by John<br />

Blair, Fellow in Modern History, Anglo-Saxon archaeologist,<br />

former Fellow Librarian and one of the earliest supporters in<br />

College for an underground extension to the Library. John<br />

describes in detail the archaeological dig that took place in<br />

early 2015 in the Provost’s Garden, just before the<br />

construction work began. The results of the dig have cast new<br />

light on the expansion of Oxford eastwards from the original<br />

Saxon Burgh and John’s article brings it all to life. Next time<br />

you come to the Library, if you would like to see some of the<br />

finds unearthed during the dig you will find a cross section of<br />

excavated material on display in the new exhibition case in the<br />

Lower Library.<br />

The second article is by Paul Renton-Rose, Project Manager<br />

for Beard Construction, main contractor for the new library.<br />

Paul was in charge of all aspects of the new library build on<br />

site. His article reveals some of the many complexities<br />

involved in constructing such a bespoke building in a site in<br />

the centre of Oxford, surrounded by Grade I listed structures<br />

and with extremely difficult access. Some of the images in<br />

Paul’s article have reminded me just how challenging a<br />

building this was to construct. This can easily be forgotten as I<br />

sit under the roof light in our beautiful new library enjoying<br />

the fruits of the hard work of Paul and so many of his<br />

dedicated and specialist colleagues, who brought the<br />

Architects’ vision to reality so ably.<br />

Paul’s article is followed by a piece by Stuart Cade, one of the<br />

founding partners of MICA Architects, the company which<br />

earlier this year evolved from Rick Mather Architects, the firm<br />

Rowan Atkinson CBE unveiling the commemorative plaque to declare the New Library officially open.<br />

who designed the Library. I have known Stuart for eleven<br />

years and it is a delight to both of us that the building on<br />

which we have worked together for so long, has now come so<br />

spectacularly to life. Stuart’s article describes the design<br />

concepts behind the building and highlights the expertise of<br />

many of the consultants who worked on the project to design<br />

what he describes as “a (near) impossible building”. I would<br />

like to record my thanks both to Stuart and his colleague<br />

Mandy Franz, who, as Project Architect, made the “near<br />

impossible” into a reality.<br />

The final article is a retrospective by David Goddard, Clerk of<br />

Works and College Project Manager for the new library who<br />

looks back at the last four years of intensive work on the<br />

library buildings starting with the refurbishment project of<br />

2013-14 and culminating in the recent opening of our new<br />

library by old member Rowan Atkinson CBE.<br />

I am very grateful to all the contributors who willingly wrote<br />

for me, many of whom had already moved on to manage other<br />

building challenges whilst writing their articles. I am<br />

particularly grateful to my colleague, Sarah Arkle, whose first<br />

issue of <strong>Insight</strong> this is, who has done such a brilliant job in<br />

producing this issue.<br />

If you have ideas for future articles or indeed would like to<br />

contribute, please contact me at<br />

amanda.saville@queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

Amanda Saville, Librarian, November <strong>2017</strong>

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 2<br />

Q U E E N ’ S B E F O R E Q U E E N ’ S : T H E<br />

ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE NEW LIBRARY AND<br />

OXFORD’S ‘EASTERN EXTENSION’<br />

John Blair, The Queen’s College<br />

he new underground library extends deep into the gravel<br />

T subsoil, and its creation involved the removal of all<br />

human deposits. An archaeological excavation – the largest<br />

ever conducted in modern times in the eastern part of the<br />

walled city of Oxford – was therefore required. The layout<br />

and development of this area between the late Anglo-Saxon<br />

period and the twelfth century have been almost completely<br />

obscure, so the exercise promised a glimpse into the unknown.<br />

That promise was fulfilled: what was uncovered was in one<br />

way predictable, in another very surprising.<br />

The excavation was carried out during 2015 by Oxford<br />

Archaeology under the direction of Richard Brown, and is<br />

described in a preliminary report. 1 Post-excavation work<br />

remains to be completed for the final publication, and some<br />

conclusions will probably be modified, but meanwhile Mr<br />

Brown and O.A. have kindly allowed me to set their findings<br />

in context for the benefit of members of Queen’s. Everything<br />

said here is, however, subject to revision in the light of the<br />

final conclusions.<br />

It is generally agreed that Oxford began as a rectilinear<br />

earthwork fort defending an important Thames crossing, and<br />

also enclosing the minster of St Frideswide (now the<br />

Cathedral) established there around the year 700. 2 The placename<br />

first appears on pennies of King Alfred, minted at<br />

Ohsnaforda in the 890s, but it remains unclear whether the first<br />

fort was built by Alfred, by his immediate successors, or even<br />

conceivably by one of his predecessors. The basic topography<br />

of the core area and its rectilinear defences, enclosing a main<br />

crossroads centred on Carfax, is reasonably clear.<br />

There has been considerable debate, however, about the<br />

eastern half of the walled area between Radcliffe Square and<br />

the East Gate, including the site of Queen’s. The northwards<br />

kink in the line of the late medieval city wall between Broad<br />

Street and Holywell has long encouraged the hypothesis that<br />

the eastern zone was an extension, probably added in the late<br />

tenth or eleventh century. That idea appeared to be confirmed<br />

by an excavation between the Old Bodleian and the Clarendon<br />

Building in 1899, which found a sharp southwards curve in the<br />

revetment of the Anglo-Saxon bank: it is difficult to<br />

understand this except as the north-east corner of the primary<br />

fort. 3<br />

On the other hand, a trench against the inner face of the New<br />

College section of the wall in 1993 disclosed an earlier clay<br />

bank, seemingly identical to the primary northern bank that<br />

had been recognised in 1985 behind St Michael’s Street. 4 That<br />

encouraged some re-thinking: could the whole circuit have<br />

been of a single, Alfredian, build after all? 5 In any case, there<br />

were already enough finds and small-scale observations from<br />

the eastern zone to show that late Anglo-Saxon settlement of<br />

some kind existed there, whether intramural or suburban. 6<br />

There were also the more recent excavations within Queen’s<br />

itself, in the Back Quad (2008) and the Nun’s Garden (2010),<br />

each of which had encountered fragmentary late Anglo-Saxon<br />

pits, including in one case a cut halfpenny of Æthelred II<br />

circulating during 997-1003. 7 It was therefore anticipated that<br />

at least some activity from around the year 1000 would be<br />

identified in the Provost’s Garden.<br />

That proved indeed to be the case (Figure 1). The earliest<br />

occupation (Phase 1) comprised three cellars, measuring<br />

respectively 4 x 2.5 m., 2.5 x 2.5 m., and 1.75 x 1 m. To their<br />

south-west were remains of a metalled lane surfaced with<br />

pebbles, marked by wheel-ruts, and a row of post-holes<br />

suggesting some frontage structure between the largest cellar<br />

and the lane. South and west of the cellars were scattered<br />

rubbish-pits, as usual on such sites. Pottery from the pits and<br />

cellars indicated a late Anglo-Saxon date (though the fill of one<br />

of the cellars contained two sherds of Kennet Valley Ware,<br />

introduced c.1050), and there was another Æthelred II coin, of<br />

c.1009-16.<br />

Subsequent developments (Phase 2a), up to the foundation of<br />

Queen’s in 1342, are at present only dated very broadly. A<br />

system of rectilinear boundary ditches cut some of the Phase 1<br />

features, but is also broadly compatible with the settlement<br />

layout of that date, and may have respected the lane. The<br />

abandonment of the lane is indicated by a rubbish-pit cut<br />

through its surface, containing pottery in the range c.1075-<br />

1150. There are apparently no grounds for thinking that the<br />

topographical configuration represented by the cellars and lane<br />

survived beyond the early to mid twelfth century.<br />

Phase 1 is exactly what we would expect of urban or suburban<br />

activity in the range c.980-1050. Cellars (probably contained<br />

within ground-level timber buildings) are the classic buildingform<br />

found in such contexts. Those from the Provost’s<br />

Garden are at the smaller end of the Oxford range, 8<br />

resembling more closely some examples from proto-towns and<br />

monastic centres like Stafford, Northampton and – more<br />

locally – Bampton. 9 To that extent this looks a less `urban’<br />

environment than, for instance, the frontages of Cornmarket<br />

or Queen Street.<br />

The impression that the late Anglo-Saxon activity was<br />

suburban rather than urban in character is strongly reinforced<br />

by the unexpected alignment of the features. Although the lane<br />

survived in a fragmentary state, it unmistakably ran from westnorth-west<br />

to east-south-east; the wheel-ruts in its surface<br />

show that it was a through-route rather than a purely local<br />

feature. The cellars, and the line of stakes on the frontage,<br />

were broadly aligned on the lane. While one should be cautious<br />

about extrapolating from small observations, it is hard to resist<br />

the obvious conclusion that this lane ran from somewhere in<br />

the region of the Clarendon Building and Hertford College<br />

towards the later medieval East Gate on the High Street<br />

(Figure 2).<br />

This looks like a non-urban settlement layout, which at some<br />

stage was scrapped and overlain by the conventionally<br />

rectilinear topography of the eastern walled area. It does not<br />

tell us when the wall around that area was built, but it does

3<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

Figure 1<br />

show that the internal layout did not come to resemble the<br />

rectilinearity of the late Anglo-Saxon core to the west until<br />

after the Norman Conquest. The discovery therefore casts<br />

serious doubt on the hypothesis that the eastern half of the city<br />

was part of the original Alfredian plan, and (setting aside for<br />

the moment the problem of the New College bank) it supports<br />

the earlier view that this was a relatively late extension,<br />

enclosing organic suburban settlement.<br />

The newly-found lane should be seen in relation to Catte Street<br />

(the eastern side of Radcliffe Square), where pre-Conquest<br />

road-metalling of similar appearance was observed in 1980. 10<br />

Together, these lanes now look like a ‘bypass system’, to<br />

channel north-to-south and north-to-east flows of traffic from<br />

the Banbury road down Parks Road, and then around the<br />

outside of the Alfred-period fortress. Whereas Catte Street<br />

presumably led on southwards to a Thames ford, the lane now<br />

discovered under Queen’s would have passed the north-east<br />

corner of the fort and then made for Magdalen Bridge.<br />

When the eastern defences were built (or remodelled as a<br />

continuous circuit), the two lanes would have assumed a new<br />

character as components of the intramural street-plan. Their<br />

northern ends diverged just inside a new gate – Smith Gate –<br />

giving access to the city from Parks Road. Whereas Catte<br />

Street lost its function as a through-route (it was cut short at<br />

Merton Street and then the city wall to the south), the lane<br />

across the Queen’s site would have remained the most direct<br />

route from Smith Gate to the new East Gate. In other words,<br />

it was an earlier incarnation of Queen’s Lane: the present<br />

configuration of sharp-angled bends – so familiar (and at<br />

times so tiresome) to all members of the College – must have<br />

been planned to accommodate blocks of tenements in broad<br />

conformity with the rectilinear layout of the original nucleus<br />

and the extended walls.<br />

When did that happen? Queen’s Lane had assumed its present<br />

configuration by c.1240, when it was known as ‘Thorald the<br />

Tawyer’s Lane’. 11 The replanning must, however, have

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 4<br />

occurred by c.1210 at the latest, since some individual<br />

tenements in the blocks facing the High Street (under the main<br />

front of Queen’s and the shops east of the Lane entrance), 12<br />

and the block facing Catte Street (under Hertford College),<br />

have sets of deeds starting around or just after that date: 13 the<br />

lane must have been diverted before those tenements were laid<br />

out. Oxford has a great wealth of medieval deeds, but<br />

documentation at the level of individual tenements is<br />

essentially post-1200: the fact that the documented properties<br />

were evidently well-established when their deeds start pushes<br />

the replanning episode back into the twelfth century. That is<br />

of course consistent with the excavated evidence that the<br />

original lane was disused, and being cut by pits, no later than<br />

c.1150.<br />

There is a likely connection, though not a necessary one,<br />

between the building of the eastern walls (in their developed<br />

form of a continuous circuit) and the tenemental replanning. It<br />

is in theory quite possible that after the walls were built, the<br />

diagonal lane inside them – now entered at its two ends from<br />

Smith Gate and East Gate – remained in use for decades or<br />

even generations. Alternatively, the walls and the tenementseries<br />

that they enclosed could have been created in a single,<br />

comprehensive town planning exercise. It is normally assumed<br />

that the walls existed at least by the 1080s, but even that is far<br />

from clear. Both in Domesday Book, and in the next<br />

document that mentions it (a charter of 1153-4), the<br />

topographical status of St Peter’s-in-the-East church is left<br />

frustratingly ambiguous : ‘St Peter’s church of Oxford’, rather<br />

than ‘in Oxford’. 14 Even the charter’s description of it as ‘near<br />

the East Gate’ (ecclesia Sancti Petri de Oxenefordia que sita est iuxta<br />

portam de est) is not conclusive, since that might refer either to<br />

the second East Gate (150 metres south-eastwards) or to the<br />

putative original one (250 metres south-westwards).<br />

A different approach to this problem concerns the so-called<br />

‘mural mansions’: the special group of tenements that,<br />

according to Domesday Book, ‘were free in King Edward [the<br />

Confessor]’s time of all customary obligations except armyservice<br />

and repairing the wall’. 15 While the pre-Conquest<br />

origins of the system are thus certain, Hilary Turner’s<br />

topographical analysis in 1990 showed that the ‘mural<br />

mansions’ capable of being located on the ground<br />

concentrated heavily in the north-east part of the developed<br />

city, east of Radcliffe Square and north of High Street. 16 That<br />

cannot reflect late Anglo-Saxon arrangements in any simple or<br />

Figure 2

5<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

direct way, since several of the tenements whose proprietors<br />

were charged with wall-duty in a writ of 1227 must have taken<br />

shape after Queen’s Lane assumed its present dog-legged form.<br />

A more straightforward explanation would be that these<br />

tenements do not relate to the Anglo-Saxon system of wallmaintenance<br />

at all, but rather to a twelfth-century extension of<br />

it. On that view, one might envisage an agreement whereby the<br />

Crown allowed the extended walls to be built, on condition<br />

that the burden of maintaining them was apportioned between<br />

the tenants of the new house-plots that were thus enclosed and<br />

protected.<br />

Perhaps, then, there is something to be said for a new<br />

hypothesis: that the eastern walled circuit in its developed<br />

form, and the planned tenements inside it, were laid out<br />

together at a date not long before the abandonment of the<br />

settlement on the Provost’s Garden site by the 1150s. In Henry<br />

I’s reign Oxford was already recovering from its post-Conquest<br />

depression, and growing fast. 17 Another obvious possibility is<br />

that the Anarchy years of 1139-53 (which despite the political<br />

chaos were an era of strong economic growth. 18 ) created a<br />

compelling incentive to defend the valuable church of St Peter,<br />

and the now densely-settled zone between it and the city wall.<br />

It would have helped that the two powerful magnates with a<br />

direct interest in this part of eastern Oxford and Holywell<br />

manor were Angevin supporters, well-placed at court: Henry<br />

d’Oilly, the heir of Robert d’Oilly who had held St Peter’s<br />

church and Holywell in 1086, and Henry of Oxford, Matilda’s<br />

local henchman, who built a massive Romanesque house in the<br />

west of the city. 19 The 1153-4 charter mentioned above is an<br />

(ultimately ineffectual) grant by Henry d’Oilly to Oseney Abbey<br />

of St Peter’s church, which at that point was firmly in the<br />

clutches of John of Oxford, Henry of Oxford’s son and future<br />

bishop of Norwich. 20 John may well have been responsible for<br />

the sumptuous Romanesque rebuilding of the church that still<br />

largely survives (now St Edmund Hall library), and he certainly<br />

enjoyed a large and apparently complex residence west of St<br />

Peter’s churchyard, occupying what is now the eastern half of<br />

the Back Quad at Queen’s. 21 If the extension of the walls and<br />

the replanning of the area inside them happened in, say, the<br />

1140s, it is almost certain that the two Henrys were involved in<br />

one way or another.<br />

At this point we need to take a step back, and consider the<br />

status and fortunes of St Peter’s church: it may have been the<br />

single most important influence on the urban developments to<br />

its west. Although the early ecclesiastical heart of Oxford was<br />

certainly St Frideswide’s, there is persuasive circumstantial<br />

evidence that St Peter’s-in-the-East was also an Anglo-Saxon<br />

monastic complex, possibly one of a series established on the<br />

peripheries of Mercian centres by King Alfred’s daughter<br />

Æthelflaed. 22 During the tenth to twelfth centuries, it was often<br />

the fate of formerly independent minsters to be annexed as<br />

essentially the private property of secular and ecclesiastical<br />

magnates. Domesday Book (which unfortunately says nothing<br />

here about pre-Conquest arrangements) makes it clear that this<br />

had happened to St Peter’s by 1086: both the church and its<br />

manor of Holywell were controlled by the Norman baron<br />

Robert d’Oilly. 23 Its later twelfth-century status, as the personal<br />

church and residence of a great curial ecclesiastic, looks equally<br />

typical. The absence of early sources should not disguise from<br />

us the former wealth and status of this church, which would<br />

certainly have been surrounded by a substantial precinct and<br />

associated buildings.<br />

We have no evidence for what that complex was like (the<br />

broken circle shown on Figure 2 is purely schematic), but it<br />

could have included a significant part of what would become<br />

the walled extension north of High Street. There are hints of it<br />

in thirteenth-century deeds describing the tenements on the<br />

easternmost part of the Queen’s site: Bishop John’s house<br />

comprising a ‘messuage with houses, orchard(?) and the whole<br />

courtyard … in the churchyard of St Peter’s’ (mesuagium cum<br />

domibus et uirgulto et tota curia … in atrio Beati Petri), and the<br />

tenement to its south ‘in St Peter’s churchyard’. 24 An odd<br />

feature of these descriptions is that they ignore the intervening<br />

Queen’s Lane, which certainly existed when they were written.<br />

The explanation is presumably that they were carried over<br />

from earlier documentation, dating from a time before the<br />

replanning, when St Peter’s and its peripheral structures<br />

dominated the local landscape.<br />

If we take another step backwards, that perspective helps to<br />

set the early eleventh-century occupation in context. If the<br />

Queen’s site was suburban in the sense that it was outside the<br />

eastern rampart of the city, it was also suburban in the sense<br />

that it developed on the periphery of an Anglo-Saxon minster:<br />

many eleventh-century towns began as what an Alfred-period<br />

translator (rendering Bede’s phrase urbana loca into Old<br />

English) called ‘minster-places’. 25 This was therefore a place of<br />

a rather special and unusual kind, arising from the original<br />

placement of St Peter’s some way outside the fort: a suburb, as<br />

it were, twice over. And indeed it offers a classic illustration of<br />

the kind of small-scale cultivation for urban consumption that<br />

underlies so many places of this kind. The Domesday account<br />

of Holywell manor in 1086 mentions 23 men ‘having little<br />

gardens’ (hortulos habentes). 26 Smallholders of this kind, who may<br />

have combined obligations to their lords with marketgardening<br />

and craft production, were very common of the<br />

edges of eleventh-century towns. 27 Maybe some of their wares<br />

were sold from the roadside buildings now identified under the<br />

Provost’s Garden.<br />

Having said all that, there remains the problem – a big and<br />

important one – of the New College bank. The feature<br />

observed in 1993 is scarcely diagnostic physically: a city<br />

defence constructed in the twelfth century would probably still<br />

have been earthen, 28 and it is not obvious that the bank<br />

material of a rampart built in, say, 1150 would look different<br />

from one built in, say, 1000. However, Optically Stimulated<br />

Luminescence (OSL) results just released point to the startling<br />

conclusion that this feature, or parts of it, was constructed in<br />

the eighth century. 29 This remarkable new evidence (for<br />

immediate access to which I am deeply grateful to Ben Ford of<br />

Oxford Archaeology) raises implications that cannot be<br />

considered properly here, let alone answered. Possibly the<br />

eighth-century earthwork was a linear bank – or even a<br />

monastic enclosure around St Peter’s – that survived as a<br />

relict landscape feature to be incorporated into the twelfthcentury<br />

defences. It is hard to see it as an integral part of the

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 6<br />

Alfred-period fort; rather, that must have been built<br />

immediately west of some structure surviving from the period<br />

of Mercian control. At all events, the suburban character of<br />

the occupation around the year 1000 can scarcely be<br />

reconciled with the earthwork being a coherent barrier<br />

between town and countryside at that stage. For the moment<br />

this question must remain unresolved, but debate will certainly<br />

continue.<br />

The Anglo-Saxon landscape of the Queen’s site is very deeply<br />

buried: under the twelfth-century urban replanning, under the<br />

late medieval College buildings, and finally under their<br />

Baroque successors. There is no possibility of exploring it<br />

except by deep excavation, which is why it has remained so<br />

mysterious hitherto. Over the past decade, Queen’s has had<br />

the confidence and courage to augment its facilities with a new<br />

kitchen, lecture-room and library. That has been at the cost of<br />

considerable disruption, now happily behind us. An<br />

unexpected bonus along the way has been a significant<br />

contribution to understanding the origins and early growth of<br />

Oxford.<br />

Notes and references<br />

1. R. Brown, Provost’s Garden, The Queen’s College, Oxford: Post-<br />

Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design (unpublished client<br />

report, Oxford Archaeology, September 2016).<br />

2. J. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire (Stroud, 1994), 52-4, 61-3, 87-92,<br />

146-52; A. Dodd (ed.), Oxford Before the University (Oxford, 2003).<br />

3. Julian Munby in Dodd (ed.), Oxford Before the University, 172-83.<br />

4. Paul Booth in Dodd (ed.), Oxford Before the University, 183-6.<br />

5. Julian Munby in Dodd (ed.), Oxford Before the University, 24-5,<br />

concluding that `the proposed eastern extension remains really<br />

quite difficult to reconcile with the archaeological evidence’.<br />

6. J. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire, 161.<br />

7. A. Norton and J. Mumford, `Anglo-Saxon Pits and a Medieval<br />

Kitchen at The Queen’s College, Oxford’, Oxoniensia, 75 (2010),<br />

165-217, at pp.177-9; S. Teague, A. Norton and A. Dodd, `Late<br />

Saxon, Medieval and Post-Medieval Archaeology at the Nun’s<br />

Garden, The Queen’s College, Oxford’, Oxoniensia, 80 (2015), 143<br />

-85, at pp.147-8.<br />

8. J. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire, 162-4; Dodd, Oxford Before the<br />

University, 35-41.<br />

9. J. Blair, Building Anglo-Saxon England (Princeton, 2018), Fig. 131.<br />

10. Dodd, Oxford Before the University, 260, 397.<br />

11. H.E. Salter, Survey of Oxford, I (Oxford Historical Soc. n.s.14,<br />

1960), 160 (tenement NE 230); Cartulary of Oseney Abbey, ed. H.E.<br />

Salter, I (Oxford Historical Soc. 89, 1929), 269-71<br />

12. Salter, Survey, I, 135-47 (tenements NE 173-95, especially 175,<br />

177, 183, 190 with starting deeds no later than 1210).<br />

13. Salter, Survey, I, 92-8 (tenements NE 131-6, especially 131 with a<br />

starting deed of c.1220).<br />

14. Great Domesday Book fo. 158v; H.E. Salter, Facsimiles of Early<br />

Charters in Oxford Muniment Rooms (Oxford, 1929), No.73.<br />

15. Great Domesday Book fo.154.<br />

16. H.L. Turner, `The Mural Mansions of Oxford: Attempted<br />

Identifications’, Oxoniensia, 55 (1990), 73-9; cf. O. Creighton and<br />

R. Higham, Medieval Town Walls (Stroud, 2005), 39-40, 81, etc.<br />

17. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire, 177.<br />

18. Here I cannot resist recalling that my predecessor, John<br />

Prestwich, made this point very powerfully in a lecture that I<br />

heard as an undergraduate, in about 1974. I hope he would have<br />

relished the thought that urban replanning from the Anarchy<br />

period lies directly under Queen’s.<br />

19. J. Blair, `Frewin Hall, Oxford; a Norman Mansion and a<br />

Monastic College’, Oxoniensia, 43 (1978), 48-99, at pp.49-64.<br />

20. Salter, Facsimiles of Early Charters, No. 73.<br />

21. Salter, Survey, I, 152-3 (tenement NE 208); Cartulary of Oseney, I,<br />

276-9.<br />

22. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire, 112-13.<br />

23. Great Domesday Book fo. 158v.<br />

24. Salter, Survey, I, 152-3 (tenements NE 208-9); Cartulary of Oseney,<br />

I, 276; Cartulary of the Hospital of St John the Baptist, ed. H.E. Salter,<br />

I (Oxford Hist. Soc. 66, 1914), 344.<br />

25. J. Blair, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society (Oxford, 2005), 330-41.<br />

26. Great Domesday Book fo.158v.<br />

27. C. Dyer ,`Towns and Cottages in Eleventh-Century England’, in<br />

H. Mayr-Harting and R.I. Moore (eds.), Studies in Medieval History<br />

Presented to R.H.C. Davis (London, 1985), 91-106; Blair, Church in<br />

Anglo-Saxon Society, 340-1.<br />

28. Cf. Creighton and Higham, Medieval Town Walls, 178-84.<br />

29. Results communicated by Jean-Luc Schwenninger in July <strong>2017</strong>.<br />

Thanks also to David Radford for his help with this and other<br />

sites.<br />

John Blair is a Fellow in History here at The Queen’s College and<br />

Professor of Medieval History and Archaeology. He was appointed to his<br />

present position at Queen’s in 1981. Outside his academic duties, he<br />

maintains a long-standing involvement in practical archaeology, and in the<br />

worlds of building and landscape conservation.<br />

The New Library Project<br />

Paul Renton-Rose, Beard Construction<br />

For Amanda<br />

une 2015 saw the start of the work on site for the new<br />

J<br />

library project, it had taken years of preparations by the<br />

various architects & design teams and now, with the<br />

archaeology complete, it was time to start the excavation. This<br />

transformed the Provost’s Garden into a construction site and<br />

started the engineering process of the New Library. The<br />

design team had set the bar very high with a wall to wall<br />

excavation that had to be executed with great care & precision<br />

to fit the library into the garden area without disturbing the<br />

surrounding 1690’s library building, listed walls, not forgetting<br />

the reportedly 200-year-old wisteria and copper beech tree.<br />

Protection to the west side of the library facade was formed<br />

with a 5.5-metre-high screen made from steel supports, ply<br />

and Monoflex sheeting. The protection of the historic wall on<br />

the south elevation was completed and agreed with all parties<br />

so piling could commence.<br />

A temporary support for the 38-tonne piling machine required<br />

a designed reinforced piling mat of approximately 1000 tonne<br />

of stone, this was imported, constructed and plate tested<br />

before we allowed the piling to proceed. A strong and stable<br />

platform is essential to keeping the rig flat on the ground and<br />

not allow excessive movement in the mast.<br />

Supporting the ground and historic parts of the Grade I listed

7<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

building and associated<br />

Grade II listed walls,<br />

took great skill and<br />

ingenuity on behalf of<br />

the construction team.<br />

The designed secant<br />

piling was located<br />

around the excavation<br />

up against the lines of<br />

the existing structures,<br />

and in one case within<br />

100mm of the library<br />

facade.<br />

Weekly monitoring of<br />

Piling machine<br />

t h e s u r r o u n d i n g<br />

buildings made sure that the ground support measures that had<br />

been put in place were working and could be constantly<br />

adjusted if required.<br />

Monitoring concrete before and after casting<br />

Whilst the New Library piling and excavation were being<br />

executed, the dismantling of the joinery in the Lower Library<br />

took place: labelling, scheduling, photographing all the parts,<br />

careful removal and transferring off site for 15 months into<br />

storage for later inclusion. Trying to keep a low profile in the<br />

back of the College garden with the only access via Queens &<br />

New College Lane was not easy. Trying to ship out soil;<br />

approximately 8861 tonnes of excavated materials and at the<br />

same time bring in 3000 tonnes of concrete and new materials<br />

through the tight<br />

restrictions of the<br />

Lane, was challenging<br />

to say the least. We<br />

restricted the sizes<br />

and width of the<br />

delivery vehicles and<br />

in some cases the<br />

m a t erials b eing<br />

delivered. As a result,<br />

daily monitoring and<br />

cleaning of the lane<br />

by our staff, and<br />

weekly cleaning with<br />

the road sweeper, was<br />

necessary.<br />

The pump used during the build to place concrete<br />

Contractors worked hard over the 18 months to keep<br />

members of the public and tourists safe whilst escorting the<br />

delivery trucks and materials safely to the site, sometimes, with<br />

agreement of all parties and Oxford City Council, in the early<br />

hours of the mornings to reduce the risk to the public and<br />

students.<br />

After extensive archaeology for approximately 3 months by<br />

Oxford Archaeology the site was passed over to us to progress<br />

with the works, during the bulk excavation one of the ground<br />

work team spotted and unearthed an earwax and tooth pick<br />

which was returned to the College for display (approximate<br />

length 10cm).<br />

The finds liaison officer dated this to 13th-15th (medieval)<br />

which would correspond to the early arrangement for The<br />

Queens College (before the wholesale rebuilding of the<br />

17th/18th) when this area seems likely to have been used as a<br />

quarry for building materials; pits for toilets; and the dumping<br />

of rubbish. The artefact, an expensive item for the time, was a<br />

personal grooming item likely to have been accidentally<br />

dropped down the toilet by a student or scholar.<br />

Toothpick/earwax implement found during the excavation<br />

With the type of reinforced concrete structure proposed, most<br />

buildings are built to a B.S. or E.N. (British or European<br />

standards) for location and verticality, in all instances the<br />

structures have exceeded this quality standard allowing the<br />

design team certainty in their design.<br />

Every reinforcement bar was engineered, designed, drawn,<br />

scheduled, delivered to site, cut, bent and then positioned by<br />

hand. Each was measured to fit its correct location to carry out<br />

the job it is required to do. 138 tonnes of steel reinforcement<br />

has been placed by hand (as shown in the photo below) by<br />

experienced skilled workers.<br />

Escorted deliveries along Queen’s lane to the<br />

construction site<br />

Our great band of<br />

banksmen from Curtis

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 8<br />

Interesting Statistics for the Project<br />

299 concrete piles were used to support the ground &<br />

structure of the new building. They also anchor the library<br />

in place; pile length of 3000 metres (3km) if positioned end<br />

to end.<br />

There are 10 ground source piles which extend 50 metres<br />

below the building basement level.<br />

8861 tonnes of excavated soil was removed.<br />

2000 cubic metres of concrete was delivered and pumped<br />

into the ground (approximately 5000 tonnes).<br />

138 tonnes of reinforcement strengthens the concrete<br />

which supports the library structure.<br />

94,338.5 hours have been employed on site by the various<br />

trades (this excludes the production time of offsite<br />

manufacture and work by office or design staff).<br />

9km of electrical wiring was used.<br />

60 separate contractors have had an input to the works on<br />

site, many of them have a specialist knowledge for a<br />

particular part of the build.<br />

737 site personnel & visitors have been inducted and<br />

managed on site.<br />

The location of the site mid way along Queens Lane required a<br />

smaller than normal concrete truck which could deliver the<br />

concrete directly to the site along the very narrow road and<br />

around the tight corners in the lane. Our happy band of lads<br />

on the logistics team escorted the concrete trucks to and from<br />

the site daily ensuring the safety of the public and monitoring<br />

the vehicles passing safely through the historic lane. This<br />

amounted to over 2000 vehicle movements.<br />

Small concrete lorry escorted to and from the site<br />

Creating the ground-level main entrance to the New Library<br />

brought many challenges: working inside the historic Grade I<br />

listed building in a working library; making sure the vital<br />

services of the library were not disturbed, and, ensuring all of<br />

the designed construction fitted into the space required; lift,<br />

staircase and final finishes. It was one area of the build that<br />

had all the makings of a big problem, and could have all gone<br />

terribly wrong. However, it had been planned and designed<br />

well, the design fitted like a glove, millimetre precision in fact,<br />

no second chances.<br />

Positioning the 7-tonne piling rig into the building through the<br />

listed structure onto the timber floors was a concern to<br />

Contractors Design Services, our temporary works engineer,<br />

but with an engineered solution to strengthen the floors we<br />

quickly overcame the issue, and the piling rig operated easily to<br />

form the temporary piles and the permanent piles. The<br />

entrance in the Lower Library was hand excavated (about 450<br />

cubic metres) around the piles and support structure, with the<br />

new structure in place the temporary works were removed and<br />

temporary piles disposed of. Great care was taken throughout<br />

not to create too much disruption or disturbance to the<br />

College by the groundwork team.<br />

The Lower Library panelling was removed in order to install the new<br />

sliding glass door<br />

Reinstatement of the lower<br />

library panelling and<br />

bookcases, which arrived<br />

back from the Botley Road<br />

storage depot piece by<br />

piece, was carried out<br />

lovingly by the Cliveden<br />

conservation team of<br />

carpenters. The Lower<br />

Library panelling was<br />

refurbished, refinished and<br />

polished to match the<br />

existing panelling. Finally,<br />

the new glass sliding door<br />

was installed behind the<br />

panelling.<br />

The design for this project<br />

aimed to limit the visual Work by Cliveden Conservation to<br />

aspect of a complex reinstall the Lower Library Panelling<br />

mechanical and electrical design by concealing as much of the<br />

ventilation and electrical systems within the structure of the<br />

building. Under the raised flooring is the supply air ducting<br />

and the majority of the electrical services which are supported<br />

on hand crafted cable trays and baskets.<br />

What lies beneath: example of the cable tray and basket used underneath<br />

the flooring to conceal complex systems used in the build

9<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

The new library has 10<br />

bore holes for the<br />

ground source heat<br />

pump (GSHP) which<br />

extends down under<br />

the building by 50<br />

metres. It uses the<br />

stable underground<br />

temperature of the<br />

earth to heat and cool<br />

the building. They<br />

Ground source pipework<br />

achieve this by connecting the building and the earth via a<br />

network of underground pipes. These pipes use water to<br />

transfer heat from the earth to the building heat pumps to heat<br />

it and from the building to the earth to cool it.<br />

Ground source heat pumps are a lot more energy efficient and<br />

cost effective than traditional heating systems found in most<br />

homes and buildings. This is because although they only need a<br />

small amount of electricity to run, heat pump systems don’t<br />

burn any kind of fuel on site to produce their heat and use only<br />

the natural temperature of the earth as an energy generating<br />

method. This offers significant reductions in energy bills and<br />

CO2.<br />

Although not visible to the students, the plant room is very<br />

compact; hiding most of the mechanical & electrical services<br />

required to run the complex ventilation and power systems for<br />

the building. Having been very carefully designed and<br />

engineered by the design team the professional team of skilled<br />

craftsmen had to ensure all items fitted into their correct spaces<br />

and the systems all worked together.<br />

both men & women, who have put their heart and soul into<br />

their work every day for the last 20 months ensuring the<br />

project is finished to the highest quality which you can see<br />

today – it has been more than just another job; real people<br />

make things happen.<br />

I would like to list all the men and women on site who played<br />

their part in making this scheme a success but the list would be<br />

very long; 60 contractors have had an input to the works on<br />

site and some of them have had a very specialist input.<br />

There have been lighter moments in the project, New College<br />

Lane was closed for a week during the filming of ‘The<br />

Mummy’ <strong>2017</strong> (Tom Cruise). Careful planning on site and<br />

good liaison with the film location crew meant this did not<br />

stop the works or prevent materials reaching the site.<br />

Images from the set of The Mummy in New College Lane<br />

All projects rely on a team effort which, when working<br />

correctly, provides for a better product. I believe we have had<br />

a brilliant team of people working on the project, both on site<br />

& off site supporting the various functions of the build<br />

process. I would like to thank everyone involved for a job well<br />

done.<br />

I trust the College and students will value and enjoy the space<br />

created for many years to come.<br />

Paul Renton-Rose is a Project Manager for Beard Construction. His job<br />

role is to manage the construction process and liaise with clients,<br />

stakeholders, suppliers and to ensure Beard have the resources in place to<br />

complete the project safely and to a good standard. He says of his career,<br />

after 44 years in industry “I still find construction amazing… how did<br />

they build those pyramids?”<br />

Pipework in the Plant Room<br />

The safety systems installed are ready to be used should the<br />

need arise; these include an aspirating fire detection system,<br />

water misting fire suppression system, gas suppression to the<br />

Historic Collections Archive Store and plant room, emergency<br />

lighting and battery backup.<br />

This plant room has been the most compact and complex<br />

system I have been involved with, as most of the services are<br />

inter-linked and connect to the internet, they are also linked<br />

and monitored by the College Building Management System<br />

(CBMS).<br />

People make buildings, not machines. It is easy to forget about<br />

the many talented, professional, skilled workers and craftsmen,<br />

“A Near Impossible building” -<br />

designing and building the new<br />

library at Queen’s College<br />

Stuart Cade, Rick Mather Architects and MICA<br />

Prologue<br />

he team at Rick Mather Architects (RMA) are delighted<br />

T to see the opening of the New Library, which was<br />

completed earlier this year in time for a busy Trinity Term. As<br />

we often find, the transition from building site to occupied<br />

building has been rapid and it is great to see the new spaces<br />

immediately popular with the hardworking students of<br />

Queen’s.

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 10<br />

We last wrote for <strong>Insight</strong> in 2015 at the outset of the<br />

archaeological and enabling works prior to the<br />

commencement of the main building contract. The subsequent<br />

two years have seen the completion of this preliminary work,<br />

the completion of the new building and, lastly, the reworking<br />

of the existing Lower Library. At time of writing the remainder<br />

of the collections were being moved into the new spaces and<br />

the entire build is now fully operational.<br />

Looking back, RMA commenced work on a scheme for The<br />

Queen’s College Library project in 2006 following a two-stage<br />

design competition. Our work has included detailed designs<br />

f o r b o t h t h e<br />

refurbishment of the<br />

Upper and Lower<br />

Library (completed in<br />

2013); designs for the<br />

large subterranean<br />

extension that is the<br />

New Library and<br />

alterations to the<br />

Lower Library. The<br />

latter has allowed us to<br />

create a generous new<br />

entrance space, and<br />

install a bespoke lift,<br />

which connects the An early design concept montage<br />

new and old buildings.<br />

In the 40-year history of Rick Mather Architects, the project,<br />

one of the last that Rick worked on, is one of our most<br />

significant. For the office it is significant in terms of the<br />

challenge posed by the site: its rich and ancient history; the<br />

precious medieval walls; the Grade 1 listed Library it adjoins<br />

and the magnificent buildings that it extends.<br />

The project is also significant in terms of what it achieves;<br />

extending a landlocked Library where all possible contiguous<br />

(and otherwise) extensions had been considered and found<br />

unfeasible. Furthermore, realizing a scheme that works on<br />

paper is a further challenge in practice. Given the logistical,<br />

planning, archaeological, heritage and physical parameters the<br />

large team feel that the project has built a (near) impossible<br />

building.<br />

The design<br />

The new building and its connection to the existing 1692<br />

Library is a bespoke building in all regards.<br />

The construction has employed 21st Century technologies<br />

allied with traditional trades and crafts to create a crisp and<br />

simple contemporary design and the conservation of historic<br />

spaces; equally marrying large-format, frameless glass with rich<br />

tailor-made oak carpentry.<br />

The designs include a new ground floor entrance; a reworked<br />

Lower Library and a new 8000sq/ft. below-ground extension<br />

containing vital new facilities. The Library extension contains<br />

extensive storage and plant facilities in the western half and a<br />

new reading room and office in the eastern half where all<br />

spaces are bathed in natural light. The effective use of every<br />

millimetre was carefully considered and the building was<br />

planned to maximize use of all walls and corners. In total the<br />

design creates 18 new distinct ‘spaces’ for the Library and<br />

associated Archive. In summary, the project has provided:<br />

A new Reading Room<br />

The reading room is the major new addition to the library. The<br />

r o o m<br />

provides a<br />

light and open<br />

space for 36<br />

users. It is top<br />

lit by a large<br />

new roof<br />

light, which<br />

emits natural<br />

light into the<br />

new building<br />

w h i l s t<br />

a f f o r d i n g<br />

The new reading room<br />

views to the west elevation of the existing Library. Space is<br />

maximized with shelving fitted against all walls. The Reading<br />

Room also gives access to two extensive areas of open book<br />

storage. Firstly, the open shelves; these flank the Reading<br />

Room and entrance and house half of the main circulating<br />

collection. They are configured to guide visitors through the<br />

new spaces; the shelves tapering to open the vista to the<br />

Reading Room. Secondly, and adjoining the Reading Room on<br />

the north and east side, are two linear spaces of roller racking<br />

to maximize storage and house the library’s reserve collections.<br />

Historic Collections and Archive Store<br />

Deep within<br />

t h e n e w<br />

building is the<br />

H i s t o r i c<br />

C o l l e c t i o n s<br />

and Archive<br />

Store, which<br />

provides space<br />

f o r t h e<br />

c o l l e g e ’ s<br />

s i g n i f i c a n t<br />

a n t i q u a r i a n<br />

collection in a<br />

secure and<br />

temperature<br />

c o n t r o l l e d<br />

environment.<br />

The design of<br />

the space<br />

c o m b i n e s<br />

Some of the historic collections in the new HCAS<br />

p r a c t i c a l i t y<br />

and aesthetics;<br />

maximizing storage but with a clean, simple look in deliberate<br />

contrast to the rich material it houses. The HCAS is provided<br />

with its own secure Reading Room; the Feinberg Room which<br />

borrows light from the large main roof light and has space for<br />

up to 4 Special Collections Readers to use simultaneously.

11<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

A new Peet Library of Egyptology<br />

A separate study room for the College’s Egyptology collection<br />

is located in front of the entry gates to the new reading room<br />

so as to be accessible to non-Queen’s members. The Peet has 4<br />

central reader spaces and a large study table. The walls are lined<br />

entirely with bookshelves to maximize space for this important<br />

collection. At the entrance, a glass screen is provided by a<br />

double-sided display case allowing Egyptian artefacts to be<br />

displayed in the round; visible to all Library visitors.<br />

A new multi-purpose space<br />

In the southwest corner a new space is provided for up to 15<br />

students for group study; small seminars and teaching for the<br />

wider College. The space has a sophisticated AV fit-out to<br />

enable it to support a variety of uses.<br />

Lower Library<br />

The Lower Library<br />

h a s b e e n<br />

sensitively returned<br />

to its original<br />

arrangement, as<br />

conceived by C. R.<br />

Cockerell in 1845,<br />

through careful<br />

e d i t i n g a n d<br />

removal of a series<br />

of later additions.<br />

The extra space in<br />

the new building<br />

Newly reconfigured Lower Library<br />

has allowed the<br />

aisles to be cleared of added shelves. Removing the<br />

overcrowded office and other late additions has returned the<br />

entrance space to its intended grandeur. East and West aisles<br />

are opened and provided with new seats and lockers and the<br />

cross aisle is open providing a view from the new Provost’s<br />

Garden to Back Quad. The Lower Library now has 22 high<br />

quality individual reader spaces and 8 new standing desks.<br />

A new entrance<br />

The Lower Library works also include a new entrance where<br />

the existing rehung oak doors have been paired with a new<br />

frameless glass sliding door. This new door provides both an<br />

environmental and<br />

security barrier for the<br />

Library, whilst also<br />

giving a spectacular view<br />

from the north end of<br />

the library to the<br />

southern end of<br />

Hawksmoor’s Front<br />

Quad.<br />

The new entrance to the library<br />

The entrance vestibule<br />

also provides a new lift<br />

linking both existing and<br />

new buildings and<br />

ensuring accessibility to<br />

t h e u n d e r g r o u n d<br />

extension.<br />

A responsible design<br />

The building employs advanced environmental design. 50m<br />

piles transfer thermal energy from deep below the building to<br />

the new air handling and heating/cooling coils in the plant<br />

room. This technology works both to pre-heat the building’s<br />

heating systems in the winter and vice-versa in summer using<br />

the known thermal stability of deep ground temperatures. The<br />

low energy strategy provides for both the new underground<br />

building and now also provides heating and cooling for both<br />

levels of the existing Library.<br />

The building further minimizes energy consumption by use of<br />

its physical location in the ground and maximizes the heat-sink<br />

qualities of its concrete structure – the space was exceptionally<br />

cool even in the June and July heatwave.<br />

The new building uses a single, efficient Menerga air handling<br />

unit which uses adiabatic technology (water) as a cooling<br />

medium and in-turn requires less energy to heat or cool. The<br />

unit similarly recycles and exchanges waste energy at a higher<br />

rate than conventional systems. Electrical energy consumption<br />

is minimized with responsive systems and LED lighting<br />

controlled by a new Building Management System.<br />

Finally, consideration of embodied energy was central to our<br />

material selection with 92% materials (stone, timber, soil and<br />

concrete) sourced within 50 miles of the site. In the case of the<br />

new garden, reused and recycled stone from the existing<br />

garden could be used again for the new terraces and paths.<br />

A new garden<br />

The underground library is topped with a new Provost’s<br />

Garden, bounded by two listed mediaeval stone walls, the<br />

existing library and the Provost’s Lodgings. The new design<br />

for the garden responds to the needs of the Provost (and their<br />

family) and the College - balancing privacy and flexibility –<br />

whilst recreating a serene and verdant garden.<br />

Aerial view of the new Provost’s garden<br />

We worked closely with Landscape Architect Jeremy Rye to<br />

devise a scheme that worked for all and could work effectively<br />

as a ‘roof garden’. The garden is a complex geometry of subtle<br />

slopes and gradients to provide the appearance and utility of a<br />

‘flat’ lawn whilst mediating between many different levels. The<br />

geometry also disguises the new roof light from the east end of

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 12<br />

the garden and the new private lodgings from the west<br />

(Library) end. Most importantly, the new roof light and all<br />

interventions are invisible in the long view to the west<br />

elevation and statues of the existing Library.<br />

Queen’s with a number of opportunities to reconfigure and<br />

extend for future use.<br />

The build<br />

Construction of the new building commenced in spring 2015<br />

and ran for 89 weeks through two kind winters completing in<br />

spring <strong>2017</strong>.<br />

The main contractor, Beard, are a very experienced and skilled<br />

local company with a great deal of experience working in<br />

collegiate Oxford – and specifically at Queen’s, having<br />

completed the kitchen project in 2009. Their expertise and<br />

familiarity assisted in the two major challenges of the build:<br />

getting material to and from the site and digging a large hole<br />

that was both very close to and beneath existing historic listed<br />

structures.<br />

View of the new garden from the Provost’s Lodgings—looking toward the<br />

library<br />

The garden provides two terraces, a circuit of paths and a<br />

variety of new beds and space for a vegetable garden and new<br />

garden store. The paths and ramps make all areas of the<br />

garden accessible to wheelchair users. The below ground<br />

structure and overall garden design has been carefully<br />

configured to safeguard the existing magnificent copper beech<br />

tree which has been carefully protected throughout and we are<br />

pleased to say is prospering in its new setting.<br />

The challenge of building close to existing structures involved<br />

much careful design<br />

work, as well as<br />

buildability studies<br />

being carried out by<br />

the design team<br />

before the project got<br />

to site. Regular<br />

movement checking<br />

was completed in<br />

advance of going on<br />

site to ensure no<br />

damaging movement<br />

of the existing walls,<br />

Library or Lodgings<br />

was taking place.<br />

The forming of the<br />

piles and internal<br />

concrete box was a<br />

careful and steady<br />

process of piling, The new basement level in its early stages<br />

digging, supporting,<br />

backfilling, bracing and finally - with the lid - forming a rigid<br />

waterproof concrete box. The careful iterative process of<br />

building in-the-ground was particularly acute in forming the<br />

link between the new building and Lower Library, where a<br />

bespoke design was used to tunnel beneath the existing<br />

Library footings forming a new basement 5m below the<br />

functioning Library.<br />

Aerial view of the construction site where the garden was replanted<br />

Fitting out the building<br />

Choosing fixtures and fittings for a building is always an added<br />

pleasure for architects and we have greatly enjoyed being<br />

involved in designing the tables, insignias, manifestations, and<br />

fixed furniture together with selecting the new reading chairs,<br />

and other details.<br />

Elsewhere<br />

Benefitting the wider College, the project frees-up 4500sqft for<br />

reuse. Liberated spaces include an extensive basement and<br />

above ground spaces on Front and Back Quad providing<br />

The waterproof box was completed with the installation of 4<br />

super-sized frameless glass roof lights along the eastern edge.<br />

These enormous pieces were carefully manoeuvered into place<br />

by a number of cranes and small lifting machines in early <strong>2017</strong><br />

to finally seal the new building.<br />

The fit-out of the building was no less complex than the<br />

structural works with extensive special fittings to be concealed<br />

and accommodated. The invisibility of air-conditioning,<br />

heating and other services is the result of careful coordination<br />

between joinery and environmental design where the new<br />

shelving often straddles low-level ducts, and grilles. At the top<br />

of shelves, extract ventilation occurs together with much of

13<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

the lighting for the building.<br />

Bespoke shelving lines the walls of every space and is tailored<br />

to provide everything from shelf space, displays, signage and<br />

space for oversized parts of the collection.<br />

Architect, we worked with on the designs for the new<br />

Provost’s Garden.<br />

The new carpentry was also carefully coordinated with a large<br />

number of glazed screens, which are a major feature of the<br />

interior; dividing rooms and enclosing the new lift. Careful<br />

detailing and handling of glass ensured that large panels could<br />

be used and the overall effect of a reflective internal glass ‘face’<br />

in the entrance was able to be maintained.<br />

The finer finishing touches include acoustic ceilings; fabric<br />

wrapped panels; the installation of display cases and exquisite<br />

timber paneling in the Lower Library by Cliveden<br />

Conservation.<br />

In statistics:<br />

The project sank 299 concrete bearing and retaining piles<br />

each 30m long.<br />

We augured 10 special thermal piles each extending 50m<br />

into Oxford clay.<br />

On completion of the piled perimeter 8900 cubic metres of<br />

soil and gravel was excavated for reuse elsewhere.<br />

There are 5km of electrical, AV and data cabling, and 800<br />

linear metres of new shelving.<br />

Epilogue<br />

Having now seen the project realised, we are pleased that many<br />

key aspects of the original concept and design have worked as<br />

intended. Creating a bright day lit new library space was central<br />

to the aims of the design project, and many studies were carried<br />

out at all stages to test this. The roof light aperture, roof slope<br />

and height were all iteratively adjusted to ensure that light<br />

penetrated the new space(s) in the most effective way possible.<br />

The ultimate objective being to provide a comfortable space<br />

that belied its below-ground position. Similarly, we are pleased<br />

that the new Library is invisible from many views – an unusual<br />

objective for architects. The invisibility has been aided by the<br />

planting of the garden which has been established and was in<br />

use this summer.<br />

We are conscious that the project was disruptive for both<br />

College and its neighbours. Whilst a great deal was done to<br />

mitigate this, major projects are always noisy. Considering the<br />

scale of the project, many have remarked that Beard’s excellent<br />

management minimized disruption in a significant way.<br />

We would like to thank the design team of specialist<br />

consultants that we have employed to complete the project.<br />

Eckersley O’Callaghan, our structural and civil engineers,<br />

engineered a complex invisible ‘box’. Atelier Ten, our service<br />

engineers, who devised a sophisticated and effective low energy<br />

strategy (in addition to designing a most beautiful and compact<br />

plant room!)<br />

The full team also included a skilled Acoustician (Sandy Brown<br />

Associates); Fire Consultant (Simon Ham); Planning<br />

Consultant (Nik Lyzba); Health and Safety Consultant<br />

(Gardiner and Theobald) and Jeremy Rye who, as Landscape<br />

The ‘beautiful and compact’ plant room designed by Atelier Ten<br />

Working for Queen’s has been both professional, and a<br />

pleasure in all aspects. The College is an experienced ‘building’<br />

College and its representatives understand the complexities<br />

and nuances of construction and its processes. We would like<br />

to thank Becky Beasley and Angus Bowie for their pivotal role<br />

in the project happening and for leading the internal<br />

consultation process; particularly over the last 4 years. This<br />

project is Amanda Saville’s third new library (her best so far)<br />

and the project has been very fortunate to have her experience<br />

and expertise. Collectively, the College and client team led by<br />

David Goddard have provided experience and fostered<br />

collaboration with all parties, providing a constant presence<br />

while the project was on site; all with calmness and good<br />

humour.<br />

Finally, and particularly at this point, we recognise the privilege<br />

as architects of completing a new building for Queen’s, adding<br />

to a magnificent range of historic buildings and gardens. It is<br />

equally a privilege to add to the College’s much-loved and well<br />

used Library and to see it well prepared for the future.<br />

Stuart Cade is a founding partner of MICA Architects and a<br />

longstanding partner at RMA. Stuart has worked in Oxford for 20<br />

years and has led the practice’s 14 completed projects in Oxford including<br />

work on Oxford’s own Ashmolean Museum. Stuart is currently leading<br />

MICA’s major new commission at Jesus College, in central Oxford.<br />

Reflections on the new library<br />

project<br />

David Goddard, Project Manager<br />

The completion of the New Library marks the end of a four<br />

year programme of intensive redevelopment of our library<br />

facilities. The new underground library construction was the<br />

final phase of work which included the complete overhaul and

Michaelmas <strong>2017</strong> 14<br />

refurbishment of both the existing Upper and Lower Library<br />

spaces. The culmination of this period of work has also aptly<br />

coincided with the 675 th Anniversary of the Foundation of The<br />

Queen’s College.<br />

reader spaces were occupied, along with those in the existing<br />

Upper and Lower libraries. To me this clearly demonstrated<br />

that not only were the additional spaces necessary, but that the<br />

effort, time and energy the College invested in this project had<br />

been entirely worthwhile.<br />

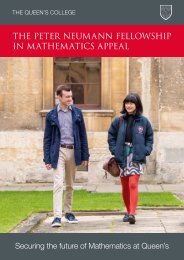

From this: the construction site in early stages...<br />

The work undertaken was comprehensive, and provided the<br />

opportunity to explore, review and develop each and every<br />

aspect of this facility to ensure that the maximum potential<br />

could be achieved from such a valuable College asset. I am<br />

confident that, following completion of this extended and<br />

complex period of work, Queen’s can rightfully be proud of<br />

having one of the finest library buildings within the University.<br />

It is rare that the opportunity arises to become involved in<br />

such a prestigious project and all the more so when it involves<br />

working within, and alongside, such important Grade I listed<br />

buildings. In addition, the area of works was located in the<br />

footprint of a space that was previously occupied by a very<br />

precious garden. I consider myself fortunate that the College<br />

had the faith to entrust me with the responsibility of being The<br />

Project Client Manager. This role not only enabled me to have<br />

influence over the decision making processes, regarding design<br />

changes but also allowed me to ensure satisfactory<br />

coordination between all stakeholders and for overseeing an<br />

appropriate standard of quality control.<br />

The responsibility was particularly testing as in addition to<br />

such a complex project brief, careful thought had to be<br />

afforded to the site logistics. These included very complex and<br />

challenging access constraints and the need to minimise the<br />

detrimental impact on academic life both within Queen’s and<br />

the four neighbouring colleges.<br />

These challenges were eased considerably by the<br />

understanding, cooperation and sacrifice shown by everyone in<br />

College, and in particular the current Junior Members who<br />

gave such selfless support to the cause even though many<br />

would not get to enjoy the benefits of the completed library. I<br />

feel it only right to take this opportunity to sincerely thank<br />

everyone who played a part, no matter how small.<br />

As you are aware the New Library was completed for the<br />

beginning of Trinity Term <strong>2017</strong> and it was very rewarding to<br />

observe that within a short time of it’s opening, all the new<br />

To this: A view into the underground extension to the library<br />

In conclusion, despite the significant challenge that the library<br />

refurbishment programme and new building project have<br />

posed to the College for a number of years, it is reassuring to<br />

witness the successful completion, and we can now look<br />

forward to addressing some of the other areas in College that<br />

require investment and development.<br />

David Goddard is the Clerk of Works here at Queen’s College. He is<br />

responsible for all aspects of building maintenance. He leads a team that<br />

ensures the College is kept in working order whilst being sensitive to the<br />

nature and appearance of the Grade I and Grade II listed buildings<br />

The Queen’s College Library <strong>Insight</strong><br />

Published by The Library, The Queen’s College,<br />

Oxford, OX1 4AW<br />

Copyright The Queen’s College, Oxford, <strong>2017</strong><br />

All rights reserved<br />

ISSN 2049-8349

15<br />

THE QUEEN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY INSIGHT<br />

Liquid Legacies<br />

Beer and Brewing at<br />

The Queen’s College<br />

June<br />

to<br />

Winter<br />

<strong>2017</strong><br />

This small exhibition<br />

is located in the<br />

display cases in the<br />

Queen’s College<br />

Upper Library.<br />

Non-members of the<br />

College, please<br />

contact us in advance<br />

to arrange an<br />

appointment.<br />

01865 279130<br />

library@queens.ox.ac.uk<br />

The Queen’s College Chancellor Ale<br />

‘Some may question its flavour, but none its potency’<br />

J.M. Kaye, The Queen’s College Record, 1936