You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<br />

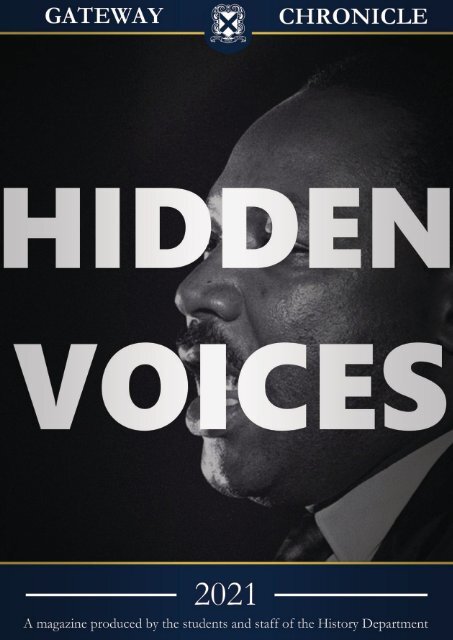

Hidden Voices

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

A Word from the Editors 4<br />

Africa 6<br />

The Development of Medicine in Ancient Kemet 8<br />

The Expulsion of Asians in Uganda 12<br />

A Reappraisal of the Role of the African National Congress 14<br />

Rugby in South Africa 16<br />

Asia 20<br />

The Jallianwala Bagh (Amritsar) Massacre 23<br />

Europe 24<br />

The Tenth Muse: The Loss of Sappho’s Work 26<br />

Medieval Feminism? Christine de Pizan and the Defense of Women 30<br />

The Place of Female Midwives in Early Modern England 33<br />

The Forgotten Male Witches 37<br />

The Last Witch 39<br />

The Role of Irish MPs in the Abolition of the Slave Trade 42<br />

The Impact of Queen Victoria on Women’s Opportunities 45<br />

Should Britain be ashamed of Winston Churchill? 49<br />

Going Underground: The Hidden Voices of Miners 52<br />

The Cultural Integration of British Sikhs 55<br />

The Bristol Bus Boycott 57<br />

Anti-Semitism in England 59<br />

Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Hidden History of Mental Illness 61<br />

2

Hidden Voices<br />

America 64<br />

Harriet Tubman 66<br />

Martin Luther King Jr. 68<br />

Arthur Ashe 72<br />

Silence = Death: A History of HIV and Homophobia 74<br />

Barack Obama 80<br />

Colin Kaepernick 83<br />

Australasia 84<br />

Aboriginal Australians: A Forgotten People 86<br />

The Haka: History hidden in plain sight 89<br />

Credits 92<br />

3

4<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

A Word from the<br />

Editors<br />

In <strong>2021</strong>, when history is popular as ever, we felt<br />

it was more important than ever to give a voice<br />

to those histories that are forgotten or simply not<br />

covered in standard history curriculums. This need<br />

for minority voices to be heard became all the more<br />

apparent after the summer of 2020, which helped<br />

bring new light onto so much of both our history<br />

in Britain and around the world. However, we did<br />

not want the sole focus of this magazine to be about<br />

retelling British history, as this is covered in all<br />

history curriculums. We wanted this to be a journey<br />

through histories not well known throughout time.<br />

To capture this sense of history throughout the<br />

world we divided the magazine into continents.<br />

With articles from Australasia on the Aboriginal<br />

Australians and the origins of the Haka; Africa and<br />

medicine in Kemet in 3000 BC to the ending of<br />

Apartheid; and to Britain itself with a look at mental<br />

health, midwives and medieval anti-semitism.<br />

There are also articles from America, which look at<br />

key figures such as Martin Luther King and Arthur<br />

Ashe; and to Asia and the Amristar massacre. We<br />

were pleased that the articles reflected such a wide<br />

range of the school with articles from the first form<br />

right the way through to teachers.<br />

We would absolutely like to thank everybody that<br />

contributed to the magazine in the writing of their<br />

articles. Moreover, we would like to extend a huge<br />

thank you to Freddie Houlahan and Ciaran Cook<br />

for their work as design editors. We thank them<br />

for their work on presentation and for managing to<br />

turn a collection of articles into a magazine (not a<br />

chance we could have done this from without them).<br />

We would also like to say a thank you to all the<br />

History Department, especially those that contributed<br />

articles and for urging so many students to<br />

take part. In particular we would like to thank Mrs<br />

Gregory for all her support and encouragement in<br />

putting the magazine together.<br />

We hope you really enjoy the magazine and the<br />

chance to learn about some history that is not<br />

typically taught on a history curriculum!<br />

Sam McDonald & Joe Scragg

5<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

The Editorial/Design Team (from left): Sam McDonald, Joe Scragg, Ciaran Cook, Freddie Houlahan

6<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Africa

7<br />

Hidden Voices

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

The Development of Medicine<br />

in Ancient Kemet<br />

The ancient civilisation of Kemet, which first began<br />

in the Nile Valley over 5000 years ago, was incredibly<br />

significant in the development of medicine, the<br />

effects of which can still be found today on modern<br />

society. However, the Ancient Egyptians also made<br />

huge strides forwards in agriculture from developing<br />

magnificent infrastructure to understanding the<br />

best agricultural practices. Their society, although<br />

incredibly influential in medicine, was even more so<br />

in the development in agricultural practices as more<br />

people had access to the benefits and therefore their<br />

quality of life increased more due to the development<br />

of agriculture, than medicine.<br />

Kemet civilisation made huge advances in medicinal<br />

practices which would have increased the life expectancy<br />

and quality of life for its citizens. Although<br />

many were priests, the profession of “physician”<br />

emerged which shows the changing attitudes and<br />

the realisation of the importance of medicine.<br />

Documented Ancient Egyptian medical literature<br />

suggests that physicians specialised in one area,<br />

allowing them to gain in depth knowledge of their<br />

expertise and to become more experienced with<br />

those diseases. Prior to the Ancient Egyptians,<br />

people led a largely nomadic lifestyle, where the<br />

idea of medical infrastructure would not have been<br />

applicable. However, in Kemet there was a system<br />

of government, law enforcement, an organized<br />

economy and a permanent population. This stability<br />

allowed medical research and infrastructure<br />

to develop, which improved the quality of life for<br />

citizens as they gained access to physicians with<br />

medical knowledge. One document from c.3400<br />

B.C.E records over 700 remedies, magical formulas<br />

and incantations to repel disease causing demons.<br />

Although, some of their ideas were flawed in the<br />

cause of disease as they believe it was partly from<br />

the consequence of sin or the patient was under a<br />

“demonic attack”, they understood the importance<br />

of pharmaceuticals in healing, as well as the need<br />

for cleanliness in treating patients. This meant that<br />

many remedies did provide some relief from the<br />

illnesses and therefore there was a large influence<br />

on civilians. There were over 160 medicinal plant<br />

products with one being opium, which was used as<br />

an anaesthetic for tooth extraction. The surgeries<br />

performed were often successful with many surviving<br />

amputations and brain surgery for years; they<br />

even developed wooden amputations, as shown by<br />

the evidence from mummies. They had extensive<br />

surgical equipment, including but not exclusive to<br />

surgical stitches and cauterization, scalpels, forceps<br />

and adhesive plasters. This suggests that the Ancient<br />

Egyptians had methods of managing shock,<br />

blood loss and infection, which were aspects doctors<br />

struggled with until the 20 th century. Therefore,<br />

this shows how advanced their knowledge of medicine<br />

was as they were able to successfully navigate<br />

surgery. This knowledge meant they were able to<br />

treat a wider range of illnesses and diseases, therefore<br />

having a dramatic impact on the quality of life<br />

of Kemet civilians.<br />

8

9<br />

Although the development of medicine was extremely<br />

important for improving conditions for the<br />

Kemet civilisation, the development of agriculture<br />

was even more so. This was because everyone was<br />

able to access the more plentiful food, whereas it<br />

was predominantly just the wealthy who had access<br />

to medicine. Many technological innovations were<br />

developed such as the ox-drawn plough. This used<br />

oxen to pull the plough through the fields which<br />

recycled nutrients within the soil, meaning they<br />

were more successful in growing crops. Therefore,<br />

they had a more stable source of food and nutrition<br />

which is imperative in improving living conditions.<br />

Moreover, this revolutionised agriculture because<br />

it became less labour intensive and more efficient,<br />

allowing them to harvest much larger quantities.<br />

The design was so effective that similar versions are<br />

still being used by farmers in developing countries<br />

in the present day. Another important invention<br />

was the sickle. This was a curved blade used when<br />

cutting and harvesting grain and was significant as<br />

it harvested the staple foods of wheat and barley<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

more efficiently. This helped them gain food security,<br />

thereby increasing their quality of life as they<br />

had reliable access to nutritional foods. This was<br />

more significant than medicine, as if a society is<br />

starving, nutritional food is more important in regaining<br />

strength and health. However, the Ancient<br />

Egyptians irrigation systems which included canals<br />

and dams were the most influential development.<br />

This was because with a reliable water supply, it was<br />

possible to irrigate crops which helped in producing<br />

a constant supply of food, averting disease, malnutrition<br />

and famine. In 3100 BC King Menes, ordered<br />

the first perennial irrigation system to be built,<br />

which diverted water from the Nile into canals and<br />

lakes. This was effective as the River Nile was unpredictable<br />

and the Ancient Egyptians relied on its<br />

seasonal flooding which deposited nutrient rich soil<br />

onto the land. However, the creation of reservoirs<br />

in the canals, meant they could continue to irrigate<br />

crops even when the flood failed. These canals carried<br />

water to numerous farms and villages, so huge<br />

numbers benefitted. This allowed them to create

10<br />

great agricultural wealth and therefore they could<br />

expand their empire. This improved their quality of<br />

life as more technological innovations were developed<br />

as a result from this security. Therefore, although<br />

medicine was important in improving living<br />

conditions for the Ancient Egyptians, agriculture<br />

was even more significant as it helped all corners of<br />

society.<br />

In conclusion, the Ancient Egyptians made some<br />

marvelous breakthroughs in creating a successful<br />

society which lasted for over 3,000 years. These<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

ranged from agriculture to medicine to mathematics<br />

to writing. However, the most influential development<br />

in increasing Kemet civilian’s quality of<br />

life was the improvement of agriculture. This was<br />

because it gave them food security and an export allowing<br />

them to become an extremely powerful empire.<br />

Although medicine was advanced, less people<br />

had access to it and therefore as a civilisation, there<br />

was less of an impact from medicine as it largely<br />

only benefitted the wealthy of Kemet civilians.<br />

Freya Graynoth L6DMY

Hidden Voices<br />

The River Nile, an essential element in the development of agriculture<br />

in Ancient Kemet<br />

11

12<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

The Expulsion of Asians in<br />

Uganda<br />

Idi Amin Dada Oumee was a military officer in<br />

Uganda who served as president from 1971 to 1979.<br />

He was widely known as the Butcher of Uganda,<br />

and completely obliterated the Ugandan economy<br />

during his time in office. He overthrew the previous<br />

president then married into power in 1971, before<br />

initiating his famous expulsion of Asians from the<br />

country only a year later. This came as a result of<br />

Oboto, the former president, planning to get Idi<br />

Amin arrested for using army funds to make himself<br />

seem wealthy and become president.<br />

Idi Amin launched a revolt against the civilians of<br />

the country in January and then moved to secure<br />

strategic positions near Kampala and Entebbe.<br />

In early August 1972 Idi Amin stated he had had<br />

a dream in which God had told him to banish all<br />

Asian minorities from the country, so, a day later<br />

he accused them of disloyalty and not integrating<br />

and expelled them all. During a 90-day period,<br />

about 80,000 Asians (mostly Guajaratis) left the<br />

country, and if they did not leave for whatever<br />

Idi Amin, president of Uganda<br />

between 1971-1979, considered one<br />

of the most brutal despots in world<br />

history<br />

reason, they would be publicly executed. In total,<br />

there was about half a million people put to death.<br />

In this large group of people, only a handful had<br />

their applications for citizenship in other countries<br />

accepted.<br />

Of those 80,000 people, 27,000 went to the U.K,<br />

6,000 went to Canada, 4,500 ended up in India,<br />

2,500 went to Kenya and the remaining 40,000 went<br />

to various other places around the world.<br />

5,655 Asian firms were liquidated and destroyed<br />

along with many ranches, farms, and agricultural<br />

estates. People had to abandon all their major<br />

possessions like cars, houses etc. and were not paid<br />

any compensation; these were all transferred to Idi<br />

Amin. Anyone that possessed a bank account with<br />

any funds lost their money, as it was all transferred<br />

to the Central Bank of Uganda and could not be<br />

accessed.<br />

At the time, my grandfather’s family were in Kampala,<br />

running a shoemaking business. My grandfather<br />

had nearly finished his university<br />

education in India. On his return, he came<br />

back to his family in Kampala to start<br />

a job, but due to the riots and rumours<br />

of Idi Amin taking over the country, his<br />

family applied for a student visa for him<br />

to enter the UK to studying at a college in<br />

London.<br />

My Grandad travelled from Uganda to<br />

the UK, by ship and arrived at the Tilbury<br />

Port. Unfortunately, soon after, my great<br />

grandparents passed away, and my great<br />

uncle had to shut down the family business.<br />

My Grandad started his new life in<br />

the UK.<br />

Idi Amin’s policies affected many Asians,<br />

including both of my grandads, and my<br />

great grandmother.<br />

Ethan Patel 2.3

13<br />

Hidden Voices

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

A Reappraisal of the Role of the<br />

African National Congress and<br />

the Global Black Community in<br />

the Fall of Apartheid in South<br />

Africa<br />

Accounts of the fall of the Apartheid regime in<br />

South Africa have, in the main, been western centric,<br />

calling particular attention to the role of international<br />

economic sanctions, sporting boycotts and<br />

the end of the Cold War between the United States<br />

and the Soviet Union as factors hastening the end<br />

of the racist regime of segregation and oppression.<br />

While these are, of course, vital aspects, such an<br />

analysis tends to overlook or downplay the agency<br />

and power of the African National Congress (ANC)<br />

in shaping the strategy to dismantle Apartheid as<br />

well as developing the role of Black people in Africa<br />

and the wider global community.<br />

Although western-led economic and sporting sanctions<br />

expressed condemnation of the racist Apartheid<br />

system of government, western action was not<br />

as full-throated as we might hope. In Britain in 1964<br />

Harold Wilson’s newly elected Labour Party was<br />

unwilling to impose sanctions and in fact economic<br />

sanctions were not imposed by the United States<br />

and Europe until 1985-1986. In 1964 the future<br />

looked bleak for black people in South Africa. After<br />

the massacre of unarmed Black South Africans by<br />

the police at Sharpeville in 1960, and the government’s<br />

prohibition of the ANC, the leader of the<br />

party, Nelson Mandela, felt he had no alternative<br />

but to abandon the approach of nonviolent protest<br />

in favour of the perpetration of acts of sabotage<br />

against the Apartheid government. After leaving for<br />

Algeria with the objective of training in guerrilla<br />

warfare, he was arrested at a roadblock in Natal and<br />

sentenced to five years of imprisonment. In October<br />

1963, Mandela was tried for treason, sabotage and<br />

violent conspiracy at the Rivonia trial. He made a<br />

speech from the dock, accepting some of the charges<br />

brought against him in a passionate defence of<br />

liberty, democracy and the resistance of tyranny.<br />

His speech which was later titled “I am prepared to<br />

die” brought him respect across the globe. However,<br />

this respect did not translate into direct action from<br />

the west.<br />

Nevertheless, members of South Africa’s Black<br />

community and allies from the South African White<br />

community mobilised a campaign of non-violent<br />

internal resistance. In 1976 in Soweto, a township<br />

near Johannesburg, 20,000 South Africans took part<br />

in a protest led by Black school children to object<br />

to the introduction of Afrikaans, the language of<br />

the Afrikaners who dominated South African politics,<br />

as the language of instruction in Soweto’s<br />

schools which were attended exclusively by Black<br />

South Africans. The police responded violently;<br />

an estimated 400-700 people were killed, many of<br />

them children. This response caused a reluctance to<br />

become involved with such overt political action but<br />

a campaign of peaceful protest nonetheless continued.<br />

Banned ANC flags were flown, clergy married<br />

mixed race couples illegally, funeral marches and<br />

orations were used to protest against the regime as<br />

demonstrations were banned and memorials were<br />

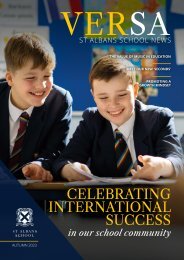

Above: protestors during the 1976 Soweto Uprising<br />

14

15<br />

held such as vigils to commemorate the Sharpeville<br />

massacre. Commercial pressure was also brought to<br />

bear as white-owned shops were boycotted, strikes<br />

were organised by labour groups and rents owed to<br />

white landlords were unpaid. As the tide of change<br />

gained momentum, white-only spaces were utilised<br />

by Black citizens; for example Archbishop Desmond<br />

Tutu led a protest march to a whites-only beach<br />

in 1989 and the National Union of Mineworkers<br />

supported a lunchtime sit-in at an all-white canteen<br />

in the same year. These actions positively impacted<br />

the ruling party’s willingness to negotiate with the<br />

ANC and Nelson Mandela because of the disruption<br />

they caused.<br />

The wider actions of the global community also<br />

affected the dismantling of Apartheid in South Africa<br />

but the scale of influence of Black and alliance<br />

communities and states was wider than that implied<br />

by a western focused narrative. South Africa was<br />

involved in armed conflict against liberation movements<br />

in Angola (1975-1977) and South West Africa<br />

(1966-1989) which drained its economic resources<br />

and morale, the impact of which became more<br />

pronounced when combined with more stringent<br />

economic sanctions in the mid-1980s. The conflicts<br />

are often seen as a case of proxy states fighting<br />

with the support of the United States and the Soviet<br />

Union. Although the Cuban forces who fought<br />

against South Africa were communist, it is clear that<br />

Cuba’s motivation was also based on an anti-colonial<br />

ideology: Fidel Castro pledged forces and weapons<br />

in the spirit of proletariat internationalism<br />

and fittingly named the mission ‘Operation Carlota’<br />

after an African woman who had organised a slave<br />

revolt on Cuba. Despite the roles of international<br />

supporters, the agency of the African protagonists<br />

should not be underestimated. In 1984 Angola and<br />

South Africa signed the Lusaka Accords to declare a<br />

ceasefire. Despite the military support of Cuba and<br />

the Soviet Union throughout the conflict, they were<br />

not consulted by Angola until after the agreement<br />

was signed. This demonstrates their autonomy in<br />

resolving the conflict on their own terms.<br />

A further source of political pressure came from the<br />

African Front-Line States, a coalition of countries<br />

which opposed Apartheid in South Africa. These<br />

included Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia<br />

and Zimbabwe, as well as Angola. They gave the<br />

ANC a base from which to operate during the period<br />

when they were banned in South Africa and put<br />

pressure on other members of the Commonwealth<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

to isolate South Africa.<br />

That these military and political pressures worked<br />

in tandem with economic sanctions from the west<br />

is incontrovertible. However, the role of the global<br />

Black community in bringing about these sanctions<br />

is often overlooked. Black American opinion<br />

was mobilised to exert leverage over US banks<br />

and corporations, who began to divest themselves<br />

of holdings in South Africa during the 1980s. In<br />

response to this economic pressure, the value of the<br />

Rand collapsed.<br />

In this political environment of greater international<br />

co-operation and social and economic pressure<br />

from the majority Black population within South<br />

Africa, when F.W. De Klerk became President of<br />

South Africa in 1989, he confounded expectations<br />

by adopting a great deal of the Harare Declaration<br />

in which the ANC had set out the steps that would<br />

create a climate for beginning negotiations. This<br />

crucial step can be overlooked in the narrative of<br />

the fall of Apartheid but it is clear that the ANC set<br />

the terms of the negotiation: Nelson Mandela was<br />

to be released, bans were to be lifted on outlawed<br />

organisations and the state of emergency was to be<br />

lifted. The majority of the conditions of the Declaration<br />

were met. The leader of the ANC, Nelson<br />

Mandela, created a roadmap of the negotiation process<br />

and the first all-race elections in South Africa<br />

were held in 1994, leading to the ANC winning a<br />

majority and Nelson Mandela becoming its President.<br />

In conclusion, it is apparent that although pressures<br />

from the West in the form of economic and sporting<br />

boycotts were significant factors in the dismantling<br />

of Apartheid in South Africa, the activism of<br />

the Black communities in South Africa itself and<br />

the actions of majority governed African states and<br />

their allies should not be overlooked or downplayed.<br />

A climate in which the negotiations on the road<br />

to democracy could be pursued was only possible<br />

because of the economic pressure caused by wars in<br />

neighbouring states such as Angola and South West<br />

Africa (Namibia) and the internal pressure of economic<br />

boycotts, social protest and disobedience. It is<br />

important that the hidden voices of these contributors<br />

are heard so that their agency in the process is<br />

given due recognition.<br />

Jonathan Webb 4.5

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Rugby in South Africa: How a<br />

World Cup was able to heal a<br />

broken nation<br />

Johannesburg 1995. Joel Stransky’s extra time drop<br />

goal stunned a nation and made South Africa rugby<br />

world champions for the first, but not last, time.<br />

This was their first world cup that marked a significant<br />

return to sport on the global stage, however,<br />

the cultural impact of this victory on racial tensions<br />

is one that should not be underestimated.<br />

Below: the iconic moment when Nelson Mandela presented<br />

Captain François Pienaar with the Webb Ellis Cup<br />

For over thirty years South Africa had been expelled<br />

from almost every major sports federation for<br />

the segregation laws in their country. On the national<br />

level, there was a huge schism between blacks<br />

and whites not only in sport but in every aspect<br />

of life. The apartheid system meant that different<br />

races lived in different parts of town, had separate<br />

swimming pools, schools and entrances to buildings.<br />

Sport was a microcosm for the whole nation as the<br />

national rugby team, the Springboks, became symbolic<br />

of white privilege. Despite their<br />

inclusion of token black players in the<br />

squad, the international team suffered<br />

a complete isolation from international<br />

rugby between 1985 and 1991. The<br />

consequences of this isolation meant the<br />

Springboks could not participate in the<br />

first two Rugby World cups in 1987 and<br />

1991. By 1995 it was a pivotal turning<br />

point in South Africa’s history. They<br />

needed a unifying force to help bring the<br />

country together under one anthem, one<br />

flag, one ‘rainbow nation’.<br />

This unifying force came in the form<br />

of the 1995 Rugby World Cup. When<br />

Nelson Mandela was freed from prison<br />

in 1990 and later became the first president<br />

in 1994, it was his sole aim to fix<br />

a broken country. He rejected the ideas<br />

of some ANC members, who believed a<br />

black president should exploit his powers<br />

to make the whites subservient, but instead<br />

looked for ways to make amends for<br />

South Africa’s past by encouraging equality.<br />

It was this attitude that was a driving<br />

force in the events of the Rugby World<br />

Cup. Mandela saw this as the perfect<br />

opportunity to reinvent South Africa and<br />

restore the nation’s faith in the national<br />

rugby team and, by extension, help to<br />

create a new, racially equal country.<br />

In addition to the racial tension surrounding<br />

the team, the Springboks were<br />

not performing to a high standard in the<br />

16

17<br />

early 1990s. The sports boycott had rendered them<br />

unable to play the amounts of international sport as<br />

the other leading rugby nations and this was beginning<br />

to show when the All Blacks toured in 1992.<br />

This was their first tour to South Africa since 1976<br />

and it resulted in an All Black victory. The Springboks<br />

were booed and berated by their country not<br />

only for their poor quality of sport but due to the<br />

team’s history as an elitist white organization that<br />

was representative of everything that was wrong<br />

with South Africa. In the 1992 tour, the ANC made<br />

several demands: that the old South African flag<br />

not be flown and that the anthem, Die Stem van<br />

Suid-Afrika, not be played. These both held strong<br />

connections to the supposed glory of apartheid and<br />

focused on the triumphs of minority rule. However,<br />

the crowd of 72,000 waved the old flag and<br />

the anthem was played through the stadium’s PA<br />

system, along with racial chants and slurs from the<br />

stands. In addition, the blacks would often cheer on<br />

the opposition in defiance of white supremacy. The<br />

gaping chasm between blacks and whites was still<br />

evident and without a unifying force, the idea of<br />

Nelson Mandela’s “Rainbow Nation” was looking<br />

increasingly unlikely. It is important not to forget<br />

that going into the world cup South Africa were<br />

ranked ninth in the world so a high placed finished<br />

could help to rectify this and change attitudes to the<br />

Springboks.<br />

Another interesting dynamic is that the Springboks<br />

had one ‘token’ black player in the World Cup squad<br />

named Chester Williams. He was the first nonwhite<br />

to play for South Africa since 1984 when his<br />

uncle, Avril Williams, and Errol Tobias were members<br />

of the squad. Due to the separate sport governing<br />

bodies for blacks and whites, coloured players<br />

had not been selected to represent South Africa<br />

before the removal of apartheid in 1991. Being the<br />

third non-white to represent the Springboks carried<br />

a burden. It is undeniable that this was the beginning<br />

of a process that is continuing in South African<br />

rugby, a particular highlight being Siya Kolisi<br />

becoming the first black Captain, but by no means<br />

was this perfect solution. Chester, being the only<br />

player of colour on the team, resulted in him being<br />

paraded as a victory by the rugby board instead of<br />

the start of things to come. However, this also led<br />

to Chester being viewed as a folk hero among rainbow<br />

nation supporters. He became the poster boy<br />

for the world cup with billboards being used to win<br />

around black South Africans to come out in support<br />

to Springboks. There were critics on both sides of<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

the spectrum; those who believed Chester was a glorified<br />

publicity stunt and that there should be more<br />

black players on the team and those who believed<br />

he shouldn’t have been called up in the first place.<br />

However, his popular following by black and white<br />

South Africans alike help to sow the seeds of unity<br />

that would flourish under their unbeaten campaign.<br />

The group stage got off to an excellent start with<br />

South Africa winning all three of their matches including<br />

one against world champions Australia and<br />

a 20-0 victory over Canada. Wins against Western<br />

Samoa and France in pouring rain saw them placed<br />

against New Zealand in the final. The All Blacks<br />

had also won all their games so far and the Springboks<br />

faced them, bitter from their defeat three years<br />

ago.<br />

The final took place in the Ellis Park stadium, in<br />

Johannesburg, in front of a crowd of 63,000. A<br />

myriad of new South African flags greeted the<br />

players as they walked out onto the pitch and the<br />

new national anthem was sung. Mandela had requested<br />

that all the players know the lyrics to Nkosi<br />

Sikelel’ iAfrika to help reinforce unity. 62,000 of<br />

the 63,000 in attendance were of white Afrikaans<br />

decent, the audience that traditionally supported<br />

the Springboks, but the difference this time was<br />

that those who traditionally opposed or berated the<br />

Springboks came out in support of them, watching<br />

in their millions up and down the country. The first<br />

half saw no scores added to the total and the second<br />

half left the two nations at level pegging as the<br />

clock ticked over to extra time. A penalty for each<br />

side left the scores 12-12 but in the last minute of<br />

the first half of extra time, a drop goal from Joel<br />

Stransky wrapped up the match and South Africa<br />

were crowned champions.<br />

After the final whistle had blown, Nelson Mandela<br />

walked out sporting a green and gold jersey and<br />

cap of the Captain François Pienaar. In front of<br />

crowds of adoring South Africans, he shook hands<br />

with Piennar and presented him with the William<br />

Webb Ellis trophy. The shirt that had become synonymous<br />

with racism and apartheid being worn by<br />

South Africa’s first black president was possibly the<br />

greatest public symbol of unity, one that no money<br />

could buy. The symbolic handshake showed the unanimity<br />

of the old and new South Africa and more<br />

importantly it perfectly conveyed Mandela’s desire<br />

for a rainbow nation - a nation where blacks and<br />

white do not just co-exist but care for and respect

18<br />

each other. A nation that does not bury its past but<br />

embraces it and everyone. The whole idea was not<br />

that a new nation was being born but that an old<br />

one was being healed and improved through harmony.<br />

In his acceptance speech, Pienaar said that the<br />

trophy had been won not only for the 60,000 fans<br />

present at Ellis Park for the final but all 43,000,000<br />

South Africans.<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Whilst there are numerous factors that alleviated<br />

racist mindsets in South Africa, the significance of<br />

the 1995 World Cup mustn’t be misrepresented.<br />

Through his interactions with the team, Nelson<br />

Mandela helped to restore the black fans’ faith in<br />

their national team and simultaneously relieved any<br />

fears the whites may have of a black president. The<br />

world cup presented a unique opportunity to showcase<br />

unity on a world stage but also to a nation that<br />

needed unity after so many years of discord. This<br />

was the opportunity for a whole country to get behind<br />

one national force and the world cup provided<br />

the ideal vessel for this. It was the perfect propaganda<br />

campaign that appealed to all races and the fact<br />

the Springboks went onto to win the tournament<br />

only served to ameliorate the concord and goodwill<br />

that always leaves a hazy glow around a country following<br />

a world cup victory. The sweet aftertaste of<br />

the success would be set to continue as the rainbow<br />

nation flourished in the post-apartheid years.<br />

Arthur Roberts L6IMS

19<br />

Hidden Voices

20<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Asia

21<br />

Hidden Voices

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

22

Hidden Voices<br />

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre<br />

In July 2016, my uncle was getting married in India<br />

and my family was invited to attend. We took an<br />

international flight to Delhi and then flew on a domestic<br />

flight to Amritsar, Punjab. The next day, we<br />

went to visit the holy temple of Sikhs: The Golden<br />

Temple. Devotees from different corners of the<br />

globe seek blessings and spiritual solace here. After<br />

taking our blessings we walked to the famous local<br />

park, Jallianwala Bagh.<br />

My mum explained to me the history of the park.<br />

India was once under British rule, and in early April<br />

1919 there was rioting in Punjab. British and Indian<br />

troops under the command of Brigadier-General<br />

Reginald Dyer were sent to restore order and Dyer<br />

banned all public meetings which, he announced,<br />

would be dispersed by force if necessary. On April<br />

13 th , 1919, the Sikh new year (Baisakhi) was being<br />

celebrated. That day, there were over 5000 people<br />

gathered in the park with their friends and family to<br />

celebrate.<br />

The Punjab lieutenant governor called Michael<br />

O’Dwyer is said to have believed that this was part<br />

of a conspiracy to rebel against the British. Troops<br />

under the command of Brigadier-General Reginald<br />

Dyer marched into the walled enclosure of<br />

the park, locked the gates and without any warning<br />

opened fire on the panicked crowd in the park for<br />

about 15 minutes. According to official figures, 379<br />

were killed and 1200 were wounded, although other<br />

estimates suggest higher casualties. Many people<br />

didn’t want to be killed by the gunfire of the British<br />

army so instead they killed themselves by jumping<br />

into a deep well called the “Martyrs’ Well.” Dyer<br />

told his men to cease fire and then left the dead and<br />

the wounded where they lay.<br />

for more about this tragedy.<br />

The news of the massacre spread like wildfire and<br />

provoked strong disapproval. In the House of Commons,<br />

Winston Churchill condemned ‘An extraordinary<br />

event, a monstrous event, an event which<br />

stands in sinister and singular isolation’. Dyer tried<br />

to defend himself but the conclusion of the investigation<br />

was damning; he was severely castigated<br />

and forced to retire from the Indian army. Michael<br />

O’Dwyer was assassinated in London by a Sikh Revolutionary<br />

Udham Singh, who had been wounded<br />

at Jallianwala Bagh. The last known survivor of the<br />

massacre was Shingara Singh – he died in Amritsar<br />

on June 29th, 2009, at the age of 113.<br />

Today, Jallianwala Bagh is a remembrance park for<br />

tourists and locals to pay their respects to the dead.<br />

It is also a quiet garden in the middle of a noisy and<br />

chaotic city, for the locals to have some peace and<br />

solitude. I will never forget this extraordinary place<br />

and cruel piece of history for the rest of my life.<br />

As I write this, Britain has just observed Remembrance<br />

Day on 11th November, commemorating the<br />

loss of lives during the World Wars. It is important<br />

to know that aside from being a colony of the British<br />

Empire, over one million Indian troops served<br />

overseas, of whom 62,000 died and another 67,000<br />

were wounded during World War One. India has<br />

played an important part in shaping the Britain we<br />

know and the freedoms that we enjoy today. This<br />

makes the loss of life at Jallianwala Bagh even more<br />

senseless and saddening.<br />

Arjun Das 1.1<br />

I felt furious and also shocked to hear of<br />

such an event. I couldn’t believe that<br />

so many people had been trapped in a<br />

park and killed mercilessly. Everywhere<br />

I looked there were hundreds of bullet<br />

marks on the walls. We walked over<br />

to the Martyrs’ Well, which had been<br />

boarded up for safety. I imagined women<br />

carrying children and running into the<br />

well to save themselves from the bullets.<br />

The bodies would have piled up on top of<br />

each other, limbs upon limbs. On my return<br />

to the hotel I searched the internet<br />

23<br />

Outside the memorial park in the present day

24<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Europe

25<br />

Hidden Voices

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

The Tenth Muse: The Loss of<br />

Sappho’s Work<br />

Born c. 630 BC, Sappho was to become one of the<br />

most revered poets of her time, her work challenging<br />

popular standards around poetry at the time<br />

and its influence still being felt today. Sappho, or<br />

Psappha in her native Aeolic, is most well-known<br />

today for discussions surrounding her sexuality<br />

and gender in the ancient world –<br />

to an extent this overshadows the<br />

success she deserves to receive.<br />

Yet, for someone who was dubbed<br />

the ‘Tenth Muse’ by Plato, surprisingly<br />

little survives of her poetry<br />

today. Myths and fact often become<br />

confused when understanding the<br />

reasons behind this tragedy but<br />

nevertheless it is fascinating to try<br />

to unravel.<br />

A depiction of Pope Gregory<br />

VII<br />

little evidence to support this idea: it is much more<br />

likely there was a translation error when the scholars<br />

reported it. Joseph Scaliger, a French scholar,<br />

wrote in 1666 of Pope Gregory VII ordering the<br />

destruction of all promiscuous poems and later<br />

commented on Gregory of Nazianzus’ burning of<br />

comedians’ and lyrical poets’ works<br />

in the 4 th century (including Sappho).<br />

It seems that in later years,<br />

there was an understandable confusion<br />

between the Gregories. What’s<br />

more likely is that the reasons<br />

scholars listed for this burning was<br />

not because of both Sappho and the<br />

object of her desire being a woman,<br />

but rather because it was considered<br />

too promiscuous.<br />

One could argue that the most obvious pointer to<br />

Sappho’s sexuality, apart from the subjects of her<br />

poems, are the words ‘sapphic’ and ‘lesbian’ that<br />

find their origins in her name, ‘Sappho’, and her<br />

birthplace, the islands of ‘Lesbos’. While she was<br />

rumoured to have a husband – Kerkyas of Andros –<br />

the chances are he never existed as his name literally<br />

translates to ‘Penis Allcock from the Isle of Man’.<br />

It is likely he was made up as a joke by Sappho’s<br />

contemporaries. Whether this was an attempt to<br />

discredit her is unclear yet later attacks on Sappho<br />

as a result of her sexuality can be easily discerned.<br />

Despite the fact that same-sex relationships were<br />

seen as an act rather than an aspect of one’s self in<br />

ancient Greece, Sappho was still ridiculed for her<br />

sexuality. Anacreontic fragments, a type of poem,<br />

used her as an object to sneer at lesbians as a whole,<br />

New Comedians picked up on this slander and used<br />

the poet as a popular burlesque figure in a number<br />

of plays. In the years after her death, Christian<br />

moralists formally cursed her while even modern<br />

editors changed and edited the lines of her poetry<br />

found to obscure her yearning for women who were<br />

the subject of her poems.<br />

But is her sexuality the reason why so little of her<br />

poetry survives into today? A popular myth is that<br />

Pope Gregory VII in 1073 had Sappho’s poetry<br />

burned since it detailed her lesbian desires. There is<br />

While the myth doesn’t account for the loss of Sappho’s<br />

work, there are several possible reasons that<br />

are more feasible. To begin with, Sappho’s work<br />

continued to be translated and studied considerably<br />

in the Roman Era and throughout its empire,<br />

although towards the end of its period she was less<br />

focused on. Partially due to the transformation of<br />

lyrical to written poetry as well as the movement<br />

into Attic and Homeric Greek, Sappho’s poetry<br />

slipped out of the limelight. The native Aeolic,<br />

which Sappho would have written and spoken, was<br />

notably difficult for Romans to translate and study.<br />

The Aeolic Dialect was the language spoken in<br />

Boeotia, Thessaly and Lesbos and contained many<br />

linguistic nuances unfamiliar and confusing to<br />

Roman scholars, much like how an average reader<br />

would find it difficult to understand Middle English<br />

today. Rather than a ruthless and targeted destruction<br />

of great poetry, it appears as though the sad<br />

reality is that we have so little of Sappho’s poetry<br />

today because of a language barrier. Even celebrated<br />

poet Apuleius commented on the ‘strangeness’ of<br />

her writing.<br />

While the main, and most obvious, reason for the<br />

disappointing lack of Sappho’s poetry remaining today<br />

is indeed translation difficulties, this would have<br />

been further impacted by the change from papyrus<br />

scrolls to parchment. As the demand to study her<br />

work declined, so did the need to transcribe it to the<br />

26

27<br />

Hidden Voices

28<br />

more popular form of book. Sappho’s poetry was<br />

set aside and forgotten as time went on. About 150<br />

years after her death, her poetry was written down<br />

and put into papyrus scrolls for the private libraries<br />

of wealthier people in the 5 th century. Throughout<br />

her lifetime, Sappho had written around 10 000<br />

lines of poetry which were eventually collected into<br />

nine books, now simply referred to as Sappho’s Nine<br />

Books. These were all but lost in the ninth century<br />

as the materials used in book binding and making<br />

improved and it was not thought effort should be<br />

put in to transfer her translation onto the new medium.<br />

Out of the 10 000 lines she wrote, only 650 have<br />

survived into today and only one poem, ‘Ode to<br />

Aphrodite’, is complete. Sappho’s work saw a surge<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Right: a<br />

depiction<br />

of Sappho<br />

from ‘World<br />

Noted Women’<br />

(Mary<br />

Cowden<br />

Clarke,<br />

1858) by<br />

artist Francis<br />

Holl (1815-<br />

1884)<br />

A surviving fragment of Sappho’s work<br />

in popularity following the beginning<br />

of the eighteenth century which resulted<br />

in new copies and translations<br />

of her poetry being published; ancient<br />

authors had their books scrutinised<br />

and thoroughly investigated for<br />

even the smallest quotation. Indeed,<br />

many fragments are simply single<br />

words: Fragment 169A means ‘wedding<br />

gifts’.<br />

Following the end of the nineteenth

29<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

fragments, there can be no doubt that hope still exists for<br />

Sapphic scholars and the desire to give the Tenth Muse the<br />

recognition she deserves.<br />

Milly Caris Harris L6SAH<br />

Above: another fragment of poetry<br />

century, farmers in Egypt started to find scraps of<br />

papyrus and, as news of this arrived in the West,<br />

teams of excavators set about seeing what they<br />

could find. Previously unknown fragments were<br />

found in 1879 at Fayum and between 1896 and 1903<br />

in an Egyptian rubbish dump. The Tithonus Poem<br />

was unearthed in 2004, the fourth poem to have survived<br />

today without many missing fragments. Most<br />

recently, in 2014, Dirk Obbink of Oxford University<br />

announced he had discovered two unseen fragments:<br />

The Brothers Poem and the Kypris Poem.<br />

While some doubt the authenticity of these newest

30<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Medieval Feminism?<br />

Christine de Pizan and the Defence of Women<br />

Although ‘feminist’ claims for women’s emancipation<br />

did not exist in the Middle Ages and education<br />

was restricted, examples of written testimony in<br />

defence of women from misogyny were, perhaps<br />

surprisingly, prevalent. Christine de Pizan provides<br />

many such examples through her writings, and also<br />

her status as France’s first professional woman of<br />

letters; described by some as the Western tradition’s<br />

‘first feminist’. Since the growth of feminist<br />

study in the 1970s, Christine’s extraordinary career<br />

has become known to students of medieval history.<br />

Especially of interest is the stand she takes against<br />

misogyny in a significant proportion of her works,<br />

differentiating her voice from the mainstream discourse<br />

surrounding women’s status in the Middle<br />

Ages. This is clear in her most famous work, The<br />

City of Ladies, however, it is the position against misogyny<br />

that Christine takes in the Querelle de la Rose,<br />

an academic debate surrounding the popular courtly<br />

romance, The Romance of the Rose, that first staged<br />

her career as a defender of women.<br />

Born in Venice around 1364, Christine de Pizan<br />

moved to Paris in 1368 with her family to join her<br />

father, Thomas Pizan, an astrologer at the court of<br />

Charles V. In 1379, she was married to royal secretary<br />

and notary, Etienne de Castel, expanding her<br />

contacts at court. While Christine describes her<br />

education as nothing more than “stealing scraps and<br />

flakes...that have fallen from the great wealth that<br />

my father had”, it is clear from her writings that she<br />

was highly educated, having great knowledge of the<br />

influential works that were of her time, undoubtedly<br />

having access to the royal libraries through her<br />

father’s positions at Court. Following the deaths of<br />

her father (1388) and husband (1389), Christine was<br />

left almost destitute, a widow with three children,<br />

with a niece and her mother to support. Whereas<br />

most widows would have entered a convent or<br />

remarried, Christine was determined to support<br />

her family through the work of her pen. During<br />

this time, it was unheard of for men to achieve this<br />

without subsiding their income from other sources,<br />

such as Court or Church appointments. As a woman,<br />

Christine could not hope to attain such a position,<br />

making her decision to live and support her<br />

family professionally as a writer even more unusual<br />

and daring.<br />

After Christine had established herself through<br />

courtly love poetry, her career began to take a more<br />

anti-misogynist edge, especially influenced by her<br />

reading of the Romance of the Rose. The epic poem<br />

was the best seller in its day; over 200 manuscripts<br />

of it survive, compared to only 84 of Chaucer’s

31<br />

Canterbury Tales. The work was a product of two<br />

authors from separate generations, Guillaume de<br />

Lorris and Jean de Meun, and depicts a dream-vision<br />

experienced by the narrator, portraying an<br />

allegory of courtly love. Jean de Meun’s portion of<br />

the poem added satire and controversy; the allegorical<br />

characters first depicted by Guillaume becoming<br />

more sexually explicit in their language (and in extracts<br />

misogynistic). Furthermore, whilst the Lover<br />

was left appropriately unsatisfied in the first half,<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

Jean’s ending concludes with the conquest of the<br />

rose, an act that is a thinly veiled metaphor for rape,<br />

“I attacked it vigorously and hurled myself at it<br />

time and time again... I forced my way into it, for it<br />

was the only entrance, in order to duly pick the rose<br />

bud”. Despite the obscenity and misogyny found in<br />

the text, its incorporation, to an almost encyclopaedic<br />

range, of classical Latin texts presented in the<br />

vernacular, and its eloquent narrative style acquired<br />

Jean de Meun a near-cult like following.<br />

Corresponding to when the Rose was written, and<br />

when the debate concerning it began, was a revisiting<br />

and reformulation of the ideals of chivalry<br />

and praise of women. This was notably expressed<br />

through new organisations devoted to the defence<br />

of women, such as the Order of the Golden Shield.<br />

During the same period, a parallel movement<br />

formed of highly educated clerks whose literate<br />

values, ‘clergie’, often opposed those of chivalry;<br />

tending to satirise and promote misogynistic<br />

thinking. This attitude against women was derived<br />

from their religious educational background, which<br />

preached Eve’s role in the Fall and similar anti-female<br />

notions.<br />

Within this climate, Christine wrote her earliest<br />

criticisms of the Rose: The Letter of the God of Love<br />

(1399), the Querelle itself (1401-4), and the Tale of<br />

the Rose (1402). In this latter work especially, Christine<br />

draws on the conflicting ideals of the chivalric<br />

and clerkly cultures of France by criticising Jean de<br />

Meun’s Rose. In an allegorical dream vision (similar<br />

to the Rose’s own form) Christine is commanded by<br />

Loyalty to form the Order of the Rose, founded and<br />

run by women, for the defence of their sex from<br />

degrading treatment. Christine thus had a complex<br />

relationship with the Rose and the culture which it<br />

emerged. While she founded her career upon poems<br />

centred around courtly love and chivalry, she clearly<br />

saw the problematic character of those institutions<br />

supposedly created to defend women. Though ‘chivalry’<br />

in modern times has come to signify courtly<br />

and romantic notions of love and civility, this<br />

ignores the predominance of contradictory themes<br />

in the same texts, including the encouragement of<br />

violence and aggression. While the knights of the<br />

chivalric French romances often succeeded in their<br />

missions because of their love for a lady, this trend<br />

had a misogynistic element, and there was steadily<br />

becoming more of an emphasis upon the role<br />

of homosocial bonding in these texts as an ideal<br />

rather than heterosexual love. Although Christine

32<br />

disapproved of Jean de Meun’s work, many of her<br />

own favourite rhetorical strategies (including the<br />

dream-vision as a narrative device and the use of<br />

allegorical personifications) derived from the tradition<br />

of which the Rose was the pioneering text.<br />

By 1401, the Rose had a profound influence, provoking<br />

the intellectual Jean de Montreuil to pen an<br />

enthusiastic praise of both work and author, specifically<br />

Jean de Meun. While Christine’s disapproval<br />

of the text was already established, owing it being<br />

“one of the most notorious compendia of misogynist<br />

lore available in the vernacular”, it was this<br />

letter (no longer surviving) that provoked her to<br />

lay out her arguments against the Rose and become<br />

embroiled in an academic debate which, as a woman,<br />

she had no place in. This<br />

debate continued until<br />

1404, involving many<br />

of the most renowned<br />

intellectuals of the day.<br />

It would have perhaps<br />

been forgotten, if not<br />

for Christine’s extraordinary<br />

step of compiling<br />

the literature involved in<br />

a manuscript which she<br />

presented to the Queen,<br />

thus turning a private<br />

academic disputation<br />

into a public event.<br />

Throughout the Querelle,<br />

Christine’s claims included<br />

that the language<br />

used by Jean de Meun<br />

was vulgar; that several<br />

of the allegorical figures<br />

unjustly defamed<br />

women as a whole; that<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

as well as many of her later writings, have been<br />

labelled ‘feminist’, there is difficulty to applying this<br />

description to a woman of the fifteenth century.<br />

Today’s definition of the term regarding the active<br />

struggle for women’s legal and political equality did<br />

not exist in medieval Europe, and Christine certainly<br />

did not advocate for any reversal of the social<br />

hierarchy. This is highly pertinent to the historiography<br />

that assesses Christine’s defence of women;<br />

while some have praised her for challenging the<br />

dominant misogynist ideology of her age, others<br />

have criticised her for failing to take a more radical<br />

approach. Moreover, ‘feminism’ itself is tricky to<br />

define in a historical context. While it appears to<br />

have a clear meaning, the word itself can be controversial.<br />

Many today who advocate for the equality<br />

that it connotes would<br />

refuse to define themselves<br />

as ‘feminist’. It is therefore<br />

more productive, and less<br />

anachronistic, to employ<br />

the terms proto-feminist<br />

and anti-misogynist when<br />

observing women of the<br />

Middle Ages. Rather than<br />

looking for advocacy of<br />

equality, one should shift<br />

the perspective to the promotion<br />

of women’s intellectual<br />

activity, the defence<br />

of female moral equality<br />

and the affirmation of<br />

women’s contribution to<br />

society. This change in<br />

terminology and outlook<br />

allows Christine, and women<br />

like her, to be viewed in<br />

the context and values of<br />

her own time, allowing her<br />

the conclusion was shameful; overall the work was<br />

an offence to moral decency. Her involvement in<br />

the debate would provide Christine with greater<br />

visibility, some would say notoriety, as a champion<br />

of women’s sensibilities and moral rectitude; her<br />

subsequent works would increasingly take the form<br />

of prose and follow these themes, leading to her<br />

re-writing of women’s history in The City of Ladies.<br />

Hult has thus seen the debate as a crucial staging in<br />

her career, transitioning her from “disenfranchised<br />

woman to female author”.<br />

fundamentally conservative views not to detract, as<br />

some have claimed, from her position as a defender<br />

of women. While Christine’s voice in defence of<br />

women is incredibly different from what we would<br />

expect of a feminist today, it was in its time dissenting<br />

and radical, and one which spoke with as much<br />

urgency as that of any modern feminist.<br />

Ms Hodson<br />

While Christine’s contributions to the Querelle,

33<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

The Place of Female Midwives<br />

in Early Modern England<br />

Many historians have pointed to the early modern<br />

period as a period of widespread professionalisation,<br />

where artisans and craftsman worked with their<br />

respective guilds to try and legitimise their own<br />

occupations, setting themselves apart as the sole<br />

provider of a particular service. This was especially<br />

the case within the world of medicine, with physicians,<br />

barber surgeons and apothecaries seeking to<br />

align themselves as certified medical practitioners.<br />

In doing so, these medical professionals began to<br />

tarnish the reputation and practises of unlicensed<br />

quacks and irregulars. The rise of gender history<br />

since the 1980s has resulted in a large scholarship<br />

surrounding the main victim of this campaign, the<br />

female midwife, who was gradually replaced by the<br />

male accoucheur. However, a revised analysis of this<br />

transition suggests that it should not necessarily be<br />

considered part of a misogynistic narrative. In fact,<br />

the continuing presence of female midwives, particularly<br />

during rural pregnancies, coupled with the<br />

unchanging level of agency granted to pregnant<br />

mothers, suggests that women still maintained a<br />

significant level of power during childbirth.<br />

Firstly, it is perhaps appropriate to outline the place<br />

of midwives within early modern society, so that<br />

their changing role during the period can be assessed.<br />

Typically, midwives cut across a wide social<br />

spectrum and because of this, their experience<br />

as practitioners was equally as diverse. Usually a<br />

mature, married or widowed woman with children<br />

of her own, the early-modern midwife gained her<br />

knowledge from attending the births of children<br />

within her community, and indeed, from her own<br />

experiences of childbirth. Before 1750, pregnancy<br />

and childbirth existed within a predominantly<br />

female-centric sphere; the delivery of the child and<br />

the ritual of lying-in was only attended by women<br />

from the community, known as gossips. Often<br />

lasting for around a month, the lying-in chamber<br />

thus became a sanctuary for female power; it housed<br />

a discourse that simply could not exist outside of<br />

those four walls. For many women this was a unique<br />

opportunity to separate themselves from the traditional<br />

patriarchal society, albeit temporarily, so it<br />

is no surprise that most women within a community<br />

became part of a mother’s pregnancy journey<br />

in some way. For example, a seventeenth-century<br />

ballad commented on the number of women attending<br />

a typical birth and the costs incurred for the<br />

husband; ‘Her Nurses weekly charge likewise, with<br />

many a Gossips feast: he well perceiv’d, when purse<br />

grew light, and emptied was his Chest’. Clearly for<br />

this husband, the extent of the gossip culture in<br />

early modern England was a little more than he had<br />

bargained for.<br />

However, there were times where the sanctuary of<br />

this female-only space was shattered by the presence<br />

of a male surgeon, who primarily attended<br />

to difficult births. This connection meant that the<br />

presence of a male practitioner within the birthing<br />

room therefore became synonymous with a difficult<br />

birth and the possibility of death from mother and<br />

child, so his presence was often met with fear and<br />

Above: a depiction of a woman ready<br />

to give birth from Jane Sharp’s ‘The<br />

Midwives Book’ (1671)<br />

anxiety. Yet, over<br />

the course of the<br />

early modern period,<br />

it became more<br />

common for men to<br />

be part of the process<br />

of childbirth;<br />

some men even entered<br />

the field permanently,<br />

becoming<br />

‘accoucheurs’, or<br />

‘man-midwives’.<br />

Feminist historians<br />

initially attributed<br />

this shift to changing<br />

provision that<br />

sought to eliminate<br />

women from<br />

medical practice,<br />

replacing women’s<br />

power with that of men. Sheena Sommers, for<br />

example, noted how the surgeon Louis Lapeyre<br />

characterised the female midwife as ‘the lowest<br />

class of human being’, and ‘an animal with nothing<br />

of the woman left’. Indeed, even the midwife Jane<br />

Sharp recognised these negative attitudes towards<br />

female midwives. Speaking in her Midwives Book<br />

(1671), the first book on this subject published by<br />

a woman, she stated that ‘some perhaps may think,<br />

that then it is not proper for women to be of this

34<br />

profession because they cannot attain so rarely to<br />

the knowledge of things as men may’. From sources<br />

like this, it is understandable why this shift towards<br />

male midwives has been linked with misogyny<br />

within medicine, as a belief seems to have existed<br />

that women should be pushed out of the profession<br />

and replaced with men. However, recent historians<br />

have cited the rise of the accoucheur as part<br />

of a wider narrative of professionalisation, where<br />

educated, urban, male professionals began to clamp<br />

down on the unlicensed and unregulated practices<br />

of rural quacks. This went alongside the development<br />

of lying-in hospitals for mothers after 1740,<br />

with around a third and a half of all deliveries in<br />

England being attended by medical practitioners<br />

by 1790. However, other historians have suggested<br />

that the development of midwifery training for<br />

male practitioners during the eighteenth century<br />

was simply part of them ‘completing the range of<br />

skills possessed by the old surgeon-apothecary, who<br />

thereby turned into the fully “general” practitioner’.<br />

This argument put forward by Dorothy and Roy<br />

Porter suggests that changing medical provision<br />

enabled practitioners to become the sole caregiver<br />

to a particular family or community. By developing<br />

a strong relationship with an individual from birth,<br />

the eighteenth-century male practitioner became an<br />

early example of today’s general practitioner, and<br />

this eliminated many opportunities for female caregivers<br />

to practice within smaller towns. Therefore,<br />

the shift of female midwives to a supporting role<br />

was not necessarily motivated by intentional misogyny,<br />

but rather, a desire for male physicians to offer<br />

a more holistic approach to caregiving.<br />

This argument regarding professionalisation has<br />

been corroborated by Susan Broomhall. She noted<br />

how, ‘in the sixteenth century, guild organisations<br />

ordered practice and knowledge in a number of<br />

medical fields’. Physicians, surgeons, barber surgeons<br />

and apothecaries would each have had their<br />

own particular guilds that sought to offer training<br />

and support to their members, and although<br />

in continental cities females may have had access<br />

to these guilds, in early modern London this was<br />

strictly prohibited. As a consequence, the practice<br />

of midwifery was often only regulated by the local<br />

church, with midwives receiving ecclesiastical licenses<br />

to attest to their skills within the community.<br />

Therefore, as medicine became more regulated, it<br />

was inevitable that female practitioners would lose<br />

their status and legitimacy within the profession;<br />

however, certain male practitioners also suffered. It<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

is also important to note that it remained possible<br />

for women to become licensed medical practitioners.<br />

In 1691, for example, Margaret Neale applied for a<br />

surgeon’s licence from the ecclesiastical authorities<br />

in England, and a total of sixteen male signatories<br />

testified to her skills:<br />

‘By her own practice (with good success) [she] hath<br />

attained to much expertness in blood-letting (having bled<br />

many gratis) as also dextrousness in pulling out teeth,<br />

and is reasonably well<br />

versed in dressing and<br />

healing all sort of common<br />

and ordinary sores,<br />

pain, cuts, wounding and<br />

ailments belong to the art<br />

of surgery’.<br />

Similarly, a minority<br />

of women had limited<br />

access to medical provision<br />

through the guilds<br />

of their husbands and<br />

often gained some level<br />

of informal training<br />

from male relatives<br />

within their household.<br />

For example, a 1715<br />

advertisement from the<br />

Old Bailey Proceedings<br />

notes how there ‘liveth<br />

a Gentlewoman, the<br />

Daughter of an eminent<br />

Physician, who practised<br />

in London upwards<br />

of forty years … hath<br />

an ointment call’d the<br />

Royal Ointment for the<br />

Gout and Rheumatic<br />

pains’. As such, the<br />

argument that the rise<br />

of professionalism led<br />

to the conscious and<br />

targeted remove of<br />

female practitioners is<br />

simply not true. This<br />

argument loses further<br />

credibility when noting<br />

that the professionalisation<br />

of medicine was<br />

very much an urban<br />

phenomenon, with<br />

most medical provision

35<br />

remaining parochial in England until at least the<br />

late-eighteenth century. Even where formalised<br />

medical institutions existed, the caregiving role of<br />

a woman persisted. For example, Broomhall notes<br />

how, ‘women at all levels were involved in treatment<br />

of the sick, and the maintenance of health, within<br />

their family or household’, and this was not something<br />

reserved for a certain section of society. It is<br />

only due to being unrepresented in contemporary<br />

source material that the voices of these women have<br />

Hidden Voices<br />

not been fully considered. Therefore, although the<br />

rise of the man-midwife was certainly a threat to female<br />

practitioners, they certainly did not undermine<br />

the authority of the traditional midwife overnight;<br />

caregiving within the domestic sphere remained the<br />

responsibility of the wife and mother throughout<br />

this period.<br />

Furthermore, recent scholarship has stressed the<br />

fact that any shift away from female midwives was<br />

actually brought about by women themselves,<br />

in response to changing fashions.<br />

If this is the case, then it completely<br />

undermines the argument that women<br />

were the unwilling victims of this shift<br />

towards man-midwives. Adrian Wilson,<br />

for example, believes that ‘this change …<br />

did not arise from any campaign on the<br />

part of male practitioners to displace the<br />

female midwife; … on the contrary, it arose<br />

from new choices on the part of mothersto-be,<br />

and it appears to have taken male<br />

practitioners by surprise’. The reason for<br />

this sudden transition seems to be largely<br />

focused on the rise in civility after the<br />

sixteenth century. With the breakdown<br />

of traditional community relationships,<br />

many women worked harder to distinguish<br />

themselves from people lower down the<br />

social scale. For women, a way of doing<br />

this was through the employment of<br />

the man-midwife in favour of the poorer<br />

female midwife, whose negative reputation<br />

among some of the educated classes<br />

has already been outlined. This shift was<br />

further encouraged with the introduction<br />

of forceps by Peter Chamberlen in the seventeenth<br />

century; although, they did not<br />

become widely used until a century later.<br />

These instruments became fashionable<br />

among the elites, who saw the possession<br />

of medical knowledge and instruments as<br />

a distinguishing factor between themselves<br />

and the poor. However, the role played by<br />

fashion has, however, been questioned by<br />

Sommers who states that, ‘while the fashionable<br />

appeal of the man-midwife may<br />

have played a part in women’s decision to<br />

employ a male practitioner, women and<br />

their families were unlikely to make such<br />

an important a decision solely on this basis’.<br />

Nevertheless, it remains the possibility<br />

that the pregnant mother retained a certain

36<br />

level of agency throughout this period – particularly<br />

regarding who would be responsible for the birth<br />

of her child. As such, although there was a rise in<br />

the presence of men within the birthing chamber,<br />

this was not always against a mother’s will and did<br />

not necessarily undermine a woman’s power.<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

To conclude, it is certainly true that there was a rise<br />

in the number and presence of accoucheurs towards<br />

the end of the early modern period and many<br />

historians have previously used this as evidence of<br />

the decline of female power. However, the extent<br />

of this shift has perhaps been overstated, due to an<br />

overreliance on traditional, official, male-centric,<br />

urban source material. Instead, throughout this<br />

period, women still maintained a significant level<br />

of power during pregnancy and childbirth. The<br />

continuing presence of female midwives, particularly<br />

during rural pregnancies, coupled with the<br />

unchanging level of agency granted to pregnant<br />

mothers, suggests that they remained in control of<br />

the process. By exploring contemporary sources<br />

further, it becomes clear that midwives remained<br />

an integral part of a woman’s pregnancy journey.<br />

In fact, the continued need for the female midwife<br />

during this period can perhaps be best summed up<br />

by the words of Susanna Watkin during her own<br />

pregnancy: “Godsake either fetch Ellin Jackson (a<br />

midwife) or else knock me on the head!”<br />

Mr Middleton

Hidden Voices<br />

The Forgotten Male Witches<br />

Contrary to the popular thought of a witch with a<br />

black cat, broomstick and screeching cackle, male<br />

witches were common, accounting for 20-25% of<br />

all those tried for witchcraft in early modern Europe.<br />