National English Skills 7

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

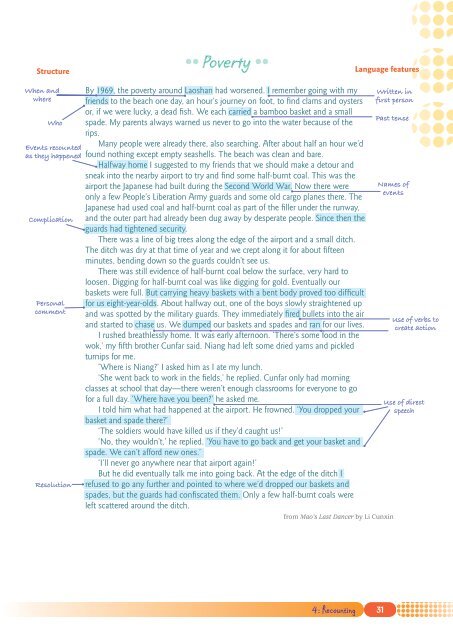

Structure<br />

•• Poverty ••<br />

Language features<br />

When and<br />

where<br />

Who<br />

Events recounted<br />

as they happened<br />

Complication<br />

Personal<br />

comment<br />

Resolution<br />

By 1969, the poverty around Laoshan had worsened. I remember going with my<br />

friends to the beach one day, an hour’s journey on foot, to find clams and oysters<br />

or, if we were lucky, a dead fish. We each carried a bamboo basket and a small<br />

spade. My parents always warned us never to go into the water because of the<br />

rips.<br />

Many people were already there, also searching. After about half an hour we’d<br />

found nothing except empty seashells. The beach was clean and bare.<br />

Halfway home I suggested to my friends that we should make a detour and<br />

sneak into the nearby airport to try and find some half-burnt coal. This was the<br />

airport the Japanese had built during the Second World War. Now there were<br />

only a few People’s Liberation Army guards and some old cargo planes there. The<br />

Japanese had used coal and half-burnt coal as part of the filler under the runway,<br />

and the outer part had already been dug away by desperate people. Since then the<br />

guards had tightened security.<br />

There was a line of big trees along the edge of the airport and a small ditch.<br />

The ditch was dry at that time of year and we crept along it for about fifteen<br />

minutes, bending down so the guards couldn’t see us.<br />

There was still evidence of half-burnt coal below the surface, very hard to<br />

loosen. Digging for half-burnt coal was like digging for gold. Eventually our<br />

baskets were full. But carrying heavy baskets with a bent body proved too difficult<br />

for us eight-year-olds. About halfway out, one of the boys slowly straightened up<br />

and was spotted by the military guards. They immediately fired bullets into the air<br />

and started to chase us. We dumped our baskets and spades and ran for our lives.<br />

I rushed breathlessly home. It was early afternoon. ‘There’s some food in the<br />

wok,’ my fifth brother Cunfar said. Niang had left some dried yams and pickled<br />

turnips for me.<br />

‘Where is Niang?’ I asked him as I ate my lunch.<br />

‘She went back to work in the fields,’ he replied. Cunfar only had morning<br />

classes at school that day—there weren’t enough classrooms for everyone to go<br />

for a full day. ‘Where have you been?’ he asked me.<br />

I told him what had happened at the airport. He frowned. ‘You dropped your<br />

basket and spade there?’<br />

‘The soldiers would have killed us if they’d caught us!’<br />

‘No, they wouldn’t,’ he replied. ‘You have to go back and get your basket and<br />

spade. We can’t afford new ones.’<br />

‘I’ll never go anywhere near that airport again!’<br />

But he did eventually talk me into going back. At the edge of the ditch I<br />

refused to go any further and pointed to where we’d dropped our baskets and<br />

spades, but the guards had confiscated them. Only a few half-burnt coals were<br />

left scattered around the ditch.<br />

from Mao’s Last Dancer by Li Cunxin<br />

Written in<br />

first person<br />

Past tense<br />

Names of<br />

events<br />

Use of verbs to<br />

create action<br />

Use of direct<br />

speech<br />

4: Recounting<br />

31