CEAC-2022-08-August

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

American Street Guide<br />

200 Years of History Unearthed at<br />

Former Slave Quarters<br />

By Maia Bronfman, The Natchez Democrat<br />

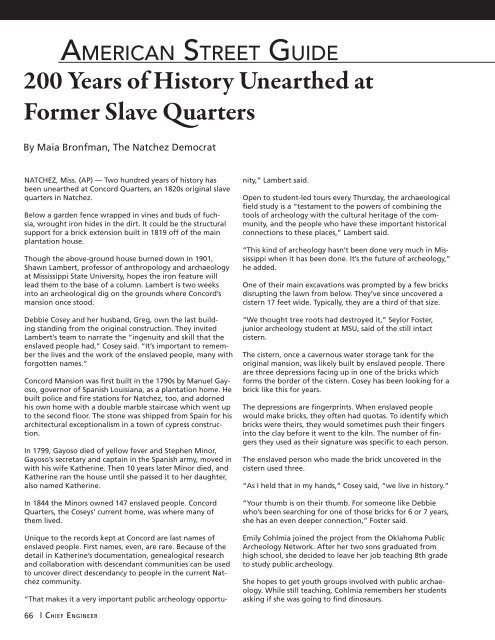

NATCHEZ, Miss. (AP) — Two hundred years of history has<br />

been unearthed at Concord Quarters, an 1820s original slave<br />

quarters in Natchez.<br />

Below a garden fence wrapped in vines and buds of fuchsia,<br />

wrought iron hides in the dirt. It could be the structural<br />

support for a brick extension built in 1819 off of the main<br />

plantation house.<br />

Though the above-ground house burned down in 1901,<br />

Shawn Lambert, professor of anthropology and archaeology<br />

at Mississippi State University, hopes the iron feature will<br />

lead them to the base of a column. Lambert is two weeks<br />

into an archeological dig on the grounds where Concord’s<br />

mansion once stood.<br />

Debbie Cosey and her husband, Greg, own the last building<br />

standing from the original construction. They invited<br />

Lambert’s team to narrate the “ingenuity and skill that the<br />

enslaved people had,” Cosey said. “It’s important to remember<br />

the lives and the work of the enslaved people, many with<br />

forgotten names.”<br />

Concord Mansion was first built in the 1790s by Manuel Gayoso,<br />

governor of Spanish Louisiana, as a plantation home. He<br />

built police and fire stations for Natchez, too, and adorned<br />

his own home with a double marble staircase which went up<br />

to the second floor. The stone was shipped from Spain for his<br />

architectural exceptionalism in a town of cypress construction.<br />

In 1799, Gayoso died of yellow fever and Stephen Minor,<br />

Gayoso’s secretary and captain in the Spanish army, moved in<br />

with his wife Katherine. Then 10 years later Minor died, and<br />

Katherine ran the house until she passed it to her daughter,<br />

also named Katherine.<br />

In 1844 the Minors owned 147 enslaved people. Concord<br />

Quarters, the Coseys’ current home, was where many of<br />

them lived.<br />

Unique to the records kept at Concord are last names of<br />

enslaved people. First names, even, are rare. Because of the<br />

detail in Katherine’s documentation, genealogical research<br />

and collaboration with descendant communities can be used<br />

to uncover direct descendancy to people in the current Natchez<br />

community.<br />

“That makes it a very important public archeology opportunity,”<br />

Lambert said.<br />

Open to student-led tours every Thursday, the archaeological<br />

field study is a “testament to the powers of combining the<br />

tools of archeology with the cultural heritage of the community,<br />

and the people who have these important historical<br />

connections to these places,” Lambert said.<br />

“This kind of archeology hasn’t been done very much in Mississippi<br />

when it has been done. It’s the future of archeology,”<br />

he added.<br />

One of their main excavations was prompted by a few bricks<br />

disrupting the lawn from below. They’ve since uncovered a<br />

cistern 17 feet wide. Typically, they are a third of that size.<br />

“We thought tree roots had destroyed it,” Seylor Foster,<br />

junior archeology student at MSU, said of the still intact<br />

cistern.<br />

The cistern, once a cavernous water storage tank for the<br />

original mansion, was likely built by enslaved people. There<br />

are three depressions facing up in one of the bricks which<br />

forms the border of the cistern. Cosey has been looking for a<br />

brick like this for years.<br />

The depressions are fingerprints. When enslaved people<br />

would make bricks, they often had quotas. To identify which<br />

bricks were theirs, they would sometimes push their fingers<br />

into the clay before it went to the kiln. The number of fingers<br />

they used as their signature was specific to each person.<br />

The enslaved person who made the brick uncovered in the<br />

cistern used three.<br />

“As I held that in my hands,” Cosey said, “we live in history.”<br />

“Your thumb is on their thumb. For someone like Debbie<br />

who’s been searching for one of those bricks for 6 or 7 years,<br />

she has an even deeper connection,” Foster said.<br />

Emily Cohlmia joined the project from the Oklahoma Public<br />

Archeology Network. After her two sons graduated from<br />

high school, she decided to leave her job teaching 8th grade<br />

to study public archeology.<br />

She hopes to get youth groups involved with public archaeology.<br />

While still teaching, Cohlmia remembers her students<br />

asking if she was going to find dinosaurs.<br />

66<br />

| Chief Engineer