Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

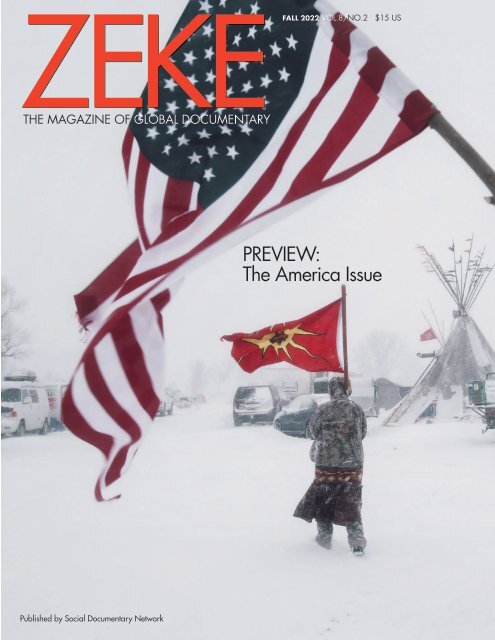

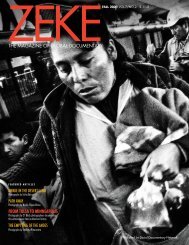

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL <strong>2022</strong> VOL.8/NO.2 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

PREVIEW:<br />

The America Issue<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 1

The<br />

AMERICA<br />

that in our industry and farms and schools<br />

and popular culture and the fine arts we<br />

have created. These achievements must<br />

be embraced while this nation also faces<br />

poverty, addiction, ignorance, and violence<br />

on a scale unknown in most of the<br />

developed world.<br />

As a nation, we are trying to find our<br />

center and regroup, rebuild, redefine<br />

our way finally into a new century that<br />

America. We endure because the was born on 9/11—an event that set<br />

land of the free and home of the brave us back a century, not because of what<br />

was an idea of its time, imperfect in its happened to us but because of how we<br />

exclusions, but a beacon for the modern<br />

world to embrace—a notion that The photographs on the next 46<br />

responded with hubris and arrogance.<br />

all people are endowed with inalienable pages give us a glimpse of who and<br />

rights. Inspiring as this concept may be, what we are today, what we must overcome,<br />

what we can achieve. Our current<br />

there has always been a heavy burden<br />

of detractors who never believed in the president is fond of saying that America<br />

ideal and only cherished their own privilege<br />

in this new land of opportunity. its mind to it. More important though in<br />

can achieve anything it wants if it puts<br />

Divided like this only once before, we reaching our potential is if we can agree<br />

are now walking a delicate path.<br />

on some basic principles and right now<br />

This is the America we seek to this nation is having a hard time doing<br />

describe in this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

just that.<br />

While the term Black Lives Matter It is in this light that we are so proud<br />

was coined just nine years ago, there to present this body of work by 18 photographers<br />

on the theme of America.<br />

was always a deep sentiment of support<br />

for what it means. Yet the fact remained<br />

that Black lives did not matter to the vast<br />

majority of people who just went on in<br />

their (our) ways.<br />

There has always been a darker and<br />

visible underside to this nation as evidenced<br />

in the KKK, the American Nazi<br />

Party, anti-immigrant groups of all kinds,<br />

as well as a softer manifestation of racism<br />

and exclusion in local city councils, state<br />

legislatures, in our places of worship, and<br />

in the Supreme Court of the land.<br />

A nation founded in the idea of human<br />

potential was able to deliver and we see<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong><br />

ISSUE<br />

Robin Fader<br />

Amber Bracken<br />

Cheryl L. Guerrero

Susan Ressler<br />

Kevin McKeon<br />

Anthony Karen<br />

Nick Gervin<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 3

Childersburg, Talladega County, Ala.<br />

Sunshine turns soil in the Commons<br />

Community Workshop garden. 2020.<br />

As a response to national division and<br />

the COVID-19 pandemic, Sunshine<br />

and her husband created the Fearless<br />

Communities Initiative where they<br />

maintain a community garden, host<br />

trade days, and celebrate “solidarity<br />

and strength” while regularly vocalizing<br />

opposition to vaccines and promoting<br />

far-right conspiracy theories.<br />

What Has Been<br />

Will Be Again<br />

Jared Ragland<br />

From Indigenous genocide to<br />

slavery and secession, and<br />

from the fight for civil rights to<br />

the championing of MAGA ideology,<br />

the state of Alabama has<br />

stood at the nexus of American<br />

identity. Begun in fall 2020, the<br />

ongoing project, “What Has<br />

Been Will Be Again,” has led<br />

photographer Jared Ragland<br />

across historic colonial routes<br />

including the Old Federal Road<br />

and Hernando de Soto’s 1540<br />

expedition to bear witness to<br />

and connect with individuals<br />

and communities plagued by<br />

generational poverty, environmental<br />

exploitation, and social<br />

injustices.<br />

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 5

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

In my “America” series,<br />

an ongoing project, I<br />

attempt to portray a<br />

cross-section of a country<br />

filled with overwhelming<br />

pride yet tinged with<br />

sadness and confusion.<br />

To me, the people I photograph<br />

are almost lost<br />

in their own fairy tale. I<br />

try to capture my subjects’<br />

beauty and spirit,<br />

as well as the simplicity<br />

of their surroundings.<br />

After all, I have deep<br />

respect for them, for it is<br />

my fairy tale too, one that<br />

I strived to be a part of<br />

growing up in the Middle<br />

East. It reflects the<br />

movies I watched and<br />

yearned to be a part of …<br />

it is MY America.<br />

US of A Color<br />

Ghada Khunji<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 9

In March 2020, I started working<br />

on a new personal project “COVID-<br />

19 in Black America.” From March<br />

until August 2020, I documented a<br />

group of Black doctors and nurses<br />

providing free COVID-19 tests in the<br />

Black communities of Philadelphia<br />

and surrounding areas. I am now<br />

creating environmental portraits of<br />

Black and brown-skinned people<br />

who have had first-hand experience<br />

with having COVID-19 and recovered,<br />

have lost family members who have<br />

died from the disease, have been<br />

mentally challenged by the year of<br />

being socially isolated, and finally<br />

Black and brown-skinned people who<br />

have figured out how to adjust to the<br />

challenge and made a new pathway.<br />

COVID-19 in Black America<br />

Raymond W Holman Jr<br />

12 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

Both of her parents spent time in the hospital after<br />

developing COVID-19, and her mother died from<br />

it. The entire family was in shock when she died,<br />

since she rarely experienced illness. The day we<br />

created this image, the intention was to also create<br />

images of her father, but because he was home still<br />

not feeling well, on oxygen and mourning the loss<br />

of his wife, I decided not to create those images.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 13

Lost: A Portrait of<br />

Addiction<br />

Virginia Allyn<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

Addiction could be called a plague. It<br />

blights the land. It ravages lives. Flyers for<br />

the missing ask, “Have You Seen Me?” The<br />

toll it takes is devastating. lt is visible night<br />

and day. In Philadelphia, the poorest of our<br />

nation’s largest cities, the plague has worsened.<br />

It is more out of control now. Ten<br />

years ago, one man on Kensington Avenue<br />

remarked, “I would call this the suffering,<br />

the suffering. The only hope I see is that<br />

people get to Heaven when they die.”<br />

Top: She is transgender. “My aunt’s<br />

favorite movie was Pretty Woman. It<br />

portrayed such an amazing lifestyle.<br />

She gets picked up in the street and<br />

ends up with a handsome man and<br />

money and love. But it’s not true in<br />

real life ... I come to the realization<br />

sometimes that I’m never gonna<br />

make it out of here. That’s what<br />

frightens me ... I regret doing heroin,<br />

but I keep coming back to it ... I<br />

want to stay [here]. I can help so<br />

many people that are stuck like how<br />

I’m stuck.”<br />

Bottom: “I’m a registered nurse. I<br />

got radiation poisoning at work and<br />

lost my job ... Everybody’s here for a<br />

different reason.” She has been out<br />

here for two years. “The street got<br />

worse. It’s a horrible place. It’s ugly.<br />

It’s your worst nightmare. People are<br />

just killing people now for nothing.<br />

People forget that this is a neighborhood<br />

and people worked hard to<br />

live in it ... I sleep on the pavement.<br />

Wherever I pass out. I’ve been trying<br />

to get into a shelter, but they closed<br />

two shelters down here. I prostitute.<br />

I hate it. I’m scared all the time ...<br />

I’m either going to go to rehab or I’m<br />

going to die.”<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 23

Arming<br />

Teachers<br />

in America<br />

Kate Way<br />

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

“I think it’s good to educate our kids in the<br />

same way....We’ve talked about it in our<br />

home, you know we have plans…I mean<br />

some people do fire drills. What happens<br />

if the smoke alarm goes off, where do you<br />

go? [My husband] and I have said what<br />

happens if an intruder comes in? [In one<br />

room of our house] we put in a steel door<br />

with a peephole. So we kind of have a safe<br />

room where we can go.”<br />

— Christin Forbes, suburban elementary<br />

school teacher and mother, attending day<br />

one of the FASTER training.<br />

This photo accompanies an essay<br />

that explores the highly controversial<br />

trend of K-12 schools arming<br />

teachers and other school staff<br />

in the United States. Since the<br />

Sandy Hook Elementary School<br />

massacre in 2012—and the<br />

more recent school shootings in<br />

Parkland, FL and Uvalde, TX—well<br />

over a dozen states have begun<br />

arming teachers. Shockingly, no<br />

one official federal or state body<br />

has been keeping count of how<br />

many schools across the nation<br />

have armed staff, and in many<br />

communities, even the parents<br />

and the general public remained<br />

uninformed. Often without public<br />

knowledge, there are teachers,<br />

administrators, custodians,<br />

nurses, and bus drivers carrying<br />

guns in America’s schools. This<br />

photograph was taken at an Ohio<br />

gun-training program designed<br />

for school staff in a community<br />

divided over arming its teachers.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 25

White Nationalism<br />

Anthony Karen<br />

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

Top: Charles (36), a Lieutenant<br />

in the NSM (National Socialist<br />

Movement), addresses the crowd<br />

shortly before a swastika lighting<br />

ceremony at the Hated and Proud<br />

concert, which was held on a<br />

small farm in America’s heartland,<br />

Iowa.<br />

While documenting an ongoing project on<br />

the Ku Klux Klan, I came in contact with<br />

several organizations within the White<br />

nationalist movement. I’ve had the unique<br />

opportunity to photograph many of these<br />

groups without restriction over the past<br />

thirteen years and I will continue to do so<br />

for the long-term. The following images are<br />

a look into their private and social lives.<br />

Middle: A Ku Klux Klan cross<br />

lighting ceremony and swastika<br />

lighting — according to Klan ideology,<br />

the fiery cross signifies the<br />

light of Christ and is also meant to<br />

bring spiritual truth to a world that<br />

is blinded by misinformation and<br />

darkness.<br />

Bottom: A female skinhead,<br />

known as a Skinbyrd.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 27

Sex Trafficking:<br />

An American Story<br />

Matilde Simas<br />

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

When people hear that someone<br />

was trafficked, it’s often<br />

assumed they were kidnapped<br />

and forced into labor against<br />

their will. Trafficking can be<br />

much more insidious. People<br />

are often exploited by someone<br />

they already know.<br />

In this photo documentary,<br />

we listen to the story of Cary<br />

Stuart, an American survivor<br />

of forced commercial sexual<br />

exploitation, who was lured<br />

into the world of trafficking by<br />

a romantic partner or “Romeo<br />

Pimp.” In the series, she<br />

reflects on her experience, the<br />

way it has impacted her mental<br />

state, and the ongoing challenges<br />

of working through drug<br />

addiction. Addiction to drugs<br />

can be both a vulnerability to<br />

trafficking, and a common tactic<br />

used by traffickers to make<br />

victims more compliant.<br />

While the prevalence of sex<br />

trafficking in the U.S. is still<br />

unknown, we do know that<br />

women, children, and men are<br />

being sold for sex against their<br />

will in all 50 states. In 2014,<br />

the Urban Institute studied the<br />

underground commercial sex<br />

economy in eight U.S. cities<br />

and estimated that this illicit<br />

activity generated between<br />

$39.9 million and $290 million in<br />

revenue depending on the city.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 31

Working Ohio<br />

Steve Cagan<br />

34 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

Clockwise starting above.<br />

Electrical maintenance worker<br />

Living in Cleveland, I’ve<br />

witnessed the dramatic<br />

decline of what was a<br />

major industrial center,<br />

where thousands of people<br />

worked in good-paying,<br />

secure jobs, creating,<br />

building, and producing<br />

through physical and mental<br />

strength. That is largely—<br />

but not entirely—gone.<br />

Today, the media talks<br />

about trying to recover jobs<br />

lost during the pandemic.<br />

Jobs lost between the 1970s<br />

and early 21st century aren’t<br />

even discussed any more.<br />

And those people who<br />

still work in Cleveland in<br />

union jobs—in what remains<br />

of our industry—are unseen<br />

and unappreciated by the<br />

media and the art world.<br />

We documentarians<br />

must present people not<br />

only as victims of social<br />

problems, but also as<br />

strong, creative, resistant—<br />

which in fact they are.<br />

Chicken plant workers<br />

Hotel housekeeper<br />

Ironworkers<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 35

Good Earth<br />

Esha Chiocchio<br />

Good Earth celebrates New<br />

Mexican agrarians who are<br />

revitalizing land through<br />

regenerative practices—building<br />

soil, sequestering carbon,<br />

reducing toxins, and improving<br />

the health of people,<br />

plants and animals.<br />

To better understand the<br />

range of regenerative techniques<br />

being employed,<br />

podcast host Mary-Charlotte<br />

Domandi and photographer<br />

Esha Chiocchio used interviews<br />

and photography to<br />

document the techniques of<br />

Native American land managers,<br />

farmers, composters,<br />

ranchers, goat herders,<br />

orchardists, and soil scientists<br />

to improve the foundation<br />

of society: soil. This series<br />

provides a window into regenerative<br />

land stewardship and<br />

demonstrates how we can all<br />

play a role in rehabilitating the<br />

good earth.<br />

46 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

Above: Tommy Casados inspects the<br />

grass as he flood-irrigates one of his<br />

pastures at C4 Farms in Tierra Amarilla,<br />

New Mexico. Tommy grazes fewer<br />

cattle than his land could technically<br />

accommodate with the goal of growing<br />

an abundance of healthy, deeply<br />

rooted pasture. Such practices encourage<br />

the soil to absorb more carbon,<br />

thereby reducing greenhouse gases and<br />

increasing resilience to both flooding and<br />

drought.<br />

Above: Gordon Tooley hand cuts<br />

grasses to harvest the seeds and<br />

spread them to new areas of his<br />

orchard, Tooley’s Trees. Keeping<br />

the ground covered with diverse<br />

vegetation is an important aspect<br />

of creating a regenerative orchard<br />

that absorbs carbon and builds rich,<br />

biologically active soil.<br />

Left: Josh Bowman with his sons,<br />

Ephraim and Emerson, at their pecan<br />

farm in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Most<br />

pecan farmers in the region clear the<br />

floor beneath their trees of any vegetation.<br />

Consulting with soil scientist Dr.<br />

David C. Johnson, Josh has grown<br />

cover crops, used compost teas, and<br />

incorporated a flock of sheep into his soil<br />

management strategies to build organic<br />

matter and encourage a healthy microbiome.<br />

Josh and his sons have an evening<br />

practice of digging for earthworms,<br />

which have steadily increased as the soil<br />

has improved.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 47

Who<br />

“<br />

WEARE<br />

Photography<br />

and the<br />

American<br />

Experience<br />

by Stephen Mayes<br />

The American Dream” has<br />

always been an aspirational<br />

phrase, founded on the<br />

promise of economic opportunity<br />

(think white picket-fenced<br />

homes) and an idea that all people<br />

who live here are free and equal. For<br />

over a hundred years, photography<br />

has tried to document this ideal: showing<br />

who we are, demonstrating our<br />

achievements, marking our failures and<br />

inspiring our hopes, making<br />

visible for all to see<br />

across divisions of geography,<br />

class and political<br />

persuasion. But, today in<br />

the 21st century, the meaning<br />

of the American Dream<br />

has been obfuscated,<br />

reduced to hollow political<br />

messaging from both sides<br />

of the aisle, making it even harder to<br />

have a clear picture of what America<br />

really is and what it looks like.<br />

In the 20th century, America was a<br />

story told with the simplicity of single<br />

images in an age when the nation’s<br />

eyes could be focused collectively and<br />

simultaneously on one front page,<br />

a national story that was led by the<br />

unified drum beat of mass media that<br />

drove the news agenda.<br />

One story followed another in a<br />

more or less choreographed progression<br />

as the media gathered itself<br />

around each new issue and gave it<br />

shape in the public eye. This was the<br />

age of the iconic image, when a single<br />

photograph would find itself exposed<br />

to everyone at the same moment, and<br />

in feeling the moment, the viewers<br />

would imbue meaning in the image<br />

beyond the simple facts represented.<br />

This was America.<br />

Now, as we look back, some of<br />

these images have withstood time and<br />

still stand as symbols of the national<br />

will for progress, the celebration of<br />

achievement as well as moments of<br />

unified national despair. A migrant<br />

mother, the raising of the flag at Iwo<br />

Jima, a Saigon street execution, a<br />

video grab of a Black motorist being<br />

assaulted by a group of LA police<br />

officers and a flag raising at Ground<br />

Zero. Each of these widely known<br />

images evokes not just an American<br />

story but also conjures a host of references<br />

and associated emotions representing<br />

the spirit of the times. While<br />

speaking truths there is also a danger<br />

that such icons compress the narrative<br />

too much, simplifying complex stories<br />

and reducing the rich weave of history<br />

to clichés, assumptions and stereotypes.<br />

For a nation that’s still less than<br />

250 years old, one could think of 20th<br />

century America as still an adolescent<br />

culture, disguising its insecurities in<br />

consistent dress codes: the U.S. flag<br />

was (and still is) everywhere, marking<br />

everything and everybody as members<br />

of a new and strong nation. In this<br />

context the iconic images were appropriately<br />

powerful and told a simplified<br />

Right: Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange.<br />

Florence Thompson, 32, a pea picker and<br />

mother of seven children. Nipomo, CA.<br />

1936. Farm Security Administration—<br />

Office of War Information Photograph<br />

Collection, Library of Congress.<br />

Susan Ressler<br />

48 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> SPRING <strong>2022</strong>

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 49

Elyse Blennerhassett<br />

Interview<br />

DONNA FERRATO<br />

Donna Ferrato, an internationally acclaimed and<br />

award-winning photojournalist, is known for her<br />

groundbreaking documentation of the hidden<br />

world of domestic violence, an issue she spent<br />

years photographing. These images were published<br />

in her seminal book Living With the Enemy<br />

(Aperture, 1991) which, alongside worldwide<br />

exhibitions and lectures, sparked an international<br />

discussion on sexual violence and women’s rights.<br />

A longtime activist, in 2014 Ferrato launched the<br />

I Am Unbeatable campaign to expose, document,<br />

and prevent domestic violence against women<br />

and children through real stories of real people. In<br />

her new award-winning book, Holy, published in<br />

2020 by powerHouse Books, Ferrato repurposes<br />

her images, that combined with handwritten text,<br />

proclaim the sacredness of women’s rights and<br />

their power to be masters of their own destiny. For<br />

more information, see www.donnaferrato.com<br />

By Michelle Bogre<br />

Michelle Bogre interviewed Donna Ferrato<br />

at her Tribeca loft on July 29, <strong>2022</strong>.<br />

Michelle Bogre: When did you realize<br />

you were an activist photographer, not<br />

just a photojournalist?<br />

Donna Ferrato: In 1993. I was in<br />

Bruce, Mississippi covering the funeral of<br />

seven children who were burned alive in<br />

a house fire because there were bars on<br />

the windows that locked from outside the<br />

house. The family—children and grandmother—<br />

were trapped inside, as if in a<br />

prison. No magazines were interested so<br />

I went on my own. As soon as I arrived,<br />

I saw people gathered around someone<br />

who had collapsed. Women in white<br />

dresses surrounded her. I figured it was<br />

the mother who was incarcerated but<br />

received a day pass to attend the funerals<br />

of her mother and her seven children. I got<br />

down on my knees and crawled between<br />

women’s legs to get the picture of a mother<br />

with a broken heart. Nobody tried to stop<br />

me. Sometimes I feel invisible. Perhaps<br />

people didn’t stop me because they could<br />

see at that moment I was upset, having<br />

trouble focusing through my tears. People<br />

saw I was not dispassionate.<br />

My activism evolved trying to make<br />

sense of that story. I saw what I had to<br />

do—investigate as well as photograph<br />

and find ways to publish stories about<br />

the crimes against women, domestic<br />

violence, and criminalized survivors of<br />

domestic violence.<br />

MB: Crawling between someone’s legs<br />

to get a picture seems a bit aggressive.<br />

DF: I don’t think people realize how<br />

invasive I am. To get a photograph, I will<br />

go to hell and back. It was hard to get<br />

access to battered women’s shelters when<br />

they were completely off-limits to the<br />

press. I had to get inside to convince the<br />

shelter directors, the residents, the police,<br />

the prison superintendents, hospital<br />

administrators, even the violent abusers<br />

being arrested. I lived it with people,<br />

whatever they were going through, even<br />

in prison or in their homes.<br />

MB: Was the story published?<br />

DF: Yes. I took a set of photographs<br />

to People magazine. The editors were<br />

interested and sent me back with a<br />

great writer, Bill Shaw. We met with the<br />

landlord, Mr. Chandler. While Bill was<br />

interviewing him, I had a chance to get<br />

the proof that Chandler was responsible<br />

for their deaths. He could have saved the<br />

family because he had the keys to the<br />

bars on the window. I saw the photo: he<br />

was lying on a couch under a window<br />

where the ring full of keys was hanging.<br />

Click. One Sunday at church, I spoke<br />

to the congregation. I told them I didn’t<br />

believe that God called the children to<br />

Heaven; it was human negligence. I<br />

suggested they form a committee, attend<br />

monthly town meetings, and see what the<br />

fire codes were. I wanted them to understand<br />

that they had rights and the more<br />

they knew, the better chance they had<br />

to change the law—maybe outlaw those<br />

dangerous metal bars that killed people.<br />

The committee was led by one armed<br />

woman, Minnie, the deceased children’s<br />

aunt. They eventually changed the law in<br />

Jackson, Mississippi and when I saw how<br />

successful they were, I decided I would<br />

never be a quiet photographer. From that<br />

point, I’ve always spoken my truth to the<br />

people I photographed.<br />

MB: How can you be so invasive, to use<br />

your word, and still get intimate photographs?<br />

DF: People may see some madness in<br />

how I do what I do so they don’t stop me.<br />

I don’t care how strange I look. I’ll crawl<br />

on my belly. It’s about being there. My<br />

size works in my favor. I am small, agile,<br />

and fast. Most of the time, I prefer being<br />

lower than the people I’m photographing.<br />

I don’t ever want people to feel like I am<br />

towering over them.<br />

MB: That’s visible in your pictures. You<br />

bring the viewer into what feels like an<br />

intimate moment.<br />

DF: When I teach, I try to help photographers<br />

see that they don’t have to stand<br />

in a corner to be unobtrusive. Often<br />

the view is right in front of our eyes.<br />

Wherever the photographer stands it’s<br />

important to be in the moment, to absorb<br />

everything, sorrow, pain, anger, love. Let<br />

emotion enter the images through us.<br />

MB: You use a 35 mm or wider lens?<br />

Leica rangefinder?<br />

DF: I use a Leica M10. Leica has been<br />

my weapon of choice since 1976 when<br />

I had a Leica M4. Most often I work<br />

with a 35 mm lens. It’s one camera, one<br />

lens, one woman. I am never without my<br />

camera.<br />

MB: Never?<br />

DF: Why in the world would I go<br />

anywhere without my beloved camera?<br />

The camera is me. Photography is a<br />

calling. Often, we have no choice. As a<br />

young woman, I realized that I had an<br />

instinct to frame and extract what matters<br />

from that moment, the good, the bad, the<br />

ugly. I would lose my mind if I couldn’t<br />

photograph.<br />

MB: You do have an extraordinary<br />

instinct for the perfect moment. One of<br />

the images in your book, Holy, titled<br />

Diamond, Minneapolis, is almost perfect.<br />

54 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>

The eight-year-old boy called 9-1-1 to report his father. When the police arrived to arrest his father, Diamond<br />

said, “I hate you for hitting my mother. Don’t come back to this house.” This photograph was awarded one of the<br />

most influential 50 photographs. © 1987 Donna Ferrato/ LIFE Magazine<br />

You captured the moment when the boy is<br />

shaking his finger at his father, and there<br />

are three cops, and the battered women’s<br />

face is framed in a “V” between two of the<br />

cops, the television is on, but the perfection<br />

is the White cop’s hand in the Black<br />

man’s pocket.<br />

DF: White and Black…mmm, yes, well,<br />

when I entered the house tagging behind<br />

the cops that morning, it was early, and<br />

the curtains were drawn. Everything<br />

happened fast, hard core drama. I had a<br />

flash, and was fumbling trying to get it on<br />

the camera, to bounce it off the ceiling.<br />

As the cops brought the father into the<br />

living room, I was ready but every time<br />

the flash popped I couldn’t see what was<br />

happening. I heard what the boy was<br />

saying because I was next to him. The<br />

police were going through the father’s<br />

pockets, to make sure there were no<br />

weapons. The boy was angry with his<br />

dad, he was angry with everyone. Later,<br />

when the film was developed I saw it was<br />

the picture as I imagined it would be. But<br />

honestly, it’s all instinct. It’s Jedi Warrior<br />

photography. But I didn’t have a signed<br />

release. I went back a month later to meet<br />

the parents and they signed a release,<br />

which was necessary to be published in<br />

LIFE Magazine.<br />

DF: There is no detachment. Injustice is<br />

always gut-wrenching. A photographer<br />

sees right through everything. We have<br />

to get the best photograph whatever happens,<br />

but it’s complicated. I can’t say that<br />

I don’t absorb their feelings, but clearly,<br />

I don’t suffer the consequences like the<br />

people in the photographs. Some of the<br />

people were thankful that I was there.<br />

Not everybody. Many people would<br />

like to forget these things happened.<br />

Photographs make it hard to forget. I<br />

too become trapped in the frame of that<br />

moment. We all suffer from collective<br />

trauma. Every time I relive these incidents,<br />

I relive them and become anxious,<br />

depressed, especially now as things are<br />

worse than ever. Domestic violence is<br />

more difficult to predict, to contain, to<br />

prevent. My purpose now as a human<br />

being is to keep these photographs in the<br />

forefront of human consciousness, as an<br />

activist and a witness<br />

MB: What is your new project, Wall of<br />

Silence?<br />

DF: The Wall of Silence was my response<br />

to an open call from the NYC Mayor’s<br />

Office to end gender-based violence, a<br />

chance to create art that would inspire<br />

activism about the criminalization of survivors<br />

of gender-based violence. My idea<br />

was to build a prison wall with a stainless<br />

steel mirror, to create a portal by which<br />

people would see themselves and hopefully<br />

relate to the horror of being unjustly<br />

incarcerated. I chose the Collect Pond<br />

Park in lower Manhattan as the location<br />

because of its proximity to the criminal<br />

and family courthouses, where too often<br />

survivors —especially Black,Brown, and<br />

LGBTQIA+ people—lose their rights<br />

because they defended themselves and<br />

their children. On the day we unveiled it<br />

in the park, a survivor, Tracy McCarter,<br />

currently facing incarceration, appeared<br />

almost as if she was transported through<br />

the Wall of Silence. The project brought<br />

Tracy into my life and now I am working<br />

on telling her story as it unfolds in one<br />

of the courthouses facing the sculpture.<br />

Through this project, I hope to not only<br />

educate society, but to be a witness and<br />

put pressure on the court system to feel<br />

compassion for survivors of gender-based<br />

violence. I am using the installation to<br />

disrupt the silence by engaging the public<br />

and the media to support Tracy’s case. Her<br />

story is another example of how society<br />

and the courts are stripping women of<br />

their rights: their reproductive rights, their<br />

rights to bodily autonomy, to the basic<br />

human right of self-defense, and their right<br />

to the pursuit of happiness to live as free<br />

and equal human beings.<br />

MB: In the profession we talk about<br />

secondary trauma. You’ve seen a conflict,<br />

violence and injustice. How do you<br />

absorb the violence or does the camera<br />

provide detachment?<br />

Mississippi Fire, 1993. Ether Ree Hall Gaston, mother of six of the dead children, collapses in the gymnasium<br />

where the funeral is being held. Doing time for drug trafficking, she was let out of prison for the day.<br />

©1993 Donna Ferrato<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2022</strong>/ 55