ZEKE Magazine: Fall 2021, Preview edition

Subscribe and read full version.

Subscribe and read full version.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

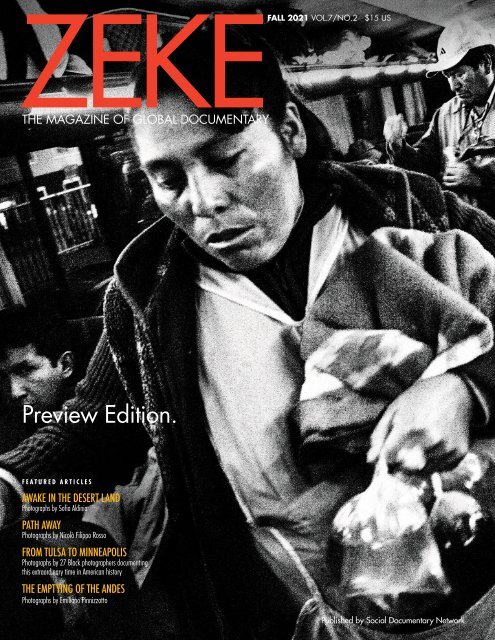

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2 $15 US<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

<strong>Preview</strong> Edition.<br />

FEATURED ARTICLES<br />

AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting<br />

this extraordinary time in American history<br />

THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Published by Social Documentary <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL Network <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

FALL <strong>2021</strong> VOL.7/NO.2<br />

$15 US<br />

2 | AWAKE IN THE DESERT LAND<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Sofia Aldinio from Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Nicolò Filippo Rosso from Path Away<br />

Joshua Rashaad McFadden from From Tulsa to<br />

Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to<br />

Justice<br />

Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying of the<br />

Andes<br />

14 | PATH AWAY<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

CO-WINNER OF <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

40 | FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS:<br />

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

60 | THE EMPTYING OF THE ANDES<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

26 |<br />

30 |<br />

52 |<br />

54 |<br />

70 |<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

The Last Resort to Stay Alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> Award Honorable Mention Winners<br />

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

78 | Contributors<br />

Deborah Espinosa from Photography & Social<br />

Change<br />

On the Cover<br />

Photo by Emiliano Pinnizzotto from The Emptying<br />

of the Andes. Inside a bus heading in the direction<br />

of Lima. Many of the people inside the bus are<br />

leaving their homes forever, looking for a job and<br />

a better life in the cities. See inside back cover for<br />

a profile of Emiliano Pinnizzotto.

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

THE<br />

MAGAZINE OF<br />

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Dear <strong>ZEKE</strong> Readers:<br />

As I write this letter, Hurricane Ida has just completed its deadly flooding and destruction in Louisiana and the<br />

Northeast exactly 16 years after Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. Floods have killed 20 people in Tennessee.<br />

Wildfires rage in the West and in Europe. And the Delta variant of COVID-19 extends its grip.<br />

It has also been just a few weeks since the fall of Kabul as the Taliban swept into victory following the<br />

American pullout after our 20-year failed effort at nation building. Now a chaotic and deadly evacuation<br />

has ended for U.S. troops, American citizens, our Afghan allies, and nationals of other countries struggling<br />

to flee the imposition of a harsh and despotic rule that we all know too well from the years prior to 9/11<br />

when the Taliban last controlled Afghanistan.<br />

While none of these events are presented in this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, prior issues have featured numerous<br />

articles on climate change and the U.S. "War on Terror." We continue to publish <strong>ZEKE</strong> because we stand<br />

resolutely behind the importance of the documentary image, and the photographers who make them, in<br />

bringing awareness, nuance, and humanity to global issues.<br />

In this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, we are thrilled to present the winners of the <strong>2021</strong> <strong>ZEKE</strong> Award for Documentary<br />

Photography. Sofia Aldinio’s award-winning project, Awake in the Desert Land, explores migration and historical<br />

memory as residents from Baja California, Mexico are uprooted from their land as a result of climate<br />

change. Nicolò Filippo Rosso’s project, Path Away, follows migrants from the Northern Triangle countries<br />

(Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador), as they flee violence and climate change to seek better opportunities<br />

in the U.S. only to find the border sealed as they approach their destination.<br />

We also present the extraordinary images by Italian photographer Emiliano Pinnozzotto and his project,<br />

The Emptying of the Andes, documenting an important, under-reported, and all too common story, where<br />

young people are fleeing their ancestral mountainous homes only to find a new form of poverty and alienation<br />

in urban centers—in this case in Peru—as climate change makes it increasingly difficult to sustain life<br />

at 13,000 feet.<br />

It is no coincidence that migration is a central theme in these three exhibits as the existential threat of<br />

climate change forces millions of people each year to seek less vulnerable environments.<br />

We are also thrilled to present 27 submissions from a call for entries from Black photographers on the<br />

theme “From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the Long Road to Justice” including first-place winner<br />

Donald Black Jr. for his story A Day No One Will Remember.<br />

In addition to these portfolios, Emily Schiffer has written a very provocative and inspiring feature article<br />

on Photography and Social Change exploring photographic artists who are making a difference by challenging<br />

the norms of both imagemaking and traditional structures of power.<br />

Lastly, on a personal note, I am very saddened to report that the namesake<br />

for <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine, our thirteen-year-old beloved feline companion Ezekiel<br />

(aka Zeke), passed away in July following injuries suffered from a valiant fight<br />

with a wild animal. Barbara and I take solace that his exuberance for life, his<br />

unbounding energy, and his persistent demand for dignity often denied our<br />

non-human friends, live on in this magazine.<br />

Matthew Lomanno<br />

Glenn Ruga<br />

Executive Editor<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 1

This ongoing photography project<br />

by Sofia Aldinio documents<br />

how climate change is uprooting<br />

small, inland and coastal<br />

communities in Baja California,<br />

Mexico, that depend directly on<br />

natural resources to survive and thereby<br />

threatening cultural heritage.<br />

The peninsula is facing stronger hurricanes,<br />

changes in precipitation patterns<br />

and streamflow, loss of vegetation<br />

and soils and negative impact on fisheries<br />

and biodiversity. It is estimated that<br />

in Mexico and Central America, 3.9<br />

million people will be forced to leave<br />

their homes due to climate change.<br />

Photographed in four different communities<br />

across the peninsula, the work<br />

presented here documents the tension of<br />

the communities whose cultural heritage<br />

is at risk, adds a new perspective on<br />

the existing reports on climate change<br />

and migration and starts a conversation<br />

about how the loss of collective memory<br />

has a direct impact on the mental health<br />

of the next generation.<br />

The newest cemetery in San Jose de<br />

Gracia, Baja California, Mexico,<br />

January 17, <strong>2021</strong>. The small community<br />

has at least four different cemeteries<br />

generationally identified. The town lost<br />

most of its population after Hurricane<br />

Lester in 1992, the biggest storm the<br />

community has faced in its history.<br />

Since 2006, the community has lost 60<br />

members and has a population of 12<br />

today.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

MIGRATION, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND HISTORICAL MEMORY<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Sofia Aldinio<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 3

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Felipe and Olga drive to buy food<br />

for their goats in San Juanico, Baja<br />

California, Mexico, January, 23, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

The land is parched after no rain for<br />

three years, and the goats have been<br />

having a hard time finding the wild<br />

food that grows in the desert.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 5

PATH<br />

AWAY<br />

TENS OF THOUSANDS FLEE VIOLENCE,<br />

CLIMATE CHANGE, AND ECONOMIC<br />

COLLAPSE FOR NORTH AMERICA<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FIRST-PLACE WINNER<br />

By Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

Two months after Hurricanes Eta and<br />

Iota hit Central America in November<br />

2020, leaving 4.5 million victims of<br />

flooding and mudslides in their wake,<br />

11 thousand people gathered in San<br />

Pedro Sula, Honduras starting the<br />

first migrants’ caravan of the year heading<br />

towards the United States. <strong>2021</strong> began<br />

with one of the most significant migration<br />

waves of the last decade posing a difficult<br />

challenge for the new administration of<br />

President Joe Biden.<br />

The migrants’ crossing through gangcontrolled<br />

areas, deserts, and jungles<br />

is made even harder by the pandemic.<br />

International aid is scant, and many<br />

migrants’ shelters and charity kitchens<br />

closed their doors to avoid contagion.<br />

Thousands of migrants have reached<br />

Mexico while walking along its southern<br />

border with Guatemala, continuing the<br />

migration routes of the Gulf of Mexico, and<br />

the northern border with the United States to<br />

seek asylum. However, hundreds of families<br />

are expelled and returned to Mexico. Their<br />

asylum claims are denied with arguments<br />

based on Title 42, a U.S. statute that allows<br />

the expulsion of migrants from a country<br />

where a virus such as COVID-19 is present.<br />

This is their story.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Left: Lesbia Vanessa Bovadia, 35 years old,<br />

from Honduras, cries as she talks to a psychologist<br />

in a charity shelter in Tijuana, Mexico.<br />

After being separated from her children in the<br />

United States, she was deported to Mexico in<br />

2019. She doesn’t know where her children<br />

are, and she’s desperate to find them. The<br />

last time she saw them was in Chattanooga,<br />

Tennessee in 2018 before being arrested by<br />

the U.S. police.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 7

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Nicolò Filippo<br />

Rosso<br />

Guatemalan police officers take<br />

custody of a Honduran migrant<br />

who attempted to break the police<br />

barricade while driving a truck in<br />

Vado Hondo, Guatemala.<br />

January 18, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 9

Migration from the<br />

Phoenix<br />

Channel<br />

Islands<br />

Mexicali<br />

Guadalupe<br />

Hermosillo<br />

A<br />

Chihuahua<br />

G o l f o d e C a l i f o r n i a<br />

La Paz<br />

Culiacan<br />

Durango<br />

MEXICO<br />

Saltillo<br />

Ciudad Victoria<br />

Monterrey<br />

Zacatecas<br />

Aguascalientes San Luis Potos<br />

Tepic<br />

Leon<br />

Queretaro<br />

Guadalajara<br />

Morelia Pachu<br />

Colima<br />

Toluca<br />

Mexico<br />

Chilpancingo<br />

P a c i f i c<br />

Olga Marina Rodriguez<br />

Gonzalez holds her two<br />

babies while waiting for<br />

the cargo train known as La<br />

Bestia “The Beast.” People<br />

jump on the moving train to<br />

reach Northern Mexico, on<br />

their way to the United States.<br />

Coatzacoalcos, in Veracruz,<br />

Mexico. February 16, <strong>2021</strong>.<br />

Photo by Nicolò Filippo Rosso.<br />

O c e a n<br />

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Northern Triangle<br />

A last resort to stay alive<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

Little Rock<br />

ustin<br />

i<br />

ca<br />

City<br />

MEXICO<br />

Guatemala<br />

The significant increase<br />

in migration from<br />

Central America to the<br />

U.S. in recent years<br />

indicates rapidly deteriorating<br />

conditions<br />

in the region that have left people<br />

no choice but to flee in order to<br />

survive. The majority of migrants<br />

come from Honduras, Guatemala<br />

and El Salvador, together referred<br />

to as the Northern Triangle.<br />

Around 311,000 migrants<br />

from this region arrived in the<br />

U.S. between 2014 and 2020<br />

according to the Congressional<br />

Research Service. In June <strong>2021</strong>,<br />

US Customs and Border Protection<br />

(CBP) recorded almost 180,000<br />

Baton Rouge<br />

GUATEMALA<br />

San Salvador<br />

Jackson<br />

EL SALVADOR<br />

BELIZE<br />

HONDURAS<br />

Tegucigalpa<br />

Managua<br />

Havana<br />

San Jose<br />

Atlanta<br />

Montgomery<br />

NICARAGUA<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

Tallahassee<br />

Columbia<br />

migrants – including 15,000 unaccompanied<br />

minors and 50,000<br />

families – the highest monthly total<br />

in over 20 years. But given that<br />

one third of these migrants have<br />

crossed the border previously, the<br />

actual increase in migration may<br />

not be as high.<br />

“It’s one of the hardest decisions<br />

people are often making,” says<br />

Andani Alcantara Diaz, supervising<br />

attorney of removal defense for<br />

the Refugee and Immigrant Center<br />

for Education and Legal Services<br />

(RAICES) in Austin, Texas. “That’s<br />

why you see people go through<br />

really horrible things and still not<br />

leave for a while because they<br />

don’t want to leave their homes,<br />

their families, everything they<br />

know, behind. But at a certain<br />

point, it’s the only thing they can<br />

do to stay alive.”<br />

The main drivers of migration<br />

from the Northern Triangle are violence<br />

and socioeconomic insecurity,<br />

which frequently overlap, and are<br />

exacerbated by climate change.<br />

“Many migrants are fleeing<br />

gangs or other sorts of dangerous<br />

organizations that have harmed<br />

them and their families,” says<br />

Alcantara Diaz, “And they know<br />

they can’t go to the government,<br />

that the government in their countries<br />

is not going to protect them.”<br />

Many of these gangs originated<br />

in Los Angeles in the 1980s and<br />

were later deported back to their<br />

home countries in the region.<br />

Women and children are<br />

particularly vulnerable to violence,<br />

often within the home. Honduras<br />

and El Salvador have some of the<br />

highest rates of femicide worldwide.<br />

Endemic corruption means<br />

that the police are often involved<br />

and those responsible are not held<br />

to account. The threat of violence<br />

by both gangs and family members<br />

has led to a surge in unaccompanied<br />

minors arriving at the U.S.<br />

border since 2014.<br />

Socioeconomic drivers of migration<br />

include widespread inequality<br />

and poverty and pervasive lack<br />

CUBA<br />

JAMAICA<br />

Panama<br />

Bahama<br />

Islands<br />

Nassau<br />

Long Island<br />

G r e a t e r A n t i l l e s<br />

Caribbean Sea<br />

of work opportunities. With 40<br />

percent of the population under the<br />

age of 20, youth can either stay in<br />

precarious working conditions or<br />

try to seek opportunities elsewhere.<br />

Climate change has led to prolonged<br />

droughts and crop losses.<br />

The coffee industry has been hit<br />

hard by both an increase in the<br />

coffee leaf rust fungus and low<br />

international coffee prices, jeopardizing<br />

a critical source of seasonal<br />

income for over a million families.<br />

In addition, in 2020, the region<br />

was devastated by the COVID<br />

pandemic and back-to-back category<br />

4 Hurricanes Eta and Iota,<br />

which displaced over 500,000<br />

people, leaving many homeless<br />

and without access to clean<br />

drinking water. According to the<br />

World Food Programme, approximately<br />

eight million people are<br />

facing hunger, including a quarter<br />

with emergency levels of food<br />

insecurity. Almost 15 percent of<br />

people surveyed in January <strong>2021</strong><br />

reported plans to migrate, up eight<br />

percent from 2018.<br />

A Migrant Family’s<br />

Journey<br />

Angel Antonio Mejia Gonzales,<br />

from Danli, Honduras, felt he<br />

had no choice but to leave. The<br />

33-year-old and his wife, Olga<br />

Marina Rodriguez Montoya, 27,<br />

had both been affected by violence<br />

and wanted to protect their<br />

children. Mejia Gonzales is eager<br />

to work but says there were no<br />

prospects for work in Honduras.<br />

And Hurricanes Eta and Iota took<br />

what little they had.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 11

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS<br />

Photo by Joshua Rashaad<br />

McFadden<br />

After the last speech at the<br />

Commitment March Rally on<br />

August 28, 2020, thousands<br />

of people flooded the streets of<br />

Washington, D.C., to protest<br />

police brutality in America.<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 15

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Several consistent themes arise across<br />

the thousands of images documenting<br />

the last year of racial justice<br />

protests in the United States— the<br />

raised Black power fist; a surge of<br />

civilian bodies facing off against<br />

a line of stony-faced police forces; eyes<br />

raised to the camera in triumphant challenge<br />

of the powers that be. Each of these<br />

poignant moments draw from long histories<br />

of photography on the American struggle<br />

for justice within a country whose deeply<br />

embedded racism spans centuries built of<br />

settler colonization and the enslavement of<br />

Black people.<br />

An especially horrific part of that long<br />

history of racial terror and subjugation in<br />

America is the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre<br />

of Black residents by a white mob.<br />

While many Black Americans have long<br />

held the memory of that deadly night and<br />

the several preceding years of white mob<br />

violence that erupted across the nation,<br />

few photographs exist to bear ongoing<br />

witness to the death and destruction. In the<br />

decades since, however, Black Americans<br />

have utilized the camera’s evidentiary<br />

power as a tool in the twin struggles to<br />

humanize Black lives and depict racial<br />

injustice. The evisceration of Tulsa’s prosperous<br />

Black community and the 2020<br />

racial justice protests that represent the<br />

largest social justice movement in U.S.<br />

history are separated by nearly 100 years,<br />

serving as troubling markers of how little<br />

progress has been made on this long road<br />

to justice. Yet, the influx of visual storytelling<br />

by those whose lives are held in the<br />

balance and social media’s access to a<br />

rapt global audience offers new hope that<br />

justice might yet be realized.<br />

Since Black Lives Matter’s 2013 beginnings<br />

as a hashtag following the 2013<br />

shooting death of Black teenager Trayvon<br />

Martin, the movement gained steam as<br />

both a social media campaign and a<br />

series of national protests in the wake of<br />

each Black person killed by police brutality.<br />

It’s vital to understand how much this<br />

movement (and many other contemporary<br />

social justice efforts) owes to the wide<br />

circulation of visual evidence online. While<br />

such egregious acts of racial violence and<br />

police brutality have been rampant since<br />

the advent of American policing, it is the<br />

increasing presence of digital cameras that<br />

have ushered in an era where racism can<br />

be documented and therefore demand further<br />

reckoning. As BLM builds on the visual<br />

rhetoric of Civil Rights Movement photography,<br />

the relationship between street-level<br />

activism and the power of the camera is<br />

increasingly revealed.<br />

The collection of 23 photographs on<br />

these pages is drawn from over 500<br />

images submitted by photographers who<br />

answered the call to share their visual<br />

interpretations of the Long Road to Justice.<br />

Importantly, the work is primarily made<br />

by Black photographers whose lived<br />

experiences of racial injustice and respect<br />

for Black lives is tangibly felt across the<br />

photo essay. From Brian Branch-Prices’s<br />

intimate look at Black musicians to Kenechi<br />

Unachukwu’s We Still Here, a picture of<br />

Black resilience emerges. Donald Black<br />

Jr.’s loving ode to Black childhood symbolizes<br />

exactly what we fight for: a future<br />

where the threat of police brutality against<br />

our children, our mothers, our fathers and<br />

brothers is a thing of the past.<br />

The work to realize that future, however,<br />

is far from over. Even as these images of<br />

Black life compel the world to recognize<br />

the shared humanity of all people, there<br />

remains a stark disconnect between the<br />

realities visualized by our photography<br />

and the widespread realization of social,<br />

political, and economic reform. The<br />

struggle for racial justice continues and we<br />

lift our cameras as we steady our resolve,<br />

ready to meet the call wielding our choice<br />

of weapons.<br />

—Tara Pixley<br />

Program Credits<br />

Chair:<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Jurors:<br />

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn<br />

Lisa DuBois<br />

Anthony Barboza<br />

Eli Reed<br />

Jamel Shabazz<br />

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Best-of-Show Award<br />

Donald Black Jr.<br />

A Day No One Will Remember<br />

A collection of images created by Donald<br />

Black Jr. over the past 10 years. After returning<br />

home to Cleveland, Ohio, he started creating<br />

images that only an insider could see<br />

and began making images that represented<br />

his perception of his reality. Seeing himself<br />

and where he came from has influenced<br />

an obsession to photograph children in his<br />

community.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 17

FROM TULSA TO MINNEAPOLIS: PHOTOGRAPHING THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE<br />

Above<br />

Photographer: Titus Brooks Heagins<br />

Exhibit Title: Where the Sidewalk Ends<br />

This project represents a visual dialog<br />

that interrogates the lives of those who<br />

live in the margins of society.<br />

Caption: Brittany and Brianna<br />

Right top<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: Rhythm and Praise, an<br />

Epic Journey<br />

This project reflects the expressions,<br />

thoughts and actions of a people, of a<br />

culture and of a folk who love to sing,<br />

dance, shout, give, teach, preach, cut a<br />

step all in the name of gospel music.<br />

Caption: Percy Bady, Newark, New<br />

Jersey<br />

Right below<br />

Photographer: Teanna Woods Okojie<br />

Exhibit Title: Black Boy Joy<br />

Black Boy Joy is a series of multiple<br />

images spanning from 2013 to <strong>2021</strong><br />

depicting young African youth and<br />

young men in various environments<br />

experiencing pure joy.<br />

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Above<br />

Photographer: Brian Branch-Price<br />

Exhibit Title: BLM: The Third<br />

Expressing the frustrations of an oppressed<br />

community reacting to social injustices, economic<br />

apartheid, Jim Crow, over-policing,<br />

lynching, inhumanity, during peaceful and<br />

confrontational protest in New York, New<br />

Jersey, Philadelphia, Richmond, and D.C.<br />

Caption: Livia Rose Johnson, 20, march<br />

organizer during a Justice for George Floyd<br />

protest and rally in New York on June 4, 2020<br />

Left<br />

Photographer: Raymond W. Holman, Jr.<br />

Exhibit Title: COVID-19 in Black America<br />

Environmental portraits of Black and brown<br />

skin people with first-hand experience of<br />

COVID-19 – having recovered, lost family<br />

members, been mentally challenged by<br />

social isolation, and figuring out how to<br />

adjust and make a new pathway.<br />

Caption: A Princeton University student<br />

experiencing a year of online classes and<br />

isolation due to COVID-19, but becoming a<br />

stronger human being through this challenge.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 19

Interview<br />

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ<br />

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York-based photographer<br />

whose career spans over 25 years. His<br />

work has been published in National Geographic,<br />

The New York Times <strong>Magazine</strong>, Mother Jones,<br />

Newsweek, New York <strong>Magazine</strong> and others. He<br />

teaches at NYU and the International Center<br />

for Photography (ICP), among others, and has<br />

published several books including, more recently:<br />

Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987<br />

and LAPD 1994. Below is an excerpt from our<br />

conversation, edited for clarity.<br />

By Caterina Clerici<br />

Caterina Clerici: Can you tell us about<br />

your background and how you got<br />

started in photography?<br />

and then dropped out and then got into<br />

the drug scene, started doing heroin,<br />

selling heroin, all that bad boy stuff. I<br />

went to Rikers Island. First time I went in, I<br />

was 17 years old. The second time I was<br />

20, and I was a much tougher guy than<br />

when I first went in. Rikers Island is not<br />

a place that I can even describe to you.<br />

How horrible that place is, that’s a whole<br />

other story.<br />

However, I came out at a very interesting<br />

time because I felt the need to change<br />

and those were the times of affirmative<br />

action, the only way for most young people<br />

to go to college without the ugly bank<br />

loans we have today. Through education<br />

I got myself together: got off methadone<br />

at 26, got my GED and studied graphic<br />

arts technology at the New York City<br />

Technical College in downtown Brooklyn.<br />

In 1980, I came out of school — first one<br />

to go to college in my family — and got<br />

a job in the printing business. You would<br />

send us your chromes, and we would<br />

make negatives, make plates and put<br />

them on a printing press. I learned a lot<br />

about color and printing and that helped<br />

my photography later on.<br />

I was making a lot of money in ‘80,<br />

‘81, doing all those big ads you see<br />

on the front pages of magazines, but I<br />

found myself going back down a rabbit<br />

hole, working 50, 60 hours a week. It<br />

was a great experience, but I was really<br />

unhappy. So I quit my job. My mother<br />

was very upset. I went back to driving<br />

a cab (taking photos that made up Taxi:<br />

Journey Through My Windows 1977-<br />

1987) and worked with a friend who had<br />

a truck and an art moving business.<br />

One day we delivered to a gallery in<br />

Soho where Larry Clark was laying his<br />

whole life’s work up on the wall. I went<br />

up to him as if he was Jimi Hendrix, like,<br />

“Oh, man! I really want to do what you<br />

do!” and he said: “Just go make pictures.”<br />

That’s all he said to me.<br />

I went to ICP and started assisting in<br />

the dark room, cleaning up the cibachrome<br />

lab. Then they gave me a scholarship<br />

and my life changed. I was schooled<br />

by some of the greatest Magnum photographers:<br />

Gilles Peress, Susan Meiselas,<br />

Eugene Richards, Alex Webb, Raymond<br />

Depardon, Sebastiao Salgado. The way<br />

I work is the way they work. For weeks,<br />

months and years. Anything personal is<br />

going to take me years. I’m just coming<br />

off following Mexican migrants throughout<br />

the USA for 10 years.<br />

I think about photography in time, and<br />

I always felt great work takes a lot of it.<br />

And, for me, it was always self-initiated.<br />

There were no editors, no one telling me<br />

Joseph Rodriguez: I was born and<br />

raised in Brooklyn in 1951. I grew up<br />

where I live right now, Park Slope, but it<br />

was South Brooklyn then. And you know,<br />

the Italian American history in New York<br />

was very strong. It was a very mafioso<br />

neighborhood and I’m not lying — we<br />

had the Gowanus Canal and it was not<br />

unusual for us to see floating bodies… It<br />

was pretty much like the old Sicilian way.<br />

In my Catholic school there were<br />

only about 400 or 500 of us. There was<br />

one Black kid and one Puerto Rican kid:<br />

me. The other kids were all mostly from<br />

Genoa, in Italy. Every single parent who<br />

lived close by used to grow grapes in<br />

the backyard and you would stop by to<br />

try their wine. It was very old school.<br />

But then the drugs came, and that’s what<br />

brought a lot of the same problems you<br />

have in so many other places.<br />

I lost my way… got into high school<br />

A young 18th Street Gang member being arrested. At the time this photo was taken the ATF (Arms Tobacco and<br />

Firearms) were working with LAPD to try and take down one of the most notorious gangs in Los Angeles. The aim<br />

was also to get as many guns off the streets as possible. Photo by Joseph Rodriguez from LAPD 1994.<br />

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

what to do. We just had that practice,<br />

that discipline, which also brings a lot<br />

of anxiety because you’re swimming<br />

upstream and you’re always alone. The<br />

practice is mapping out a story, which<br />

then turns into something longer — like<br />

when I went to LA in 1992 to photograph<br />

gangs and I’m still revisiting that project<br />

some 20 years later.<br />

CC: Can you tell us how your project<br />

on gang violence in LA started, how it<br />

evolved, and the challenges you faced?<br />

JR: When the Rodney King uprising<br />

happened, immediately I wanted to<br />

go, because I was missing America<br />

(Rodriguez was living in Europe at the<br />

time) and I understand the urban narrative,<br />

no matter which city it is — Chicago,<br />

Miami, New York, LA. I couldn’t do much<br />

research while I was living in Europe,<br />

because it wasn’t like now where everything’s<br />

online, but one thing I did was listen<br />

to music: all this gangsta rap, Eazy-E,<br />

Tupac, Dre, N.W.A., Public Enemy. The<br />

rhymes they were spitting out were the<br />

newspapers of the streets. So I was listening<br />

to guys like this Chicano rapper Kid<br />

Frost, who’s totally East LA, and I was like<br />

“Ok, I gotta go there.”<br />

I flew in the middle of the night from<br />

Stockholm to LA and arrived in my hotel<br />

room. I didn’t know where I was going,<br />

I had no connections and LA is huge!<br />

So I grabbed three newspapers, turned<br />

on the news and of course there was a<br />

funeral and a drive-by shooting every<br />

minute.<br />

There was a lot of ground to cover,<br />

so I stayed five weeks and worked<br />

really hard. No sleep, just worked and<br />

drove around, from one neighborhood<br />

to another, also with the cops doing the<br />

gang unit. But I knew our history already.<br />

I began interviewing African-American<br />

families in Watts, asking what was the<br />

difference with the riots in 1965, in the<br />

era when Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy<br />

were assassinated and there was a lot<br />

of city streets burning. The conversation<br />

began and it opened up doors, and I<br />

realized I wasn’t interested in just the<br />

guns or the people dying. This was a<br />

generational story that went back three or<br />

Waiting for a fare outside 220 West Houston Street, an after-after-hours club. New York 1984. Photo by Joseph<br />

Rodriguez from Taxi: A Journey Through My Window 1977-1987.<br />

four generations. That’s when I really felt<br />

the power of this story.<br />

I went back to Stockholm and we published<br />

what we could. I applied for an artist<br />

grant there, and then I moved to LA in<br />

September of ‘92. It was hard, I had left<br />

the kids behind and just kept flying back,<br />

trying not to be the absentee father that I<br />

was. But that was the path I was on.<br />

The gang project was very hard to<br />

do and I paid the psychological price<br />

for it, in terms of PTSD. At least eleven<br />

kids are dead, in the East Side Stories:<br />

Gang Life in East L.A. book. Children<br />

were dying and parents were telling me<br />

I needed to tell this story. Plus, sometimes<br />

people thought I was an undercover cop.<br />

I showed them my Spanish Harlem book<br />

and my National Geographic stories to<br />

prove that I wasn’t a cop, but paranoia<br />

runs deep in the hood. That hung over my<br />

head for a while — until the book was<br />

published — and I was going to quit the<br />

project, I felt I couldn’t handle it.<br />

I also had guys come say to me: “Yo,<br />

man, I’m about to go do a hit, you can<br />

come and just take pictures.” This is ethics.<br />

I said: “Look, I go with you, I photograph<br />

you doing this scene. Detectives<br />

come, they find out who’s who, they<br />

take my film and they use the evidence<br />

against you.” Some of the gang members<br />

were 16 years old; they didn’t know how<br />

the law worked. They didn’t understand<br />

what a camera could do. They were so<br />

enamored by their vanity and Hollywood<br />

influence. With a camera comes a lot of<br />

responsibility.<br />

CC: How did your surroundings while<br />

growing up influence your practice and<br />

your understanding of photography, as<br />

well as your mission as a “humanist”, as<br />

you often define yourself?<br />

JR: I grew up with my mother and her<br />

sisters, and there were no men in my family.<br />

My stepfather was a dope fiend who<br />

died on the streets. There were a lot of<br />

not nice things growing up, and that was<br />

very tough for me.<br />

One thing I remember is that my mom<br />

would sit with her sisters in a very old<br />

school, Italian way, they would have their<br />

coffee and talk about the men. I would<br />

hear these stories — it was unbelievable<br />

— of abuse and cheating, and those references<br />

helped me develop a feminine eye.<br />

I’m always asking myself: “Why did<br />

this photographer go photograph a gangster<br />

with guns, bullets and drugs, but then<br />

didn’t photograph a mother at the same<br />

time, or the struggling parent?” That’s<br />

always been very important in my work. I<br />

didn’t always go for the guns.<br />

“Raised in violence, I enacted my own<br />

violence upon the world and upon myself.<br />

What saved me was the camera, its ability<br />

to gaze upon, to focus, to investigate,<br />

to reclaim, to resist, to re-envision.” That<br />

quote is from my journal. That’s how I<br />

got here, that’s where this goal comes<br />

from. That’s why I went back for East Side<br />

Stories (Rodriguez’s long-term project<br />

about gang violence in LA, shot between<br />

1992–2017.)<br />

Continued on page 70.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 21

But before delving into how documentary<br />

photography is evolving, it is essential<br />

to first address the fight to change<br />

the internal practices and structure of the<br />

photo industry itself.<br />

One of the biggest problems in<br />

photography is the widespread percep-<br />

Years ago,<br />

tion among audiences that photographs<br />

during an artist talk at a journalism<br />

conference, I stated that I the extent to which a photographer’s<br />

don’t lie. Most people don’t understand<br />

don’t believe documentary photographs<br />

create social change. A consume. This knee-jerk assumption of<br />

personal biases impact the images we<br />

colleague stood up and interrupted my objectivity allows audiences to accept<br />

talk to disagree with me. Our impromptu an image as truth: forming hard-andfast<br />

opinions about events and cultures.<br />

debate--across an audience of photographers<br />

and journalism students--exemplifies Without critical assessment from the viewers,<br />

the photographer has tremendous<br />

an important dialog within our industry<br />

that is pushing the boundaries of how power over the value viewers assign to<br />

photography is created and used. Our the lives of the individuals pictured. Such<br />

power and representation have plagued<br />

the industry since the advent of photography<br />

as a medium. Recent momentum<br />

in acknowledging and changing these<br />

practices prompted the formation of<br />

collectives such as Women Photograph,<br />

MFON, Diversify Photo, Ingenious<br />

Photograph, and the Authority Collective,<br />

to name a few. Meaningful reflection<br />

about representation, connection, and<br />

accountability are imperative starting<br />

points for anyone assigning, publishing,<br />

Photography &<br />

By Emily Schiffer<br />

disagreement hinged on different definitions<br />

of what “social change” looks like<br />

and means. I was asserting that images<br />

create awareness--which unreliably<br />

evokes empathy, shifts mindsets, and<br />

inspires action. He was arguing that<br />

empathy is change. We were both right.<br />

Differentiating between raising awareness,<br />

fostering empathy, inspiring action,<br />

and changing conditions enables photographers<br />

to precisely define their goals<br />

and approaches for individual projects.<br />

A whole world opens up when<br />

we think of images as the start<br />

of a creative process—rather<br />

than the end goal.<br />

unchallenged authority creates a dangerous<br />

paradigm. Historically, photographers<br />

have been overwhelmingly white<br />

and male, which means they produced<br />

images of cultures, communities, and<br />

people that were not familiar to them.<br />

On top of that, editors, curators, critics,<br />

and other industry gatekeepers have<br />

also historically been white and male,<br />

which further normalizes the white male<br />

gaze within the industry writ large, and<br />

silencing other perspectives. This set-up<br />

causes glaring omissions in documentary<br />

narratives. Practically speaking,<br />

omissions amount to erasure, which is a<br />

quintessential tactic of colonialism and<br />

oppression. Despite important changes<br />

in who is able to access the profession,<br />

and in how we think about photography,<br />

statistics show that the demographics of<br />

the industry remain largely unchanged.<br />

In 2020, 80% of A1 images in leading<br />

U.S. and European newspapers were<br />

created by male photographers. Issues of<br />

exhibiting, or creating photographs, let<br />

alone those attempting to create social<br />

change through photography.<br />

Sometimes, viewers need to physically<br />

see the errors in the dominant narrative<br />

in order to shift their mindset. Artists such<br />

as Alexandra Bell, Wendy Red Star,<br />

and Tonika Lewis Johnson visualize the<br />

crisis of biased representation, enabling<br />

viewers to reflect on their perceptions<br />

of self and others. Bell redacts racist<br />

language in New York Times articles and<br />

sometimes changes the imagery to reflect<br />

a more accurate depiction of the facts.<br />

She then wheatpastes the before and<br />

after versions of the articles onto outdoor<br />

public walls: simultaneously holding the<br />

media accountable, and forcing viewers<br />

to confront their complacency when<br />

consuming media. Similarly, Red Star<br />

annotates photographs of Crow chiefs,<br />

originally taken by Charles Milton Bell in<br />

1880. Red Star uses red ink to provide<br />

historical and contextual information,<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Dawnee LeBeau. From Women of the<br />

Tetonwan, a portrait project celebrating the matriarchs<br />

of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. <br />

Winona Kasto is one of our Lakota Lolihan' (cooks).<br />

It's a great honor to be able to offer food as nourishment<br />

and healing, especially at ceremonies and<br />

community events.<br />

with individuals directly impacted by the<br />

issues their work addresses. Still, for others<br />

who photograph solo, like Dawnee<br />

LeBeau, an ongoing and deep community<br />

dialog dictates what is created and<br />

shared. It is worth noting that all of the<br />

aforementioned photographers identify<br />

as part of the communities they document.<br />

Even people depicting their own<br />

cultures need accountability, and ceding<br />

power enriches photographic work.<br />

Listening, critical discourse, and reflection<br />

Social Change<br />

on one’s own biases are even more vital<br />

for outsiders.<br />

thereby informing the viewer and commenting<br />

on non-Indigenous people’s lack<br />

of knowledge about Indigenous culture<br />

and history. Aware of how profoundly the<br />

media impacts our sense of self, Johnson<br />

created Englewood Rising, a communityled<br />

billboard campaign created and<br />

paid for with funds raised by Englewood<br />

residents and activists to, “showcase<br />

Englewood’s everyday beauty and<br />

counter its damage-centered narrative.”<br />

Created by the community, for the community,<br />

and in the community, this wildly<br />

popular project demonstrates how well<br />

someone from the community can portray<br />

other members within it.<br />

Discussions about representation<br />

and whether or not a solo perspective is<br />

always desirable have prompted photographers<br />

to share authorship and power<br />

in the image-making process. More<br />

horizontal approaches sometimes take<br />

the form of a collective voice, composed<br />

of many professional photographers, as<br />

is the case with Kamoinge (founded in<br />

1963), a collective working to “HONOR,<br />

document and preserve the history and<br />

culture of the African Diaspora with<br />

integrity and insight for humanity through<br />

the lens of Black photographers.” Other<br />

artists, like Brenda Anne Kenneally, facilitate<br />

decade-long photography workshops<br />

With the politics of representation<br />

fresh on our minds, and<br />

the raising of awareness as a<br />

baseline, we will look at examples<br />

of photographers leading<br />

our industry in a more responsible,<br />

and impactful direction.<br />

Whether making images collaboratively,<br />

using them to create conversations,<br />

creatively installing them in communities,<br />

or amplifying existing grassroots<br />

organizing, these projects engender<br />

active engagement from both the people<br />

impacted by these issues and the viewers<br />

seeing these projects--even when there is<br />

not an easy or clear solution.<br />

More →<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 23

Photography & Social Change<br />

Projects<br />

That Inspire<br />

Introspection<br />

and<br />

Challenge<br />

Oppressive<br />

Narratives<br />

Ariana Faye Allensworth<br />

Staying Power<br />

Ariana Faye Allensworth’s<br />

background in social work,<br />

urban studies, African<br />

American studies,<br />

and education enables her to<br />

deconstruct power imbalances<br />

in the photo industry.<br />

Her latest project Staying<br />

Power, implements her critique<br />

of how photography is<br />

taught, and how narratives are<br />

constructed and consumed.<br />

Staying Power is “a collaborative,<br />

multidisciplinary art and research project<br />

celebrating the people’s history of New<br />

York City public housing. The project<br />

offers counter-narratives to the stereotypes<br />

surrounding the New York City<br />

Housing Authority (NYCHA) through<br />

the lens of residents raised and living in<br />

NYCHA.”<br />

The project emerged out of<br />

Allensworth’s collaborative work at the<br />

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP):<br />

visualizing injustice by mapping open<br />

data, collecting oral histories, producing<br />

storytelling projects in collaboration<br />

with tenants, facilitating mutual aid, and<br />

researching real estate speculation and<br />

corporate landlordism.<br />

At AEMP, Allensworth worked closely<br />

with residents displaced by the demolition<br />

and downsizing of public housing.<br />

New York City, home to the largest public<br />

housing stock in the United States, is<br />

privatizing and defunding many public<br />

housing programs, a radical shift in<br />

how these programs are managed and<br />

operated. “It’s an important moment to<br />

document public housing reform, and<br />

to create room for people’s narratives,”<br />

explains Allensworth. The dominant<br />

‘failed public housing’ narrative stood<br />

in stark contrast to the breadth of lived<br />

experiences residents described.<br />

Housed online, Staying Power is a<br />

platform for publishing, discussing, and<br />

presenting the NYCHA community’s<br />

histories. The content is also available<br />

through an open-ended series of booklets<br />

and postcards, distributed to subscribers<br />

through the postal service.<br />

The project explores how this community<br />

creates, cares for, and<br />

builds their own archives.<br />

“Memory is a valuable historical<br />

resource,” explains<br />

Allensworth. “Staying<br />

Power explores how<br />

photography, ephemeral<br />

and personal collections<br />

of objects, and interviews<br />

with residents can offer<br />

alternative modes of knowledge<br />

that retell the public housing story. The<br />

project positions residents as archivists<br />

and storytellers.” Allensworth’s goal is to<br />

refute stereotypes that eclipse people’s<br />

lived experiences, and assert that all residents<br />

are worthy of inclusion in NYCHA<br />

history.<br />

To gather material, Allensworth<br />

facilitated photography workshops,<br />

conducted long-form oral histories, and<br />

photographed ephemera. Teaching<br />

photography as a way of collaboratively<br />

building narratives poses a challenge: on<br />

the one hand, taking someone’s creativity<br />

seriously by helping them develop<br />

their craft is the ultimate form of respect.<br />

On the other hand, traditional photoeducation<br />

practices—which literally teach<br />

how to see—undermine the message that<br />

Image by Ariana Faye Allensworth. A poster created<br />

for Staying Power featuring an image of Michael Casiano,<br />

a resident of LaGuardia Houses on the Lower<br />

East Side of Manhattan.<br />

everyone’s perspective and story is valid.<br />

Allensworth didn’t want her aesthetic<br />

preferences to influence the work residents<br />

created. She structured her workshops<br />

using the “Photo Voice” model,<br />

inviting participants to create visual<br />

answers to questions about their public<br />

housing experience. Instead of focusing<br />

on aesthetics, the group discussed the<br />

messages the images delivered, and critiqued<br />

the artists’ visual communication.<br />

Similarly, Allensworth’s method of<br />

collecting oral histories positioned the<br />

narrator to author their own story: “I<br />

don’t show up with a predetermined set<br />

of questions, so they’re not reduced to<br />

whatever container I create for them.<br />

They decide what it is that they want to<br />

put on record.”<br />

Though created primarily for NYCHA<br />

residents, Staying Power is also an important<br />

resource for educators, activists, and<br />

policy makers looking to counter erasure,<br />

claim space, and amplify residents’<br />

experiences without filtering them through<br />

a third party lens.<br />

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> and receive the full<br />

84-page version in print and digital<br />

$25.00* for two issues/year<br />

Includes print and digital<br />

*Additional costs for shipping outside the US.<br />

Subscribe to <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine and get the best of<br />

global documentary photography delivered to your<br />

door, and to your digital device, twice a year. Each<br />

issue presents outstanding photography from the<br />

Social Documentary Network on topics as diverse<br />

as the war in Syria, the European migration crisis,<br />

Black Lives Matter, the Bangladesh garment industry,<br />

and other issues of global concern.<br />

But <strong>ZEKE</strong> is more than a photography magazine.<br />

We collaborate with journalists who explore<br />

these issues in depth —not only because it is important<br />

to see the details, but also to know the political<br />

and cultural background of global issues that require<br />

our attention and action.<br />

Click here to find out how »<br />

www.zekemagazine.com/subscribe<br />

Contents of <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2021</strong> Issue<br />

Awake in the Desert Land<br />

Photographs by Sofia Aldinio<br />

Path Away<br />

Photographs by Nicolò Filippo Rosso<br />

From Tulsa to Minneapolis: Photographing the<br />

Long Road to Justice<br />

Photographs by 27 Black photographers documenting this<br />

extraordinary time in American history<br />

The Emptying of the Andes<br />

Photographs by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Migration from the Northern Triangle<br />

by Daniela Cohen<br />

Interview with Joseph Rodriguez<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

Photography & Social Change<br />

by Emily Schiffer<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Edited by Michelle Bogre<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 25

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

‘Tia’ (aunt) Sibilla in her hut<br />

in the village of St Martin de<br />

Porres, 15,000 feet above the<br />

sea level, in Peru.<br />

The Emptying of the Andes<br />

By Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 27

There is a very quiet and subtle<br />

migration taking place in Peru. It is a<br />

phenomenon of “rural-urban migration”<br />

that has continued incessantly<br />

for years, and is emptying the Andes<br />

of people who are leaving their<br />

lands under the illusion of a better future in<br />

the big cities—Lima, Arequipa, Chimbote.<br />

Many young people have escaped from<br />

peasant life, only to end up in the favelas<br />

of these cities, with no light, no gas,<br />

nor running water. This migratory movement,<br />

which is emptying the Andes of a<br />

population that will end up in the slums, is<br />

referred to as “invasions,” because of the<br />

unstoppable number of arrivals.<br />

This photographic project by Italian<br />

photographer Emiliano Pinnizzotto follows<br />

the stories both of those who remain in<br />

their ancestral homes in the mountains, and<br />

those who left for the big city and found<br />

themselves passing from an imagined<br />

dream into a real nightmare. The Emptying<br />

of the Andes in an attempt to give voice<br />

to a little-known story that in the next few<br />

years will empty the mountains of native<br />

people and culture and fill the cities with<br />

those seeking a better life but often find<br />

disappointment instead.<br />

28 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

Photo by Emiliano Pinnizzotto<br />

Two women come back home with<br />

their sheep after a day of pasture.<br />

Grazing sheep is one of the main<br />

activities in the mountains. Sheep<br />

are raised principally for milk and<br />

wool and for their meat.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 29

BOOK<br />

REVIEWS<br />

EDITOR: MICHELLE BOGRE<br />

I CAN MAKE YOU FEEL<br />

GOOD<br />

By Tyler Mitchell<br />

Prestel, 2020<br />

208 pages | $60<br />

I<br />

Can Make You Feel Good, Tyler<br />

Mitchell’s second monograph,<br />

evidences and envisions contemporary<br />

Black joy. His work, which reframes<br />

Blackness through portraits that challenge<br />

prevailing racial stereotypes,<br />

investigates the question: What does the<br />

pursuit of happiness look like for Black<br />

Americans?<br />

Mitchell chronicles unguarded<br />

moments of tenderness, tranquility, and<br />

bliss among individual and intimate<br />

clusters of young Black adults. Dramatic<br />

silhouettes of sumptuously textured clothing<br />

are interspersed with soft-focused<br />

sensual gestures of gentle affection.<br />

With his cinematic eye and deft use of<br />

scale, composition, and perspective, he<br />

animates a fluid compilation of full bleed,<br />

mostly double-page spreads.<br />

Mitchell, who was included in the<br />

Aperture publication and exhibition, The<br />

New Black Vanguard, pushes the conventions<br />

of race, beauty, gender and power.<br />

Aware of, and indebted to, predecessors<br />

including Roy DeCarava, Gordon<br />

Parks, Jamel Shabazz and 19th century<br />

scholar, abolitionist and orator, Frederick<br />

Douglass, he and his contemporaries<br />

embrace the role of the Black body and<br />

Black lives as subject matter. They expand<br />

the visual culture conversation by documenting<br />

and challenging their realities of<br />

presence, absence, invisibility, appropriation,<br />

desire, and objectification.<br />

Mitchell’s images are subversive in<br />

their disruption of what writer Junot Diaz<br />

coins as the ‘default whiteness’ of our<br />

American society. They are transgressive<br />

in their assertion of a reality beyond<br />

conventional representation. The wraparound<br />

cover image is an apt example of<br />

Mitchell’s intentional tableaux: It shows<br />

five young shirtless men, three of which<br />

face away from the camera with heads<br />

bent, another is partially seen, his face<br />

in profile, gazing somewhat pensively<br />

across a flowering meadow to the edge<br />

of a tree-lined woods. The fifth person,<br />

and the only one facing the camera, has<br />

his face in shadow as he seemingly tightens<br />

the black belt at his waist. A thick,<br />

intertwined chain of silver metal catches<br />

the available light and grabs the attention<br />

of the viewer. A white string of cotton is<br />

tied as a single, loose bracelet on the<br />

wrist of his active hand. The choice of<br />

adornment and fashion accessory could<br />

be codifiers of modes of bondage and<br />

tools of slavery, and intersect with the<br />

understated but obvious designer labels<br />

of Valentino jeans (which retail for close<br />

to $1000) and Ben Sherman underwear<br />

(a fashion brand noted for attracting<br />

youth culture).<br />

Images of leisurely<br />

picnics are sequenced with<br />

people at play, frolicking<br />

and actively engaging with<br />

hula hoops, skateboards,<br />

jump ropes, and a kite.<br />

Mitchell acknowledges his<br />

reference to Tamir Rice, the<br />

12-year-old Black boy shot<br />

in a Cleveland park in 2014<br />

while carrying a toy gun.<br />

Mitchell also reframes the<br />

connotation of the hoodie,<br />

following its presence in<br />

the 2012 killing of 17-yearold<br />

Trayvon Martin. Two<br />

images purportedly use the<br />

same man wearing a plush<br />

cotton, powder-blue hooded<br />

sweatshirt while lying on<br />

a wooden floor. The first<br />

features him face down<br />

framed in a horizontal position with his<br />

open-palmed hands interlaced behind his<br />

back. In the second, he is face-up, with<br />

his head, shoulders and arms filling the<br />

bottom of the frame, his hands tentatively<br />

holding the soft hood, a wide-eyed listful<br />

expression, looking just above the gaze<br />

of the viewer. Both images imply the<br />

notion of an arrest and a mug shot.<br />

A final example of Mitchell’s purposeful<br />

challenge to codified visual language<br />

is a vertical image of a man standing<br />

in front of a peeling red-painted cement<br />

wall. He wears flowing white pants<br />

spilling over sleek brown leather loafers.<br />

A green fabric sac, is held in hand, a billowing<br />

bright yellow piece of silk is hung<br />

with clothespins from black electrical<br />

cording suspended above, obscuring his<br />

head and torso.<br />

This bold abstraction of Pan African<br />

colors is perhaps a nod to poet, playwright,<br />

and activist, Amiri Baraka, who<br />

saw Black beauty as an act of justice.<br />

His poem, Why Is We Americans?<br />

proclaims, “What is the use of being<br />

ethereal and being escapist and romantic?<br />

Take the words and make them into<br />

bullets. Take the words and make them<br />

do something.” Tyler Mitchell’s images<br />

create visual text to explode imagination<br />

and claim sovereignty.<br />

—J. Sybylla Smith<br />

©Tyler Mitchell.<br />

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>

OUR TOWN<br />

by Michael von Graffenried<br />

Steidl, <strong>2021</strong><br />

121 pages | $50<br />

“<br />

The only way to achieve realistic<br />

pictures is to steal them,” says<br />

Swiss photographer Michael<br />

von Graffenried (MvG as he calls<br />

himself), whose most recent book, Our<br />

Town, illustrates both the art of the steal<br />

and MvG’s chosen path bringing people<br />

together, or not. In Our Town, MvG catalogs<br />

the divisions of racism in a small<br />

town in America by photographing who<br />

he observes—whites with whites and<br />

Blacks with Blacks. There are common<br />

moments that chronicle people together:<br />

high school events, sports, political gatherings,<br />

a wedding, a barbershop and<br />

a strip bar. In the latter photograph, a<br />

white male in erotic contact with a Black<br />

dancer sadly illustrates the disparity that<br />

is less blatantly represented throughout<br />

Our Town.<br />

MvG prefers using an old rotating lens<br />

35mm Widelux film camera which has a<br />

140 degree wide angle view because,<br />

he says, he can hold the camera next to<br />

his chest, and take photos without looking<br />

through the viewfinder. “Today, photography<br />

is no longer real...People know you<br />

are coming and are putting on a show.<br />

They are never themselves. That’s why<br />

I use this camera. You can take photos<br />

without looking through the viewfinder<br />

and nobody notices when you are actually<br />

pressing the shutter button. It’s the<br />

only way to achieve realistic pictures,” he<br />

said in a 2010 interview with Hans Ulrich<br />

Obrist, held in the Serpentine Gallery,<br />

Kensington Court, London.<br />

Holding a large Widelux camera at<br />

chest level does not make a photographer<br />

invisible. It does increase MvG’s opportunity<br />

to steal a picture by circumventing the<br />

scene-altering effect of asking permission<br />

to make a picture. MvG’s mandate to<br />

bring people together seems to be related<br />

to his camera’s ability to register everything<br />

within its field of view. With the use<br />

of this slow-tech camera technique, he<br />

slices a story from his chosen environment<br />

with an impressive mastery.<br />

In 2006, MvG began his Our Town<br />

project for the 300th anniversary of the<br />

founding of New Bern, North Carolina.<br />

The town was founded in 1710 by<br />

MvG’s own Swiss ancestor Christoph<br />

von Graffenried, who had traveled to<br />

the Americas in 1710 and established<br />

what became the sister city to Bern,<br />

Switzerland.<br />

After MvG’s first exhibition, New<br />

Bern’s local newspaper, the Sun<br />

Journal, ran the front page headline,<br />

“Swiss Photos of City Nixed.” The<br />

article by Sue Book reported “Many<br />

of those on the 300th Anniversary<br />

Celebration Committee and the Swiss<br />

Bear Development Corporation board<br />

thought Michael von Graffenried’s images<br />

showed New Bern in an unflattering,<br />

even racist, light.” The newspaper also<br />

reported that neither sponsoring agency<br />

would help to publish the photographs.<br />

That response did not deter MvG from<br />

spending multiple years on his project.<br />

He returned to New Bern after the killing<br />

of George Floyd to photograph the<br />

underserved Black community. In the<br />

book, he combines his original pictures<br />

with his more recent work. He described<br />

his creative process to Swiss Television in<br />

2007, “. . . First, I want to understand if<br />

I’ve understood something. I try to put it<br />

in a frame that explains daily life. I try to<br />

condense a story within one picture. I am<br />

convinced a picture tells more about the<br />

person who is looking at it than about the<br />

one who took it.”<br />

But the most successful pictures are not<br />

about the photographer or the viewer.<br />

Great pictures are about what is inside<br />

the picture frame. MvG admits that he is<br />

not a creator of iconic images. For him,<br />

each photograph must be the story. There<br />

are no photo captions or text, other than<br />

his 124 word introduction. He intends his<br />

panoramic views to chronicle both the<br />

subject and the background details of a<br />

complex reality. The reader is invited to<br />

take cues from the book’s 120 images.<br />

Many of his amazing compositions reveal<br />

uncomfortable situations that are daily life<br />

in New Bern. MvG is a late witness to the<br />

plague of racism in America. There is the<br />

hope that this testament will contribute to<br />

the end of the racism common throughout<br />

the United States.<br />

—Frank Ward<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong>/ 31

Contributors<br />

Sofia Aldinio is an Argentine-American<br />

documentary photographer and storyteller<br />

based between Joshua Tree, California and<br />

Baja California, Mexico. As an immigrant<br />

and Latina, Sofia’s work is guided by themes<br />

like climate change, preserving natural and<br />

cultural heritage, and immigration, amplifying<br />

the stories of immigrants and refugees in the<br />

Northeast of the United States.<br />

Barbara Ayotte is the editor of <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine<br />

and the Communications Director of the<br />

Social Documentary Network. She has served<br />

as a senior strategic communications strategist,<br />

writer and activist for leading global health,<br />

human rights and media nonprofit organizations,<br />

including the Nobel Peace Prize- winning<br />

Physicians for Human Rights and International<br />

Campaign to Ban Landmines.<br />

Kirsten Rebekah Bethmann, aka Kirsten<br />

Lewis, is a Colorado-based international<br />

photographer, educator and public speaker.<br />

She has traveled to over 40 countries to work<br />

with organizations and individuals creating<br />

documentary-based pictures to aid in fundraising,<br />

advertising, awareness and personal family<br />

archive builds, and is the primary force in<br />

the genre of documentary family photography.<br />

Donald Black Jr. is a Cleveland artist who<br />

works with video, installation, and photography.<br />

He is an alumnus of Cleveland School of<br />

the Arts and attended Ohio University, where<br />

he studied commercial photography. Black<br />

received first place in SDN's From Tulsa to<br />

Minneapolis Call for Entries and third place in<br />

Nikon's international photo competition. His<br />

work explores family relationships, racism,<br />

environment, and identity.<br />

Beginning as a freelancer for the Washington<br />

Post, Brian Branch-Price became an intern<br />

and staffer at various publications. As a content<br />

provider, Brian contracts with Zuma Press<br />

and also focuses on portraiture, reportage<br />

and fine art photography. He had several art<br />

exhibits at the Plainfield Public Library on his<br />

legendary Black gospel artists and veterans.<br />

Sheila Pree Bright is an acclaimed international<br />

photographic artist who portrays<br />

large-scale works that combine a wide-ranging<br />

knowledge of contemporary culture. Known<br />

for her series, #1960Now, Young Americans,<br />

Plastic Bodies, and Suburbia, Bright has<br />

received several nominations and awards.<br />

Her work is included in numerous private and<br />

public collections.<br />

Born in Harlem, New York, Sean Josahi<br />

Brown draws inspiration from the common<br />

human experience to capture raw emotion and<br />

share compelling stories that raise awareness<br />

of social issues.<br />

32 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2021</strong><br />

Caterina Clerici is an Italian journalist and<br />

producer based in New York. She graduated<br />

from Columbia University’s Journalism School<br />

and is a grantee of the European Journalism<br />

Centre for her work in Haiti, Ghana and<br />

Rwanda. She worked as a photo editor and<br />

VR producer at TIME, and as an executive<br />

producer at Blink.la.<br />

Daniela Cohen is a non-fiction writer of South<br />

African origin currently based in Vancouver,<br />

Canada. Her work has been published in New<br />

Canadian Media, Canadian Immigrant, The<br />

Source Newspaper, and is upcoming in Living<br />

Hyphen. Daniela’s work focuses on themes of<br />

displacement and belonging, justice, equity,<br />

diversity and inclusion.<br />

Lisa DuBois is an ethnographic photojournalist<br />

and curator with insatiable curiosity, who<br />

raises public cultural awareness through work<br />

focusing on subcultures within mainstream<br />

society. She has exhibited her work internationally<br />

and domestically, contributed to major<br />

news publications and stock agencies, and<br />

had her work for X Gallery recognized by the<br />

Guardian and New York Times.<br />

A Brooklyn-born photographer of a Jamaican<br />

mother and Saint Lucian father, Imari<br />

DuSauzay’s images range from portraits of<br />

people on the street to those of interesting and<br />

notable people. With a Masters degree in<br />

Media Arts from Long Island University, Imari<br />

has worked as an art educator and taught in<br />

programs for children in urban communities.<br />

Iyana Esters combines art with her expertise<br />

in public health, using photography as a lens<br />

to document the human impact of environmental<br />

racism, practices, rituals, and sexualities<br />

related to Black life. An emerging photographer,<br />

Iyana works primarily in long-form<br />

photography and documentary.<br />

Marissa Fiorucci is a freelance photographer<br />

in Boston, MA. She is former studio<br />

manager for photographer Mark Ostow and<br />

worked on projects including portraits of the<br />

Obama Cabinet for Politico. She specializes<br />

in corporate portraits and events, but remains<br />

passionate about documentary.<br />

Prof. Collette Fournier has been photographing<br />

for forty years. She is a member of<br />

Kamoinge, an African-American photography<br />

collective. As an award winning photographer,<br />

her specialties are portraiture, documentary<br />

and nature photography. Fournier is<br />

writing a personal narrative on her journey<br />

into photography and lectures on her production<br />

"Retrospective: Spirit of A People."<br />

After taking a college course in photography,<br />

Jonathan French began to teach himself.<br />

While living in Washington, D.C., he captured<br />

many historic events. Afterwards, he did international<br />

travel and events, as well as many<br />

live concerts. He has taught and has exhibited<br />

nationally and internationally. He currently<br />

lives in Panama.<br />

Cheryle Galloway is a Zimbabwean-born<br />

photographer based in Maryland. Pre-Covid,<br />

Cheryle’s work focused on nature, street and<br />

portraiture. Since February 2020, she has<br />

focused primarily on telling more personal stories,<br />

exploring issues of identity, gender and<br />

race. Her project “Out of Many?” asks the<br />

question, how does America heal to become<br />

one nation?<br />

Terrell Halsey is an artist based in<br />

Philadelphia, PA. He seeks to create visual<br />

poems of humanity while diving further into<br />

his understanding of the world. After receiving<br />

his Temple University BFA, he has exhibited<br />

nationally and also been featured in publications.<br />

His current project focuses on the<br />

contemporary Black experience.<br />

Titus Brooks Heagins is a documentary photographer<br />

and educator adept at capturing the<br />

full emotional and cultural spectrum of diverse<br />

communities. Based in Durham, NC, he has traveled<br />

extensively to produce a diverse body of<br />

work exhibited in many private and public collections,<br />

and taught photography and art history<br />

courses at numerous colleges and universities.<br />