ZEKE Magazine: Spring 2023.2

Feature articles on Ecuador by Nicola Ókin Frioli; Ethiopia by Cinzia Canneria, and Ukraine by Svet Jacqueline. Contents: Piatsaw:A Document on the Resistance of the Native Peoples of Ecuadorian Amazon Against Extractivism Photographs by Nicola Ókin Frioli Winner of 2023 ZEKE Award for systemic change Women's Bodies as Battlefield Photographs by Cinzia Canneri Winner of 2023 ZEKE Award for documentary photography Too Young to Fight, Ukraine Photographs by Svet Jacqueline Picturing Atrocity: Ukraine, Photojournalism, and the Question of Evidence by Lauren Walsh Interview with Chester Higgins by Daniela Cohen

Feature articles on Ecuador by Nicola Ókin Frioli; Ethiopia by Cinzia Canneria, and Ukraine by Svet Jacqueline.

Contents:

Piatsaw:A Document on the Resistance of the Native Peoples of Ecuadorian Amazon Against Extractivism

Photographs by Nicola Ókin Frioli

Winner of 2023 ZEKE Award for systemic change

Women's Bodies as Battlefield

Photographs by Cinzia Canneri

Winner of 2023 ZEKE Award for documentary photography

Too Young to Fight, Ukraine

Photographs by Svet Jacqueline

Picturing Atrocity: Ukraine, Photojournalism, and the Question of Evidence

by Lauren Walsh

Interview with Chester Higgins

by Daniela Cohen

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2023 VOL.9/NO.1 $15 US

ZEKESPRING

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY

Published by Social Documentary Network

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 1

Published by Social Documentary Network

SPRING 2023 VOL.9/ NO.1

$15 US

Photo by Nicola Ókin Frioli from Piatsaw

Photo by Cinzia Canneri from Women's Bodies

as Battlefield

Photo by Svet Jacqueline from Too Young to Fight

2 | PIATSAW

A Document on the Resistance of the Native Peoples of Ecuadorian Amazon

Against Extractivism

Photographs by Nicola Ókin Frioli

WINNER OF 2023 ZEKE AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE

14 | WOMEN'S BODIES AS BATTLEFIELD

Photographs by Cinzia Canneri

WINNER OF 2023 ZEKE AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

38 | TOO YOUNG TO FIGHT

Photographs by Svet Jacqueline

48 | PICTURING ATROCITY

Ukraine, Photojournalism, and the Question of Evidence

by Lauren Walsh

26 |

56 |

2023 ZEKE Award Honorable Mention Winners

Interview with Chester Higgins

by Daniela Cohen

58 | Book Reviews

62 | Contributors

65 | Cover photographer

2023 VOL.9/NO.1 $15 US

ZEKESPRING

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY

Photo by Antonio Denti from The Longest Way

Home

Photo by Michael Snyder from The Queens of

Queen City

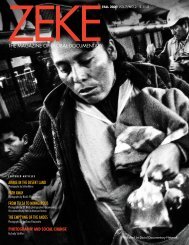

On the Cover

Photograph by Cinzia Canneri

A Tigrinya woman is showing a

religious pendant belonging to her

husband, who went missing during

the conflict in Tigray. She has had no

news from him since. Today she lives

in poverty, supported only by the aid

provided within the camp. Um Rakuba

Refugee Camp, Gedaref, Sudan. June

15, 2021.

ZEKE

THE

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

MAGAZINE OF

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY

Published by Social Documentary Network

Dear ZEKE Readers:

It is always so great to present the winners of the ZEKE Award. Coincidentally

both winners this year are from Italy. Nicola Ókin Frioli is the recipient of the

ZEKE Award for Systemic Change for his project on Indigenous revolt against

extractive industries in Ecuador. And Cinzia Canneri is the recipient of the

ZEKE Award for Documentary Photography for her project on violence against

women, and particularly Tigrayan and Eritrean women fleeing war on both

sides of the border. Congratulations to both! There are also six honorable

mentions who you will find starting on page 26.

As Russia’s destruction of Ukraine continues into its second year, so does

the outpouring of images documenting this horrific war against civilians,

infrastructure, and combatants. In this issue of ZEKE, we are presenting a portfolio

by U.S. photographer Svet Jacqueline, Too Young to Fight, that shines light on the

youngest victims of this senseless war. And to put these photographs in context,

Lauren Walsh, professor at New York University and author of Conversations on

Conflict Photography, has an article Picturing Atrocity: Ukraine, Photojournalism,

and the Question of Evidence that looks at how this outpouring of images by

photojournalists can also be used as evidence of war crimes.

We are also thrilled to be able to present an interview in this issue with Chester

Higgins, a New York Times photographer for more than 40 years and leading

voice in the community of Black photojournalists working to bring a diverse

perspective to our media landscape.

This is our seventeenth issue of ZEKE! With each issue our overriding objective

is to present outstanding documentary photography that we hope educates

and sensitizes our readers to important issues in our world today by using the

language of visual imagery. So much of our intellectual understanding of the

world today is driven by language, which is a much more recent development

in human evolution. Our sight and sensitivity to clues from the visual landscape

have been with us much longer, and we believe these clues give us an

important perspective on our world that we cannot gain by words alone.

Fundamentally this is why we publish ZEKE and is also the foundation behind

the Social Documentary Network.

I hope you as readers agree on the importance of this visual landscape and

will continue to value ZEKE magazine as a vital source of information about our

fragile and forever changing planet and the people, animals and other forms of

life that cohabitate this precious speck in the universe.

Glenn Ruga

Executive Editor

2023 ZEKE Award Jurors

Barbara Ayotte: SDN

Communications Director and

Senior Director of Strategic

Communications at GBH

Greig Cranna: Director,

Bridge Gallery, Cambridge,

Massachusetts

Donny Bajohr: Associate Photo

Editor, Smithsonian magazine

Lisa DuBois: Independent photographer

and curator, SDN Board

member

Anne Farrar: Assistant Managing

Editor, National Geographic

magazine

Avi Gupta: Director of

Photography, U.S. News and

World Report

John Heffernan: President,

Foundation for Systemic Change

Michael Itkoff: Cofounder,

Daylight Books

Danny R. Peralta: Executive

Director, En Foco

Eli Reed: Member of Magnum

Photos and a member of

Magnum’s Board of Directors

Barbara Ayotte

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 1

ZEKE AWARD FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE

FIRST-PLACE WINNER

Piatsaw

Photos by Nicola Ókin Frioli

Ecuador

Piatsaw was the first man, and God, of

the Sapara mythology who prophesied

the end of the culture of his people.

This documentary tells the story of the

resistance that the Indigenous people

of the Ecuadorian Amazon have

waged against extractive companies

that threaten their territories through

continuous concessions and contamination

caused by Texaco during its

presence in the country. In 1964, Texaco

(now Chevron), arrived in Ecuador with a

concession of 1.5 million hectares in the

provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana. At

that time, they were extracting oil from

450,000 hectares. The oil giant admitted

in court to having dumped 19 billion

gallons of crude

oil and harmful

A Document on the Resistance of the Native

chemicals directly

into unlined

rivers and pools

in a particularly biodiverse region of the

Ecuadorian rainforest over decades. The

health and future of the inhabitants were

affected by contaminants present in the

soil and groundwater, quantities exceeding

permissible levels in Ecuador.

Following the events that indelibly

marked the future of many families,

the Native peoples of the Ecuadorian

Amazon applied different defense methodologies

against mining, oil companies,

and the government. Armed confrontations,

national strikes and their presence

in the courts were the strategies that the

Indigenous nationalities used to stop the

loss and destruction of their territories as

they consider their environment part of

their body and plants and animals are the

other members of their society.

2 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Peoples of Ecuadorian Amazon Against Extractivism

Indigenous women in protest,

confronting police in Quito.

December 2016.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 3

A Kichwa woman looks into the window

of a light aircraft that has landed

in the community of Morete in Sapara

territory. Morete, like other communities

within this territory, can only be reached

by air and the arrival of a plane is a

special event.

The Sapara are the ancestral owners

of the largest Indigenous territory in the

Ecuadorian jungle. It is estimated that

only 573 Sapara Indians now live in a

territory of more than 3,100 hectares of

primary rainforest.

Today, the Kichwa communities and

some settlers also live in this territory

and consider oil extraction as a solution

to their economic instability without

considering the environmental impact,

destruction and contamination that it

would cause in their surroundings.

4 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 5

Antonio Mayancha, coordinator of

Sisa Ñampi (Border of Life), planting

trees under the rain. In 20 to 40 years

these trees will exceed the size of the

rest, and when flowering, they will

delimit the perimeter of Sarayaku’s

sacred territory, Pastaza Province.

The struggle for the conservation of

the Kichwa territory began with the

arrival of oil companies in Ecuador.

Since then, the community has

remained united in resistance for the

defense of the forest and the preservation

of their biocultural heritage.

Sarayaku is called, according to

an ancient prophecy of the shaman

ancestors, “The people of the Noon”

for being a pillar of territorial, cultural

and spiritual defense, a lighthouse as

strong as the midday sun, and the last

Native people to fall in the face of the

extractivist threat.

6 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 7

Singangoe Community, Sucumbio

Province, Ecuador.

Osvaldo, Indigenous from Sinangoe

community, with his viewfinder during a

day of training to use drones and GPS

localizers.

On October 22, 2018, the Kofan

people of Sinangoe from the

Ecuadorian Amazon won a landmark

legal battle to protect the headwaters

of the Aguarico River, one of Ecuador’s

largest and most important rivers, and

nullify 52 mining concessions that had

been granted by the government in

violation of the Kofan’s right to consent,

freeing up more than 32,000 hectares

of primary rainforest from the devastating

environmental and cultural impact

of gold mining.

8 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Gerardo Gualinga, Chief of the

Wío Indigenous security group, of

the Kichwa Indigenous people of

Sarayaku.

Wío is the name for a small ant that

lives in the jungle. Despite its size,

its bite produces painful itching,

fever and blindness. For this reason

it became the name of the security

and monitoring group of Sarayaku.

Strategically prepared, they monitor

and defend the territory when

necessary, make operative rescues,

take care of women, manage the

entry of foreigners and strangers

to the territory, and the security of

the Chairman of the Tajsajaruta

(Government of the Kichwa Nation).

Gerardo poses for the photo with

a firearm, the last option for an

armed confrontation in case there

is a violent action by the military or

members of an oil company.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 9

10 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Don Luis has not walked for a year.

He suffers from a disease unknown

to him and his relatives. There has

been no official medical diagnosis.

Local doctors hypothesize that it is

colon cancer and muscular dystrophy.

For men, colon cancer is one of the

most common diseases in the region.

Sacha District, Orellana Province.

A recent study by Unión de Afectados

por Texaco (UDAPT) confirms that

the percentage of cancer patients in

Ecuador is much higher in provinces

with extractive activities.

ZEKE ZEKE SPRING FALL 2021/ 2023/ 11

12 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

A group of young Kichwas people in

Cantón Santa Clara on watch during

a meeting organized in order to stop

the construction of the hydroelectric

plant above the Rio Piatúa. The community

was not consulted before the

start of the process.

The company Genefran started

preliminary works that were stopped

by Indigenous pressure in defense of

the river, their primary source of water.

The Indigenous declaration was that

they would burn one machine each

day until the company removed it

permanently from the site.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 13

ZEKE AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY

FIRST-PLACE WINNER

WOMEN’S

BODIES AS

BATTLEFIELD

Photos by Cinzia

Canneri

Ethiopia

The targeting of women’s bodies

in times of war, but also in times

of peace, has come to light as a

systematic strategy that has been

used by different actors in many

different contexts worldwide. This

project has analyzed the condition of

Eritrean and Tigrinya women who moved

across the borders of three countries

geopolitically linked to one another:

Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan. From 2017

to 2019, the work has documented

Eritrean women fleeing from one of the

most repressive regimes in the world

and seeking refuge in Ethiopia. From

November 2020, following the invasion

of Tigray (Ethiopia) by the Ethiopian

Federal Army supported by the Eritrean

military forces and Amhara militia, the

project’s focus has broadened to include

also the Tigrinya women, who joined

Eritrean women in their escape from

Ethiopia to Sudan. In Tigray, the Eritrean

army used sexual violence as a weapon

of war against both Eritrean and Tigrinya

women: to punish those fleeing their

country in the former case, and as an act

of extermination in the latter. The bodies

of women became a battlefield on which

there are no sides.

14 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Yohanna, 22, lies next to her mother

after having a kidney removed

following being shot in her abdomen

at the border in Shambuko, Eritrea.

The Eritrean police wanted to send

her mother home after two years of

detention due to her unstable health

condition. Yohanna’s mother had been

imprisoned for not providing information

about her husband’s whereabouts,

even if she had lost all contacts with

him, once he had fled to Jerusalem

in 2015. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

October 31, 2017.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 15

16 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

Regat, 37, grew up in Eritrea and

escaped to Ethiopia in 2010. She says

“I left Eritrea partly to help my family

with their deep economic troubles, but I

can't see a future ahead.” She currently

works at a café because she needs

money to try to reach Sudan, but she

only earns 600 birr – 12 dollars – per

month. Axum, Ethiopia. April 4, 2019.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 17

18 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Yemane, 23, shows a scar caused by

soldiers during a shooting in Tigray.

Yemane escaped from Eritrea and

lived in the Mai Aini camp when the

war broke out. She was there with her

husband, two children, and her sister.

During the escape she was raped in

front of her children and her husband

was captured and taken away.

At the border, while soldiers were

shooting at her husband, her sister

was wounded and Yemane managed

to run with her children. She still

doesn’t know whether her sister is

alive or dead. Yemane suffers from

anxiety disorders linked to posttraumatic

stress, and she feels

responsible for not aiding her sister.

The UNHCR declared that 24,000

Eritrean refugees in the Mai Aini and

Adi Harush camps, located in the Mai

Tsebri area in Tigray, have lived in a

state of constant terror and could not

access humanitarian aid of any kind.

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. November

30, 2022.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 19

A refugee Eritrean woman stands

under a tree just outside the Hitsats

Refugee Camp, Ethiopia, March

31, 2019. The Hitsats camp hosted

almost 23,000 Eritrean refugees and

its population has more than doubled

since the border opened following

the peace deal between Eritrea and

Ethiopia in 2018. It is one of the four

refugee camps in Tigray for Eritreans,

who make up the third largest refugee

population in Ethiopia with 173,879

officially registered. The war in Tigray

started on November 4, 2020 and

has caused violence against Eritrean

refugees gathered mainly in the camps

of Hitsats, Adi Harush, Mai Aini and

Shimelba, in north Ethiopia. Different

sources have reported that forced

repatriations have been practiced from

these camps and the estimated number

of deportations is 6,000.

20 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 21

Rita, a refugee from Eritrea, shows

some objects she treasures, once

belonging to her daughter Elena

who died when she was seven

years old while she was crossing the

border between Eritrea and Ethiopia

in 2016. Elena had a congenital

liver disease and her health condition

did not allow her to survive the

journey. Elena was buried along

the migration route in a place that

doesn’t have any connection with

her family. Rita says she would like

to live where her daughter was

buried: “Having moved away from

my daughter's body means having

lost her a second time.”

22 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 23

An Eritrean girl walking along the

railway that connects Eritrea with

Ethiopia. The majority of children

in Eritrea grow up without the

protection of parents, who have

emigrated or are serving in the

military indefinitely in unknown

locations. This causes children to

develop a strong desire to escape

to a new life and to leave their

country at a young age.

As a result of the peace agreement

between Eritrea and Ethiopia

signed in September 2018, the

average daily arrivals to Europe

in the three months following the

reopening of borders revealed that

many children have actually run

away without their family knowing

it, often in the attempt to reach their

parents already abroad.

Foundation Human Rights for

Eritreans (FHRE) has denounced the

international community for providing

aid to Eritrea, which even after

the peace agreement with Ethiopia

still maintains a dictatorial regime

considered the worst after North

Korea. This causes Eritrean people,

including many unaccompanied

minors, to leave.

Asmara-Massawa road, Eritrea.

March 23, 2019.

24 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 25

ZEKE AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Jacinta Legei, 44, advances the

women’s traditional praying

group in the dry Dol Dol landscape.

The prayer ceremony is

held for rain amid the ongoing

drought. It usually lasts for four

days. The people in this area

have not had good rains for

the past three to four years. The

landscape is dry and it is full

of invasive cacti species. This

combination leads to increased

deaths among their livestock.

Consequently, poverty is widespread.

Dol Dol, Laikipia county,

Kenya (February 2022).

26 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Rasha Al Jundi

Red Soil: Colonial Legacy in Maasai Land | Kenya

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

This is a story that spans

generations.

About the man in a redshuka,

and the woman with a beaded

necklace.

Indigenous peoples, once mighty,

controlling territories that

spanned borders.

A tribe, rich with traditions,

culture, knowledge and history.

Uprooted, fragmented and fenced

off from their ancestral lands.

A historical injustice with

contemporary consequences.

The Maasai, of Laikipia county,

live in a state of negative peace.

Colonizers pushed them away

from the red soil of the Rift

Valley, into confined reserves.

Present day governance trades

with their lands and grievances.

Fortress conservation, drought and

bouts of conflict surround them.

Prejudice mutes their voices.

Peace, without justice, is present.

The threat to their way of life is

real.

Yet, they are here, holding us

witness to their story.

One of perseverance, adaptability

and courage.

That of the man in a redshuka

and the woman with a beaded

necklace.

Above: A warrior from the

Samburu tribe, armed with an

AK-47, watches his herd of cows

cross the river separating Laikipia

from Isiolo county. Guns are

increasingly becoming the weapon

of choice among pastoral tribes in

Kenya for the purpose of protection.

They can be easily bought

in the black market for the price

of five to six cows (approximately

USD 2,000-5,000). Laikipia

county, Kenya (February 2022).

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 27

ZEKE Award for Systemic Change

HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Antonio Denti

The Longest Way Home | Vatican City and Canada

28 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Indigenous Canadians at the Vatican

to meet Pope Francis. Vatican City.

In April 2022, it was quite

something to see Indigenous

Canadians, proud in their

costumes, under Bernini's

colonnade at the Vatican waiting

to meet the Pope. When the

impressive monument was being

built in 1600, their colonial

catastrophe was starting. It was

also quite something only a few

months later to see the aging

Pope, in deep pain due to a troubled

knee, travelling to Canada's

desolate plains, to the Arctic

frontier, to the sacred lakes, to

the ancestral lands to say: “I am

sorry.” Systemic change may have

started then as the beginning of

a difficult path of reconciliation in

the scarred lands.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 29

ZEKE AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Nyani Quarmyne

Connecting the Caucasus | Georgia

Lasha Tunauri and his packhorses

wait while Konstantin Stalinsky,

Giorgi Kirvalidze, and Amirani

Giorganashvili complete

construction of a tower on Kheki,

a mountain peak in Tusheti in

the Greater Caucasus Mountains

in the Republic of Georgia.

The tower was part of a solarpowered

wireless network to bring

broadband Internet access to

Tusheti. The project was the result

of a partnership between several

local and international Internet

and development organizations

and aims to provide a way for the

people who live in Tusheti to build

opportunities while preserving

their local heritage, traditions, and

ways of life.

30 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Tusheti, draped across the

Caucasus Mountains in

Georgia, is all but cut off

for most of the year—the

only road in, through the treacherous

Abano Pass, is impassable

in winter. An occasional Border

Police helicopter becomes the only

link with the outside world. The

region is the ancestral home of

the Tush, traditionally nomadic

shepherds. Today, due largely to

Soviet-era resettlement policies,

most live in the lowlands; few

brave winter in the mountains.

But when the Abano Pass

opens in spring, Tush flood into

the highlands, shepherds among

them making a ten-day trek with

their flocks. There is a sense that

for most Tush, the mountains

are their real home. Tourism has

become the economic mainstay:

seasonal guesthouses cater to

summer hikers. But they are constrained

by the very remoteness

that is their main attraction.

Aiming to boost tourism by

getting businesses online, a group

of volunteers set out to bring the

Internet to the mountains. They

hope that increased economic

opportunity will slow the drift

of young people to cities, and

make it possible for the Tush to

once again live year-round in the

mountains.

Top: A shepherd driving a flock of

sheep into the Abano Pass along

the road to Tusheti

Bottom: Tamari Khucishvili playing

with her daughter, Sophia, at their

home in Omalo, the central village

in the remote mountainous region

of Tusheti.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 31

ZEKE AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Jean Ross

Displaced | Georgia

This family is one of the few left in the once-grand Metalurgi

Sanatorium in Tskaltubo. During the past two years, the

Georgian government has stepped up efforts to relocate

residents to better housing.

32 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Top right: Murtazi lives in Kartli, a former cardiology clinic

near the shores of the Tbilisi Sea, on the outskirts of the nation’s

capital. He has a daughter and new grandchild in the U.S.

Bottom right: Gulo wore this coat, representing a large share of

the family’s wealth, when she was forced to flee Abkhazia. She

and her husband, Oscar, are now among the last remaining

residents of the former Aia Sanatorium in Tskaltubo.

.

Long before the invasion of

Ukraine, Russian military

forces intervened in

multiple wars in Georgia;

first in Abkhazia in the early

1990s and later in South Ossetia.

Roughly a quarter of a million

people, mostly ethnic Georgians,

were displaced during the

conflicts. While many remained in

the areas bordering the conflict

zones, others relocated to Tbilisi

and other cities, often living

in large congregate housing

complexes. Continued hostility,

exacerbated by ongoing Russian

presence, has dimmed displaced

families’ dreams of returning

home. These images, and the

stories that go with them, document

their multi-decade struggle

for social and economic integration.

They also explore broader

questions regarding the treatment

of civilians displaced by armed

conflict broadly and the specific

humanitarian toll of Russia’s wars

against its neighbors.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 33

ZEKE AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Mustafa Bilge Satkın

Drowned History | Turkey

Aye is the youngest member of a family of eight children, and

she has to work at harvest time like all family members. In the

past, these people were able to do irrigated farming on their

land near the Tigris River. Now the farmers are forbidden to

use the water in the dam. Drought caused a decrease in the

amount of grain in the region.

34 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

The construction of the

Ilısu Dam in Turkey had

devastating impacts on

the local community and

environment in the Dicle Valley,

a 100 km-long area along the

Tigris River. The project resulted in

the displacement of over 10,000

people, most of whom are Kurdish

and Arabic, and the submergence

of 198 villages, including the

ancient city of Hasankeyf, one of

the world’s oldest continuously

inhabited settlements.

Despite this, the dam was

constructed as part of the state’s

water policies, with little regard

for the consequences it would

have on the local community and

environment. The inhabitants of

villages were forced to abandon

their ancestral homes, sell their

livestock, and move to a hastily

built new town. The process of

moving was emotionally distressing,

as people had to exhume the

graves of their loved ones and

carry their remains to the new

town so future generations could

visit their ancestors.

Top: A suburb near the center of

Sırnak. The Kurdish group, which

came from different places, is

trying to keep their old traditions

alive. They have fun in solidarity

with their local clothes and traditional

games.

Bottom: Elif is a family member

engaged in animal husbandry.

Due to the overheated water that

has become stagnant, his family

is considering giving up livestock

and emigrating to the big city.

Many families cannot get enough

efficiency from agriculture and animal

husbandry due to the negative

conditions created by the dam.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 35

ZEKE AWARD HONORABLE MENTION WINNER

Above: French Silk poses in a practice bow hunting range on an unoccupied floor

of a commercial building near Cumberland, Maryland. “This place is as country as

it gets. Pretty much everyone that I knew growing up went hunting. It never seemed

like the kind of place where different sexual identities and things like drag could

ever exist. It still blows my mind that this is happening here. But I am proud that it is.

I am proud to be a part of this.”

This project is funded in part by the Pulitzer Center

and will be published in the summer issue of the

Virginia Quarterly Review.

36 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Michael Snyder

The Queens of Queen City | Maryland, United States

America is, by admission

of most of its political

leaders, a nation shaped

by deeply held religious

beliefs and cultural values. And

perhaps nowhere is this truer than

in Appalachia, a mountainous swath

of America’s eastern midsection,

known for its Rust Belt work ethic

and its Bible Belt conservatism.

Here, Cumberland, Maryland was

once the “Queen City,” a hub of

industry and culture. But the story

of Cumberland has paralleled that

of many once-great cities throughout

the Appalachian region: the gradual

departure of industry and, with it, a

slow descent into economic stagnation

and cultural decline.

But even here, flowers are

growing in the cracked pavement:

a queer community has banded

together, created a thriving drag

scene, and—against all odds—built

the largest Pride movement in the

region. The “Queens of Queen City”

is a documentary project exploring

the courage, risks, and repercussions

of openly expressing LGBTQ identities

in rural, conservative America.

The project charts the course of this

queer community over five years as

they struggle with loss, bigotry, and

acts of arson, to build an inclusive,

vibrant community.

Top: Claire, Mary Jane, and Aradia

cool off in a local swimming hole

outside of Cumberland, MD. “I

grew up outside.” Says Aradia. “I

am just as country as anybody is.”

Bottom: Iva Fetish blow dries their

nails during a drag pageant at

the Embassy Theatre. “I’m a dirty

Queen.” She says. “I’m a dirty

girl. I’m not like one of these pretty

things here.” She says, pointing

toward the pictures on the wall.

“It’s OK though honey, I love myself

anyway. I embrace my bad side.”

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 37

Young To Fight” focuses on the

“Too

lives of Ukrainian children since

Russia invaded Ukraine on February

24, 2022. The stories are heartbreaking.

I first arrived a week after the

invasion started. I was thrown into the worst

parts of this conflict. I spent my mornings

at funerals, my afternoons watching fathers

say a tearful goodbye to their families

boarding trains, and my nights in bunkers

listening to the echoes of artillery fire.

I have now spent over five months

documenting this cruel and unnecessary

attack on Ukraine—and democracy. The

landscape of this war changes daily. As

of September 2022, over 1,000 children

had been killed in Ukraine—some have

been tortured and their bodies burned.

Others have sustained injuries from shelling

and are spending birthdays and holidays

in hospitals getting fitted for prosthetics.

Thousands are accepting a new life of living

underground dreaming of a day when they

can go back to school—or just to dance

class. The rest—those who account for the

over five million refugees who were forced

to flee since the war started—are doing

their best to assimilate in places that will

never feel like home.

The beautiful thing about children is the

joy they find in the most unlikely of circumstances.

They embody the Ukrainian spirit

in its purest form. They run, play, and laugh

in the face of the evil that has become their

reality.

As they grow older, some of them will

be drafted into the war as young adults.

Some will help raise the siblings that their

parents died to protect and some will never

return to their childhood homes or cities

again. I will continue to photograph their

stories—the ones that capture the innocence

that war destroys. As the world starts to turn

away from the headlines from the war, I ask

that we recognize that the shadows of this

period in history will follow us, reflected

through the eyes and stories of Ukrainian

children as they find a more permanent

identity.

Too Young

to Fight

Photos by

Ukraine

Svet Jacqueline

A family takes a train toward Lviv as

violence increases in Eastern Ukraine

on April 25, 2022. The displacement

of over four million refugees has

been recorded since the start of the

Russian invasion.

38 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 39

Police guarding Liberty Square

in Kherson are passed by a

young girl running. Kherson was

officially liberated after eight

months of Russian occupation on

November 11, 2022.

40 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 41

42 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Petro, 49, and his daughter Emily,

6, read a book together in his

hospital bed in Lviv on November

16, 2022. Two months into his

service, outside of Kherson, his

vehicle hit an anti-tank mine causing

him to lose both his legs and

two fingers on his left hand.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 43

44 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Two young boys emulate Ukrainian

soldiers at a makeshift checkpoint on

May 25, 2022. They have become a

symbol of playful hopefulness in their

neighborhood in Chuhuiv in eastern

Ukraine.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 45

A young girl and her brother

look out the train car window on

March 18, 2022, as they head

west to Poland not sure when they

will return home.

46 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 47

Picturing

Atrocity

By Lauren Walsh

Ukraine,

Photojournalism,

and the Question

of Evidence

48 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Iryna and Viktor Dudnyk weep over

the body of their son Dmytro, 38,

killed in a Russian rocket attack in

Kherson, Ukraine, December 10,

2022. © David Guttenfelder for

New York Times.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 49

Picturing Atrocity

A

little

over three

years ago, I published

my book Conversations

on Conflict Photography.

It takes a deep dive

into the journalistic

world of photographing war and

crisis, exploring topics such as

physical risks and emotional tolls

that photographers face, questions

around censorship of graphic

imagery, public fatigue in response

to difficult images, and the impact

of repeatedly negative portrayals

of peoples and places. The whole

book was born from an episode that

happened in one of my classes at

NYU, where I teach. In response to a

photograph of a severely emaciated

man, taken during a devastating

famine, a student said, “I don’t see

why I should care about that person.

There’s nothing I can do anyway. So

why should I be made to feel bad?”

He went on to say that he had plans

that night and didn’t want his mood

spoiled by the depressing photo.

It was a stunning moment for me

as an educator, normally privileged

to spend time with students who do

want to engage with the subject

matter and who do endeavor to

think about ways to raise public

awareness or minimize others’

suffering. It was a moment that

forced me to think deeply about

why images of pain and atrocity are

created, how they are seen, and

when (or if?) they have value. After

all, though my student’s choice of

words may have been insensitive, he

isn’t the only one to feel that way. If

we are being honest, we probably

all have seen a photo that generated

a sense of “but what can I do to

make things better?” Sometimes the

photo is just too much to take in, too

distressing to look at.

So, is there a purpose to making

pictures of the most horrific scenes

imaginable? Do photojournalists

actually record all the brutally

egregious situations they witness? Is

there benefit to that documentation?

These are questions I still think

about – now anew with the war in

Ukraine. Accordingly, this essay

Is there a purpose to making pictures of

the most horrific scenes imaginable?

Markings on the wall inside a torture chamber, where, allegedly, Russians held individuals to extract information.

Survivors claim they were kidnapped, bound, detained, and starved, and the brutality included electric

shock torture and psychological threats. Kherson, Ukraine, November 2022. © Julia Kochetova.

explores these questions through the

contemporary lens of photographing

atrocity—war crimes and other

grievous violations—in one of the

deadliest conflicts in Europe since

World War II.

TOUGH DECISIONS

Photo editors occupy a vital part

of the photojournalism chain. They

make the tough decisions about

which images to disseminate, how to

contextualize them, and why. Violent

images can lead to visceral reactions

in the news-consuming public. Some

may look away (as my student

advocated), but others get upset, if

not angry.

The violence of an image isn’t

necessarily graphic. Photographer

David Guttenfelder caught the

emotional devastation etched on

the faces of an elderly couple, as

they stand over the body of their son

who perished in a Russian rocket

attack in Kherson in December. The

accompanying words in the New

York Times article [Dec 15, 2022]

amplify the impact of the image,

referring to the “unspeakable grief”

that consumes survivors in the wake

of random death as “the world

shrugs and moves on, often oblivious

to the terrible impact on families and

lives.” Guttenfelder’s photo is a visual

attempt to stop us from shrugging,

and to force us to acknowledge

the far away suffering, possibly

asking us to suffer (or at least feel

discomfort) a little bit, too.

That image, though raw with

emotional anguish, is, in many

regards, discreet. The body of

the son is largely hidden, only his

blanket-covered legs in the frame.

For many photo editors, the most

difficult decisions play out around

images of explicit physical violence—

much of which they themselves must

examine. Washington Post photo

editor Chloe Coleman describes

this in an article for Nieman Reports

[Apr 15, 2022], “As the Russians

have retreated from parts of Ukraine,

journalists’ access to the sites of

apparent atrocities have resulted in a

flow of especially gruesome scenes,

many of which I must review and

consider from my desk: body bags

(closed and opened); murdered

50 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

civilians, burned, their hands bound,

some dismembered.” She then asks:

“What do readers need to see to

understand the reality of war without

our coverage being gratuitous?”

In short, there is a line that photo

editors try not to cross—one that isn’t

overly sensational, one that doesn’t

re-traumatize survivors, one that

doesn’t repulse their readers. Because

a repulsed reader is one who turns

away and doesn’t take in the news.

Coleman explains that news

consumers need to understand that

civilians and soldiers alike are dying.

But, she muses, “Do they need to see

identifiable faces of these people?

Not usually.” Both Coleman and

Heidi Levine, a seasoned combat

photographer who has been

covering Ukraine for the Washington

Post, refer to such images as

“evidence.” In particular, Levine, who

authored a Post article [Apr 8, 2022]

about what she witnessed after

Bucha was liberated from Russian

control, observes, “It was a scene

that I knew had to be documented

for evidence.”

EVIDENCE

But whom is this evidence for? And

what is it evidence of?

At a basic level, it is for the broad

public to see, generally in a way

that isn’t utterly visually repugnant—

so we can grasp the destruction

occurring during this war.

It is also evidence for policy

makers. The international outrage

after Bucha was liberated was no

doubt influenced in large part by

the journalism created in early April

2022, including photos of dead

bodies, mass graves, and tortured

victims—“the visible signs of war

crimes,” as Levine put it.

“I am horrified by the images of

civilians lying dead on the streets,”

stated Michelle Bachelet, then-UN

High Commissioner for Human

Rights. Heads of state condemned

the apparent crimes in Bucha;

the president of the European

Council, as well as other European

leaders, promised greater sanctions

on Moscow. Zelensky called it

genocide. And Biden labeled Putin

a war criminal, as he pledged a

continued supply of weapons to

Ukraine alongside further sanctions

against Russia.

The on-the-ground accounts from

photojournalists like award-winning

Carol Guzy are chilling. In a

Yahoo!News piece [Apr 22, 2022],

the photographer describes Bucha,

saying “It was just horrendous. Its

[sic] apocalyptic.” The images in that

article, like many that were published

when Bucha was liberated, are

difficult to view; some even push the

envelope with the graphic nature of

what is depicted.

By and large, however,

mainstream media handles such

documentation very sensitively,

offering views of death that protect

both the viewer and the dead.

The composition of an image may

render faces obscured or individual

identities imperceptible; piles of

bodies might be pictured from a

distance; and torture may appear as

a detail— a close-up of bound hands

on a deceased victim, for example.

We can think of such imagery as

taking an evidentiary stand against

Russian disinformation. Responding

to allegations of carnage in Bucha, the

Russian Ministry of Defense asserted

that “not a single local resident

suffered from any violent actions”

under Russian occupation.

For some photojournalists, there

is also the hope that their images

may be used to provide evidence of

violations of international humanitarian

law (IHL), a set of rules that govern

conduct in armed conflict and which

seek to mitigate the suffering of

non-combatants. As veteran war

photographer Lynsey Addario said

[Business Insider, Mar 8, 2022] after

witnessing a family killed by a mortar

strike outside the capital city of Kyiv,

“I thought it’s disrespectful to take a

photo, but I have to take a photo. This

is a war crime.”

The International Criminal

Court (ICC), working with special

investigators, is already probing

the possibility that war crimes have

been committed in Ukraine—one

of the few times in history that such

work has been undertaken within just

weeks of the apparent crimes.

Evidence of a war crime, or

of other violations of IHL (such

as genocide), could lead to the

indictment and prosecution of

the perpetrators. In an extensive

analysis of the killings in Bucha,

published on December 22, 2022 in

A hand in a mass grave in Bucha, Ukraine, April 2022. As of June that year, the Head of the National Police

in Ukraine reported that 1,137 people were killed in the greater area of Bucha during the Russian occupation.

© Julia Kochetova.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 51

Picturing Atrocity

the New York Times, the reporters

observe, “Historically, journalists

and investigators relied on a single

photograph or video to expose

wartime atrocities.” Today, the

authors note, there is so much more,

in quantity and detail, in terms of

documentation. So does the still

photo remain as useful a piece of

evidence? And can photojournalists

really produce documentation that

will stand scrutiny in a tribunal?

PHOTOJOURNALISM

AND WAR CRIMES

Janine di Giovanni, a longtime

war correspondent, has helped to

initiate a novel approach to human

rights monitoring and journalism.

She is the Executive Director and

Co-founder of The Reckoning

Project, which, she explains, is a

Ukrainian-led team of experienced

human rights professionals—former

investigative journalists who have

received training in understanding

international humanitarian law and

how to create viable documentation

for IHL cases. “My vision for this

was that frontline witnesses were

absolutely the most important people

in this puzzle of international justice.

But in prior cases, when journalists

got called to the Hague, most of the

time, their evidence didn’t stand up.

It wasn’t transcribed correctly, or they

haven’t got witness statements. I know

because I myself have been called

several times to give evidence.”

This “mobile war crimes unit,”

as di Giovanni describes the team,

focuses on gathering and verifying

evidence and building cases in

order to combat the “plague of

impunity” she sees in the wake

of armed conflict. The Reckoning

Project currently consists of twentythree

researchers, all journalists

by background but none of whom

are photojournalists. This raises

the question of whether wartime

press photographers should receive

training or knowledge around IHL

and tribunals. If photojournalists

were given this background,

could their work be more useful to

investigators and prosecutors?

In some senses, yes. Lawrence

Douglas, a titled professor and prolific

author based at Amherst College and

Can photojournalists really produce

documentation that will stand scrutiny in a

tribunal?

an expert in war crimes and other

mass atrocity prosecutions, explains,

“If you’re taking a picture of a corpse

on the street, we need to know not

only exactly where that street is,

but a sense of the environment. For

example, let’s say there is a trail of

blood. Document it. The corpse has

been moved. That’s relevant. It might

not be relevant as an image to supply

to your newspaper; but it could be

very important for the purposes of

establishing what exactly happened

there.”

Wendy Betts, the Founding

Director of eyeWitness to Atrocities,

concurs: “I wish I could say to the

photojournalist, ‘But what’s behind

you?’ A panorama would be great,

just one 360 so we can see what’s

around.”

For Betts, this gives a fuller picture

and can help the work of investigators.

Her organization, established by

the International Bar Association,

works to collect verified images of

potential war crimes through an

app, facilitating the authentication

process and streamlining some of the

forensic work required for building

IHL cases. She explains that there

are two primary aspects to consider

when evaluating imagery for use as

evidence: its relevance to the case

(how does it matter here?) and its

reliability (is it authentic? Is the “chain

of custody” intact? That involves

tracing the lifespan of the image to

ensure it has not been compromised,

for instance through Photoshop or

other manipulation).

Betts recalls a training session

where a crime scene investigator

asked a journalist, “What would you

photograph?” The response from

the photographer? They would find

what’s most compelling, would be

thinking about framing and angles,

would capture what’s most emotive

for a viewer to induce them to read

and learn more. By contrast, says

Betts, evidence photos are “often

boring. They’re shot at 90 degree

angles and they are looking at things

like license plates and shell casings.

That makes them relevant.”

In this sense, Douglas appreciates

that photojournalists, particularly

those with experience in war

zones, likely recognize that they

are documenting “not just an act of

war, but potentially a criminal act.”

But he adds, “knowing how to do

that in a professional [investigative]

fashion,” will strengthen the value of

the imagery for potentially building

an IHL case. “Once you decide to use

the images for specific evidentiary

purposes to prove the guilt of the

accused, then you’re suddenly in a

very different world than you are in

when you’re using the images in the

national or international press for the

purposes of trying to get people to

take these atrocities seriously.”

PHOTOJOURNALISTS

ON THE GROUND

Evgeniy Maloletka, a Ukrainian

Associated Press (AP) freelancer,

offers the photojournalist’s perspective.

He has a working if not studied

knowledge of what constitute violations

of IHL: “When Russian tanks shoot

apartment blocks. When airstrikes

hit apartment buildings or hospitals. I

52 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

Subscribe to ZEKE today and

receive print edition. Learn more » »

Maloletka’s Instagram post on January 14, 2023.

“Russia attacked civilian neighbourhood. This is a

War Crime.” Screenshot by the author.

didn’t study war crimes; I don’t have

training. I learned it in the field.”

But his images differ from

investigators’. As a photojournalist,

he prioritizes affect. “You concentrate

mostly on emotions, so viewers can

connect.”

Both Douglas and Betts see

tremendous value in photojournalistic

images, even if the photographer isn’t

trained in IHL. “The photos may help

to corroborate witness testimony. They

may help to flesh out the story that

some of the more forensic information

is offering. And really there’s no

one silver bullet piece of evidence in

these types of trials, because they’re

so vast. It is one incredibly large

evidentiary puzzle,” says Betts. She

adds that the traditional means of

getting photos entered into evidence

is to bring the photographer in to

testify to the fact that they took the

image and have not manipulated it.

“This is still the primary and probably

preferred way of most courts.”

In short, mainstream media and

war crimes investigators bring

differing expectations to their

approach to visual documentation.

As Betts observes, evidence photos

may reveal victim’s identities or

even perpetrators in commission

of the crime itself – imagery that is

sometimes sanitized by media outlets.

Maloletka echoes, “You’re

thinking prior about whether you will

show the faces. You don’t want to,

if possible. If you’re photographing

an injured person, you don’t know

if they will live or die, so you try

to hide their identity, for example,

because you don’t want their

relatives to find out this way.”

Betts and Douglas, while mindful

of limitations, emphasize the benefits

of photojournalistic imagery. “You

might see bodies lying on the

street, but not see their faces,” says

Douglas. “Yet often the identity of the

victims isn’t necessarily crucial if you

are aware that they are civilians,” he

adds, referring to the fact that attacks

on civilians is a violation of IHL.

Maloletka explains that he will

document a graphic scene—even

knowing the AP may not use some

photos for being too brutal—for his

own remembrance, to acknowledge,

if only personally, what he witnessed.

Rarely, he may share those images

publicly, via Instagram, with a

graphic content warning, as he did

in October 2022 with photos of

rotting Russian corpses, because,

as he says, “war is ugly and

Russians should see their own dead

soldiers as well.”

Julia Kochetova, another

Ukrainian photojournalist who has

worked for outlets such as Vice,

Guardian and Der Spiegel, echoes

many of these points. She, too, has

never received any training in crime

scene photography, but assuredly

states, “I witnessed the aftermath of

war crimes in Bucha.”

In relating an episode from

Kherson, Kochetova adds another

layer to this discussion: the

photojournalist cannot alter the

scene. “I saw the body of a woman

who had been raped and killed

violently. You could see the bruises

and the signs of the sexual attack. I

spoke with neighbors who confirmed

that Russians did it. They were in

uniform.”

“I knew that I was the only

person there with a camera so I

needed to document. The body

was partially naked, partially

covered. Her face was obscured

by a jacket. As a journalist, I can’t

change the scene, so I can’t move

the jacket to reveal her identity. I

have the photos of what I saw.”

This of course differs from the

work of investigators, who would

collect and preserve physical

evidence, take measurements and

statements, and document the entire

scene and each piece of evidence

photographically.

Bodies of civilians who died during the evacuation of Irpin when Russian troops opened mortar and artillery

fire on them. Irpin, Kyiv region, Ukraine, March 6, 2022. © Maxim Dondyuk.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 53

Picturing Atrocity

MORAL PRESSURE

But the photojournalistic work

operates on many levels. In addition

to their potential evidentiary worth,

Douglas sees photos as uniquely

powerful in inciting an emotional

response—a moral outrage—that

presses for legal action. “We have

these images coming out of Ukraine,

for instance, the pregnant woman

who was injured by the rocket attack

[in Mariupol] and ended up dying

and losing the fetus. That had an

incredibly galvanizing capacity in

ways that words simply don’t—and

that can actually lead towards

mobilizing the necessary political will

to create war crimes trials.”

Yet the moral pressure on the

public also comes with a toll on

the frontline witnesses. Maxim

Dondyuk, a Ukrainian documentary

photographer who has observed

scenes of war crimes, says, “There

were a lot of things that broke me

down.” Kochetova confirms, “this has

been traumatizing. It’s personal. It

will affect me for decades.”

Dondyuk expresses a bigger

picture outlook: “For me, the

whole war is already a crime.”

He reiterates the point that photojournalists

are not investigators: “It’s

not my job. Yes, I have witnessed

war crimes and took as many photos

as could, but it’s not my role to dig

into that.” That is for prosecutors to

take up.

Alison Fitzgerald Kodjak, Acting

Global Investigations Editor with

the AP, makes a related point. She

has helped to head up War Crimes

Watch Ukraine, a joint project of

the AP and the PBS investigative

documentary series FRONTLINE,

that catalogs incidents of apparent

IHL violations. Influenced by, as she

says, “the flood of images” out of

Ukraine in the early days of the war,

Fitzgerald Kodjak and colleagues

developed this database—which

works with significant numbers

First responders and volunteers carry an injured pregnant woman from a maternity hospital that was damaged

by Russian shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 9, 2022. The woman and her baby later died. © Evgeniy

Maloletka/AP.

of photos but also other forms of

evidentiary records—to increase

public understanding. And while

Ukrainian prosecutors as well

as international law researchers

have expressed interest in the

documentation amassed, Fitzgerald

Kodjak is clear in stating, “this is

a journalistic enterprise. We aren’t

working to meet legal definitions.” In

short, there is a gap—one protected

as well as respected by many in the

field—between journalism and legal

application.

Even so, though he has no

experience with tribunals, Maloletka

nevertheless hopes his images may,

one day, provide a frontline view

that can hold Russian perpetrators

accountable in a court of law.

Ultimately, Dondyuk says, “I

hope that people not only see these

pictures, but feel it for themselves,

tear themselves from their cup of

coffee or glass of wine in their warm

refined world.” In short: Ignorance

and impunity are unacceptable.

THE FUTURE

The collection of evidence for potential

use in tribunals is set to outpace, by

an order of magnitude, the evidence

“I hope that people not only see these pictures, but feel

it for themselves, tear themselves from their cup of coffee

or glass of wine in their warm refined world.”

—Maxim Dondyuk, Ukrainian documentary photographer

amassed in Syria. As Betts says,

“you have the technology to collect

information, the political will to act on

that information, and the capacity of

society to assist this process.” The pace

will also be faster. Historically, such

trials could take years, even decades,

to come to fruition. We are now likely

to witness prosecutions that feel closer

to “real time.”

And as Dondyuk states of his current

work, “I’m not a war photographer.

When the war in Ukraine is over, I will

return to my artistic projects not related

to war, and definitely won’t continue

covering conflicts in other countries.

But this is my country now and I feel

that this is my duty to capture this

historical moment for the present and

the future.”

With gratitude to all in this essay who

gave time for an interview or allowed use

of imagery.

54 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

A Home for Global Documentary

Photo by Jean Ross from Displaced

Social Documentary Network

SDN Website: A web portal for

documentary photographers to

create online galleries and make

them available to anyone with an

internet connection. Since 2008,

we have presented more than

4,000 documentary stories from

all parts of the world.

www.socialdocumentary.net

ZEKE Magazine: This bi-annual

publication allows us to present

visual stories in print form with indepth

writing about the themes

of the photography projects.

www.zekemagazine.com

SDN Salon: An informal gathering

of SDN photographers to

share and discuss work online.

Documentary Matters:

An online place for photographers

to meet with others involved with

or interested in documentary

photography and discuss ongoing

or completed projects.

SDN Education: Leading

documentary photographers and

educators provide online learning

opportunities for photographers

interested in advancing their

knowledge and skills in the field

of documentary photography.

SDN Reviews: Started in April

2021, this annual program brings

together industry leaders from

media, publishing, and the fine

art community to review work of

documentary photographers.

ZEKE Award: The ZEKE Award

for Documentary Photography

and the ZEKE Award for Systemic

Change are juried by a panel of

international media professionals.

Award winners are exhibited

at Photoville in Brooklyn, NY and

featured in ZEKE Magazine.

Join us!

www.socialdocumentary.net

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 55

Interview

Karnak Temple, Egypt,

2023. Photo by Betsy

Kissam.

CHESTER HIGGINS

Chester Higgins, Jr. has spent over five

decades documenting the African American

experience, past and present. Born in

Fairhope, Alabama, Higgins worked as a

photographer at the New York Times for nearly

forty years. Published collections of his photography

include Black Woman; Feeling the Spirit:

Searching the World for the People of Africa;

Elder Grace: The Nobility of Aging; Echo of the

Spirit: A Photographer’s Journey; and his latest

book, Sacred Nile.

By Daniela Cohen

Daniela Cohen: I’d love to hear

more about how your journey into

photography started?

Chester Higgins: My beginning of photography

was accidental or just fortuitous.

I was a business management major at

Tuskegee and needed a photographer

for display ads in the newspaper. This

photographer had missed a deadline, so

I drove to his house.

Some photographs on his wall struck

me because they were photographs of

poor people, very dignified people.

They reminded me of the dignity of

people from my hometown.

It made me think wow, the image validates

whatever is showing. Most people

of color did not have money to go for a

formal sitting, so I thought, what if I could

give my great aunt and uncle a picture

of themselves to hang on their wall? But

I didn’t know how to make photographs,

so I asked this man to teach me.

A year later, I started making pictures.

I had them framed and took them

down to my great aunt and uncle and

placed them on their wall. My reward

was seeing their faces light up when

they recognized that they themselves

were worthy enough to be on their

walls. Not that they felt any inadequacy

about being themselves, it’s just something

they never thought about.

Essentially, validation is what I’ve

always done with my camera. I started

out with a love for my immediate family.

But it’s been consistently a love

for people who look like me and who

experience the same experience.

I didn’t try to show how badly

Black people are suffering. That sort of

photography sacrificed the humanity

of the people on the altars of racism,

and I refuse to be a party to that sort of

sacrifice. I want my images to be good

food for the mind. It’s very important you

balance out your imagery by using both

the head and the heart. And that’s what

I’ve always done.

DC: It sounds like you’ve been consciously

shifting the narrative that’s

being put out there by the choices that

you’re making.

CH: I cannot do away with the racist

images that everybody has been producing.

What I can do is add another

perspective, so that people will notice

another view as well. So, the spirit

that allowed me to be at the New York

Times for almost 40 years and to apply

change in that paper. I was not the only

photographer there, but I was one who

consistently felt it was my duty to broaden

the view for New York Times readers of

people who look like me. And it being

a paper for decision makers, that was a

very important place to be.

DC: I’m curious about the idea of your

photography giving visual expression to

your personal and collective memories.

Could you talk more about that and how

your photos are connected to themes of

place and identity?

CH: Living is very ethereal—like smoke

from a cigarette. We certainly produce

it, but as smoke, it disappears. So, on

a very personal level, my photographs

are another aspect of keeping a journal.

I keep a journal to unload what has

happened during the day and to have

that as a record that today actually

happened and then as another record of

how I internally process today.

I also tried to get the smoke of the

reality of people in a time before me.

This was a 10-year project looking at

historical photographs made of my

people by other photographers, 99%

White. I spent years going back and

forth to the Library of Congress, going to

see the FSA photographs, going through

the archives of Black colleges or universities

and public libraries. And then

doing more primary research by trying

to locate the family historian in different

communities to see what they had in

their shoeboxes underneath the bed. I

looked for the pictures that I would have

made. That had the same sensitivity that

I would have had, had I been on-site.

I didn’t want to take anybody else’s

pictures though, so I came up with an

idea that I needed a nice, big negative.

I started shooting four by fives with a

light stand that I took with me. I would

have pictures that I fell in love with and

copied. Those copies gradually grew to

many hundreds of contact sheets. And

eventually I was able to do a book called

Some Time Ago: A Historical Portrait of

Black Americans from 1850–1950.

DC: Can you tell me about what first

took you to Africa?

CH: In America, as a Black person, you

are convinced that you’re not American

because you’re not accepted. Your

sense of history comes from people

who despise you, which means that

it can only be warped. As a student

with a minor in sociology, I understood

that if I was going to find out about the

multiplicity of who I and we are as a

people, I had to create my own sources.

And those sources had to be in Africa

because the American academy had

already proven inadequate to that task.

I started spending summers in Africa

hanging out with my ‘cousins’ to learn

from their side. I learned Asante culture

in Ghana, Islamic and Wallof culture in

Senegal, Amharic culture in Ethiopia. I

had a job that took me to Egypt in 1973,

but then the October war broke out,

and I was stuck for another four weeks.

It would turn out to be great for me

because I got a chance to spend more

time at the museum and antiquity sites

and interrogate these things in front of

me that I had had no idea existed, that

no history book told me about. All that

56 / ZEKE SPRING 2023

“There is no one like you” a couple’s passionate embrace.

Brooklyn, New York 1987. © Chester Higgins.

All Rights Reserved.

interrogation is part of the memories,

the memories coming back alive only

because there is physical evidence that

remains of those previous lives that make

up the experience of the African people.

DC: Tell me about the inspiration behind

your latest book, Sacred Nile.

CH: It’s a product of five decades of

work that looks at how the Nile as a

migratory bridge connected Ethiopia,

Sudan and Egypt and how it shares its

cultures back and forth. It’s looking at the

earliest remnants of culture, that belief in

the sun and the sky that was developed

by Ethiopians migrating down the river

into Sudan and then further migrating

into ancient Egypt. And then over time,

after 7,000 years, it reversed.

The ancient nature religion of Egypt,

Ethiopia and Sudan bifurcated and

became the patriarch religions of the

Old Testament, the New Testament and

Islam. So 7,000 years earlier, what

went downstream, 7,000 years later

something else comes back upstream.

In Feeling the Spirit, I’m trying to

show that we all have similarities. We

have our differences, but the differences

are usually nationalistic, not cultural.

And the cultural differences hold us

together. So, in the book, I’ll have a

picture of something that you recognize,

say a mother. She could be in Alabama

and in the next picture, she’s in Ghana.

The next picture, she may be in Nigeria.

With Sacred Nile, my hope

is that we recognize our history.

Because it’s not something that we

have been taught…. I tell people,

slavery is not the beginning of our

history. Slavery is an interruption of

our history.

DC: It seems one of your main

goals is capturing the spirit that’s

present in all things, that transcends

the labels that we put on ourselves

and each other. Could you tell me

more about why that’s so important

to you and the techniques you use

to bring that out in your work?

CH: I had an out-of-body death

experience when I was nine years

old. Early in the morning, I hear

this sound in my room and it’s in

my head not in the air and I open my

eyes and see this big circle of white

light on the wall. And this Black man

standing in the middle with his hands

raised, wearing a toga. He begins to

walk toward me and says, “I come for

you,” and I’m scared but I’m pissed.

I’ve heard about this angel of death,

but I’m only nine years old. And what

the fuck, I gotta die? So, I scream. My

parents and grandparents came in. My

mother was at the foot of the bed holding

my hands and I began to feel I was

ascending and she was getting smaller.

She kept rubbing my hands so viciously

that at some point, it must have worked

because I came back down. But when I

was seeing her getting smaller, it made

me realize this is what dying is like.

Then I begin to intuitively realize there’s

a parallel thing going on here. Because

I’m dying and she’s there living and

I’m beginning to get a feel for a whole

other kind of reality. So, I put that away,

but I’ve always benefited from that.

Whenever I see something, I know that

there is something else behind it. What

it appears to be is only one dimension

of it. But the other dimensions that

are really pulling the strings going on

behind it are a lot more interesting.

DC: So, when you’re making the photographs,

it’s in the multi-dimensional

reality and you’re allowing that which is

beyond the surface to emerge and that’s

what you’re capturing.

CH: At that moment when the shutter is

pressed, I have to make that decision.

Every photographer has to make that

decision based on whatever their reality

is about. My reality is the same as

yours on one level, but there’s something

underneath that speaks to me. There’s a

certain timeless quality to my imagery,

and it cannot be arrested. The simplest

arrested photograph is a fashion

photograph. It gets arrested in time. I’m

always trying to create an image that

does not get arrested in time. I’m surfing

on the spirit.

Solar Aksumite Obelisk in Ethiopian highlands stands as a Royal tomb marker. 2016. © Chester Higgins. All

Rights Reserved.

ZEKE SPRING 2023/ 57

BOOK

REVIEWS

CHRIS KILLIP

Thames and Hudson, 2023

256 pages / $75

The book opens with two softly lit,

full bleed head and shoulder portraits

of a young brother and sister.

The faces stare back at us, one (fouryear

old Chris), with a slight smile, a

hint of rascal, open with possibility. The

other, (five-year old Anthean) is already

set, tinged with sadness, maybe a bit of

anger, resigned to a life without possibilities.

It is impossible not to wonder

what happened to them.

This begins our journey through Chris

Killip, the aptly titled monograph of one

of Britain’s most important, but least well

known, documentary photographers.

Killip’s black and white images, a mix of

portraiture and candid reportage, are an

empathetic rendering of working class

life in 1970s and 1980s Britain when

jobs disappeared and communities were

destroyed by gentrification and then a

spiral into poverty.

The book is divided into four chapters

that roughly mirror Killip’s main projects:

work from the Isle of Man; the Edgelands,

which included projects from Askam,

Skinninggrove and the seacoalers from

Lynemouth; the North Country; and The

Last Stories, a hodgepodge of work made

later in Killip’s life. Each section features

an essay either about Killip or his work.

Killip’s images do what traditional

documentary photography does best:

create an origami of time as past

present and future converge and unfold

like warped spacetime. He describes

photographs as “a chronicle of a death

foretold’ and that awareness is clear in

his photographs. It is not only the death

of the person, but the death of a way of

life. These are people to whom history

happened.

Killip photographed with a large

format camera, not the traditional 35mm

of his peers. The detail and expanded

tonality from a large negative, while not

so apparent in the book, is on display in

the amazing retrospective and traveling

exhibit at the Photographer’s Gallery

Cookie in the snow, Seacoal Camp, Northumbria, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

in London, curated by Ken Grant and