Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

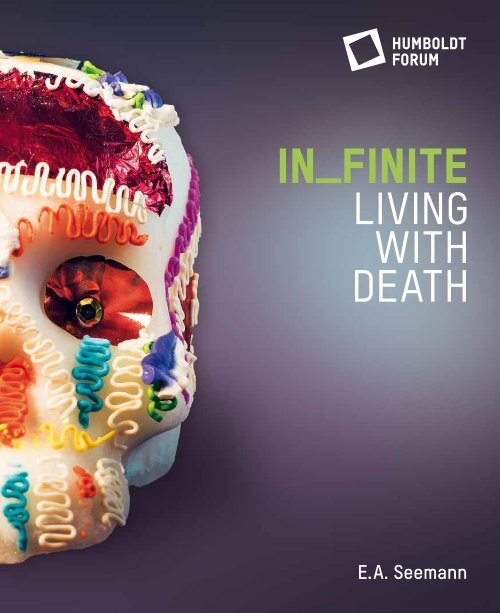

<strong>IN</strong>_F<strong>IN</strong>ITE<br />

LIV<strong>IN</strong>G<br />

WITH<br />

DEATH

<strong>IN</strong>_F<strong>IN</strong>ITE<br />

LIV<strong>IN</strong>G<br />

WITH<br />

DEATH<br />

If we tell the story of the universe <strong>with</strong>in a timespan of<br />

twenty-four hours, Homo sapiens appears only in the final<br />

second. According to scientific calculations, the universe<br />

is 13.8 billion years old. The first traces of life in the form of<br />

bacteria-like single-celled organisms date back approximately<br />

3.8 billion years. Homo sapiens has been verifiably<br />

living on Earth for some 300,000 years.<br />

pp. 2–3<br />

Star cluster Westerlund 2<br />

(image taken <strong>with</strong> the Hubble Space Telescope)<br />

The star cluster is located in the Milky Way and is<br />

approximately 20,000 light years away from Earth.<br />

Its estimated age is one to two million years.<br />

pp. 4–5<br />

Cirrus Nebula<br />

(image taken <strong>with</strong> the Hubble Space Telescope)<br />

The Veil Nebula is approximately 2,100 light years away from<br />

Earth and is one of the best-known remnants of a supernova.<br />

This occurred when a star exploded some 8,000 years ago.<br />

pp. 6–7<br />

The centre of the Milky Way glowing in dust<br />

(image taken <strong>with</strong> the Spitzer Space Telescope)<br />

The Milky Way is our home galaxy, <strong>with</strong>in which the solar<br />

system containing Earth is located. It consists of hundreds of<br />

billions of stars and is approximately 13.6 billion years old.<br />

pp. 8–9<br />

Earthrise<br />

Earth, the place of origin and home of all living creatures<br />

known to date, was formed approximately 4.6 billion years<br />

ago. The photograph was taken from the Apollo 8 spacecraft<br />

in 1968.

CONTENTS<br />

14 Foreword<br />

Hartmut Dorgerloh<br />

16 Introduction<br />

Detlef Vögeli<br />

THE HEREAFTER<br />

22 IS THERE LIFE AFTER DEATH?<br />

24 Four Ways to Live for Ever<br />

Stephen Cave<br />

29 Contemporary Notions of the Hereafter<br />

Félix Ayoh’Omidire / Esther Hirsch / Kadir Sanci /<br />

Jasmin El-Manhy / Vilwanathan Krishnamurthy / Thien My /<br />

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche / Bhai Kashmir Singh / Pir Hasan Doğan /<br />

Mario Vázquez / Mark Benecke / Emil Kendziorra<br />

54 Dead and Alive<br />

Klaus Bo<br />

DY<strong>IN</strong>G<br />

70 WHAT IS A GOOD DEATH?<br />

72 <strong>Death</strong> and Dying in Non-Western Cultures<br />

Helaine Selin and Robert M. Rakoff<br />

75 World <strong>Death</strong> Conference<br />

Rafael Ernesto Mamanché González / Noreen Chan /<br />

Kodjo Senah / Aysel Erki / Anurag Hari Shukla / Myriam Rios /<br />

Mike Kelly / Hadley Vlahos / Bukelwa Sigila / Rachel Ettun /<br />

Patrice Dwyer / Thích Thiện Nguyện<br />

DEATH<br />

100 WHAT HAPPENS AT THE F<strong>IN</strong>AL MOMENT?<br />

102 “The last wave of elec trical discharge before death is<br />

an enormous event”<br />

Interview <strong>with</strong> Jens Dreier<br />

THE MORTUARY<br />

110 WHAT DOES HUMAN DIGNITY MEAN BEYOND DEATH?<br />

112 <strong>Living</strong> <strong>with</strong> the Dead. <strong>Living</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Death</strong><br />

Liv Nilsson Stutz<br />

118 Care for the Dead<br />

123 Autopsy of the Conditions of <strong>Death</strong> across the Globe<br />

136 The Names behind the Numbers<br />

148 “It’s inhumane to let people die this way”<br />

Interview <strong>with</strong> Cristina Cattaneo<br />

GRIEF<br />

152 HOW DO WE F<strong>IN</strong>D SOLACE?<br />

154 “Grief is a messy, painful affair”<br />

Interview <strong>with</strong> Julia Samuel<br />

OPEN END<br />

160 WHAT WILL REMA<strong>IN</strong>?<br />

162 On the End of Evolution<br />

Matthias Glaubrecht<br />

168 Cabinet of Extinct and Endangered Species<br />

180 The Democracy of Species<br />

Robin Wall Kimmerer<br />

184 “The distinction between human history and natural<br />

history is no longer tenable”<br />

Interview <strong>with</strong> Dipesh Chakrabarty<br />

188 Credits

<strong>IN</strong>TRODUCTION<br />

LIV<strong>IN</strong>G WITH DEATH.<br />

A HUMAN DRAMA<br />

Detlef Vögeli<br />

“This is the paradox: he [man] is out of nature<br />

and hopelessly in it; he is dual, up in the stars and yet<br />

housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that<br />

once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to<br />

prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien<br />

to him in many ways – the strangest and most repugnant<br />

way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay<br />

and die.” 1<br />

Ernest Becker, The Denial of <strong>Death</strong><br />

Homo sapiens is probably the only animal that knows it<br />

will die. Only humans are aware of their own existence –<br />

and therefore also of their vulnerability and transience.<br />

We know that our life is finite; and at the same time, like<br />

all living things, we have an instinctive drive to survive.<br />

We must live <strong>with</strong> death.<br />

The cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker argued that<br />

the fear of death determines all human behaviour. This<br />

fear and the longing for immortality are the main driving<br />

forces of human activity. Both the noblest and the most<br />

repulsive forms of human endeavour stem from the<br />

awareness that we are mortal. The knowledge of death<br />

has shaped the course of human history, giving rise to<br />

culture, civilization, science and world views. Humans<br />

have woven stories and rituals to make the inexplicable<br />

comprehensible, the unbearable bearable, and to give<br />

meaning to our finite lives.<br />

The scientific-biological understanding of physical<br />

death as the end of human existence that prevails in<br />

enlightened, secularized societies is more recent.<br />

According to his standard work on the history of death<br />

published by French historian Philippe Ariès in 1977,<br />

death had been “expatriated” from modern Western society<br />

in the course of the 20th century: “Until the age of<br />

scientific progress, human beings accepted the idea of<br />

a continued existence after death.” 2 <strong>Death</strong>, he states, is<br />

integrated into the cultural narratives of society, a part of<br />

the social world of meaning. Ariès describes pre-modern<br />

death as “tame” and modern death as “wild”. 3<br />

Despite all scientific progress, death remains a phenomenon<br />

that is beyond our understanding. We know<br />

less about the moment after death than about anything<br />

else. <strong>Death</strong> is perhaps the last inaccessible frontier of<br />

knowledge-based society.<br />

Talking about death requires allowing and enduring<br />

polyphony and ambiguity. To ponder one’s own death<br />

and finitude is to reflect on the human relationship to<br />

the world, a locating of our lives <strong>with</strong>in the community,<br />

<strong>with</strong>in society, <strong>with</strong>in the universe. When we talk about<br />

ideas of life <strong>with</strong> and after death, we are talking about<br />

world views – beyond right and wrong. The knowledge<br />

of the transience and fragility of human life and all living<br />

things confronts us <strong>with</strong> existential and ethical-moral<br />

questions.<br />

The contributions in this book are an invitation to approach<br />

the finiteness of life from various perspectives.<br />

They offer insights into different worlds of imagination<br />

and experience. Documentary contributions from the exhibition<br />

in_finite. <strong>Living</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Death</strong> are complemented by<br />

introductory essays and photo spreads. The focus is on<br />

the question of our personal and social relationship <strong>with</strong><br />

finite nature. The publication spans an arc from individual<br />

death to the impending extermination of the species<br />

Homo sapiens as a result of the sixth mass extinction.<br />

Historical and cultural evidence suggests that humans<br />

have always done everything possible to postpone<br />

or overcome death – both factually and symbolically<br />

( Stephen Cave, p. 24).<br />

In many cultures, death was and is understood as a<br />

change of state, a transition into another form of existence.<br />

The promise of a life in the hereafter provides<br />

meaning and orientation – be it the idea of a paradise<br />

in Islam or Christianity, a moks· a in Hinduism, nirvana in<br />

Buddhism, or an ancestral world in the Yoruba religion.<br />

The aim is to lead a good life according to certain rules,<br />

to follow one’s personal dharma, to live in a God-conscious<br />

way. <strong>Death</strong> embeds the individual <strong>with</strong>in a larger narrative,<br />

<strong>with</strong>in a cosmology that provides a framework for<br />

behaviour and promises existence in a better world as a<br />

reward (Contemporary Notions of the Hereafter, p. 29).<br />

Dying and death are universal facts; the way we deal <strong>with</strong><br />

them is culturally and individually shaped (Helaine Selin,<br />

Robert M. Rakoff, p. 72). What counts in the last days,<br />

hours and minutes before death? What do people regret<br />

on their deathbed? What comforts them? How universal<br />

is the process of dying? What role do cultural and reli gious<br />

beliefs play at the end of life? Twelve individuals who<br />

accompany others to death at the end of their lives talk<br />

about their experiences and rituals (World <strong>Death</strong> Conference,<br />

p. 75).<br />

The neurologist and stroke researcher Jens Dreier<br />

has observed what happens in the brain during the final<br />

phase of dying. He speaks of the final wave of release<br />

before death. What happens after death at the level of<br />

consciousness remains a mystery: “Everything that is<br />

accessible to us happens while the patient is still alive.<br />

What might happen afterwards is not accessible to science”<br />

(Jens Dreier, p. 102).<br />

Rituals can provide comfort during the process of dying<br />

and beyond death. The bioarchaeologist Liv Nilsson<br />

Stutz examines how the universal crisis of death is dealt<br />

<strong>with</strong> in different cultures and the significance of the ritual<br />

care of the corpse. Behind the diversity of funeral rituals<br />

in different cultures lies a universal human need in the<br />

face of death. Beneath the surface, she explains, “we<br />

also discover that our vulnerability is the same, and the<br />

need to make sense of the world and what is happening<br />

to us is a shared human condition. It is in these moments<br />

that we can see ourselves in the other, and the other in<br />

ourselves. It is encounters like this that we can begin to<br />

grasp our shared humanity and the responsibility that<br />

that entails” (Liv Nilsson Stutz, p. 112).<br />

<strong>Death</strong> unites us – and death divides us. Although no<br />

one is privileged enough to escape physical death, we<br />

are not all equal in the face of death. Social and geographical<br />

origins determine statistical life chances.<br />

<strong>Living</strong> conditions are also reflected in the conditions of<br />

death. Hygiene, affluence and medical care, as well as<br />

social and political conditions, determine how directly<br />

we are at the mercy of death. We are all living longer than<br />

ever before. However, the gain in lifespan is unequally<br />

distributed. People born in Nigeria, for example, have<br />

a life expectancy of less than fifty-three years, while in<br />

Germany it is currently over eighty years. People in the<br />

poorer regions of the world are already, and will continue<br />

to be, the main victims of climate change (Infographics,<br />

p. 123).<br />

We count the dead and investigate the causes of<br />

death in order to better protect human life in the future.<br />

According to international humanitarian law, the dead<br />

must be identified and buried. The forensic anthropologist<br />

Cristina Cattaneo has been working since 2013 to<br />

identify the nameless people who drowned in the Mediterranean<br />

Sea while attempting to flee to Europe. Identifying<br />

the dead is a question of human dignity – but it<br />

is also important for the bereaved so that they can have<br />

certainty and say goodbye (Cristina Cattaneo, p. 148).<br />

In psychology, “ambiguous loss” is the phenomenon of<br />

losing a loved one <strong>with</strong>out knowing whether or not they<br />

are still alive. This uncertainty delays the grieving process<br />

and can lead to unresolved grief. “Grief is the most<br />

intense emotional pain we know,” explains the psychotherapist<br />

Julia Samuel. She has been accompanying<br />

people in grief for more than three decades. In an interview,<br />

she explains how we can live <strong>with</strong> this pain – and<br />

why we should once again give death and mourning more<br />

space in our society (Julia Samuel, p. 154).<br />

However, death does not fit into an enlightened, rational<br />

world – not into the idea of the mastery of nature,<br />

according to which there are no natural limits that cannot<br />

be overcome at some point by science and technology.<br />

The successful development of Homo sapiens is also a<br />

history of this idea. The discovery of fire gave humans<br />

more energy than their muscles could provide. Today,<br />

16 <strong>IN</strong>TRODUCTION DETLEF VÖGELI 17

we burn as much oil, natural gas and coal worldwide in<br />

a single day as was created over the course of 500,000<br />

years. 4 These fossil fuels are the drivers of economic<br />

growth and prosperity – a finite resource, the product<br />

of plants and animals that died millions of years ago.<br />

Humans are moving both <strong>with</strong>in and beyond their natural<br />

limits. They use three-quarters of the Earth’s surface<br />

and two-thirds of its oceans and have thus become a<br />

planetary force that is upsetting the balance of natural<br />

processes that are billions of years old. An estimated<br />

one million species are threatened <strong>with</strong> extinction. The<br />

decline of biodiversity also threatens the very basis of<br />

human life (Matthias Glaubrecht, p. 162). We have become<br />

our own gravediggers.<br />

Are we thus at the beginning of the end of human<br />

history? The Indian historian Dipesh Chakrabarty is “not<br />

optimistic, but hopeful” – because human beings are<br />

capable of learning. He suggests broadening the global<br />

perspective on the world to include a planetary view that<br />

decentres humanity and understands its history as part<br />

of natural history (Dipesh Chakrabarty, p. 184).<br />

The stories we tell about ourselves and our relationship<br />

to the world are among the most powerful tools we<br />

have as humans. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a plant ecologist<br />

and member of the Potawatomi people, calls for combining<br />

Indigenous wisdom <strong>with</strong> science to reform our<br />

relationship <strong>with</strong> nature. She wants to bring ancient stories<br />

to life, stories in which humans do not stand at the<br />

top of a hierarchy as the purported crown of creation,<br />

but rather exist in a symbiotic interdependence <strong>with</strong> all<br />

living things; as part of the biosphere, dependent also on<br />

the flourishing of the non-human living world (Robin Wall<br />

Kimmerer, p. 180).<br />

How can we live <strong>with</strong> the awareness of our natural<br />

transience and the vulnerability of all living things? How<br />

can we live better <strong>with</strong> the responsibility that comes<br />

<strong>with</strong> this knowledge? What cultural narrative helps us to<br />

channel our fear of death in constructive ways? Or, in the<br />

words of Ernest Becker: “What is life-enhancing illusion?”<br />

5 – for us personally, as a community, as a society,<br />

as a species, and for the planet?<br />

This book, like the exhibition, is rich in experiential<br />

knowledge. Many thanks are due to the people from<br />

Berlin’s urban society who shared their ideas about death<br />

and a piece of their lives <strong>with</strong> us, as well as to the palliative<br />

care providers from around the world for sharing<br />

their touching and enriching encounters, for giving us<br />

insight into their experiences of caring for the dying<br />

and thus a “glimpse of human nature” (Noreen Chan,<br />

p. 78). These conversations and encounters would not<br />

have been possible <strong>with</strong>out the support of numerous<br />

medi ators, translators and interviewers from around the<br />

world. My express thanks go to all the authors for their<br />

contributions and expertise.<br />

My special thanks go to the curatorial team, my “Circle of<br />

Trust”, Gesine Last and Jan Zappe, as versatile contributors<br />

and active thinkers for their invaluable support on<br />

various levels, Kathrin Haase for her support in researching<br />

the protagonists for the World <strong>Death</strong> Conference, and<br />

Yvonne Zindel for researching the diverse protagonists<br />

from Berlin’s urban society <strong>with</strong> their different conceptions<br />

of the hereafter.<br />

Last but not least, my thanks are due to the Humboldt<br />

Forum Foundation: General Director Hartmut Dorgerloh for<br />

his great trust, the exhibition team led by Anke Daemgen,<br />

David Blankenstein and Frank Meißner, as well as Sibylle<br />

Kussmaul and Marc Wrasse from the Education and<br />

Outreach Department for their support, Susanne Müller-<br />

Wolff as the person responsible for the publication for<br />

her careful planning, and Barbara Martinkat for her stylish<br />

image editing.<br />

Thanks also go to Sahar Aharoni, whose skilful design<br />

has made this book look so inviting, to Barbara Delius for<br />

decisively enhancing the publication <strong>with</strong> her critical and<br />

constructive view of the big picture and her unerring eye<br />

for detail, and to Danko Szabó for his copy editing.<br />

1 Ernest Becker, The Denial of <strong>Death</strong>, London 1973, p. 26.<br />

2 Philippe Ariès, Philippe Ariès, The Hour of Our <strong>Death</strong> [1977], trans. Helen<br />

Weaver, New York 1981, p. 95.<br />

3 Ibid., p. 610.<br />

4 Jürgen Renn, “Das Anthropozän und die Geschichte des Wissens”, 28 February<br />

2022; ww.br.de/mediathek/video/prof-dr-juergen-renn-das-anthropozaen-und-die-geschichte-des-wissens-av:5dce82a1ebea9c001ad6f8bd<br />

[accessed on 30 January 2023].<br />

5 Becker 1973 (see note 1) p. 158 [emphasis in the original].<br />

18 <strong>IN</strong>TRODUCTION DETLEF VÖGELI 19

DEATH<br />

WHAT HAPPENS<br />

AT THE F<strong>IN</strong>AL<br />

MOMENT?<br />

What happens at the moment of death? Does the light at<br />

the end of the tunnel actually exist, and where does it come<br />

from? When is a person dead?<br />

<strong>Death</strong> is the final certainty in life. But when exactly a person<br />

is dead remains uncertain – the time of death cannot be<br />

clearly determined scientifically. What happens at the<br />

moment of (brain) death on the level of consciousness is<br />

a mystery. There are, however, insights into what happens<br />

in the brain during the last moments of life. Here, observations<br />

from neuroscience about the great wave that ushers<br />

in death and reports from people <strong>with</strong> a near-death experience<br />

are similar.

“THE LAST WAVE<br />

OF ELEC TRICAL<br />

DISCHARGE BEFORE<br />

DEATH IS AN ENOR-<br />

MOUS EVENT”<br />

Jens Dreier<br />

In an interview <strong>with</strong> Gesine Last und Detlef<br />

Vögeli, the experimental neurologist Jens Dreier<br />

talks about processes in the brain in the last<br />

minutes of life.<br />

You’re a neurologist and a professor at the<br />

Center for Stroke Research in Berlin. How did<br />

you become an expert in the physiological processes<br />

of dying?<br />

The Center has very many patients who have had<br />

strokes – which is an area I’ve been working on for many<br />

years. There are two main types of stroke. The ischaemic<br />

ones result from insufficient blood flow. And the haemorrhagic<br />

ones are a consequence of blood leaving the<br />

circulatory system and accumulating in the brain’s tissue<br />

or on its surface. I’m especially interested in this second<br />

type of stroke. Cerebral haemorrhages are caused, for<br />

example, by the rupture of an aneurysm. At the rupture,<br />

blood leaves the circulatory system and accumulates on<br />

the brain surface. This initial event is very dangerous<br />

for the patient. In addition to the damage that can occur<br />

immediately from the bleeding itself, there will often be<br />

subsequent strokes for about two weeks thereafter.<br />

These subsequent ones are ischaemic, and are known as<br />

delayed strokes. The mechanism underlying them is very<br />

complex, and that is my actual area of research. Delayed<br />

strokes worsen patient outcomes considerably. A major<br />

problem is that patients are often not conscious when a<br />

delayed stroke develops, which makes it extremely difficult<br />

to start treatment at the right time.<br />

What does that have to do <strong>with</strong> dying?<br />

The processes that occur during a stroke also occur in<br />

a similar form during dying. If someone suffers a stroke,<br />

nerve cells in a certain part of the brain die. If the whole<br />

person dies, all the nerve cells in their brain die. Our research<br />

includes animal studies as well as studies in patients<br />

in the intensive care unit (ICU), where we perform<br />

invasive neuromonitoring. For example, we continuously<br />

record the electrical brain activity. If certain changes in<br />

electrical voltage occur, they tell us that the patient is<br />

at risk of delayed stroke at that moment. Some of the<br />

patients we have monitored at Charité in Berlin or at our<br />

partner facility at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio<br />

have died during monitoring from complications of their<br />

severe underlying disease. We were thus able to record<br />

what happens in their brains when they die. The processes<br />

that take place during a stroke and during dying<br />

are closely related and can therefore be measured using<br />

the same methods.<br />

What processes do you mean?<br />

First of all, it is important to note that there are certain<br />

elements that always occur during dying, even if they do<br />

not always occur in the same order. The most striking<br />

feature of our recordings are enormous waves, the socalled<br />

“spreading depolarizations”, which I will describe<br />

in more detail in a moment. They occur during strokes<br />

and also during death. Although they are not the only<br />

mechanism, they are the most important in the transition<br />

from life to death.<br />

You said the sequence isn’t always the same.<br />

But does the process of dying still follow something<br />

like a script?<br />

Yes. There is always a phase in which the neurons are<br />

still alive but transitioning to a different functional state.<br />

And then there is the phase in which they actually die off,<br />

which takes a relatively long time. In ICU patients, the<br />

major differences are between death caused by cardiocirculatory<br />

arrest and death caused by death of the brain<br />

alone, although the rest of the body continues to live. The<br />

latter is often simply called “brain death” and refers to<br />

a condition in which the patient is ventilated and has an<br />

intact circulation and only the brain is no longer supplied<br />

<strong>with</strong> blood.<br />

Cerebral swelling is the reason for this. Because the<br />

brain doesn’t have much room to expand in the cranium,<br />

pressure rises in the brain. And when brain pressure exceeds<br />

systemic blood pressure, blood flow to the brain<br />

fails, which is incompatible <strong>with</strong> life for that individual<br />

although the rest of their body lives on in a biological<br />

sense. Both cardiovascular arrest and brain death are<br />

associated <strong>with</strong> spreading depolarizations but their patterns<br />

are quite different.<br />

What time frame are we talking about for the<br />

wave and for the death of neurons in the brain?<br />

When there is a sudden cardiac arrest and the heart<br />

stops beating completely, there may be a period when<br />

there is even some increase in brain activity. This ends<br />

after 30 or 40 seconds. Crucially, the activity ends by<br />

strongly inhibiting the neurons, but they remain alive and<br />

electrically charged. In this way, the cells save energy.<br />

However, they continue to consume a little energy until<br />

at some point they no longer have enough. Then the<br />

energy-dependent ion pumps in the cell membranes fail,<br />

and a tsunami of depolarization begins. Importantly, this<br />

tsunami is not death itself, but rather the wave triggers<br />

processes that lead to neuronal death <strong>with</strong> a significant<br />

time delay. In an adult <strong>with</strong> a normal body temperature,<br />

we would say that in a sudden cardiac arrest <strong>with</strong>out<br />

resuscitation, neurons begin to die about five to ten minutes<br />

after the circulatory arrest.<br />

Could we say it’s like a program that follows a<br />

certain logic?<br />

Yes, I think one could describe it as a type of program.<br />

A death that occurs naturally typically follows the cessation<br />

of cardiovascular and respiratory activity. If, for<br />

example, breathing stops first, the heart also stops working<br />

after a certain delay because it is no longer supplied<br />

<strong>with</strong> the oxygen necessary for pumping. All the organs,<br />

including the brain, will then no longer be supplied<br />

<strong>with</strong> blood. That is why resuscitation is so important. If<br />

someone pushes the chest down forcefully and rhythmically,<br />

restoring at least a little circulation that pumps a<br />

small amount of blood through the brain, it makes a big<br />

difference. Minimal blood supply to the brain through<br />

resuscitation delays neuronal cell death. The earlier resuscitation<br />

is started, the greater the likelihood that the<br />

person’s nerve cells will survive.<br />

How do the nerve cells respond when circulation<br />

stops?<br />

First of all, they briefly seem to show a changed rhythm.<br />

At this point, the nerve cells are not yet in a depressed<br />

state. Only after about 30 seconds are they then<br />

switched off. Although the inhibitory transmitters now<br />

dominate, tiny amounts of both excitatory and inhibitory<br />

transmitters continue to be released. An EEG (electroencephalogram)<br />

then shows a flatline, but this does not<br />

mean that nothing more happens during this phase. According<br />

to our measurements, another 13 to 266 seconds<br />

pass from the moment when no more brain activity can<br />

be detected to the point at which a spreading depolarization<br />

sets in, which implies an immense loss of electrochemical<br />

energy.<br />

A pivotal point.<br />

102 DEATH JENS DREIER 103

Absolutely. When the wave sets in, processes begin that<br />

are toxic for the nerve cells. The clock starts ticking. An<br />

enormous stress begins for the cells. For example, the<br />

nerve cells and their processes swell enormously, which<br />

you can observe under a two-photon microscope.<br />

What exactly happens when this wave is unleashed?<br />

This wave is truly a colossal event. Neurotransmitters are<br />

released en masse. There is actually no neurotransmitter<br />

that is not released during this phase. The wave spreads<br />

slowly throughout the brain. This releases a lot of electrochemical<br />

energy, which is converted into heat. At<br />

the front of the wave, there are a few action potentials,<br />

which are impulses that can also occur under normal<br />

conditions. Then there is utter silence. The simplest way<br />

to describe the wave is as a short circuit in a battery. The<br />

nerve cells lose their electrical charge <strong>with</strong> the wave.<br />

That means there’s no energy left to generate any more<br />

impulses. What I personally find important, however,<br />

is that this spreading depolarization is not the wave of<br />

death itself. That’s not the case. The wave induces toxic<br />

processes, after which it takes a while for the nerve cells<br />

as such no longer exists. In mechanistic terms, the occurrence<br />

of a vegetative state is connected <strong>with</strong> the fact<br />

that the cerebral cortex is considerably more susceptible<br />

than the brain stem to the development of a spreading<br />

depolarization.<br />

When does the process become irreversible?<br />

When the organelles of the depolarized nerve cells are<br />

so badly damaged that they can no longer function adequately<br />

even after energy is restored.<br />

So that’s the point of no return.<br />

Yes, but it is not simultaneous <strong>with</strong> the wave. The wave<br />

begins and you still have two or three minutes. Only then<br />

do the nerve cells begin to die. Energy is an apt image<br />

for me here. Our brains are normally full of energy. Each<br />

nerve cell is both a power plant that generates energy<br />

from oxygen and glucose, and an energy consumer.<br />

The energy produced in the power plants is stored and<br />

used to generate signal impulses. Normally, a very large<br />

amount of energy is stored, only a fraction of which<br />

is used in the form of impulses, or what are known as<br />

action potentials. But that’s still quite a bit. Although it<br />

a few minutes. If blood flow to the brain is not restored,<br />

all 86 billion of our neurons will eventually be completely<br />

discharged and eventually so poisoned that they will die.<br />

What does dying feel like? What do we know<br />

about it? You speak of an enormous wave.<br />

People also talk about a final great display of<br />

fireworks …<br />

The reports of patients who were resuscitated and<br />

survived are the only things we can rely on. A patient lies<br />

there, unconscious, and appears to be dead although<br />

that is not yet the case. Their heart no longer beats but<br />

their nerve cells are still alive. Around 15 percent of people<br />

who are resuscitated have a conscious experience<br />

during this period. There are various speculations about<br />

what might be responsible for near-death experiences.<br />

Such as?<br />

A relatively interesting thought is that there may be a<br />

surge of activity in the initial phase, a final flare-up, so to<br />

speak, before the spontaneous electrical activity of the<br />

brain comes to a halt. This surge of activity might have<br />

something to do <strong>with</strong> near-death experiences. What is<br />

migraine auras, however, also describe a type of tunnel<br />

vision and/or bright lights. The source of the aura is a<br />

wave, which is very similar to what occurs in a stroke or<br />

in the process of dying.<br />

Which phenomena are considered to be neardeath<br />

experiences?<br />

Notable features of near-death experiences include a<br />

sense of simultaneity, a sense of being in multiple places<br />

at essentially the same time, and the ability to be of different<br />

ages at the same time. That would fit in well <strong>with</strong><br />

a coordinated short-term process in the brain by which<br />

a great many nerve cells are – more or less simultaneously<br />

– activated and call up our (stored) memories at<br />

nearly the same time. A look back in time, when your life<br />

seems to flash before your eyes. Other phenomena include<br />

out-of-body experiences, although these can also<br />

be triggered in other contexts, such as during epileptic<br />

seizures or by magnetic stimulation of certain regions of<br />

the brain.<br />

To what extent are images like the white tunnel<br />

influenced by cultural and religious ideas?<br />

to die. If circulation and a supply of energy are restored<br />

after the onset of the wave, the process is entirely reversible<br />

up to a certain point in time and the nerve cells<br />

can also recover. In the case of a stroke, the waves can<br />

also spread far into healthy tissue <strong>with</strong> a normal blood<br />

supply, where they can have important signalling functions<br />

for the organism, so that their effects need not always<br />

be negative. It’s all very complicated.<br />

accounts for only 2 percent of the body’s weight, the<br />

brain uses 20 percent of our caloric intake to produce<br />

enough energy for its IT activities around the clock.<br />

In other words, as long as the body is at rest and not<br />

running a marathon, for example, the brain is the body’s<br />

greatest consumer of calories. That being said, much<br />

more energy is stored in the brain than is used at any<br />

given moment. Similar to a battery, energy is stored in<br />

also important is that different regions of the brain can<br />

be in various stages of the process of dying. One region<br />

might already show a spreading depolarization, whereas<br />

another might not yet be affected. Another possibility<br />

is that it is not actually the transitional phase from life<br />

to death that gives rise to near-death experiences but<br />

rather what happens afterwards if resuscitation is<br />

successful. What is also conceivable is that near-death<br />

Most studies on this topic tend to come from a Western<br />

cultural context. But I recently read a report from<br />

Sri Lanka, which has several religions in a relatively<br />

small geographic area. The researchers found different<br />

frequencies in the mention of near-death experiences,<br />

<strong>with</strong> a somewhat higher rate from areas <strong>with</strong> Christian<br />

influence. On the other hand, they reported such experiences<br />

from all the religions studied. Atheists, too, can<br />

Is there a point of no return?<br />

Yes, but this point is hard to define. For example, not all<br />

nerve cells die at the same time, because some are very<br />

vulnerable and others less so. That is why there can also<br />

be situations in which some nerve cells start dying but<br />

others are still alive. If resuscitation efforts are successful,<br />

the patient might lose some of their nerve cells<br />

and retain others. This, of course, is a crucial factor for<br />

the quality of life that can be achieved thereafter. One<br />

special variant here would be a vegetative state in which<br />

only the brain stem is capable of functioning. Respiration,<br />

circulation and a sleep-wake cycle are possible, but<br />

higher brain functions no longer work and the individual<br />

each individual nerve cell by separating ions across the<br />

cell membrane. It’s essentially the same thing that happens<br />

in a flashlight battery. Turning the torch on and then<br />

quickly off again would correspond to a nerve impulse.<br />

Turning the torch briefly on and off uses only a tiny fraction<br />

of the energy stored in its battery. You can repeat<br />

that for a long period of time before the battery loses its<br />

charge. In contrast to simple signal impulses, spreading<br />

depolarization is an event in which the neurons, meaning<br />

the “miniature batteries”, suffer a short circuit and<br />

essentially lose all their charge at once. This short circuit<br />

doesn’t take place everywhere at the same time, however,<br />

but instead migrates slowly through the brain from<br />

neuron to neuron, reaching ever more locations <strong>with</strong>in<br />

experiences arise while the brain is regenerating. In<br />

the aftermath of a successful resuscitation, there are<br />

patterns of electrical activity in the brain similar to those<br />

observed in the context of hallucinations from other<br />

causes. The question of near-death experiences constitutes<br />

a broad field.<br />

Many people report seeing a tunnel of white<br />

light. Are there scientific explanations for this?<br />

I find the white tunnel interesting because these types<br />

of light-related phenomena also occur in migraine <strong>with</strong><br />

aura. A typical migraine aura consists of a jagged ringlike<br />

image that usually begins in the middle of the field of<br />

vision and slowly extends outwards. Some patients <strong>with</strong><br />

have them. There are also historical accounts of what we<br />

would now call near-death experiences. They occur in<br />

different contexts, religions and eras. All of this suggests<br />

that the ability to have near-death experiences is a<br />

fundamental feature of Homo sapiens.<br />

How do people respond to these near-death<br />

experiences?<br />

The literature suggests that around 90 percent of neardeath<br />

experiences are viewed in very positive terms.<br />

Most people report a feeling of joy. Around 10 percent<br />

are negative, however, and interpreted as hellish, for<br />

example. Many people report meeting others who<br />

predeceased them, an experience they often portray<br />

104 DEATH JENS DREIER 105

as positive. Generally speaking, the return to this world,<br />

meaning survival, is experienced as painful and onerous.<br />

You can observe the brain activity of patients in<br />

the ICU. How do you do this – also during their<br />

near-death experiences? What processes do<br />

you use?<br />

We conduct neuromonitoring of patients <strong>with</strong> cerebral<br />

haemorrhages at the ICU. Those who passed away while<br />

we were recording the process of dying are no longer<br />

<strong>with</strong> us and cannot therefore be asked about their experiences.<br />

My clinical focus, however, is the stroke unit at<br />

the Charité campus in Berlin-Mitte. I do not systematically<br />

ask about near-death experiences, but sometimes the<br />

patients themselves talk about what they have experienced.<br />

Many of these accounts sound very convincing to<br />

me.<br />

How close to death were these people actually?<br />

The patients I’m thinking of were very close to death.<br />

When is a person dead?<br />

That’s not an easy question to answer … It also depends<br />

on factors like body temperature. For cardiac surgery<br />

or complicated aneurysm operations, bodies are often<br />

cooled down because that extends the period of time<br />

before processes of dying set in. Age plays a role as well.<br />

And resuscitation makes a big difference. After sudden<br />

cardiac arrest at a normal body temperature <strong>with</strong>out<br />

resuscitation, irreversible damage to the nerve cells will<br />

begin in about five minutes. The person will die after<br />

approximately 5 to 10 minutes.<br />

So there’s no precise definition of the time of<br />

death?<br />

No, it is hard to pinpoint the moment a cell dies even in<br />

an experimental setting. And it is even more complicated<br />

<strong>with</strong> a living mammal like Homo sapiens. How quickly<br />

one dies depends not only on factors specific to each<br />

individual, but also on external factors like ambient<br />

temperature. There is the famous case of the Norwegian<br />

physician Anna Bågenholm described in The Lancet<br />

medical journal. She went skiing <strong>with</strong> friends in a fjord<br />

region, fell head-first into a gully and was wedged above<br />

an underground stream. Her companions were unable<br />

to rescue her because the ground was so unstable. They<br />

called a helicopter, but when it arrived, she had been<br />

suspended amid ice and icy water for around 90 minutes<br />

and had no spontaneous circulation.<br />

The emergency team started cardio-pulmonary resuscitation<br />

(CPR) and airlifted her to a hospital, where<br />

cardiopulmonary bypass blood flow was restored around<br />

two hours later and where the lowest ever body temperature<br />

for a living human being – 13.7 degrees Celsius –<br />

was measured and documented. One year later, Anna<br />

Bågenholm had made a complete recovery, and she and<br />

her friends visited the site of the accident.<br />

In light of medical advances, end-of-life decisions<br />

are becoming ever more important in<br />

industrial countries. When is the time to end life<br />

support and switch off the machines?<br />

I think that can only be decided by talking <strong>with</strong> the<br />

individual people involved. It depends on the underlying<br />

illness and whether the patient’s condition can be<br />

treated in a reasonable way. There is no one-size-fits-all<br />

solution. At the ICU, doctors and nurses talk <strong>with</strong> family<br />

members and <strong>with</strong> patients if the latter are in a position<br />

to do so. The wishes that the patient has expressed in<br />

advance, or those that one assumes the patient would<br />

express if they were still able to give information, play a<br />

major role. Normally, it is a team decision as to whether<br />

further treatment is indicated. An important question in<br />

this process, of course, is whether a certain quality of<br />

life can be achieved. But that, too, is a difficult question,<br />

because how do you define quality of life? There have<br />

been studies of people <strong>with</strong> locked-in syndrome who<br />

were asked whether they wanted to live or die <strong>with</strong> their<br />

condition. The vast majority want to keep living and have<br />

accepted being in a state of nearly complete paralysis.<br />

As the name suggests, patients <strong>with</strong> this syndrome are<br />

essentially locked <strong>with</strong>in themselves, perhaps only able<br />

to move their eyes a little.<br />

You have watched many people die. Do you<br />

believe in the existence of an immortal essence<br />

or soul?<br />

As a scientist, I cannot answer this question. If asked for<br />

my personal opinion, I would say that if there is someone<br />

out there who thinks we should know, I would like to have<br />

A moment during an enormous wave<br />

(spreading depolarization)<br />

106 DEATH JENS DREIER 107

THE<br />

MORTUARY<br />

WHAT DOES<br />

HUMAN DIGNITY<br />

MEAN BEYOND<br />

DEATH?<br />

The corpse is not a neutral object. On the contrary, people<br />

all over the world have a desire to honour the deceased<br />

through rites of passage and burial. The way a society<br />

treats its deceased says something about its appreciation<br />

of every part of its community. Maintaining dignity is an<br />

elementary need not only in life, but also in death. What<br />

happens to the body after death? What does dignified care<br />

of a corpse mean?

LIV<strong>IN</strong>G WITH THE<br />

DEAD. LIV<strong>IN</strong>G WITH<br />

DEATH<br />

Liv Nilsson Stutz<br />

From the perspective of the Swedish bioarchaeologist<br />

Liv Nilsson Stutz, death triggers a double<br />

crisis for the bereaved: A part of social life is<br />

lost – and there is a dead body. Here, she addresses<br />

the universal significance of the ritual<br />

care of the corpse and its different cultural<br />

mani festations.<br />

MY MOTHER’S HANDS<br />

I sat next to my mother when she died. It was New Year’s<br />

Eve. I could hear a piercing distant sound of fireworks<br />

shooting through the air, lighting up the sky like ephemeral<br />

lost little comets. When I touched her hand, it was<br />

cold, soft and heavy in a way I had not felt before. Her<br />

face had been changed by sickness and death – the<br />

light was gone from her eyes and her features were<br />

sunken. But her hands were the same as the ones that<br />

held my hand as a child, combed my hair, kneaded the<br />

dough for the Sunday morning buns, knitted complicated<br />

patterns and left beautiful words in writing on casual<br />

notes and postcards and in diaries and letters. A ring my<br />

father had given to her when they were both young was<br />

on her finger and my siblings and I decided it would remain<br />

there when she was buried a few weeks later. When<br />

the funeral directors came to take her away the next<br />

day, I peeked into the room where she was resting and I<br />

was moved when I saw one of them respectfully adjust<br />

the sock on her foot before lifting her up to place her on<br />

the stretcher. They wheeled her out of her home to the<br />

hearse parked in the driveway in the cold January gloom<br />

and bowed in silence before closing the hatch. At that<br />

moment, I felt sadness, but also comfort. The respect<br />

they showed her reassured me that they would care for<br />

her and treat her <strong>with</strong> dignity until it was time for us to<br />

bury her. In that moment, it was clear that how we treat<br />

our dead matters because they are, despite it all, still<br />

people to us. I returned to the house to join my siblings,<br />

but it felt empty. She was no longer there.<br />

THE DUAL CRISIS OF DEATH<br />

<strong>Death</strong> is a universal human experience. We will all die,<br />

and before we do, most of us will experience the death<br />

of others close to us. But even if death is common and<br />

predictable, it is difficult. It tears us apart. It leaves a<br />

hole in our lives – where our social networks and relationships<br />

will need to be mended. For life to go on, responsibilities<br />

need to be reassigned, property redistributed<br />

and relationships reconfigured. This process often<br />

unfolds through a range of structured practices, some of<br />

which are regulated by law, and others that are private.<br />

But death is not only the loss of a social being. It also<br />

results in the emergence of a human cadaver – a dead<br />

body. This body needs to be cared for in a way that reassures<br />

the survivors. Beyond posing a practical problem<br />

to be solved, the dead body is potentially also problematic<br />

because after death, the natural processes of decay<br />

and decomposition will radically transform the body of<br />

our loved one to the point of becoming unrecognizable<br />

to us. This can be traumatic and human cultures have<br />

a range of different practices to deal <strong>with</strong> it. In some<br />

cultures, such as in the present-day United States, the<br />

natural processes are often controlled through complex<br />

techniques of embalming to replace the body fluids<br />

<strong>with</strong> chemicals in order to halt the decay. This practice<br />

became common during the Civil War, when the bodies<br />

of dead soldiers needed to be transported long distances<br />

for burial at home. Today, the tradition still holds<br />

a central place in the part of the culture that practices<br />

open-casket viewing during the memorial service. Embalming<br />

allows the mourners to see the body as if it were<br />

still alive and simply resting peacefully in the casket<br />

before final disposal. The practice of halting the natural<br />

decay of the body can be traced back to mummification<br />

in a range of societies around the world, from the Stone<br />

Age onward, <strong>with</strong> Egyptian mummies probably the most<br />

familiar in popular scientific knowledge and culture.<br />

Some cultures prefer to accelerate the process of<br />

decay, for example through cremation, which has been<br />

practiced by humans throughout our long prehistory<br />

and history. While it may appear to be a clean and quick<br />

process of immediate combustion, a closer look reveals<br />

that the burning of a human body requires an intense<br />

and practical engagement <strong>with</strong> the dead and often involves<br />

several steps in handling the cadaver, both during<br />

the burning itself and after the body has been reduced<br />

to burned bone fragments by the fire. The cremains are<br />

often picked over, burned bone is separated from the<br />

wood ash and charcoal and then redeposited. In our<br />

contemporary culture, the cremains are passed through<br />

a grinding mill to reduce them to a fine ash that can be<br />

scattered in the wind or transferred to an urn as a siltlike<br />

gray matter. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust.<br />

But, then again, not all cultures shy away from decay<br />

and decomposition. In fact, the natural processes of<br />

decomposition can be given a central place in the understanding<br />

of death as a process. In his seminal 1907<br />

essay on death, 1 Robert Hertz describes how the Dayak<br />

people in modern-day Indonesia conceive of the decomposition<br />

and putrefaction of the human body as a longer<br />

process that is a part of death itself, terminated only<br />

once the bones are clean and dry. The gradual decay<br />

gives form to the gradual transition to death and is thus<br />

embraced by the culture as meaningful. This practice<br />

is not unique and is found in many different cultures in<br />

Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Here, in a very<br />

tangible sense, the culture engages <strong>with</strong> death, not as an<br />

event but as a process that affects people and society in<br />

the longer term. The gradual transition to death can also<br />

take other forms. In Tana Toraja, on the Indonesian island<br />

of Sulawesi, the dead person is often kept in a coffin in<br />

the house until the family has saved up enough money<br />

to pay for the funeral. This can take up to a year, for the<br />

funeral is a costly affair involving the ritual slaughter of<br />

animals (in particular, buffalo). In addition to being a ritual<br />

of death, the funeral is also an arena for each family to<br />

display wealth and status in life. In the period leading up<br />

to the funeral, the deceased is not considered dead but<br />

merely “sick” or “asleep” – even hypervigilant – and the<br />

relationship <strong>with</strong> the living is maintained in tangible ways<br />

through symbolic offerings of food. <strong>Death</strong> thus remains<br />

embedded in life, entangled in sensory experiences and<br />

affect. 2 The natural processes of decomposition and<br />

putrefaction will, of course, begin to set in, and in order<br />

to control these processes, the family traditionally uses<br />

herbs and smoke – formalin being more commonly used<br />

today. The relationship <strong>with</strong> the dead continues even<br />

after the funeral. The dead are usually placed in collective<br />

burial sites that can be re-entered – both for the<br />

deposition of new dead and for visits <strong>with</strong> loved ones,<br />

which often involve gifts of food and drink. Outside the<br />

burial cave, effigies of the deceased take on a more<br />

lifelike shape of the people whose remains have been<br />

deposited inside, marking the cave as a resting place of<br />

ancestors.<br />

These few examples only scratch the surface of the<br />

diversity that we find in human responses to death<br />

around the world today. To cope <strong>with</strong> death, humans turn<br />

to ritual practices that enable us to make sense of death,<br />

find comfort and eventually move on in life. The ways<br />

in which different cultures handle this universal human<br />

experience vary greatly. The reason for this diversity<br />

is that in order to provide meaning and consolation, a<br />

ritual must fit into the overall cultural value system. It<br />

needs to make sense and be connected to other cultural<br />

values and concerns. What the various rituals all have in<br />

common, however, is that they simultaneously deal <strong>with</strong><br />

both the loss of a social being and the emergence of a<br />

cadaver.<br />

Why is it that the practical handling of the dead body<br />

tends to be so structured by cultural concerns? Why is it<br />

so meaningful? Why can we not just throw the corpse out<br />

<strong>with</strong> the trash? The mere suggestion makes us recoil –<br />

and it is somewhere in this reaction that we can begin to<br />

look for answers.<br />

112 THE MORTUARY LIV NILSSON STUTZ 113

CARE FOR THE<br />

DEAD<br />

The jewellery worn by a deceased person<br />

during his or her lifetime is gently removed<br />

from the body during the care of the corpse and<br />

presented to the surviving relatives in a pouch<br />

as a keepsake.<br />

The aim of mortuary care is to bring the<br />

corpse into a hygienic, aesthetic and dignified<br />

condition before burial. The person treating the<br />

corpse wears disposable gloves.<br />

What happens to the human body after death?<br />

A corpse is the object of care for the dead – from<br />

hygienic washing to the last garment and finally to<br />

burial. Beyond the hygienic care of the dead, thanatopractical<br />

treatment prepares the corpse for laying<br />

out. Selected utensils used in the care of the deceased<br />

are presented here.<br />

A comb is used to give the hair of the deceased<br />

an aesthetic form. A photo of the person before<br />

death is helpful when arranging the hairstyle.<br />

The jaw muscles of the corpse are loosened<br />

by means of massage. A transparent plastic<br />

support is concealed almost invisibly under the<br />

corpse’s graveclothes and holds the chin of the<br />

deceased in place.<br />

118 THE MORTUARY CARE FOR THE DEAD 119

A chin support is positioned under the jaw<br />

in such a way that the mouth remains closed<br />

during the laying out of the deceased.<br />

The sponge is used to cleanse the body of the<br />

deceased.<br />

Gauze dressing is used for wound treatment<br />

of the deceased. Open areas or wounds are<br />

bandaged.<br />

Cotton wool is used in mortuary care to both<br />

clean and close body orifices, such as the<br />

throat, nostrils or anus. This prevents body<br />

fluids from escaping.<br />

The large curved needle is used in thanatopractical<br />

care to close the mouth. The smaller,<br />

curved needles are used, among other things,<br />

to close wounds.<br />

Wet razors are gentler and more thorough than<br />

electric shavers. They are used to carefully<br />

shave the face of the deceased for the last time.<br />

The eyes are closed by using moisturizer to<br />

place contact lens-like eye caps <strong>with</strong> small nubs<br />

onto the eyeballs and pulling the eyelids over<br />

them. This prevents post-mortem drooping of<br />

the eyelids as well as possible reopening of the<br />

eyelids due to dehydration.<br />

Mouth shapers are used to correct the form of<br />

the mouth and to preserve the natural features<br />

of the face of the deceased. If necessary,<br />

sunken cheeks are filled in, and mouth formers<br />

can also replace dentures.<br />

120 THE MORTUARY CARE FOR THE DEAD 121

THE NAMES BEH<strong>IN</strong>D<br />

THE NUMBERS<br />

A wallet, a toothbrush, a picture of a saint, a mobile<br />

phone, and some soil from the homeland – personal<br />

things as the last evidence of a past life. The owners<br />

of these objects were victims of a ship disaster in the<br />

Mediterranean Sea on 18 April 2015, in which almost<br />

1,000 refugees drowned. In June 2016, Italy had the<br />

wreck lifted and ordered the identification of the deceased.<br />

The forensic anthropologist Cristina Cattaneo<br />

is still working <strong>with</strong> her team to identify the deceased.<br />

The personal belongings are relevant documents in<br />

their efforts to trace the identity of the dead. They can<br />

lead to a name, address or country and are also shown<br />

to people searching for missing relatives.<br />

136 THE MORTUARY THE NAMES BEH<strong>IN</strong>D THE NUMBERS 137

138 THE MORTUARY THE NAMES BEH<strong>IN</strong>D THE NUMBERS 139

CREDITS<br />

COLOPHON<br />

PHOTO CREDITS<br />

Cover: Getty Images/fergregory<br />

pp. 2–3: NASA/ESA/Antonella Nota (ESA,<br />

STScI), Hubble Heritage Project (STScI, AURA),<br />

Westerlund 2<br />

pp. 4–5: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Z. Levay<br />

pp. 6–7: NASA/JPL-Caltech<br />

pp. 8–9: NASA<br />

p. 31: Félix Ayoh’Omidire<br />

p. 33: Jan Zappe<br />

p. 35: picture alliance/NurPhoto/Morteza<br />

Nikoubazl<br />

p. 37: iStockphoto/Eillen<br />

p. 39: iStockphoto/Manaswi Patil<br />

p. 41: iStockphoto/NgKhanhVuKhoa<br />

p. 43: iStockphoto/EugeneTomeev<br />

p. 45: Atthapon Kulpakdeesingworn/Alamy<br />

Stock Photo<br />

p. 47: iStockphoto/texturis<br />

p. 49: iStockphoto/maogg<br />

p. 51: iStockphoto/Ale-ks<br />

p. 53: © Murray Ballard<br />

pp. 55–67: © Klaus Bo/deadandaliveproject.com<br />

pp. 76–98: Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner<br />

Schloss<br />

pp. 107, 109: © 2013, American Academy of<br />

Neurology<br />

pp. 119–121: Stiftung Humboldt Forum im<br />

Berliner Schloss, photo: Sebastian Eggler<br />

pp. 124–135: Infografiken: © Ole Häntzschel<br />

pp. 137–147: Mattia Balsamini/contrasto/laif<br />

p. 169: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN),<br />

inv. no. http://coll.mfn-berlin.de/u/93e2c4,<br />

photo: digitalisation team MfN<br />

p. 170 left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin<br />

(MfN), inv. no. ZMB_LEP_T 078_11,<br />

photo: digitalisation team MfN<br />

p. 170 right: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin<br />

(MfN), inv. no. http://coll.mfn-berlin.de/u/117d39,<br />

photo: digitalisation team MfN<br />

p. 171: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN),<br />

inv. no. http://coll.mfn-berlin.de/u/98cb42,<br />

photo: digitalisation team MfN<br />

p. 172 top left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Mam_47159, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 172 top right: © Museum für Naturkunde<br />

Berlin, inv. no. ZMB_Mam_5539,<br />

photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 172 bottom: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Mam_31624, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 173 top left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Mam_36877, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 173 top right: © Museum für Naturkunde<br />

Berlin, inv. no. ZMB_Mam_105471,<br />

photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 173 bottom left: © Museum für Naturkunde<br />

Berlin, inv. no. ZMB_Mam_16032,<br />

photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 173 bottom right: © Museum für Naturkunde<br />

Berlin, inv. no. ZMB_Mam_23707,<br />

photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 174: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, inv. no.<br />

ZMB_Crust_9979, photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 175: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, inv. no.<br />

ZMB_Moll_20892, photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 176 left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Mam_4622, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 176 right: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Mam_3568, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 177 left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Herp_29895,<br />

photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 177 right: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Herp_30755, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 178 left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, inv.<br />

no. ZMB_Herp_2131, photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 178 right: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Herp_8948, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

p. 179 left: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, inv.<br />

no. ZMB_Pisces_3933, photo: Johannes Kramer<br />

p. 179 right: © Museum für Naturkunde Berlin,<br />

inv. no. ZMB_Pisces_33225, photo: Johannes<br />

Kramer<br />

pp. 192–199: © Manfred P. Kage - Kage GbR<br />

TEXT RIGHTS<br />

pp. 180–183: Unaltered reprint of the essay<br />

“People of Corn, People of Light”, in Robin Wall<br />

Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous<br />

Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the<br />

Teachings of Plants. Copyright © 2013, 2015<br />

by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Reprinted <strong>with</strong> the<br />

permission of The Permissions Company, LLC<br />

on behalf of Milkweed Editions, ww.milkweed.<br />

org<br />

Published by the Stiftung Humboldt Forum im<br />

Berliner Schloss<br />

This book has been published to accompany<br />

the exhibition in_finite. <strong>Living</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Death</strong> at the<br />

Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 31 March – 26 November<br />

2023<br />

An exhibition by the Stiftung Humboldt Forum<br />

im Berliner Schloss (SHF)<br />

General Director Humboldt Forum<br />

Hartmut Dorgerloh<br />

Curatorial Team Exhibition<br />

Detlef Vögeli – Lead Curator<br />

Gesine Last, Jan Zappe – Co-Curators<br />

Kathrin Haase, Lydia Heller, Yvonne Zindel –<br />

Curatorial collaboration and research<br />

Sibylle Kußmaul, Marc Wrasse – Curators of<br />

Education and Outreach, SHF<br />

Project Team Exhibition SHF<br />

David Blankenstein – Project management<br />

Frank Meißner – Project assistance<br />

Maria Mazgaj – Technical project management,<br />

SHF<br />

Noelle von Galen, Bryn Veditz – Registrars, SHF<br />

Johanna Kapp, Maike Voelkel – Conservation, SHF<br />

Isabel Meixner, Sarah Lindemann, Franziska<br />

Lukas – Project collaboration<br />

Head of Exhibitions, SHF<br />

Anke Daemgen<br />

Exhibition Design<br />

Tom Piper/Alan Farlie<br />

Exhibition Graphics<br />

BOK+ Gärtner GmbH<br />

Lenders<br />

Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin<br />

Grieneisen Bestattungen, Berlin<br />

Bestatter-Innung von Berlin und Brandenburg<br />

KdöR/Bestatter-Verband von Berlin und<br />

Brandenburg e.V.<br />

European Biostasis Foundation<br />

Publication Project Management<br />

Susanne Müller-Wolff, SHF<br />

Concept<br />

Detlef Vögeli, Jan Zappe<br />

Copy Editing<br />

Danko Szabó<br />

Picture Editing<br />

Barbara Martinkat, SHF<br />

Translations from the German into English<br />

Gérard Goodrow, Bram Opstelten, Marlene<br />

Schoofs<br />

Interviews, recordings and translations:<br />

Contemporary Notions of the Hereafter<br />

Yıldız Aslandoğan, Lydia Heller, Gesine Last,<br />

Manvir Kaur Mahidwan, Cora Säbel, Detlef<br />

Vögeli, Antje Zemmin, Yvonne Zindel<br />

Interviews, recordings and translations:<br />

World <strong>Death</strong> Conference<br />

Menny Aviv, Kathrin Haase, Manvir Kaur<br />

Mahidwan, Thuy-Trang Nguyen Ngoc, Takin<br />

Yasar, Antje Zemmin<br />

Layout, typesetting and cover design<br />

Sahar Aharoni<br />

Typefaces<br />

ABC Oracle, SangBleu Versailles, Star Pro<br />

Paper<br />

Arctic Silk<br />

Cover Illustration<br />

Candy skull for “Day of the Dead” in Mexico<br />

The Stiftung Humboldt Forum sincerely thanks<br />

the authors, the interview partners and the<br />

lenders. We would like to thank the staff of the<br />

Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss as<br />

well as all those not mentioned here by name who<br />

have contributed to the success of this project.<br />

© 2023 Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner<br />

Schloss, Schloßplatz, 10178 Berlin, and E. A.<br />

Seemann Verlag <strong>with</strong>in the E. A. Seemann<br />

Henschel GmbH & Co. KG, Leipzig<br />

ww.seemann-henschel.de<br />

ww.humboldtforum.org<br />

Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner<br />

for Culture and the Media in keeping <strong>with</strong><br />

a resolution by the German Federal Parliament.<br />

External links contained in the text could be<br />

reviewed only up to the publication date. The<br />

issuer and publisher have had no influence<br />

on later changes and can therefore accept no<br />

liability.<br />

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this<br />

publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie;<br />

detailed bibliographic data is available on the<br />

Internet at ww.dnb.de.<br />

Publishing<br />

E.A. Seemann Verlag<br />

Project Management Publishing house<br />

Caroline Keller<br />

Image Processing<br />

Bild1Druck GmbH, Berlin<br />

Printing and Binding<br />

feingedruckt – Print und Medien, Neumünster<br />

All rights reserved<br />

ISBN 987-3-86502-507-4<br />

188 CREDITS COLOPHON 189