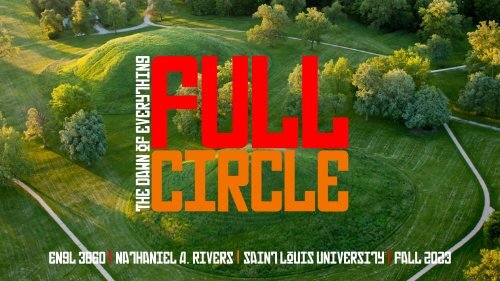

ENGL 3860: Full Circle

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The dawn of everything<br />

<strong>Full</strong><br />

<strong>Circle</strong><br />

<strong>ENGL</strong> <strong>3860</strong> | Nathaniel A. Rivers | saint Louis university | fall 2023

Portraying history as a story of material progress, that framework<br />

recast indigenous critics as innocent children of nature, whose<br />

views on freedom were a mere side effect of their uncultivated<br />

way of life and could not possibly offer a serious challenge to<br />

contemporary social thought (which came increasingly to mean just<br />

European thought).<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 441

What evolution does not look like.

What evolution might look like.

Blinded by the ‘just so’ story of how human societies evolved, they<br />

can’t even see half of what’s now before their eyes. <br />

As a result, the same portrayers of world history who profess<br />

themselves believers in freedom, democracy and women’s rights<br />

continue to treat historical epochs of relative freedom, democracy<br />

and women’s rights as so many ‘dark ages’. Similarly, as we’ve<br />

seen, the concept of ‘civilization’ is still largely reserved for societies<br />

whose defining characteristics include high-handed autocrats,<br />

imperial conquests and the use of slave labour.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 442

The reason why these ways of thinking remain in place, no<br />

matter how many times people point out their<br />

incoherence, is precisely because we find it so difficult to<br />

imagine history that isn’t teleological—that is, to<br />

organize history in a way which does not imply that<br />

current arrangements were somehow inevitable.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 449

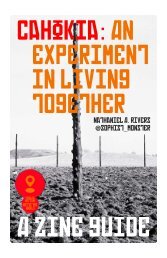

Cahokia’s population peaked at something in the order of 15,000<br />

people; then it abruptly dissolved. Whatever Cahokia represented in<br />

the eyes of those under its sway, it seems to have ended up being<br />

overwhelmingly and resoundingly rejected by the vast majority of<br />

its people. For centuries after its demise the site where the city once<br />

stood, and hundreds of miles of river valleys around it, lay entirely<br />

devoid of human habitation<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 450

[W]hat we can say with some confidence is that the societies<br />

encountered by European invaders from the sixteenth<br />

century onwards were the product of centuries of political<br />

conflict and self-conscious debate. They were, in many cases,<br />

societies in which the ability to engage in self-conscious<br />

political debate was itself considered one of the highest human<br />

values.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 450

In Cahokia and its hinterland we can chart the<br />

rise of social hierarchies through the lens of<br />

chunkey, as the game became increasingly<br />

monopolized by an exclusive elite. One sign<br />

of this is how stone chunkey discs disappear<br />

from ordinary burials, just as beautifully crafted<br />

versions of them start to appear in the richest<br />

graves. Chunkey was becoming a spectator<br />

sport, and Cahokia the sponsor of a new<br />

Illinois State Museum<br />

regional, Mississippian elite.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 465

Whatever happened in<br />

Cahokia, it appears to<br />

have left extremely<br />

The “Vacant Quarter,” Circa 1450<br />

unpleasant memories.<br />

The Vacant Quarter<br />

implies a self-conscious<br />

rejection of everything<br />

the city of Cahokia stood<br />

for.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 468-69

What we would now call social movements often<br />

took the form of quite literal physical movements.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 469

[T]he Osage, who ascribed key roles to sacred<br />

knowledge in their political affairs, in no sense saw<br />

their social structure as something given from on high<br />

but rather as a series of legal and intellectual<br />

discoveries—even breakthroughs.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 480

What [t]his example demonstrates, we suggest, is that even within<br />

indigenous society, the political question was never definitively<br />

settled. Certainly, the overall direction, in the wake of Cahokia, was<br />

a broad movement away from overlords of any sort and towards<br />

constitutional structures carefully worked out to distribute power in<br />

such a way that they would never return. But the possibility that<br />

they might always lurked in the background. Other paradigms of<br />

governance existed, and ambitious men—or women—could, if<br />

occasion allowed, appeal to them.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 491

In other words, not only did indigenous North Americans<br />

manage almost entirely to sidestep the evolutionary trap that<br />

we assume must always lead, eventually, from agriculture to<br />

the rise of some all-powerful state or empire; but in doing so<br />

they developed political sensibilities that were ultimately to<br />

have a deep influence on Enlightenment thinkers and,<br />

through them, are still with us today.<br />

Graeber and Wengrow | The Dawn of Everything | 492