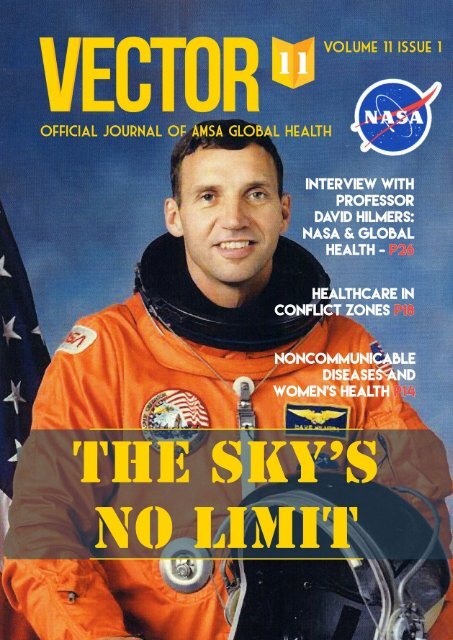

Vector Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1

Advisory Board<br />

The Advisory Board, established in <strong>2017</strong>, consists of academic mentors who provide guidance for the<br />

present and future direction of <strong>Vector</strong>.<br />

Dr Claudia Turner<br />

Consultant paediatrician and clinician scientist with the University of Oxford & Chief Executive Officer of<br />

Angkor Hospital for Children.<br />

Professor David Hilmers<br />

Professor in the Departments of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, the Center for Global Initiatives, and<br />

the Center for Space Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine<br />

Associate Professor Nicodemus Tedla<br />

Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales School of Medical Sciences<br />

Dr Nick Walsh<br />

Medical Doctor (RACP) & Regional Advisor for Viral Hepatitis at the Pan American Health Organization<br />

/ World Health Organization Regional Office for the Americas<br />

<strong>2017</strong> <strong>Vector</strong> Committee<br />

Editor-in-chief<br />

Carrie Lee carrie.lee@amsa.org.au<br />

Associate Editors<br />

Kryollos Hanna Sophie Lim Koshy Matthew Nic Mattock Aidan Tan<br />

Ash Wilson-Smith Sophie Worsfold Danica Xie<br />

Publication Designer<br />

Lucy Yang<br />

Design and layout<br />

© <strong>2017</strong>, <strong>Vector</strong><br />

Australian Medical Students’ Association Ltd, 42 Macquarie Street, Barton ACT 2600<br />

vector@globalhealth.amsa.org.au<br />

vector.amsa.org.au<br />

Content<br />

© <strong>2017</strong>, The Authors<br />

Cover designs by Lucy Yang (University of New South Wales)<br />

<strong>Vector</strong> Journal is the official student-run journal of AMSA Global Health.<br />

Responsibility for article content rests with the respective authors. Any views contained within articles are those of the<br />

authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the <strong>Vector</strong> Journal or the Australian Medical Students’ Association.<br />

i

Contents<br />

Editor’s Note: The Sky’s No Limit 1<br />

Commentary<br />

Rise of Trump/Fall of Health 2<br />

Owen Burton<br />

Anti-vaccination: Separating Fact from Fiction 5<br />

Elissa Zhang<br />

Climate Change and <strong>Vector</strong>-Borne Disease in Kiribati 8<br />

Erica Longhurst<br />

Features<br />

Humanity Lost? <strong>11</strong><br />

Patrick Walker<br />

Redefining Women’s Health: A Noncommunicable Diseases Perspective 14<br />

Charlotte O’Leary<br />

Healthcare in Conflict Zones 18<br />

Michael Wu<br />

Surgery: Luxury or Necessity? 22<br />

Maryam Ali Khan (Pakistan), Zineb Bentounsi (Morocco), Nayan Bhindi (Australia), Helena Franco (Australia), Tebian<br />

Hassanein Ahmed Ali (Sudan), Katayoun Seyedmadani (Grenada/USA), Ruby Vassar (Grenada), Dominique Vervoort<br />

(Belgium)<br />

Beyond the Horizon and Back Again: Interview with Professor David Hilmers 26<br />

Ashley Wilson-Smith<br />

Reviews<br />

PrEP-related health promotion for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Gay and Bisexual Men 29<br />

Alec Hope<br />

Mental Illness Following Disasters in Low Income Countries 32<br />

Rose Brazilek<br />

Factors that Contribute to the Reduced Rates of Cervical Cancer Screening in<br />

Australian Migrant Women - a Literature Review 36<br />

Archana Nagendiram<br />

Medical Electives in Resource-poor Settings: Are We Doing More Harm Than Good? 40<br />

Gabrielle Georgiou<br />

Conference reports<br />

IFMSA - 5 letters with one big mission! Australian Medical Students attend the IFMSA 66th<br />

General Assembly in Montenegro 44<br />

Aysha Abu-sharifa, Stormie de Groot, Julie Graham, Justine Thomson<br />

Changing Climate, Changing Perspectives: iDEA Conference Report 47<br />

Isobelle Woodruff<br />

ii

Editor’s Note: The Sky’s No Limit<br />

Of the many things that come to mind when one thinks<br />

about global health, an astronaut is probably not high on the<br />

list. The front cover of this first issue of <strong>Vector</strong> for <strong>2017</strong> is<br />

not what we would conventionally expect of a global health<br />

journal. And yet, that is precisely the message that this issue<br />

conveys – the limitless diversity that global health has come<br />

to represent. We are living in an increasingly globalised world,<br />

with greater wealth and inequality we have ever encountered.<br />

We have made remarkable progress over the past few<br />

decades on the frontier of global health, including increased<br />

vaccination and access to treatment for diseases such as<br />

HIV. However, the agenda is now shifting to focus on new and<br />

emerging challenges.<br />

Undoubtedly, healthcare in a global context is intrinsically<br />

connected to the political, social and cultural phenomena<br />

that define today’s world. The rise to power of the United<br />

States President Donald Trump raises serious questions<br />

and concerns about the future of global health, with his<br />

controversial approaches and perspectives towards climate<br />

change, refugees and migrants, as well as sexual and<br />

reproductive health. Owen Burton (p 2) provides a thoughtprovoking<br />

commentary on these issues, and urges Australia<br />

to consider our future potential role in leading an alternative<br />

direction rather than following the direction set by the US.<br />

War and conflict, political stability and human rights<br />

also intersect with global health issues, as we see with the<br />

distressing increase in targeted attacks on health care<br />

facilities, Michael Wu (p 18) offers an insightful perspective<br />

into the situation of medical neutrality in conflict zones. In<br />

addition to man-made crises, natural disasters also pose a<br />

threat to human health and health care systems, with mental<br />

health implications a particular concern deserving attention,<br />

as discussed by Rose Brazilek (p 32).<br />

Climate change is the greatest challenge we are facing<br />

in the global health arena. Personal experiences and<br />

commentary are provided by Erica Longhurst (p 8).<br />

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) account for a<br />

substantial proportion of the global burden of disease. We<br />

are reminded by Charlotte O’Leary (p 14) that we need<br />

to question and redefine the approach we take towards<br />

this issue, to ensure that women’s health is not limited to<br />

reproductive health concerns, but a holistic approach over<br />

the entire life course, including addressing the risk factors<br />

and burden of NCDs specific to women and girls.<br />

Yet whilst our focus often turns to issues “abroad”, there<br />

is much to be addressed in global health on a local level.<br />

Health promotion amongst key populations in Australia is a<br />

particular topic of interest. A comprehensive review article by<br />

Alec Hope (p 29) describes issues regarding the promotion<br />

of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis amongst Aboriginal gay and<br />

bisexual men in Australia. Migrant women in Australia also<br />

have lower rates of cervical cancer screening; the factors<br />

and interventions to address this issue are explored in a<br />

review article by Archana Nargendiram (p 36).<br />

The recent health policy “No Jab No Play / No Jab No<br />

Pay” also raises the issue of vaccination scepticism and<br />

conscientious objection, a concerning phenomenon in<br />

Australia as well as worldwide. A commentary by Elissa<br />

Zhang (p 5) provides an interesting overview of historical<br />

events like the Cutter Incident (involving the polio vaccine)<br />

and common concerns held by ‘anti-vaxxers’.<br />

With so much happening in global health, it is<br />

understandable for the general public, and particularly young<br />

people, to feel disenfranchised or disempowered. We even<br />

become desensitised and apathetic to the problems; such as<br />

conflict, mass displacement and natural disasters; that we<br />

are constantly exposed to in the media. Patrick Walker calls<br />

on us to remember the human side to the tragedies that we<br />

see, but also to promote tolerance and understanding with<br />

people who hold different views to our own (p <strong>11</strong>).<br />

An interview by Ashley Wilson-Smith with NASA astronaut,<br />

paediatrician and internist Professor David Hilmers (p 26)<br />

provides a window into his vast experiences in resourcepoor<br />

settings, including recently in the Ebola crisis, and the<br />

interview reinforces that global health is not always what we<br />

expect it to be. Professor Hilmers is also one of our Advisory<br />

Board members, a new initiative aimed at strengthening the<br />

academic standard and longevity of <strong>Vector</strong> Journal.<br />

There is a growing community of medical students who<br />

share a passion for global health. (Indeed, they are attending<br />

conferences around the world, including at Doctors for the<br />

Environment Australia (Belle Woody, p47) and with the IFMSA<br />

in Montenegro (p44)!) Unlike other medical specialities that<br />

have a clear career pathway, global health is a blank canvass.<br />

It is hard to define, and that lends a huge amount of potential<br />

– global health can be anything that you want it to be. There<br />

is “no limit” in that sense!<br />

I believe that the contents of this issue speak to the<br />

diversity of global health. Not only does it bring attention<br />

to some of the greatest challenges, it also celebrates the<br />

developments in research, collaboration and policies that<br />

pave the way towards new and creative solutions. We hope<br />

this issue engages you, inspires you, and challenges your<br />

ideas and assumptions about global health. I am incredibly<br />

grateful to the <strong>Vector</strong> Committee, to all of our authors and<br />

contributors, to the Advisory Board, AMSA Global Health and<br />

many other supporters.<br />

Dear Reader, let <strong>Vector</strong> be a platform for you to launch<br />

beyond the horizon into global health.<br />

Carrie Lee, <strong>Vector</strong> Editor-in-Chief <strong>2017</strong><br />

Correspondance: carie.lee@amsa.org.au<br />

1

Rise of Trump/Fall of Health<br />

[Commentary]<br />

Owen Burton<br />

Owen Burton holds degrees of Bachelor of Biomedical Science (Griffith University)<br />

and Masters of Orthoptics (University of Technology, Sydney)<br />

As Donald Trump took the stage declaring<br />

victory as the 45th President of the United<br />

States and the Leader of the Free World, I had<br />

a sudden chilling realisation. This man, who<br />

has spent his entire life ignoring or actively<br />

working against the dangers of climate change,<br />

progressive social policy and a centralised<br />

state control healthcare system, now sits at<br />

the head of the American government, which<br />

sets the trends in policy and action in the<br />

Western world.<br />

His often-repeated goal during campaigning<br />

was to “repeal and replace” Obamacare by<br />

relaxing legislation which prevents exploitation<br />

of the injured by private<br />

insurance interests, and<br />

removing funding for vital<br />

infrastructure in hospitals and<br />

speciality clinics, as well as<br />

sexual health and Planned<br />

Parenthood programmes.<br />

Although he has, so far, been<br />

unsuccessful in repealing<br />

Obamacare, he has not given up his crusade<br />

against basic healthcare provisions.<br />

Under Trump’s direct guidance, Tom Price,<br />

head of the Department of Health and Human<br />

Resources, continues to reduce requirements<br />

for insurance companies to provide essential<br />

benefits, and works towards completely<br />

dismantling systems related to women’s or<br />

sexual health. Such a removal of support and<br />

shift away from women is concerning, as it<br />

appears to indicate the return of deep-seated<br />

sexism within governmental institutions which<br />

sets an example for the wider society.<br />

These cuts will jeopardise the health<br />

of the world’s most at-risk individuals<br />

by removing access to education<br />

and preventative measures against<br />

sexually transmitted diseases, as well<br />

as all facets of maternal healthcare.<br />

While Trump has proven time and time<br />

again that he has little regard for females, this<br />

blatant attack seems like an extreme first step.<br />

People have been protesting the numerous<br />

unconstitutional and unethical executive<br />

orders streaming from the desk of the White<br />

House through large organised protests, rallies<br />

at offices of local governmental officials<br />

and online petitions. It is vital, however, that<br />

this momentum does not weaken: accepting<br />

this situation as the new ‘normal’ cannot be<br />

allowed to happen. Having to fight constantly<br />

is exhausting but essential. Without significant<br />

resistance, it is likely that Trump will be able<br />

push many of these bills through a Republicandominated<br />

congress and into<br />

law.<br />

Trump’s executive order to<br />

freeze funding and support for<br />

global aid serves to reinstate<br />

and expand Reagan’s 1984<br />

ban on United States (US)<br />

foreign aid. All $9.5 billion<br />

USD of American global health funding will<br />

be restricted from being available to any nongovernment<br />

organisations providing or even<br />

discussing abortion with patients.[1, 2] These<br />

cuts will jeopardise the health of the world’s<br />

most at-risk individuals by removing access to<br />

education and preventative measures against<br />

sexually transmitted diseases, as well as all<br />

facets of maternal healthcare. The World<br />

Health Organization estimated that a total of<br />

225 million women in developing countries<br />

were not using contraception, mainly due to<br />

lack of access and education.[3] With the<br />

implementation of this gag, it is expected that<br />

these numbers will rise significantly.<br />

2

Trump has made it clear that he is committed<br />

to the promises he made going into the<br />

election – promises which have the potential to<br />

jeopardise global health. The next step is likely<br />

to be severe cuts or the removal of foreign aid<br />

funding entirely, as Trump has expressed on<br />

Slashing America’s global aid<br />

support will only result in detriment for<br />

those people already suffering from<br />

the consequences of poor support<br />

for health services; a rise in disease,<br />

poverty and death are to be expected<br />

if this policy is to be implemented.<br />

multiple occasions that he has no intention of<br />

being “president to the world”. By internalising<br />

focus, Trump aims to disconnect America from<br />

the rest of the world – a process that has<br />

started with reduction and removal of aid and<br />

is predicted to continue with taxing of overseas<br />

goods.<br />

The impact this will have on global health<br />

programs is not to be underestimated. Slashing<br />

America’s global aid support will only result in<br />

detriment for those people already suffering<br />

from the consequences of poor support for<br />

health services; a rise in disease, poverty and<br />

death are to be expected if this policy is to be<br />

implemented.<br />

and taking a strong stand on healthcare and<br />

foreign aid, Australia could become a rally point<br />

for other nations – a model for them to work by<br />

and therefore improve the lives of millions of<br />

people who have already, and will be, affected<br />

by the rise of Trump.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

None<br />

Conflict of Interest<br />

None declared<br />

Correspondence<br />

oburton101@gmail.com<br />

References<br />

1. Filipovic J. The Global Gag Rule: America’s Deadly<br />

Export. Foreign Policy. <strong>2017</strong> March; 20.<br />

2. Office of the Press Secretary, White House.<br />

White House. [Online].; <strong>2017</strong> [cited <strong>2017</strong> May 10.<br />

Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/<strong>2017</strong>/01/23/presidential-memorandum-regardingmexico-city-policy.<br />

3. Singh S, Darroch J, Ashford L. Adding It Up:<br />

The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Sexual and<br />

Reproductive Health 2014. Guttmacher Institute; 2014.<br />

Australia has an opportunity, and a<br />

responsibility here to intervene. As a country<br />

with the wealth and resources to help, we would<br />

be passively condoning Trump’s gag policy if<br />

we do not aim to lessen its blow on developing<br />

nations. By increasing our international aid<br />

and presence, as well as encouraging other<br />

countries to do so, we can hopefully avoid the<br />

rise of neoliberalist nationalism we have seen<br />

in America, and help prevent its consequences<br />

to global health.<br />

Most importantly, Australia needs to stand<br />

up against America on this issue. It is time for<br />

Australia to take the lead. By changing direction<br />

3

4

Anti-vaccination: Separating Fact<br />

from Fiction<br />

[Commentary]<br />

Elissa Zhang<br />

Elissa is a 4th year medical student at UNSW. She currently conducts research<br />

on parental attitudes towards vaccine policies and media portrayals of vaccine<br />

safety at the UNSW School of Public Health and Community Medicine.<br />

Vaccines are indubitably one of the great<br />

successes of public health, on par with clean<br />

water and basic sanitation. They have saved<br />

millions of lives, and even eradicated infectious<br />

diseases such as smallpox.[1]<br />

Yet, regardless of these achievements, the<br />

legitimacy and safety of vaccinations are still<br />

questioned. Earlier this year Australian One<br />

Nation Senator Pauline Hanson urged parents to<br />

take a non-existent “vaccine-reaction test”,[2]<br />

and United States (US) President Donald Trump<br />

called for a commission into vaccine safety.<br />

[3] Furthermore, the recent implementation<br />

of stricter childhood vaccination policies (No<br />

Reasons behind vaccination hesitancy<br />

For as long as vaccines have been around,<br />

there have been those who oppose them.<br />

Vaccine opposition began in early 1800s in<br />

Europe with the first vaccination mandates.<br />

Scientists, doctors, and members of the public<br />

questioned the scientific basis of vaccines,<br />

even citing that they would disturb with God’s<br />

“natural control over the balance between<br />

the blessed and the damned”.[5] The modern<br />

manifestation of vaccine objection is<br />

simply another iteration of this longstanding<br />

phenomenon..<br />

Jab No Pay; No Jab No Play) in Australia has<br />

raised contentious ethical issues regarding<br />

consent and balancing medical paternalism<br />

and parental autonomy in the provision of<br />

healthcare to children.[4]<br />

Ironically, the great success of vaccinations<br />

in dramatically reducing, and even eradicating<br />

disease is contributing to their own downfall.<br />

As diseases like measles and polio are no<br />

longer endemic in Australia, parents no longer<br />

directly face the harms of these highly virulent<br />

and contagious diseases. Consequently, they<br />

5

may perceive the risks from vaccinations to be<br />

greater than the likelihood of contracting the<br />

very diseases they prevent.[5]<br />

In fact, surveys of Australian parents show<br />

that the primary reason for vaccine hesitancy<br />

or objection is concerns about their safety[6]<br />

and a third of parents believe children are<br />

over-vaccinated. Newer vaccines, like the<br />

HPV vaccine, can be perceived to have<br />

a lower risk-benefit ratio, as they protect<br />

against diseases that are less prevalent or<br />

virulent. Older vaccines also face doubts, as<br />

the diseases they prevent are less common<br />

or even eliminated in the Australia, such as<br />

measles. Furthermore, concerns about adverse<br />

reactions to vaccination are growing. This could<br />

be attributed to the fact that such reactions<br />

are perceived to be more common than the<br />

diseases that they prevent.<br />

Common misconceptions regarding vaccines<br />

Rare but severe adverse reactions to<br />

some vaccinations attract great public<br />

interest, and give rise to misconceptions or<br />

over-estimations regarding their harms. For<br />

instance, the 1955 Cutter Incident in the USA<br />

involved administration of 380,000 doses of<br />

incompletely inactivated polio vaccinations to<br />

healthy children, which resulted in 40,000 cases<br />

of abortive polio (a minor form that does not<br />

involve the central nervous system), 51 cases<br />

of permanent paralysis and five deaths. It also<br />

started a polio epidemic, leaving even more<br />

people in the community affected.[7]<br />

This event severely undermined public<br />

confidence in the safety of vaccinations, even<br />

after it prompted the instigation much safer<br />

and stricter regulation of vaccines.[7] Incidents<br />

such as this undermine trust in vaccine safety,<br />

and these fears must be addressed in the<br />

community.<br />

Commonly, anti-vaxxers also claim that while<br />

they are not against vaccinations themselves,<br />

they oppose the adjuvants and preservatives<br />

that are potentially harmful, like thiomersal.<br />

However, studies have not been able to identify<br />

any harmful effects related to thiomersal, and<br />

even so, it was removed from all Australian<br />

childhood vaccines.[8]<br />

One of the most infamous controversies<br />

surrounding vaccine safety was Andrew<br />

Wakefield’s retracted 1998 paper that linked<br />

the Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR)<br />

vaccine to autism and bowel disease. His study<br />

was severely flawed, involving a sample of only<br />

12 children, and Wakefield was deregistered<br />

and discredited. In comparison, a Danish<br />

retrospective cohort study investigated over<br />

500,000 children who received the MMR vaccine<br />

and proved that there was no association<br />

between the vaccine and autism.[9] Despite<br />

this, many of the general public still believe in<br />

the association between the MMR vaccine and<br />

autism as a consequence of Wakefield’s study.<br />

Vaccine objection in the context of Australian<br />

vaccination policies<br />

As of January 2016, the nationwide legislation<br />

called “No Jab No Pay” has been put into<br />

effect, removing conscientious objection from<br />

exemption criteria to immunisation requirements<br />

for Centrelink childcare payments worth up to<br />

$19,000. A press release by then Prime Minister<br />

Tony Abbott and Health Minister Scott Morrison<br />

stated that “the choice made by families not<br />

to immunise their children is not supported by<br />

public policy or medical research nor should<br />

such action be supported by taxpayers in the<br />

form of child care payments”.[10]<br />

In contrast, public health experts believe that<br />

this policy is may be misplaced in its aims to<br />

reduce conscientious objection to vaccination,<br />

rather than addressing the more prominent<br />

barriers of access to services, logistical<br />

issues, and missed vaccination opportunities.<br />

[<strong>11</strong>] A policy such as this could also threaten<br />

the validity of a patient’s informed consent,<br />

which is outlined in the Australian Immunisation<br />

Handbook as being “given voluntarily in the<br />

absence of undue pressure, coercion or<br />

manipulation”.[12] This has generated a fresh<br />

6

debate into the ethics of mandating vaccines<br />

through paternalistic policy.<br />

Conflict of Interest<br />

None declared<br />

Statistics released in July 2016 show that<br />

following the implementation of this policy,<br />

148,000 incompletely vaccinated children had<br />

caught up, including 5,738 children of parents<br />

with previous conscientious objections.[13]<br />

Implications as medical professionals<br />

Public attitudes towards<br />

vaccinations are complex, as<br />

they are affected by a wide<br />

range of sources, including the<br />

media, personal experiences,<br />

and health providers. A<br />

variety of strategies should<br />

be implemented to influence<br />

such attitudes. For instance,<br />

willingness to vaccinate could<br />

be encouraged by focusing on improving<br />

awareness of the risks of vaccine preventable<br />

diseases, rather than discrediting or refuting<br />

myths about vaccine dangers. An intervention<br />

based on this strategy showed that higher risk<br />

perception of diseases resulted in an increased<br />

willingness to vaccinate.[14] It was also shown<br />

that rates of conscientious objection were<br />

reduced in areas with more administrative<br />

barriers to obtaining one.<br />

As future health professionals, we need<br />

to develop skills to practise evidence-based<br />

medicine. We need to be able to formulate our<br />

opinions based on verified facts, before helping<br />

parents to make informed decisions about<br />

vaccinations. We too can also be influenced by<br />

the vast amount of facts and misinformation<br />

disseminated about vaccinations in the media.<br />

Thus, it is our responsibility to stay up-to-date<br />

with the latest literature and separate fact from<br />

fiction, in order to provide the best care for our<br />

patients.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Supervisor Prof. Raina MacIntyre, UNSW<br />

r.macintyre@unsw.edu.au<br />

Correspondence<br />

elissa.j.zhang@gmail.com<br />

References<br />

As of January 2016, the<br />

nationwide legislation called “No<br />

Jab No Pay” has been put into<br />

effect, removing conscientious<br />

objection from exemption criteria<br />

to immunisation requirements for<br />

Centrelink childcare payments<br />

worth up to $19,000.<br />

1. Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to<br />

global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans<br />

R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1645):20130433.<br />

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/<br />

articles/PMC4024226/ DOI: 10.1098/<br />

rstb.2013.0433<br />

2. Australian Broadcasting<br />

Corporation. Pauline Hanson joins<br />

Insiders [Internet]. Sydney NSW:<br />

Australian Broadcasting Corporation;<br />

<strong>2017</strong> [cited <strong>2017</strong> May 29]. Available<br />

from: http://www.abc.net.au/insiders/<br />

content/2016/s4630647.htm<br />

3. Wadman M. Robert F. Kenndey Jr.<br />

says a ‘vaccine safety’ commission<br />

is still in the works. Science [Internet].<br />

<strong>2017</strong> Feb [cited <strong>2017</strong> May 29]. Available from: http://<br />

www.sciencemag.org/news/<strong>2017</strong>/02/robert-f-kennedy-jrsays-vaccine-safety-commission-still-works<br />

4. National Centre for Immunisation Research &<br />

Surveillance [Internet]. Westmead NSW: NCIRS; 2016. No<br />

jab no play, no jab no pay policies; 2016 [cited <strong>2017</strong> May<br />

29]; [all screens]. Available from: http://www.ncirs.edu.<br />

au/consumer-resources/no-jab-no-play-no-jab-no-paypolicies/<br />

5. Bond L, Nolan T. Making sense of perceptions of<br />

risk of diseases and vaccinations: a qualitative study<br />

combining models of health beliefs, decision-making and<br />

risk perception. BMC Public Health. 20<strong>11</strong>;<strong>11</strong>:943.<br />

6. Rhodes A. Vaccination: perspectives of Australian<br />

parents [Internet]. Melbourne VIC: The Royal Children’s<br />

Hospital Melbourne; <strong>2017</strong> [cited <strong>2017</strong> May 29]. 6 p.<br />

Available from: https://www.childhealthpoll.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/2015/10/ACHP-Poll6_Detailed-report_<br />

FINAL.pdf<br />

7. Offit PA. The Cutter incident, 50 years later. N Engl J<br />

Med. 2005;352(14):14<strong>11</strong>-2.<br />

8. National Centre for Immunisation Research &<br />

Surveillance. Thiomersal FactSheet [Internet]. Westmead<br />

NSW: NCIRS; 2009 [cited <strong>2017</strong> May 29]. 5 p. Available<br />

from: http://www.ncirs.edu.au/assets/provider_resources/<br />

fact-sheets/thiomersal-fact-sheet.pdf<br />

9. Madsen KM, Hviid A, Vestergaard M, Schendel D,<br />

Wohlfahrt J, Thorsen P, et al. A population-based study of<br />

measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. N<br />

Engl J Med. 2002;347(19):1477-82.<br />

10. Abbott T, Morrison S. No jab – no play and no pay<br />

for child care [Internet]. Canberra ACT: Parliament of<br />

Australia; 2015. 2 p. Available from: http://parlinfo.aph.<br />

gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.<br />

7

Climate Change and <strong>Vector</strong>-Borne<br />

Disease in Kiribati<br />

[Commentary]<br />

Erica Longhurst<br />

Erica Longhurst is a third year medical student at the University of New South Wales, passionate<br />

about environmental health, and who is a big fan of the great outdoors! Her loves are travelling<br />

and learning about people. She is studying in Griffith NSW this year, on clinical placement with my<br />

uni. She’s also super passionate about everything that’s in this edition of <strong>Vector</strong>!<br />

In February 2016, I went on a New Colombo<br />

Plan-sponsored climate change research trip<br />

to Kiribati, a nation of low-lying atolls in the<br />

Pacific Ocean. The islands of Kiribati are on<br />

the equator halfway between Australia and<br />

Hawaii. One of the most important things<br />

that I learnt was how being sustainable is<br />

not that difficult at all, and that the people of<br />

Kiribati are absolute professionals at living in<br />

harmony with their environment. We travelled<br />

to Kiribati to research the social, economic<br />

and environmental effects of climate change.<br />

However, this trip also taught us much about<br />

ourselves and the society that we live in,<br />

Australia. It was an opportunity to see how<br />

those who contribute nothing to global pollution<br />

are suffering from the effects of climate<br />

change.<br />

There is a large focus in the international<br />

community on the environmental implications of<br />

climate change. Whilst this is highly significant,<br />

the impact of climate change on the health of<br />

local communities also needs to be brought to<br />

attention. When I think of this impact on local<br />

people, Kiribati is the first place that comes<br />

to mind. Climate change is responsible for<br />

an array of health issues, primarily the rise<br />

in communicable diseases as a result of the<br />

climate change-induced El Nino Southern<br />

Oscillation (ENSO) effect.[1] <strong>Vector</strong>-borne<br />

diseases such as malaria and dengue fever<br />

are particularly relevant. Increase in average<br />

global temperatures due to raised levels of<br />

greenhouse gases essentially accommodate<br />

these epidemics.[2] Without firstly responding<br />

to the health issues that these populations<br />

face as a result of climate change, many of the<br />

other issues cannot be addressed. In Kiribati,<br />

it is crucial to take measures to avoid future<br />

health consequences such as communicable<br />

diseases, as these people are so susceptible<br />

to the effects of climate change.<br />

8

The people of Kiribati are said to be the<br />

most vulnerable to the implications of climate<br />

change because of the close proximity of<br />

the inhabitants to the coastal regions of their<br />

islands. The ENSO effect is characterised by<br />

irregular warming of the eastern equatorial<br />

Pacific Ocean, and is responsible for raising<br />

average temperatures and inducing higher<br />

rainfall in the Asia Pacific region. Kiribati itself<br />

is only two metres above sea level, and so<br />

faces challenges in this domain. This is a very<br />

significant issue for cooler regions where there<br />

is limited experience or resistance to vectorborne<br />

infectious diseases.[3]<br />

<strong>Vector</strong>-borne diseases have many factors at<br />

play, such as host resistance, the environment,<br />

urbanisation and the pathogens themselves.<br />

The severity and prevalence of vector-borne<br />

diseases depends heavily on the climate, and<br />

thus directly correlates with the ENSO climate<br />

cycles. Temperature, rainfall and humidity<br />

are especially important concerns for vectorborne<br />

diseases.[4] According to the ‘The Sting<br />

of Climate Change’ report, ‘warmer conditions<br />

allow the mosquitoes and the malaria parasite<br />

itself to develop and grow more quickly, while<br />

wetter conditions let mosquitoes live longer and<br />

breed more prolifically’.[5] There is an overall<br />

increase in the potential for disease transmission<br />

due to the change in the ecology of vectors. This<br />

is characterised by quicker mosquito breeding<br />

cycle (thus, higher concentrations), increased<br />

biting rates, and shortened pathogen incubation<br />

periods.[6] If rainfall is excessive, pooled water<br />

can form, which creates breeding sites for<br />

mosquito larvae. There are many factors that<br />

operate in these scenarios, and so there is no<br />

one direct link between climate and mosquito<br />

populations.<br />

For both dengue and malaria, some of the<br />

most effective control measures to reduce<br />

the burden are long-lasting insecticidal bednets,<br />

indoor residual spraying with insecticides,<br />

seasonal malaria chemo-prevention,<br />

intermittent preventive treatment for infants and<br />

during pregnancy, prompt diagnostic testing,<br />

and treatment of confirmed cases with effective<br />

anti-malarial medicines.[7] These measures<br />

have dramatically lowered malaria disease<br />

burden in many Pacific Islander settings over<br />

the years. Thus, prevention is limited to vectorcontrol<br />

measures, which are very difficult to<br />

monitor.<br />

Visiting Kiribati gave me insight into the reality<br />

of climate change and its current impacts<br />

on health. It is clear that there is a distinct<br />

connection between climate change and<br />

vector-borne diseases. This poses particular<br />

challenges for developing nations where<br />

consequences of climate change are most<br />

pronounced. My experiences in Kiribati showed<br />

us raw, personal stories, and we strongly believe<br />

it is imperative to take action immediately.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

None<br />

Conflict of Interest<br />

None declared<br />

Correspondence<br />

e.longhurst1012@gmail.com<br />

References<br />

1. Reiter P. Climate change and mosquito-borne<br />

disease. Environmental health perspectives; 20<strong>11</strong>. 141 p.<br />

121<br />

2. Ebi KL, Lewis ND, Corvalan C. Climate variability<br />

and change and their potential health effects in small<br />

island states: information for adaptation planning in the<br />

health sector. Environmental Health Perspectives; 2006,<br />

1957-1963 p.<br />

3. Haines A, McMichael AJ, Epstein PR. Environment<br />

and health: 2. Global climate change and health.<br />

Canadian Medical Association Journal; 2006, 729-734 p.<br />

4. Woodruff R, Whetton P, Hennessy K, Nicholls N,<br />

Hales S, Woodward A, Kjellstrom, T, Human health and<br />

climate change in Oceania: a risk assessment. Canberra:<br />

Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing; 2003.<br />

5. Perry M. Malaria and dengue the sting in<br />

climate change. Reuters; 2008. Available from:<br />

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-diseaseidUSTRE4AJ2RQ2008<strong>11</strong>20<br />

6. Bezirtzoglou C, Dekas K, Charvalos E. Climate<br />

changes, environment and infection: Facts, scenarios<br />

and growing awareness from the public health community<br />

within Europe. Anaerobe; 20<strong>11</strong>, 2 p.<br />

7. Githeko AK, Lindsay SW, Confalonieri UE, Patz JA.<br />

Climate change and vector-borne diseases: a regional<br />

analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization; 2000.<br />

<strong>11</strong>36-<strong>11</strong>47 p.<br />

9

REFUGEE AND ASYLUM SEEKER UPDATE<br />

MARCH <strong>2017</strong><br />

I MPORTANT UPDATE<br />

• The Immigration Department reduced the deadline asylum seekers must apply for protection visas from 1 year to<br />

60 days. 1<br />

• Affects thousands of asylum seekers. 1<br />

• Those who don’t make the deadline may have their claim overturned giving them no right to work or medicare 1<br />

• These applications are up to 60 pages long with complex medical terms in English, requiring legal advice for<br />

completion, overloading already saturated legal services 1<br />

• IHMS, contracted to provide primary health care +<br />

mental health services on Manus Island and Nauru has<br />

been found to be not registered by the PNG<br />

medical board. 2<br />

- Therefore, 103 staff working at the centre<br />

have been employed illegally. 2<br />

• Recent Dengue outbreak on Nauru (late Feb). 3<br />

Infecting 70 people on Nauru including 10 refugee and<br />

asylum seekers.<br />

- Unconfirmed reports up to 8 asylum seeker<br />

medevaced to Australia mainland for<br />

treatment. 3<br />

• Young male asylum seeker on Manus Island flown to<br />

Australia for treatment 9th Feb following long<br />

standing series of doctors referring the man to get a<br />

pacemaker since August 2016. 4<br />

- The man collapsed Feb 1 and was finally<br />

transferred. This is another example, just like<br />

that of Faysal Ahmed, of complaints being<br />

ignored for a long time 4<br />

• Amnesty International released a<br />

report labelling Australia’s offshore detention<br />

policy as inhuman and abusive 5<br />

o<br />

o<br />

Highlights governments refusal to<br />

honour offer from NZ to resettle 150<br />

refugees and asylum seekers 5<br />

Treatment of these people involves<br />

systematic neglect and cruelty<br />

designed to inflict suffering 5<br />

1<br />

Hart, C. (<strong>2017</strong>, February 26). Asylum seekers’ applications doomed to fail after visa deadline changes, says refugee support service. ABC news. Retrieved from<br />

www.abc.net.au/news/<strong>2017</strong>-02-26/asylum-seekers-issued-with-new-deadline-for-visa-applications/8304766<br />

2<br />

Armstrong, K. (<strong>2017</strong>, March 3). Manus Island health provider ‘operating illegally for three years’: report. SBS news. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/<strong>2017</strong>/03/02/manus-island-health-provider-operating-illegally-three-years-report<br />

3<br />

Riman, I. (<strong>2017</strong>, February 28). A physical attack and a Dengue-fever outbreak cause fear among Nauru detainees. SBS news. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.sbs.com.au/yourlanguage/arabic/en/article/<strong>2017</strong>/02/28/physical-attack-and-dengue-fever-outbreak-cause-fear-among-nauru-detainees<br />

4<br />

Booth, A. (<strong>2017</strong>, February 12). Manus Island asylum seeker with cardiac condition flown to Australia. SBS news. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/<strong>2017</strong>/02/17/manus-island-asylum-seeker-cardiac-condition-flown-australia<br />

5<br />

Jama, H. (<strong>2017</strong>, February 23). Amnesty critical of Australia’s asylum seeker policy. SBS news. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.sbs.com.au/yourlanguage/somali/en/content/amnesty-critical-australias-asylum-seeker-policy<br />

6<br />

Feng, L. (<strong>2017</strong>, March 8). Hungary toughens laws on asylum seekers again. SBS news. Retrieved from:<br />

http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/<strong>2017</strong>/03/08/hungary-toughens-laws-asylum-seekers-again<br />

7<br />

Picture: Deacon, L. (<strong>2017</strong>, February 10). Migrants entering Hungary to be detained in shipping containers on border. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.breitbart.com/london/<strong>2017</strong>/02/10/migrants-entering-hungary-detained-shipping-containers-border/<br />

10

Humanity Lost?<br />

[Feature article]<br />

This article was originally published in the Doctus Project (February <strong>2017</strong>)<br />

Patrick Walker<br />

Patrick is a medical student at Monash University, and the Editor in Chief of non-profit health<br />

journalism organisation the Doctus Project. He is also the Global Health Policy Officer for the<br />

Australian Medical Students’ Association, attended the World Health Assembly recently in<br />

Geneva, and late last year completed a policy internship at the Grattan Institute. Health-wise, his<br />

interests lie mainly in global health and health policy, and outside of the classroom (or hospital)<br />

he’s either reading a novel, writing about something new, or sitting at the piano crunching out a<br />

tune or two. This year he is completing a Bachelor of Medical Science (Hons) with the Centre<br />

for International Child Health and the Royal Children’s Hospital, looking at oxygen systems and<br />

provision of care in low-resource settings. Looking forward, perhaps this line of work might form the<br />

basis of a career, though there’s plenty of time for that to change.<br />

‘We started the revolution holding roses.<br />

Hoping for support from the international<br />

community. Years passed. The roses turned<br />

into guns. But the hope for support continues.<br />

Still, neither roses nor hope helped.’<br />

- Abdulazez Dukhan, Syrian refugee<br />

Trump, with a simple and powerful message:<br />

he wanted to be heard. He wasn’t asking for an<br />

end to the conflict in his ‘beloved Syria’. He was<br />

simply asking for the West – and its perceived<br />

leader, Trump – to acknowledge the human<br />

side of the war. He was asking for humanity in<br />

the West’s response to his story.<br />

Abdulazez Dukhan is one of 4.5 million<br />

people who have fled Syria since the current<br />

conflict began in 20<strong>11</strong>. He is one of the<br />

countless people whose lives have been<br />

destroyed beyond recognition; one of the<br />

countless people forced to leave everything<br />

behind, in search of a safe place to live.<br />

In January, Abdulazez penned a moving<br />

letter to the new American president, Donald<br />

‘Your words matter for us,’ he writes. ‘You<br />

might be able to change our future ‘Dear future<br />

president, we hope that someone can hear our<br />

words. We hope that you do.’<br />

Sadly, his plea has largely fallen on deaf<br />

ears.<br />

<strong>11</strong>

Just two weeks after Dukhan’s letter was<br />

published by Al Jazeera, Trump signed an<br />

executive order banning people from seven<br />

predominantly Muslim countries, including Syria,<br />

from entering the United States (US) for 90<br />

days. The order also placed a blanket ban on<br />

all refugees for 120 days, and Syrian refugees<br />

indefinitely.<br />

of the highest number of forcibly displaced<br />

persons since World War II and unfathomable<br />

atrocities occurring throughout the Middle<br />

East, northern Africa and many other parts of<br />

the world. For many people – most notably the<br />

young and highly educated – these events were<br />

taken to be a clear marker of racism and an<br />

unwillingness to accept difference.<br />

But they were also each the result of a free,<br />

democratic vote. They reflected the view of the<br />

majority. Further, to pass them off as simply<br />

racist, or a blip in the global political agenda,<br />

would be naive and counter-productive.<br />

The ban is currently suspended thanks to a<br />

federal judge temporarily blocking the executive<br />

order, but Trump’s message can be heard loud<br />

and clear. His response to the Syrian War and<br />

the current refugee crisis is to look the other<br />

way; to close the doors to those most in need<br />

of help.<br />

When I first watched the video of Abdulazez<br />

Dukhan’s letter to Trump, I was brought to tears.<br />

Dukhan’s poignant words brought the horrors he<br />

had endured suddenly to life. For a moment, I felt<br />

I was able to gain a tiny glimpse into the harsh<br />

reality of life for the millions of Syrians living in<br />

a conflict zone.<br />

Perhaps this should not come as too much of<br />

a surprise. Trump’s protectionism and stance on<br />

immigration are neither novel nor unexpected.<br />

Rather, they can be viewed as a symptom of<br />

a broader rise in nationalism, in response to a<br />

global refugee crisis that continues to worsen.<br />

2016 was a year of many things, but<br />

prominent among them were nationalism,<br />

division, and an increasingly powerful global<br />

Right. Brexit and the rise of an assortment of<br />

right-wing parties defined politics in Europe.<br />

Across the Atlantic, Trump was elected to the<br />

Oval Office on a fervent anti-establishment and<br />

pro-US, protectionist agenda. Back home in<br />

Australia, we saw the re-emergence of Pauline<br />

Hanson and her far-right, anti-immigration One<br />

Nation party.<br />

All these events occurred in the context<br />

This visceral response is by no means<br />

unusual or unexpected. It is the same as the<br />

West’s response to the ‘boy in the ambulance’<br />

12

(five year-old Omran Daqneesh, injured by a<br />

blast in Aleppo in August last year) or to horrific<br />

images of the dead body of three year-old Aylan<br />

Kurdi washed up on a Turkish shore.<br />

It is human nature to feel outrage at injustice<br />

when it is put in front of us. It is not, however,<br />

human nature to react the same way to atrocities<br />

removed from one’s own existence and social<br />

or political sphere. Without these images and<br />

videos that become – for better or for worse –<br />

perverse icons of death and destruction, it is all<br />

too easy for us to simply turn away.<br />

This tendency means we often lose sight of<br />

the human side of tragic events to which we find<br />

ourselves unable to relate. This is exactly what<br />

we have seen in our politicians and our leaders.<br />

And it is in many cases exactly what we have<br />

seen in ourselves. Instead of compassion and<br />

unity, we have responded to horrors such as<br />

those going on in Syria with disaffection and, at<br />

times, apathy. Instead of reaching out to those in<br />

need, we have instead turned inwards, creating<br />

division and, on the other end, despair.<br />

The unprecedented political phenomenon of<br />

2016 is perhaps best encapsulated by social<br />

psychologist Jonathan Haidt. In a remarkably<br />

insightful and prescient essay entitled ‘When<br />

and why nationalism beats globalism’, Haidt<br />

unpacks the rise in nationalism we have seen<br />

in the past year, and tries to answer the simple<br />

question: ‘What on earth is going on in the<br />

Western democracies?’<br />

By resisting change and immigration, Haidt<br />

argues that nationalists are not, as many<br />

believe, being selfish or somehow morally<br />

inferior to those embracing change. Far from<br />

it. Rather than inciting discrimination, he writes,<br />

they are working to preserve their nation and<br />

culture. The division between nations that can<br />

arise from this attitude is a by-product, rather<br />

than an intended consequence.<br />

The way to tackle this, then, is not to label<br />

nationalist or anti-immigration sentiment as<br />

‘racism pure and simple’. As Haidt notes, ‘If we<br />

want to understand the recent rise of right-wing<br />

populist movements, then ‘racism’ can’t be the<br />

stopping point; it must be the beginning of the<br />

inquiry.’<br />

Rather than labelling the majorities who<br />

voted for Brexit, Trump or Hanson as racist or<br />

ignorant, we as a society need to understand<br />

their motives, and why they have turned to the<br />

Right for answers. We need to understand why<br />

so many of us are seemingly willing to turn a<br />

blind eye to horrors occurring outside of our<br />

immediate vicinity. We need to understand why<br />

we have lost compassion in our response to the<br />

plight of Syria.<br />

<strong>2017</strong> can be different from the division we<br />

saw in 2016, but only if we resist the urge to vilify<br />

the ‘Other’, regardless of who that ‘Other’ is – a<br />

Muslim refugee, a status quo conservative, a<br />

member of the educated elite, or a right-wing<br />

authoritarian.<br />

Instead, creating a space of mutual<br />

understanding between people of differing<br />

opinions may help bridge the gap that has<br />

formed between the Right and the Left; the<br />

Nationalists and the Globalists; the Educated<br />

and the Uneducated; the East and the West.<br />

By doing this, we will start on the path towards<br />

finding an adequate response to Dukhan’s<br />

plea to Trump. And, somewhere along the way,<br />

maybe we will find that humanity that seems to<br />

have gone missing.<br />

Photo credit<br />

Abdulazez Dukhan<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Doctus Project<br />

Conflict of Interest<br />

None declared<br />

Correspondence<br />

patrick.walker@amsa.org.au<br />

13

Redefining Women’s Health:<br />

A Noncommunicable Diseases Perspective<br />

[Feature Article]<br />

Charlotte O’Leary<br />

Charlotte has completed 4 years of medical school at Monash University. She is currently undertaking<br />

a Bachelor of Medical Science (Honours) at the Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of<br />

Oxford. Charlotte undertook a 3-month internship at the World Health Organization in early <strong>2017</strong> in the<br />

Global Coordination Mechanism for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).<br />

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) –<br />

mainly cardiovascular diseases, cancers,<br />

chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes –<br />

represent a major challenge for sustainable<br />

development in the twenty-first century. In 2015,<br />

NCDs were responsible for 39.5 million (70%)<br />

of the world’s deaths, with more than 40% (16<br />

million) dying prematurely, or before the age of<br />

70.[1] NCDs affect people of all ages in high,<br />

middle and low-income countries. In particular,<br />

women and girls face unique challenges in<br />

the growing NCD epidemic<br />

due to pervasive gender<br />

inequality, disempowerment and<br />

discrimination. Without specific<br />

attention to the needs of women<br />

and adolescent girls, the impact<br />

of NCDs threatens to unravel the<br />

fragile health gains made over<br />

the past decades and undermine future efforts<br />

to ensure gender equity and healthy lives for all.<br />

The problem<br />

Gender inequality and NCDs<br />

NCDs have been the<br />

leading causes of death<br />

among women globally for the<br />

past three decades, and now,<br />

NCDs account for nearly 65%<br />

of female deaths worldwide.<br />

Nearly two thirds of illiterate people in the<br />

world are women, and this ratio has remained<br />

unchanged for two decades.[2] Consequently,<br />

women have had fewer opportunities to improve<br />

their health literacy and equip themselves with<br />

transferable skills that will enable them to be<br />

advocates for their own health.<br />

Women face unique challenges accessing<br />

healthcare due to their lower socioeconomic,<br />

political and legal status compared<br />

to men. The critical importance of<br />

prevention and early diagnosis of<br />

NCDs requires regular contact with<br />

the healthcare system. In some<br />

cultures, the health of a woman<br />

is often seen as secondary to the<br />

health of a man, and she may be<br />

denied access to healthcare when resources<br />

are limited. Even when given the choice,<br />

women are more likely than men to invest their<br />

money in the health of their children and other<br />

family members, rather than prioritising their<br />

own health.<br />

NCDs have been the leading causes of<br />

death among women globally for the past three<br />

decades, and now, NCDs account for nearly<br />

65% of female deaths worldwide. Pervasive<br />

gender inequality particularly affects the health<br />

of women and girls, influencing their ability to<br />

improve their health literacy, access healthcare<br />

services, achieve economic empowerment<br />

and financial security and live with NCDs free<br />

from stigma and discrimination.<br />

Many women may experience financial<br />

vulnerability due to high out-of-pocket<br />

healthcare costs. Lower access to formal paid<br />

employment may deny women the social and<br />

financial securities required to insure them<br />

against poor health.<br />

Additionally, women are too frequently<br />

viewed as commodities, and women living<br />

with a chronic disease may face alienation<br />

14

and discrimination. This is often due to the<br />

emphasis in certain social or cultural settings<br />

on a woman’s suitability for marriage and<br />

childbearing, which may be affected by chronic<br />

diseases.<br />

The caring burden<br />

Beyond their personal experiences with<br />

NCDs, women are indirectly affected by the<br />

increase in the burden of chronic diseases due<br />

to their traditional role as carers in families and<br />

communities. In a survey of 10,000 women from<br />

around the world, half the women were caring<br />

for a family member with an NCD, with one in five<br />

realising their own economic opportunities were<br />

diminished as a result.[3] Another study from the<br />

United States revealed that women make 80%<br />

of the health care decisions for their families,<br />

yet often go without health care coverage<br />

themselves.[4] Caregiving responsibilities can<br />

threaten or disrupt the education of adolescent<br />

girls, and often impacts women in their most<br />

productive years. Paid work decreases<br />

because of the burden of caring for people<br />

living with NCDs and reduces the economic<br />

contribution of women. This loss of productivity<br />

is felt by the whole society. The large amount of<br />

unpaid work undertaken by women in the family<br />

and community at all levels of society is highly<br />

under-appreciated.<br />

Vulnerability to NCD risk factors<br />

Women are uniquely vulnerable to the four<br />

major risk factors for NCDs, namely physical<br />

inactivity, poor nutrition, tobacco use and<br />

excessive alcohol intake. Improved social<br />

status and economic empowerment has<br />

contributed to an alarming increase in cigarette<br />

smoking amongst women and girls. The World<br />

Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the<br />

proportion of female smokers will rise from 12%<br />

in 2010 to 20% in 2025. Deaths attributable<br />

to tobacco use amongst women are also<br />

projected to increase from 1.5 to 2.5 million from<br />

2004 to 2030.[5] Women’s increasing social and<br />

economic status, especially in low and middleincome<br />

countries, has made them a prime target<br />

for the tobacco industry. This is especially true<br />

in Asia where regulation of tobacco advertising<br />

is lacking. Aside from the immoral promotion of<br />

health-harming products, the objectification of<br />

women is entrenched in tobacco advertising.<br />

Women’s bodies are exploited for the sale of<br />

cigarettes to men, whilst simultaneously and<br />

paradoxically, a message of health and beauty<br />

through tobacco consumption is conveyed to<br />

women and girls.[5]<br />

A similar trend is seen in alcohol consumption,<br />

with female alcohol consumption now rivalling<br />

male consumption, closing a historic divide.<br />

[6] Women and girls around the world are less<br />

likely to be physically active than boys and men<br />

due to sociocultural, economic and physical<br />

limitations imposed on them. In many cultures,<br />

women are largely responsible for food<br />

preparation. As a consequence, women often<br />

eat least and last in the family, compromising<br />

their nutrition. Additionally, inhalation of indoor<br />

cooking fuels is a well-known risk factor for<br />

chronic respiratory disorders, and this risk is<br />

borne disproportionately by women.[7] The list<br />

goes on.<br />

The way forward<br />

So how might we move forward at this<br />

critical time to ensure that we are effectively<br />

addressing the unique needs of women in<br />

the NCD epidemic? This problem is evidently<br />

complex and multifaceted. Presented here are<br />

some possible approaches, to firstly broaden<br />

our understanding of women’s health to include<br />

NCDs, and secondly to ensure that women are<br />

empowered and engaged in their own health.<br />

Defining women’s health<br />

One important step forward is to adopt a<br />

broader and more holistic definition of women’s<br />

health. Historically, the field of women’s<br />

health has focused on reproductive health,<br />

and consequently, considerable gains have<br />

been made in reducing maternal and newborn<br />

mortality and morbidity. While these gains are<br />

positive and important, it is equally important<br />

that the definition of women’s health not be<br />

confined to reproductive health. As Norton et al.<br />

15

posit in Women’s Health: A New Global Agenda,<br />

the currently narrow approach to women’s<br />

health firstly limits opportunities to effectively<br />

improve the health of the maximum number of<br />

women, and secondly, discriminates against<br />

women who do not have children.[8]<br />

In recent years, many international advocacy<br />

efforts have thus been made to expand this<br />

definition, and encompass a more holistic view<br />

of the health challenges faced by women. Such<br />

focus areas include, but are not limited to: the<br />

burden of NCDs in women, including mental<br />

health; the caring roles of women; and sexual<br />

and interpersonal violence. Additionally, the<br />

health of women must be considered across<br />

the whole life course. A reproductive focus<br />

risks excluding pre-adolescent girls<br />

and older women, all of whom face<br />

unique challenges in navigating<br />

their health in a climate of gender<br />

inequity. Indeed, women who have<br />

been through menopause have<br />

substantially increased risk of<br />

NCDs. Thus a focus on older women<br />

should be an integral of a life course<br />

approach to women’s health.<br />

Integrating NCDs into other health programs<br />

There are great opportunities to capitalise on<br />

existing healthcare services to better address<br />

the needs of women in the NCD epidemic. There<br />

is enormous opportunity to expand existing<br />

reproductive, communicable disease (such<br />

as HIV and tuberculosis) and sexual health<br />

services to incorporate NCDs. In particular,<br />

maternal and reproductive healthcare services<br />

are targeted at women, allowing healthcare<br />

to be delivered in an environment that is<br />

acceptable to, and accessible by, women and<br />

adolescent girls. Given the unique challenges<br />

faced by women in the NCD epidemic, these<br />

existing services can be broadened to include<br />

health promotion activities around NCD risk<br />

factors, early diagnosis and screening services<br />

(including breast and cervical cancer screening)<br />

and referral and treatment services. This will<br />

ensure that women are empowered to improve<br />

the health of themselves, their families and<br />

The impact of educating<br />

women has multigenerational<br />

effects due to their central<br />

position in the community, so<br />

improving women’s engagement<br />

with health promotion is a high<br />

yield intervention.<br />

communities. One such approach might be<br />

to follow up women with gestational diabetes<br />

after birth and to provide screening checks and<br />

education around good nutrition for mothers<br />

and children in order to prevent the development<br />

of diabetes. There is growing evidence for the<br />

feasibility and effectiveness of health system<br />

integration to prevent and control NCDs. [9,10]<br />

Women in medical research<br />

There is scope for the broader scientific and<br />

research community to ensure that women are<br />

equally represented in medical research. It is<br />

increasingly apparent that NCDs do not affect<br />

men and women equally. Women who smoke<br />

have a 25% greater relative risk of ischaemic<br />

heart disease than men who<br />

smoke.[<strong>11</strong>] Women suffer<br />

worse cardiovascular disease<br />

as a consequence of type 2<br />

diabetes than men,[12] and<br />

women with type 1 diabetes<br />

have a roughly 40% greater risk<br />

of all-cause mortality than men.<br />

[13] However, taking a focused<br />

biomedical approach is not<br />

sufficient to address the burden of NCDs in<br />

women. Medical research must also consider<br />

the social and cultural effects of gender<br />

inequity in order to fully appreciate the health<br />

outcomes of women with NCDs. Increasing<br />

attention to gender-disaggregated of research<br />

data has been recognised in the Sustainable<br />

Development Goals as an important tool for<br />

discovering these important gender disparities<br />

in illness.[14]<br />

Engaging women at every level<br />

Lastly, increasing female participation in<br />

decision-making will ensure the challenges<br />

faced by women are reflected in policies<br />

for health and sustainable development.<br />

Participation happens at every level. In local<br />

communities, women are attuned to the needs of<br />

other people, and as evident above, make many<br />

of the health related decisions in the community.<br />

There is a huge opportunity to harness their<br />

strength and knowledge to be a driving force<br />

16

for the prevention of NCDs. The impact of<br />

educating women has multigenerational effects<br />

due to their central position in the community,<br />

so improving women’s engagement with health<br />

promotion is a high yield intervention. There must<br />

be a concerted global effort to remove barriers<br />

to female participation in politics and high-level<br />

decision-making. Until this is achieved, it will<br />

be challenging to ensure that the multifaceted<br />

effects of gender inequity are accounted for in<br />

national and international policy.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Noncommunicable diseases are one of the<br />

biggest threats to health in an increasingly<br />

globalised world. Addressing gender inequity<br />

will be a necessary component of the solution.<br />

The health of women concerns everyone, and is<br />

far more than an economic, political or cultural<br />

issue. Ultimately, ensuring every woman and<br />

girl has the right to access the utmost level of<br />

health and wellbeing is an issue of human rights<br />

and justice.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

None<br />

Conflict of Interest<br />

None declared<br />

Correspondence<br />

charlotte.a.oleary@gmail.com<br />

2014;25(4):1507-13.<br />

5. World Health Organization. Gender, women, and<br />

the tobacco epidemic. World Health Organization; 2010.<br />

6. Slade T, Chapman C, Swift W, et al Birth cohort<br />

trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and<br />

alcohol-related harms in men and women: systematic<br />

review and metaregression BMJ Open 2016;6:e0<strong>11</strong>827.<br />

doi: 10.<strong>11</strong>36/bmjopen-2016-0<strong>11</strong>827<br />

7. World Health Organization. Household air pollution<br />

and health [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization.<br />

<strong>2017</strong> [cited 27 May <strong>2017</strong>]. Available from: http://www.who.<br />

int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs292/en/<br />

8. Peters SA, Woodward M, Jha V, Kennedy S, Norton<br />

R. Women’s health: a new global agenda. BMJ Global<br />

Health. 2016 Nov 1;1(3):e000080.<br />

9. Chamie G, Kwarisiima D, Clark TD, Kabami J, Jain<br />

V, Geng E, Petersen ML, Thirumurthy H, Kamya MR, Havlir<br />

DV, Charlebois ED. Leveraging rapid community-based<br />

HIV testing campaigns for non-communicable diseases<br />

in rural Uganda. PloS one. 2012 Aug 20;7(8):e43400.<br />

10. Janssens B, Van Damme W, Raleigh B, Gupta J,<br />

Khem S, Soy Ty K, Vun MC, Ford N, Zachariah R. Offering<br />

integrated care for HIV/AIDS, diabetes and hypertension<br />

within chronic disease clinics in Cambodia. Bulletin of the<br />

World Health Organization. 2007 Nov;85(<strong>11</strong>):880-5.<br />

<strong>11</strong>. Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a<br />

risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared<br />

with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of<br />

prospective cohort studies<br />

12. Woodward M, Peters SA, Huxley RR . Diabetes and<br />

the female disadvantage. Women’s Health (Lond Engl).<br />

2015; <strong>11</strong>: 833-839.<br />

13. Huxley RR, Peters SA, Mishra GD, Woodward M.<br />

Risk of all-cause mortality and vascular events in women<br />

versus men with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and<br />

meta-analysis. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.<br />

2015 Mar 31;3(3):198-206.<br />

14. United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030<br />

Agenda for Sustainable Development. Geneva: United<br />

Nations. 25 Sept 2015.<br />

References<br />

1. World Health Organization. NCD mortality and<br />

morbidity [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization.<br />

<strong>2017</strong> [cited 27 May <strong>2017</strong>]. Available from: http://www.who.<br />

int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/<br />

2. The World’s Women 2015. 2015. United Nations<br />

Statistics Division [Internet]. Accessed from: https://<br />

unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/chapter3/chapter3.html<br />

3. Insights from 10,000 women on the impact of<br />

NCDs [Internet]. Arogya World. 2014. Accessed from:<br />

http://arogyaworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/<br />

Arogya-Full-Report-For-Web.pdf<br />

4. Matoff-Stepp S, Applebaum B, Pooler J, Kavanagh<br />

E. Women as health care decision-makers: Implications<br />

for health care coverage in the United States.<br />

Journal of health care for the poor and underserved.<br />

17

Healthcare in Conflict Zones<br />

[Feature Article]<br />

Michael Wu<br />

Michael Wu graduated with a B.Pharm from the University of Sydney in 2012 with a major<br />

from the Clinical Excellence Commission focusing on IV to Oral Switch Therapy. Since then, my<br />

passions have grown from Infectious Diseases to just about everything. It’s a problem. I’d like to<br />

work all over the world at some stage, whether in Trauma or Ophthalmology.<br />

Introduction<br />

Medical neutrality in war-ravaged areas<br />

is the cornerstone of healthcare provision in<br />

conflict zones. However, weaponisation of<br />

healthcare – the deliberate destruction or<br />

removal of access to healthcare as a means<br />

of hamstringing opponents – has emerged as<br />

a concerning and common practice in modern<br />

military engagements. Medical neutrality was<br />

formalised in 1864 with the inception of the First<br />

Geneva Convention, which sought to establish<br />

a permanent ‘neutral’ agency that would deliver<br />

medical aid and services to sick and wounded<br />

combatants.[1] There was consensus amongst<br />

governments that armed conflict, no matter<br />

how violent, must maintain some semblance<br />

of compassion and humanity. This recognition<br />

was at the core of the message the Geneva<br />

Convention sent; that a line must be drawn<br />

in war and conflict. Recent years have seen<br />

military forces and governments ignore this<br />

sentiment, with clear violations of the Geneva<br />

Convention, from deliberate bombings and<br />

executions of doctors, nurses, pharmacists,<br />

medical students, and pharmacy students<br />

in Syria and Somalia, for example. Indeed, it<br />

would appear that many countries are either<br />

implicated in, or turn a blind eye to, atrocities<br />

resulting from violations of the Geneva<br />

Convention.<br />

Dr Kathleen Thomas has experienced<br />

this degeneration in the standard of warfare<br />

first-hand. Her story has become a landmark<br />

in this field. As an Australian doctor, she was<br />

responsible for an Intensive Care Unit at a<br />

Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) hospital in<br />

Kunduz, Afghanistan, when it was bombed by<br />

an American AC130 gunship in October, 2015.<br />

MSF had released the GPS coordinates of their<br />

hospital to American forces in the region days<br />

prior; their location was known. Repeated air<br />

strikes resulted in 42 fatalities, including 12<br />

staff, 24 patients and 4 caretakers, with dozens<br />

more wounded. MSF maintains that the attack<br />

was deliberate and has called for independent<br />

investigations by multiple bodies.[2] One must<br />

question why American forces, or indeed<br />

any government, would condone the attack<br />

of healthcare facilities. Similarly, however,<br />

it is important to realise that from a military<br />

perspective, this weaponisation of healthcare<br />

makes sense: it removes a valuable resource<br />

to guerrilla forces, that of neutral healthcare.<br />

Healthcare and conflict in Syria<br />

Syria is now the most dangerous nation in<br />

the world according to the Global Peace Index.<br />

[3] The Syrian civil war has left much of the<br />

country’s population displaced since beginning<br />

in 20<strong>11</strong>. As early as March that year, the country<br />

saw its first documented execution of a doctor.<br />

Subsequently, the attrition of healthcare in<br />

Syria has been the result of direct and violent<br />

attacks on health workers, as well as a mass<br />

exodus of health workers fleeing persecution.<br />

These direct attacks are mostly carried out by<br />

pro-government forces, and have manifested<br />

as “attacks on health facilities, executions,<br />

imprisonment or threat of imprisonment,<br />

unlawful disappearance (i.e. kidnapping),<br />

abduction, and torture sometimes leading to<br />

18

death” [4]. According to data from Physicians<br />

for Human Rights, 796 health workers were<br />

killed between March 20<strong>11</strong> and December<br />

2016. Of these deaths, shelling and bombing<br />

accounted for just over<br />

half (55%), followed by<br />

shooting (23%), torture<br />

(13%), and execution<br />

(8%).[5] In addition to<br />

health worker fatalities,<br />

military forces have also<br />

targeted health facilities.<br />

This escalated in late September 2015, when<br />