InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 10

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

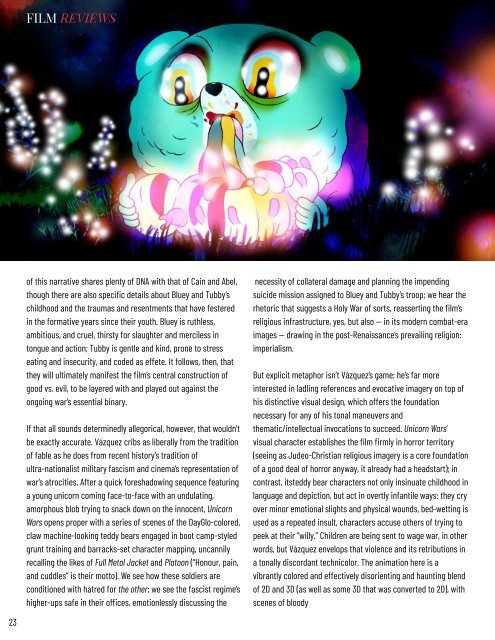

FILM REVIEWS<br />

of this narrative shares plenty of DNA with that of Cain and Abel,<br />

though there are also specific details about Bluey and Tubby’s<br />

childhood and the traumas and resentments that have festered<br />

in the formative years since their youth. Bluey is ruthless,<br />

ambitious, and cruel, thirsty for slaughter and merciless in<br />

tongue and action; Tubby is gentle and kind, prone to stress<br />

eating and insecurity, and coded as effete. It follows, then, that<br />

they will ultimately manifest the film’s central construction of<br />

good vs. evil, to be layered with and played out against the<br />

ongoing war’s essential binary.<br />

If that all sounds determinedly allegorical, however, that wouldn’t<br />

be exactly accurate. Vázquez cribs as liberally from the tradition<br />

of fable as he does from recent history’s tradition of<br />

ultra-nationalist military fascism and cinema’s representation of<br />

war’s atrocities. After a quick foreshadowing sequence featuring<br />

a young unicorn coming face-to-face with an undulating,<br />

amorphous blob trying to snack down on the innocent, Unicorn<br />

Wars opens proper with a series of scenes of the DayGlo-colored,<br />

claw machine-looking teddy bears engaged in boot camp-styled<br />

grunt training and barracks-set character mapping, uncannily<br />

recalling the likes of Full Metal Jacket and Platoon (“Honour, pain,<br />

and cuddles” is their motto). We see how these soldiers are<br />

conditioned with hatred for the other; we see the fascist regime’s<br />

higher-ups safe in their offices, emotionlessly discussing the<br />

necessity of collateral damage and planning the impending<br />

suicide mission assigned to Bluey and Tubby’s troop; we hear the<br />

rhetoric that suggests a Holy War of sorts, reasserting the film’s<br />

religious infrastructure, yes, but also <strong>—</strong> in its modern combat-era<br />

images <strong>—</strong> drawing in the post-Renaissance’s prevailing religion:<br />

imperialism.<br />

But explicit metaphor isn’t Vázquez’s game; he’s far more<br />

interested in ladling references and evocative imagery on top of<br />

his distinctive visual design, which offers the foundation<br />

necessary for any of his tonal maneuvers and<br />

thematic/intellectual invocations to succeed. Unicorn Wars’<br />

visual character establishes the film firmly in horror territory<br />

(seeing as Judeo-Christian religious imagery is a core foundation<br />

of a good deal of horror anyway, it already had a headstart); in<br />

contrast, itsteddy bear characters not only insinuate childhood in<br />

language and depiction, but act in overtly infantile ways: they cry<br />

over minor emotional slights and physical wounds, bed-wetting is<br />

used as a repeated insult, characters accuse others of trying to<br />

peek at their “willy.” Children are being sent to wage war, in other<br />

words, but Vázquez envelops that violence and its retributions in<br />

a tonally discordant technicolor. The animation here is a<br />

vibrantly colored and effectively disorienting and haunting blend<br />

of 2D and 3D (as well as some 3D that was converted to 2D), with<br />

scenes of bloody<br />

23