Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

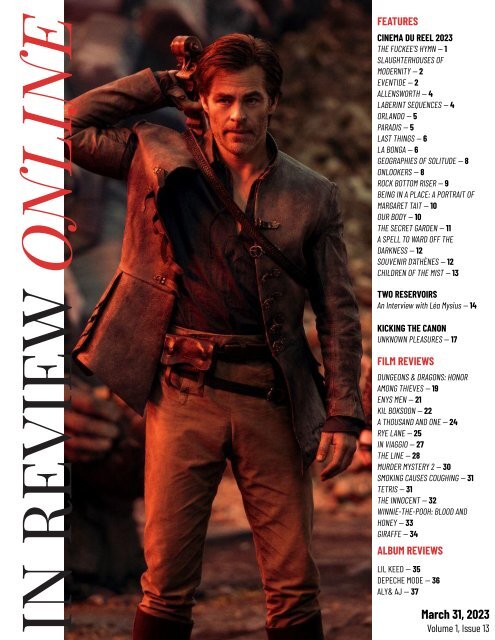

IN REVIEW ONLINE<br />

FEATURES<br />

CINEMA DU REEL 2023<br />

THE FUCKEE’S HYMN — 1<br />

SLAUGHTERHOUSES OF<br />

MODERNITY — 2<br />

EVENTIDE — 2<br />

ALLENSWORTH — 4<br />

LABERINT SEQUENCES — 4<br />

ORLANDO — 5<br />

PARADIS — 5<br />

LAST THINGS — 6<br />

LA BONGA — 6<br />

GEOGRAPHIES OF SOLITUDE — 8<br />

ONLOOKERS — 8<br />

ROCK BOTTOM RISER — 9<br />

BEING IN A PLACE: A PORTRAIT OF<br />

MARGARET TAIT — 10<br />

OUR BODY — 10<br />

THE SECRET GARDEN — 11<br />

A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE<br />

DARKNESS — 12<br />

SOUVENIR D’ATHÈNES — 12<br />

CHILDREN OF THE MIST — <strong>13</strong><br />

TWO RESERVOIRS<br />

An Interview with Léa Mysius — 14<br />

KICKING THE CANON<br />

UNKNOWN PLEASURES — 17<br />

FILM REVIEWS<br />

DUNGEONS & DRAGONS: HONOR<br />

AMONG THIEVES — 19<br />

ENYS MEN — 21<br />

KIL BOKSOON — 22<br />

A THOUSAND AND ONE — 24<br />

RYE LANE — 25<br />

IN VIAGGIO — 27<br />

THE LINE — 28<br />

MURDER MYSTERY 2 — 30<br />

SMOKING CAUSES COUGHING — 31<br />

TETRIS — 31<br />

THE INNOCENT — 32<br />

WINNIE-THE-POOH: BLOOD AND<br />

HONEY — 33<br />

GIRAFFE — 34<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

LIL KEED — 35<br />

DEPECHE MODE — 36<br />

ALY& AJ — 37<br />

March 31, 2023<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1, <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>13</strong>

CINÉMA DU RÉEL 2023<br />

THE FUCKEE’S HYMN<br />

Travis Wilkerson<br />

The ghosts of the Vietnam War now outrank the survivors. After<br />

fifty years, it may as well be ancient history, with Ken Burns’<br />

recent documentary, The Vietnam War, solidifying its place as a<br />

research project not unlike his Civil War. Kissinger’s still around,<br />

of course, and every once in a while, one may spot the golden<br />

“VIETNAM VETERAN” adorning a black hat, but the war’s individual<br />

moments have been long subsumed into a mythic tale about the<br />

limits of American hubris. But, the children of those veterans still<br />

carry the residual traumas of those moments, and in them, the<br />

ghosts find their vessels.<br />

Travis Wilkerson, director of radical political documentaries such<br />

as the magnificent An Injury to One, was one such child. His last<br />

few projects have been increasingly personal, focusing mostly on<br />

the sins and stories of his own family to illustrate larger political<br />

issues. His latest, The Fuckee’s Hymn, continues the pattern by<br />

amending his 2011 Distinguished Flying Cross with more stories<br />

about Wilkerson’s late father and his role in the Vietnam War.<br />

Here, Wilkerson takes a more philosophical approach by<br />

questioning the role of stories in the war, as well as how those<br />

stories directly affected his father. “Can a story kill you?”<br />

Wilkerson teases. You probably know the answer.<br />

Dense forest growth in high contrast black-and-white dominates<br />

the frame for most of The Fuckee’s Hymn’s running time.<br />

Wilkerson’s movies usually play like a visual radio show, so the<br />

slow series of landscape shots merely serve as context for the<br />

wider story. Here, the forest and surrounding flora are eventually<br />

revealed to be the land around his parents’ house, with the house<br />

itself briefly making a cameo (though only its darkest recesses<br />

are shown with a sliver of light to mark a bathroom in a long<br />

hallway). Meanwhile, Wilkerson narrates his story with the<br />

circuitous rhythms of a Faulkner character, often interrupting<br />

himself, starting the story again, or allowing the strength of a<br />

1

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

tangential story take over. With his commentary on the deadly<br />

alchemy of storytelling, the curse of family memory, and the<br />

ghosts that live in the margins of his father’s legacy, Wilkerson<br />

has forged a true Vietnam Gothic.<br />

“Wilkerson [makes] his subject,<br />

as personal a subject as one<br />

can get, the centerpiece of our<br />

collective fears, guilt, and<br />

doubt about the war.<br />

After meditating on the power of stories and myths “that can turn<br />

killers into heroes,” we learn the specifics of the elder<br />

Wilkerson’s Vietnam career. He joins the army as it provides the<br />

only way for a blue-collar kid to learn how to fly, he becomes the<br />

youngest pilot to graduate from his base in Alabama, he’s<br />

awarded one of the most prestigious medals a pilot can achieve,<br />

he’s considered a hero, and he regrets all of it. Travis then<br />

supplies his own memories of his father as he knew him: an<br />

esteemed trauma doctor and professor who saved lives, only to<br />

succumb to a form of cancer that only agent orange can induce.<br />

Even if he tried to live through acts of service to exorcize the<br />

ghosts of Vietnam, the ghosts can still occupy the body.<br />

Wilkerson repeatedly teases a story that simultaneously put his<br />

father in Vietnam, made his father regret Vietnam, and ultimately<br />

killed his father; but a secondary story haunts both Wilkerson<br />

and the film itself. Flashes of red interrupt the serene forest<br />

imagery, a face appears in the shadows. Eventually, Wilkerson<br />

recounts the spiritual horror of watching Hong Sen Nguyen’s The<br />

Abandoned Field, a film that depicts American pilots as<br />

unrelenting monsters to a small Vietnamese village and ends<br />

with both Vietnamese and American boys fatherless. Clips of the<br />

film dissolve into the American woods during the breaks in<br />

Wilkerson’s monologue, providing the only war imagery and the<br />

only faces visible in the film. They, too, haunt.<br />

Films like The Fuckee’s Hymn, such as James N. Kienetz Wilkins’<br />

Indefinite Pitch, remain interesting so long as the radio play<br />

format holds your attention. Thankfully, Wilkerson pauses,<br />

enunciates, grumbles, and teases enough to make his subject, as<br />

personal a subject as one can get, the centerpiece of our<br />

collective fears, guilt, and doubt about the war. Storytelling, that<br />

ancient art, belongs to the characters of the Gothic like the<br />

neighbors of Absalom, Absalom! who corner the novel’s Quentin<br />

and ramble lies about half-forgotten pasts, then begin again as if<br />

telling the story in the right way will hex the ghosts back into<br />

history. Wilkerson’s story is also one of half-remembrances and<br />

stories that earn a warning: “even if they’re not real, they’re true.”<br />

But, he doesn’t tell his story again. Stories can kill you. — ZACH<br />

LEWIS<br />

EVENTIDE<br />

Sharon Lockhart<br />

In her remarkable 2021 book on James Benning’s Ten Skies, critic<br />

and scholar Erika Balsom remarks that the film “at once rewards<br />

a close attention to detail and sanctions wayward drift.” It’s a<br />

lovely turn of phrase, and one quite applicable to Sharon<br />

Lockhart’s new short film Eventide. The two artists — Benning<br />

SLAUGHTERHOUSES OF MODERNITY<br />

Heinz Emigholz<br />

“Never before has Emigholz quite editorialized his architectural tours. Title cards with names of cities and dates of the works<br />

usually give the only context to his series of shots, allowing the viewer to infer any meaning themselves. Perhaps a dilapidated<br />

building in the countryside followed by a pristine building in the city, both made in the same year by the same architect, is a<br />

commentary on how and what the government funds. Perhaps an empty auditorium shows how much community life has<br />

dwindled. Film studies professors typically label this as “structuralist,” and the process can be just as fun as it is quintessentially<br />

snobbish. This is not the case for Slaughterhouses, as Emigholz conducts lectures about the politics and history of each work and<br />

lays out the connections explicitly.” — ZACH LEWIS [Originally published as part of InRO’s NYFF 2022 coverage.]<br />

2

CINÉMA DU RÉEL<br />

and Lockhart — have cited each other’s works as influences in<br />

their own, and even published a book together last year, titled<br />

Over Time. Fittingly, both artists’ works are deceptively simple to<br />

describe, while simultaneously invoking larger formal and<br />

philosophical ideas about duration, stasis, and movement. As<br />

Chus Martinez writes, “her [Lockhart’s] images determine our<br />

understanding of time and action through the grieving<br />

discrepancy between aesthetic expectation and the seeming<br />

unity of time passing… a potentially endless stasis difficult to<br />

recognise or delimit in terms of action or conclusion.”<br />

The simplest thing to do with Lockhart’s films is, of course, to<br />

look at them. Eventide begins with a single, static camera setup.<br />

It does not cut or move for the next 30 minutes. The horizon line<br />

cuts evenly across the frame; a body of water (this writer is not<br />

sure if it is an ocean or a lake) with small, gently lapping waves is<br />

on screen left, while a rocky shoreline and scattered shrubbery<br />

extend across the frame to the right. A particularly large bit of<br />

foliage sits in the middle of the image. It’s dark, although it’s at<br />

first unclear whether it is dawn or dusk. A man enters frame left,<br />

walking across the ground with a flashlight. Eventually, another<br />

body, a woman, emerges from the same direction just as the first<br />

person walks behind some of the shrubs and disappears from<br />

the frame. The second figure is further back in the depth of field,<br />

momentarily alone until the man re-emerges from behind the<br />

shrubs; he's now on the same focal plane as the woman. While<br />

these figures slowly traverse the grounds, their flashlights<br />

pointed down in search of an unknown something or other, the<br />

sky darkens, and stars become more visible.<br />

At around the eight-minute mark, a third figure appears, hitherto<br />

fully hidden by the shrubs and their distance from the camera (a<br />

game of focal lengths). A tiny pinprick of light appears in the<br />

deep background, suggesting now a fourth body. One of the<br />

people moves closer to the water, and the brightness of their<br />

flashlight begins reflecting off of the surface of the water, a<br />

lovely tinkling, shimmering light. Two more figures arrive; it’s<br />

unclear at first if one of them was the light source in the<br />

distance and has simply walked closer to the main point of<br />

action, but eventually that’s revealed, too. Six people are now<br />

wandering the ground, each of them illuminated by their<br />

flashlights. Even more stars are visible in the sky, as the<br />

increasing darkness of the evening throws the light sources into<br />

even sharper relief. Some of the people seem to pair off,<br />

assisting each other in their unknown quest, while others remain<br />

alone, content to investigate their own little patch of earth. What<br />

are they looking for? We don’t know, and no narrative information<br />

is forthcoming.<br />

3

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

It’s a formal game, while also being, of course, a documentary of<br />

sorts, and the mixture of the two modes is where much of the<br />

interest lies. As in her films Double Tide and Goshogaoka, Eventide<br />

is a carefully choreographed performance piece (one could argue<br />

that it’s actually a direct synthesis of these two prior works) that<br />

gestures toward chance operations even as it’s, in actuality, a<br />

document of predetermined movements. The surface simplicity<br />

— a group of people wander about as dusk becomes dark —<br />

belies the precision of Lockhart’s decision-making. But the<br />

emphasis on time, that inalienable filmic element so frequently<br />

diminished and quashed by narrative allows for all manner of<br />

Balsom’s “wayward drift.” One is free to pay more or less<br />

attention to any part of the image at any given moment, so much<br />

so that viewers might not notice how bright the stars have<br />

become or that one or more of the figures have momentarily<br />

been obscured by the brush. In some sense, it even becomes<br />

Tati-like, inasmuch as Noël Burch recognized that the deep focus<br />

photography of Playtime allowed viewers to focus on only one<br />

part of the image at any given moment. For all its static<br />

austerity, then, Eventide is ultimately an entirely invigorating<br />

experience. — DANIEL GORMAN<br />

ALLENSWORTH<br />

James Benning<br />

“Since moving from 16mm to digital nearly fifteen years ago,<br />

James Benning’s films have become more and more stringent,<br />

foregoing surface incident in favor of intensive examination of<br />

the outside world. The freedom to make the films he wants,<br />

whenever and wherever he wants, has led to a profound<br />

paring-down of cinematic language in which fixed-frame<br />

images of mostly non human subjects — landscapes, buildings,<br />

trains — are offered to the viewer for minutes at a time. By<br />

temporalizing space in this manner, Benning’s films seem to<br />

ask us to look beyond the placid surface of these shots, and to<br />

consider the unseen social relations that brought them into<br />

being, as well as the power structures that keep them in<br />

place… Even by Benning’s minimalist standards, his new film<br />

Allensworth addresses the viewer with a radically reduced<br />

palette.” — MICHAEL SICINSKI [Originally published as part of<br />

InRO’s Berlinale 2023 coverage.]<br />

LABERINT SEQUENCES<br />

Blake Williams<br />

At times, Laberint Sequences, the new short film by Blake<br />

Williams, feels a bit like an experimental feature, despite being<br />

only 20 minutes long. That's because the artist packs a lot of<br />

material in a relatively small space, introducing several visual<br />

ideas and subjecting them to systematic yet unanticipated<br />

permutations. The film was mostly shot at Barcelona's Parque del<br />

Laberint d'Horta, a Neoclassical garden space that contains a<br />

large hedge maze. After beginning with a stereoscopic image of<br />

the garden, Williams provides a number of isolated views of the<br />

space, including plants and trees, a canal with fountains, and a<br />

work of classicist statuary. We also see several shots of a<br />

reflecting pool at the center of the labyrinth, with a few tourists<br />

milling about, including a couple of kids running through the<br />

space. This series of shots, like the entire film, is presented in<br />

anaglyph 3D, so in a way, Williams is both offering the viewer the<br />

basic lay of the land as well as getting us accustomed to the<br />

multi-planar depth of the 3D, and how it accentuates certain<br />

attributes of the garden while flattening others.<br />

At this point, things start getting a bit raucous. Situating his<br />

camera at various angles of the hedges, and then panning back<br />

and forth, Williams uses the moving frame to reconfigure the<br />

visual space, the labyrinth forming solid masses that swivel<br />

across the image. Of course, we expect that we might get "lost"<br />

inside the hedge maze, but this camera movement doesn't<br />

correspond to how any human would navigate the space. Instead,<br />

it is as though the space is shifting around us (and the<br />

occasionally still-visible humans inside). Establishing shots with<br />

a stationary camera keep giving way to these kinetic passages,<br />

which are all the more dramatic because of the use of 3D. After<br />

some digital manipulation of the image -- perhaps a callback to<br />

certain motifs in Williams’ feature film PROTOTYPE -- we begin to<br />

see shots looking up through the trees. At this point, aerial cable<br />

cars make their first appearance, first traversing the screen,<br />

then offering birds-eye views of the garden, and then finally a<br />

few shots from inside the moving car.<br />

Following some brief pans inside an empty room overlooking the<br />

woods (with expansive, Mies-style windows and parquet flooring),<br />

Laberint Sequences includes shots from an old movie, in which<br />

4

CINÉMA DU RÉEL<br />

two women are trying to find their way through a hedge maze in<br />

the dark by candlelight. We see scan lines that suggest Williams<br />

is filming off the television monitor, and eventually, he shows us<br />

earlier scenes from the Laberint with a similar televisual<br />

abstraction. But in between, we see shots of Deragh Campbell, in<br />

her role as Audrey Benac from A Woman Escapes, last year’s<br />

feature that Williams co-directed with Burak Çevik and Sofia<br />

Bohdanowicz. Campbell is seated at a laptop watching the film in<br />

question, and, scanning through text on her phone, she speaks<br />

the women's dialogue along with the footage.<br />

Clearly, Laberint Sequences puts the viewer through their paces,<br />

taking a fairly simple idea -- a study of a manicured landscape --<br />

and introducing denser and denser layers of abstraction. From<br />

an homage to the late Michael Snow, and his panning film ,<br />

to a mechanically achieved birds-eye view, to an appropriation<br />

of relevant material from a piece of narrative cinema<br />

("something horizontal," we might say), and finally a performer<br />

subjecting that outside material to critical scrutiny, this film<br />

explores the many ways that a cultural landmark, usually subject<br />

to the tourist's gaze, can be intellectually reorganized through<br />

filmic intervention. And through it all, Laberint Sequences<br />

maintains the hazy, protruding anaglyph 3D, a method that<br />

implies a promise of presence ("like being there") but actually<br />

doubles down on the representational remove. — MICHAEL<br />

SICINSKI<br />

PARADISE<br />

Alexandre Abaturov<br />

While global headlines are presently dominated by Russia’s<br />

ongoing onslaught of imperialist atrocity, Alexander Abaturov’s<br />

Paradise turns its eye to the country’s east, where casual<br />

bureaucratic cruelty fixes the Republic of Sakha’s taiga-dwelling<br />

denizens in perpetual danger. An opening text scrawl offers<br />

specifics: in summer 2021, an extreme heatwave and resulting<br />

drought triggered massive forest fires, and it was decided that in<br />

certain, rural areas, no government-backed firefighting<br />

intervention was needed if the anticipated damages fell short of<br />

the expense to challenge the blazes. It was left to local<br />

inhabitants, then, to fight The Dragon, as the cascading, racing<br />

flames were so dubbed. This opening is immediately followed by<br />

a young girl in the village of Shologon (where the documentary is<br />

ORLANDO, MY POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY<br />

Paul B. Preciado<br />

“Its primary thrust features a number of trans and non-binary<br />

people playing the role of Orlando. Each actor introduces<br />

themself with their own name, but what may initially appear to<br />

be a similar approach to last year’s Encounters entry<br />

Mutzenbacher quickly gives way to a more explicit blurring of<br />

personal narrative and adaptation. Preciado cuts between<br />

talking head interviews with the actors and scenes from the<br />

novel, but actors flow from discussing their own experiences<br />

to speaking as Orlando in the first person, sometimes on the<br />

scale of a sentence, and the scenes of adaptation are shot on<br />

a soundstage, temporally and spatially expanding themselves<br />

beyond the context of the novel into that of filmmaking. This<br />

latter approach is eventually revealed to be self-reflexive in its<br />

self-reflection, as Preciado explicitly compares the trans<br />

experience of gender to a behind the scenes look at<br />

filmmaking.” — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER [Originally published<br />

as part of InRO’s Berlinale 2023 coverage.]<br />

set) attempting to memorize a passage: “Advise me, sacred<br />

mountain. How does one reconcile man?”<br />

It’s a question that is, of course, unanswerable to any satisfying<br />

degree, but one which guides and pervades all of Abaturov’s<br />

observational, largely unstructured (in any conventional sense)<br />

Paradise, the query itself the closest we get to any kind of<br />

statement of intent. Everything is freighted with potential<br />

meaning. What of a government that places financial<br />

consideration above the lives of its citizens, particularly within<br />

this context where 80% of the regions affected by the enacted<br />

policy are dominated by ethnic minorities? What happens to a<br />

community’s collective psychology and identity when survival is a<br />

daily concern, life-and-death stakes rendered a mundanity? How<br />

does one’s notion of futurity reorganize itself around new<br />

realities?<br />

To the degree that Abaturov attempts any answers, he takes care<br />

to do so presentationally rather than discursively. Scenes of<br />

controlled burns, strategically felled trees, and planning sessions<br />

weave with those of wild horses kicking up dust on village<br />

5

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

LAST THINGS<br />

Deborah Stratman<br />

“Though cryptic and eccentric, this is far from Stratman’s most impenetrable work. Much like her previous film, The Illinois<br />

Parables (2016), Last Things frequently reformulates itself, armed with an arsenal of approaches. The movie embodies a variety<br />

of perspectives, from outer space to microscope slides, as Stratman’s images — landscapes, crystal and rock formations,<br />

sketches, spelunking and laboratory footage, celestial satellite imagery, microscopic forms, etc. — collectively embody an<br />

otherworldly thrill. The soundtrack (including pieces by Brian Eno and Okkyung Lee) and sound design (by Stratman herself) are<br />

often glitchy, alien, and sublime. Stratman’s rendition of rocks, in addition, highlights the complexities of their history and<br />

evolutions. She imbues them with a vastness far beyond the dismissal often extended to the inanimate objects.” — RYAN<br />

AKLER-BISHOP [Originally published as part of InRO’s Sundance 2023 coverage.]<br />

streets, the glow of a tablet reflecting on a child’s face, and locals<br />

eating sandwiches on lunch breaks, flames licking at the edges<br />

of their carved-out, temporary haven. Masks are a common<br />

sighting in Paradise as well, the associated suggestions of 2021’s<br />

Covid-era living both thematic companion and refraction of the<br />

community’s looming fiery threat; iconography we’ve internalized<br />

over the 2020s is subtly and powerfully abstracted in its opaque<br />

inclusion here. But no scene or rhetorical throughline is<br />

over-enunciated or saddled with maudlin sentiment, the weight<br />

of the film’s images to be read in the accumulation of spaces<br />

between them.<br />

This careful restraint likewise applies to Abaturov’s approach to<br />

visual construction, which is essential to Paradise’s considerable<br />

power. Thick, ochre-orange smoke clogs the film’s frames, its<br />

backgrounds choked in desaturation. There’s the insinuation of<br />

armageddon in its almost spectral compositions, black ash<br />

peppering the smoldering landscape — more than anything,<br />

Paradise’s visual character recalls the post-apocalyptic,<br />

sci-fi-inflected imagery of the Floria Sigismondi-directed music<br />

video from Sigur Ros’ “Vaka.” But thankfully, there is no needless<br />

aestheticizing here, which would have the effect of cheapening<br />

the very real human concerns inherent — spectacle is never the<br />

strategy or personality here. Abaturov instead keeps his formal<br />

designs humble, trusting in his portrait’s essential power to reach<br />

viewers. In one scene late in the film, a local worker, one of many<br />

in the group, beams, his unruly mustache entirely frozen, tendrils<br />

rigid as they move over his upper lip. There’s melancholy in<br />

Paradise, but as in that indelible image, there’s also a curious joy;<br />

in the land, in each other, and in surviving. The Dragon is still out<br />

out there, uncertainty remains, help may not come. But we smile<br />

our way into tomorrow, as best we can. — LUKE GORHAM<br />

LA BONGA<br />

Sebastán Pinzón Silva & Canela Rayes<br />

Most of La Bonga takes place in darkness; just flashlights serve<br />

as key lights while voices (voiceovers? diegetic?) guide the shaky<br />

frame to an invisible destination. This destination is the titular La<br />

Bonga, a village that exists only in the memories of those who<br />

once lived there in the north Colombian jungle. Now, the villagers<br />

are resettling after years of displacement, and directors<br />

Sebastán Pinzón Silva and Canela Rayes document this nocturnal<br />

trek and celebration.<br />

The film switches between two focal points: a caravan of those<br />

villagers and friends making the return together and a solitary<br />

mother and daughter duo who take a path separated from the<br />

others. Through both groups, Silva and Rayes collect flashes of<br />

stories about old village life and the subsequent expulsion. A man<br />

in a pink Frozen backpack jokes with his friends, while a<br />

53-year-old woman compliments an 82-year-old man on his<br />

endurance, while memories of white people threatening their<br />

lives suddenly surface. Steadily, the film reveals that the villagers<br />

of La Bonga were threatened to leave their homes twenty years<br />

ago, during the Colombian Civil War, as they were seen as assets<br />

of the guerrilla fighters (FARC is never mentioned by name).<br />

Emotional whiplash overwhelms the villagers as they finally<br />

return to the ruins of La Bonga: some buildings, such as the<br />

“recently” built school, still stand while entire homes have<br />

6

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

framed under a massive tree during the first minutes of dawn<br />

such that their long series of shadows gives us an idea of the<br />

size of the village before cutting to individual portraits, usually lit<br />

by flashlight. Another shot frames their lights in the nighttime to<br />

show a series of tiny lights in the distance snaking their way<br />

through the brush of the jungle. And, in the sort of serendipity a<br />

documentarian prays for, the daughter of our duo puts her<br />

flashlight in her umbrella, which then becomes a makeshift<br />

diffuser as they rest and talk. All of these planned, framed shots<br />

work well when showing a group, but La Bonga’s wisdom lies in its<br />

ability to interrupt these beautiful moments with the<br />

improvisatory, cheap DV confessionals so that we can see the<br />

village’s life in the villagers and vice versa. Silva and Rayes show<br />

the history and lives that make up a community; and, though the<br />

houses may no longer stand, and each villager may have<br />

moments in which they wander in solemnity, the party continues<br />

for now. — ZACH LEWIS<br />

GEOGRAPHIES OF SOLITUDE<br />

Jacquelyn Mills<br />

“More so than a narrative disruption, Mills’ experimental<br />

digressions are, in effect, an attempt to probe and reflect the<br />

push and pull at the heart of Lucas’ environmentalism.<br />

Moments like Lucas’ introduction into the film, walking with a<br />

lantern amidst a pitch black sky perforated with stars; at once<br />

wholly a part of the environment, just another gleaming light,<br />

and yet distinct, somehow apart from the natural fabric of the<br />

place and relegated to forever be an observer. The true<br />

solitude of the film's title reveals itself slowly, in the<br />

uncomfortable middle ground that we seem to occupy<br />

somewhere between Mills' gorgeous compositions: the rugged<br />

mosaic of horse skulls and the cloying primary colors of plastic<br />

detritus.” — IGOR FISHMAN [Originally published as part of InRO’s<br />

Sundance 2023 coverage.]<br />

ONLOOKERS<br />

Kimi Takesue<br />

Kimi Takesue’s third feature film is a fraught, respectably<br />

reflexive process in objectification. Utilizing the much ado of the<br />

tourism industry as our subject (through which it extrapolates its<br />

thesis), Onlookers revels in familiar formal intrigues: static,<br />

compositionally-minded cinematography, distanced gazes, and<br />

soundscapes with ambient sensibilities that somehow recall that<br />

great sandbox video game, Roller Coaster Tycoon 3. To find an<br />

easy and important analog for this film, one might turn to a work<br />

such as Sergei Loznitsa’s Austerlitz, insofar as the subject of<br />

tourism orbits and enables anthropological examination. But<br />

where Loznitsa rooted his analysis in the constructs built from<br />

the relationship with one, very specifically formulated space —<br />

where history can play contingent text to the present’s passivity<br />

— Takesue seems disinterested in anything so determined. Her<br />

montage interlaces landscapes, each often occupied by Laotians<br />

or tourists — persons consistently participating in acts religious,<br />

economic, or excursionist. There’s no discrimination between<br />

these acts, no delineated structure that curates an ideological<br />

trajectory; instead, we simply gather the film’s thesis through<br />

motley organization: a reflexivity that contends with the<br />

camera’s foreign objecthood and its creation of everything<br />

before it into a flattened spectacle. Tethering such a structure of<br />

montage to the global tourism industry (not to mention Takesue’s<br />

vantage as an American filmmaker) makes for an exciting<br />

journey that plateaus about 11 minutes in.<br />

Formal introspection quickly becomes an act of stagnation,<br />

repeating with each new image the idea that came before it. The<br />

equivocal character of each shot asserts the character of the<br />

work as cinematic object. Nothing present in any of the rather<br />

immediate and obvious compositions denotes any sense of<br />

texture, lending an anonymity and ephemerality to the<br />

landscapes themselves, as is emphasized through a pacing in<br />

which each cut occurs within the span of 30 seconds: these<br />

static wides are then variants of the same conception. Sure,<br />

there’s intent in that choice, even articulated in the work’s very<br />

synopsis, but of course intentionality isn’t inherently a virtue. If<br />

this ideology of the montage is meant to be an expression of the<br />

ever-present parade of tourism as a neocolonial, parasitic<br />

industry, that’s a fine sentiment, but there’s little of note here<br />

that hasn’t already been contended with over two centuries of<br />

ethnographic image-making. In fact, it seems that Onlookers<br />

could have registered as a work of greater intrigue and affect<br />

were it a photographic project: an album of stills that curate our<br />

gaze, naturally bringing both attention to the ontological (as this<br />

does), the anthropological (as this does), but also to the object of<br />

curation as a historical process of the imagined (which this does<br />

8

CINÉMA DU RÉEL<br />

completely disappeared into the flora and mud. But that doesn’t<br />

stop Maria de los Santos, the leader of the caravan, from guiding<br />

a celebratory procession through the newfound village and<br />

declaring, “Goddamn, tonight I’m getting drunk no matter what!”<br />

before threatening, “Any men who fall asleep tonight will get their<br />

dicks chopped off!” She’s as serious about the ritualistic<br />

cleansing power of the party as others might be by mourning the<br />

memories never made.<br />

La Bonga, though brazenly political and humanistic, also<br />

develops an air of mystery by choosing what not to reveal.<br />

Though the story of the paramilitaries is told from multiple<br />

perspectives (the exact threatening note shown in an insert<br />

shot), the terms of their return are never given. Why did they<br />

return all at once? Where were they initially gathered before<br />

making the caravan? Did the government give them explicit<br />

permission to return, or was it decided communally via a<br />

diasporic WhatsApp group? All questions are rendered<br />

unimportant as the mythic nature of the return, like Odysseus to<br />

Penelope, takes shape. But then there’s a ghostly POV outside the<br />

caravan, and our duo provides a second mystery. Suddenly,<br />

during the first night’s celebration, handheld DV shots lead us<br />

away from the party and back to the abandoned school while a<br />

solitary, mysterious voiceover worries about getting lost, then<br />

reminisces about an old class. Surely, a shot like this comes from<br />

the filmmakers asking the villagers to shoot their own footage,<br />

but this interruption is placed such that it takes us outside any<br />

literal storytelling to simply meditate (drunkenly, hauntingly) on<br />

which memories cannot be reforged. The DV captures shallow<br />

water as flies, attracted to the camera’s solitary light, dart across<br />

the frame like fireworks. Suddenly, another cut, and the village is<br />

framed in a small corner with literal fireworks marking the party<br />

that still rages on.<br />

Though the majority of the film (both long sequences of the trek<br />

and most of the party) is filmed in the dark, Silva and Rayes<br />

consistently plan inventive ways to frame the villagers’<br />

processions. Many wide shots give profiles of the caravan<br />

7

CINÉMA DU RÉEL<br />

not), set within the subjective history of the photograph.<br />

The idea of the “photograph,” in fact, is overtly present<br />

throughout the film, implied and crystallized in the tourists’<br />

cameras wishing to neatly capture these places they visit and<br />

taking these images with them once their vacation comes to a<br />

close. Sound and time, ultimately, offer little here. They are both<br />

under-utilized and sterile, unnecessary for thematic<br />

extrapolation. This is a film that attunes itself to the formal<br />

machinations of familiar work — each year a lauded<br />

observational doc, hyper-focused on localized global trends,<br />

finds its way to some year-end lists and onto esteemed<br />

streaming platforms — and thus culminates in familiar<br />

perspectives and an even more familiar nondescriptness. With<br />

everything here pitched as a signifier of the exact same thing,<br />

and the signified remaining woefully ignorant to the introduced<br />

contexts, Onlookers is a tired echo of polemics long abstracted<br />

into the institutionalized nether. — ZACHARY GOLDKIND<br />

ROCK BOTTOM RISER<br />

Fern Silva<br />

This is a mode (and, more importantly, length) more typical<br />

amongst Fern Silva’s previous ethnographic pieces, but this being<br />

his first foray into feature-length duration, there obviously needs<br />

to be a little more going on to justify the additional 55 minutes.<br />

And there certainly is — including discussions of the colonial<br />

legacy of science, the communal debate around the construction<br />

of a 30-meter telescope on the sacred Mauna Kea mountain, the<br />

controversy surrounding Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson being cast<br />

as King Kamehameha when the actor isn’t an Indigenous<br />

Hawaiian — but none of these various threads are particularly<br />

fleshed-out on their own, as they’re usually thrown together to<br />

convey some nebulous notion of connectivity. — PAUL ATTARD<br />

[Originally published as part of InRO’s Berlinale 2021 coverage.]<br />

9

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

BEING IN A PLACE: A PORTRAIT OF<br />

MARGARET TAIT<br />

Luke Fowler<br />

Luke Fowler’s latest feature film reflects a slight shift in his<br />

creative project, something that might not be immediately<br />

apparent even to longtime admirers of his work. Although he is<br />

an experimental documentarian, Fowler could also be<br />

considered an intellectual historian. His major works have<br />

focused on specific artists and thinkers of the last century,<br />

including psychologist R.D. Laing (2012’s All Divided Selves),<br />

historian E.P. Thomson (The Poor Stockinger, the Luddite<br />

Cropper, and the Deluded Followers of Joanna Southcott, also<br />

2012), electronic composer Martin Bartlett (2017’s<br />

Electro-Pythagorus), and the short film Cézanne (2019). In<br />

each of these cases, Fowler has combined biographical data,<br />

images, and sounds from historically pertinent locations, and<br />

various excerpts from the subjects’ creations and archival<br />

holdings.<br />

The overall impression of Fowler’s films is that the past is a<br />

constellation, a series of objects and moments held together<br />

conceptually but never capable of forming an irrefutable whole.<br />

In that respect, Being In a Place is certainly of a piece with the<br />

director’s previous films. Composed largely of archival<br />

documents and voice recordings of the late Scottish poet and<br />

filmmaker Margaret Tait, the film abjures any simple didactic<br />

impulse, offering up fragments that provide an impressionistic<br />

sense of her creative worldview. However, this film also marks a<br />

turn toward speculative or corrective history, an attempt to<br />

tentatively accomplish something that Tait herself was unable to<br />

do.<br />

As we see from various notes, shot lists, and official letters of<br />

rejection, Tait was planning a project called Heartlandscape, a<br />

featurette in which she would trace a heart shape around<br />

Scotland with her camera. The film would combine Tait’s<br />

interests in nature and landscape cinema with her other primary<br />

tendency: cinematic portraiture. Moving through the land and<br />

encountering the people in it, Tait aimed to produce a kind of<br />

materialist panorama of her homeland. However, Fowler shows<br />

us documents from the Tait archive that show that at least two<br />

British media organizations, the BBC and Channel 4, rejected the<br />

project, essentially stating that the work Tait proposed did not fit<br />

their existing formats.<br />

So although Being In a Place indeed provides a portrait of<br />

Margaret Tait, Fowler is also trying to reconstruct<br />

Heartlandscape, based on the artist’s notes. This effort, however,<br />

is not revealed until the end of the film, and this makes the<br />

viewing experience a bit frustrating. We see Fowler out and about<br />

in the Scottish countryside, shooting people and recording their<br />

voices (although the two never sync up). But the purpose is<br />

unclear; this approach sometimes seems to be to the detriment<br />

of getting a firmer handle on Tait’s work. To be fair, Tait is<br />

probably the most studied and written-about Scottish artist of<br />

the 20 th century, so Fowler may have thought that a more<br />

conventional documentary, or even one more in keeping with his<br />

earlier strategies, would somehow be redundant. But the overall<br />

impact, while always intriguing, is ultimately rather mixed. We<br />

see and hear just enough of Tait to desire more access to her<br />

work and her thinking, and the supplement Fowler provides never<br />

quite coheres. Nevertheless, if Being In a Place encourages more<br />

viewers to seek out Tait’s quite singular films, it’s all for the best.<br />

— MICHAEL SICINSKI<br />

OUR BODY<br />

Claire Simon<br />

One possibility is that the observation of the camera precludes such violations. Though this may be too simplistic a read — even<br />

if Simon had captured such a traumatic moment, it’s almost unimaginable that she would have included it in the film — as well as<br />

an inimitable antidote, it does add to both the film’s emotional and practical heft. Besides functioning as an encouraging artifact<br />

for future patients, which is to say nearly everyone, as the woman who thanks Simon for filming her surgery hopes, it may at<br />

least be able to serve as a more holistic model for a right relationship between doctor and patient.” — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER<br />

[Originally published as part of InRO’s Berlinale 2023 coverage.]<br />

10

CINÉMA DU RÉEL<br />

THE SECRET GARDEN<br />

Nour Ouayda<br />

Abbas Kiarostami’s 2008 film Shirin is constructed entirely of<br />

closeups of faces as spectators react to a film playing in front of<br />

them. But the film they are watching is never actually shown —<br />

it’s alluded to only via snippets of dialogue and sound effects<br />

that transpire entirely offscreen. Playfully idiosyncratic and with<br />

a wry sense of humor, Nour Ouayda’s The Secret Garden fashions<br />

a sci-fi epic in a similar design to Kiarostami’s experiment;<br />

shooting in and around Beirut on what appears to be 16mm film,<br />

The Secret Garden recounts a takeover by plant-like alien<br />

invaders who are encroaching further and further into the city.<br />

But this surprisingly complicated, expansive scope is relayed<br />

only via voiceover narration while accompanied by otherwise<br />

staid documentary images. In other words, a fictional narrative<br />

and non-fiction images butt up against each other in a kind of<br />

amalgamation of the two modes, each informing but also<br />

contrasting the other (not unlike Ben Rivers’ Slow Action, come to<br />

think of it). In the case of The Secret Garden, Ouayda’s images<br />

consist of various plants, trees, shrubs, and flowers, some<br />

growing naturally in the landscape, some bursting through the<br />

concrete sidewalks and brick walls of the city, and still others<br />

potted and hanging from balconies and window sills. Natural light<br />

coupled with the fine film grain of the 16mm gives the patina of<br />

an aged home movie, like an unearthed relic from the<br />

1970s.<br />

Sectioned into eight chapters, the film charts the strange<br />

appearance of and the gradual accumulation of these<br />

11

A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE DARKNESS<br />

Ben Rivers & Ben Russell<br />

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

“In spite of their stylistic idiosyncrasies, both filmmakers strive to reach beyond basic filmic semiology in search of a sort of<br />

transcendental “realism,” a synthesis of modern ethnography and materialist aesthetics — aesthetics that permit film’s physical<br />

attributes (grain, lens flares) their due import. Their collaborative feature, the experimental documentary A Spell to Ward of the<br />

Darkness, is a fascinating blend of their respective methods that simultaneously honors their individuality. The film’s meticulous<br />

three-part structure feels somewhat rigid and predetermined compared to the more exploratory nature of their other work, but<br />

things gradually open up as we follow a nameless character (Robert A.A. Lowe) as he hangs around a neo-hippie Estonian<br />

commune, trudges alone through some remote Finnish wilderness, and fronts a black metal band in a dark and dingy rock club in<br />

Oslo.” — DREW HUNT<br />

“never-before-seen” plants. Shots of vines emerging from drain<br />

pipes and canal walls reinforce the idea of a violent emergence,<br />

while the voiceover narration suggests the intonation of a<br />

breathless news report. “Chapter 2” introduces Camelia and<br />

Nahla, our ostensible protagonists (even though no human<br />

figures are ever seen during the film). But we do hear their<br />

voices via the narration, creating a kind of harmony between<br />

multiple commentators. According to that narration, the two<br />

women have discovered a box filled with notebooks and a map.<br />

One of the notebooks is titled “At the Edge of the City, a Garden,”<br />

and it contains sketches of all the plants that have 'infiltrated'<br />

the city. A woman’s voice reads excerpts from this mysterious<br />

document, which detail a series of extraordinary creatures and<br />

fauna that occupy a space beyond the city. All the while, images<br />

of plants continue to flash across the screen, a diverse array of<br />

nature footage creating an oddly immersive quality.<br />

Ouayda has a talent for casting the familiar as unfamiliar.<br />

Occasionally, as the narration builds to a dramatic beat,<br />

Ouaydawill violently shake the camera or increase the speed of<br />

the editing, rupturing the otherwise lulling quality of the<br />

recitation. Shots of nature eventually give way to a more urban<br />

milieu, broaching the idea that the plants are either being<br />

domesticated by humans or are silently waiting for a moment to<br />

strike. It's a lo-fi War of the Worlds, a fantasy epic conveyed via<br />

the simplest means. Critic Alex Fields has suggested some<br />

deeper readings than mere genre film pastiche — that Beruit is<br />

difficult to divorce from its context as a site of years-long civil<br />

war, and a palpable yearning for a return to beauty (the<br />

transformation of bomb impact craters into flower beds is a key<br />

part of Godard's Notre Musique, and the plight of Sarajevo feels<br />

pertinent here as well). There are hidden depths to this short<br />

film, a lovely and mysterious object that seeks beauty in the<br />

everyday. The world is wonderous, we simply have to look<br />

carefully, and, importantly, differently. — DANIEL GORMAN<br />

SOUVENIR D’ATHÈNES<br />

Jean-Claude Rousseau<br />

Jean-Claude Rousseau may be one of the best-kept secrets in<br />

world cinema. But fortunately, in recent years, the word seems to<br />

be getting out. Although he’s made a number of features, most<br />

prominently his 1995 film The Enclosed Valley and 2021’s A Floating<br />

World, he has been focused on short-form filmmaking for a<br />

while, producing work that operates within a recognizable<br />

vernacular but is at the same time wholly unique. His two films<br />

from last year, Welcome and The Tomb of Kafka, are simple<br />

interior studies that examine the light relationships between<br />

objects in a room and shifting conditions out the window. The<br />

films exhibit a certain kinship with North American structural<br />

film, especially the work of Ernie Gehr and Michael Snow. But<br />

Rousseau’s interest in the seductive aspects of European<br />

classicism also suggests a connection to the films of Jean-Marie<br />

Straub and Robert Beavers.<br />

Rousseau’s latest film, Souvenir d’Athènes, finds the filmmaker<br />

operating in a Straubian mode, but with decidedly Beaversesque<br />

fillips. In the first several shots, we see a young man seated on a<br />

rock, his head in his hands as he looks down. Perhaps he is<br />

reading a book. We see the Parthenon in the distance, imposing<br />

against a mostly clear blue sky. Rousseau provides a number of<br />

shots of the man on the rock, all taken from the same camera<br />

12

TWO RESERVOIRS<br />

An Interview with Léa Mysius<br />

In 2017, Léa Mysius premiered Ava at<br />

Cannes. Her exhilarating directorial debut was a vibrant coming of age<br />

tale, a showcase of filmic bravado presaging her arrival as a thrilling new<br />

cinematic voice. Since then, the French screenwriter/director's talents have been repeatedly called into action with notable<br />

screenwriting collaborations with André Téchiné (Farewell to the Night), Arnaud Desplechin (Oh Mercy!), Jacques Audiard (Paris, <strong>13</strong>th<br />

District), and Clarie Denis (Stars at Noon). Not content to be solely collecting co-writing credits with a who’s who of contemporary<br />

French cinema, Mysius was simultaneously hard at work on her sophomore film, and so her 2022 return to the Croisette featured both<br />

Stars at Noon, her collaboration with Claire Denis in the Main Competition, and The Five Devils, her long-awaited sophomore directorial<br />

effort at the Director’s Fortnight.<br />

The Five Devils is a spirited blend of themes, ideas, and influences, a nervy coming-of-age thriller about a young girl journeying across<br />

time to uncover a secret buried in her mother’s past. Much like Ava, her latest is yet again a showcase of adventurous screenwriting<br />

and confident direction. Now, on the eve of its 2023 U.S. theatrical release (Ava is finally available on Mubi as well), I connected with<br />

Mysius to probe deeper into the film’s dominant themes, its racial subcurrents, the influence of U.S. literature, and the her writing<br />

process, from collaborations with French auteurs to building out her own idiosyncratic worlds and visions.<br />

14

Thinking through your approach to Ava and then coming to<br />

The Five Devils, I was curious what, if anything, might have<br />

changed in the way that you were writing and<br />

conceptualizing these films?<br />

I'd say that whereas Ava was a much more linear film, a much<br />

sunnier film, mostly focused on this one character, [with] The<br />

Five Devils I wanted to find something a bit more complex and<br />

risky, drawing a gallery of characters, and I had a mosaic like<br />

construction of the many layers of both time and dramaturgy<br />

that fed into the script. So really, the film was a bit of a reaction<br />

to Ava.<br />

Does this require a different way of working, in that Ava had<br />

this free flow, whereas here we are seeing a much more<br />

orchestrated, controlled system of interconnected<br />

characters?<br />

I say both films were very controlled, on set at least. But I do<br />

think that with The Five Devils, because it's a much more complex<br />

story, there was a lot of work to do with camera movements for<br />

them. The mise en scène was much, much trickier because we<br />

had to keep it coherent because it was such an exploded<br />

construction, and that's why perhaps it looks like there was a lot<br />

more control in it. I should add that in contrast to Ava, Paul<br />

Gilhaume and myself, what we wanted was to create a lot of<br />

movement to keep the movement going throughout the film, and<br />

movement is very hard to control, so that's maybe perhaps why<br />

there's this sense that it is controlled.<br />

I saw this incredible quote of yours where you said: “My<br />

biggest satisfaction is when filmmakers start to believe they<br />

have written a scene themselves, even though it was me.” I<br />

was curious about the way that you work with some of these<br />

other French auteurs and how that writing differs in<br />

approach to when you're working within your world.<br />

It's a very, very different process. I'd say, I mean, it's the same<br />

job, but it works very differently. The closest I could describe it is<br />

like: I have two reservoirs, one of which is mine, and the other is<br />

for the other directors I write for. And when it's mine, I dig in and<br />

find my own obsessions, desires, my own source material, my<br />

own images, and I feel quite free with it. I don't need to explain it,<br />

I just go ahead and do it. Whereas the other one is very much<br />

the images and the source material of these other writers, and<br />

it's very much seeing the world through their eyes. Personally, I<br />

couldn't film what they're writing, if you see what I mean, and<br />

perhaps that's linked to this French concept of the auteur.<br />

I remember seeing a clip of Samouni Road and there was a<br />

scene in there where a girl covers her eyes and that opens<br />

up this animated world, and the second I saw that I<br />

immediately thought of Ava. Are there moments where there<br />

is this spillover between the two reservoirs?<br />

I mean, I'm not a robot, so there will be things that escape me,<br />

but I try not to put in what is “of me.” So for example, right now<br />

I'm writing something about a couple, and there will be images<br />

from my own bank that will translate into this film, but then<br />

ultimately it's the role of the director. It's up to the director<br />

whether or not to use them, but the barrier between the two is<br />

porous.<br />

Back to your world and your reservoir, you've mentioned that<br />

Vicky's obsession with sense has a link to your past in your<br />

childhood. Are there specific scents that you remember back<br />

from your childhood that have stuck with you from those<br />

days?<br />

Yeah, I'd say both sight and smell were very much senses that I<br />

really sought as a child. And I wonder if it's maybe because I grew<br />

up in the countryside [that] I had this desire to smell everything<br />

around me. And I do think as a sense it's quite maligned by<br />

humans, maybe because there's something a bit animalistic<br />

about it, in contrast to things like hearing, which we often<br />

associate with beautiful things like music. I've just had a<br />

daughter, for example, and I realize how we stimulate children by<br />

showing them images, visually or even orally. But, I, for example,<br />

try and get her to smell things. I want to develop that sense that<br />

we tend to not focus too much once we leave childhood behind.<br />

There's a condition that I find fascinating: synesthesia, when<br />

someone mixes those senses in their mind. So one particular<br />

smell will automatically trigger a color or a sound will trigger a<br />

color and vice versa.<br />

Vicky's sense of smell in her journey in understanding her<br />

15

mother takes up the bulk of the film. But there is another<br />

journey where Vicky is searching for a part of herself, and<br />

we see this idea of race playing into it where she is clinging<br />

to her [white] mother and perhaps pushing away from her<br />

[Black] father. And the racism she encounters contributes to<br />

it. You had previously mentioned the writing of James<br />

Baldwin and Maya Angelou influencing you, and I was curious<br />

to hear you elaborate a little bit more about your thoughts on<br />

that and how that their work inspired you.<br />

Yes, indeed. I mean, it wasn't just [James] Baldwin and Maya<br />

Angelou, but whilst I was writing the script, I was very much<br />

inspired by U.S. literature, even including Jim Harrison or<br />

[Jonathan] Franzen, and I wanted to see how I could use that<br />

inspiration without imposing very U.S.-specific concepts onto<br />

France that would seem completely artificial. It made me think,<br />

how do we talk about race in France, when it's less clear-cut than<br />

it is in the U.S. And in France, there is a lot of racism, but it's<br />

much more insidious, a bit like a poison, and I wanted to tackle it<br />

without making it very explicit, which tends to put people off and<br />

make them very defensive, and make them deny the reality by<br />

feeling that it's too much of a caricature.<br />

So I thought, right, what realistically would be a mixed race<br />

family in the countryside? I thought, well, it's unlikely they're<br />

going to be Americans, so chances are they're going to come<br />

from Senegal. I wanted it to be this family that actually is normal<br />

— there are mixed race families in the countryside in France,<br />

without denying that they also face racism. But instead of<br />

portraying it as very explicit, I wanted to show it more as an<br />

atmosphere, as an oppressive atmosphere, that imbues life in<br />

this village, and that's how I feel is the best way to translate the<br />

racism in France.<br />

I think this mirrors what you had accomplished in Ava, where<br />

there is the constant presence of fascism around the edges.<br />

I had read that you wanted to have your next film have a<br />

more political lean, and I’m curious whether you would make<br />

these politics, which have been in the background,<br />

percolating, if you’re interested in pushing them to the<br />

forefront in your next work?<br />

Yeah, I mean, I'm right in the middle of that process, and it keeps<br />

changing. And the political angle keeps coming back, and it<br />

scares me because it's now becoming a subject matter and I don't<br />

like working with subject matters. I like working with moments,<br />

with storylines, not subjects, and the question I’m grappling with<br />

is how to really talk about society without it becoming the<br />

subject of the film.<br />

To close us off, you ended The Five Devils with “Cuatro<br />

Vientos,” a gorgeous song about the wind coming in, and it<br />

has this mystical quality of equilibrium. Could you talk about<br />

that choice and how it tied into your thought process about<br />

where the film ends?<br />

Yeah, it was actually the DP Paul Gilhaume who found that<br />

specific song, and I think it perfectly embodies the happy open<br />

end that I wanted to have. Because initially there’s a lot of chaos,<br />

and I like the idea that eventually the chaos organizes itself and<br />

we find this balance, which then allows us to find freedom and<br />

love.<br />

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. — INTERVIEW<br />

CONDUCTED BY IGOR FISHMAN<br />

And to go even beyond that, the quest for Vicky to uncover this<br />

past is born out of the weight she carries of things unsaid, the<br />

things that remain unsaid, but not only inside her family, but<br />

within her community and, on a larger scale, her country.<br />

Because when we think of things that are unsaid in France, there<br />

are things like colonialism and racism that we deny, things we<br />

just don't speak openly of. So it's very much a way of linking<br />

those familial taboos with the village and at a larger scale the<br />

country.<br />

16

KICKING THE CANON<br />

UNKNOWN PLEASURES<br />

Jia Zhangke<br />

Since his breakout 1997 film Xiao Wu, Jia Zhangke has emerged as one of the most gifted artists chronicling life in 21st-century China.<br />

Three of his earliest films — Xiao Wu, 2000's Platform, and 2002's Unknown Pleasures, all of which were made outside China's studio<br />

system — form a loose, low-budget trilogy portraying life at the bottom in an emerging superpower. Jia didn't abandon that focus<br />

when he made the leap to bigger budgets and State approval — 20<strong>13</strong>'s A Touch of Sin, for instance, is also unflinching in its social<br />

criticism — but nevertheless, Unknown Pleasures especially captures the crushing ennui of the early 2000s era.<br />

The film follows three disaffected young people as they navigate life in the changing People's Republic. Unlike Platform — a sprawling,<br />

elliptical, and unwieldy reflection on the rapid social changes from the late 1970s to the early '90s — Jia’s succeeding film is a more<br />

concise and decidedly contemporary tale of alienated youth. Xiao Ji (Wu Qiong) is a reckless scoundrel who falls in love with Qiao Qiao<br />

(Zhao Tao), a singer, dancer, and sex worker who performs at promotional events put on by her gangster boyfriend (and pimp) Qiao<br />

San (Li Zhubin). Xiao Ji's best friend, Bin Bin (Zhao Wei Wei), meanwhile, struggles with depression caused by unemployment and the<br />

scorn of his ball-busting mother (Bai Ru), who is a follower of the Falun Gong church.<br />

Xiao Ji and Bin Bin spend most of their time haunting pool halls by day and drowning their depression in nightclubs by night. The loud<br />

techno music, which remixes iconic pieces of Americana such as Dick Dale's surf-rock spin on "Miserlou," signifies the encroaching<br />

Western influence which coincided with the increasing liberalization of China's markets, a development which culminated in the PRC<br />

joining the World Trade Organization. Jia roots Unknown Pleasures in the present by including contemporary news reports flickering<br />

across discolored, bulbous television sets — a group of textile factory workers are seen celebrating the announcement that the 2008<br />

Olympics will be held in Beijing — and a pervasive sense of internet-era detachment, exemplified by a character nonchalantly asking<br />

17

KICKING THE CANON<br />

if the Americans had invaded China again when she hears a loud<br />

explosion destroy the local textile factory.<br />

Arguably, Unknown Pleasures’ portrayal of late-capitalist malaise<br />

could be read, if not as explicitly Marxist, then at least as a<br />

left-wing, anti-capitalist critique of globalization. The nature of<br />

Jia's social criticism, however, is somewhat surprisingly far more<br />

conservative in character. "In Unknown Pleasures, young people<br />

lack discipline," said the filmmaker in the film's production notes.<br />

"They don't have any goals for the future. They refuse all<br />

constraints. They run their own lives and act independently. But<br />

their spirit is not as free." Indeed, the lives of his central trio are<br />

very much defined by the mass media that surrounds them, while<br />

Chinese culture has faded into insignificance. Their search for<br />

freedom has, ironically, presented them with more limitations —<br />

in the words of Neil Young: "And I know we should be free / But<br />

freedom's just a prison to me."<br />

In what is perhaps the film's most interesting aesthetic choice,<br />

Jia sets Unknown Pleasures in a crime-ridden, rubble-littered<br />

wasteland — heightened significantly from Platform's<br />

comparatively less seedy post-industrial setting — a backdrop<br />

that invokes a kind of post-apocalyptic reflection of the spiritual<br />

decay of post-Maoist China that Jia laments. The characters<br />

seek to escape their hopelessness through shallow<br />

hedonism that they mimic from the Western movies and TV<br />

shows that have recently become accessible to them. While<br />

sitting in a restaurant, Xiao Ji, eager to impress Qiao Qiao, tells<br />

her about his vague ambitions as an outlaw while making<br />

reference to Pulp Fiction's opening scene, quoting its dialogue<br />

and pointing his finger (mimicking a gun) at the other customers.<br />

Jia punctuates the scene with a rare moment of overt stylization,<br />

whipping the camera around in a blur to transition the scene to a<br />

nightclub.<br />

This stylization is remarkable because Yu Lik-wai's consumergrade<br />

digital cinematography otherwise radiates pure homemovie<br />

transience, imbuing the film with something more<br />

ephemeral — an object found and observed, rather than<br />

consumed. Unknown Pleasures' musings on the purgatory at the<br />

end of history recall Hou Hsiao-hsien's Millennium Mambo,<br />

released the year before, but Jia's vision of neoliberal<br />

Weltschmerz is a lot bleaker than Hou's. While Millennium Mambo's<br />

Vicky (Shu Qi) addresses the audience from the future of 2011,<br />

implying some form of resolution and development for the adrift<br />

young woman, Jia cuts his sparse narrative short with Bin Bin<br />

being made to sing for the cops who arrested him after a failed<br />

robbery attempt. The last glimpse the audience gets of him is<br />

standing in a police station — lost, humiliated, doomed to<br />

languish in purgatory forever. — FRED BARRETT<br />

18

FILM REVIEWS<br />

DUNGEONS & DRAGONS: HONOR AMONG<br />

THIEVES<br />

Jonathan M. Goldstein & John Francis Daley<br />

There is no winning in Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) — not really.<br />

You can reach the end of a campaign or defeat something very<br />

nasty, or reach the highest level in a book that tells you what the<br />

highest level could be, but if your friends wish to continue, then<br />

you’ll play on. Unlike other games, measurable skill matters not,<br />

and those who wish to boast of their achievements in any<br />

quantifiable vector will be instantly humbled. Nerds may love<br />

their numbers, but here is a nerd-game — an entire nerd<br />

universe, in fact — in which numbers merely represent fate, the<br />

true subject of the game, and cannot be harnessed outside of<br />

Machiavelli’s virtù to meet fortuna. Dutch historian Johan<br />

Huizinga wrote in his classic Homo Ludens that play is the human<br />

activity most generative to what we now call “culture,” and I’d<br />

argue that D&D fulfills the play role for humans who once relied<br />

upon myth, ritual, and war to satisfy the kind of game in which<br />

rules are erected in order to be stretched and broken — so long<br />

as it makes the game more playful. In Catholic Carnival, a fool<br />

king plays royalty to both mock power and justify it; in D&D, a<br />

player may play out any mythic character of their choosing, so<br />

long as the gods (their dungeon master) believe it to be that<br />

holiest of holy qualities: fun. Though fate decides a measly four<br />

on the twenty-sided dice roll, a deus ex machina appears,<br />

rescuing a naïve character from an early grave; or, though a<br />

veteran character is nearly a god, his attempts to destroy a new<br />

player are impossible, as this new player is the curious younger<br />

sibling of the DM, and the veteran is an asshole. In a world run by<br />

spreadsheets, data, and scientific certainty, it feels radical to<br />

return to that most beautiful aspect of being human — the<br />

imagination. This kind of play asks one to don a mask during a<br />

sacred dithyramb and pretend (or, perhaps, to finally understand)<br />

that the world is malleable.<br />

In other words, Dungeons and Dragons offers an alternative to<br />

those who’d demand the world be made into winners and losers<br />

— especially to those who believe they have the numbers to<br />

prove it. To take away this element of holy play is to rob D&D of<br />

its most powerful virtue. But myths must be made and money<br />

must be sought, hence the successful series of novels based in<br />

19

FILM REVIEWS<br />

the Forgotten Realms (D&D’s catchall “world” for its stories and<br />

guidebooks) universe and the new film, Dungeons and Dragons:<br />

Honor Among Thieves. Reduced to a movie, D&D might merely<br />

seem like an ersatz version of Tolkien: quests, monsters,<br />

dragons, riches, and the other derivatives of high fantasy fiction<br />

that entered the nerd realm’s shared imagination in the 20th<br />

century. Honor Among Thieves is certainly that, though its sense<br />

of playfulness lifts it above our large pile of geek fandom<br />

detritus.<br />

The data analysts who comb through the audience surveys at<br />

major Hollywood studios must have a wealth of information on<br />

teenage boys’ preferred protagonists because, once again, the<br />

sarcastic, lovable asshole firmly plants himself in the middle of<br />

every scene such that no moment can go by without the<br />

teenagers’ beloved sarcasm. Thankfully, it’s Chris Pine this time,<br />

and his boyish smile and not-quite-perfect good looks at least<br />

make these quips believable. He plays Edgin, a human who tries<br />

to do good but succumbs to a life of thievery. After his<br />

one-last-heist goes awry, Edgin gathers a band of adventurers to<br />

rescue his daughter and defeat the power-hungry Forge<br />

Fitzwilliam (Hugh Grant), who may simply be a puppet for even<br />

more malevolent forces.<br />

If the narrative beats sound familiar, it’s because the script<br />

doesn’t try to fix anything that isn’t broken. Inside this hero’s<br />

journey narrative lies a series of scenes that either exposit the<br />

realm’s history (excused as “worldbuilding” in fantasy circles) or<br />

dazzle the audience with some pretty impressive Unreal Engine<br />

demos. The former is a somewhat necessary drag, but the latter,<br />

along with the action sequences, carry the film. Unlike a certain<br />

other franchise that likes to keep its productions quarantined to<br />

Atlanta warehouses, Honor Among Thieves was shot on location in<br />

Northern Ireland and Iceland, allowing the lush, varied<br />

landscapes (and a real volcano) to stand in for the Forgotten<br />

Realms. These are the lands that birthed the Poetic Edda and<br />

many other sources that would inspire Richard Wagner’s Der Ring<br />

des Nibelungen, Tolkien’s Silmarillion, and — subsequently —<br />

contemporary fantasy; so it’s nice to have a respectful nod to<br />

these roots before the CGI parades take the frame.<br />

Thankfully, most of the effects help rather than distract from the<br />

action. A speedy scene midway through the film follows Edgin’s<br />

druid teammate, Doric (Sophia Lillis), as she transforms into a<br />

series of animals to infiltrate a castle, spy on the bouncy Grant,<br />

and escape. The camera follows her in a seemingly unbroken<br />

shot as she flies through cracks as a fly, scampers across<br />

soldiers’ feet as a rat, tumbles through a chimney as a bird, and<br />

emerges out of a house as a cat, then a deer. Though the<br />

sequence is nearly entirely animated, the choice to animate this<br />

as a single shot elevates the tension of her escape, while also<br />

announcing a vote of confidence for the effects team in an<br />

effects-heavy movie. Like all entertainment for adolescent boys,<br />

this also features plenty of light beams and explosions, but here,<br />

at least, there’s clearly someone composing them.<br />

“In a way, the Satanic Panic<br />

of the 1980s and ‘90s<br />

surrounding D&D was right<br />

about one thing: it is literally<br />

a form of magic.<br />

Ultimately, Honor Among Thieves settles for a rote sword and<br />

sorcery journey with a bigger budget and a smaller vision than,<br />

say, Albert Pyun’s ‘80s work in similar territory. It stinks of Kevin<br />

Feige, given the shopworn screenplay, jokey “meta” asides that<br />

beat the audience to make fun of itself, and characters reduced<br />

to their roles. But without Disney’s bureaucracy fine-tuning every<br />

detail, directors Jonathan Goldstein and John Francis Daly are<br />

able to deliver the best possible version of the post-Feige<br />

formula. The action scenes are coherent (thanks in no small part<br />

to hiring action movie veteran Michelle Rodriguez to play the role<br />

of the barbarian Holga), audiences are not asked to have an<br />

advanced degree in the IP in order to have an emotional reaction<br />

to carefully timed cameos, and some of the jokes do land. It’s no<br />

Conan the Barbarian, nor is it even comparable to simply playing<br />

a nice D&D session with good friends, but Honor Among Thieves<br />

has a playfulness that its competitors lack.<br />

In a way, the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and ‘90s surrounding<br />

D&D was right about one thing: it is literally a form of magic.<br />

Despite its reputation for attracting socially-inept nerds, the<br />

game only really came alive if a player had a handle on both the<br />

real world and the world conjured within their heads. Huizinga’s<br />

20

FILM REVIEWS<br />

Homo Ludens notes that religious rituals have always worked<br />

according to this logic of play, where improvisatory straddling<br />

between worlds (spiritual, mental, or metaphorical — depending<br />

on your perspective) caused real change in our physical realm.<br />

D&D allows its players to attune to this ancient, limitless play that<br />

grants them the basic yet radical power to imagine the world<br />

differently. At a time in which major studios promise no<br />

alternative to data-driven, audience-tested, demographicmarketed<br />

schlock, it’s a good power to have. — ZACH LEWIS<br />

DIRECTOR: Jonathan M. Goldstein & John Francis Daley; CAST:<br />

Chris Pine, Michelle Rodriguez, Regé-Jean Page, Sophia Lillis;<br />

DISTRIBUTOR: Paramount Pictures; IN THEATERS: March 31;<br />

RUNTIME: 2 hr. 14 min.<br />

ENYS MEN<br />

Mark Jenkin<br />

In Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men, the unnamed protagonist (Mary<br />

Woodvine, in a role mysteriously dubbed “The Volunteer”) sets out<br />

on a mundane, quietly transfixing routine. Her daily tasks include<br />

observing a rare and unnamed cluster of flowers, transcribing<br />

her observations into a logbook, throwing a rock down an<br />

abandoned mineshaft, and rekindling a small petrol generator;<br />

her spare time she occupies with solitude, a book (Robert Allen<br />

and Edward Goldsmith’s A Blueprint for Survival), and a dwindling<br />

supply of tea. The setting, of course, is an equally solitudinous<br />

island off the Cornish coast in Celtic, Southwest England, and the<br />

year 1973, an era of labor strikes, global oil crisis, and domestic<br />

political conflict. These facts aren’t mere trivia: their import<br />

soon becomes clear as the film discloses — through its<br />

apparational and uneasy iconography — its broader<br />

historiographic relevance, inscribing local and national detail<br />

alike into an eerie and bedazzling (if sometimes bewildering)<br />

spectacle of folk horror.<br />

Eerie, perhaps, best describes the manifestations of the<br />