You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

KICKING THE CANON<br />

GANG OF FOUR<br />

Jacques Rivette<br />

It seems safe to say that we’re currently experiencing a remarkable resurgence of interest in Jacques Rivette; long the most<br />

mysterious of all the Nouvelle Vague directors, as well as the least frequently distributed, cinephiles had to rely on old VHS tapes,<br />

bootlegs, and the enthusiastic writings of a few dedicated critics to construct an idea of his tantalizingly just-out-of-reach oeuvre. It’s<br />

almost fitting that Rivette’s work would exist as a kind of specter or phantom, haunting our collective imaginations. But gradually,<br />

Rivette's work has become more and more available, each release requiring a reconfiguring of the whole. Indeed, no major filmmaker<br />

revisits the idea of “phases” or “periods” more than Rivette. Each work exists in tandem with the others, exploring various threads and<br />

tangents that all orbit a few key central obsessions. As Jonathan Rosenbaum has stated, “Every Rivette film has its<br />

Eisenstein/Lang/Hitchcock side <strong>—</strong> an impulse to design and plot, dominate and control <strong>—</strong> and its Renoir/Hawks/Rossellini side: an<br />

impulse to ‘let things go,’ open one’s self up to the play and power of other personalities, and watch what happens.”<br />

1989’s Gang of Four finds Rivette recontextualizing many of the elements found in his work from the ‘70s <strong>—</strong> nebulous conspiracies that<br />

function like a Hitchcockian MacGuffin, a mostly female ensemble, blatantly theatrical settings, and an emphasis on improvisation. But<br />

gone is the 16mm film and bold, borderline psychedelic colors of Celine and Julie, Duelle, and Noroit, replaced with 35mm and the<br />

sharper, slicker cinematography of DP Caroline Champetier (a student of long-time Rivette collaborator William Lubtchansky). The film<br />

oscillates between two primary settings: there is the Parisian acting class led by Constance Dumas (Bulle Ogier), a demanding star of<br />

the stage who frustrates and captivates her students in equal measure, and then there is the suburban home occupied by four of her<br />

students <strong>—</strong> Cecile (Nathalie Richard), Anna (Fejria Deliba), Joyce (Bernadette Giraud), and Claude (Laurence Côte).<br />

1

KICKING THE CANON<br />

After an introductory scene set in one of Constance's classes, the<br />

film cuts to Cecile moving out of the shared living space to move<br />

in with a boyfriend while Lucia (Inês de Medeiros), another acting<br />

student, from Portugal, moves into her now unoccupied room.<br />

After the women settle in, Anna attends a party where she meets<br />

Thomas (Benoît Régent), a gregarious but mysterious man who<br />

offers to drive her home. Things are going well, until Anna<br />

realizes that Thomas already knows the way to the house,<br />

despite the two having never met before, and she demands that<br />

he pull over and drop her off. Thomas gradually becomes<br />

involved with each of the women, ingratiating himself into their<br />

lives under false pretenses while searching for a key left behind<br />

by Cecile. What is the key for? What does it open? And who is<br />

Thomas, really? Rivette teases these questions out for the entire<br />

film, ultimately denying pat resolutions in favor of playful<br />

ambiguity.<br />

The two settings are connected by frequent scenes of a<br />

commuter train coursing through the landscape, a kind of visual<br />

metaphor for the characters moving from one world to the other.<br />

While studying with Constance, the women rehearse scenes from<br />

Marivaux's Double Inconstancy, as well as works from Racine and<br />

Molière. Rivette invites one audience, the viewer, to share space<br />

with another, the audience-within-the film, as we watch these<br />

rehearsals stop, start, repeat, and reconfigure, a constant search<br />

for some abstract concept of “truth” that eludes the women no<br />

matter how hard they try. For her part, Constance seems mostly<br />

unhelpful, her comments cryptic and harsh, occasionally leading<br />

to a student breaking down into tears or storming off the stage.<br />

Throughout all this, Rivette and Champetier move the camera in<br />

a serpentine path, frequently framing the actors on a proscenium<br />

before panning or dollying away to reframe their bodies or<br />

turning 180 degrees to take in the audience in their seats (there<br />

appear to be a dozen or so women in the class, although there<br />

are only ever two on stage at any given moment). Over the course<br />

of the film's generous 160-minute runtime, Rivette indulges in<br />

many such sequences. As he was fond of saying, “the work is<br />

always much more interesting to show than the result.”<br />

Eventually, much of the action moves away from the theatrical<br />

space to focus on Thomas' mysterious designs on the house and<br />

its inhabitants. After trying unsuccessfully to seduce each<br />

woman in turn, he eventually manages to win over Claude, which<br />

allows him unfettered access to the house after their lovemaking<br />

sessions. His search for the key has something to do with Cecile’s<br />

boyfriend, a criminal who may or may not have been set up by<br />

the authorities and whose trial plays out in brief snippets<br />

occasionally glimpsed on the TV or overheard on the radio. Like<br />

many Rivette films, the central mystery here is never fully<br />

explicated; Thomas claims at different points to be a policeman,<br />

a documents forger, and an artist. It will never be made explicit<br />

which one of these identities is true, although it hardly matters.<br />

The house itself is likewise ambiguous, recalling the film-withinthe-film<br />

of Celine and Julie, a haunted space where a peculiar<br />

psychodrama plays out (although Gang of Four is never as playful<br />

or outright comedic as that earlier film).<br />

Throughout the film, notions of playacting and performance spill<br />

over from one space into the other, like a brief segment where<br />

the women stage a mock trial of Cecile’s unseen boyfriend that<br />

plays out like an improv session. Is he really guilty of anything?<br />

We’ll never know, just like we don’t know exactly why Constance<br />

is removed from her class by gruff-looking men who seem to<br />

suspect her of a crime. It’s all acting, a game, an excuse for<br />

Rivette to gather friends and collaborators and riff on a genre.<br />

It’s his complete mastery that makes such a lark so intoxicating<br />

to witness. Ultimately, the presence of the morally dubious<br />

Thomas, a male interloper in an otherwise entirely femalecentric<br />

world, brings the women closer together, cementing their<br />

solidarity. As Mary Wiles writes, when the women rise up against<br />

Thomas to save Cecile, “they retain control of the keys that<br />

unlock their feminine potential and allow them to take control of<br />

their lives and their art.” After Gang of Four, Rivette would return<br />

to the theater after a long absence, as if the film rejuvenated<br />

him. Great art has a way of doing that. <strong>—</strong> DANIEL GORMAN<br />

13<br />

2

FILM REVIEWS<br />

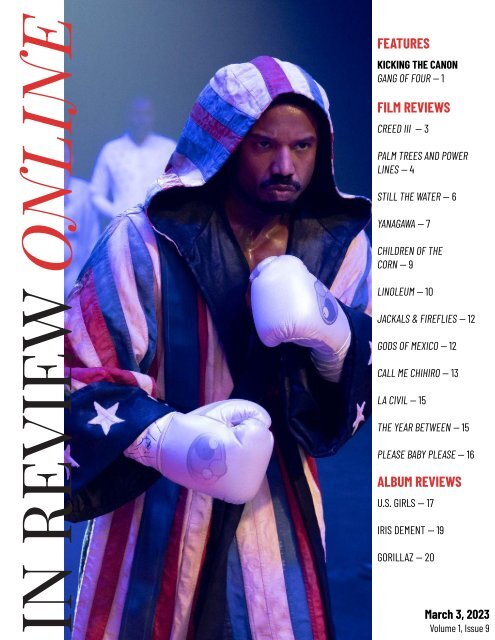

CREED III<br />

Michael B. Jordan<br />

Creed III continues to mirror the trajectory of its parent Rocky<br />

franchise. The first one was a dare-you-say transcendent<br />

recapitulation of the original film’s working-class inspirational<br />

sports story about a young (and this time Black) man coming to<br />

understand his own political capital. Creed II tossed most of that<br />

aside: our hero Adonis (Michael B. Jordan), like Rocky Balboa<br />

before him, became merely the arrogant champion, this while the<br />

much more interesting story of his opponent got pushed to the<br />

background. Now, with this third entry, we get closer to Rocky III,<br />

in which the complacent hero must fight someone who has a<br />

legitimate beef to battle for so that he can maintain his<br />

masculine pride.<br />

Adonis is flourishing in retirement from fighting. He’s rich and<br />

successful, his family is thriving; his wife Bianca (Tessa<br />

Thompson) is a renowned music producer, and his daughter<br />

Amara (Mila Davis-Kent) wants to take up boxing. But out of<br />

Adonis’ past comes an old face, that of Damian Anderson<br />

(Jonathan Majors), a childhood friend who took the fall for an act<br />

of violence committed when they were teenagers and has been<br />

in prison for 18 years. Originally the more promising fighter,<br />

Damian has only honed both his skills and his anger in the joint,<br />

and now he wants Adonis to get him a title match out of the gate.<br />

You’d think Adonis would turn to mentor Rocky for a little advice<br />

here, but pretty much any mention of Sylvester Stallone’s<br />

character has been conspicuously scrubbed here for whatever<br />

reason. In any case, it’s not long before some suspicious<br />

circumstances give Damian exactly the opportunity he demands,<br />

and when he unsurprisingly finds himself champion, his larger<br />

agenda of revenge snaps into view for Adonis, even though the<br />

audience could have smelled it from a mile off. Adonis will, of<br />

course, eventually have to come out of retirement to fight him,<br />

and the movie sets about its bland trajectory of explaining how<br />

violence doesn’t solve anything, except when it does.<br />

17 3

FILM REVIEWS<br />

It’s a banal choice made even emptier by being contrasted with<br />

Adonis’ domestic concerns. Bianca has been even further<br />

reduced to a merely worried spouse, occasionally one who warns<br />

that her husband's values are a little out of whack. Daughter<br />

Amara is violently lashing out at school (against a smarmy bully<br />

who absolutely deserves it, but whatever), and we’re to waffle<br />

about whether or not she needs to learn to defend herself. These<br />

are all moot questions; we’re watching a fucking boxing movie.<br />

The central conflict of enmity between the two leads falls apart<br />

here: Damian has had his life stolen from him, either by Adonis’<br />

negligence or by a terrible carceral system, and he’s got a<br />

completely reasonable argument. Adonis feels guilty, but<br />

dismisses Damian’s anger. Whether or not either fighter wins in<br />

the end, the emotional conflict is unresolvable in the ring, except,<br />

spoiler alert, the two men eventually make up after the bout for<br />

no discernible reason.<br />

“There’s so much richness to<br />

the world [of] the Creed<br />

franchise that it’s increasingly<br />

disappointing to see those<br />

aspects… get pushed aside.<br />

Setting narrative aside, though, the most novel element here is<br />

that star Jordan has taken over the directing gig. It’s largely a<br />

competent job. Although he doesn’t do much to elevate the<br />

formal work in the dramatic scenes, it’s clear that he’s spent a lot<br />

of time with his performers. Majors brings a really fearsome<br />

aggression to the role, as well as wearing his intense self-pity<br />

almost like a second skin. He’s a remarkable actor, and he’s doing<br />

quite fine work here. But it’s in the boxing sequences that Jordan<br />

has made some interesting choices. The fights boast a distinct<br />

emphasis on technique and speed. They may not be the elegant<br />

long takes that occasioned the first Creed, but there’s a ferocity<br />

on display here that’s both refreshing and appropriate to the<br />

story.<br />

As these movies go forward, they look more and more like the<br />

generic entries in the franchise they’re spun off from, and maybe<br />

that’s okay; nobody ever got too mad at the Rockys for being<br />

run-of-the-mill crowd-pleasers. But there’s so much richness to<br />

the world depicted in the Creed franchise, so much available to<br />

dissect about Black masculinity, class distinctions, racial<br />

conflicts, capitalism, on and on, that it’s increasingly<br />

disappointing to see those aspects <strong>—</strong> which were so present<br />

initially <strong>—</strong> get pushed aside. <strong>—</strong> MATT LYNCH<br />

DIRECTOR: Michael B. Jordan; CAST: Michael B. Jordan, Tessa<br />

Thompson, Jonathan Majors, Phylicia Rashad; DISTRIBUTOR:<br />

United Artists; IN THEATERS: March 3; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 56 min.<br />

PALM TREES AND POWER LINES<br />

Jamie Dack<br />

When Jamie Dack’s Palm Trees and Power Lines premiered at last<br />

year’s Sundance Film Festival, it was against the backdrop of a<br />

roiling and mostly insufferable online debate about “age gap,”<br />

coinciding with social media discovering P.T. Anderson’s Licorice<br />

Pizza. That film famously features a romantic, albeit nonsexual,<br />

entanglement between a preternaturally self-assured 15-year-old<br />

boy and a driftless woman in her twenties, presented largely in a<br />

comedic, judgment-free context. Unlikely to suffer the same<br />

levels of “discourse,” Palm Trees and Power Lines also depicts a<br />

relationship between a high school student and an adult, but the<br />

tone is unmistakably more fraught. It treats the problematic<br />

nature of the coupling as the basic premise, even while touching<br />

the third rail of dramatizing statutory rape. The film takes its<br />

characters, as well as the viewer, to some extraordinarily dark<br />

places, acknowledging the predatory underpinnings of the<br />

relationship, before concluding on a note as quietly despairing as<br />

any film in recent memory. But what truly chills the blood here is<br />

how the film presents an adolescent in a going-nowhere<br />

situation, wrapping up her entire sense of self-worth in the<br />

affections of an older man, and how readily he wields kindness<br />

and the attention she’s starved for at home to break her spirit<br />

and bind her to him.<br />

We meet 17-year-old Lea (newcomer Lily McInerny) in the final<br />

weeks of summer break before the start of her senior year.<br />

Living with her divorcée mother (Gretchen Mol) in an anonymous<br />

southern California suburb, Lea spends her days laying out in the<br />

sun, playing on her phone, and killing time hanging out with her<br />

shiftless friends. Without overplaying the drudgery, the film does<br />

an effective job of presenting Lea’s life as an ambitionless blur of<br />

4

FILM REVIEWS<br />

casual drinking, awkward backseat hookups <strong>—</strong> the film makes a<br />

point of showing that Lea’s already sexually active before we<br />

jump into the story proper <strong>—</strong> and teenage malaise, exacerbated<br />

by mom bringing home a new guy seemingly every night. After a<br />

failed attempt at a dine and dash, Lea is saved by Tom (Jonathan<br />

Tucker), a 34-year-old diner patron claiming to be a private<br />

contractor, who intervenes on her behalf. What follows is a<br />

courtship that, under different circumstances, could be<br />

considered endearingly chaste. Tom drives her home and seems<br />

genuinely curious about her interests. She calls him up when<br />

she’s frustrated by her home life, and they talk about her hopes<br />

and dreams while watching airplanes landing at the airport late<br />

at night from the bed of his pickup truck. In contrast to the<br />

teenage boys she’s accustomed to, primarily treating her as a<br />

sexual plaything, Tom has the confidence to take things slowly;<br />

asking for permission before kissing her and even allowing Lea to<br />

play the role of aggressor. For Lea, Tom represents escape: an<br />

adult she has all to herself whose quiet intensity comes across<br />

as guileless and romantic; someone who says things to her like<br />

how she’s “not like any girl I know” and “you see me, and I can<br />

really see you.” He talks about taking her away from the<br />

monotony of her life and always looking after her. For a young<br />

woman desperate to feel special and have someone devoted to<br />

them, it’s easy to understand how she looks past the blinking red<br />

warning lights (his secretiveness, his lack of concern about their<br />

age difference, those rumors of other young women) that keep<br />

cropping up.<br />

The term “grooming” has become so thoroughly misappropriated<br />

and devalued by the political right that it’s now all the more<br />

bracing to see the act in its true, legitimately insidious form.<br />

Although only months away from adulthood, Lea, with her large<br />

expressive eyes, stringy build, and girlish demeanor, reads on<br />

screen as considerably younger (McInerny herself is in her early<br />

twenties), and her desperation to please Tom is easily<br />

weaponized against her. It’s not simply his increased and<br />

decidedly less tender sexual appetites <strong>—</strong> which she haltingly<br />

acquiesces to <strong>—</strong> but also his possessiveness and tendency to say<br />

things like, “you’re never gonna leave me, because nobody loves<br />

you the way that I love you.” There is an ulterior motive to Tom’s<br />

generosity, and it culminates in an especially upsetting<br />

fifteen-minute-long sequence in a hotel room, where the nature<br />

of Tom’s business interests become all too clear. Filmed with<br />

clinical detachment, including a locked-down, five-minute take<br />

filmed from across the small room where Lea is forced to make<br />

small talk with a middle-aged john, we can all but observe her<br />

soul attempting to escape her body as she surrenders herself<br />

sexually while the man she loves waits outside in the hallway,<br />

preventing her escape. It’s unsettling less for the act itself <strong>—</strong><br />

Dack’s camera angles are respectful and restrained, emphasizing<br />

Lea’s disengagement as she focuses on a smoke detector on the<br />

wall until the act mercifully concludes <strong>—</strong> than for how Lea is<br />

forced to smile through a strained meal afterwards with Tom,<br />

now laid bare as a glorified pimp, pretending everything’s great<br />

while silently she’s dying on the inside.<br />

5

FILM REVIEWS<br />

It’s the kind of performance from Tucker that could adversely<br />

cling to an actor; devoid of any showiness or affectations that<br />

easily signal to the audience that he’s only playing a bad guy. He<br />

merely inhabits someone who’s a monster, skillfully breaking<br />

down Lea’s defenses and exploiting her vulnerabilities, never<br />

betraying his calm and in-control demeanor. The film follows his<br />

lead, eschewing dramatic fireworks and direct confrontations for<br />

understated observations of unguarded moments. It doesn't play<br />

like a traditional cautionary tale or a challenge that’s been<br />

overcome by its young protagonist. Rather, it’s altogether more<br />

sticky and perceptive about the lasting psychological damage<br />

that’s been visited upon Lea. What lingers is the realization of<br />

just how deeply Tom’s claws have been sunk into her, laying the<br />

groundwork for a potential lifetime of codependency and<br />

subjugation. There’s real integrity in the choices that Dack and<br />

co-writer Audrey Findlay have made here, particularly in carving<br />

out a path for hope and liberation while still acknowledging the<br />

gravitational pull of the abyss. <strong>—</strong> ANDREW DIGNAN<br />

DIRECTOR: Jamie Dack; CAST: Lily McInerny, Gretchen Mol,<br />

Jonathan Tucker; DISTRIBUTOR: Momentum Pictures; IN<br />

THEATERS & STREAMING: March 3; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 50 min.<br />

STILL THE WATER<br />

Naomi Kawase<br />

Naomi Kawase's 2014 romance drama Still the Water is never<br />

short on striking imagery. Set in Amami Ôshima, an island off the<br />

southern coast of the Japanese mainland, the film is overflowing<br />

with beautiful shots of crashing waves, misty mountains, and<br />

painterly sunsets. A particularly memorable sequence early on<br />

also captures main character Kyôko (Jun Yoshinga) diving along<br />

the lush seabed which surrounds the island, clad in her schoolgirl<br />

uniform. Kawase briefly suspends her in a twilight world between<br />

dream and reality, her underwater odyssey veering into the<br />

fantastical before she ultimately comes up for air, breaking the<br />

spell. When it comes to setting a mood, Kawase succeeds<br />

handsomely.<br />

Narrative and character are another story. Described by Kawase<br />

herself as her "masterpiece," ahead of its premiere at the 2014<br />

Cannes Film Festival <strong>—</strong> "There is nothing I want more than the<br />

Palme d'Or," she explained. "I have my eyes on nothing else." <strong>—</strong><br />

Still the Water plods along for two uneventful, dreary, and<br />

pompous hours. The characters don't converse as much as they<br />

6

FILM REVIEWS<br />

spout pseudo-philosophical questions at each other. "Why is it<br />

that people are born and die?" wonders Kyôko after telling her<br />

love interest, the mercurial Kaito (Nijiro Murakami), about her<br />

shaman mother Isa's (Miyuki Matsuda) terminal illness, the exact<br />

nature of which isn't disclosed.<br />

Kawase's preoccupations have not changed all that much since<br />

she chronicled life, love, and death in a rural community with her<br />

1997 feature directorial debut, Suzaku <strong>—</strong> a film far more<br />

deserving of being called a masterpiece, for whatever that’s<br />

worth. Instead of letting Still the Water’s story unfurl organically in<br />

front of her documentarian's gaze, the filmmaker strains to<br />

imbue every scene with meaning and a quotable, faux-deep line.<br />

A possible explanation for this: Kawase had, by this point, been<br />

nominated for the Palme d'Or a total of three times, so perhaps<br />

her naked ambition just got the better of her.<br />

“Instead of letting Still the<br />

Water’s story unfurl<br />

organically… [Kawase}<br />

strains to imbue every<br />

scene with meaning and a<br />

quotable, faux-deep line.<br />

With its countless scenes accompanied by arpeggiated piano<br />

tinkering, Still the Water seems cynically designed to appeal to a<br />

more sentimental segment of the arthouse crowd. One would<br />

expect a director as accomplished as Kawase to somehow<br />

complicate the maudlin tale of young love, but the impact of the<br />

crime thriller-esque appearance of a dead body evaporates<br />

almost immediately, as the film puts it on the back burner. And<br />

even though Kaito's trip to Tokyo to visit his father (Jun<br />

Murakami, Nijiro Murakami's real-life father) introduces a<br />

welcome change of pace <strong>—</strong> the film finally feels unpretentious<br />

and natural <strong>—</strong> Kawase can't help but cap off the sweet father-son<br />

bonding moment with a labored monologue on fate, delivered by<br />

the father who seems to shroud his bitterness over the divorce<br />

with Kaito's mother in New Age philosophy.<br />

Kyôko regularly turns to the eccentric fisherman Kamejiro (Fujio<br />

Tokita) for advice, his habit of espousing kooky ideas, which the<br />

film more or less treats as gospel, offering comfort to the young<br />

girl as she struggles to come to terms with her mother's<br />

imminent death. Meanwhile, Isa, whose illness can only be<br />

described as being the mother of a headstrong teenager in a sad<br />

coming-of-age story-itis, spends most of the film in bed,<br />

regurgitating whatever well-worn ideas she picked up from the<br />

chief shaman.<br />

Although Still the Water's natural beauty is unimpeachable,<br />

Kawase opts to juxtapose the island's scenery with not one but<br />

two scenes of goats being slaughtered, both having their throats<br />

cut by a straight razor. It's difficult to verify the authenticity of<br />

these scenes but they are framed as part of the island's<br />

traditional rituals, so in light of Kawase's semi-documentary<br />

approach and cultural differences with regards to the treatment<br />

of animals, their inclusion <strong>—</strong> real or not <strong>—</strong> can perhaps be<br />

forgiven. What's harder to forgive is how the film tries to offset<br />

its overbearing dullness with hollow philosophical musings, in the<br />

process wasting both star Jun Yoshinga <strong>—</strong> who makes the most<br />

of the turgid script <strong>—</strong> and cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki's<br />

considerable talents. <strong>—</strong> FRED BARRETT<br />

DIRECTOR: Naomi Kawase; CAST: Nijirô Murakami, Jun<br />

Yoshinaga, Miyuki Matsuda; DISTRIBUTOR: Film Movement; IN<br />

THEATERS & STREAMING: March 3; RUNTIME: 2 hr. 1 min.<br />

YANAGAWA<br />

Zhang Lu<br />

Zhang Lu has proved a unique presence in 21st-century film: A<br />

Korean-Chinese literary intellectual of the 1980s who became a<br />

little-known cult figure in the outsider DV movement in 2000s<br />

China, he then defected to South Korea at the exact moment that<br />

wave began to terminally recede. Over the 2010s, Zhang gradually<br />

moved to the fore of the Korean indie scene, and just at the<br />

moment the Korean wave was peaking in the Western world, he<br />

defected again, at first to Japan and ultimately back to China,<br />

even as growing political hostility to China in the West is<br />

manifesting as cultural isolationism. His newly released <strong>—</strong> in the<br />

West, anyway <strong>—</strong> Yanagawa represents the pivotal point of that<br />

last transition, but it’s anything but a digression. Superficially, the<br />

film heavily parallels Zhang’s preceding feature, Fukuoka; both<br />

follow yearnful, middle-aged East Asian intellectuals as they<br />

journey to Northern Kyushu in search of lost love. It would be<br />

7

FILM REVIEWS<br />

easy to posit a hackneyed thesis like "Zhang is saying 'x' about<br />

inter-Asian social dynamics," but his work operates on a more<br />

nuanced register than that, one concerned with the way complex<br />

intercultural dynamics subtly influence the already knotted web<br />

of interpersonal relationships. Characters are universally<br />

allegorical rather than avatars of nations or class. The dual<br />

settings of Beijing and Yanagawa are triangulated with<br />

occasional reference to the distant, unseen apex of London.<br />

Consider how Zhang’s 2005 feature debut, Tang Poetry,<br />

contrasted a direct, imagistic, raw depiction of emptiness and<br />

domestic violence with the elliptical textual density of the<br />

medium that film took as its titular subject.<br />

In Yanagawa, the audience finds themselves at the other<br />

extremity of the relational spectrum: complete unity. Every<br />

image is steeped in text; there is no shot that does not center a<br />

character, just as there is no text that is semiotically distinct<br />

within a composition. Every image in the film is in an unusual<br />

aesthetic harmony with the moment that meets it. The editorial<br />

grammar is understated and appropriately punctuated. The<br />

cinematography is subtly obfuscatory and tightly bound by rules,<br />

as is the meandering but dramatically austere story. We see<br />

people using their phones but never what is on them. Characters<br />

act with a deliberateness so overwrought as to be<br />

indistinguishable from reckless impulse. Despite a cultivated<br />

artifice of "realism," the dialogue is often bizarre and<br />

non-naturalistic, each line a functional hook in a continuity of<br />

poetic logic. For example: in the opening sequence, central<br />

character Dong (Zhang Liuyi) tells a complete stranger that he<br />

has been diagnosed with stage-four cancer in a bizarre and<br />

unempathetic exchange, but for the rest of the film, he obscures<br />

this fact from the people he loves most, to his own detriment.<br />

Each textual construct in Yanagawa functions this way, as irony,<br />

or as contrast, or as disconnect, compounding loops of meaning<br />

within loops of feeling. Cumulatively the effect is novelistic in the<br />

best way possible, building a metatextual schema in the viewer’s<br />

mind as the film progresses, a nebula of intrigue and implication<br />

demanding analysis from its audience. Zhang is like an ambient<br />

narrativist, reveling in minute textural shifts in feeling and affect,<br />

and maintaining intrigue and a subtle aesthetic build across<br />

duration. On a more tangible level, Yanagawa's mournful longing<br />

is relatable to anyone who has experienced the sad misdirects of<br />

love, without seeking to reflect common experiences back at its<br />

audience. <strong>—</strong> NOEL OAKSHOT<br />

DIRECTOR: Zhang Lu; CAST: Ni Ni, Zhang Liuyi, Xin Baiqing;<br />

DISTRIBUTOR: Film Movement; STREAMING: February 24;<br />

RUNTIME: 1 hr. 52 min.<br />

8

FILM REVIEWS<br />

CHILDREN OF THE CORN<br />

Kurt Wimmer<br />

Kurt Wimmer's mirthfully overwrought Children of the Corn, a<br />

revamp of one of horror's longest and least-consequential<br />

franchises, is more fun than it should be. It's not a good movie <strong>—</strong><br />

did you expect it to be? <strong>—</strong> but Wimmer, who wrote and directed,<br />

carves up a breezy, playfully lurid, never boring slab of sinister<br />

silliness, a welcome reprieve from the surfeit of dour, traumaobsessed<br />

horror films that A24 produces and has inspired, selling<br />

self-seriousness as art. Wimmer made his name with Equilibrium,<br />

one of the more endearing post-Matrix dystopian action flicks of<br />

the early 2000s, directed with a glut of style, some of which is<br />

pretty cool; its unwinking approach to a ludicrous concept offers<br />

unintentional laughs, especially when Christian Bale thinks he's<br />

giving a great performance, but a laugh is a laugh, and Wimmer<br />

really believes in the material. Certainly no one can deride him<br />

for laziness. He followed this up with Ultraviolet, a flamboyant<br />

swirl of CG shine and action scenes so absurd they almost pass<br />

as surreal. It's a mess, and often resembles a PlayStation video<br />

game, but there are some images that spark with inspiration.<br />

Wimmer has been quiet for years, and his involvement with a film<br />

no one was clamoring for provoked little hype. Children of the<br />

Corn premiered in 2020, then lingered in limbo for three years;<br />

it's only making its way to theaters now, and it won't stay long.<br />

Instead, it’s as a surprise bit of pulpy pleasure tucked snuggly<br />

between disposable slashers and accepted classics on Shudder<br />

that the film will find life. A small town of destitute farmers<br />

gathers for a town hall meeting, vexed over their failed crops and<br />

demanding a remedy. The government is willing to pay the<br />

denizens to not plant corn, and everyone goes along with the<br />

idea <strong>—</strong> well, except the kids, who are led by the unhinged Eden<br />

(Kate Moyer) in a craven crusade to save the corn by killing their<br />

parents. But the real impetus for the slaughter is that the police,<br />

trying to save a group of 15 students from a hostage situation<br />

(which we never see), accidentally gas and kill the kids. They<br />

have to pay. Meanwhile, a teenager who will soon be escaping her<br />

dead town to go to college (Elena Kampouris, who was 22 when<br />

this was made) tries to stop them, but you almost root against<br />

her because the iniquity of the killer kids is handled so joyfully.<br />

The disturbing story revels in the expression of evil, and so do<br />

you.<br />

9

FILM REVIEWS<br />

The digital photography looks lovely, belying the modest budget<br />

<strong>—</strong> lustrous light splashing over flaxen fields that sway prettily in<br />

the wind, vast grids of golden grain reticulated in orderly files<br />

under the blue sprawl of sky. The camera moves rambunctiously,<br />

and Wimmer oscillates between intrusive close-ups and<br />

slow-motion shots of children traipsing in eerie unison or<br />

marching minaciously through night-darkened streets, armed<br />

with axes and picks and hoes and pitchforks. Some fun images:<br />

the lead little girl, garbed in a gas mask as gray whorls of smoke<br />

writhe all around her and a collection of captured adults beg for<br />

mercy; and the pint-sized psychos sitting behind the wheels of a<br />

pack of big yellow bulldozers, like slumbering beasts, that growl<br />

to life and slowly close in on their prey who are cowering in a<br />

ditch, waves of dirt washing over them. There's also an insert<br />

shot of the camera whirling with an almost Bay-esque bombast<br />

around a water tower as the sun breathes brightly behind the<br />

time-tarnished structure, a familiar image that succinctly says:<br />

"Rural America." Why include this shot? Because it's fun. Is it a<br />

well-placed, meaningful moment? Not really. But it’s obvious that<br />

Wimmer is trying to keep things lively.<br />

The problem, then, is that there's no innocence to corrupt here <strong>—</strong><br />

our main villain is menacing from the beginning, and we don't<br />

ever see how she influenced a whole town of rural children to<br />

rise up and slaughter the adults. The diabolical deity they serve,<br />

He Who Walks Behind the Rows in King's story and the original<br />

film, makes no notable impression (not that it did in any previous<br />

iteration), its presence depicted as poorly-animated tendrils<br />

wriggling in the rows. Wimmer's film isn't particularly memorable,<br />

and the Children of the Corn series has yet to summon a single<br />

indelible moment in 40 years, but you have to appreciate a horror<br />

film that aspires to entertain, and often succeeds. Good job, Kurt,<br />

and welcome back.<br />

The problem, then, is that there's no innocence to corrupt here <strong>—</strong><br />

our main villain is menacing from the beginning, and we don't<br />

ever see how she influenced a whole town of rural children to<br />

rise up and slaughter the adults. The diabolical deity they serve,<br />

He Who Walks Behind the Rows in King's story and the original<br />

film, makes no notable impression (not that it did in any previous<br />

iteration), its presence depicted as poorly-animated tendrils<br />

wriggling in the rows. Wimmer's film isn't particularly memorable,<br />

and the Children of the Corn series has yet to summon a single<br />

indelible moment in 40 years, but you have to appreciate a<br />

horror film that aspires to entertain, and often succeeds. Good<br />

job, Kurt, and welcome back. <strong>—</strong> GREG CWIK<br />

DIRECTOR: Kurt Wimmer; CAST: Elena Kampouris, Kate Moyer,<br />

Callan Mulvey; DISTRIBUTOR: RLJE Films; IN THEATERS: March<br />

3; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 32 min.<br />

LINOLEUM<br />

Colin West<br />

These days it feels like we’re more frequently encountering<br />

stories of people <strong>—</strong> particularly men <strong>—</strong> obsessed with legacy.<br />

Characters yearn for a sense of permanence while us viewers,<br />

overwhelmed by the high-speed, haphazard contentification of<br />

everything, silently wish for something more solid in our lives<br />

too. One temporarily pacifying pleasure is to reminisce, letting<br />

memory launch us back to our recollection of earlier, simpler<br />

days when so much seemed to be ahead of us and the world<br />

wasn’t so complicated. Colin West’s new feature Linoleum is made<br />

in this spirit. It jettisons the ruminative self-seriousness a more<br />

prestige-inflected drama might opt for, instead preferring a<br />

snug, pleasantly offbeat vibe that’s equally nostalgic and<br />

sanguine.<br />

Cameron Edwin (Jim Gaffigan) is the host of a shoestring-budget<br />

children’s science show on local TV (think a failing, super-retro<br />

Bill Nye the Science Guy). His milquetoast life gets upended when<br />

a space-race-era satellite crash lands in his backyard, inspiring<br />

Cameron to MacGyver a rocket ship in his garage in a bid to fulfill<br />

his long-held dream of becoming an astronaut. His wife Erin<br />

(Rhea Seehorn) and daughter Nora (Katelyn Nacon) already think<br />

he’s losing it a bit, and as their family faces mounting turmoil,<br />

strange disruptions to his life begin to convince him that there’s<br />

more to his reality than he thought.<br />

You’d be forgiven if the first thing that comes to mind when<br />

watching Linoleum is “Kaufman-lite.” Much of the film’s style and<br />

themes are derivative of Charlie Kaufman’s work <strong>—</strong> the neurotic<br />

handwringing about mortality, the surrealist touches bending the<br />

story world’s contours, the doses of metaphysics providing the<br />

springboard into questions of the meaning of life. There’s even an<br />

implied minor thread around gender identity concerning Marc<br />

10

FILM REVIEWS<br />

JACKALS & FIREFLIES<br />

Charlie Kaufman<br />

Depending on your disposition, New York City’s claustrophobic<br />

crush of humanity is either unsettling or liberating, if not both<br />

simultaneously <strong>—</strong> it’s not easy to find your foothold in a place<br />

where crying in public is both a rite of passage and a punchline.<br />

There are many, many love letters to New York City out there, but<br />

Charlie Kafuman’s Jackals & Fireflies is less a declaration of<br />

devotion than a wistful, extended Missed Connection. An<br />

unnamed narrator, played with gentle gravitas by the poet Eva<br />

H.D., crisscrosses the city in an unspecified time frame, noting or<br />

forging fragments of connection amidst the buffeting streams of<br />

urban ambiance. In keeping with Kaufman’s surrealist<br />

sensibilities, Jackals & Fireflies is a meandering tone poem<br />

whose only other major character is the city itself.<br />

H.D., who wrote the 20-minute film’s script, most recently<br />

collaborated with Kaufman by penning the poem “bonedog” for<br />

I’m Thinking of Ending Things. Like fellow flaneur Leopold Bloom,<br />

who wanders through Dublin in equally mesmerizing fashion,<br />

H.D.’s narration is a loose amalgamation of stream of<br />

consciousness and internal monologue, peppered with wry<br />

observation and personal reflection. Cinematographer Chayse<br />

Irvin (Blonde and BlacKkKlansman) shot the film with a Samsung<br />

Galaxy S22 Ultra as part of a new campaign, but unlike<br />

high-budget shot-on-iPhone features, Jackals & Fireflies retains<br />

a down-to-earth moodiness that befits its pensive subject. Even<br />

in the face of solitude, there’s more than a little serendipity; it’s<br />

their fleeting coexistence that Kaufman, in his own understated<br />

way, chooses to celebrate. <strong>—</strong> SELINA LEE<br />

DIRECTOR: Charlie Kaufman; CAST: Eva H.D.; DISTRIBUTOR: <strong>—</strong>;<br />

STREAMING: February 12; RUNTIME: 20 min.<br />

GODS OF MEXICO<br />

Helmut Dosantos<br />

Helmut Dosantos’ feature debut, Gods of Mexico, is an ethereal<br />

work of observation, informing tonality through compositional<br />

rigor, the beauty on display siphoned into a controlled stasis. In<br />

opposition to historical narratives of modernization and the<br />

industrial imperialism that ravages the landscapes of indigenous<br />

communities, Dosantos seeks an immobility that dignifies itself<br />

through the act of statis-as-resistance. He frames a collection of<br />

indigenous peoples in a plethora of tableaux so that, when<br />

brought together, they might construct a new perception and<br />

narrative of resilience. But this well-meaning survey of beauty<br />

and might quickly collapses into the ornamental.<br />

At a point, the film’s stillness and observation becomes rote, its<br />

capacity to evoke its ideas and aestheticized vision begins to<br />

stifle, and the whole thing pretty openly flails toward<br />

ethnographic gaze. One might be able to extrapolate intention in<br />

invoking beauty as a faculty of the very representation it<br />

expresses, but there isn’t enough of a sense of subjectivity as the<br />

camera’s inherent estrangement seriously affects our perception.<br />

These people become objects of a leering gaze, one that flirts in<br />

spectacle and only affirms that the indigenous subjects are<br />

being made fetish. A black-and-white portraiture motif adopted<br />

during the film’s mid-section reads as grotesquely projected<br />

nostalgia, seeking to render those images of history as specters<br />

within a reimagining of this process, wherein their ghosts are<br />

caught in that quest for an image. These forms, if<br />

reappropriated, offer little new but a pointed reflexivity. In the<br />

portraits, we see figures ripped from their storied landscapes<br />

and placed on display.<br />

The intent is clear enough: of seeking reclamation of these<br />

historied images through a context of labor and inserting <strong>—</strong> and<br />

12

FILM REVIEWS<br />

bringing to the foreground <strong>—</strong> a textured proximity to the land.<br />

However, even those images read as fraught: austere and<br />

enclosing, orchestrated to such rigid compositions that it’s<br />

difficult to know whether each act was sincere or only performed<br />

as to amplify a sensorium, as so much of the film is less<br />

interested in a people and their ways and more transfixed by the<br />

capacity one has to curate that. It all feels quite removed from<br />

the humanity the film ostensibly seeks to capture, and is instead<br />

more alike the very violence desired to be here subverted. And<br />

the structural integrity God of Mexico’s narrative hinges on is of<br />

such simplistic juxtaposition that the only real affects that land<br />

are sensory pleasures of kinetic compositions, aural texture, or<br />

the evocative qualities of a well-lit frame. Sadly, these few truly<br />

beautiful frames are burdened by their utter passivity.<br />

“[God of Mexico’s] wellmeaning<br />

survey of beauty and<br />

might quickly collapses into<br />

the ornamental.<br />

The end credits are overlaid with a track that can only be<br />

described as a blatant Philip Glass riff, concluding this 90-minute<br />

montage with that a sense of grandeur especially not<br />

appropriate for this subject matter. The Qatsi trilogy works so<br />

well with Glass’ music because it dehumanizes its subjects<br />

purposefully, creating charged spectacle as to extrapolate from<br />

each image an impression, then molding these elusive materials<br />

into a monolithic concept, enveloped by poetic montage. To bring<br />

this kind of gaze to these communities, reducing them to<br />

idealisms, feels like a betrayal: an orchestration that turns their<br />

willing participation into the very kind of aesthetic structure<br />

once actively used to objectify them.<br />

The specific Indigenous communities represented in the film are<br />

as follows: the Aztec (or Nahua), Chinantec, Cora, Cucapa,<br />

Guarijio, Huave, Ikoot, Maya (and Lacandon), Mazatec, Mexicanero,<br />

Mixe, Mixtec, Purepecha, Raramuri, Tepehuan, Tohono O’odhaim,<br />

Totonac, Yaqui, and Zapotec peoples. These distinct indigenous<br />

cultures have been swallowed up into the homogenizing vision of<br />

Gods of Mexico; it reflects a curious<br />

hypocrisy, as the director made this film as “a wake-up call about<br />

the importance of preserving such cultural diversity against a<br />

world that wants us more and more homogeneous.” Why then are<br />

these disparate indigenous communities observed through a lens<br />

that perceives them as all alike? In fairness, it would be in bad<br />

faith to suggest that the intention here is as corrosive as the<br />

final project comes across <strong>—</strong> the intent obviously was not to<br />

present these portraits as mere echoes of colonial gazes. But<br />

when working in this mode of baroque polish and Euro<br />

aestheticism, there’s little else to take away. <strong>—</strong> ZACHARY<br />

GOLDKIND<br />

DIRECTOR: Helmut Dosantos; CAST: <strong>—</strong>; DISTRIBUTOR:<br />

Oscilloscope Laboratories; IN THEATERS: March 3; RUNTIME: 1<br />

hr. 37 min.<br />

CALL ME CHIHIRO<br />

Rikiya Imaizumi<br />

From its first frames, Rikiya Imaizumi's Call Me Chihiro is easily<br />

identifiable as a Netflix original. Adapted from Hiroyuki Yasuda's<br />

manga Chihiro-san, the film's flat, textureless cinematography<br />

and crisp digital sheen carry the signifiers associated with the<br />

kind of streaming dross that any discerning cinephile would<br />

avoid like the plague. Content-wise, the film doesn't appear to<br />

fare any better: main character Chihiro (Kasumi Arimura) is a<br />

former sex worker with a naturally sunny disposition. Widely<br />

beloved, she brightens people's day while working at a bento<br />

shop, pets a stray kitten, and even feeds, bathes, and clothes a<br />

homeless man (Keiichi Suzuki) <strong>—</strong> all within the first ten minutes<br />

no less.<br />

The sleepy seaside town she lives in is home to a number of<br />

kooky characters like Okaji (Hana Toyoshima), a teenager who<br />

spends her free time stalking Chihiro, taking pictures of the<br />

young woman, clearly enthralled. The sage Chihiro, meanwhile,<br />

turns out to be aware of this, playfully confronting Okaji when<br />

she finally works up the courage to speak to her. Moments like<br />

this reveal Call Me Chihiro's biggest problem: its protagonist is a<br />

bit of a goody two-shoes. Instead of being alarmed by Okaji's<br />

stalking, she recognizes the girl's social alienation and forms a<br />

maternal bond with the bespectacled teen. Even when a<br />

foul-mouthed young boy's mean-spirited prank culminates in him<br />

13

FILM REVIEWS<br />

stabbing her in the arm with a pen, she takes it in stride,<br />

offering to buy the boy a hamburger bento and doling out a very<br />

pedagogically progressive punishment which consists of light<br />

teasing and asking him to apologize. Of course, the boy, Makoto<br />

(Tetta Shimada), warms up to her pretty much immediately.<br />

The largely plotless drama's relaxed pace feels appropriate given<br />

its setting, and the stakes are suitably low. Anything resembling<br />

conflict usually comes in the form of mundane<br />

misunderstandings or conflicting desires <strong>—</strong> a single mother<br />

reprimanding someone for making her look bad in front of her<br />

neighbors, a young girl not wanting to go on a family trip <strong>—</strong> and it<br />

takes a good while before Call Me Chihiro delves into its titular<br />

character's somewhat turbulent inner life. Although the script<br />

doesn't always do her a lot of favors, Arimuri imbues the<br />

superficially flawless Chihiro with some rough edges, especially<br />

once the film finally decides to foreground her loneliness and<br />

lingering grief from her mother's death, while never allowing her<br />

to be anything other than unfailingly kind and understanding.<br />

The reveal that her chipper energy obscures a more mournful<br />

side isn't exactly a surprise, as any attentive viewer will likely be<br />

able to piece together that her ability to bring joy and comfort to<br />

so many stems from her own rather isolated life, her habit of<br />

neglecting herself while constantly being concerned for others<br />

becoming clear relatively early on. When she comes across the<br />

dead body of the homeless man she had previously taken care of,<br />

she is alone in her grief, choosing not to share her tragic find<br />

with anyone. As there is no one to inform of his death, she ends<br />

up burying him herself, before returning to her lonely apartment<br />

to sullenly wash the dirt off her skin.<br />

Quietly melancholy sequences like these are what make<br />

Imaizumi's latest more memorable than most of what currently<br />

clogs the digital arteries of streaming platforms <strong>—</strong> this goes<br />

double for Netflix, whose library is overstuffed with beige,<br />

throwaway content fodder that seems to have been conceived by<br />

an AI <strong>—</strong> and its reflections on loneliness and the value of strong<br />

communities and found family do, to a generous viewer at least,<br />

carry shades of Hideaki Anno's 2000 arthouse romance Ritual<br />

and Satoshi Kon's 2003 animated comedy-drama Tokyo<br />

Godfathers. This isn't to say that Call Me Chihiro comes anywhere<br />

close in terms artistic value <strong>—</strong> or excitement for that matter <strong>—</strong><br />

but as far as Netflix originals go, one could do a lot worse than<br />

this warm-hearted, empathetic, and yes, occasionally uneventful<br />

and saccharine slice-of-life drama. <strong>—</strong> FRED BARRETT<br />

DIRECTOR: Rikiya Imaizumi; CAST: Kasumi Arimura, Hana<br />

Toyoshima, Ryuya Wakaba; DISTRIBUTOR: Netflix; STREAMING:<br />

February 23; RUNTIME: 2 hr. 11 min.<br />

14

FILM REVIEWS<br />

OLD REVIEWS NEW RELEASES<br />

LA CIVIL<br />

Teodora Mihai<br />

“The goal is to keep focus on empathizing with Cielo, but raises a<br />

vital question: who gets to look away? Cielo, like her inspiration,<br />

doesn’t, having no choice but to stare straight ahead. But we the<br />

viewers and the outsider director can instead safely watch<br />

violence reflected in the eyes and heard in the gasps of the<br />

troubled woman to whom the camera so tightly clings. The line<br />

between empathy and pity is sometimes blurred by the remove<br />

from Cielo’s perspective. If there’s anything keeping La Civil on<br />

the right side of that line, it’s Ramírez’s performance, which<br />

conveys bottled rage and frustration without ever boiling over<br />

into melodrama… suffused with complicated, sometimes<br />

conflicting emotion.” <strong>—</strong> CHRIS MELLO<br />

DIRECTOR: Teodora Mihai; CAST: Arcelio Ramírez, Álvaro<br />

Guerrero, Jorge A. Jimenez, Ayelén Muzo; DISTRIBUTOR:<br />

Zeitgeist Films; IN THEATERS: March 3; RUNTIME: 2 hr. 20 min.<br />

THE YEAR BETWEEN<br />

Alex Heller<br />

“The Year Between has no interest in painting Clemence in a<br />

particularly flattering light, her disaffected nature and constant<br />

putdowns established from the very first frame. It’s quite obvious<br />

that Heller, a bipolar filmmaker herself, wants to craft a<br />

warts-and-all portrait of mental illness, one that refuses to<br />

sugarcoat its devastating effects. And while such an approach is<br />

respectable, it also makes Clemence quite unpleasant company,<br />

as Heller errs on the side of real more than some audience<br />

members might be willing to tolerate. There’s never any doubt<br />

that such an approach is intentional, and the fact that it leaves<br />

Clemence nearly impossible to empathize with makes for a<br />

rather fascinating dichotomy.” <strong>—</strong> STEVEN WARNER<br />

DIRECTOR: Alex Heller; CAST: Steve Buscemi, J Cameron Smith,<br />

Wyatt Oleff; DISTRIBUTOR: IFC Films; IN THEATERS: March 3;<br />

RUNTIME: 1 hr. 23 min.<br />

15<br />

16

FILM REVIEWS<br />

PLEASE BABY PLEASE<br />

Amanda Kramer<br />

“It’s the rare film that proves capable of achieving genuine novelty, and even rarer to find one that manages to parlay novelty alone<br />

into success. Too many such aspirants resort to gauche gimmickry or conceptually florid moonshots that result only in scaled-up<br />

failures. On its face, it might seem strange to observe this when talking about Amanda Kramer’s Please Baby Please, a film not just<br />

indebted to but intentionally cribbing from a number of aesthetic and modal reference points. But if every story tells a story that has<br />

already been told, it follows that recreation is creation. Given the thematic and discursive well it’s drawing from, it’s not surprising that<br />

at the core of the film’s singular makeup is a profound sense of the familiar, but in taking pains to defamiliarize these recognizable<br />

parts before carefully recomposing them, Please Baby Please proves to be like few other films you’re likely to have seen.” <strong>—</strong> LUKE<br />

GORHAM<br />

DIRECTOR: Amanda Kramer; CAST: Andrea Riseborough, Harry Melling, Demi Moore; DISTRIBUTOR: Music Box Films; IN THEATERS:<br />

March 3; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 35 min.<br />

16

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

BLESS THIS MESS<br />

U.S. Girls<br />

Meghan Remy, mastermind behind the<br />

experimental pop project U.S. Girls, has<br />

been on a trajectory of constant evolution<br />

since she began releasing music under her<br />

deceptive moniker in 2008. On Bless This<br />

Mess, the Chicago-born singer-songwriter<br />

dives into an elaborate fantasia<br />

constructed through retro, dance-flavored<br />

pop, with the therapeutic vulnerability of<br />

2020's Heavy Light and the dark emotional<br />

complexity of 2018's In a Poem Unlimited<br />

seeming like blurry memories <strong>—</strong><br />

sufficiently worked through and left in a<br />

less-than-pleasant past.<br />

Remy opens Bless This Mess with the<br />

glutinous disco groove of "Only Daedalus,"<br />

where she finds herself trapped in the<br />

labyrinth constructed by the titular<br />

mythological architect who also happens<br />

to be a particularly controlling lover: "You<br />

can't invent my love / And you can't hide<br />

me away." Unimpressed with his creation,<br />

she quips, "You're good with your hands /<br />

But where's your soul?" before segueing<br />

into a cool chorus where she reminds her<br />

partner that "under the street there is a<br />

beach," a line repurposed from a May 68<br />

slogan which, at the time, was regularly<br />

spray-painted throughout France.<br />

Throughout, this new, more outwardly<br />

exuberant emotional register shimmers<br />

with the danceable, luxuriously<br />

throw-back sheen of contemporary pop<br />

music, exemplified by the likes of<br />

Beyoncé and Dua Lipa, whose last albums<br />

appropriated the sounds blaring out of<br />

discothèques in the '70s and '80s. "Tux<br />

(Your Body Fills Me, Boo)," for instance, is<br />

a funky goofball ditty in which Remy<br />

takes on the POV of a frustrated tuxedo,<br />

sick of wasting away in its owner's closet.<br />

The track is the record's indisputable<br />

highlight, Remy firing on all cylinders<br />

while still sneaking in some sly, if not<br />

exactly novel, social commentary: "I was<br />

your passport to so many rooms / Your<br />

mask of pure exclusivity / Now you treat<br />

me like a long gone novelty / A costume, is<br />

that how you see me?"<br />

The only drawback to the track's<br />

explosive flurry of synthesizers,<br />

handclaps, vocoded backing vocals, and<br />

absurdly humorous lyrics is that it<br />

completely overshadows the rest of the<br />

LP. The more subdued "R.I.P Roy G. Biv"<br />

follows "Tux" and tries its hand at a<br />

similar brand of whimsy, relaying a<br />

17

fantasy tale of a rainbow paramour, "Roy G.<br />

Biv" referencing the acronym for the hues<br />

that make up a rainbow. Unfortunately,<br />

Remy and guest vocalist Marker Staling fail<br />

to pull off the tune's silly central metaphor,<br />

an act made nearly impossible by the<br />

track's plodding pace.<br />

Similarly, "Futures Bet" opens, intriguingly<br />

enough, with thick, distorted guitar chords<br />

and a riff which, for reasons unclear,<br />

plays the first few notes of "The<br />

Star-Spangled Banner," but it quickly falls<br />

apart amidst an aimless, bland melody<br />

and trite lyrical truisms like, "When<br />

nothing is wrong / Everything is fine / This<br />

is just life" <strong>—</strong> shockingly uninspired<br />

toss-off, especially considering the<br />

gorgeous, challenging work Remy is<br />

capable of creating. It's true: nothing on<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

Bless This Mess reaches the depth of, say,<br />

"M.A.H.," a track which provocatively took<br />

on Obama's drone warfare and public<br />

image <strong>—</strong> "As you were the first in line to<br />

use those bugs up high / The coward's<br />

weapon of choice / But you got that<br />

winner's smile / And you know how to<br />

leave 'em moist" <strong>—</strong> but balanced its<br />

incendiary politics with a varied sonic<br />

architecture, Remy making use of an<br />

arcade of different textures and<br />

instruments.By contrast, Bless This Mess<br />

<strong>—</strong> an uncharacteristically "Live, Laugh,<br />

Love"-esque album title for the<br />

songwriter <strong>—</strong> feels less diverse than<br />

slightly disjointed. The penultimate<br />

"Pump" <strong>—</strong> a reference to breast pumps,<br />

Remy having recently given birth to twins<br />

<strong>—</strong> starts promisingly, with a steady<br />

electro pulse propelling the song into its<br />

first verse. But the song's eye-rolling<br />

wordplay <strong>—</strong> "My first child was two /<br />

Talking 'bout two babies at once" <strong>—</strong>quickly<br />

puts a damper on the cut's otherwise<br />

elegantly assembled nu-disco swagger.<br />

The pivot into spoken word on the<br />

prophetically-titled "Outro (The Let<br />

Down)" ends things on a whimper, as<br />

Remy spells out the album's already<br />

clearly articulated themes in a thuddingly<br />

literal manner.<br />

The last few years have seen pop music,<br />

and a sizable amount of supposedly<br />

alternative music as well, become<br />

obsessed with producing "bangers" <strong>—</strong><br />

hook-filled, club-ready, singable, vaguely<br />

empowering <strong>—</strong> often at the cost of sonic<br />

and thematic intricacy, so perhaps<br />

seeing this turn for the prosaic isn't<br />

exactly surprising. It's a shame, though,<br />

because whenever Bless This Mess<br />

unshackles itself from the demands of<br />

18

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

contemporary pop aesthetics, it offers<br />

plenty of playfulness, weird ideas, and<br />

infectious melodies. But too often, Remy's<br />

natural songwriting talent gets bogged<br />

down by her incessant need to sound<br />

timely, something which her previous<br />

work never seemed all that concerned<br />

with. One hopes that this isn't the<br />

beginning of Remy's descent into the<br />

musical ghetto of algorithm pop <strong>—</strong> if<br />

nothing else, Bless This Mess' best<br />

moments prove that she is way too good<br />

for that. <strong>—</strong> FRED BARRETT<br />

LABEL: 4AD; RELEASE DATE: February 24<br />

WORKIN’ ON A WORLD<br />

Iris DeMent<br />

Iris DeMent likes to play the long game.<br />

When the Pentecostal-raised but avowedly<br />

agnostic 31-year-old from Kansas City,<br />

Missouri, made her John Prine-cosigned<br />

debut on the alt-country/Americana<br />

stage, she opened her first album, 1992’s<br />

Infamous Angel, with a succinctly perfect<br />

verse that laid the foundation for a<br />

career-spanning concept of secular<br />

spirituality: “Everybody is a wonderin'<br />

what and where they all came from /<br />

Everybody is a worryin' 'bout where they're<br />

gonna go when the whole thing's done /<br />

But no one knows for certain and so it's all<br />

the same to me / I think I'll just let the<br />

mystery be.”<br />

On “Workin’ on a World,” the title track and<br />

opener off DeMent’s new album, the<br />

philosophical tables are turned: Now it’s<br />

DeMent who’s “filled with sadness, fear,<br />

and dread.” But instead of retreating<br />

inward, she finds faith in the cause of<br />

others, and decides it’s actually what<br />

comes after that’s more important than<br />

the troubles of the day. “I'm workin' on a<br />

world / I may never see,” goes the<br />

plainspoken chorus, which sets the tone<br />

of this set as surely as “Let the Mystery<br />

Be” did her diaristic debut. That is to say<br />

that DeMent has put herself on a path of<br />

activism <strong>—</strong> and not for the first time,<br />

either. In 1996, just before the longest gap<br />

in her discography, she released The Way<br />

I Should, an album which grappled with<br />

the turbulent political climate of its day.<br />

And both the biggest swings and the<br />

modest misses of this set largely trace<br />

back to that effort.<br />

At its best, DeMent’s activism not only<br />

hits its targets with a sneering<br />

righteousness, but also puts the rock<br />

back in what’s long been a defanged<br />

alt-country genre. The first few seconds<br />

of “Workin’ on a World” feature the same<br />

old-timey church piano that DeMent<br />

19

made the foundation of her austere 2012<br />

album, Sing the Delta, but here that<br />

instrument is quickly interrupted by a hard<br />

symbol crash and a full band<br />

accompaniment joining in, with a rollicking<br />

Mark Knopler-style guitar solo in the<br />

middle and a horn section worthy of<br />

Muscle Shoals. It’s a statement of purpose<br />

in more ways than one, but the specific<br />

motivations for its call-to-arms are<br />

sketched in vague terms.<br />

DeMent saves the proper nouns and a<br />

litany of causes that she’s fighting for (and<br />

against) with this album for its<br />

eight-minute second track, “Going Down to<br />

Sing in Texas.” That song <strong>—</strong> penned after<br />

DeMent was shocked to arrive at a Texas<br />

university campus where she’d long<br />

performed only to see a new sign<br />

posted about proper etiquette for open<br />

carry <strong>—</strong> splits the difference between<br />

ragtime gospel and jazz shuffle, and<br />

recalls some of the more distended late<br />

Bob Dylan compositions. Though, unlike<br />

Dylan, DeMent is less interested in weaving<br />

puckish Americana myths than soberly<br />

addressing the people who inspire her to<br />

stand her ground (The Chicks [née Dixie],<br />

the Squad, Muslims) and calling out some<br />

familiar groups of offenders (war<br />

criminals, greedy people, Trump). It’s an<br />

ambitious piece that sometimes trips over<br />

the corniness of its good intentions (“I got<br />

a plan / How about we ban hate from every<br />

corner of this land?”), much like 1996’s<br />

“Wasteland of the Free” did when it took a<br />

moralizing tone against a generation that<br />

knew “the name of every crotch on MTV.”<br />

But the careening focus proves<br />

instructive, and is born out over the course<br />

of an album whose breadth is nothing<br />

short of disarming.<br />

The best song here, “The Sacred Now,”<br />

not only rocks the hardest, but features<br />

some of DeMent’s sharpest and most<br />

economical writing in decades, an<br />

effortless string of evocative<br />

juxtapositions lent a kind of cosmic grace<br />

through the singer’s see-sawing vocal<br />

delivery: “Time speeds by, then slows<br />

down / All is lost, hope is found.” DeMent<br />

was at the vanguard of a new intellectual<br />

movement in country music in the ‘90s,<br />

and songs like “The Sacred Now” and “The<br />

Cherry Orchard” <strong>—</strong> which feels out the<br />

psychological contours of a character<br />

from the Chekhov play of the same name<br />

<strong>—</strong> remind just how singular her<br />

songwriting voice (to say nothing of her<br />

uniquely rural-influenced trill) has always<br />

been. On “Nothin’ for Dead,” which<br />

features more horn charts and gorgeous<br />

pedal steel, DeMent gets especially<br />

adventurous, sketching a series of short<br />

observational vignettes with loosely<br />

extracted life lessons, before inserting<br />

herself into the song to comment directly<br />

on its jumble of ideas.<br />

In fact, the fulcrum of a lot of these<br />

songs <strong>—</strong> the motif that holds together an<br />

album that often seems to be pushing in<br />

a lot of different directions at once <strong>—</strong><br />

tends to be a verse, or even just a few<br />

lines, where DeMent reflects on her own<br />

charge as an artist and as a moral<br />

person. Toward the end of “Going Down to<br />

Texas,” she returns to the subject of an<br />

afterlife, but it’s suddenly become a lot<br />

more real to her, maybe because of that<br />

inevitable proximity to guns: “I don’t know<br />

if there’s a judgment day or a master plan<br />

/ But I know I want to be ready if before<br />

the Lord I stand.” The collected<br />

sentiments of Workin on a World, from its<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

most earnest moments of liberal guilt to<br />

its poetic discursiveness, amount to a<br />

mighty testament, a simultaneous<br />

retrospective look at DeMent’s<br />

career-long preoccupations as<br />

songwriter and a building-out of her<br />

earnest concern for the future. <strong>—</strong> SAM C.<br />

MAC<br />

LABEL: Flariella; RELEASE DATE:<br />

February 24<br />

CRACKER ISLAND<br />

Gorillaz<br />

“It’s a cracked-screen world,” sings Damon<br />

Albarn on Cracker Island, the eighth<br />

studio album from everyone’s favorite<br />

cartoon band. Since 2001, Damon Albarn<br />

and Jamie Hewlett have used their<br />

Gorillaz project to hold a carnival mirror<br />

up to society. The universe they’ve built is<br />

wild, dark, and wacky, distorting the art<br />

and politics of our own world into a 20+<br />

year party playlist for the end times.<br />

When life gets rough, human beings find<br />

freedom on the dance floor <strong>—</strong> this is<br />

something Damon Albarn understands<br />

instinctively. “Are we the last living<br />

souls?... Get up!” Albarn sang back on<br />

2005’s Demon Days, and Cracker Island is<br />

its creators’ latest groovy reflection on<br />

our insane modern world.<br />

Albarn has enjoyed a career most artists<br />

can only dream of. The story is the stuff<br />

of legend at this point: after bearing the<br />

standard for the Britpop generation as<br />

the frontman of Blur, Albarn went<br />

left-field <strong>—</strong> teaming up with comic book<br />

artist Jamie Hewlett to create the world’s<br />

first “virtual band.” The experiment paid<br />

off, to say the least, with Gorillaz<br />

20

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

achieving greater success in both the U.S.<br />

and worldwide than Blur ever reached, and<br />

elevating Albarn to bonafide auteur status.<br />

Albarn has always been a jet setter <strong>—</strong><br />

famously soaking up inspiration from<br />

everywhere he hangs his hat. 2001’s Mali<br />

Music, his collaboration with Afel Bocoum<br />

and Toumani Diabaté & Friends, was born<br />

out of his journeys through Mali, a country<br />

whose music he’s long since championed.<br />

Elsewhere, work on Blur’s comeback<br />

album, 2015’s The Magic Whip, began<br />

during an extended layover in Hong Kong<br />

after a canceled festival appearance in<br />

Japan. In that spirit, Cracker Island is<br />

Albarn’s California album, recorded in LA<br />

and boasting a sunny demeanor and<br />

plenty of Golden State guest stars and<br />

references. The project kicks off with the<br />

Thundercat-featuring title track, with the<br />

bass virtuoso offering his distinctive<br />

plucking and falsetto over a textured<br />

instrumental. While Albarn’s vocal melody<br />

on the verse feels a little rudimentary and<br />

gets a bit redundant, the song’s lyrics<br />

succeed in welcoming us to the album’s<br />

ebullient but sinister setting: “Where the<br />

truth was auto-tuned / And its sadness, I<br />

consumed.” This textural space is<br />

expanded on the following track, “Oil,”<br />

which features the album’s most<br />

surprising guest star, Stevie Nicks. Her<br />

iconic gravely voice enters with a dark<br />

bassline to give the track a gleefully<br />

ominous feel, while her harmonies help to<br />

entrance listeners: “You can't hеlp<br />

yourself anymore and the madness comes<br />

/ You'll be falling into the bass and drum.”<br />

21

“The Tired Influencer” features the album’s<br />

most famous guest star: Siri <strong>—</strong> you know,<br />

the Apple assistant. A song about trying to<br />

keep up with a changing world, you can<br />

almost picture the 54-year-old Albarn<br />

asking Siri how to navigate LA’s labyrinth<br />

of neighborhoods and music trends. A<br />

cultural chameleon, Albarn has always<br />

managed to keep up with the times while<br />

remaining true to himself, and this track<br />

demonstrates that those efforts aren't<br />

always easy. “Silent Running,” one of the<br />

album’s strongest cuts, is a hypnotic<br />

meditation on social media and addiction:<br />

“Machine-assisted, I disappear.” Elsewhere,<br />

“New Gold” is a classic Gorillaz single in its<br />

sound and execution, pairing The<br />

Pharchyde’s Bootie Brown with Tame<br />

Impala’s Kevin Parker. Playing a smaller<br />

vocal role, Albarn shines most in his role of<br />

a curator on this song, craftily blending<br />

the styles of his different collaborators<br />

into something that sounds legitimately<br />

new.<br />

But then there’s “Baby Queen,”<br />

where Cracker Island hits a bit of<br />

a dip. Relying too much on vocal<br />

layering and an over-extended<br />

synth arpeggio to create<br />

atmosphere, the song feels<br />

undercooked in both melody and<br />

structure. “Tarantula” comes off<br />

slightly better, offering a bit more<br />

in the way of groove and style,<br />

aided by Bad Bunny, who delivers<br />

an infectious vocal melody<br />

against the lush reggaeton<br />

production. We then move into the<br />

record’s penultimate track,<br />

“Skinny Ape,” which is another<br />

standout, doing what Gorillaz does<br />

best: taking listeners on a<br />

wild voyage from folksy ballad territory to<br />

a charmingly breezy (almost lazy even)<br />

verse to straight-up synth-pop chaos. It’s<br />

a slow burn with a strange structure, but<br />

one that effectively coheres its disparate<br />

parts. And it has an even stranger<br />

inspiration: apparently born out of an<br />

encounter with an Amazon delivery bot<br />

(classic Albarn fodder). Like a Gorillaz<br />

album, the track is a bit all over the<br />

place, but it’s the kind of oddity that<br />

Albarn so often <strong>—</strong> and indeed here <strong>—</strong><br />

makes work.<br />

While it may not achieve the classic<br />

status of high-point predecessors like<br />

2010’s Plastic Beach <strong>—</strong> Gorillaz’ utterly<br />

fantastic concept album about our<br />

relationship with the environment,<br />

disposability, and authenticity (and one<br />

of the best records of its decade) <strong>—</strong><br />

Cracker Island does feel like something of<br />

a spiritual successor. It’s quintessentially<br />

Albarn in the way it spins anxiety and<br />

isolation into conviviality <strong>—</strong> sailing from<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

one forsaken getaway to another without<br />

forgetting that this is supposed to be a<br />

vacation. Indeed, Albarn’s lonely tourism<br />

may be the defining quality of a Gorillaz<br />

album. Playing genre mixologist, he<br />

curates sounds and collaborators from<br />

unexpected ends of the musical map, and<br />

yet for someone with such a global<br />

network of friends, Albarn always seems<br />

to wind up alone with his thoughts. On<br />

Plastic Beach, the late, great Bobby<br />

Womack sang of the “cloud of unknowing.”<br />

Sometimes peace is best found not<br />

through adventure or achievement, but<br />

by sitting in a space of mystery and<br />

wonder. Cracker Island ends on a similar<br />

notion with the shantying “Possession<br />

Island”: “The time I came to California, I<br />

died / At the hands of the coasting queen /<br />

Where things, they don't exist / And we're<br />

all in this together 'til the end.” <strong>—</strong> NICK<br />

SEIP<br />

LABEL: Parlophone; RELEASE DATE:<br />

February 24<br />