InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 16

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

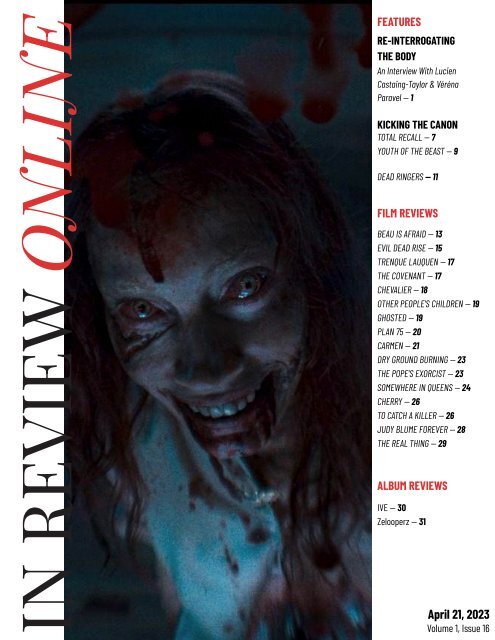

IN REVIEW ONLINE<br />

FEATURES<br />

RE-INTERROGATING<br />

THE BODY<br />

An Interview With Lucien<br />

Castaing-Taylor & Véréna<br />

Paravel <strong>—</strong> 1<br />

KICKING THE CANON<br />

TOTAL RECALL <strong>—</strong> 7<br />

YOUTH OF THE BEAST <strong>—</strong> 9<br />

DEAD RINGERS <strong>—</strong> 11<br />

FILM REVIEWS<br />

BEAU IS AFRAID <strong>—</strong> 13<br />

EVIL DEAD RISE <strong>—</strong> 15<br />

TRENQUE LAUQUEN <strong>—</strong> 17<br />

THE COVENANT <strong>—</strong> 17<br />

CHEVALIER <strong>—</strong> 18<br />

OTHER PEOPLE’S CHILDREN <strong>—</strong> 19<br />

GHOSTED <strong>—</strong> 19<br />

PLAN 75 <strong>—</strong> 20<br />

CARMEN <strong>—</strong> 21<br />

DRY GROUND BURNING <strong>—</strong> 23<br />

THE POPE’S EXORCIST <strong>—</strong> 23<br />

SOMEWHERE IN QUEENS <strong>—</strong> 24<br />

CHERRY <strong>—</strong> 26<br />

TO CATCH A KILLER <strong>—</strong> 26<br />

JUDY BLUME FOREVER <strong>—</strong> 28<br />

THE REAL THING <strong>—</strong> 29<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

IVE <strong>—</strong> 30<br />

Zelooperz <strong>—</strong> 31<br />

April 21, 2023<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1, <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>16</strong>

Re-Interrogating the Body<br />

An Interview With Lucien Castaing-Taylor & Véréna Paravel<br />

Anthropologist-filmmakers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and<br />

Véréna Paravel’s work dissolves the space between their camera and their subject. Previous films<br />

Leviathan and Caniba both treat their respective subjects <strong>—</strong> the marine landscapes of commercial fishing, the domestic world of an<br />

infamous cannibal <strong>—</strong> with startling intimacy, but the proximity of their filmmaking finds new extremes with De Humani Corporis<br />

Fabrica, an observational exploration of eight Parisian hospitals. This new film unfolds across subterranean infirmary tunnels,<br />

operating tables, and inside patients’ bodies; it was assembled over the course of six years, and presents an unflinching document of<br />

state-of-the-art surgical procedures, directing our gaze to otherwise unseeable sights of the human interior.<br />

In the spirit of Stan Brakhage’s monumental autopsy documentation The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes, De Humani probes the<br />

experience of looking at otherwise imperceptible depths of the human body. The film facilitates an encounter between spectators<br />

and the most disavowed corners of their biology. There’s no shortage of haunting corporeal images, visions of the body at its most<br />

frail and vulnerable <strong>—</strong> and yet the film asks us to reckon with what it means to be repelled by the sight of our own biology. At the crux<br />

of De Humani’s ambitious feat (both formally and thematically) is the groundwork for a new relationship with our own bodies, beyond<br />

fear and abjection. I spoke with Castaing-Taylor and Paravel about bodily anxiety and the political imperative of looking at the body in<br />

De Humani; Alice Diop’s reaction to the film; David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future; the work of Walter Benjamin; and plenty more.<br />

As I understand it, the idea for your last movie, Caniba, began with you researching Japanese Pink films and then reorienting<br />

your focus towards Issei Sagawa when you realized he appeared in a Hisayasu Satō film. Did De Humani have a similar<br />

trajectory of shifting focus, or was the central concept solidified from the beginning of your research?<br />

LCT: We read an interview that we apparently gave to a French newspaper called Libération <strong>—</strong> a New York Times-y thing for France <strong>—</strong> I<br />

think in 2011 that said we were already working on this project, which is hard to believe. I think it was just in the idea stage. There<br />

1

were lots of original ideas. One of them was Walter Benjamin’s<br />

concept of the Optical Unconscious, where he basically<br />

compared the way cinema allows us to perceive the world to the<br />

way a surgeon making an incision in the body can perceive the<br />

body. I never really believed in that metaphor, even though it’s<br />

very trendy in critical theory/academic circles. But I wanted to<br />

put it to the test… what would happen if we literalized that<br />

metaphor? What does it mean to study surgery with an empirical<br />

visual proximity and intensity that’s never really been done before?<br />

That was one conceptual start.<br />

We started filming in university-affiliated hospitals in Boston. But<br />

it was impossible to make this film in the US because the<br />

doctors no longer have any rights over the imagery they need to<br />

undertake these surgeries. Though the medical staff was super<br />

open, the hospital administrations were really closed-off. It<br />

would’ve been different if we were coming in from some major<br />

cable network and could’ve given them millions of dollars, but<br />

that wasn’t an option. Then we met François Crémieux, who was<br />

the head of some hospitals in Paris. He does many things. He’s<br />

not really a filmmaker himself, but he did make three films with<br />

Chris Marker: The Balkan Trilogy. He runs a<br />

medical-philosophy-anthropology cinema club in Paris.<br />

[Verena Paravel puffs a vape cloud into the webcam.]<br />

LCT: You just blew smoke in his face.<br />

VP: Sorry.<br />

LCT: Anyway, [Crémieux]’s very interested in bringing<br />

non-medical perspectives. Unlike in the US, he gave us carte<br />

blanche to film anything in the [French] hospitals he was then<br />

director of.<br />

VP: My memory of the project’s genesis is when I was reading<br />

The Boston Globe, which is very strange because I would never<br />

read The Boston Globe. There was a story about how, during<br />

medical training, you’re given a cadaver at the beginning of the<br />

semester. Then, you work on this cadaver during your whole<br />

semester: doing dissection, learning anatomy, learning surgery.<br />

One student was given a cadaver at the beginning of the year<br />

and, when she unveiled the face, it was her aunt. She fainted and<br />

everything. I remember being horrified by the story and, at the<br />

same time, with my weird humor, I found it hilarious. I told<br />

Lucien, “Can you imagine the violence of unveiling and seeing it’s<br />

your family member who’d given their body to science?” We<br />

looked at each other and started to think about what it means to<br />

give your body to science and what’s being done with your body.<br />

Harvard is a place with so many cadavers because of the<br />

prestige. People in this country have the ability to say not only<br />

“I’m going to give my body to science,” but also specify where<br />

you want your body to go. Harvard has a ridiculous amount of<br />

bodies, whereas the rest of medical schools have a serious lack<br />

of bodies to train students. That was the beginning of our<br />

discussion, and we both said at the exact same time: “We should<br />

make a film about that.”<br />

LCT: There’s this expression, “If you can’t get into Harvard when<br />

you’re alive, you can get in when you’re dead.” But you don’t know<br />

that they can also sell your body to other medical schools.<br />

VP: That was the entrance into the hospital world. Then, we soon<br />

realized [filming] in America was too complicated because of<br />

the culture of suing for no reason, for every reason, and every<br />

opportunity. François Crémieux was the key: the miraculous<br />

magic formula to get into the hospital. Once you get in there, it’s<br />

an immense resource of ideas because the hospital itself is a<br />

society in miniature. It’s a microcosm where you feel what’s<br />

going on in society: the violence, the conflicts, religious belief,<br />

social-cultural behavior. Everything is there because the whole<br />

world is coming to the hospital without any filter. Everybody is<br />

there. It’s not that we are equal in front of disease, but we all end<br />

up in hospitals at some point. We all die. We all have a body that<br />

is more or less made of the same organs. That’s an amazing<br />

vantage point.<br />

LCT: Until working in the French public hospitals, the original<br />

conceptual idea we had is indicated by the title. De Humani<br />

Corporis Fabrica, that’s the title of the founding tome of Western<br />

anatomy by a Flemish physician named Andreas Vesalius. There<br />

were seven books in that work. His sense of anatomy was very<br />

revolutionary but it’s now completely outdated. The idea is that<br />

we’d make a film with seven parts, films, or movements. Each<br />

would use a different, contemporary cutting-edge medical<br />

scoping technology that’s come into being the last 10-15 years.<br />

2

Each would be filmed only by that imaging device in seven<br />

different countries. The idea was a much more global approach<br />

to the ways medical imagery allows us to perceive the body in a<br />

way that had never been possible before in history. But also, in<br />

the ways doctors themselves perceive their bodies when they’re<br />

objectifying them, when they’re subjectifiying them, when they’re<br />

mutilating them, when they’re trying to heal them. But it’s a kind<br />

of vision that the rest of the world, aside from these surgeons,<br />

have no access to. The idea was to open up that vision to<br />

humanity at large.<br />

When we got to Paris, we let go of the idea of having seven<br />

different countries, seven different surgical inventions, seven<br />

different scoping technologies because it was absurdly<br />

unprecedented to be afforded carte blanche. To have complete,<br />

unrestricted access was such an opportunity that we didn’t want<br />

to be constrained by the conceptual framework we initially had.<br />

I’m curious about the approach you took to shooting the<br />

surgeries. Did your logistical setup of the camera and its<br />

apparatus vary dramatically from operation-to-operation or<br />

was it consistent throughout?<br />

LCT: The original idea was: we wouldn’t film ourselves. We’d only<br />

record sound and all the imagery in the film would come from<br />

the medical cameras: laparoscopic and celioscopic cameras<br />

that were inside the bodies which the doctors were looking at. So<br />

that footage would be synced up with the sound mostly outside<br />

the body or on the bodies with contact microphones. We’re both<br />

very impetuous and we’re both very ocular centric creatures. So<br />

quite soon, in order to allow ourselves to focus, we also started<br />

filming outside the body. Initially, we used a conventional<br />

camera. But the imagery that gave us wasn’t very exciting and<br />

looked like things we’d seen before. Then we experimented and,<br />

with an amazing engineer in Zurich, fabricated a lipstick camera:<br />

a camera that, as closely as possible, resembles the same optics<br />

and aesthetics as the camera the doctors use. That camera was<br />

breaking down the whole time and we had to find a way to touch<br />

the lens without it burning our hands. But it basically stayed the<br />

same throughout.<br />

Of course, the film is nothing. It’s two hours or something out of<br />

350 hours. Each time we filmed a surgical procedure, and we<br />

filmed hundreds of them, the kind of imagery that the doctors<br />

themselves were using changes according to the operation they<br />

3

were performing, according to the hospital, according to their<br />

resources, etc.<br />

When I saw the movie with an audience last September, I<br />

was struck by very audible exclamations from other people<br />

in the theater. Was that visceral, almost spectacle-like<br />

reception something you anticipated?<br />

VP: We never really have an audience in mind. We were just<br />

worried about being extremely precise. We were expecting the<br />

audience to be maybe a bit touched or overwhelmed at some<br />

points. I think we knew somehow it’s a film that would be lived<br />

and experienced very subjectively. What I’m saying is super<br />

banal because it’s the case for every film. But in this case, it’s a<br />

little different because, as we said earlier, everybody has a body<br />

and everyone has a very particular relationship with their body.<br />

It’s not the same if somebody’s had a prostatectomy. Or if<br />

somebody’s had breast cancer. Or somebody had a parent who<br />

died or who had dementia… They will experience the film<br />

completely differently. We knew this was something we could not<br />

control. When you write a book, you cannot control how the book<br />

is going to be read. This is the case with every film you make.<br />

And this one in particular, we knew that. We did try to be careful<br />

with that because there are many things we didn’t put into the<br />

film because we thought maybe it was just too hard.<br />

LCT: We had to censor ourselves a lot. It doesn’t seem like it<br />

when you see the film because it’s so overwhelming for many<br />

people. But there was so much we took out even though it was<br />

extremely beautiful and incredibly moving or displayed an ethic<br />

of care we thought was really important. It would just be<br />

unwatchable for most viewers. The body is super weird because<br />

it’s the thing we’re closest to in our lives. Your body is the only<br />

thing in the world that you yourself experience from the inside<br />

as well as the outside. It is the most permanent and present<br />

thing in our lives. And yet it is shrouded in taboo, with anxiety<br />

and alienation. Despite its centrality in our lives <strong>—</strong> all we do is<br />

stare at each other’s bodies and inspect our own <strong>—</strong> we have<br />

difficulties transgressing membrane and skin and looking inside<br />

the body.<br />

We weren’t naïve in thinking that wouldn’t generate anxiety, but<br />

we thought it’s important not to turn away our gaze but to<br />

engage with the most important subject in our lives: bodies. We<br />

spend our whole lives pretending we don’t know we’re going to<br />

die. It’s the only thing we know. And we just repress that<br />

knowledge as much as we can. By visualizing the body, we see<br />

our fragility, our resilience. And of course, its fragility is going to<br />

be deeply anxiety-inducing.<br />

VP: Or the contrary. Yesterday, Alice Diop was visiting our class.<br />

She saw the film, and she said she was so scared. We had the<br />

film projected for her, and she was like, “No stay with me! Stay<br />

with me!” At some point I needed to leave, and when I came<br />

back, she was completely transfixed. When the film ended, she<br />

said “I think it healed me.” For her, it was completely therapeutic.<br />

She’s not afraid anymore.<br />

For me, the movie got me to dissect the aversion I felt to<br />

some of the images of the inside of the body and to confront<br />

what it means to look at flesh and feel repulsion to your own<br />

biology. Which was a really unique encounter. I was also<br />

wondering if any of the patients saw the footage of their own<br />

operations?<br />

LCT: Thing is, we filmed hundreds of patients and hundreds of<br />

medical personnel of different stripes. There were all these<br />

screenings in Paris in December and January, like 20 or 30, and<br />

they were invited to many of them. So, we were present for some<br />

of those but not all. The person who had the first operation in the<br />

film <strong>—</strong> the brain surgery for hydrocephalus [treated with] an<br />

endoscopic third ventriculostomy <strong>—</strong> studied his medical<br />

procedure at length in the final cut. That’s also true for some<br />

others. But there’s no way of knowing what percentage of<br />

doctors or patients have seen the film. There were some doctors<br />

and medical staff who came and saw rough cuts towards the<br />

end; we wanted to make sure they found it accurate and not a<br />

misrepresentation. But most people only saw the final film.<br />

What’s the division of labor between the two of you? Are<br />

there specific roles that you individually assume?<br />

LCT: One of us would hold the lipstick camera and the other<br />

would hold the sound. In past films, like Caniba or Leviathan,<br />

there was no division of labor. With Leviathan, the filming<br />

conditions were difficult so one of us would have to hold onto<br />

4

the other to make sure they didn’t fall overboard. But even in that<br />

case, whoever was the least exhausted would hold the camera.<br />

But that also had sound. In this case, we added a microphone to<br />

the camera, so we’d alternate without rhyme or reason. It was<br />

also exhausting; we’d get up and bike to the hospital an<br />

hour/hour-and-a-half every morning at 5 AM. Then we’d get back<br />

at midnight. Whoever was least exhausted would usually hold the<br />

camera and the other one would do the sound.<br />

Do you often find your two approaches and ideas are<br />

simpatico? Or do you find yourselves disagreeing about what<br />

the movie should be?<br />

LCT: There’s almost invariably antipatico. They’re not at all<br />

sympathetic. We fight like cats and dogs.<br />

VP: C'est complètement faux [translation: That’s completely<br />

wrong].<br />

LCT: She’s already disagreeing with me. At the end of a day, one<br />

of us, especially during editing but even during filming, will feel<br />

one way and the other will feel the other. Then, when we meet<br />

again in the editing studio the following morning, I will have<br />

changed position and come to her point of view. And she will<br />

have come to mine. Then we’re like “fuck” because each of us<br />

thinks the opposite. So it’s a constant<strong>—</strong>sorry, it’s a big, stupid<br />

word<strong>—</strong>dialectic going back and forth between the two of us. We<br />

never come to any particular consensus. Every spectator makes<br />

up something different than every other spectator according to<br />

individuality, nationality, gender, race, class position: multiple<br />

different variables that are uncontrollable. Even us, we never<br />

have a singular intellectual perspective; the film still means<br />

different things to us. And what it means to each of us changes<br />

through time. We’re still learning about the film by interacting<br />

with audiences.<br />

VP: I agree… I almost agree, actually. You’re completely right<br />

about the fighting or dialectical process. Can you imagine<br />

agreeing with yourself and being alone? Since we edit<br />

[ourselves], it’s two brains rather than one. It’s like having a<br />

conversation. Somehow, we need the other to trust what we’re<br />

doing. But also, especially when we look at our footage, there is a<br />

common sensibility that is sometimes mind-blowing. Very often<br />

we’re having the same reaction at the same half-second,<br />

5

vibrating in front of the same images. There is a shared<br />

sensibility that is extremely important in our work and<br />

collaboration.<br />

LCT: Even if I don’t vibrate as much as you.<br />

You talked about how Benjamin’s metaphor of the Optical<br />

Unconscious was a starting point, and you talked about how<br />

you’ve never fully bought into it. I’m wondering how the<br />

process of making the movie and thinking back on making it<br />

have changed your understanding of Benjamin’s metaphor?<br />

LCT: It’s complicated… it would take ten pages. Even in ten years<br />

when [the movie] will be in the past, but especially now when it’s<br />

been out for only a couple months in France or almost a year in<br />

festivals. Though we haven’t been to many festivals because it’s<br />

absurd post-COVID in the climate crisis to travel to all these<br />

festivals. But it’s not as if now we’ve reached a certain particular<br />

understanding of either Benjamin or the body. When we started<br />

filming in Paris, not only did the seven-part structure go out the<br />

window but so did the interrogation of that metaphor, partially.<br />

Our understanding of the body and medicine was, and is, in<br />

constant flux.<br />

I still don’t think [Benjamin’s] metaphor holds that much water.<br />

He’s a terribly authoritarian writer who’s completely à la mode in<br />

American universities. To think there’s an optical unconscious<br />

equivalent to the instinctive/psychic unconscious that Freud was<br />

exploring… I don’t think that holds up. He thought painting could<br />

only represent the world from the outside; it was destined or<br />

doomed to have an exterior regard on the world, whereas film<br />

would blow the world asunder in the dynamite of a <strong>16</strong> th of a<br />

second, as he called it. Then, in the detritus of what it captured:<br />

a new vision of the world. It was still very teleological and very<br />

technofilic and romanticized the camera’s vision. The camera’s<br />

vision is as flawed and partial as human vision. In many ways, it’s<br />

not a superhuman vision as Vertov thought; it’s less than human<br />

vision. It’s a constant struggle to work with these audio-visual<br />

technologies, to give us a new perspective on reality and to<br />

perceive the world in ways our own eyes don’t. Or to augment<br />

that apprehension we have of the world. It’s not easy and it’s not<br />

as if there’s one methodology or technology you can pursue that<br />

would allow for that.<br />

VP: Wow…<br />

LCT: We should write on this at some point because, honestly,<br />

it’s a super interesting question.<br />

VP: As I was listening to you, I said, “This is exactly telepathic.<br />

When you were talking I thought, ‘we always refuse to write, but<br />

why?’”<br />

LCT: Because we can’t write. That’s why we use images and<br />

sound… You can write, but I can’t write.<br />

VP: I cannot… you can.<br />

LCT: I also think there’s a political imperative to look at the body,<br />

especially now. With COVID, it’s terrifying how little humanity<br />

seems to have learned from that pandemic. I was really<br />

optimistic during it that there’d be a radically different<br />

relationship to the environment, to the world, to the<br />

extra-human. But I do think we have been fragilized about our<br />

bodies, our mortality. Now is the time to contemplate our<br />

relationship to other species and to the natural world through<br />

the prism of our bodies. The hope is that people like Alice [Diop]<br />

who watch this film, which is very violent in many ways, will<br />

perceive an incredible kind of tenderness. Paradoxically,<br />

perhaps, they’re able to reconcile <strong>—</strong> as you were <strong>—</strong> with their<br />

bodies.<br />

It’s not disgusting, it’s not gory. People often compare it with<br />

Cronenberg’s film [Crimes of the Future]. It’s the opposite of<br />

Cronenberg’s film. But I still think there’s this prohibition about<br />

looking at one’s body that has to be interrogated. And if we’re<br />

going to have a healthy relationship to the rest of the world,<br />

other species (animal, plant, and mineral), that has to start<br />

with a capacity for reinterrogating our own relationship to our<br />

bodies.<br />

VP: I was talking about the hospital as a microcosm of society,<br />

but the body itself is. It’s a place of multiple cohabitation<br />

between viruses and bacteria. It’s also a place that cannot be<br />

sustainable if you want to push the metaphor of being alive.<br />

There’s no body that can survive without the care of other<br />

bodies. <strong>—</strong> INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY RYAN AKLER-BISHOP<br />

6

KICKING THE CANON<br />

TOTAL RECALL<br />

Paul Verhoeven<br />

"Reality is that which, when you<br />

stop believing in it, doesn't go away."<br />

- Philip K. Dick<br />

With his bionic biceps threatening to split his skin wide open in a<br />

fashion not dissimilar to the Hulk with his shirts and that endearing<br />

accent, sort of Russian but not quite, that he never shook, Arnold<br />

Schwarzenegger, an immigrant, was the paradigm of big dumb '80s<br />

American action movies, a hulky hero who could mow down droves of<br />

nondescript bad guys with a machine gun so big it's comical while<br />

tossing out lovably lame one-liners with a wry smile that lets you know<br />

he loves this. And the joy, the unfettered joy with which he<br />

serves those quips, often bad puns that don't sound so<br />

different from a Dad Joke, is the kind of acting<br />

you don't learn from the Actors Studio.<br />

7

KICKING THE CANON<br />

In the '80s, after Sylvester Stallone <strong>—</strong> who, remember, got<br />

famous with an intimate, modest film playing a bum who refuses<br />

to give up on his dreams with aching vulnerability <strong>—</strong> made the<br />

move to machismo and bombast, moviegoers were given a<br />

choice: Team Arnold or Team Sly. It's not really a fair comparison,<br />

as Stallone is also a writer and director (and a good one, too,<br />

adroit at montage in ways that hark back to the great Russian<br />

filmmakers of the silent era) and was a respected actor before<br />

he transmogrified into the corporeal personification of<br />

testosterone; Arnold was a bodybuilder, the best ever, who<br />

became an actor to further engorge his ego (watch Pumping Iron<br />

and witness his narcissism and bloated sense of<br />

self-importance) and who found early success in the movies<br />

playing big meaty men. He soon developed an inimitable charm<br />

that made him one of American cinema's most enthralling<br />

presences, a Reagan-era John Wayne, but he was never<br />

considered a good actor.<br />

Well, Arnold's pretty good in Paul Verhoeven's Total Recall, a loose<br />

adaptation of a story by perpetually poor pill-popper Philip K.<br />

Dick. As Doug Quaid, a hulky nobody who becomes an<br />

interplanetary hero, or maybe has a schizoid embolism after a<br />

memory implantation operation gone awry, Arnold exudes that<br />

inimitable charm that made him a megastar. But it's here<br />

tinctured with a self-awareness (the embryonic stage of the kind<br />

of honest self-exploration that imbues his performance in the<br />

great Last Action Hero, still his best role) that, if you interpret the<br />

film <strong>—</strong> as Verhoeven does <strong>—</strong> as the fantasy of a Joe Schmo who<br />

dreams of being somebody important, is actually pretty sad. Go<br />

back to Pumping Iron <strong>—</strong> the seminal documentary purveying the<br />

world of bodybuilding <strong>—</strong> when Arnold, then 27 years old and<br />

already a legend and almost heavenly idol to his acolytes (see:<br />

the scene at the prison), openly indulged his egotism, literally<br />

saying he admires "powerful men," like dictators, and aspires for<br />

greatness <strong>—</strong> and not just greatness, but being the best at<br />

everything he does. In Total Recall, he plays an unexceptional guy<br />

who wants to be great, who finds his dreams literally in his<br />

dreams while he sits still, comatose, forever in his own mind. And<br />

the face he makes when he is hit in the balls <strong>—</strong> more than once!<br />

<strong>—</strong> is unmatched, all his facial muscles clenching like digits in a<br />

fist.<br />

Verhoeven is a consummate craftsman whose films couldn't<br />

have been made by anyone else, but he doesn't really have a<br />

distinct visual style, at least regarding compositions and<br />

movement and so on. His approach isn't showy, but the images<br />

are always coherent, as is the action, even when<br />

things get surreal or grotesque; the loving detail of<br />

the mutants evinces a bold humanism you don't find<br />

in many $100 million blockbusters. And, of course,<br />

Paul was the satirist par excellence of '90s<br />

Hollywood. Here, he eviscerates, with brutal care,<br />

capitalism (the craven villain, played slimily by Ronny<br />

Cox, who was similarly slimy in Robocop, charges<br />

exorbitant prices for air on Mars, the way America<br />

charges disturbingly high fees for basic necessities),<br />

imperialism, the police force, etc. He also butchers<br />

bodies. The somatic savagery <strong>—</strong> Arnold uses a man<br />

as a meat shield, as bullets batter the body and<br />

blood sprays from holes spurting all over his torso,<br />

for instance <strong>—</strong> is excellently excessive; it's<br />

Verhoeven's willingness to be so mean, his<br />

conviction obvious each time a bullet collides with<br />

flesh, that makes the whole thing so fun. He takes<br />

glee in it, thus, so do we. <strong>—</strong> GREG CWIK<br />

8

KICKING THE CANON<br />

YOUTH OF THE BEAST<br />

Seun Suzuki<br />

Seijun Suzuki made his name with a string of Nikkatsu-produced genre flicks <strong>—</strong> The Naked Woman and the Gun (1957), Voice Without a<br />

Shadow (1958), Man With a Shotgun (1961) <strong>—</strong> but is probably best known to contemporary audiences for his yakuza films. A relatively<br />

inhibited take on American gangster noirs quickly evolved into a kaleidoscopic assault on the form that made him both beloved and<br />

infamous, with what’s now his most acclaimed work <strong>—</strong> 1967's eclectic, satirical yakuza classic Branded to Kill <strong>—</strong> initially landing as a<br />

critical and commercial failure, and leading to Suzuki's dismissal by Nikkatsu, for making "movies that make no sense and no money,"<br />

according to the filmmaker. This then led Suzuki to successfully sue the production company, but the ordeal cost him a decade-long<br />

blacklisting.<br />

Though Suzuki’s freewheeling cinematic sensibilities can actually be traced all the way back to his debut film, 1956's Victory is Ours,<br />

the first genuine flashes of his trademark style appeared in the 1958 crime film Underworld Beauty. Not only was this the first of his<br />

films credited to Seijun Suzuki (as opposed to Seitaro Suzuki, his birth name), but it also featured an unorthodox visual creativity <strong>—</strong><br />

cleverly obscured nudity; deep, mysterious shadows; creepy mannequin set design <strong>—</strong> which was nevertheless noticeably restrained<br />

by Nikkatsu's expectations of commercial viability. Take Aim at the Police Van (1960) and Detective Bureau 23: Go to Hell, Bastards!<br />

(1963) can be similarly described. But then came Youth of the Beast, which marked a true turning point for the filmmaker.<br />

One of four Suzuki films released in 1963, Youth of the Beast saw the auteur truly embrace his playful pop artistry for the<br />

first time <strong>—</strong> even Suzuki himself called it his "first truly original film." The plot is essentially a spin on Kurosawa's<br />

1961 samurai film Yojimbo, wherein a wandering ronin, Kuwabatake Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune), infiltrates the<br />

organizations of two opposing crime bosses struggling for supremacy<br />

to bring peace to a small village. But unlike<br />

9

KICKING THE CANON<br />

Kurosawa's classic, Suzuki's crime tale has no place for such<br />

noble aims. Joji "Jo" Mizuno (the famously chipmunk-cheeked Joe<br />

Shishido) is an ex-cop driven solely by revenge. Having been<br />

wrongfully convicted of embezzlement, the newly released Jo<br />

becomes singularly focused on avenging the murder of his loyal<br />

former partner, whose death was staged to look like a lover's<br />

suicide.<br />

Jo's pursuit of "justice" becomes a relentless, violent, and slyly<br />

comical odyssey through Kobe's criminal underworld. Although<br />

1966's Tokyo Drifter would mark Suzuki's first identifiably<br />

deconstructionist take on the genre, Youth of the Beast scans as<br />

similarly satirical. The film occupies a space between<br />

straightforward gangster film homage and Godardian<br />

pranksterism, amplifying genre tropes to near-absurd levels with<br />

increasingly<br />

convoluted<br />

violence, plot<br />

machinations,<br />

and set<br />

pieces <strong>—</strong> at one<br />

point, Jo disposes<br />

of his adversaries<br />

while hanging<br />

upside down from a chandelier <strong>—</strong> while occasionally pushing<br />

things into the realm of the avant-garde. For every blade<br />

violently shoved under a fingernail, there is a shot of radiant red<br />

flowers illuminating the otherwise black-and-white frames of the<br />

film's intro. And Suzuki's farcical tough-guy introduction for Jo <strong>—</strong><br />

he beats up young delinquents before heading to a club to drink<br />

and beat up some more people <strong>—</strong> feels like a purposeful<br />

escalation of Breathless' Bogart-obsessed main character, Michel<br />

(Jean-Paul Belmondo).<br />

Youth of the Beast’s gritty textures don't rival Tokyo Drifter's<br />

arresting production design. But Suzuki still provides his share of<br />

striking images, such as when Jo invades the office of crime<br />

boss Shinzuke Onodera (Kinzo Shin). The head honcho's office<br />

walls are illuminated by images of American and Japanese<br />

B-movie gangster melodramas <strong>—</strong> the kind of films that Suzuki<br />

was slowly but surely leaving behind. (Incidentally, Onodera, as<br />

well as his rival Tetsuo Nomoto (Akiji Kobayashi), are depicted as<br />

weaselly, bottom-line-obsessed businessmen, far removed from<br />

the honor codes often employed to romanticize Japanese<br />

organized crime.) This juxtaposition ultimately acknowledges the<br />

framework that the film <strong>—</strong> for all its clever subversions <strong>—</strong><br />

operates within, obscuring the visceral violence that ensues by<br />

calling attention to its artificiality.<br />

This unsentimental, stylized approach would prove influential on<br />

filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Park Chan-wook, John Woo,<br />

and Takashi Miike,<br />

whose genre efforts<br />

often echo Beast's<br />

elaborate brutality.<br />

Even Scorsese might<br />

have looked to<br />

Keiko's (Naomi<br />

Hoshi) agonizing<br />

junkie floor crawl for<br />

The Wolf of Wall<br />

Street's infamous<br />

Quaaludes scene.<br />

Suzuki's later, more<br />

surreal efforts<br />

overshadow the<br />

legacy of the first<br />

true Suzuki original,<br />

somewhat, and he<br />

remains tragically<br />

under-discussed as<br />

a talented dramatic<br />

filmmaker (1964's<br />

Gate of Flesh and<br />

1965's Story of a<br />

Prostitute rank<br />

amongst his best<br />

work). But it’s with<br />

Youth of the Beast<br />

that his anarchic<br />

vision truly snapped into focus, and at last converged with a<br />

searing poignancy, felt in its ending: after the antagonist finally<br />

dies a horrible, razor blade-related death, Jo succumbs to<br />

despair and has a vision of a grayscale graveyard, where<br />

flowers once again gleam with red-hot menace. <strong>—</strong> FRED<br />

BARRETT<br />

10

DEAD RINGERS<br />

It’s hard not to see the Dead Ringers miniseries as yet<br />

another domino tumbling on the remake assembly line<br />

that turns everything from The Parallax View to Fatal<br />

Attraction into half-hearted content, primed for<br />

couch-locked consumption. Credit where it's due,<br />

Cronenberg’s underrated 1988 thriller at least makes<br />

for an intriguing selection, given its restrained<br />

manner, disturbing gynecological sojourns, and the<br />

demanding dual performance of its lead-playing twin<br />

doctors stuck in a codependent spiral. Anyone<br />

looking to play it safe (though what Cronenberg<br />

remake really is?) could have chosen to adapt<br />

eXistenZ, whose twisty, mind-bending plot and<br />

science fiction trappings seem at least better suited for<br />

serialization than this icy, melodramatic chamber piece.<br />

That said, the assembled team here is pretty strong:<br />

there’s dual-lead Rachel Weisz, blending the composed<br />

vulnerability of Disobedience with the ravenous bite of The<br />

Favourite; the likes of Sean Durkin (Martha Marcy May Marlene) and<br />

Karyn Kusama (The Invitation) directing; and it’s all run by<br />

playwright/screenwriter Alice Birch, who penned the phenomenal<br />

Florence Pugh breakout, Lady Macbeth, and whose impressive<br />

television credits include Normal People and Succession. It’s all this<br />

squandered potential that makes the predictably tepid end result <strong>—</strong> a<br />

parade of extraneous themes, characters, and plot lines, scattered across six<br />

disjointed episodes <strong>—</strong> such a letdown.<br />

This fumbling effort highlights the unavoidable catch-22 of the<br />

movie-to-miniseries pipeline: a straightforward remake would be considered<br />

a futile exercise in imitation, but the full-scale remodel (as embarked on<br />

by Birch) remains awkwardly chained to its source material, leaving its<br />

myriad ambitions out of arm's reach. The original narrative of<br />

Beverly and Elliot Mantle's co-dependent self-destruction still<br />

grounds the project, but there are now hours of filler to dilute<br />

Cronenberg’s concentrated dose. Long sequences with the<br />

twins' parents, their sociopathic angel investors,<br />

their artist-in-residence housekeeper, the<br />

11

magazine writer working on an expose <strong>—</strong> it’s a cascade of false<br />

starts and half-thoughts trailing off before they ever get<br />

anywhere interesting. This undercooked quality is most<br />

pronounced with the reorientated focus on the politics of<br />

reproductive health. This shift, defined by the Mantle twins’<br />

gender swap, might promise to be the series' greatest strength, a<br />

timely and clever inversion of some of the prickly, misogynistic<br />

undertones in the original brothers' psychology. But just like in<br />

the aforementioned threads, this too is presented in<br />

Twitter-bent one-liners and scattershot fragments that never<br />

have space to breathe.<br />

Accompanying the overstuffed scope of ideas is a similarly<br />

overstuffed stylization, presented in anamorphic widescreen to<br />

give ample room for the twins to share the frame. Where<br />

Cronenberg’s version avoided stressing its central gimmick, the<br />

miniseries embraces it with relish and abandon, collecting both<br />

Weiszs together in a shot as much as possible. Similarly absent<br />

is the restraint of the original’s visuals. Peter Suschitzky’s muted<br />

palette resembled a soap opera, lulling the viewer into an uneasy<br />

calm, only to blossom in spectacular moments like a bondage<br />

scene featuring rubber tubing and medical clamps shot in woozy<br />

blues, or the gloom of the operating theater pierced with the<br />

smoldering crimson of the Mantles’ surgical garb. Birch’s version<br />

nods at some of these ideas, but strikes a frustrating<br />

middle-ground of colorful, nicely framed banality that plays like<br />

microwaved leftovers. All this is goaded on by a snappy musical<br />

score and punctuated by an endless parade of tacky needle<br />

drops. If Cronenberg bemoaned the cost of featuring a single<br />

song in his film (“In The Still of the Night'' by The Five Satins), it’s<br />

tough to imagine what his reaction would be to this soundtrack,<br />

so stuffed with overused hits <strong>—</strong> “Sweet Dreams,” “Tainted Love,”<br />

and so forth <strong>—</strong> that it chugs along almost like a jukebox musical.<br />

There are some bright spots here and there. Weisz’s take on the<br />

twins may lack nuance <strong>—</strong> Jeremy Irons’ performance remains<br />

untouched <strong>—</strong> but it makes up for it in campy exuberance, which,<br />

accompanied by some devilishly funny writing and a strong<br />

supporting cast, helps keep things gliding along. Particular<br />

standouts include Jennifer Ehle’s razor-witted Rebecca Parker,<br />

the caustic investor the Mantles have to beg for funding for their<br />

birthing centers, and Ntare Guma Mbhaho Mwine as a writer<br />

digging into the Mantles, stealing every single scene he’s in with<br />

relaxed poise and finely tuned, simmering charm. Where the<br />

show really stumbles, however, is in building its emotional<br />

backbone. Weisz has no chemistry with Britne Oldford, who plays<br />

Beverly’s lover, an issue compounded by the fact that Beverely’s<br />

character has been restructured in such a way as to become an<br />

idealistic husk of what he once was. In the original, Beverly was<br />

the more empathetic of the two, but far less predictable,<br />

susceptible to addiction and psychological breakdown. Elliot was<br />

colder, crueler, and more playful, but defined by a calm<br />

demeanor and a rigid sense of control. Instead, Birch’s version<br />

sanctifies Beverly and transfers all flaws over to Elliot. Out of<br />

everything that frustrates in this Dead Ringers, its oversimplified,<br />

good twin/bad twin dichotomy is most destructive to the heart<br />

of the source material.<br />

By the time you’ve made it to the sixth and final episode, the<br />

incongruities in theme and tone and the sheer number of<br />

abandoned plot threads start to seem like insurmountable<br />

failings. The show races toward its ending with the sweaty<br />

energy of a series canceled halfway through, one desperately<br />

trying to cobble together a satisfying conclusion amidst its final<br />

throes. Following the trend set by every poorly thought-through<br />

deviation from the source material leading up to it thus far, Birch<br />

declines the original’s beautifully cutting closer in favor of a<br />

broader, tackier, and more predictable finale. The muddled<br />

nature of this desperate final bow stands in stark contrast to the<br />

quiet dignity of Cronenberg’s operatic ending, a move that seems<br />

to be at total odds with the warmer, more empathetic approach<br />

toward the Mantles that the series until this point exhibits. Maybe<br />

the most charitable reading here would be that the disjointed<br />

flow from one episode to the next suggests that each should be<br />

seen as improvisations on a theme <strong>—</strong> siblings, parents, class,<br />

motherhood <strong>—</strong> and yet, as poorly as these work as a whole, they<br />

seem even more wanting in isolation. The ultimate takeaway<br />

here is that, tempting as it may be, trying to xerox the dark<br />

alchemy of Cronenbergian narrative is certainly<br />

a fool’s errand. Cronenberg’s discordant themes, at once<br />

excessive and elegant, aren’t threaded together but instead<br />

violently fused; the final, imitative product that is this Dead<br />

Ringers mini-series is a fender-bender enervated by caution,<br />

whereas the real deal was an expressway collision, its potency<br />

crawling up your spine <strong>—</strong> glass, metal, and protruding flesh. <strong>—</strong><br />

IGOR FISHMAN<br />

12

FILM REVIEWS<br />

BEAU IS AFRAID<br />

Ari Aster<br />

Joaquin Phoenix’s first scene in Beau Is Afraid takes place in his<br />

therapist’s office, setting the story in motion while also<br />

presenting a roadmap of sorts for everything that follows.<br />

Phoenix plays the titular Beau, a forty-something-year-old virgin<br />

with truly unfortunate levels of male pattern baldness and a<br />

prominent spare tire (the weight swing between this and his<br />

performance in Joker, only a few years ago, has to be 75 lbs, at<br />

minimum). In the aforementioned scene, Beau and his doctor are<br />

grappling with the prospect of traveling out of town to visit his<br />

domineering mother; posing questions that only agitate Beau<br />

further (“do you ever wish that she was dead?”) from behind a<br />

Cheshire Cat grin, the doctor (Stephen McKinley Henderson)<br />

sends Beau off with a prescription for a new anxiety medication,<br />

replete with terrifyingly commonplace side effects (“If you start<br />

to feel warm or have an elevated heart rate, that’s bad”). Given<br />

this framing, one could view everything that happens in this film<br />

thereafter as the result of an adverse reaction to Beau’s new pills,<br />

but that would be far too prosaic a read on director Ari Aster’s<br />

bugfuck odyssey. Instead, Beau Is Afraid aspires to do no<br />

less than dramatize an American Psychiatric Association<br />

textbook’s worth of phobias and stressors <strong>—</strong> large, small, and<br />

yet-to-be-classified. The film is something like the Terminator,<br />

only it’s in relentless pursuit of that elusive trigger that will send<br />

the viewer into a full-on panic attack.<br />

Living in an under-furnished, third-story apartment in the sort of<br />

urban hellscape only found in Fox News fever dreams, Beau steps<br />

over dead bodies lying in the road, outruns mentally ill vagrants,<br />

and absent-mindedly wanders past floor-to-ceiling vulgar graffiti<br />

and warnings about brown recluses in the building. And this is all<br />

to get back to an abode that looks like the kind of space single,<br />

middle-aged men rent out shortly before hanging themselves. It’s<br />

the type of place where residents are menaced by a nude serial<br />

killer (a news report helpfully clarifies that the suspect is<br />

circumcised), and the local citizenry proceed to congregate in<br />

zombie-like hordes in the middle of the street. And this is Beau’s<br />

safe space: the place he’s being guilted into leaving for a<br />

weekend visit with his emotional-terrorist, titan-of-industry<br />

mother, Mona (played by Patti Lupone in present-day scenes, and<br />

Zoe Lister-Jones in flashback).<br />

13

FILM REVIEWS<br />

For much of the film’s masterful first hour, we watch Beau<br />

attempting to navigate cascading inconveniences that conspire<br />

to derail his trip. The water in his apartment has been shut off;<br />

an irate neighbor keeps sliding passive-aggressive notes under<br />

his door in the middle of the night, asking Beau to turn down the<br />

music when no music is even being played; a slept-through alarm<br />

clock makes Beau late for the airport. Then someone steals<br />

Beau’s house keys right out of the lock <strong>—</strong> after he scampered<br />

back inside for only a few seconds to grab his dental floss, a<br />

fitting character note <strong>—</strong> leaving even the man’s inner sanctum<br />

vulnerable. It seems reasonable, then, that Mona will be forgiving<br />

of him delaying his trip by a few hours so that he can call a<br />

locksmith. She is not. The film continues on like this, building<br />

indignity on top of indignity, reaching a crescendo when Beau<br />

receives horrifying news from home, in the least comforting way<br />

imaginable, shortly before being run into by an RV while running<br />

naked through the streets (his distended and severely swollen<br />

testicals occasionally jostling into the frame). And that’s when, as<br />

the expression goes, things start to get weird.<br />

Beau Is Afraid is the eagerly anticipated follow-up from Ari Aster<br />

(Hereditary, Midsommar), who, after only three feature films, has<br />

emerged as the most breathlessly hyped name in A24’s stable of<br />

in-house directors. Up until now, a genre filmmaker specializing<br />

in tightly-controlled, large-canvas squirm-fests, Aster abandons<br />

overt horror here (although there’s no shortage of shocking<br />

violence and unsettling moments) and doubles down on his pet<br />

theme of the lasting harm parents inflict upon their children.<br />

There’s something upsetting for Beau to fret about even in the<br />

most innocuous of places <strong>—</strong> for example, the cozy suburban<br />

home he’s taken to convalesce at by a way-too-chipper Nathan<br />

Lane and Amy Ryan. But, invariably, the film works its way back<br />

to the codependency and sexual dysfunction instilled in him by<br />

his mother at a young age. Aster’s previous films were legitimate<br />

hits, and Beau Is Afraid carries itself with the swagger of an artist<br />

comfortable burning through whatever capital they’ve amassed<br />

in service of chasing an undiluted vision. That extends to the<br />

film’s elephantine runtime (just a hair under 180 minutes) and<br />

comparatively large budget, but also to its disquieting framing of<br />

motherhood, sexuality, the human body, and the music of Mariah<br />

Carey. It’s an expansive, occasionally turgid film that seems<br />

designed to test an audience’s patience, particularly during a<br />

longish digression where Phoenix, on the run, stumbles upon a<br />

roving theater troupe that’s set up camp in the woods. It’s a<br />

confounding detour smack dab in the middle of the film, blurring<br />

the line between performer and audience, reality and metaphor,<br />

live-action and animation. To what end it serves remains unclear<br />

other than that it’s of a piece with the film’s Kaufman-esque pop<br />

surrealism and the director’s “who are you to say no to me?”<br />

mandate.<br />

Maddeningly inscrutable by design, Beau Is Afraid <strong>—</strong> with its<br />

nightmarish Freudian imagery, “better living through<br />

pharmaceuticals” thematizing, and nods to both Judaism and<br />

Kafka <strong>—</strong> is all but begging to be solved (Internet explainers and<br />

crowd-sourced Reddit threads are due any minute now).<br />

Interpreting what it all means may not actually be worth the<br />

squeeze, but that’s almost incidental when put up against the<br />

film’s surface-level pleasures. There’s the precision of the<br />

filmmaking, with its emphasis on vertical compositions <strong>—</strong> the<br />

film is playing on IMAX screens in select markets for good reason<br />

<strong>—</strong> and building risible gags entirely through production design,<br />

set dressing, and throwaway props (e.g., an early scene finds<br />

Beau microwaving a TV dinner that boasts a flavor profile<br />

combination of Irish and Hawaiian cuisine). For the sort of<br />

person who can roll with it, there's a queasy yet intoxicating<br />

discomfort to the way the film takes pliers and a blowtorch to the<br />

viewers’ last nerve, eliciting waves of shame and purposeful<br />

befuddlement from every new scenario Beau stumbles into. And<br />

then there are the heavily-stylized, outsized performances. On<br />

one end of the spectrum, you have Phoenix, his Beau so<br />

paralyzed by fear, humiliation, and conflicting instruction that he<br />

all but slides into catatonia. On the other end, there’s Lupone’s<br />

character: a sucking wound of self-justification, pettiness, and<br />

the desire to manipulate an adult son she still treats like a child,<br />

earning the actress honorary status in the Jewish Mothers Hall of<br />

Fame. The film’s ambitions and demonstrable craft aren’t<br />

14

FILM REVIEWS<br />

redeeming in and of themselves, and certainly don’t absolve the<br />

film of its lumpiness, its narcissism, or some of its more juvenile<br />

tendencies, but the more off-putting qualities aren’t inherently<br />

disqualifying either. And there’s a bit of a perverse thrill in<br />

something this unaccommodating being unleashed on audiences<br />

probably expecting the latest iteration of “elevated horror.” In the<br />

end, Beau Is Afraid is something like a long therapy session: it’s<br />

expensive, self-indulgent, and should have probably remained<br />

private. But there’s also a morbid fascination in observing it, and,<br />

ultimately, the mother’s probably to blame. <strong>—</strong> ANDREW DIGNAN<br />

DIRECTOR: Ari Aster; CAST: Joaquin Phoenix, Nathan Lane, Amy<br />

Ryan, Parker Posey; DISTRIBUTOR: A24; IN THEATERS: April 21;<br />

RUNTIME: 2 hr. 59 min.<br />

EVIL DEAD RISE<br />

Lee Cronin<br />

The latest installment of the Evil Dead franchise, Evil Dead Rise,<br />

opens with a sequence that will be instantly recognizable to<br />

longtime fans of the series. Under the opening credits, an unseen<br />

force propels itself, at breakneck speed, through a foggy forest,<br />

across clearings and creeks, hurtling itself toward an<br />

unsuspecting victim. It’s really a bit of cheeky misdirection: the<br />

ominous, quickly moving presence is a small drone being piloted<br />

by an obnoxious frat boy type, tormenting a young woman who’s<br />

just trying to read by the lake. This smartly undercuts the tension<br />

before things start to get grizzly, about five minutes hence, while<br />

at the same time putting its own spin on one of the more familiar<br />

visual tropes of these films. It’s also just a little bit clever <strong>—</strong> a<br />

quality that’s otherwise in short supply in a film that, while<br />

suitably gory and proficiently made, lacks any real sense of<br />

invention or personality.<br />

That woods-set prologue notwithstanding <strong>—</strong> the film eventually<br />

circles back to how we even ended up there and who these<br />

anonymous victims are, and in a decidedly perfunctory manner <strong>—</strong><br />

Evil Dead Rise differentiates itself from its predecessors by<br />

setting its deadite mayhem not in a cabin in the woods but rather<br />

in a dilapidated apartment complex in Los Angeles. It’s not quite<br />

putting Jason Voorhees in outer space, but for a franchise that<br />

leans so heavily on the isolation and vastness of the wilderness,<br />

moving the action to an urban center rife with<br />

modern amenities is an admirable upending of the formula. We’re<br />

introduced to touring guitar tech and absentee cool aunt, Beth<br />

(Lily Sullivan), who pops in to visit her older sister, tattoo artist<br />

Ellie (Alyssa Sutherland), and her three children on a dark and<br />

stormy evening. Beth has only just learned she’s pregnant, and,<br />

whether she’s willing to admit it or not, she’s looking to Ellie to tell<br />

her everything’s going to be okay. However, she finds in Ellie a<br />

woman at her wits’ end; she’s been abandoned by her husband<br />

and the father of her kids while frantically trying to find a new<br />

place for everyone to live as the building, which is falling down<br />

around them, has been scheduled for demolition in a few weeks.<br />

With Beth never being around to offer emotional support to Ellie,<br />

cracks have emerged in their relationship, which lends the visit a<br />

bit of an edge (Ellie even has the cruel habit of dismissing her<br />

little sister’s career by calling her a groupie).<br />

Speaking of cracks, a literal one opens up in the basement,<br />

triggered by an earthquake (it is Los Angeles, after all).<br />

Undaunted by the shaky foundation or the notion that venturing<br />

into unlit, subterranean chambers is how one-third of all horror<br />

films begin, Ellie’s eldest child and amateur DJ, Danny (Morgan<br />

Davies), climbs down into an abandoned bank vault where he<br />

finds a spooky yet familiar book (bound in human skin, penned in<br />

blood, featuring incantations and horrifying illustrations… you<br />

know the drill) and, even more germane to his interests, some old<br />

records. Against the wishes of younger sisters Bridget (Gabrielle<br />

Echols) and Kassie (Nell Fisher), Danny brings the book and the<br />

vinyl upstairs and plays the record on his turntable. Hoping he’s<br />

found an obscure beat he can sample, Danny instead is greeted<br />

by a hundred-year-old recording of a priest translating the “Book<br />

of the Dead,” and in the process unleashes an ancient, evil spirit<br />

into the apartment building, setting the stage for a long night of<br />

demonic possession and ultraviolence.<br />

Directed by Irish filmmaker Lee Cronin (The Hole in the Ground),<br />

Evil Dead Rise doesn’t so much resemble Sam Raimi’s seminal<br />

1981 film The Evil Dead or either of its two sequels as it does the<br />

dozens of disposable horror films produced under Raimi’s<br />

production shingle, Ghost House Pictures (which mostly churns<br />

out films in the 30 Days of Night, The Boogeyman, and The Grudge<br />

franchises). Gone is any sort of hand-tooled ingenuity or reckless<br />

disregard for the safety of the actors <strong>—</strong> the Raimi films, with<br />

their Three Stooges-inspired violence and a tendency to put star<br />

15

FILM REVIEWS<br />

Bruce Campbell through the wringer without the benefit of a<br />

stuntman, often had more in common with the Jackass movies<br />

than your typical horror film <strong>—</strong> replaced with photo-realistic<br />

gore, CGI effects, and a cobalt and gunmetal gray color palette. In<br />

other words, the film is slick-looking and hits its marks, and<br />

when a possessed character begins masticating a wine glass,<br />

shards of glass poking through their esophagus as they swallow,<br />

it’s genuinely disgusting. As it is when another character has a<br />

cheese grater raked across their calf, and yet again when<br />

someone has one of their eyeballs sucked out of their skull. Is it<br />

scary, though? Viewers' mileage will vary, but the more important<br />

question is whether any of this is especially fun. The answer,<br />

regrettably, is no.<br />

Evil Dead Rise is under no obligation to match the punch-drunk<br />

energy of the Raimi films <strong>—</strong> honestly, good luck even trying <strong>—</strong> but<br />

its absence does underscore just how generic and kind of joyless<br />

this all is. It’s yet another well-lit tour of an abattoir. The sisterly<br />

angst and anxiety over Beth becoming a mother are only<br />

introduced to give assorted possessed characters something to<br />

taunt the living over <strong>—</strong> although the latter does allow the film to<br />

replicate the Ripley and Newt dynamic with Beth and Kassie,<br />

complete with lifting chunks of James Horner’s iconic Aliens<br />

score for its action finale. Nor is there much inspiration in the<br />

high-rise setting: the earthquake knocks out the power and cell<br />

reception, and takes out the elevator and stairs so that the<br />

characters might as well be stranded in the middle of the woods<br />

for all that the change of venue matters (you’d think some of the<br />

tenants on the lower floors might try and investigate all the<br />

shotgun blasts). Instead, Evil Dead Rise mostly gets its kicks by<br />

sneaking Easter Eggs into the film, some of which are more<br />

thoughtful (a gardener’s truck in the parking garage is attributed<br />

to Dr. Fonda’s Tree Surgeon, a simultaneous nod to the<br />

prominence of chainsaws in the franchise, malicious trees, and<br />

even the actress Bridget Fonda who cameos in 1993’s Army of<br />

Darkness) than others (Sullivan randomly repeating one of<br />

Campbell’s catchphrases by telling a deadite “come get some”<br />

before blasting it with a shotgun).<br />

If there’s a saving grace to the film, it’s Sutherland’s performance.<br />

An Australian performer, like nearly everyone else in the cast<br />

(watching all the actors fighting a losing battle with their<br />

American accents is often more diverting than the story), the<br />

actress best known for TV’s Vikings does some of the best<br />

physical acting in recent memory. A tall, spindly beauty in a red<br />

Farrah Fawcett blowout, the actress <strong>—</strong> who’s the first to be taken<br />

by the evil spirit and is ostensibly the primary antagonist <strong>—</strong><br />

spends the film alternating between ramrod rigidity and<br />

contorting her body in inhuman angles, at all times wearing a<br />

deranged perma-rictus (the actress spends much of the film<br />

staring into a peephole lens, the fisheye effect only further<br />

distorting her face). In a film where everyone and everything is<br />

so dreadfully grim, Sutherland, finding a middle ground between<br />

Mommie Dearest and Joker, comes the closest to capturing the<br />

anarchic spirit of the films in whose footsteps it follows. Why so<br />

serious, indeed? <strong>—</strong> ANDREW DIGNAN<br />

DIRECTOR: Lee Cronin; CAST: Lily Sullivan, Alyssa Sutherland,<br />

Morgan Davies; DISTRIBUTOR: Warner Bros. Pictures; IN<br />

THEATERS: April 21; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 37 min.<br />

<strong>16</strong>

FILM REVIEWS<br />

TRENQUE LAUQUEN<br />

Laura Citarella<br />

“Trenque Lauquen, Argentinean director Laura Citarella’s third<br />

feature, shares with that film not just its production outfit El<br />

Pampero Cine, but also two of the film’s leads, Laura Paredes<br />

and Elisa Carricajo. (Llinás also has a producer credit.) Granted,<br />

four hours is a ways off from fourteen, and instead of Llinás’<br />

intentionally incomplete stories, Trenque Lauquen comprises<br />

elliptical fragments which do, finally, offer some semblance of<br />

unity. But it is characteristic of Citarella’s approach that many<br />

of the film’s chapters are told from the perspectives of different<br />

characters and vary wildly in tone. ” <strong>—</strong> LAWRENCE GARCIA<br />

[Published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s NYFF 2022 coverage.]<br />

DIRECTOR: Laura Citarella; CAST: Laura Paredes, Ezequiel<br />

Pierri, Rafael Spregelburd; DISTRIBUTOR: The Cinema Guild; IN<br />

THEATERS: April 21; RUNTIME: 4 hr. 20 min.<br />

GUY RITCHIE’S THE COVENANT<br />

Guy Ritchie<br />

Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant notably marks the first feature that<br />

has included the eponymous filmmaker’s name in the title itself,<br />

a rather curious development as the film is the least Guy<br />

Ritchie-esque movie in his entire filmography. Indeed, the final<br />

product plays more like the director’s attempt at aping the style<br />

of Peter Berg, a slab of right-wing militaristic propaganda that<br />

manages the miracle of making Lone Survivor look subtle in<br />

comparison. Perhaps an even more stunning discovery is that<br />

The Covenant is entirely a work of fiction, its far-flung story of<br />

the brotherhood’s bonds forged in the hells of combat so<br />

relentlessly cliched that it seemed all but a lock for<br />

based-on-a-true-story status. That makes the script, courtesy of<br />

Ritchie and co-writers Marn Davies and Ivan Atkinson, nearly<br />

impossible to forgive in both its mind-numbing predictability and<br />

<strong>—</strong> to be quite frank <strong>—</strong> outright stupidity.<br />

Jake Gyllenhaal, in pure paycheck mode, stars as John Kinley, a<br />

Sergeant Major of the American Army who, in the year 2018, is<br />

stationed in Afghanistan, where he and the various members of<br />

his troop are hunting down Taliban-deployed IEDs. The various<br />

soldiers under Kinley’s command are introduced with on-screen<br />

text, and in such quick succession that it is all but impossible to<br />

make heads-or-tails of who is who. Not that Ritchie is remotely<br />

interested in these men, as most aren’t even afforded a single<br />

character trait <strong>—</strong> although, in fairness, one of them does like to<br />

eat and talk about food. Entering this tight-knit group is Ahmed<br />

(Dar Salim), a no-nonsense Afghani interpreter with whom Kinley<br />

forms an eventual bond because they are both stubborn and,<br />

damn it, they have to respect that in one another. But a raid on<br />

an IED manufacturing plant soon leaves the entire troop dead,<br />

save for Kinley and Ahmed, who must travel by foot over<br />

treacherous terrain to reach base as they are relentlessly hunted<br />

by the Taliban.<br />

It’s at the halfway point in the film that Kinley becomes injured to<br />

the point of catatonia, with Ahmed dragging <strong>—</strong> and, with the<br />

eventual aid of a wagon, wheeling <strong>—</strong> Kinley’s lifeless body over 50<br />

miles to safety, an impossible feat that the film devotes less than<br />

fifteen minutes to detailing, opting for a series of montages (set<br />

to a bombastic and ultimately oppressive score courtesy of<br />

Christopher Benstead) that robs the movie of anything<br />

resembling tension while also completely neutering Ahmed’s<br />

Herculean task. Cut ahead seven weeks, and Kinley discovers<br />

from the safety of his home in California that Ahmed is #1 Most<br />

Wanted on the Taliban’s kill list, a fact that has forced the<br />

interpreter, along with his wife and newborn baby, into hiding.<br />

The remainder of The Covenant focuses on Kinley’s attempts to<br />

locate Ahmed and his family and secure their safe passage to<br />

America, with Sergeant Major ultimately traveling to Afghanistan<br />

once more in the name of brotherhood, because, of course.<br />

The film’s first hour is certainly no great shakes, but it feels like a<br />

downright masterpiece in comparison to the dire second half,<br />

which mostly consists of Gyllenhaal delivering a lot of<br />

long-winded monologues about the importance of paying back<br />

debts while doing his best to look as tough as possible, which<br />

amounts to a dedicated monotone delivery and a catalog of<br />

dead-eyed stares. Much like Ritchie’s last feature,<br />

Mission:Impossible-wannabe Operation Fortune, The Covenant is<br />

completely devoid of any of the stylistic tics that once marked<br />

the director’s work. Some might view this as a sign of<br />

maturation, but such an argument is DOA when the alternative is<br />

just some shaky cam and a palette of browns and grays that<br />

17

FILM REVIEWS<br />

have been bleached and color-corrected within an inch of their<br />

life. Oh wait, Ritchie does this one thing where the camera slowly<br />

zooms in on someone when they are speaking, then it slowly <strong>—</strong> or<br />

sometimes even quickly <strong>—</strong> zooms out again within the same<br />

shot. Spielberg, take notes. Jokes aside, the director utilizes this<br />

move to the point of unintentional comedy, repeated ad nauseam<br />

across the film’s runtime.<br />

Faring no better is Gyllenhaal, who delivers what might be the<br />

worst performance of his career, an approximation of machismo<br />

that feels forced by half. Salim at least brings some much-need<br />

gravitas to a sorely under-written role, but there is no depth to be<br />

found in the characterization, simply archetypes that exist in<br />

service of some good old-fashioned, “America, fuck yeah!” But<br />

wait, maybe there is actually more to this movie. After all,<br />

on-screen text at the film’s end states that Afghani interpreters<br />

who were abandoned upon the U.S.’s withdrawal from the country<br />

in 2021 are still being hunted by members of the Taliban, who see<br />

them as traitors. Perhaps Ritchie is attempting to shed light upon<br />

a horrifying consequence of American imperialism and the<br />

military-industrial complex, using and disposing of those<br />

individuals whose lives the U.S. was supposedly there to protect.<br />

Scratch that: the end credits also include lots of photos of<br />

nameless <strong>—</strong> and in most cases, faceless <strong>—</strong> American soldiers<br />

posing with who we are to assume are Afghani interpreters.<br />

There are even a few smiles here and there. That this all scans<br />

just as profoundly hollow and borderline insulting as everything<br />

else that preceded it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise.<br />

Indeed, there is nary one to be found in this particular Covenant,<br />

Guy Ritchie’s or otherwise. <strong>—</strong> STEVEN WARNER<br />

DIRECTOR: Guy Ritchie; CAST: Jake Gyllenhaal, Dar Salim,<br />

Alexander Ludwig, Antony Starr; DISTRIBUTOR: United Artists; IN<br />

THEATERS: April 21; RUNTIME: 2 hr. 3 min.<br />

CHEVALIER<br />

Stephen Williams<br />

In July 2020, The New York Times published an article by<br />

composer and music composition professor Marcos Balter that<br />

criticized the notion of calling Joseph Bologne “Black Mozart.” A<br />

versatile genius and all-time classical music great in his own<br />

right, Bologne could do better than be reduced in comparison to<br />

an “arbitrary white standard.” Director Stephen Williams’ latest<br />

outing, Chevalier, opens with a concert scene written to<br />

essentially argue that very thing. Bologne, embodied dutifully by<br />

Kelvin Harrison Jr., saunters onstage after Mozart concludes a<br />

song, asking to join him in a duet. He promptly steals the show,<br />

to the crowd’s amazement and Mozart’s consternation. As biopics<br />

go, Chevalier isn’t particularly revolutionary stuff, but there’s a<br />

sincerity in its desire to function as a character study and a<br />

celebration that pushes it past flatly generic territory.<br />

Bologne is the son of a wealthy, white French planter and an<br />

enslaved Black woman. His father dumps him in an academy at a<br />

young age, demanding his son pursue excellence while<br />

abandoning him and the disgrace that he represented. By the<br />

time Harrison Jr. steps into Bologne’s shoes, he’s already a<br />

burgeoning virtuoso and friend of Marie Antoinette (Lucy<br />

Boynton), his sophistication a shield and his arrogance<br />

notorious. When he sets his sights on the vacant conductor<br />

position at the Paris Opera, he taps Marie-Josephine de<br />

Montalembert (Samara Weaving) to sing in the lead role.<br />

Meanwhile, revolution is brewing in France, and Bologne learns<br />

that, while his gifts may elevate him, they aren’t enough to earn<br />

him equal treatment.<br />

Chevalier is fittingly operatic in style, its Paris setting elaborately<br />

curated, the exteriors sun-drenched, interiors candlelit. The<br />

soundtrack kicks in on cue, and the penchant for rotational slow<br />

pans creates an atmosphere that, while never feeling prestige,<br />

has an occasional woozy elegance. And everyone seems to be<br />

having fun in their roles, the period characters always<br />

immaculately dressed, trading barbs Bridgerton-style. But at the<br />

end of the day, Chevalier really is a star vehicle. Bologne is the<br />

only character the script cares to fully realize, and Harrison Jr.<br />

reliably commands in the role. Whether Bologne is poised,<br />

pensive, or pained, Harrison Jr. is diligent in his performance, his<br />

18

FILM REVIEWS<br />

motions deliberate, the range in his voice a weapon. It’s a<br />

tightrope act that could almost be confused for clunky, with how<br />

overt the performative intent can feel, yet it works, both because<br />

Harrison Jr. can be charismatic as hell and because his<br />

approach rings true to this title character: a talented man<br />

embroiled in internal scrutiny in an effort to exist in a world that<br />

reviles him. Bologne is a difficult genius, blessed to be singular,<br />

cursed to be solitary.<br />

Throughout all of this, the specter of the French Revolution<br />

hovers. Characters remark that France is changing <strong>—</strong> proles are<br />

talking about democracy, women are talking about equality,<br />

Black Parisians are publicly visible. Chevalier ties Bologne’s<br />

struggles and ultimate self-actualization with the Revolution’s<br />

radical, liberating promise. It’s certainly not the strongest<br />

subtextual incorporation, perhaps because these threads don’t<br />

significantly connect until it’s time for his climactic middle finger<br />

to the established order that wronged him. Because of this, the<br />

ending reeks of Hollywood-ified great man theory veneration, the<br />

sort that takes viewers out of the film and reminds them that<br />

they’re watching a par-for-the-course, crowd-pleasing biopic.<br />

Then the credits roll, and we learn that once Napoleon took<br />

power, most of Bologne’s works and records were turned to ash.<br />

That’s when Chevalier’s raison d’être becomes clear: crafting a<br />

reliably rousing tale about a long-forgotten figure deserving of a<br />

myth to enshrine his legend. <strong>—</strong> TRAVIS DESHONG<br />

DIRECTOR: Stephen Williams; CAST: Kelvin Harrison Jr., Samara<br />

Weaving, Lucy Boynton; DISTRIBUTOR: Searchlight Pictures; IN<br />

THEATERS: April 21; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 47 min.<br />

GHOSTED<br />

Dexter Fletcher<br />

Dexter Fletcher’s Ghosted is a high-concept romantic action<br />

comedy with movie stars and a decent budget that, were this<br />

2005, would presumably have the potential to be both a hit and a<br />

tabloid item, in the vein of something similar to Mr. and Mrs.<br />

Smith (minus the whole meta matrimony stuff, of course). Now,<br />