InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 10

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

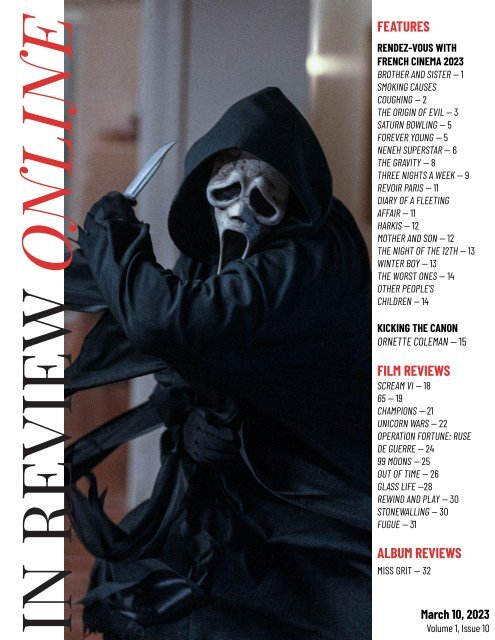

IN REVIEW ONLINE<br />

FEATURES<br />

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH<br />

FRENCH CINEMA 2023<br />

BROTHER AND SISTER <strong>—</strong> 1<br />

SMOKING CAUSES<br />

COUGHING <strong>—</strong> 2<br />

THE ORIGIN OF EVIL <strong>—</strong> 3<br />

SATURN BOWLING <strong>—</strong> 5<br />

FOREVER YOUNG <strong>—</strong> 5<br />

NENEH SUPERSTAR <strong>—</strong> 6<br />

THE GRAVITY <strong>—</strong> 8<br />

THREE NIGHTS A WEEK <strong>—</strong> 9<br />

REVOIR PARIS <strong>—</strong> 11<br />

DIARY OF A FLEETING<br />

AFFAIR <strong>—</strong> 11<br />

HARKIS <strong>—</strong> 12<br />

MOTHER AND SON <strong>—</strong> 12<br />

THE NIGHT OF THE 12TH <strong>—</strong> 13<br />

WINTER BOY <strong>—</strong> 13<br />

THE WORST ONES <strong>—</strong> 14<br />

OTHER PEOPLE’S<br />

CHILDREN <strong>—</strong> 14<br />

KICKING THE CANON<br />

ORNETTE COLEMAN <strong>—</strong> 15<br />

FILM REVIEWS<br />

SCREAM VI <strong>—</strong> 18<br />

65 <strong>—</strong> 19<br />

CHAMPIONS <strong>—</strong> 21<br />

UNICORN WARS <strong>—</strong> 22<br />

OPERATION FORTUNE: RUSE<br />

DE GUERRE <strong>—</strong> 24<br />

99 MOONS <strong>—</strong> 25<br />

OUT OF TIME <strong>—</strong> 26<br />

GLASS LIFE <strong>—</strong>28<br />

REWIND AND PLAY <strong>—</strong> 30<br />

STONEWALLING <strong>—</strong> 30<br />

FUGUE <strong>—</strong> 31<br />

ALBUM REVIEWS<br />

MISS GRIT <strong>—</strong> 32<br />

March <strong>10</strong>, 2023<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1, <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>10</strong>

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA 2023<br />

BROTHER AND SISTER<br />

Arnaud Desplechin<br />

Somewhere along the line, not all that long ago, Arnaud Desplechin ceased to be a marketable<br />

name in the U.S. film biz. While certainly never a properly, consistently lauded figure over here, the<br />

now-62-year-old French auteur and Cannes mainstay has nevertheless found audiences via the<br />

likes of IFC and Magnolia, who put out his last film, Ismael’s Ghost, to get U.S. distribution. That was six years ago now, and in the time<br />

since, Desplechin has released two more features (the misunderstood procedural Oh Mercy! and the pokey, elliptical Philip Roth<br />

adaptation Deception), a television miniseries (En thérapie), and directed (and filmed) a production of Angels in America for<br />

Comédie-Française, though none of these have found their way to American audiences.<br />

It seems excitement has waned for this formerly hip filmmaker, yet little about his approach and voice has changed since his 1996<br />

breakthrough My Sex Life… or How I Got Into an Argument, nor has his stable of actors, an elite crew he largely discovered, boasting the<br />

likes of Matthieu Almaric and Marion Cotillard, which makes the disinterest in getting his recent work distributed here all the more<br />

baffling and frustrating. That said, one can imagine the mischievous, purposefully indulgent self-referentialism of Ismael’s Ghost and<br />

its predecessor My Golden Days to be a turn-off for the uninitiated (they both act as pseudo-sequels to my Sex Life...), compounded by<br />

those films’ mean, unemphasized sense of humor and ironic self-critique; the dry dramatics of Oh Mercy! and Deception operated less<br />

1

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

like an antidote to these potential marketing hurdles, and rather<br />

more like another potential hindrance.<br />

Still, despite these recent setbacks, there’s good reason to<br />

believe that Desplechin could make a grand return to U.S. art<br />

houses and critical favor, and that his latest, Frère et Soeur (AKA<br />

Brother and Sister) could be the film to make this happen.<br />

Premiering in the U.S. thanks to Film at Lincoln Center’s<br />

Rendez-Vous with French Cinema festival, Brother and Sister<br />

bears the filmmaker’s off-kilter sensibility channeled into a<br />

searing domestic drama starring Melvil Poupaud and Marion<br />

Cotillard as the brother and sister of the title, Louis and Alice.<br />

Opening on a pair of tragedies <strong>—</strong> first, a wake for Louis’<br />

(Poupaud) young son, and then an elaborate car accident that<br />

leaves the duo’s parents hospitalized and near death <strong>—</strong> Brother<br />

and Sister skips back and forth through time to fill in the siblings’<br />

backstory and reveal the origins of their oft-referenced hatred<br />

for one another. Although we’re initially lead to believe that the<br />

rift began somewhere around the child’s wake in the opening<br />

scene, Desplechin’s screenplay ends up taking us further into the<br />

past (and then back again to the dreary present), attempting to<br />

get us closer to the truth while never quite allowing us to see the<br />

whole picture.<br />

This narrative approach proves key to Desplechin’s vision for<br />

Brother and Sister which<br />

might have otherwise<br />

been camp-adjacent<br />

high drama, but is<br />

instead redirected<br />

toward a classically<br />

cinematic exploration of<br />

selective memory and<br />

subjectivity (not unlike<br />

My Golden Days, but<br />

without the meta<br />

elements). We are<br />

allowed to glean a<br />

general picture, and by<br />

the film’s conclusion no<br />

grand mystery truly still<br />

persists, but important<br />

plot and character<br />

Details still elude us, especially in the case of the family<br />

matriarch, who remains in a coma for the picture’s duration,<br />

unable to defend herself against accusations of cruelty. Open to<br />

appreciation on a number of different levels, Brother and Sister is<br />

pure Desplechin minus the self-mythologizing, a slight reset that<br />

still maintains the director’s sly humor and destabilizing<br />

approach to sequencing, and featuring two major performances<br />

from Poupaud and (especially) Cotillard, who navigate the film’s<br />

significant tonal shifts with considerable, affecting grace. <strong>—</strong> M.G.<br />

MAILLOUX<br />

SMOKING CAUSES COUGHING<br />

Quentin Dupieux<br />

Reinventing the superhero genre often entails energizing it,<br />

usually with piled-on camp (as with Troma Entertainment’s The<br />

Toxic Avenger and, more recently, Marvel’s Deadpool) or pointed<br />

critique (as with Eric Kripke’s series The Boys). Typically, the<br />

assumption is that the genre needs reinventing because it’s stale,<br />

and staleness is a bad thing. But what of jettisoning staleness<br />

only to restore it? With neither gaudy bloodlust nor dramatic<br />

reversal, Quentin Dupieux’s “Avengers assemble!” moment<br />

collapses upon itself, and deliberately so. A loosely construed<br />

series of wacky vignettes, Smoking Causes Coughing is calibrated<br />

to an uncanny tonal wavelength, entreating<br />

2

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

eavesdroppers to indulge in the simultaneous exhibition of the<br />

comical and the creepy. Think midnight hangout movie, with<br />

quasi-stoner philosophy to boot <strong>—</strong> it’s quite a hoot.There’s literally<br />

a campfire session way past working hours, all for the purpose of<br />

building group cohesion. You see, Dupieux’s protagonists this<br />

time around aren’t some hapless good-for-nothings, bewildered<br />

couples, or killer wheels; they’re the new Toxic Avengers, now<br />

branded <strong>—</strong> in endearingly French fashion <strong>—</strong> as the Tobacco<br />

Force. The quintet of carcinogens (each of them named after one<br />

of cigarette smoke’s sightless killers) don Ultraman-style<br />

costumes, complete with helmets, and they harness the clouds of<br />

their powers for the honorable cause of fighting, no, exploding<br />

evil.<br />

An opening sequence featuring some gawking passers-by<br />

witnesses this task force, headed off-site by a talking,<br />

acid-drooling rat, ganging up on a rubber kaiju tortoise. With<br />

cheeky Gallic irreverence (the playful banter of early Godard with<br />

the tongue-in-cheek setup of the OSS 117 films), they finish him<br />

off, rinse clean, and head off to a work retreat, the bane of<br />

modern capitalism. Camped by a picturesque river and stocked<br />

with supplies <strong>—</strong> a minimart with live-in assistant included <strong>—</strong> from<br />

an über-sleek underground bunker, Ammonia (Oulaya Amamra),<br />

Benzene (Gilles Lellouche), Mercury (Jean-Pascal Zadi), Methanol<br />

(Vincent Lacoste), and Nicotine (Anaïs Demoustier) thus prep for<br />

their next episode by exchanging horror stories, the stuff of<br />

nighttime and existential terrors.<br />

There’s a Thinking Helmet sometime from the 1930s, Cartesian<br />

dissociation by way of possible Nazi etiology; a grisly swimming<br />

pool murder featuring Adèle Exarchopoulos as a voluptuous<br />

housewife; bodily dissociation via grape presser; ecological<br />

statement cursorily received; as well as <strong>—</strong> to justify its superhero<br />

veneer <strong>—</strong> the impending threat of global extermination, courtesy<br />

of alien malevolence. But Smoking Causes Coughing also isn’t<br />

quite the superhero flick it’s billed as; the loopy director’s<br />

sensibilities, here, are trained more toward the superhero<br />

anti-movie, with or without political intent. It could be had that<br />

the eponymous proposition be taken as less-than-subtle slight<br />

against the empty calories of banal military-industrial addictions,<br />

sponsored by Feige, Marvel, and Co. It could also be a converse<br />

extolling of simple-life virtues: have a smoke in France and drift<br />

back to Cold War nostalgia, where bodies and minds<br />

were, relative to today and, for the most part, freer to think,<br />

make love, procreate.<br />

That the bulk of the film’s comic horror hinges on some physical<br />

mishap, played out to (eagerly expected) absurd proportions, is<br />

probably no accident. “God is a smoker of Havanas,” croons Serge<br />

Gainsbourg over the title cards; your penchant for coughing,<br />

then, relies on how much you believe in Him, or vice versa. As a<br />

standalone feature, this already rocks, but further contextualized<br />

against whatever capeshit dreck your local cineplexes are<br />

putting out, Smoking Causes Coughing is a quietly potent banger.<br />

<strong>—</strong>MORRIS YANG<br />

THE ORIGIN OF EVIL<br />

Sebastien Marnier<br />

Sebastien Marnier’s latest breezy, twisty thriller The Origin of Evil<br />

may lack any deeper interrogation in its Agatha<br />

Christie-reinvention of deception, but its strong ensemble cast<br />

makes the endeavor worthwhile, if not substantial, viewing.<br />

Stéphane (Laure Calamy), a worker at a fish cannery, rediscovers<br />

the family who gave her up at birth, reaching out to her father<br />

Serge (Jacques Weber), vague as to whether she is seeking<br />

connection or waiting for his grave to be dug. Though the women<br />

around him try to hide it, Serge is in poor health, and though<br />

nothing is as it seems, it's the perfect setup for Victorian<br />

melodrama. Wary of Stéphane’s arrival, his wife Louise<br />

(Dominique Blanc) and daughter George (Doria Tiller) are prone to<br />

quips, long drags from cigarettes, and and a view of life that is<br />

mostly through a camera lens <strong>—</strong> more playing pieces in a bored<br />

game of middlebrow intrigue. Serge’s home is one fit for a Bond<br />

villain <strong>—</strong> an impersonal setting that seems more fit to be ogled<br />

for its production design aesthetics than its enhancement of<br />

dull-bladed gameplay <strong>—</strong> in stark contrast with his long-lost<br />

daughter’s shared apartment. There are family fights and lines<br />

drawn by class and generation, but in the end, formula and<br />

structure win every argument.<br />

If anything, the roll of the dice in Clue more closely recalls<br />

François Ozon’s campy murder mystery 8 Women than it does<br />

2022’s popular Glass Onion. Here, though the background of<br />

Stephane’s class and sexuality inform her character, Marnier is<br />

similarly more concerned with the icons of genre than he is the<br />

3

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

messaging of his familial power struggle. The family in The Origin<br />

of Evil is largely made up of caricatures: the ever-watchful maid,<br />

the restless teenager, the dubious executor. These are individual<br />

women less primed for social commentary, and more cast to<br />

fulfill genre tropes. Though often frothy, Marnier isn’t unaware of<br />

those present tropes, frequently casting a wink toward a secret<br />

passageway or rack of sharpened knives. The whodunnit-style<br />

caper is often even presented in split screen, The Talented Ms.<br />

Ripley by way of de Palma, a scrolling gallery of suspects in a<br />

family game night of deception. Calamy is as delightful as usual,<br />

her everywoman character brightened by her customary<br />

rom-com-forged optimism (though not quite the delight of a<br />

summer crowd pleaser like My Donkey, My Lover & I). The dynamic<br />

between Stéphane and her father is particularly strong, given<br />

their situation as mysteries to each other and her feeling the<br />

need to lie to increase her social standing. Does she claim that<br />

she owns the cannery simply to be perceived as closer in class<br />

status, or is the dynamic of a disapproving father she never had<br />

already trickling into her considerations?<br />

The broader class dynamic, however, is somewhat light on<br />

nuance. In the vein of popular recent releases like Parasite, the<br />

dichotomy between the bourgeois family and factory worker,<br />

with Stéphane representing the proletariat, is limited to two<br />

polarized ends only maneuverable via the absorption of the<br />

family unit. The populist sentiment in this recent wave of<br />

class-metaphor genre films frames every conflict as a simple<br />

good versus evil; the wealthy are cartoonishly evil and the<br />

4

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

working class, even when conniving, are good at heart. In what is<br />

often functionally airplane fodder, the disparity between the<br />

characters in itself is not enough conflict, and there must always<br />

be a stark villain in the equation. The Origin of Evil does muddy its<br />

waters a bit, with the addition of Stéphane’s girlfriend (Suzanne<br />

Clement), who’s currently serving a five-year prison sentence.<br />

The relationship between the two women serves to counteract<br />

the façade of a perfect liar driven only by necessity, and the<br />

film’s queerness is a pleasant surprise even if it isn’t textually<br />

central. But where the film’s greatest benefit comes from its<br />

particular context: French commercial cinema tends toward the<br />

most trying forms of comedy <strong>—</strong> see, for example, the popularity<br />

of the insufferable Astérix & Obélix franchise <strong>—</strong> so the self-aware<br />

genre homage of The Origin of Evil is much welcome, even if it<br />

doesn’t break any new ground.<strong>—</strong> SARAH WILLIAMS<br />

SATURN BOWLING<br />

Patricia Mazuy<br />

Patricia Mazuy, now six films deep in a three-decade-plus career<br />

with Saturn Bowling, has always risked a certain, tantrum-centric<br />

filmmaking, favoring characters with shared psychoses who butt<br />

heads with one another and all those around them. She alienates<br />

via general unpleasantness, but it’s even more rewarding to<br />

penetrate those barriers and discover the primalness that<br />

charges her work. In a filmography populated by violent<br />

burnouts, obsessives, and the like, Saturn Bowling still earns the<br />

distinction of being her most male film.<br />

A pair of mildly estranged half-brothers, Armand (Achille<br />

Reggiani) and Guillaume (Arieh Worthalter), tenuously reunite<br />

following their father’s death, when it comes time to decide<br />

ownership of the family’s beloved, subterranean bowling alley.<br />

The former is effectively unhoused, spending his nights at his<br />

club security job after everyone’s left; he’s also desperate for sex,<br />

ogling any and all exposed flesh, masturbating in the rain,<br />

deploying failed pickup lines. Guillaume, too busy with his police<br />

work, offers the bowling alley to Armand, who also gets their<br />

father’s opulent apartment, decked out with snakeskin jackets,<br />

hunting trophies, rifles, and a German Shepard. It’s not long<br />

before Armand, his lack of self-control already telegraphed,<br />

commits a murder or two.<br />

Mazuy attempts an impressive gambit of divided perspectives,<br />

Armand’s unsettlingly impressionistic subjectivity shifts to a<br />

more procedural temperament after that first shock of violence.<br />

The first murder explains the rest, and thus, we’re only subjected<br />

to one interval of absolutely misogynistic depravity; to achieve<br />

restraint, Mazuy indulges just once. Guillaume has to shoulder<br />

that moral weight of suspecting his half-brother, while<br />

navigating the vicissitudes of his own life. The film admittedly<br />

loses momentum as it mounts toward a more straightforward<br />

climax that isn’t exactly expected from the prologue’s<br />

disorienting visual and aural excisions, where the dramatic<br />

development lumbers along in a gait similar to the seething<br />

Armand. Perhaps if Saturn Bowling were intent on a more equal<br />

alternation between brothers, as in 1989’s Thick Skinned, it would<br />

play as less mismatched than it ultimately is. Thankfully, then, at<br />

least, the muscle of this experiment is still commendable enough<br />

in and of itself, leaving plenty enough to chew on despite some<br />

notable imbalance. <strong>—</strong> PATRICK PREZIOSI<br />

FOREVER YOUNG<br />

Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi<br />

The latest film from French actor-director Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi<br />

is difficult to evaluate. One could argue that, for what it is, it is<br />

fairly accomplished. A showcase for mostly young talent,<br />

including some performers making their film debut, Forever<br />

Young is exuberantly melodramatic, the film’s form matching its<br />

protagonists’ heightened emotions and desperation to be<br />

understood. I suspect that a certain kind of viewer might well<br />

find Bruni-Tedeschi’s film swoony and romantic, a full-throttle<br />

tribute to the heedlessness of young adulthood.<br />

All of which is to say that Forever Young is two solid hours of<br />

theater-kid energy, a film that wholeheartedly believes that the<br />

art of acting is a beautiful, agonized, possibly holy mission, and if<br />

(like me) you don’t exactly subscribe to that ideology, this is an<br />

incredibly irritating film. Its French title, Les Amandiers, refers to<br />

a real-life theater studies program that Bruni-Tedeschi herself<br />

took part in in the late 1980s, one that was led by legendary film<br />

and stage director Patrice Chéreau (here played by the<br />

omnipresent Louis Garrel). But the English title, probably<br />

intended as a celebration of the freedom of youth, actually<br />

betrays a deep investment in arrested development.<br />

5

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

This is an autobiographical work, but one that is entirely<br />

self-serving and ego-driven, the sort of thing you might expect if<br />

Glee’s Rachel Berry were a real person and got the chance to<br />

vomit her blinkered worldview onto the silver screen. Lead<br />

character Stella (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), like the director herself, is<br />

a child of enormous privilege. I don’t know exactly how<br />

accurately Forever Young reflects Bruni-Tedeschi’s own<br />

upbringing. Whether she, like Stella, grew up in an upper-class<br />

compound and had a butler (Franck Demules) for a surrogate<br />

parent, I can’t say. But it’s hard to ignore the rather flattering<br />

self-portrait Stella represents. Like the director, she is blonde,<br />

with piercing blue eyes, and <strong>—</strong> in the film’s dramatic universe <strong>—</strong><br />

almost everyone is dying to sleep with her.<br />

To be fair though, practically everyone is screwing everyone else<br />

in this demimonde, but most of the focus is on Stella’s benighted<br />

relationship with Étienne (Sofiane Bennacer), the “bad boy” of the<br />

theater class who is intermittently homeless and consistently<br />

hooked on heroin. Bruni-Tedeschi asks us to understand these<br />

young performers’ dissolute personal lives not as a hindrance to<br />

their art but as its spiritual fuel. Method acting is a fetish, and<br />

possibly a cult, in that it assumes that theatrical creation is<br />

borne only from torment, the demand to push one’s behavior<br />

beyond the borderline of rationality. Industry actors live for this<br />

stuff, which is why they love to bestow awards on their peers for<br />

conspicuous suffering <strong>—</strong> losing or gaining 50 lbs., consuming<br />

raw bison liver in subzero conditions, or “bravely” abandoning<br />

glamor in favor of disconcerting ordinariness, with split ends and<br />

bad teeth.<br />

A few years ago, Robert Pattinson made a shrewd observation.<br />

“You only ever see people doing method when they’re playing<br />

anasshole,” he remarked. “You never see someone just being<br />

lovely to everyone going, ‘I’m really deep in character.’” In a way,<br />

Forever Young is a tribute to precisely this kind of asshole<br />

behavior as well as to a coterie of performers for whom tedious<br />

solipsism <strong>—</strong> the fundamental state of being for middle-class<br />

white people in their early twenties -- is treated as the<br />

precondition for a visionary avant-garde. In Bruni-Tedeschi’s<br />

precious bubble, the loss of loved ones and even the AIDS crisis<br />

are little more than affect-fodder, a set of emotional memories<br />

that seize these children and then quickly dissipate, all to ensure<br />

that the show will go on. <strong>—</strong> MICHAEL SICINSKI<br />

NENEH SUPERSTAR<br />

Ramzi Ben Sliman<br />

Ballet school drama Neneh Superstar is the kind of film that gives<br />

festivals like Rendez-Vous with French Cinema a reason to reach<br />

out to younger teens like they do with the film’s initial free<br />

6

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

screenings. While it’s YA in scope, Neneh-Fanta Gnaoré’s (Oumy<br />

Bruni Garrel) story <strong>—</strong> directed by Ramzi Ben Sliman <strong>—</strong> is both<br />

heartfelt and bitterly honest about the truth behind so many<br />

lauded institutions. She dreams of becoming a ballet dancer,<br />

something that shows in her every movement on the playground,<br />

teeming with energy. Dreaming of the Opera de Paris Ballet<br />

School, she hasn’t quite contended with the precise nature of<br />

that school’s mission. Her supportive parents (Steve Tientcheu<br />

and Aïssa Maïga) encourage this dream, though her working-class<br />

background outside of Paris puts her at odds with the wealthy<br />

student body of young ballerinas with private tutors, and that’s<br />

well before race comes into play. Even once she’s admitted, just<br />

one of seven girls in a vast sea of hopefuls, school head Marianne<br />

Belage (Maïwenn) reminds her that she is here to be challenged <strong>—</strong><br />

which is a lot of weight to put on a child’s shoulders.<br />

Garrel, in her first role in a feature not directed by one of her<br />

actor-director parents, often comes off as a bigger star than the<br />

rising talent she plays. She's incredibly kinetic, always in motion<br />

even when preteen restlessness hurdles away from a dancer's<br />

grace; cocky and not quite in control of her own growing body. A<br />

young performance can make or break a film, and her<br />

commitment means that her wide-eyed admiration for a director<br />

she wants to be her mentor and the power struggles that<br />

subsequently ensue between student and teacher make the two<br />

parties into equals in their intensity.<br />

From an American perspective, the overt nature of the school’s<br />

institutional racism seems a bit overtly presented, but the<br />

cultural difference does prevent more covert forms of prejudice<br />

from taking the lead. When filling out applications, the girls are<br />

reminded to list many details about their parents, down to height<br />

and weight (in order to extrapolate the not-yet-grown children’s<br />

physical development, and therefore, their worthiness), which<br />

serves as a reminder that they do not get to leave their<br />

backgrounds behind for their talent. Aggressors are punished<br />

less severely than Neneh when she finally fights back, and she is<br />

admonished by being blatantly excluded from a chance to lead in<br />

the class production of Snow White. Marianne subscribes to a<br />

7

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

belief in “guaranteeing the tradition of white ballet,” and even<br />

when she admits to relating to the young girl’s struggle for<br />

perfection, she is still distanced by her own prejudice. But Neneh<br />

herself is never painted as a perfect victim in this situation. She’s<br />

often rude and distracted and interrupts because she’s twelve <strong>—</strong><br />

a child forced into adult games.<br />

This film also features one of the most eye-roll-worthy needle<br />

drops imaginable. Perhaps Sliman hasn’t been inundated with<br />

years of repetitive TikTok, but Masked Wolf’s “Astronaut in the<br />

Ocean” is too new to be divorced from its own virality, even if it<br />

may genuinely be what a twelve-year-old would dance to for fun.<br />

At times, the ballet world also seems so cold and unwelcoming<br />

that you’d wonder why she, with all her flair for performance,<br />

would desire it for anything beyond the mausoleum-cold image<br />

of pain and success <strong>—</strong> the transfixion isn’t effectively articulated.<br />

And so, though Neneh Superstar boasts some young talent, and<br />

the first truly great performance from Maïwenn since 2016’s My<br />

King, it seems best suited to be an awakening for a younger<br />

audience rather than any more substantial interrogation into<br />

persisting, insidious power structures. <strong>—</strong> SARAH WILLIAMS<br />

THE GRAVITY<br />

Cédric Ido<br />

There are strange goings-on in the Stains suburbs of France, an<br />

assemblage of stark high-rise buildings that are home to a<br />

collection of everyday working-class people, the elderly, and rival<br />

gangs of drug dealers looking to consolidate their control over<br />

the area. Christophe (Jean-Baptiste Anoumon) has just been<br />

released from a three-year prison stint and returns home to find<br />

that things have changed. His estranged childhood friends,<br />

brothers Daniel (Max Gomis) and Joshua (Steve Tientcheu), are<br />

dealing on the sly, hoping not to run afoul of the “Ronin,” a roving<br />

pack of wild teenagers who have declared themselves masters of<br />

the entire housing project. As someone explains to Christophe,<br />

these kids are different <strong>—</strong> disinterested in money, and with no<br />

official leader, they are instead concerned with fairness and<br />

equality, although they’ll employ violent means to maintain their<br />

dominance. Much of the first half of the film charts these various<br />

shifting dynamics; Daniel is about to leave the country with his<br />

girlfriend and child to move to Canada, but can’t bring himself to<br />

tell Joshua or his running coach. Joshua is an inventor in his<br />

8

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

free time, tricking out his wheelchair to hide drugs from the<br />

Ronin and tinkering with something or other in the basement of<br />

his building. Christophe thinks the Ronin dropped a dime on him<br />

to get him out of the way, and wants to rob their stash houses to<br />

get recompense for his time served. An aura of potential violence<br />

hangs over every scene, as various encounters threaten to<br />

tumble over from loaded conversation to outright warfare.<br />

This is largely the stuff of “cinéma de banlieue,” a familiar genre<br />

of French cinema charting life in these suburban spaces typically<br />

home to the poor and immigrants. Writer/director Cédric Ido,<br />

himself French Burkinabe, knows the milieu well. But if The<br />

Gravity begins as something akin to La Haine, it gradually<br />

transforms into something much odder, and more interesting.<br />

Because while these characters act out their interpersonal<br />

conflicts, a strange cosmological event begins taking shape. Ido<br />

allows details to creep in slowly at first, mostly via TV news<br />

broadcasts emanating from the background; the planets are<br />

slowly converging in a once-in-a-lifetime happening, and<br />

commentators disagree on what, if any, effects this convergence<br />

might have on the Earth. Meanwhile, Ido and cinematographer<br />

David Ungaro slowly complicate the visual scheme of their film.<br />

Brief cutaways track the slow movements of various celestial<br />

bodies, while drone shots of the banlieue skyline take on the<br />

portentous dread of the long Steadicam shots in The Shining. The<br />

film slowly drains the life out of the banlieue until it seems<br />

populated only by the main characters and a seemingly endless<br />

number of Ronin, who have been driven mad by the convergence.<br />

Ido, a self-confessed “fanboy,” seems determined to expand his<br />

narrative into increasingly strange, genre-adjacent digressions.<br />

There are comic book-style transitions between scenes, while<br />

the Ronin seem plucked from Walter Hill’s The Warriors. Things<br />

eventually deteriorate into outright horror territory, while an<br />

action sequence late in the film seems inspired by the<br />

concussive, blunt object-head trauma choreography favored by<br />

South Korean action movies (and the Oldboy hammer fight in<br />

particular). Even anime elements make an appearance, with a<br />

mech-like contraption that appears in a fist-pumping moment of<br />

triumph. It’s all very exciting, and while Ido risks absurdity with<br />

his disparate influences, he’s so gleefully committed to his<br />

scenario that it all somehow manages to work. It remains to be<br />

seen what kind of adventurous distributor might take a chance<br />

on such a strange, willful genre hybrid, or how they would even<br />

market it to an unsuspecting audience. But it’s a remarkable film,<br />

thrillingly unpredictable and even beautiful in its own way. Ido is<br />

a major talent, that’s for sure. We need more films like The<br />

Gravity, willing to bend and shape genre to its own idiosyncratic<br />

ends. In this sense, at least, it bears a resemblance to Clement<br />

Cogitore’s Sons of Ramses, another nocturnal excursion into the<br />

underbelly of French society. Make seeking this film out a<br />

priority. <strong>—</strong> DANIEL GORMAN<br />

THREE NIGHTS A WEEK<br />

Florent Gouëlou<br />

Three Nights a Week is less the love story between a straight man<br />

and a drag queen it has been billed as, and rather a love letter to<br />

a subculture and the invitations that it opens. Photographer<br />

Baptiste (Pablo Pauly) is ostensibly straight. He visits a World<br />

AIDS Day awareness event that his girlfriend Samia (Hafsia Herzi)<br />

is involved with, intending to use some of the local drag scene in<br />

his art. Though he is intrigued by the images of freedom through<br />

performance and the glitter from ashes on an artistic level, one<br />

particular queen does catch his eye. Cookie Kunty (Romain Eck)<br />

is strangely hypnotic and calming, whether through Baptiste’s<br />

eyes or not, and, as she takes a slow, practiced drag of a<br />

cigarette lit, with confidence, by a male admirer; more alluring to<br />

him than she is to Samia, and a reminder of Baptiste’s marriage<br />

to another, matte-r world.<br />

The relationship begins just like so many on screen: a love story<br />

between the idea of a man and the idea of a woman. Only it’s not<br />

long before Baptiste finds himself running into Quentin, the man<br />

behind the magic, and reconciling the reality of a gay<br />

relationship with the larger-than-life partner he has in Cookie<br />

proves hard at first. Even Quentin is shyer without the avatar of<br />

Cookie, hiding painted nails from a server and markedly less<br />

overwhelmed with confidence by his lover’s side. But the “it’s not<br />

guys, it’s just him” (though in this case, it’s just her, to begin with)<br />

excuse is trite and uninteresting even with the genderplay twist,<br />

and Baptiste’s insistence to his girlfriend as their relationship<br />

devolves <strong>—</strong> that this is an exception, not a rule for him <strong>—</strong> may be<br />

sometimes realistic but narratively does feel like conflict invoked<br />

for the sake of romantic complication, somewhat unnecessary<br />

when the leads have chemistry from the start.<br />

9

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

The introduction of Baptiste’s queerness via the avatar of Cookie<br />

Kunty recontextualizes drag not as a final art in visible<br />

queerness, but as an inviting exploratory space for desire. Queer<br />

femininity isn't an object of fear for him, but one of familiarity,<br />

painted not in proximity to heterosexual gender performance but<br />

in homage to it. At the start, he may still be primarily in the world<br />

of heterosexuality, but a few nights a week, starting slowly,<br />

Baptiste is eased into his own desires through his own art. As a<br />

photographer, he is initially stricken by the image of Cookie as<br />

one of purer expression; it’s only a matter of time before he<br />

realizes how closely that image is tied to his own hand. Cookie,<br />

and many of the other queens in the Paris scene, exemplify the<br />

convoluted image of what men are told they should desire in<br />

women. They are gracious yet spirited, curvy yet padded and<br />

corseted in the right places to match an image, confident yet<br />

bound to an audience. It’s no wonder that even the most blazing<br />

personality in the room allows Baptiste the safe space to explore<br />

his queerness: she is what he believes in.<br />

That Baptiste’s wide-eyed wonder at his first queer love is so<br />

authentic, as is the film’s immersion in European drag culture, is<br />

thanks to the first-hand experience of many of the cast and<br />

crew. Director Florent Gouëlou has performed as drag queen<br />

Javel Habibi by night, but he is not alone in his ties to the scene;<br />

Eck’s Cookie Kunty persona has existed for years, and although<br />

Three Nights a Week is a fictionalized story when it comes to<br />

Quentin, Cookie as a stage persona is very much real. This<br />

personal respect for drag as an art form means that the<br />

performance spaces and club scenes hardly feel staged (beyond<br />

a literal one), and the nightlife is vibrant and beautifully lit. The<br />

authenticity is a large part of why the more grounded social<br />

points <strong>—</strong> where the glamorous romance pauses to remind our<br />

lovers of its historical reality: a culture decimated by AIDS and<br />

social homophobia <strong>—</strong> don’t feel out of place, because they are<br />

just as much a mark on the scene as the swept-away romance is.<br />

<strong>—</strong> SARAH WILLIAMS<br />

<strong>10</strong>

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

REVOIR PARIS<br />

Alice Winocour<br />

“But as much as this search for lost memories and joys enables<br />

Mia to both discover hitherto unseen aspects of Paris (notably, in<br />

her search for a Senegalese kitchen worker, she finds herself in<br />

a poor immigrant district) and have a deeper understanding of<br />

other victims’ damaged psyches, forging more intimate bonds<br />

with strangers in the process, the film’s somewhat loose<br />

narrative does not always demonstrate conviction; Paris<br />

Memories’ most tender side isn’t entirely fleshed out organically,<br />

though it’s perhaps more apparent in certain instances… Still,<br />

despite the lack of an entirely taut story, and the sense that<br />

Winocour’s directions remain conservatively rooted in a familiar<br />

sense of mise-en-scène, what does count <strong>—</strong> apart from Efira’s<br />

effectively moving presence <strong>—</strong> is the filmmaker’s gentle tone and<br />

observational approach, both of which help create distance<br />

between the film’s core <strong>—</strong> Mia’s interiority <strong>—</strong> and the clichéd<br />

socio-political intrusions that pepper its narrative.“ <strong>—</strong> AYEEN<br />

FOROOTAN [Originally published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022 Torinto<br />

International Film Fest coverage.]<br />

DIARY OF A FLEETING AFFAIR<br />

Emmanuel Moret<br />

“The flair and flavor of Mouret’s slick style in Diary of a Fleeting<br />

Affair is exactly what he’s been refining for almost two decades,<br />

transforming even the most abstract and almost implausible<br />

scenarios into convincing streams of events without ever slightly<br />

skewing toward an openly naturalistic approach. Through various<br />

modes of verbal and bodily expressions, concise framings,<br />

heightened spatial awareness, brisk music scores, and an<br />

easygoing chemistry between Kiberlain and Macaigne, who prove<br />

convincing in their roles of an incompatible couple <strong>—</strong> Charlotte<br />

as an amiable, open-minded, and playful extrovert to Simon’s<br />

mostly anxious, awkward introvert, physically defined by his<br />

usually dwindled posture (viewed best during a teasing<br />

threesome scene) <strong>—</strong> Mouret delivers both a jovial and surgical<br />

inspection of the moral and philosophical dilemmas inherent to<br />

modern affairs <strong>—</strong>especially those of the middle-aged <strong>—</strong> in<br />

bittersweet dramedy form.“ <strong>—</strong> AYEEN FOROOTAN [Originally<br />

published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022 Cannes Film Festival coverage.]<br />

11

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

HARKIS<br />

Philippe Faucon<br />

“Harkis is pretty much the sort of foursquare historical drama<br />

one would typically associate with Rachid Bouchareb…<br />

Serviceably directed by Philippe Faucon, Harkis chronicles the<br />

final months of the Algerian War, as experienced by the so-called<br />

harkis, those Algerians who signed up to fight on behalf of France<br />

and against the FLN… While there is nothing cinematically<br />

remarkable about Harkis, it makes its point with admirable<br />

economy (it’s a slim 85 minutes) and speaks frankly about a<br />

group of Algerians who were uniquely screwed by the false<br />

promises of colonial history, asked to betray their fellow Muslims<br />

in the name of some higher ideal that, as far as the Gaullists<br />

were concerned, evaporated as soon as these soldiers had<br />

outlived their usefulness.“ <strong>—</strong> MICHAEL SICINSKI [Originally<br />

published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022 Cannes Film Festival coverage.]<br />

MOTHER AND SON<br />

Léonor Serraille<br />

“As the film progresses, these themes become increasingly<br />

hamfisted, as if Serraille is trying to ensure that audiences are<br />

privy to how the internal worlds of her characters are linked.<br />

When the film moves to focusing on Jean, who at this point is a<br />

teenager, we watch as he becomes intimate with a white girl as a<br />

track from Lambarena’s Bach to Africa plays <strong>—</strong> its mixing of<br />

African music with the works of J.S. Bach is laughably on the<br />

nose. Serraille simply can’t help but connect her ideas across the<br />

film’s three parts in clumsily overt manners. Early in the film, we<br />

watch as Rose and her two sons paint each other’s faces and<br />

revel in their time together. But [Serraille is] unhappy with letting<br />

that scene live as its own sublime moment.“ <strong>—</strong> JOSHUA MINSOO<br />

KIM [Originally published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022 Cannes Film<br />

Festival coverage.]<br />

12

FESTIVAL COVERAGE<br />

NIGHT OF THE 12th<br />

Dominik Moll<br />

“The main problem with Night of the 12th is that Moll and<br />

Marchand (adapting a book by Paula Guéna) seem to think their<br />

audience is as incompetent as the police. Every primary theme<br />

of the film is stated outright in the dialogue, to make sure we<br />

don’t miss anything along the way. An insensitive cop remarks<br />

that Clara got around, which prompts the film’s second full<br />

discussion regarding victim-blaming and misogyny. And near the<br />

film’s end, Vivès remarks to a magistrate (Anouk Grinberg) that, in<br />

fact, “all men killed” Clara… These are not dumb ideas. In a sense,<br />

this is the ultimate takeaway from Bruno Dumont’s L’humanité,<br />

and Night of the 12th’s concern with the obsessive psychology of<br />

damaged cops recalls David Fincher’s Zodiac. But those films<br />

understood the power of subtext. Night of the 12th insists on<br />

signposting its every move, to such a degree that Moll doesn’t<br />

seem to really need the viewer at all.<br />

“ <strong>—</strong> MICHAEL SICINSKI[Originally published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022<br />

Cannes Film Festival coverage.]<br />

WINTER BOY<br />

Christophe Honoré<br />

Honoré, in this way, takes an ostensibly personal film and<br />

dresses it up in the polished realism of less distinctive directors<br />

like Audiard or Sciamma… Instead, the incidents Honoré<br />

highlights are outgrowths of Lucas’s transmuted emotions: he’s<br />

aloof with his friends, overshares with hook-ups, and<br />

possessively tries to seduce his brother’s boyfriend. None of<br />

these threads culminate; rather, the film ascends into<br />

near-tragedy and schmaltz. As a portrait of grief that avoids<br />

extremes, Winter Boy is tasteful to a fault. We can see that,<br />

denied the normative rite-of-passage markers of<br />

late-adolescence, Lucas is casting about for something new to<br />

aim for: he seems to have no particular interests of his own, nor<br />

does he want to adopt those of the people around him. To<br />

surround this chaos with near-diagnostic maturity is less a<br />

useful balance on the part of Honoré, and more a stodgy<br />

mischaracterization.<br />

<strong>—</strong> MICHAEL SCOULAR [Originally published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022<br />

TIFF coverage.]<br />

13

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA<br />

THE WORST ONES<br />

Lise Akoka<br />

“But the neighbors who refer to the film’s cast as ‘the worst ones’<br />

are less concerned with the exploitation of the actors than with<br />

that of their own image. They are more concerned with attracting<br />

more wealthy residents to the neighborhood than they are the<br />

wellbeing of kids like Lily or Ryan who they actively spurn. If<br />

anything, the set, for all its questionable ethical practices,<br />

provides something of an escape from reality and a new, fulfilling<br />

experience for Lily and Ryan. This is especially true when the<br />

scope of the set expands outward from the director to include<br />

the crew who are more friendly and down to earth with the kids,<br />

providing them with more helpful guidance and encouragement.<br />

The Worst Ones finds its groove by rejecting both the neighbors’<br />

scorn for these kids and Gabriel’s artistic pity, showing Lily and<br />

Ryan in a more varied, lifelike light, unbound by the expectations<br />

placed on them by others or a camera. And Wanecque and<br />

Mahaut are terrific playing what amounts to a dual role each;<br />

they’re easily the best thing about the film.“ <strong>—</strong> CHRIS MELLO<br />

[Originally published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2022 Cannes Film Festival<br />

coverage.]<br />

OTHER PEOPLE’S CHILDREN<br />

Rebecca Zlotowski<br />

“Told entirely without the expected, more dramatic (louder)<br />

moments. Music cues rise or cut in earlier than expected, a<br />

whole scene can fade to black, or a conversation won’t be<br />

audible until it’s in the aftermath of conflict. This strategy gives<br />

the characters privacy, and lends more weight to the subtleties<br />

of performing reflection rather than action. In particular, the use<br />

of Vivaldi’s ‘Mandolin Concerto in C Major’ becomes a Kramer vs.<br />

Kramer nod, intentionally signaling memories of more conflictdriven<br />

relationships. Further, by choosing to frame this narrative<br />

<strong>—</strong> in which multiple relationships, large and small, enter and<br />

change and leave Rachel’s life <strong>—</strong> through its emotional aftermath,<br />

Zlotowski bends what would otherwise be a simple falling-inlove-then-out-of-love<br />

story into a character study of a woman<br />

whose every desire is complicated by life itself. In other words,<br />

this is a narrative that should be a melodrama… And yet, this isn’t<br />

that; with the leisure of a Sautet or Rohmer drama, the best<br />

character moments come packaged in peaceful performance,<br />

rather than affective outbursts.“ <strong>—</strong> SARAH WILLIAMS [Originally<br />

published as part of <strong>InRO</strong>’s 2023 Sundance Film Festival coverage]<br />

14

KICKING THE CANON<br />

OF HUMAN FEELINGS<br />

Ornette Coleman<br />

There is perhaps no bolder album title in all of 20th century music than Ornette<br />

Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come. And what’s more, it was entirely appropriate:<br />

Coleman’s arrival in New York City in 1959, followed shortly after by the record’s<br />

release, sent shockwaves throughout the jazz world. There were plenty of doubters<br />

who dismissed Coleman’s innovations as a fad, an affront to jazz tradition, but the<br />

test of time has proven that record’s wild proclamation to be true. There’s<br />

actually a shared theme among most of Coleman’s early album titles<br />

(Tomorrow Is the Question, Change of the Century) that, correctly,<br />

positions the jazz provocateur as a progressive force in the genre’s<br />

development <strong>—</strong> as well as a figure oriented toward the future. Crucially,<br />

though, Coleman’s music also has deep ties to the past. Consider a<br />

record like 1969’s Ornette at 12 <strong>—</strong> again, the title signals a focus on time,<br />

but going in the opposite direction. Ornette at 12 tapped into not only the<br />

music of Coleman’s youth (though that is a permanent consideration,<br />

too), but the uninhibited intuitiveness of being a child <strong>—</strong> a notion<br />

supported by the decision to have his then-12-year-old son, Denardo, on<br />

drums. Denardo would grow into a formidable player as an adult, but he was<br />

clearly an amateur in 1969 <strong>—</strong> and, indeed, his youthful abandon is more or less the<br />

point. Coleman may be commonly regarded as a forward-looking innovator, but to<br />

fully understand his work, one must also recognize its debt to the past <strong>—</strong> both in a<br />

historical and a personal sense. And there may be no better way to come to that<br />

understanding than to examine a less heralded period of Coleman’s career,<br />

which began around 1975 with the formation of his first electric band, Prime<br />

Time.Listening to Prime Time with 21st-century ears, the music still sounds a<br />

good deal more radical, more outlandish than Coleman’s ’60s quartet<br />

masterpieces. By the mid-’70s, the jazz fusion movement was in full swing, but Coleman’s<br />

electric jazz had little in common with Weather Report, Return to Forever, Mahavishnu<br />

Orchestra, or any of the other groups that sprung up in the wake of Miles Davis’ adoption of<br />

electric a half-decade earlier. Even today, there’s hardly any music that sounds like what<br />

Coleman was doing with Prime Time. The closest resemblance can probably be found in some<br />

of the more funk-inspired groups from the downtown New York no-wave scene, but none of<br />

those bands really approach the complexity and abstraction of Coleman’s outfit, nor do they<br />

embody its improvisational principles (and, of course, Prime Time anticipated no-wave by two<br />

or three years).<br />

Part of Prime Time’s uniqueness can be attributed to its unusual instrumentation. The typical<br />

lineup featured an arrangement that remains uncommon today: two electric guitarists, two<br />

electric bassists, two drummers, and Coleman on alto sax (with occasional trumpet and violin<br />

15

KICKING THE CANON<br />

digressions), weaving his way in and out of that supersized<br />

rhythm section. But that’s not all that sets the group’s music<br />

apart. The free approach that typified Coleman’s ’60s work is still<br />

intact here, but it’s been expanded, developed into an<br />

all-encompassing philosophy that the jazz iconoclast called<br />

“harmolodics.” The precise definition of that term is notoriously<br />

difficult to pin down, but it’s an approach that’s predicated on<br />

non-hierarchy: not just the freedom of each individual to<br />

improvise at all times, but the privileging of each aspect of music<br />

(melody, harmony, rhythm, etc.) equally. In practice, it’s<br />

profoundly elastic <strong>—</strong> Coleman’s music can be frenetic, often<br />

feeling like it’s on the verge of descending into total chaos,<br />

though it never does. The free jazz revolution that Coleman<br />

sparked would inspire all sorts of anarchic improvised music all<br />

over the world (plenty of it quite good), but within his own band,<br />

his empowerment of the individual never came at the expense of<br />

a collective unity. The music bends and contorts and, at times,<br />

threatens to burst apart, but that amorphous whole always<br />

remains intact. Prime Time, then, was where that magical<br />

symbiosis reached its apogee <strong>—</strong> and of their six studio records,<br />

it’s probably 1982’s Of Human Feelings that best represents the<br />

group’s essence.<br />

“For all the emphasis on<br />

Coleman’s genius, the<br />

importance of his collaborators<br />

can’t be understated, and he<br />

would be the first to admit it.<br />

As suggested earlier, Coleman is fascinating not just for the way<br />

he looks forward, but also for the way he looks to the past. For an<br />

example of this, look no further than Of Human Feelings' opener,<br />

“Sleep Talk,” which revolves around a call-and-response motif<br />

that quotes the famous bassoon melody from The Rite of Spring.<br />

It’s a playful reference, but one that also carries quite a bit of<br />

meaning, especially when one remembers that Stravinsky<br />

himself borrowed that melody from Lithuanian folk music. One of<br />

Coleman’s peculiar contradictions is that even while his formal<br />

approach is so progressive, his playing is rooted firmly in the<br />

antiquated blues and R&B with which he grew up. His melodies<br />

tend to be simple, easily singable, at times even resembling<br />

childish nursery rhymes, but by working them through his<br />

harmolodic framework, these relics of the past are given a<br />

radical new context, and thus transfigured. One can’t help but<br />

think of Stravinsky and Coleman as parallel figures in some<br />

respects <strong>—</strong> The Rite of Spring itself is a work that draws on<br />

traditions of the past (folk art, pagan ritual) to fuel its innovative<br />

modernism, and, indeed, the riotous reception that greeted its<br />

premiere in Paris is not unlike the uproar that ensued in<br />

response to Coleman’s controversial residency at the Five Spot in<br />

1959. As for the jazz giant’s own past, it’s invoked on “What Is the<br />

Name of That Song?” which reworks a refrain from his 1972<br />

symphony, Skies of America. What was once a dense cacophony<br />

of strings is reborn as a loose, danceable piece of avant-garde<br />

funk. And this sort of thing is an extremely common practice for<br />

Coleman: 1977’s Dancing in Your Head, the first Prime Time album,<br />

similarly borrows a theme from Skies and repurposes the melody<br />

as a motif throughout the entire record, in the process stretching<br />

and manipulating it until it becomes something totally new. On Of<br />

Human Feelings, this strategy speaks to the would-be<br />

disjunctions that lie at the heart of Coleman’s work, and the<br />

effect is one of collapsed boundaries <strong>—</strong> temporal, tonal,<br />

rhythmic, interpersonal. Old-fashioned bluesy melodies collide<br />

with hard funk basslines, West African polyrhythms manifest as<br />

quasi-disco beats; the spirits of Charlie Parker, Igor Stravinsky,<br />

and a younger Ornette Coleman mingle together as one. And<br />

always, there’s present-day Ornette at the center, gently guiding<br />

these disordered fragments into a cohesive synthesis.<br />

For all the emphasis on Coleman’s genius, the importance of his<br />

collaborators can’t be understated, and he would be the first to<br />

admit it. This can be illustrated easily by listening to the records<br />

that precede The Shape of Jazz to Come: his playing and<br />

principles are essentially the same, but, with the exception of<br />

Don Cherry, his bandmates, skilled as they were, just weren’t on<br />

his wavelength. It wasn’t until he and Cherry hooked up with<br />

Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, and Ed Blackwell in the late ’50s that<br />

Coleman’s style was able to flourish. All of those figures were<br />

masterful musicians, but just as important was their willingness<br />

to embrace his unorthodox approach. And the results speak for<br />

themselves.<br />

The Prime Time generation went even further in their devotion to<br />

Coleman, and in their commitment to unlearning the restrictions<br />

16

KICKING THE CANON<br />

they’d been taught. By this time, the dynamic within the band<br />

had shifted to something resembling a guru and his pupils.<br />

Coleman’s new cohort was quite a bit younger than him, with<br />

some of them, like drummer Grant Calvin Weston and bassist<br />

Jamaaladeen Tacuma, still being teenagers when they joined.<br />

And, of course, there was Coleman’s son Denardo, the only player<br />

other than Ornette himself to appear on every Prime Time record,<br />

as immersed in his father’s ways of thinking as one could be.<br />

These musicians were more than just sympathetic collaborators;<br />

they were disciples in the school of harmolodics. And on Of<br />

Human Feelings, that change is easy to recognize: All six players<br />

are on their own, playing in differing keys and rhythmic<br />

cadences, but it’s also obvious how deeply they’re listening to one<br />

another. Listen to the guitar interplay between Bern Nix (the<br />

ultra-clean tone in the left channel) and Charles Ellerbee (the<br />

more distorted one panned to the right) on a track like “Him and<br />

Her.” They’re playing off of each other, ducking in<br />

and out of each other’s lines, filling in gaps, but they never lose<br />

their respective individual characters. One can focus on any<br />

combination of players and observe astounding repartee. It’s<br />

ironic, perhaps, given how haphazard the music might sound on<br />

first listen, but Of Human Feelings exists at the apex of musical<br />

connectedness.<br />

Returning finally to the question of album titles, we should<br />

consider Of Human Feelings itself <strong>—</strong> it doesn’t share the temporal<br />

theme of those earlier titles, but it may be even more elucidating<br />

of Coleman’s concerns. Plenty of art claims to abide by a similar<br />

expressive principle, but few works actually apply that humanist<br />

impulse to something radical, stripping away all conceivable<br />

barriers in pursuit of a pure, liberated expression. If anyone can<br />

be said to have made a music of human feelings, it’s Ornette<br />

Coleman. <strong>—</strong> BRENDAN NAGLE<br />

17

FILM REVIEWS<br />

SCREAM VI<br />

Tyler Gillett, Matt Bettinelli-Olpin<br />

What started more than two decades ago as a completely<br />

unexpected shot in the arm for a mostly dead subgenre has<br />

steadily declined into being exactly the thing that its initial<br />

mission statement railed against. Scream VI, the latest in what’s<br />

becoming horror’s most insufferable series, is almost<br />

catastrophically tired, offering not a single novel or surprising<br />

moment. Instead, it dives deeper into boring self-mythologizing,<br />

ludicrous sub-TV procedural plotting, and a fully irritating<br />

continued insistence that this has anything to do with movies or<br />

meta text, all of it served up by characters nobody could possibly<br />

be bothered to care about. Without a doubt, it’s the laziest entry<br />

yet.<br />

Shifting locations at last from Woodsboro, California <strong>—</strong> we’re now<br />

in Manhattan <strong>—</strong> Scream VI rejoins the last film’s survivors: Mindy<br />

(Jasmin Savoy Brown) and her brother Chad (Mason Gooding) <strong>—</strong><br />

both, annoyingly, related to Jamie Kennedy’s “legacy” character,<br />

more on that crap later <strong>—</strong> and heroines Sam and Tara Carpenter<br />

(Melissa Barrera and Jenna Ortega, respectively), all of whom<br />

have left their murder-besieged hometown for New York City to<br />

attend college together. All seem mostly OK except for Sam, who<br />

harbors a nasty case of PTSD due to both the events of Scream<br />

(2022) and the knowledge that she’s the daughter of Scream<br />

(1996) killer Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich, once again returning for a<br />

CGI-de-aged cameo). Welp, too bad, because Ghostface has<br />

popped up yet again, claiming that he’s going to punish Sam and<br />

Tara for… apparently not getting killed last time. How dare they?<br />

This time the prospective killer or killers are obsessed with past<br />

Ghostfaces, even going so far as building a massive shrine to the<br />

previous crimes in an abandoned movie theater, a cute idea that<br />

falls apart under the slightest scrutiny, which wouldn’t be a<br />

problem except that the film is so boring you’ve got nothing else<br />

to think about except the stuff that doesn’t make sense (why do<br />

the authorities never once examine this place forensically and<br />

17 18

FILM REVIEWS<br />

why do the characters have the keys to it?). Meanwhile, Scream<br />

4’s Kirby (Hayden Panetierre) is also back as an FBI agent, and of<br />

course Gale Weathers (Courtney Cox) needs a paycheck, too,<br />

prompting this movie’s movie geek character to embark on a<br />

truly embarrassing diatribe about the vulnerability of “legacy”<br />

characters. Why do the Scream movies always have to have their<br />

characters talk about movies like they’re in an 8th grade<br />

after-school film club?<br />

Outside of some briefly effective bits that you could count on one<br />

hand, there’s nothing exciting about any of this. The Scream<br />

structure has become so ossified and the films’ direction so<br />

generic that the entire enterprise is fully diluted. All that’s left is<br />

for the audience to wait until the end when the villain's or villains'<br />

identity is revealed. This one isn’t quite as easy to call as the last<br />

one, but anybody paying the least bit of attention will probably<br />

still figure out most of it. Meanwhile, Wes Craven’s literate but<br />

prankster-ish personality is once again sorely missed; Scream 3<br />

wasn’t a very good movie either, but there’s not a single idea in<br />

this movie as good as the scene in that one where heroine Sid is<br />

chased through a film set of the childhood home where she’d<br />

previously survived multiple murder attempts. As Mindy the<br />

movie geek says at one point here: “Fuck this franchise.” <strong>—</strong><br />

MATT LYNCH<br />

DIRECTOR: Tyler Gillett & Matt Bettinelli-Olpin; CAST: Melissa<br />

Barrera, Jenna Ortega, Courtney Cox; DISTRIBUTOR: Paramount<br />

Pictures; RELEASE DATE: March <strong>10</strong>; RUNTIME: 2 hr., 3 min.<br />

65<br />

Scott Beck, Bryan Woods<br />

One of the most accomplished actors of his generation, equally<br />

adept at conveying volcanic rage and soft-spoken humility, Adam<br />

Driver’s greatest gift arguably is that he has fantastic taste in<br />

material. Cribbing from Tom Cruise’s early career playbook, Driver<br />

has prioritized appearing in original screenplays and working<br />

with the era’s preeminent filmmakers over showing up in<br />

franchises and extended cinematic universes (even his time<br />

spent in a galaxy far, far away came with the promise of being<br />

directed by J.J. Abrams, which seemed like a good idea back<br />

when the project was first announced). Driver’s still in his thirties<br />

and has already worked with the likes of Scorsese, Spielberg, the<br />

Coens, Ridley Scott, Jarmusch, Carax, Spike Lee, Soderbergh, and<br />

Baumbach (and he still has Michael Mann’s Ferrari, presumably<br />

due later this year). All of which is to say, when Driver appears in<br />

a dud like 65, it stands out all the more. It’s not simply that he’s<br />

better than the film, it’s that he must realize it, and so one finds<br />

themselves leaning forward, trying to make sense of what even<br />

attracted the actor to the role in the first place. Perhaps he<br />

wanted to make something his young child could appreciate, or<br />

maybe he secretly longed to film a dinosaur movie, or (most<br />

likely) it simply paid well and coincided with a gap in his<br />

schedule. Whatever the reason, the resulting film doesn’t serve<br />

him especially well, nor he it.<br />

Established in an opening title card that the film is set millions of<br />

years in the past on the other side of the universe <strong>—</strong> one could<br />

imagine this playing as a Planet of the Apes-like revelation for the<br />

audience, spoiled by overeagerness <strong>—</strong> where stoic spaceman and<br />

#GirlDad Mills (Driver) has made the difficult decision to embark<br />

on a two-year-long mission, ferrying passengers across the<br />

cosmos in order to make enough money for his daughter’s<br />

life-saving medical treatment. Serving as pilot and sole<br />

passenger not tucked away in cryostasis, Mills is jarred awake<br />

mid-mission as his ship flies into an uncharted asteroid field.<br />

With his ship suffering catastrophic damage, jettisoning cryo<br />

pods all the way down, Mills makes an emergency crash landing<br />

on an unsettled planet inhabited by hostile “alien” creatures that<br />

the viewer will recognize as dinosaurs (again, this is something<br />

that might have been fun to discover while watching the film<br />

instead of being front and center in its marketing campaign).<br />

With his ship irreparably crippled, all his passengers dead, and<br />

seemingly no hope for rescue, Mills steps outside with the<br />

intention of blowing his brains out, only to be halted by memories<br />

of his adorable daughter and the sight of one of the stray cryo<br />

pods with a passenger still alive inside of it. Upon rescuing young<br />

Koa (Ariana Greenblatt), a child around his daughter’s age who<br />

rather inconveniently doesn’t speak English, Mills rediscovers his<br />

sense of purpose and sets out with his young ward to find the<br />

escape craft attached to the other half of his ship all while<br />

avoiding T-Rexes, quicksand, killer parasites, and other<br />

Cretaceous-era dangers.<br />

Despite its high-concept premise, 65 is fundamentally modest in<br />

its ambitions. Running a brisk 93 minutes (one of the best<br />

19

FILM REVIEWS<br />

arguments in its favor), there isn’t much fat on the film <strong>—</strong> we’re<br />

already well into the story by the time we get to its opening title.<br />

We’re long past the novelty of seeing prehistoric creatures<br />

depicted on screen, and the film seems to recognize as much,<br />

treating packs of Compsognathuses and other “smaller”<br />

dinosaurs practically like house cats jumping out at the screen,<br />

simply to goose the viewer before working its way up to the boss<br />

dinosaurs. With its “modern” adventurer and small child in tow,<br />

running and gunning at dinosaurs, the film calls to mind a less<br />

campy version of the old Land of the Lost TV series, something<br />

which, on the face of it, sounds diverting enough. But Driver’s all<br />

wrong for material this flimsy, radiating self-seriousness and<br />

steely intelligence when what the film demands is someone who<br />

can appear nonchalant popping his shoulder back into place just<br />

in time to snatch his laser rifle and blast advancing giant lizards.<br />

There’s an under-served strain of trauma and depression<br />

ribboned throughout the film <strong>—</strong> between the crash, the nod to<br />

suicide, and subsequent rededication to survival, at times 65<br />

resembles a jankier version of Joe Carnahan’s The Grey, a<br />

comparison which feels less and less like a coincidence as it<br />

progresses <strong>—</strong> which may have been what appealed to Driver<br />

about the script, but here it’s so cut to the bone it would have<br />

benefited from being excised altogether.<br />

The film was directed by the team of Scott Beck and Bryan<br />

Woods, who, having written A Quiet Place, know of melding family<br />

drama with a creature feature. But what’s missing is the sense of<br />

showmanship, an emphasis on visual storytelling, or even the<br />

sort of drawn-out setpieces favored by their A Quiet Place<br />

director, John Krasinski. The film’s in such a hurry to get to the<br />

next “thrilling” moment or to “up the stakes” (it introduces a<br />

ticking clock element around the halfway point that, if nothing<br />

else, explains why 20th-century excavators never stumbled onto<br />

all this cool, intergalactic technology) that it hurtles past any of<br />

the theoretical grandeur of the premise. It’s not easy to make<br />

spaceman vs. dinosaurs feel commonplace, but somehow 65<br />

pulls it off. Not helping matters is how derivative this all is,<br />

shamelessly reappropriating motifs, shots, and entire sequences<br />

from the likes of Interstellar and the first two Jurassic Park films.<br />

In the absence of anything truly innovative or even particularly<br />

20

FILM REVIEWS<br />

exciting, any hope of the film succeeding lands on its leading<br />

man’s shoulders. But without any other adults to interact with,<br />

the film plays to none of Driver’s strengths, leaving the actor little<br />

to do but react to CGI beasties, fire futuristic weapons, and<br />

over-emote in order to convey basic information to a confused<br />

moppet. Adam, you’re better than this; leave this sort of thing to<br />

one of the Chrises. <strong>—</strong> ANDREW DIGNAN<br />

DIRECTOR: Scott Beck, Bryan Woods; CAST: Adam Driver, Ariana<br />

Greenblatt, Chloe Coleman; DISTRIBUTOR: Sony Pictures;<br />

RELEASE DATE: March <strong>10</strong>; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 33 min.<br />

CHAMPIONS<br />

Bobby Farrelly<br />

Filmmaking duo and brothers Peter and Bobby Farrelly have<br />

received more than their fair share of vitriol over the years for<br />

their particular brand of humor, one where no gag was ever<br />

deemed too stomach-churning or offensive if it meant a hearty<br />

laugh from its intended audience. Unsurprisingly, this ushered in<br />

an era of studio comedies that wore their lack of political<br />

correctness as a shiny badge of honor, one that could barely<br />

conceal the hatred that bubbled underneath, even as the<br />

Farrellys themselves rarely engaged in mean-spirited hijinks.<br />

Their hearts were always far too big for that, with the duo going<br />

out of their way to cast persons with physical and developmental<br />

disabilities in both bit parts and featured roles, steadfastly<br />

refusing to ever make them the butt of the joke. Even the<br />

fat-shaming of Shallow Hal ultimately dovetailed with a message<br />

of acceptance above all else, and perhaps that’s why the Farrellys<br />

have been maligned for so long <strong>—</strong> two guys who both<br />

wanted their cum-covered cake and to eat it, too.<br />

It has been six years since the Brothers Farrelly parted ways.<br />

Peter went the Oscar bait route with Best Picture winner Green<br />

Book <strong>—</strong> a film far more offensive than anything in the duo’s<br />

arsenal of juvenalia <strong>—</strong> and Bobby’s finally having his day in the<br />

sun with new inspirational sports comedy Champions, in which a<br />

ragtag group of young adults compete in a regional basketball<br />

tournament for a spot in the Special Olympics. To find Bobby<br />

working in this particular narrative lane isn’t the least bit<br />

shocking, bringing to the foreground he always sought to, well,<br />

champion in previous features. What’s a tad more surprising is<br />

that he had nothing to do with the script itself, which comes<br />

courtesy of first-timer Mark Rizzo, who here adapts the 2018<br />

Spanish-language film of the same name. (And to be brutally<br />

honest, both movies should be crediting the creators of Disney’s<br />

beloved 1992 hit The Mighty Ducks, which Champions copies<br />

beat-for-beat when it comes to plot). Tell me if you’ve heard this<br />

one before: Woody Harrelson stars as Marcus, an arrogant<br />

athletic coach who, after receiving a DUI, is court-ordered to<br />

fulfill his community service by coaching a down-on-their-luck<br />

team in need of some guidance. At first appalled by the position<br />

<strong>—</strong> a seeming demotion to the NBA-aspiring Marcus if ever there<br />

was one <strong>—</strong> the selfish bastard soon befriends the eccentric<br />

members of his team and discovers the compassion inside<br />

himself that was long ago buried, falling for one of the player’s<br />

parental units <strong>—</strong> oops, this time it’s a sister, Alex (Kaitlin Olson) <strong>—</strong><br />

in the process. Can he be redeemed by his young charges? Or will<br />

the unrelenting pull of a big-time job in prove his undoing?<br />

So no, Champions doesn’t go anywhere the viewer hasn’t already<br />

traveled a thousand times before, but the same can be said for<br />

most films in this particular genre. It all comes down to the<br />

details, those small wrinkles that can thankfully distract from the<br />

well-worn bigger picture, and it helps immensely that Farrelly<br />

chose to cast actual persons with disabilities as the team’s core<br />

players, lending an authenticity that is sorely lacking from other<br />

films of this ilk. Much like 2008’s similarly themed comedy The<br />

Ringer, Champions paints its protagonists as both no-nonsense<br />

and the most capable people in the room at any given moment,<br />

their zeal and forthrightness a refreshing counterpoint to the<br />

self-absorbed jerk leading the team. It’s of course an obvious<br />

juxtaposition to operate on, but that doesn’t make it any less<br />

effective in execution.<br />

21

FILM REVIEWS<br />

Unfortunately, unlike The Ringer, which had edge to spare,<br />

Champions is as square as they come, its message of acceptance<br />

and tolerance welcomingly earnest, but packaged and delivered<br />

in the blandest way possible. The film also feels like a relic from<br />

another era, specifically the 1990s, with the movie at one point<br />

stopping dead in its tracks for literally five minutes so that<br />

co-star Cheech Marin can explain how persons with disabilities<br />

can lead rich and fulfilling lives <strong>—</strong> it’s a real yikes moment in an<br />

otherwise well-meaning project. And then we have the<br />

soundtrack, which is filled with such modern-day hits as<br />

Chumbawamba’s “Tubthumping,” which is featured… twice. In<br />

fact, if it weren’t for the constant sex jokes, this would all work<br />

perfectly for the under-12 crowd, (though the film is being<br />

released into 2023 America, so there’s really no age limit for who<br />

needs lessons in decency). And therein lies the rub when it<br />

comes to Champions: the movie is so well-intentioned that<br />

criticizing it feels like kicking a puppy, but it also rarely rises<br />