You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

Practices, Policies and Challenges<br />

Edited by<br />

Huib Schippers, Wei-Ya Lin and Boyu Zhang

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

Practices, Policies and Challenges

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

Practices, Policies and Challenges<br />

Edited by<br />

Huib Schippers, Wei-Ya Lin and Boyu Zhang<br />

Copyeditor<br />

Ching-Wah Lam<br />

Central Conservatory of Music Press

Huib Schippers, Wei-Ya Lin and Boyu Zhang (eds.)<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. Practices, Policies and Challenges<br />

Wien: HOLLITZER Verlag, 2024<br />

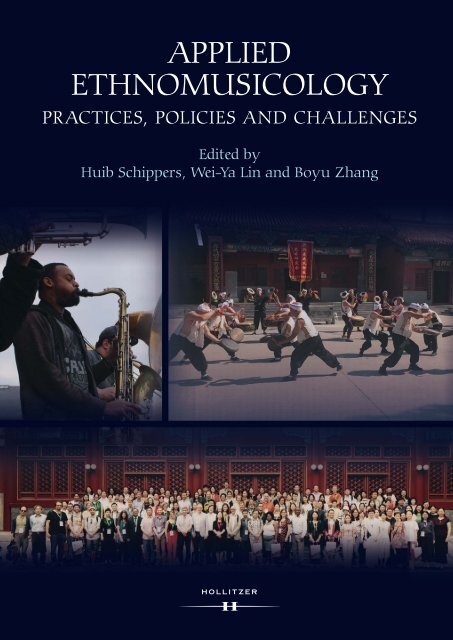

Cover Images<br />

Front cover (counterclockwise): Crush funk celebrating the opening of the community-focused<br />

Smithsonian Year of Music on Jan 1st, 2019. Photo: Huib Schippers; Participants of The Joint<br />

Symposium of the ICTM Study Groups on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> (6th) and Music, Education<br />

and Social Inclusion (2nd) in Beijing, 2018. Photo permission: CCOM; Weifeng Luogu, percussion<br />

ensemble locally popular in Shanxi. Photo: Boyu Zhang; Back cover: Community dance in<br />

Middletown, Connecticut, 2006. Photo: Boyu Zhang; 5. Traditional healers with Igubu, Hobeni,<br />

South Africa, 2008. Photo: Bernhard Bleibinger.<br />

All rights reserved<br />

© Central Conservatory of Music Press, Beijing and Hollitzer Verlag, Wien<br />

Printed and bound in the EU<br />

ISBN 978-3-99094-214-7

Contents<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

VII<br />

Preface: Study Groups, Honeybees, and Dialogues in <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 1<br />

Anthony Seeger<br />

Introduction: The Vibrant and Diverse Practices of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 7<br />

Huib Schippers<br />

Part One:<br />

General Reflections on the Field<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in China and Beyond: Dialogues and Reflections 15<br />

Boyu Zhang<br />

Outreach, Inreach, Transreach? - Defining Types of Musical Community<br />

Engagement 30<br />

Bernhard Bleibinger<br />

Let’s Not Forget the Larger Context: Short-term <strong>Applied</strong> Projects and<br />

Long-term Sustainability 47<br />

Anthony Seeger<br />

Part Two:<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and Intangible Cultural Heritage<br />

Ways of Engaging with Traditional Music Performances by Chinese<br />

Ethnomusicologists: A Personal Perspective 63<br />

Xiao Mei & Yukun Wei

Uyas Kmeki of the Seediq: A Case Study on the Efforts toward Cultural<br />

Sustainability in Taiwan 76<br />

Yuh-Fen Tseng<br />

Practice and Experiment: China’s National Cultural Ecosystem Conservation<br />

Areas as a New Approach to Intangible Cultural Heritage 94<br />

Gao Shu<br />

Incorporating Intangible Cultural Heritage in a Local Conservatory:<br />

The Case of Dongbei Dagu, a Narrative Art from Northeastern China 109<br />

Zhilian Feng<br />

Part Three:<br />

Applying <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in Various Settings<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in Museum Exhibitions: Critical Reflections on Sound<br />

Narratives as a Method for Knowledge Transfer 123<br />

Matthias Lewy<br />

“Music Without Borders”: Austria as a Case Study in Conducting Intercultural Music<br />

Education Through <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 135<br />

Wei-Ya Lin<br />

Performing Cultural (Un-) Sustainability: Rationale and Impact of an<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> Theatre Workshop in a West-African Graduate Programme 153<br />

Pepetual Mforbe Chiangong & Nepomuk Riva<br />

Rama and the Worm: A Performance-Based Approach to<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 167<br />

Dan Bendrups, Robert G. H. Burns, & Henry Johnson<br />

“Quilombo, Favela, Rua”: Sarau Divergente in the Fight against<br />

Black Genocide in Rio de Janeiro 177<br />

Grupo de Pesquisa em Etnomusicologia Dona Ivone Lara (GPEDIL)<br />

Note: Other than Xiao Mei and Gao Shu, all Chinese names are presented with family names<br />

coming last.

Acknowledgements<br />

This publication is the outcome of the 6 th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group<br />

on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in combination with the Second Symposium of the<br />

ICTM Study Group on Music Education and Social Inclusion, which took place<br />

in Beijing in 2018. The event brought together applied ethnomusicologists (and<br />

educators) from all over the world. As the current Chair of the ICTM Study Group<br />

on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, I would like to acknowledge my two predecessors,<br />

Svanibor Pettan and Klisala Harrison, who have both done so much for the Study<br />

Group and <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> at large over the past two decades. I would<br />

also like to express my gratitude to the Central Conservatory of Music for hosting<br />

the meeting, and particularly to Boyu Zhang and his team for organizing the event,<br />

as well as my colleagues in the Study Group, Executive, and Programme Committee<br />

(particularly our wonderful secretary Wei-Ya Lin). I would like to especially<br />

thank the three interpreters Qian Mu, Xinjie Chen and Shuo Yang, who tirelessly<br />

translated every session in the conference, and thus played a crucial role in the realtime,<br />

vivid exchange between scholars who are usually not able to exchange ideas<br />

through the Mandarin-English language divide. We hope that his volume brings<br />

to life some of the experience of how their work opened new worlds of ideas and<br />

practice for all participants.<br />

VII

Preface<br />

Study Groups, Honeybees,<br />

and Dialogues in <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

Anthony Seeger<br />

Scholars who attend conferences and study group meetings are a little like<br />

honeybees. Bees sip sweet nectar from flowers and carry pollen to other flowers<br />

and then return to the hive to make honey and raise more bees. Before COVID I<br />

attended many conferences every year. I would enjoy the company of old friends<br />

and newly-met colleagues, the food, and the excitement of hearing ideas I had<br />

never thought about before. I often attended concerts of music I had never seen<br />

performed. The pleasure of these encounters was the sweet nectar that drew me,<br />

like a bee, to the conferences. After they ended I would carry some of the new ideas<br />

with me to the next conference, where I would leave some ideas and pick up a few<br />

new ones. This is how a bee pollinates flowers, and how many scholars exchange<br />

ideas. Most of the participants in this study group were scholar-honeybees as well.<br />

Even the translators, who were also scholars, helped to refine our understanding of<br />

the concepts. Everyone brought original ideas and carried new ideas away to other<br />

places. Even if you were not at that study group meeting you can be a honeybee by<br />

reading this book. You bring to your reading your ideas and experiences and you<br />

may find things here that you will carry with you to your professional activities,<br />

your teaching, or the communities in which you live.<br />

I am writing this more than a year after COVID19 ended most in-person<br />

professional meetings. Recalling our conference in July 2018 brings back vivid<br />

and nostalgic memories of the intense social and intellectual interactions that<br />

ended abruptly in 2020. Online conferences may be useful for communicating<br />

ideas, but they are very different from meetings. Participants at study group<br />

meetings communicate in many different ways and can form collaborative<br />

academic relationship that may endure a lifetime. This was certainly true of<br />

the 2018 meeting in Beijing of the combined ICTM study groups “<strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” and “Music, Education, and Social Inclusion,” where a brilliant<br />

assemblage of international scholars, including many from the People’s Republic<br />

of China, presented and discussed the definitions of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and<br />

how <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> can be applied, including a variety of approaches to the

2 Preface<br />

safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). As so often, meals were an<br />

essential part of the sharing of ideas. We filed into the buffet for our lunches and<br />

asked our neighbors about what to put on our plates. We squeezed into booths or<br />

sat at tables with someone we knew and other people we had not yet met. As we ate<br />

we talked with each other about the papers we had heard. We smiled and waved at<br />

people at other tables. When a lack of a shared language made conversation difficult,<br />

a smile and a gesture communicated the pleasure of being at the same exciting event,<br />

or appreciation of the other’s presentation. Tea and coffee in abundance kept us<br />

awake, for the days were long and there were tours, concerts, and other events where<br />

we met one another in different circumstances and got to know different things<br />

about each other.<br />

This collection of essays may be less exciting than that conference. Among<br />

other things, you have to supply your own food and drink. And there is often<br />

nobody around with whom to talk about the chapter you just read. But, in<br />

compensation, every one of these chapters has been improved by its author’s<br />

participation in the study group meeting. And the written word is often easier to<br />

understand than spoken language because you can re-read a sentence, look up a<br />

word, or underline it for future reference. Later you may take the ideas and the name<br />

of the author to another conference, a classroom, or to your research projects and<br />

talk about them, refine them, and pass them along.<br />

Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and a thoughtful<br />

scholar and inventor, wrote in 1813 that we can give ideas to each other without<br />

losing anything ourselves. Although intellectual property (IP) laws have limited the<br />

process he described, it certainly applies to most scholarly conferences. You will also<br />

see that he considered the spread of ideas to have a practical, or applied, purpose:<br />

“He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening<br />

mine; as he who lights his taper [candle] at mine, receives light without darkening<br />

mine. That ideas should freely spread from one to another all over the globe, for<br />

the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition,<br />

seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she<br />

made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density<br />

at any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical<br />

being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation” (Thomas Jefferson<br />

letter from 1813, quoted in Hyde 2010: 91).<br />

I prefer my metaphor of the honeybee to Jefferson’s candle. A honeybee collects<br />

nectar without diminishing the beauty of flowers and makes honey while spreading<br />

the pollen that enables them to propagate. Most <strong>Applied</strong> Ethnomusicologists are<br />

very busy, like bees. And, like bees, when we learn new ideas we aren’t taking<br />

anything away from their originators. We owe them recognition, however, and a<br />

place to present their own ideas, as in this book. Each chapter is like the honey from<br />

the nectar of many sources.

Study Groups, Honeybees, and Dialogues in <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 3<br />

What is <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>?<br />

This is a book about <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> across the globe. It may be useful<br />

to briefly look at what these words mean. The word “<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” is not<br />

universally accepted. Some people confuse it with “ethnic” musicology and others<br />

see in it a legacy of colonialism. It is an approach to music that considers the sounds<br />

of music and also their meanings and the way humans use them in their lives. The<br />

word <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is useful because so many musicologies are narrowly focused.<br />

Ethnomusicologists have argued about the word a lot, especially in the early years<br />

of the Society for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. A few ethnomusicologists think that when<br />

musicology shares all the essential elements of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, then the word<br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> will no longer be needed. Some people think this has occurred in<br />

the 21 st century; others feel the word and specific approaches of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

to music are still distinctive and necessary. For me, the word <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is less<br />

important than Ehnomusicology’s approach to music and social life.<br />

The first feature of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is that it is an approach to all music and<br />

ways of conceptualizing it. Many nations and communities within nations have their<br />

own ways of thinking about and talking or writing about their music. These are<br />

shaped by their ideas about sounds, time, aesthetics, space, humans, animals, deities,<br />

and other denizens of the universe. For example, if a community thinks all music<br />

is created by gods or spirits, its musicology might not include the study of the lives<br />

of human composers (because there are not thought to be any). This is true of some<br />

Indigenous peoples in Brazil (A. Seeger 2004). Euro/American musicology, on the<br />

other hand, does not consider animals or spirits to be important. Instead, it includes<br />

extensive studies of the lives of human composers because they are thought to be<br />

the origin of music. In another example, if a community thinks music should sound<br />

like what is described in a sacred text, there may be other sounds that an outsider<br />

would call “music” that are not considered by that community to be music at all<br />

because they don’t conform to the sacred text. In short, different things may be<br />

called music in different places, and the musicology in different places may reflect<br />

those ideas. Most musicologies have focused largely on particular aspects of their<br />

own community’s music. But people who encounter different sounds and ways of<br />

making and talking about them have a choice. They can say “what doesn’t sound like<br />

my music isn’t music; it’s just non-musical noise,” and “what they are saying about<br />

music isn’t musicology, it’s ideology, mythology, or folklore.” Alternatively, they<br />

can change their way of thinking and accept all definitions of music and all ways of<br />

talking or writing about it as “musicology.” Those choosing the second options are<br />

often called ethnomusicologists because their musicology isn’t limited to their own<br />

community’s music and musicology. Instead, ethnomusicologists seek to understand<br />

all music and all musicologies.<br />

There is a second feature of the word <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. Most ethnomusicologists<br />

study not just the sounds of music, but also the meanings of those sounds to the<br />

people who perform and listen to them and the social processes of which their music

4 Preface<br />

is a part. It is a combination of the words “ethnology” and “musicology” and one<br />

of its central methods is extensive ethnographic research. Thus, <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

is the study of both the musical aspects of life and the social aspects of musical<br />

performances. It includes the study of the meaning, production, and sound<br />

structures and histories of local “traditional” music (however defined) and also of<br />

transnational media-driven popular music. It includes the study of the music of<br />

worship, but also of advertising. It includes the music of minority and majority<br />

peoples of different ages, genders, and social and political groups. And just as there<br />

are local musicologies, different variants of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> have developed around<br />

the world, taking inspiration from both local and outside ideas about how to study<br />

music in its social contexts.<br />

What is <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>?<br />

The word “applied” is more or less clear to Europeans and North Americans who<br />

work in colleges and universities. It refers to using the tools of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> to<br />

work outside of educational institutions. The reason the word “applied” is used to<br />

describe only some kinds of ethnomusicological work in both North America and<br />

Europe is that university life and investigation are valued in themselves and do not<br />

need to be directly related to immediately practical objectives. For example, a debate<br />

on the best way to transcribe musical sounds—something that occupied the Society<br />

for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> for some years in the 1950s and 1960s—does not necessarily<br />

need to have an impact on life outside the university. The impact of the debate is on<br />

ideas about sounds and the best methods for analyzing them, which are academic<br />

pursuits. <strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists, in contrast, want to take the implications and<br />

methods of scholarship and apply them to non-academic processes, which include<br />

ecological and social crises. Using the example above, this might include using<br />

the best transcription method available for creating transcriptions for dispersed<br />

communities to revive partially forgotten musical performances.<br />

This meaning of “<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” may not be clear to scholars<br />

in other parts of the world. One of the sessions at the study group focused on the<br />

definition of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. Svanibor Pettan, one of the founders of<br />

the ICTM Study Group for <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, stressed that the essence of<br />

the concept is in a scholar’s social responsibility and the decision to use scholarly<br />

understanding of music to help solve urgent social problems within and outside<br />

of educational institutions. In the US, the definition of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

does not highlight social responsibility. <strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists may work<br />

with immigrants, but they may also work for marketing companies, government<br />

programs, radio stations, museums, recording companies, and other businesses.<br />

Hui Yu and Xiao Mei observed that universities in China are supposed to serve the<br />

broader interests of the country, and thus all of their academic work is applied, and<br />

all their <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is applied. Ever since I was a child I have thought that<br />

knowledge should be used for the benefit of people, and thus I have thought that my

Study Groups, Honeybees, and Dialogues in <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 5<br />

scholarship should be not only interesting to me and some of my colleagues but also<br />

useful in practical ways as well. Many of my colleagues share this belief.<br />

But <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> doesn’t only benefit the non-academic community.<br />

It can also benefit the academic study and instruction of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>.<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists can help their university colleagues to better understand<br />

aspects of music of which they are unaware and, thus, change their discipline.<br />

Charles Seeger (1886–1979) considered the importance of applied activities for<br />

musicology in a 1939 conference paper. He suggested that an important role<br />

for applied musicology (the word “<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” was not yet in common<br />

use) would be to improve academic musicology. He wrote: “Without an applied<br />

musicology the pure study [of music] must of necessity know less well where it<br />

stands, where it is going, where its weak links are, what motivation lies behind<br />

it, and what ends it serves” (C. Seeger 1939:17). In other words, music scholars<br />

working outside of academic contexts can contribute to the very discipline they<br />

trained in. Many people who are not musicologists also work with music in<br />

communities outside of universities. But <strong>Applied</strong> Ethnomusicologists who work<br />

outside universities are frequently trying to improve the field of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

itself. Some subjects are better understood through action-oriented research than<br />

through academic contemplation. <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> has changed and taken on a<br />

more applied ethnomusicological stance during the last decade, as evidenced in<br />

Hemetek, Köbl, and Sağlam (editors) <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Matters, Influencing Social and<br />

Political Realities (2018) and Diamond and Castelo-Branco (editors) two-volume<br />

Transforming <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> (2021), among others.<br />

In considering the definitions of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>,<br />

it is worth remembering that the ICTM is not called the International<br />

Council for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is an academic discipline of global<br />

scope with practical applications. The ICTM is a “scholarly organization which<br />

aims to further the study, practice, documentation, preservation, and dissemination<br />

of traditional music and dance of all countries” (ICTM 2021). Central elements of<br />

its mission are applied: furthering the practice and preservation of music and dance<br />

traditions. A particular approach or discipline through which to achieve this isn’t<br />

specified. People with many different kinds of training and expertise can contribute<br />

to this mission. They do not need to call themselves ethnomusicologists. Academic<br />

disciplines change their names, their subject matter, and may even cease to exist over<br />

time. Music and dance have been part of human activity for millennia and will likely<br />

be performed long after the disciplines studying them have become unrecognizable.<br />

In conclusion, I return to my metaphor of conferences, flowers, and honeybees.<br />

A flower has to bloom and produce pollen before a honeybee can sip its nectar<br />

and carry grains of pollen on to other flowers. Similarly, a conference has to be<br />

conceived, organized, and successfully managed for its participants to attend,<br />

participate, exchange ideas, and depart. Participants need to have hotel rooms, food,<br />

drink, opportunities to enjoy the local setting, and arrangements for returning

6 Preface<br />

home. And the academic program requires a lot of thought as well. The theme of<br />

the conference has to be enticing. The panels must be organized in creative ways<br />

that bring different people and ideas together before interested audiences. Programs,<br />

books of abstracts, and a list of participants help those involved remember what they<br />

heard after they get home and give them a way to contact presenters should they<br />

wish to. When a conference goes so smoothly that the participants don’t even realize<br />

what a huge task it is, the result is very enjoyable, exciting, and productive. The<br />

meeting of the ICTM Study Group for <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in Beijing was so<br />

well organized that it was like a perfect flower, and the scholar-bees that attended<br />

had a lot to think about and to do. Everyone involved in organizing it deserve the<br />

gratitude of those who participated. Books like this one require determined and<br />

skillful editors, a lot of time, and difficult decisions. The authors of the chapters<br />

assembled in this book all benefitted and contributed to the study group meeting’s<br />

success. This collection of essays is some of the honey produced from it. Read the<br />

contributions, take ideas and approaches you find interesting, use them, and pass<br />

them on to others.<br />

References:<br />

Diamond, B., & Castelo-Branc, S. (2021). Transforming <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. 2 volumes. Oxford: Oxford<br />

University Press.<br />

Hemetek, U., Kölbl, M., & Sağlam, H. (Eds). (2019). <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Matters: Influencing Social and<br />

Political Realities. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co.<br />

Hyde, L. (2010). Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.<br />

ICTM. (2021). ICTM Webpage, url: https://ictmusic.org/group/applied-ethnomusicology (Accessed:<br />

18 April 2021).<br />

Schippers, H., & Seeger, A. (Eds.). (2022). Music, Community, and Sustainability. New York: Oxford:<br />

Oxford University Press.<br />

Seeger, A.. (2004). Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People. Urbana: University of<br />

Illinois Press. (Translations in Chinese and Portuguese.)<br />

Seeger, C. (1939). Music as A Factor in Cultural Strategy in America. Bulletin of the American<br />

Musicological Society 1939 (3): 17–18.<br />

Anthony Seeger is an Anthropologist, Ethnomusicologist, and Professor Emeritus of the University of Califonia Los<br />

Angeles

Introduction<br />

The Vibrant and Diverse Practices of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

Huib Schippers<br />

Many “first generation applied ethnomusicologists” recall doing things for the<br />

musicians and communities they work with going back many decades, such as<br />

organizing concerts, tours or recordings with musicians. My own adventures in this<br />

realm can serve as an example: In the late 1970s, I served on the board of Tritantri,<br />

my sitar teacher’s music school. In the early 1980s, I founded Musiques du Monde, a<br />

small world music record shop located on one of the canals of Amsterdam. A few<br />

years later, with a few fellow music critics, I launched the magazine Wereldmuziek,<br />

the first Dutch-language public-facing periodical on what was then the exciting new<br />

phenomenon of “world music” (a term which has lost some of its shine since then).<br />

In the 1990s, I helped develop a dozen publicly funded, community-oriented world<br />

music schools across the Netherlands. Later came laying the foundations and finding<br />

funding for the Codarts World Music & Dance Centre in Rotterdam, which opened<br />

in 2006, bringing together degree courses, research, community outreach, music in<br />

schools and events celebrating musical diversity, all under a single roof. Next was<br />

a series of festivals on intercultural meetings, Encounters (2005–2013), while I was<br />

professoring and building an innovative music research centre at Griffith University<br />

in Australia as my day job. And then there was the record label Smithsonian<br />

Folkways in Washington DC (2016–2020): helping revitalise an iconic institution<br />

that gives voice to underrepresented people and sounds to an annual audience of<br />

hundreds of millions (Schippers 2021). Many colleagues, including some of the<br />

contributors to this volume, have similar stories, with many variations in focus and<br />

scale.<br />

Then, in the course of the 1990s and early 2000s, we found out that the work<br />

that had grown organically from us seeing needs and opportunities outside the realm<br />

of our strictly scholarly duties suddenly came to be called “applied.” I think that<br />

naming was less meaningless than it may sound. Drawing specific attention to the<br />

work in this sphere (I’ll come back to how narrow or wide that sphere may be) has<br />

enabled us to create theoretical, practical, organisational, philosophical, and ethical<br />

frameworks which help us understand, develop and guide this type of work further,<br />

as it differs significantly from the “hands-off ” approach that largely dominated

8 Introduction<br />

the first 100 years of our discipline (for those of us who choose Adler’s 1885 essay<br />

as the start date). As this volume demonstrates, it provides the opportunity to<br />

recalibrate existing practices, carefully design new ones, and celebrate the continuing<br />

spontaneous outbursts of care for communities that may not even have been<br />

designed as “applied ethnomusicology,” but can fruitfully be described as such after<br />

the fact.<br />

In terms of existing practices, perhaps the most striking instances come from<br />

China, where—as some of our contributors argue convincingly—the brief of<br />

ethnomusicologists has always been applied in various ways. Boyu Zhang’s opening<br />

chapter in this volume refers back as far as Confucius, but gets very concrete from<br />

the Cultural Revolution. Since then, ethnomusicologists in China have been<br />

working for a variety of clearly defined non-academic purposes: from supporting<br />

composers in their creative work by providing insights into the structures of folk<br />

music, to playing a key role in the country’s unparalleled efforts towards greater<br />

cultural diversity and sustainability since the beginning of this century, always as<br />

“part of the construction of the Chinese nation-state,” as Xiao Mei puts it. Using a<br />

plenary panel at the 2018 meeting as a springboard, Boyu observes how definitions<br />

and approaches seem to differ greatly between SEM (US), ICTM (rest of the world)<br />

and China. At the same time, he finds a great deal of overlap. He proposes to bring<br />

these together through a different way of categorizing sound-based and contextbased<br />

music research, broadening the scope of what we usually consider applied<br />

work.<br />

Xiao Mei and Yukun Wei add a thoughtful historical analysis and critique of<br />

the role of ethnomusicologists in shaping performance formats for traditional musics<br />

in China, predating much work on “artistic research” in Europe and the US (e.g.<br />

Coessens, Douglas & Crispin 2009; Borgdorff 2012). The chapter offers one of the<br />

most lucid and honest accounts of the prevalent way of presenting music traditions<br />

in China I have come across in English. This is combined with critical reflections<br />

on the implications of different ways of engaging ethnomusicologists in the<br />

cataloguing, archiving, bringing to the stage and sustaining of the music practices of<br />

both Han people and Chinese minorities.<br />

In his preface, Seeger mentions that some academics see developing university<br />

curricula as applied work. Certainly, scholars who do research and use it to educate a<br />

next generation of ethnomusicologists (or teachers, or composers, or policy workers)<br />

can claim that they apply their research to a certain extent. And without any doubt,<br />

learning and teaching is an important area of activity for applied ethnomusicologists,<br />

many of whom have another foot firmly in the sister discipline of music education<br />

(Patricia Shehan Campbell comes to mind first, particularly her Global Music Series<br />

with Oxford, and her World Music Pedagogy series with Routledge). Several<br />

contributors to this volume focus on the role and impact of applied ethnomusicology<br />

on music education. Wei-Ya Lin reports on her work for Music without Borders, a<br />

project aiming at creating greater sensitivity to diversity among elementary and

The Vibrant and Diverse Practices of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 9<br />

middle school students in Austria, as part of a national awareness that curricula have<br />

largely remained hegemonically Western in content and pedagogy. But, as she notes,<br />

much work needs to be done to before “the European educational background and<br />

the relative lack of life experience of the teachers, coupled with rigid school rules and<br />

poor communication” makes room for truly “building a bridge for communication.”<br />

Zhilian Feng reflects on her efforts to integrate the Dongbei Dagu tradition into<br />

curriculum of a local conservatory as an “example of how ethnomusicological<br />

research into the nature and status of a traditional music in Northeast China can<br />

be applied to concrete plans to transform the curriculum of a local conservatory”:<br />

a practice that is seen across China and has already lifted the status of many “folk<br />

traditions.” Pepetual Mforbe Chiangong and Nepomuk Riva describe how<br />

facilitating an applied theatre workshop in a West African Graduate Programme with<br />

participants from across the region raises important questions about sustainability,<br />

juxtaposing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals with the indigenous<br />

perspectives of the participants on keeping culture vital.<br />

Cultural sustainability probably emerges as the most prominent theme in this<br />

volume, largely driven by the unparalleled investment China has made into this area<br />

since the 2003 UNESCO Convention on the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural<br />

Heritage. Tony Seeger makes the important distinction between short term and<br />

long-term sustainability, and laments how many of our projects focus on shortterm<br />

outcomes due to funding requirements and university structures. He pleads for<br />

a greater understanding of power structures and the need to aim for sustainability:<br />

“We need to continually think in the long term and do our best to ensure that our<br />

best thinking, our best recordings, and the idea and artistry of those with whom we<br />

collaborate and co-produce are all managed for a future we will not live to see and<br />

that we cannot imagine, but that we can hope to influence.”<br />

Yuh-Fen Tseng describes the challenges and successes in protecting Uyas<br />

Kmeki of the indigenous Seediq in Taiwan, presenting an innovative composition<br />

and performance project in an effort to preserve the music against the background<br />

of a turbulent history, from Japanese colonisation to the present frameworks to<br />

promote indigenous cultures in China. Gao Shu presents the concept and modus<br />

operandi of the National Cultural Ecosystem Protection Areas, which she describes<br />

as “a systematic and appropriate intervention in time and space, intergrating<br />

culture and environment, including entities such as natural set-up, production and<br />

lifestyle, economy, language, social organization, as well as ideologies and value<br />

concepts.” Realising the risk of stasis in such efforts, she reminds the reader that<br />

“the constituent elements are dynamic, balancing the present with the past, distinct<br />

cultures with their wider contemporary contexts, and individual cultural identities<br />

with interaction with a multicultural and networked world.”<br />

The third main theme of applied ethnomusicology that is represented here–<br />

and one that has featured prominently from the beginning–is contributing to<br />

improving the lives of the people applied ethnomusicologists work with. Using his

10 Introduction<br />

work in South Africa as an example, Bernhard Bleibinger makes a contribution<br />

to theoretical discussions by arguing for distinguishing the terms outreach, inreach<br />

and transreach in working with communities. He characterises the latter as “a<br />

specific form of outreach, in which knowledge and/or skills from one or several<br />

cultures are brought to a community consisting of members of another or several<br />

other cultures,” which he considers to be particularly effective in “increasingly<br />

pluri-cultural societies during a time of world-wide migration and transcultural<br />

encounters.” In another challenging cultural encounter, Matthias Lewy reflects<br />

on the absence of indigenous input in an exhibition at an ethnographic museum in<br />

Switzerland, which he tries to counter through the development of sound narratives<br />

in the exhibition halls. He argues for more collaborative curating: “offering this<br />

curative power to the indigenous hands is an act of genuine decolonisation, not<br />

only for the ethnographic museums, but also for our work as ethnomusicologists.”<br />

Dan Bendrups, Robert Burns and Henry Johnson describe their involvement in<br />

developing the music for a wayang kulit video Rama and the Worm with dalang Joko<br />

Susilo to make communities in Java aware of the need for hygiene. Using “nonidiomatic”<br />

improvisations, they create a performance that “exists as a result of interand<br />

transcultural collaboration, offering new sounds and cultural modalities to<br />

accompany a local yet global tradition.”<br />

The powerful final chapter describes musical gatherings to support the<br />

struggle against killing Black people in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, focusing on the<br />

music video Quilombo, Favela, Rua which they produced. Set against a harsh<br />

background of racism, discrimination, genocide, and misogyny, but also providing<br />

perspective by linking it to the spiritual world of the ancestors, they consider the<br />

Sarau Divergente “as a space of healing which strengthens, builds, and concretely<br />

makes visible the political struggle of black resistance.” The chapter is written by<br />

the Ethnomusicological Research Group Dona Ivone Lara, consisting of five<br />

activists and members of the communities, only two of whom are academically<br />

trained. Yet, they are all credited equally, because their contributions are valued<br />

so: a powerful turn from the practice of regarding those who do the musicking as<br />

“informants” or “subjects.”<br />

That leads us to some final reflections on methodology and scope. While,<br />

as this volume demonstrates, applied ethnomusicology covers a wide range of<br />

practices, many would argue that its distinctive features include a degree of agency<br />

on the part of the ethnomusicologist. In other words: the object of study doesn’t<br />

play out before the researcher, but—at least in part—because of the researcher. Pettan<br />

(for instance in the chapter by Boyu in this volume, and in Pettan 2008; Pettan<br />

& Titon 2015) emphasises the term intervention. In the meetings of the ICTM<br />

working group, we have tried to favour presentations which clearly demonstrate<br />

an applied component in their approach: the “intent to apply.” With that intent<br />

arise many new ethical issues, even more intense than the many considerations that<br />

govern ethnomusicological research at large, as they emphatically deal with our

The Vibrant and Diverse Practices of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> 11<br />

roles as agents in relation to the communities we work with, and the intended and<br />

unintended consequences of our actions: “What are we trying to do?”, “In who’s<br />

interest?”, and “Who are we to intervene?”<br />

At the same time, it is useful to realise that much research is not necessarily<br />

either applied or not: it can have any number of applied aspects. This is partly<br />

steered by the environment in which we work: in many academic settings, pure<br />

research is privileged, while for non-academic organisations and many funding<br />

bodies, applied work is. Some research may not be designed to be applied, but turns<br />

out applied later. Some research may be designed to be applied, but turn out to be<br />

more observation-based in the end, for instance when communities choose not to<br />

engage with the applied intentions of the researchers. The way projects are reported<br />

tend to strongly reflect context and intent: there is a vast difference between a peerreviewed<br />

article and a report to inform funding bodies or public authorities.<br />

What does all of this mean in the quest to define applied ethnomusicology,<br />

which a number of contributors to this volume refer to, particularly in Boyu’s<br />

chapter? (in addition to many colleagues over the past 30 years, including Sheehy<br />

1992; Pettan 2015, Pettan & Titon 2015, and particularly Klisala Harrison, who has<br />

emerged as the leading chronicler of applied ethnomusicology: e.g. Harrison 2012,<br />

2016, 2017). I am always a little hesitant when the discussion goes in that direction,<br />

and not convinced that a satisfying and universally applicable definition can or<br />

even needs to be found. What is more important is that we keep discussing the<br />

scope, methods and aims (to invoke Adler 1885) of applied work in our discipline.<br />

Rather than formulating rigid boundaries between applied and non-applied (pure?)<br />

ethnomusicology, I think it is more useful to consider the field as a continuum, with<br />

projects possessing a lower or higher component of “appliedness,” starting with<br />

projects that are barely applied (like, for instance measuring intervals) and ending<br />

at projects where the societal impact may be more important than the musical<br />

sound itself (like in the Brazilian chapter mentioned above). The position on this<br />

continuum does not determine the overall merit or value of research in any way. But<br />

to me, applied ethnomusicology does constitute a powerful reminder of how we can<br />

pursue humane and sensible ways of working with people in ethnomusicological<br />

research, with scholarly rigour and our eye on larger societal contexts.<br />

In their striking diversity in content and approach, the contributions to this<br />

volume embody that, marrying passionate engagement with lucid perspectives.<br />

As Seeger notes in his preface, one of the most striking features of this volume is<br />

the depth of reflection—including critical self-reflection—we see amongst the<br />

authors. I believe it is this that will help applied ethnomusicology most: not a search<br />

for rigid definitions, but rather a continuing, collaborative, collegial, openminded<br />

search among the academic, societal, ethical, organisational, and methodological<br />

issues we all encounter to work most successfully with communities across the<br />

globe to achieve their and our goals in keeping music practices vibrant and alive for<br />

generations to come.

12 Introduction<br />

References:<br />

Adler, G. (1885). Umfang, Methode und Ziel der Musikwissenschaft. Vierteljahresschrift fur Musikwissenschaft<br />

I: 5–20.<br />

Borgdorff, H. (2020). The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden:<br />

Leiden University Press.<br />

Coessens, K, Crispin, D & Douglas, A. (2009). The Artistic Turn: A Manifesto. Ghent: Orpheus Institute.<br />

Harrison, K, Mackinlay, E, & Pettan, S. (Eds). (2010). Historical and Emerging Approaches to <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.<br />

Harrison, K. (2012). Epistemologies of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, 56 (3): 505–529.<br />

—. (2016). <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in Institutional Policy and Practice. COLLeGIUM, 21, University<br />

of Helsinki.<br />

—. (2016). Why <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>? COLLeGIUM, 21: 1–21, University of Helsinki.<br />

Pettan, S. (2008). <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and Empowerment Strategies: Views from Across the<br />

Atlantic. Musicological Annual (special issue on applied ethnomusicology), 44(1): 85–99.<br />

Pettan, S. & Titon, J. T. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford Handbook of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, pp. 29–51. New<br />

York: Oxford University Press.<br />

Schippers, H. (2020). The Meeting Room as Fieldwork Site: Toward an Ethnography of Power. In<br />

Garcia Corona, L.F. & Wien, K., (Eds.), Voices of the Field: Pathways in Public <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, pp.<br />

33–45. New York: Oxford University Press.<br />

Sheehy, D. (1992). A Few Notions about Philosophy and Strategy in <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

(special issue on music, the public interest, and the practice of ethnomusicology), 36(3):<br />

3–7.<br />

Huib Schippers is Adjunct Professor at Griffith University and a consultant for academic and arts organizations,<br />

drawing on over 30 years in leadership positions.

Part One<br />

General Reflections on the Field

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in China and Beyond:<br />

Dialogues and Reflections<br />

Boyu Zhang<br />

Introduction<br />

The concept of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is relatively new in China. Yet at the<br />

same time it is ancient. The idea that music can be used for the benefit of society<br />

has a long history here. According to Confucius, “to change the customs of a<br />

society, nothing is better than music. 1 ” So when he wanted to have a general<br />

understanding of a community, he investigated the nature of music people listened<br />

to 2 . As Yu Hui mentions below, over two millennia later, in 1942, Chairman Mao<br />

gave a speech at Forum on Literature and Art in Yan’an (the birthplace of the Chinese<br />

Communist Party), where he put forward a utilitarian policy that all arts should<br />

serve ordinary people. In contemporary Chinese society, artistic life of the people<br />

is considered part of government responsibilities: not only in terms of the social<br />

administration structure of people who work on music—such as Culture Ministry<br />

at national, the Culture Bureaus at provincial and regional, and Cultural Stations<br />

at county level—but also regarding activities organized by other administrative<br />

offices to enrich people’s cultural lives. A striking example of this is Songxi Xiaxiang<br />

(providing Chinese opera performances to villagers). This is a project managed by<br />

local authorities, who sign contracts and pay opera troupes for free performances<br />

in local villages. The initiative aims to enrich cultural life in remote villages. From<br />

this perspective, the term <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> may be new, yet using music to<br />

improve people’s life is an old and generally accepted practice in China.<br />

Looking back at Chinese music research over the past five decades, its main<br />

purpose was to explore the horizon of music, so as to work out the specific rules<br />

and characteristics of Chinese traditional music, with a view of offering such data<br />

1. 移 风 易 俗 , 莫 善 于 乐 。This is a wide spread idea being believed said by Confucius. The sentence is recorded<br />

in the ancient book Xiaojing-Guangyaodao (Filial Piety 《 孝 经 》, Section on “Principles Expanding”), which is<br />

one of Thirteen Classics of Confuciunism.<br />

2. In ancient China, every Dynasty had its own court music system which was considered as part of political and<br />

social system. This information can be found in the “Music Section” of 24 Annals. For example, in the Lushi<br />

Chunqiu, a historical book written two thousand years ago recorded that Huangdi (Yellow Emperor) asked music<br />

officers to make temperament pipes in order to measure the tuning system..

16 Part One: General Reflections on the Field<br />

to composers to work out new compositions with a Chinese character 3 . Hence,<br />

ethnomusicological research was treated at the time as part of compositional<br />

process, and the researchers were based in the Composition Department of<br />

the Conservatories. Music research was therefore “applied” to composition<br />

in art music. It is much later—in the 1980s—that Chinese music research, or<br />

research of music from a cultural perspective, or ethnomusicology, came into<br />

existence as an independent entity in China. There are still debates among<br />

Chinese ethnomusicologists on the definition of Chinese music research versus<br />

ethnomusicology, or the study of music in a cultural context versus and that of<br />

pure music analysis. Since 2004, following the guidelines of the 2003 UNESCO<br />

Convention on the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, the Chinese<br />

Government and scholars have been emphasizing the heritage of “music traditions in<br />

China.” Research now encompasses many processes of dealing with “raw materials,”<br />

such as collecting, archiving, research, publication, restoration, preservation,<br />

introducing folk music to university (education), and last but not least, using<br />

musical expression to bolster tourism. The Intangible Cultural Heritage Office has<br />

become part of the official establishment at all levels of social management: County,<br />

Region 4 , Province, and the National.<br />

We can therefore conclude that in China, ethnomusicological research and<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> have always been intertwined to some extent. Research<br />

is considered useful for addressing social problems, through raising the awareness<br />

of cultural heritage, and enhancing the understanding of the value of the tradition.<br />

As opportunities for education have improved, illiteracy has almost disappeared<br />

in China. This has allowed folk musicians from remote areas to write about their<br />

own music, thereby promoting the dissemination of indigenous music to outsiders.<br />

Such articles are readily available on websites, such as the websites of the Intangible<br />

Cultural Heritage Offices of counties and provinces. While some of these may not<br />

have a high research value, they can still offer some basic information to the readers.<br />

With these ideas in mind, I felt the Joint Symposium of the ICTM Study<br />

Groups on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> (6 th ) and Music, Education and Social<br />

Inclusion (2nd), which I convened with my team in Beijing in July 2018, was the<br />

ideal opportunity for a dialogue between leading Chinese and Western (Europe<br />

and US-based) applied ethnomusicologists on what Huib Schippers refers to (after<br />

Adler 1885) as the “Scope, Methods and Aims of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” in his<br />

Introduction to this volume. I was very fortunate to have Professors Xiao Mei, Hui<br />

Yu, Svanibor Pettan, Anthony Seeger, and Huib Schippers willing to take part in<br />

an onstage dialogue with me. This chapter is a primarily a report of that dialogue,<br />

which took place on July 9 th , 2018.<br />

First, after my introductory remarks on applied ethnomusicology in China<br />

described above, it may be useful to revisit some Western perspectives. In the US,<br />

3. This approach strongly resonates with what is now mostly referred to as “artistic research”, which was one of the<br />

themes of the 7 th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group in 2020.<br />

4. Region indicates several counties to form a “county cluster”, and named with a city within the area.

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in China and Beyond: Dialogues and Reflections 17<br />

the Society for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> (SEM) was the first organization to dedicate a<br />

Section to <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, in 1998. On its website, its focus is outlined as<br />

follows:<br />

The <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Section is devoted to work in ethnomusicology<br />

that puts music to use in a variety of contexts, academic and otherwise, including<br />

education, culutral policy, conflict resolution, medicine, arts programming<br />

and community music. Members in applied ethnomusicology section work to<br />

organize panel sessions and displays at SEM conferences that showcase this kind<br />

of work and to discuss the issues that surround it, as well as to foster connections<br />

between individuals and institutions.<br />

(https://www.ethnomusicology.org/page/Groups_SectionsAE, accessed 10 July 2021)<br />

The ICTM Study Group on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> was officially established in<br />

2007, and the following definition of the field can be found on the ICTM website:<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is the approach guided by principles of social<br />

responsibility, which extends the usual academic goal of broadening and<br />

deepening knowledge and understanding toward solving concrete problems and<br />

toward working both inside and beyond typical academic contexts.<br />

(http://www.ictmusic.org/group/applied-ethnomusicology, accessed 10 July 2021)<br />

The definition on SEM website focuses mainly on the “public sector,” such<br />

as festival and concert organization, museum exhibitions, and apprenticeship<br />

programs, as well as the scholarship embraced by SEM that addresses these topics;<br />

whereas the definition on ICTM website refers to addressing of concrete social<br />

issues, and towards working both inside and beyond typical academic contexts.<br />

These aims and objectives are not mutually exclusive. The differences between<br />

these two organizations seem to be that SEM focuses on work on festivals, concert<br />

organization, etc., while ICTM is broader and it prioritizes the “social issues”<br />

and “concrete problems.” This is why <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is defined as an<br />

“approach” rather than a (sub)discipline. For ethnomusicologists involved with either<br />

SEM or ICTM, not many have the opportunity to serve as organizers of festivals or<br />

concerts. When these scholars discuss issues related to such boundaries, as mentioned<br />

in the last sentence of SEM’s definition, what differences can be found between<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>? In any society, job positions are<br />

usually geared toward certain categories of people. Ethnomusicologists usually work<br />

at universities: if they want to apply their knowledge to address certain social issues,<br />

or to organize festivals, or similar events, do they complete those tasks as part of<br />

their work or independently? Or do they offer their wisdom to those who work in<br />

these fields? When scholars such as the panelists in this round table discuss the issue,<br />

is the discussion part of applied ethnomusicology, or rather theoretical?<br />

These are ongoing discussions around the world. The SEM Section tends to<br />

have a US focus, while the first five symposiums of the Study Group on <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>—which took place in Europe, Africa and Asia—scholars were<br />

trying to get closer to a shared understanding of the elusive meaning of <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>; sometimes agreeing, sometimes agreeing to disagree. A number<br />

of important scholarly contributions have emerged from these discussions, from

18 Part One: General Reflections on the Field<br />

Sheehy and Titon’s 1992 reflections in <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> to the more in-depth edited<br />

volumes <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>—Historical and Contemporary Approaches (Klisala<br />

Harrison, Elizabeth Mackinlay and Svanibor Pettan, eds, 2010); The Oxford Handbook<br />

of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> (Pettan and Titon 2015); and <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in<br />

Institutional Policy and Practice (Harrison 2016), to name just a few.<br />

The Panel Discussion<br />

However, the focus of this chapter is not the scholarly literature, but rather the lively<br />

exchange on the subject by the scholars mentioned above, which on the following<br />

pages includes their—slightly edited—contributions to the panel discussion and<br />

their responses to questions from other participants of the conference in Beijing. In<br />

their statements, the five panelists reflect on their views, experiences and visions for<br />

applied ethnomusicology in the order they spoke at the event. I will present these<br />

insights as they were delivered during the Symposium, and reflect on some of their<br />

implications towards the end of this chapter.<br />

Svanibor Pettan:<br />

The definition of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, which probably all of you know already<br />

[see also above] was adopted at the ICTM World Conference held in Vienna in<br />

2007, and since then it was used at various ICTM-related events. Back then, I called<br />

for a meeting and presented some basic suggestions how to define this field, and<br />

our collective brainstorming resulted in the current definition. I would like to alert<br />

you that it is possible to compare the definitions in different institutions, such as<br />

SEM and ICTM. ICTM was established in 1947, while SEM a bit later in 1955.<br />

The Section on <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> at SEM was established in 1998, while<br />

at ICTM the Study Group was established in 2007. Interestingly, though, on the<br />

SEM website there was no definition for a long time; it only offered quotations from<br />

different scholars explaining what <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> involves.<br />

The question is: what does <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> mean for me, or for each<br />

of us? I always sensed compassion, as I wanted my research to help solving problems<br />

and to have a broader meaning. For me, the notion of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is<br />

like a dream come true. This was the reason behind the establishment of this study<br />

group, and I am happy to see the group steering in its current directions. I was<br />

also a founding member of SEM <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Section. I attended its<br />

meetings, and at the beginning there was a tendency to discuss non-academic job<br />

opportunities for ethnomusicologists. It was about the public sector, for instance<br />

people working in museums rather than having university positions. In the 1990s,<br />

I was experiencing “war at home” and my research was focused on work. I was<br />

dealing with refugees and other people facing questions of life and death. I was not<br />

really satisfied with the scope of our discipline which, I felt, was not living up to its<br />

potentials. This motivated me to became involved in establishing a study group at<br />

ICTM.<br />

There are scholars who are satisfied with doing research for the purely academic<br />

purposes. They do not like to talk about application; some are actually unhappy

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in China and Beyond: Dialogues and Reflections 19<br />

about it. Alan P. Merriam and later Bruno Nettl wanted to primarily secure the space<br />

for ethnomusicology as an academic discipline in US curricula. In Nettl’s historical<br />

overviews of the discipline, there is no mention of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

from which we can see that their history of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> does not mention<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. Why is it so? Anthropology, sociology, not to mention<br />

mathematics, physics, etc., are accompanied by their applied branches. There are<br />

even independent scholarly societies with a focus on application of their disciplinary<br />

legacies. The Society for <strong>Applied</strong> Anthropology, for instance, has more members<br />

than the primary disciplinary organizations such as Society for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> or<br />

ICTM. All of them are using the knowledge, understanding, and skills developed in<br />

the respective disciplines for the sake of practical improvements.<br />

The key word here is “intervention”, i.e. reaching beyond the broadening<br />

and deepening of knowledge for the sake of either change or safeguarding of the<br />

circumstances. In Slovenia, the predominant model of ethnomusicology in public<br />

perception is that of folk music research, which is very much nationally selfcentered.<br />

In the 21 st century, this historical search for the nation’s pure soul in old<br />

village songs is giving space to the inclusion of minorities and encounters with<br />

various other musics in general. There are potential applied extensions of research<br />

based on collected songs, dances, or music instruments in the field ethnographies,<br />

transcriptions in staff notation, and recordings. But now, I also raise the awareness<br />

about <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> through the course at the University of Ljubljana. I<br />

think this is one of our great achievements.<br />

In Austria, which is the neighboring country of Slovenia, there are clear traces<br />

of both historical traditions of ethnomusicology: comparative musicology and<br />

folk music research. In my article in The Oxford Handbook of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

(2015), I pointed out that <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> can differ from country to<br />

country, from continent to continent. Where does <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong><br />

start? Again, I think the notion of “intervention” is central. The boundary between<br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> and <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> is conditioned by the researcher’s<br />

conscious decision that we decide to use his or her knowledge, understanding, and<br />

skills to make a difference. This is at least very clear to me. In the International<br />

Musicological Society and the American Musicological Society, there are no applied<br />

sections so far, while the notion of “applied music” refers to performance. <strong>Applied</strong><br />

ethnomusicologists talk about people, often underprivileged ones, and use of music<br />

and ethnomusicological knowledge for the sake of improvements.<br />

Moreover, we do not favor top-down projects; The knowledge generated in our<br />

discipline results from our communication with the people in the field. I would like<br />

to address this as something which is not emphasized enough; while we do generally<br />

favor a bottom-up approach and close collaboration with our partners in the field,<br />

we realize that the communities we are dealing with are not necessarily harmonious.<br />

Different voices require negotiations, sometimes involving bottom-up, sometimes<br />

top-down solutions. We are keeping it in process. Should successful <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> projects be recognized by academia as something comparable<br />

to publications? I think so. I see a great future for <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. We

20 Part One: General Reflections on the Field<br />

should have more applied projects and more publications; projects that can make a<br />

difference in humans’ lives, change their circumstance for the better.<br />

Anthony Seeger:<br />

I will speak from the United States perspective. I specify this because I think we<br />

will find that different countries have different ideas about the definition of <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. I am concerned about the lack of clarity in the word “applied”.<br />

We have the word in English, however, and I don’t think I can change its use in<br />

the term “applied ethnomusicology.” The Society for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>’s <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Section recently refined its definition (see citation above). Yet<br />

problems remain with the use of the word. In the United States, the words “applied<br />

ethnomusicologist” are often used to refer to ethnomusicologists who work outside<br />

academic institutions.<br />

However, today many university teachers are also working on applied projects<br />

outside their universities. Some of my UCLA colleagues disagreed that applying<br />

ethnomusicology was confined to work outside the university. They said “We do<br />

applied ethnomusicology every day. We are applied ethnomusicologists when we<br />

prepare a course syllabus; we are applied ethnomusicologists when we give lectures.”<br />

So they did not want the term “<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>” to be used the narrower<br />

ICTM definition or the frequent use of the term for ethnomusicologists working<br />

outside academic life. Some of my colleagues preferred using the term “public<br />

ethnomusicology” or “public-facing ethnomusicology” for the activities listed<br />

by the <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> Section (Corona and Wiens 2021). In the US,<br />

social responsibility is not used as a criterion for applied ethnomusicology projects.<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists use their knowledge for many kinds of activities.<br />

In the US the definition of the field is broader than the ICTM’s definition (the<br />

definition cited above, accessed 13 July 2021). <strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists in the<br />

US can work for a record company, as radio producers, or on music festivals. I do<br />

think that there should be more interaction between professionals who are working<br />

in public-facing jobs, doing things such as creating festivals, or engaging in socially<br />

responsible activist projects, and those who are teaching at universities. <strong>Applied</strong><br />

ethnomusicology can improve ethnomusicological theory; and theory helps and<br />

improves applied projects. <strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicology has an important place in the<br />

field of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, and the field as a whole can have a role in improving the<br />

success of those working on applied projects.<br />

I think different countries, by virtue of their political histories and institutions,<br />

can have different engagements with applied ethnomusicology. In the United States,<br />

universities were seriously attacked by right wing politicians in the 1950s (and again<br />

in recent years). To protect themselves, universities became very conservative and<br />

many discouraged public engagement. That may be one reason that the founders of<br />

the Society for <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in the 1950s did not include an applied emphasis<br />

in their discussions of the word ethnomusicology.<br />

One of our African colleagues asked whether securing a grant to create a music<br />

drama and organizing university students to perform in public to teach people how

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> in China and Beyond: Dialogues and Reflections 21<br />

to avoid HIV is <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. I think it is applied ethnomusicology<br />

in the sense of “applying” your understanding of the music and the importance<br />

of drama to create that activity. In some circumstances we are involved in applied<br />

musicology, theater, and <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. But when you present papers and<br />

write about what you are doing, then you become part of the discourse of<br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>.<br />

We reached several levels of discussion in this Symposium. I have been very<br />

impressed that people in this Study Group meeting are not just reporting what they<br />

did, but also reflecting seriously on the consequences, good or bad. The level selfcriticism<br />

has been really excellent. There is something very exciting about <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>. This is partly because we are all thinking so hard about important<br />

issues, not just what we are doing, but on ideas we have in our own minds and have<br />

learned from the people we are working with.<br />

Finally, I think it is important to remember that applied ethnomusicologists<br />

are people who take the training and understanding of music they learn through<br />

ethnomusicological study and research to work with individuals and communities<br />

to help them attain something they want to accomplish. But ethnomusicologists also<br />

take what they they learned back to institutions of which they are part, to transform<br />

universities, their countries, their lives, and the lives of others on this planet.<br />

Huib Schippers:<br />

While I have also worked in Asia, Australia and the US, I come from The Netherlands,<br />

a country with a strong basis in colonialism. Colonial thought was at the<br />

basis of how early ethnomusicologists thought and worked throughout Western<br />

Europe. The person who invented the word <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> was my compatriot<br />

Jaap Kunst, who did a great deal of work to help people understand music from<br />

other cultures, particularly Javanese and Balinese Gamelan. But as his student Ki<br />

Mantle Hood told me, Kunst probably never touched Gamelan: He was part of the<br />

colonial system and would never sit down with the “natives” and play their music.<br />

So the person who many consider as a founder of our discipline—and an expert on<br />

Gamelan—never touched Gamelan.<br />

A good number of us from that side of the Atlantic, who are now called<br />

applied ethnomusicologists, including myself, have a background in working<br />

with communities outside of academia. I set up music schools, was involved<br />

in policy development, ran a record shop, organized festivals, and worked as a<br />

music critic (see also my Introduction to this volume). I did all of these things<br />

before I considered being an ethnomusicologist. As both Tony and Svanibor said,<br />

<strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> existed long before we started the first discussions in<br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> like Sheehy’s and Titon’s 1992 articles, and long before 2003, when<br />

China started embracing the work on Intangible Cultural Heritage which we now<br />

consider a very important aspect of <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>.<br />

I think that much <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> could be more “applied” in its nature.<br />

It follows logically from what we are as people and as scholars who care for<br />

communities we work with, and I am very pleased to see what we have started

22 Part One: General Reflections on the Field<br />

to think about this deeply. There were a lot of discussions on ethical issues in this<br />

Symposium, which represent a shift from seeing the people we work with from<br />

subject to informant, from collaborator to co-researcher, and now many of us work<br />

towards social justice and inclusion: we’ve moved from people working for us to<br />

working with people or working for people. <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> implies that<br />

we are giving our work back to communities in a meaningful way.<br />

It is really interesting to see that we are getting into the discussion on how<br />

this fits in the institutions we work for. There was a question about hierarchies of<br />

knowledge at funding organizations, who favor applicants whose research projects<br />

lead to “new knowledge.” It is true that we still have a long way to go in many<br />

countries towards equivalence of applied research. However, if you look at the<br />

entire funding landscape, it is usually easier to find money support for applied<br />

projects because they can demonstrate impact. Many governments now also have<br />

“impact” on their agenda for research, which is what we tend to deliver on. And<br />

it’s our responsibility to talk to the institutions about what is happening in society.<br />

Institutions and governments have the responsibility to react to change, and to create<br />

frameworks to accommodate new realities. <strong>Applied</strong> ethnomusicologists can assist in<br />

those efforts.<br />

Hui Yu:<br />

If I want to answer the question “What is <strong>Applied</strong> <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>?” I probably<br />

would say it is an academic branch based on our ethnomusicological knowledge to<br />

make visible improvements in our society through either theoretical investigation<br />

or practical social activities. As many Chinese scholars have already been confused<br />

with the imported term of <strong>Ethnomusicology</strong>, the relatively new concept of <strong>Applied</strong><br />

<strong>Ethnomusicology</strong> would undoubtedly bring many debates and discussions. Before<br />

ethnomusicology was introduced to China, traditional Chinese music research<br />

was called minzu yinyue lilun, or “theory of national music” in many high learning<br />

institutions, which was also the name of an undergraduate major at Shanghai<br />

Conservatory. When ethnomusicology became popular, some music scholars<br />

considered their endeavor part of ethnomusicological research. Others believe the<br />

purpose of their work is to establish a Chinese music theory system parallel to the<br />

Western one, based on the unique features found from the traditional music by the<br />