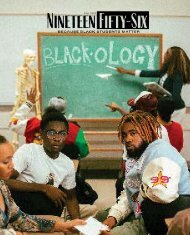

Nineteen Fifty-Six Vol.4 Issue 2

Our latest magazine issue, Rooted, delves into the complexities surrounding the black family and the stigmas that often accompany conversations about it. From generational trauma to stereotypes perpetuated by the media, we examine the challenges faced by black families and the resilience and strength that bind them together. However, Rooted also celebrates the beauty and richness of black family life and culture, showcasing the love, unity, and traditions that make these families truly unique. Join us as we explore the multifaceted narratives of the black family and honor their history and heritage.

Our latest magazine issue, Rooted, delves into the complexities surrounding the black family and the stigmas that often accompany conversations about it. From generational trauma to stereotypes perpetuated by the media, we examine the challenges faced by black families and the resilience and strength that bind them together. However, Rooted also celebrates the beauty and richness of black family life and culture, showcasing the love, unity, and traditions that make these families truly unique. Join us as we explore the multifaceted narratives of the black family and honor their history and heritage.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

a food pantry, clothing back and basketball court where<br />

they host community activities.<br />

There’s also a community garden where they harvest and<br />

give away food, even allowing people to have their own<br />

plots, though it is currently closed due to construction.<br />

Doughty-Walker said as long as she could remember<br />

her family has had a “servant’s heart” and a passion for<br />

the Tuscaloosa community, specifically those who were<br />

underserved. She said they would use what they had as<br />

a resource before they could carry out their ministry<br />

through the shelter.<br />

She said before they created the shelter, there would be<br />

nights when her dad would open their house for people to<br />

sleep overnight when it was too cold outside.<br />

“So, it’s kind of evolved from helping people at home into<br />

this massive ministry of God is doing through us for the<br />

community,” Doughty-Walker said.<br />

Sheyann Webb-Christburg is also no stranger to serving<br />

her community and being a mother to many. From Selma,<br />

she is now primarily based in Montgomery, Alabama, and<br />

is known as Martin Luther King Jr.’s “smallest freedom<br />

fighter.”<br />

While describing her proximity to the Civil Rights<br />

movement, Webb-Christburg emphasized the need for<br />

courage and how our Civil Rights leaders sacrificed so<br />

much during the movement.<br />

“You have to have courage, and they had to not only have<br />

courage but they made a lot of sacrifices,” she said. “People<br />

left their homes; they left their children.”<br />

She understood the need to do what was right even if it<br />

was something she did not like. She said it took “a great<br />

deal of determination and commitment.”<br />

Still determined and committed, Webb-Christburg<br />

started a youth program called KEEP Productions in 1980,<br />

which still exists today, making it 42 years old.<br />

“I started my own youth development program to help<br />

young people to build self-esteem, to inspire and motivate<br />

them, and to really impress upon them based on my<br />

experiences that they did matter,” she said.<br />

Christburg said she considers herself a mother of the<br />

community— a mother of change, who has been able to<br />

help create a ripple effect of change through her program.<br />

“I have seen the reality of it in many ways when over<br />

thousands of young little girls and little boys and they’ve<br />

moved on to do positive things to become educated,”<br />

she said. “And I still see them as adults now, and they are<br />

change agents in their own rightful age wherever they<br />

are.”<br />

Yet, in the conversation about “mothers of the<br />

community,” some people are overlooked and left out<br />

of the conversation, specifically those in the LGBTQ+<br />

community.<br />

Lauren Jacobs, a UA alum and assistant director of Magic<br />

City Acceptance Center, said she doesn’t think LGBTQ+<br />

people are uplifted when they should be, in general, let<br />

alone in conversations of community engagement and<br />

even within the LGBTQ+ community, there are “mothers<br />

of the community” who have had significant impacts on<br />

history who are at times ignored from the conversation<br />

like Martha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two trans women<br />

of color who were pivotal figures in the Stonewall Riots.<br />

“If we’re making a really inclusive understanding of<br />

what [mothers of the community] means, does it include<br />

trans women? Does it uplift BIPOC trans women? Does<br />

it celebrate— not just like, accept, but actually celebrate<br />

Black and brown, queer, and trans folks? Not enough, no,”<br />

she said.<br />

Nabila Lovelace, a writer, poet and instructor<br />

in the University’s gender and race studies<br />

department, challenged the title of “mothers of<br />

the community” and instead offered “caretakers<br />

of the community” because a crux of community<br />

work is not done by a singular group of people<br />

but by the intergenerational connection of elders,<br />

queer spaces and children.<br />

45