Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

6<br />

Photo by Larry R. Wagner<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> <strong>Driver</strong><br />

rock art and bottlecaps:<br />

jewelry from found objects<br />

by Peggy Templer<br />

If you tossed a beachcomber/scavenger/naturalist,<br />

the inventor of the Rubik’s cube, one of the elves from<br />

Santa’s toyshop, and a slightly mad scientist into a very<br />

large blender and extracted the DNA, you’d get <strong>Dana</strong><br />

<strong>Driver</strong>. Technically, however, she’s a metalsmith and<br />

jeweler whose imaginative and intricate work is not only<br />

beautiful, but makes you smile. Only <strong>Dana</strong> would put<br />

wheels on rocks, flatten bottle caps into brooches, and use<br />

her sense of humor as a main design impetus.<br />

I interviewed <strong>Dana</strong> at her studio in Albion, which is<br />

part jewelry studio and part natural history museum. In<br />

boxes, drawers and shelves are the found objects <strong>Dana</strong><br />

has picked up, intrigued by their design, structure, color,<br />

texture, and the possibilities for incorporating them into<br />

her work. This includes rocks, shells, dried mushrooms,<br />

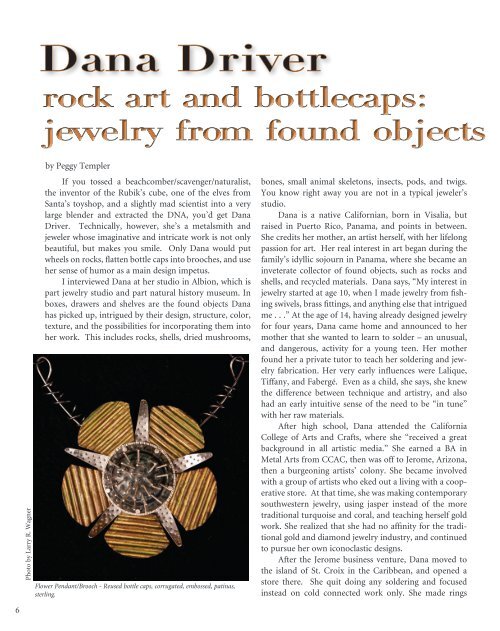

Flower Pendant/Brooch - Reused bottle caps, corrugated, embossed, patinas,<br />

sterling.<br />

bones, small animal skeletons, insects, pods, and twigs.<br />

You know right away you are not in a typical jeweler’s<br />

studio.<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> is a native Californian, born in Visalia, but<br />

raised in Puerto Rico, Panama, and points in between.<br />

She credits her mother, an artist herself, with her lifelong<br />

passion for art. Her real interest in art began during the<br />

family’s idyllic sojourn in Panama, where she became an<br />

inveterate collector of found objects, such as rocks and<br />

shells, and recycled materials. <strong>Dana</strong> says, “My interest in<br />

jewelry started at age 10, when I made jewelry from fishing<br />

swivels, brass fittings, and anything else that intrigued<br />

me . . .” At the age of 14, having already designed jewelry<br />

for four years, <strong>Dana</strong> came home and announced to her<br />

mother that she wanted to learn to solder – an unusual,<br />

and dangerous, activity for a young teen. Her mother<br />

found her a private tutor to teach her soldering and jewelry<br />

fabrication. Her very early influences were Lalique,<br />

Tiffany, and Fabergé. Even as a child, she says, she knew<br />

the difference between technique and artistry, and also<br />

had an early intuitive sense of the need to be “in tune”<br />

with her raw materials.<br />

After high school, <strong>Dana</strong> attended the California<br />

College of <strong>Art</strong>s and Crafts, where she “received a great<br />

background in all artistic media.” She earned a BA in<br />

Metal <strong>Art</strong>s from CCAC, then was off to Jerome, Arizona,<br />

then a burgeoning artists’ colony. She became involved<br />

with a group of artists who eked out a living with a cooperative<br />

store. At that time, she was making contemporary<br />

southwestern jewelry, using jasper instead of the more<br />

traditional turquoise and coral, and teaching herself gold<br />

work. She realized that she had no affinity for the traditional<br />

gold and diamond jewelry industry, and continued<br />

to pursue her own iconoclastic designs.<br />

After the Jerome business venture, <strong>Dana</strong> moved to<br />

the island of St. Croix in the Caribbean, and opened a<br />

store there. She quit doing any soldering and focused<br />

instead on cold connected work only. She made rings

and bracelets of stone and metal,<br />

“not that distinctive from other jewelers,<br />

but very contemporary with<br />

an unusual ‘ancient’ look to them.”<br />

While living on St. Croix, <strong>Dana</strong><br />

became particularly fascinated with<br />

beach stones, basalt, shells and other<br />

‘detritus,’ and began “trying this and<br />

that and my style began to evolve. I<br />

also became very distressed thinking<br />

about the environmental cost of<br />

mining precious stones and metals,<br />

and began using found objects and<br />

beachstones in my work.” She walked<br />

the beaches, searching for and picking<br />

up “anomalies” – shells and rocks and<br />

tiny fish and bird bones – and then<br />

realized the work she wanted to do.<br />

According to <strong>Dana</strong>, this realization<br />

came as an urgent epiphany; she felt<br />

there was no time to lose to begin<br />

doing this work, which was to make<br />

art from natural materials, acquired<br />

by foraging, and to move completely<br />

away from traditional materials. She<br />

also at that time felt a need to be a<br />

part of a larger community of artists,<br />

and moved to the <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

Coast, where her parents, Dan and<br />

Katherine <strong>Driver</strong>, had retired to the<br />

town of Albion. <strong>Dana</strong> then began<br />

the stunning work for which she is<br />

best known, in which she finds, polishes,<br />

carves and drills beach stones<br />

from the Albion shore, and inlays<br />

those with soft metals (gold and<br />

silver) hammered into the carved<br />

designs and fashioned into rings,<br />

brooches, pendants, and small sculptural<br />

pieces. She also began teaching<br />

an extremely popular class, “Primal<br />

Tech Rock <strong>Art</strong>,” at the <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>.<br />

The process of figuring out how<br />

to carve and inlay stone took many<br />

months to “puzzle out,” which is one<br />

<strong>Art</strong>iculated Beetle – brooch-beach stone carved and<br />

inlaid with fine silver, sterling.<br />

Die Pendant – Bottle caps, copper, sterling, 14 kt.,<br />

patinas, fabricated, hinged together and opens to<br />

reveal the message “The Die Has Not Been Cast”<br />

Flamingo Brooch – beach stone carved and inlaid<br />

with fine silver, sterling, 18 kt., Iolite<br />

reason it was so intriguing to <strong>Dana</strong>.<br />

She is always most inspired when<br />

confronted with a challenge – how<br />

can she make this work? How can<br />

she solve the problems inherent in<br />

the designs she is creating? This process<br />

of working to resolve a puzzle<br />

is what keeps <strong>Dana</strong> energized and<br />

keeps her always trying to do something<br />

she has not done before.<br />

Which is how she arrived at<br />

her next challenge, bottlecap jewelry.<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> wanted to “recycle some<br />

material that’s abundantly around,”<br />

and from her long habits of foraging<br />

and staring at the ground,<br />

she realized that “creating jewelry<br />

from found bottle caps, tin cans, and<br />

rusty bits of metal would lessen my<br />

carbon footprint.” Her bottlecap<br />

jewelry is utterly unique – beautiful<br />

and fun.<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> foresees that her next<br />

passion will be automata, which<br />

refers to mechanical toys or “small<br />

sculptures that do stuff.” She loves<br />

the puzzle aspects of simple, basic<br />

mechanical movement, and has<br />

already experimented with her rock<br />

beetles with articulated legs and<br />

wheels.<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> credits Alexander<br />

Calder, whose work she first became<br />

acquainted with while attending<br />

CCAC, with being her “hero” and a<br />

major influence on her own work.<br />

The reason for that is that “everything<br />

he did, it looked like he had a<br />

pretty darned good time doing it.”<br />

And that is every bit as important to<br />

<strong>Dana</strong> <strong>Driver</strong> as it was to Alexander<br />

Calder.<br />

<strong>Dana</strong>’s work can be seen at<br />

North Coast <strong>Art</strong>ists, <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

Jewelry Studio, and on her Web site at<br />

www.danarocks.com<br />

7

8<br />

S H A S H A H I G B Y<br />

International Performance/Sculptural <strong>Art</strong>ist to Perform<br />

at the Matheson Performing <strong>Art</strong>s <strong>Center</strong><br />

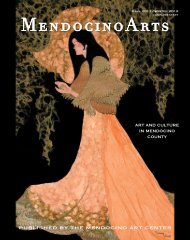

International performance/sculptural<br />

artist Sha Sha Higby is known for her<br />

evocative and haunting performances using<br />

the exquisite and ephemeral body sculpture<br />

she meticulously creates herself and moves<br />

within. Elaborate sculptural costume, dance,<br />

and puppetry explore magic and emotion,<br />

creating an atmospheric world within the<br />

borders between death and life. Ms. Higby<br />

has performed her unique body of work<br />

throughout the United States, and internationally<br />

in Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Slovak,<br />

Bulgaria, Singapore, Australia, Switzerland,<br />

England, Belgium, Germany and Holland.<br />

She is the recipient of numerous grants and<br />

awards. She studied for one year in Japan<br />

in 1971, observing the art of Noh Mask<br />

and theater and then received a Fulbright-<br />

Hayes Scholarship to study dance and shadow<br />

puppet making and performance arts in<br />

Indonesia for five years at the Academy of<br />

Music, Central Java, Indonesia. In addition<br />

to traveling throughout Southeast Asia Photo by Albert Hollander from Folds of Tea<br />

to Thailand and Myanmar (Burma), she<br />

received an Indo-American Fellowship to study the textile arts of India, and a Travel Grants Fund from <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

International to study in Bhutan. She has also recently studied lacquer arts in Tokyo and Kyoto, Japan through<br />

the auspices of the Japan-United States Friendship Commission. *

y Peggy Templer<br />

Sha Sha Higby could easily be the poster child for<br />

the single-child family. An only child until the age of<br />

eleven, this amazingly imaginative artist can trace her<br />

creative development back to the hours she spent alone<br />

in her upstairs bedroom as a child. She was constantly<br />

drawing, making up stories, creating dolls and puppets,<br />

imagining and producing entire travelogues with<br />

forests and trails and other destinations, all within the<br />

confines of her room. Her mother always encouraged<br />

her to indulge her imagination, and had endless<br />

patience for a creatively messy room. Her stepfather<br />

taught her to sew and was handy with tools, so that she<br />

began making things for their home and friends, dolls<br />

with long skinny legs, 100 mice finger puppets, eggs<br />

with scenes inside, stories embellished with costume<br />

and fabric. She also wrote stories and bound the books.<br />

Her mother opened a retail clothing store, but Sha Sha<br />

still made all of her own clothes.<br />

Sha Sha majored in art at Skidmore College, from<br />

which, during her junior year, she participated in an<br />

exchange program to Japan and wound up staying<br />

for one year instead of three weeks. In Japan she was<br />

introduced to many of the elements that would become<br />

features of her own life’s work – Kabuki theater, Noh<br />

mask carving, dance and movement, tea ceremony, calligraphy,<br />

elaborate Shinto and Buddhist rituals and rich<br />

costuming. According to Sha Sha, “Japanese crafts and<br />

Noh Theater, with its elaborate costuming and poetic<br />

structure, were the major influence on my work.”<br />

After returning from Japan, “on her own” as an artist,<br />

Sha Sha began making installation pieces for galleries,<br />

primarily small objects that were a cross between sculpture<br />

and puppetry strung on threads which “involved a<br />

lot of sewing,” as well as the use of carved wood which<br />

she learned from Noh Mask Carving. It was during this<br />

time that she became particularly intrigued with Butoh<br />

Dance performances. “The dancers’ bodies were like<br />

Above: Photo by Albert Hollander from Folds of Gold by Sha Sha Higby. Japanese urushi lacquer, gold leaf, embroidery, silver filigree leaves<br />

9

10<br />

The Song (“Naki Goe”) 12’ by<br />

4.5’ by 4’, mixed media including<br />

Japanese urushi<br />

sculptures and I was<br />

inspired by them to finally<br />

pull all of these elements<br />

together – dancing, movement,<br />

sculpture, puppetry,<br />

costuming and non-linear or<br />

non-verbal story telling.” Her first performance, in which<br />

she essentially mounted her elaborate sculpture on her<br />

back, took place in a private home. Sha Sha recalls this<br />

first performance as “the most exciting thing I had ever<br />

done. Everything all came together.” From then on, she<br />

did a performance a year, but as the costumes/puppets<br />

became more elaborate, the interval between performances<br />

became longer. Now it takes her up to two years to<br />

prepare the puppets and props for a performance. Over<br />

time the performances have become richer, incorporating<br />

more and more different mediums, including Japanese<br />

urushi lacquer, lighting and sound.<br />

Many times after performances, Sha Sha was asked<br />

to do workshops to teach students how to create the<br />

masks and costumes she uses in her unusual visual and<br />

performing art form. She has been a teacher throughout<br />

a few decades of touring, and has taught several times at<br />

the <strong>Mendocino</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>. On October 23rd, she will be<br />

teaching a workshop, “Golden Archetype on a Stick” at<br />

the <strong>Mendocino</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, in which students will learn to<br />

cast, mold and recast theatrical masks, and mount them<br />

on sticks and add wires and ornamentation to make a<br />

spirit catcher.<br />

Sha Sha describes her performances as “like a poem<br />

or a painting with movement,” in which the meaning of<br />

the story is experienced in subtle, non-linear ways. The<br />

performances are choreographed to specific points on her<br />

journey but also spontaneous, like<br />

a drawing, as she dances along her<br />

way. They follow a progression from<br />

beginning to end, but the journey is mysterious<br />

and unscripted.<br />

The audience is an important<br />

part of Sha Sha’s performances. The<br />

audience comes along on the artist’s<br />

journey as, child-like, she<br />

plays with the toys and objects<br />

she comes across, building to a “crescendo<br />

of meaning and discovery,” which is subjective for<br />

each member of the audience. She attempts throughout<br />

the performance to draw her audience in by approaching<br />

them and by providing them with noisemakers, some of<br />

which (bird calls, rattles, etc.) have been made to enhance<br />

the story line, as the audience deems appropriate. After<br />

the performance, the audience is invited on stage to view<br />

the costumes, masks and props.<br />

Sha Sha’s performances are evocative of a child on<br />

a magical journey, discovering things for the first time,<br />

moving from experience to experience, dancing and<br />

exploring through the mysteries of life, as every child can,<br />

just like the child Sha Sha did alone in her upstairs room,<br />

way back in the beginning.<br />

Sha Sha’s work has been featured on the cover of<br />

Ornament Magazine as well as Crafts <strong>Art</strong>s International<br />

Magazine and Surface Design Magazine.<br />

This acclaimed artist will be performing at the Matheson<br />

Performing <strong>Art</strong>s <strong>Center</strong> on Sunday, October 24th, at 7 pm.<br />

Tickets are available in advance for $16 ($22 at the door).<br />

Phone the <strong>Mendocino</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong> at 707-937-5818 to order<br />

tickets.<br />

Sha Sha will also be teaching a workshop entitled “Golden<br />

Archetype on a Stick” on Saturday, October 23rd, the day<br />

before her performance, where you can create masks to use<br />

to participate in the performance. Contact Sha Sha Higby at<br />

415 868-2409 for details regarding the workshop.<br />

For more information about Sha Sha Higby and to view a<br />

movie of one of her performances, visit her Web site at www.<br />

shashahigby.com<br />

*reprinted from www.shashahigby.com

Book Review<br />

Maguey Journey<br />

by Kathryn Rousso<br />

reviewed by Barbara Shapiro<br />

Basket maker and former <strong>Mendocino</strong> resident<br />

Kathryn Rousso has devoted much of the past ten<br />

years to research about the maguey plant found from<br />

the southern United States to northern South America.<br />

This life sustaining plant provides food and beverage,<br />

clothing, shelter and, most prominently, thread<br />

for a wide variety of utilitarian objects. Fulbright<br />

Award winner Rousso’s research culminates in Maguey<br />

Journey: Discovering Textiles in Guatemala. Predating<br />

cotton, maguey production’s long history is tied to a<br />

continued subsistence lifestyle. Textile enthusiasts will<br />

love this book as will ethno-botanists, anthropologists,<br />

and travelers to Latin America. Rousso shares her passion<br />

for the quieter Guatemalan maguey textiles often<br />

overlooked by comparison to colorful backstrap woven<br />

cotton trajes. Her approach is culturally sensitive with<br />

attention to detail born from years<br />

of experience as a textile artist.<br />

In Part One, “The Land of<br />

Maguey,” we meet the men and<br />

women who for centuries have<br />

worked this strong and versatile<br />

fiber with varying techniques in<br />

Guatemala’s distinct geographic<br />

regions. We revel in a travelogue<br />

of Rousso’s sometimes harrowing<br />

research trips across Guatemala<br />

since the 1980’s. We meet the generous<br />

maguey workers she encountered<br />

whose practices vary by community.<br />

Part Two, “The Plant to<br />

Textile Transformation,” clarifies<br />

the biology, growth, fiber extraction,<br />

dyeing, spinning and textile<br />

production of maguey in a seemingly<br />

endless variety of structures.<br />

Techniques examined include<br />

looping, knitting, ply split darning,<br />

linking, interlacing, braiding, and weaving. There are<br />

diagrams and references for further study as well as<br />

beautiful photos. Rousso explains common equipment<br />

including several loom types and the many products<br />

fashioned from maguey including ropes, cargo nets,<br />

bags, tumplines, horse and mule gear, hammocks, and<br />

even fireworks. Part Three, “The Gift of Life,” explores<br />

the economics of this most persistent Guatemalan cottage<br />

industry. In spite of dramatic changes in demographics<br />

since post civil war stability encouraged greater<br />

international trade and the incursion of plastic into<br />

traditional life, Rousso is enthusiastic about a future for<br />

maguey as a sustainable green product. Maguey Journey<br />

is a fascinating read about the staying power of this<br />

durable fiber and the people who have mastered it.<br />

Maguey Journey: Discovering Textiles in Guatemala,<br />

University of Arizona Press,<br />

2010, is available at Amazon.<br />

com and through the publisher.<br />

Kathy Rousso is the former<br />

coordinator of the Fiber <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Department at the <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>. She currently<br />

resides in Ketchikan, Alaska.<br />

Barbara Shapiro is a textile artist<br />

and educator from the Bay<br />

Area. Her weavings and baskets<br />

are profoundly influenced<br />

by traditional and historic textile<br />

traditions. She is a board<br />

member of the Textile Society<br />

of America and recently taught<br />

an indigo dyeing workshop at<br />

the <strong>Mendocino</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>.<br />

www.barbara-shapiro.com<br />

11

12<br />

Shozo Sato:<br />

Living Treasure<br />

by Michael Potts<br />

In a magical tea garden at the end of a tree tunnel<br />

in Inglenook, there lives a Japanese wizard. He is a private,<br />

gentle, courtly man, who nevertheless radiates a<br />

powerful force. He uses that force to transform people<br />

into artists.<br />

Shozo Sato describes Kamakura, where he grew<br />

up, as “a city of 100,000 people and 300 Zen temples:<br />

Kabuki actors, Nobel prize winners... a highly motivated<br />

culture.” Shozo’s father was a doctor, his mother<br />

an ardent theater-goer. Shozo was born in 1933, the<br />

year Japan left the League of Nations and began beating<br />

war drums. “When I was four, my father returned<br />

from a house call to find me dancing in a kimono of<br />

my mother’s. I started my study of traditional Japanese<br />

dance when I was six. Like other boys, I was always<br />

being asked what I wanted to become. Boys my age<br />

were expected to answer ‘pilot’ or ‘commander’ or<br />

‘soldier’ but I always said, ‘artist’. I was a problem kid,<br />

sneaking out of academic classes into other people’s<br />

art classes.<br />

“It was a blessing: from childhood, I always knew<br />

what I wanted to do.” Japanese who lived through the<br />

Occupation remember it as a harsh time, but Shozo<br />

stayed in his own room, practicing dance, painting,<br />

making drama. He attended a fine arts high school<br />

and college, taking a degree in oil painting. “My classmates<br />

always talked of going to Paris and New York to<br />

become famous artists, but they didn’t know Japanese<br />

art. I think, if you want to stand on the world stage,<br />

you must know your own native art, and the philosophy<br />

behind it, because eventually that will come out.<br />

“When I was 19, I began to wonder how to earn a<br />

living. My childhood mentor, a painting master, prohibited<br />

selling paintings, because this ‘success’ locks an<br />

artist into the style of the sold painting, and creativity<br />

is lost. This becomes a form of prostituting the soul. As<br />

an artist, you must not think of yourself as a merchant.<br />

So I offered my services to an orphanage for free. Every<br />

Saturday I taught art to orphans. In those days, the<br />

orphanages were filled with children of mixed races:<br />

Black, Brown, White, who were left in little baskets at<br />

the orphanage door. Every child has a different way of<br />

drawing, and to me their different ethnic backgrounds<br />

were obvious. Soon I was teaching art in the U.S. Naval<br />

Independent School. My talent for seeing ethnicity in<br />

paintings helped me understand that we all have different<br />

gifts. By encouraging these differences, we can<br />

help children find their creativity.”<br />

A resurgence in Japanese reverence for culture<br />

in the post-war years offered abundant opportunities<br />

for Shozo to learn new artistic disciplines. He studied<br />

Kabuki with one of the Living National Treasures,<br />

Nakamura, Kanzaburo XVII, who honored Shozo<br />

with the title Nakamura, Kanzo IV. During this time<br />

he also studied Ikebana (the art of arranging flowers)<br />

and the Tea Ceremony. He opened a small private art<br />

Photos by Larry R. Wagner

academy where he taught Sumi-E (black ink painting),<br />

Ikebana, the Tea Ceremony, and Kabuki Dance.<br />

Shozo recounts, “One day, a tall American lady, a<br />

Fulbright scholar from the University of Illinois, came<br />

to visit my academy. She wanted to learn why so many<br />

Japanese artists practice many disciplines. I told her,<br />

Simple: Japanese arts are all inter-related. Because<br />

Japan has few raw materials, the only way to survive<br />

on the international scene is to produce people with<br />

talent. After two weeks of attending classes, she asked<br />

me if I would come to Illinois if I was invited.”<br />

Shozo took the invitation to be a calling. From the<br />

mid-1960s, Professor Sato taught at the University of<br />

Illinois, Champaign-<br />

Urbana. He was<br />

often invited to<br />

other cities, universities,<br />

and museums<br />

to give lecturedemonstrations,<br />

becoming a roving<br />

ambassador for the<br />

Japanese arts. At<br />

the University of<br />

Illinois, his Kabuki<br />

Theater productions<br />

were enthusiastically<br />

received, transforming<br />

the way many<br />

midwesterners perceived their world. Appreciated for<br />

his unusual style and teaching gift, Shozo was granted<br />

permanent residency by an Act of Congress (90-S-2422<br />

sponsored by Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin).<br />

“Starting a Kabuki group in Japan is easy: you just<br />

go to the costumer and the wigmaker. In the midst of<br />

a cornfield in Illinois, you get books, learn how to sew<br />

costumes, find suitable materials, make wigs. Striving<br />

for authenticity, I learned a lot. I accepted my calling<br />

– maybe, more a matter of Karma? – to come to the<br />

United States and, being different, make use of those<br />

differences with my students, to try to open their<br />

eyes and hearts a little bit. In Japan and the U.S., this<br />

was a time of grassroots<br />

peace activity,<br />

and activists welcomed<br />

intercultural<br />

exchanges. We cannot<br />

leave peace up<br />

to governments,<br />

because industry<br />

pressures governments<br />

into wars ‘to<br />

make a buck.’”<br />

In 1967,<br />

Shozo was invited<br />

to <strong>Mendocino</strong> by<br />

Bill Zacha, whose<br />

interest in Japanese<br />

13

14<br />

art has enriched the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>. “I thought, ‘ocean,<br />

culture, just like Kamakura.’ I didn’t know it was a cold<br />

water place, and so on my first Sunday I put on my<br />

swimsuit and went to the beach. People were saying,<br />

‘look at that crazy guy.’ Ah! The <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, the ocean<br />

through the Cypress trees behind it: like Kamakura!”<br />

As his eminence grew, Professor’s Sato’s skill as a<br />

teacher increasingly called him away from Japan House,<br />

his Illinois venue, and all the travel on icy midwestern<br />

roads led him to look for a milder climate. <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

called, and by 1990 he and his wife, Alice, chose to build<br />

his <strong>Center</strong> for the Japanese <strong>Art</strong>s in Northern California,<br />

north of Fort Bragg.<br />

“There is an art to knowing a student’s needs,<br />

presenting new ideas in a way that can be understood.<br />

University students take courses because school requires<br />

them to study different cultures. Older students, coming<br />

of their own will, are seeking something: Fun? Meaning?<br />

Philosophical background? Every one: different. My lefthanded<br />

Zen monk copies Sutras, learning every stroke<br />

backwards. It is impossible. In Japan, everyone learns to<br />

write with their right hands because Japanese is a righthanded<br />

system. I challenge each student with something<br />

exotic, entertaining, so, before they know, they are seriously<br />

studying. First, catch their interest, then gradually,<br />

like training a wild horse, sprinkle sugar cubes, carrots,<br />

whatever the horse likes...”<br />

Zacha’s interest in Japan kept the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong> gazing<br />

westward, resulting in <strong>Mendocino</strong>’s sister city relationship<br />

with the town of Miasa. “I am pleased that the<br />

Miasa program carries on,” Shozo says. “The <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

can present events that open hearts to Asian sensibilities.<br />

Once our hearts open, we will maintain our quest for<br />

mastery of the art of life. It is an honor for me to have an<br />

opportunity to present this Japanese attitude to people<br />

who honestly wish to learn.<br />

“You see,” he continues, “Japan honors culture. For<br />

example, during a political campaign, people bring a nice<br />

piece of paper to a candidate and ask him to do some<br />

calligraphy. If they like what he paints, they vote for him.<br />

Calligraphy is a very revealing art and can show the quality<br />

of a person. In other disciplines, materials change,<br />

subjects differ, but the center of the self stays the same.”<br />

To share his art more widely, Shozo has produced<br />

four gorgeous books, two authoritative works for adults,<br />

Sumi-E: The <strong>Art</strong> Of Japanese Ink Painting and Ikebana:<br />

The <strong>Art</strong> Of Arranging Flowers, and two for children,<br />

Tea Ceremony and Ikebana: Asian <strong>Art</strong>s And Crafts For<br />

Creative Kids, all published by Tuttle.<br />

As befits a wizard, Professor Sato circulates, ageless,<br />

graceful, and wise, among his students in the workroom<br />

of his Inglenook academy, guiding a hesitant hand, whispering<br />

encouragement. A local physician looks up from<br />

a finished character. “This is harder than heart surgery,”<br />

he confesses. The wizard smiles.

<strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

Sandpiper<br />

Affordable Jewelry<br />

since 1987<br />

Featuring Jewelry<br />

by Tabra<br />

“Where The Locals Shop”<br />

937-3102<br />

45280 Main Street,<br />

<strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

Open Daily<br />

At west end of Main St.<br />

Roxanne Vold, Proprietor<br />

OCEANFRONT INN<br />

& COTTAGES<br />

Just steps to the beach and<br />

a stroll to fine restaurants, galleries<br />

and the <strong>Mendocino</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Center</strong>.<br />

ocean views • decks • fireplaces<br />

An enchanting refuge for<br />

rest and renewal...<br />

On Main Street at Evergreen<br />

<strong>Mendocino</strong> Village<br />

800 780-7905 • 707 937-5150<br />

www.oceanfrontmagic.com<br />

Studio<br />

& Gallery<br />

M E N D O C I N O<br />

gems<br />

Custom design & repair<br />

10483 Lansing St. • <strong>Mendocino</strong><br />

937-0299<br />

Kaleidoscopes ◆ <strong>Art</strong> Glass ◆ Mirrors ◆ Jewelry<br />

4 5 0 5 0 M a in S t r e e t ■ M e n d o c in o , C a l if o r ni a<br />

E n t r a n c e o n A l b i o n S t r e e t ■ O p e n d a i l y<br />

www.reflections-k aleidoscopes.com ■ 937- 0173<br />

15