the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

272 4 : <strong>africa</strong>n art and <strong>the</strong> influences <strong>of</strong> foreign trade<br />

101<br />

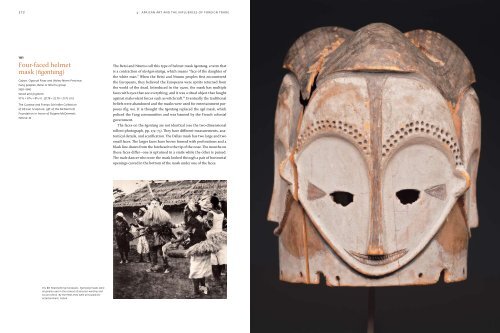

Four‑faced helmet<br />

mask (ñgontang)<br />

Gabon, Ogooué River and Woleu-Ntem Province,<br />

Fang peoples, Betsi or Ntumu group<br />

1920–1940<br />

Wood and pigment<br />

1015/! 6 × 815/! 6 × 89/! 6 in. (27.78 × 22.70 × 21.75 cm)<br />

The Gustave and Franyo Schindler Collection<br />

<strong>of</strong> African Sculpture, gift <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> McDermott<br />

Foundation in honor <strong>of</strong> Eugene McDermott,<br />

1974.SC.33<br />

fig 60 Representing Europeans, ñgontang masks were<br />

originally used in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> ancestor worship and<br />

social control. By <strong>the</strong> 1960s <strong>the</strong>y were principally for<br />

entertainment. Gabon.<br />

The Betsi and Ntumu call this type <strong>of</strong> helmet mask ñgontang, a term that<br />

is a contraction <strong>of</strong> nlo ñgon ntañga, which means “face <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> daughter <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> white man.” When <strong>the</strong> Betsi and Ntumu peoples first encountered<br />

<strong>the</strong> Europeans, <strong>the</strong>y believed <strong>the</strong> Europeans were spirits returned from<br />

<strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dead. Introduced in <strong>the</strong> 1920s, <strong>the</strong> mask has multiple<br />

faces with eyes that see everything, and it was a ritual object that fought<br />

against malevolent forces such as witchcraft.21 Eventually <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

beliefs were abandoned and <strong>the</strong> masks were used for entertainment pur‑<br />

poses (fig. 60). It is thought <strong>the</strong> ñgontang replaced <strong>the</strong> ngil mask, which<br />

policed <strong>the</strong> Fang communities and was banned by <strong>the</strong> French colonial<br />

government.<br />

The faces on <strong>the</strong> ñgontang are not identical (see <strong>the</strong> two‑dimensional<br />

rollout photograph, pp. 274–75). They have different measurements, ana‑<br />

tomical details, and scarification. The <strong>Dallas</strong> mask has two large and two<br />

small faces. The larger faces have brows formed with perforations and a<br />

black line drawn from <strong>the</strong> forehead to <strong>the</strong> tip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nose. The mouths on<br />

<strong>the</strong>se faces differ—one is upturned in a smile while <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is pursed.<br />

The male dancer who wore <strong>the</strong> mask looked through a pair <strong>of</strong> horizontal<br />

openings carved in <strong>the</strong> bottom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mask under one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> faces.