the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

44 1 : icons and symbols <strong>of</strong> leadership and status<br />

3<br />

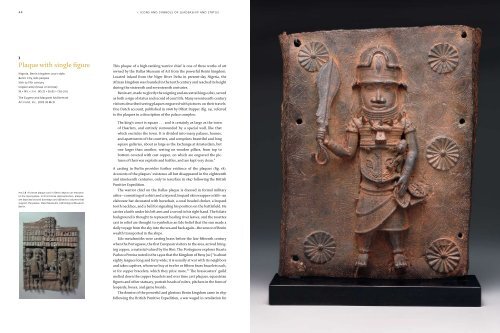

Plaque with single figure<br />

Nigeria, Benin kingdom court style,<br />

Benin City, Edo peoples<br />

16th to 17th century<br />

Copper alloy (brass or bronze)<br />

18 × 14½ × 3 in. (45.72 × 36.83 × 7.62 cm)<br />

The Eugene and Margaret McDermott<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Fund, Inc., 2005.38.McD<br />

fig 18 A bronze plaque cast in Benin depicts an entrance<br />

to <strong>the</strong> royal palace. In this bronze repre sentation, plaques<br />

are depicted around doorways and affixed to columns that<br />

support <strong>the</strong> palace. State <strong>Museum</strong>s, Ethnological <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

Berlin.<br />

This plaque <strong>of</strong> a high-ranking warrior chief is one <strong>of</strong> three works <strong>of</strong> art<br />

owned by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dallas</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> from <strong>the</strong> powerful Benin kingdom.<br />

Located inland from <strong>the</strong> Niger River Delta in present-day Nigeria, <strong>the</strong><br />

African kingdom was founded in <strong>the</strong> tenth century and reached its height<br />

during <strong>the</strong> sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.<br />

Benin art, made to glorify <strong>the</strong> reigning and ancestral kings (oba), served<br />

as both a sign <strong>of</strong> status and record <strong>of</strong> court life. Many seventeenth-century<br />

visitors described seeing plaques engraved with pictures on <strong>the</strong>ir travels.<br />

One Dutch account, published in 1668 by Olfert Dapper (fig. 19), referred<br />

to <strong>the</strong> plaques in a description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palace complex:<br />

The king’s court is square . . . and is certainly as large as <strong>the</strong> town<br />

<strong>of</strong> Haarlem, and entirely surrounded by a special wall, like that<br />

which encircles <strong>the</strong> town. It is divided into many palaces, houses,<br />

and apartments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long<br />

square galleries, about as large as <strong>the</strong> Exchange at Amsterdam, but<br />

one larger than ano<strong>the</strong>r, resting on wooden pillars, from top to<br />

bottom covered with cast copper, on which are engraved <strong>the</strong> pictures<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir war exploits and battles, and are kept very clean.5<br />

A casting in Berlin provides fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plaques (fig. 18).<br />

Accounts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plaques’ existence all but disappeared in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth<br />

and nineteenth centuries, only to resurface in 1897 following <strong>the</strong> British<br />

Punitive Expedition.<br />

The warrior chief on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dallas</strong> plaque is dressed in formal military<br />

attire—consisting <strong>of</strong> a shirt and a layered, leopard skin wrapper or kilt—an<br />

elaborate hat decorated with horsehair, a coral beaded choker, a leopard<br />

tooth necklace, and a bell for signaling his position on <strong>the</strong> battlefield. He<br />

carries a knife under his left arm and a sword in his right hand. The foliate<br />

background is thought to represent healing river leaves, and <strong>the</strong> rosettes<br />

cast in relief are thought to symbolize an Edo belief that <strong>the</strong> sun made a<br />

daily voyage from <strong>the</strong> sky into <strong>the</strong> sea and back again—<strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> Benin<br />

wealth transported in <strong>the</strong> ships.<br />

Edo metalsmiths were casting brass before <strong>the</strong> late fifteenth century<br />

when <strong>the</strong> Portuguese, <strong>the</strong> first European visitors to <strong>the</strong> area, arrived bringing<br />

copper, a material valued by <strong>the</strong> Bini. The Portuguese explorer Duarte<br />

Pacheco Pereira noted in <strong>the</strong> 1490s that <strong>the</strong> Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Beny [sic] “is about<br />

eighty leagues long and forty wide; it is usually at war with its neighbors<br />

and takes captives, whom we buy at twelve or fifteen brass bracelets each,<br />

or for copper bracelets, which <strong>the</strong>y prize more.”6 The brasscasters’ guild<br />

melted down <strong>the</strong> copper bracelets and over time cast plaques, equestrian<br />

figures and o<strong>the</strong>r statuary, portrait heads <strong>of</strong> rulers, pitchers in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong><br />

leopards, boxes, and game boards.<br />

The demise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> powerful and glorious Benin kingdom came in 1897<br />

following <strong>the</strong> British Punitive Expedition, a war waged in retaliation for