the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

56 1 : icons and symbols <strong>of</strong> leadership and status<br />

6<br />

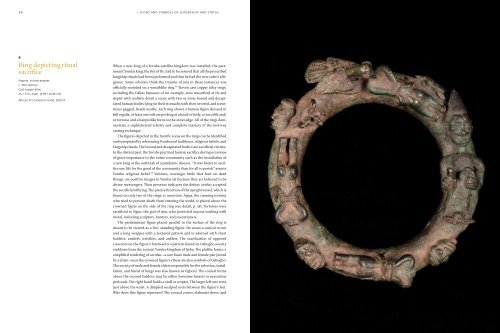

Ring depicting ritual<br />

sacrifice<br />

Nigeria, Yoruba peoples<br />

c. 18th century<br />

Cast copper alloy<br />

2¾ × 9 in. diam. (6.99 × 22.86 cm)<br />

African <strong>Art</strong> Collection Fund, 2005.14<br />

When a new king <strong>of</strong> a Yoruba satellite kingdom was installed, <strong>the</strong> paramount<br />

Yoruba king, <strong>the</strong> Oni <strong>of</strong> Ife, had to be assured that all <strong>the</strong> prescribed<br />

kingship rituals had been performed and that he had <strong>the</strong> new ruler’s allegiance.<br />

Some scholars think <strong>the</strong> transfer <strong>of</strong> rule in <strong>the</strong>se instances was<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficially recorded on a wreathlike ring.19 Eleven cast copper alloy rings,<br />

including <strong>the</strong> <strong>Dallas</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> example, were unear<strong>the</strong>d at Ife and<br />

depict with realistic detail a scene with two or more bound and decapitated<br />

human bodies lying on <strong>the</strong>ir stomachs with <strong>the</strong>ir severed, and sometimes<br />

gagged, heads nearby. Each ring shows a human figure dressed in<br />

full regalia, at least one vulture pecking at a head or body, a crocodile and/<br />

or tortoise and a hairpinlike form on <strong>the</strong> outer edge. All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rings demonstrate<br />

a sophisticated artistry and complete mastery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lost-wax<br />

casting technique.<br />

The figures depicted in <strong>the</strong> horrific scene on <strong>the</strong> rings can be identified<br />

and interpreted by referencing Yoruba oral traditions, religious beliefs, and<br />

kingship rituals. The bound and decapitated bodies are sacrificial victims.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> distant past, <strong>the</strong> Yoruba practiced human sacrifice during occasions<br />

<strong>of</strong> grave importance to <strong>the</strong> entire community such as <strong>the</strong> installation <strong>of</strong><br />

a new king or <strong>the</strong> outbreak <strong>of</strong> a pandemic disease. “It was better to sacrifice<br />

one life for <strong>the</strong> good <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community than for all to perish” asserts<br />

Yoruba religious belief.20 Vultures, scavenger birds that feed on dead<br />

things, are positive images in Yoruba art because <strong>the</strong>y are believed to be<br />

divine messengers. Their presence indicates <strong>the</strong> deities (orisha) accepted<br />

<strong>the</strong> sacrificial <strong>of</strong>fering. The precise function <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> upright vessel, which is<br />

found on only two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rings, is uncertain. Ajapa, <strong>the</strong> cunning tortoise<br />

who tried to prevent death from entering <strong>the</strong> world, is placed above <strong>the</strong><br />

crowned figure on <strong>the</strong> side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ring (see detail, p. 58). Tortoises were<br />

sacrificed to Ogun, <strong>the</strong> god <strong>of</strong> iron, who protected anyone working with<br />

metal, including sculptors, hunters, and executioners.<br />

The predominant figure placed parallel to <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ring is<br />

meant to be viewed as a live, standing figure. He wears a conical crown<br />

and a long wrapper with a textured pattern and is adorned with chest<br />

baldrics, armlets, wristlets, and anklets. The scarification <strong>of</strong> opposed<br />

crescents on <strong>the</strong> figure’s forehead is a pattern found on Oshugbo society<br />

emblems from <strong>the</strong> ancient Yoruba kingdom <strong>of</strong> Ijebu. The pinlike forms, a<br />

simplified rendering <strong>of</strong> an edan—a cast brass male and female pair joined<br />

by a chain—near <strong>the</strong> crowned figure’s elbow are also symbols <strong>of</strong> Oshugbo.<br />

The society <strong>of</strong> male and female elders responsible for <strong>the</strong> selection, installation,<br />

and burial <strong>of</strong> kings was also known as Ogboni. The conical forms<br />

above <strong>the</strong> crossed baldrics may be ei<strong>the</strong>r feminine breasts or masculine<br />

pectorals. The right hand holds a staff or scepter. The larger left one rests<br />

just above <strong>the</strong> waist. A dimpled seedpod rests between <strong>the</strong> figure’s feet.<br />

Who does this figure represent? The conical crown, elaborate dress, and