the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

the arts of africa - Dallas Museum of Art

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

30 <strong>africa</strong>n art in context <strong>africa</strong>n art in context 31<br />

Mpumalanga province7 (fig. 14), and a carved wood animal head from a site<br />

east <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cuanza River in <strong>the</strong> Liavela area <strong>of</strong> central Angola8 (fig. 15).<br />

The oldest works <strong>of</strong> art in <strong>the</strong> DMA’s collections are a terracotta male<br />

figure from <strong>the</strong> modern state <strong>of</strong> Sokoto in northwestern Nigeria that dates<br />

from between 200 BC and AD 200 and a standing female figure, from a pre-<br />

Dogon culture in Mali, that is conservatively dated from <strong>the</strong> eleventh to<br />

thirteenth century.9 These are followed by cast copper alloy figures and a<br />

carved ivory waist pendant from <strong>the</strong> Benin kingdom that date from <strong>the</strong><br />

sixteenth to eighteenth century. All are made <strong>of</strong> du rable materials or, in<br />

<strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pre-Dogon figure, survived owing to a combination <strong>of</strong> a<br />

durable material (hardwood) and <strong>the</strong> dry climate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> western Sudan.<br />

As with most African art collections, <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> works at <strong>the</strong> DMA<br />

were made <strong>of</strong> wood or o<strong>the</strong>r organic materials during <strong>the</strong> late nineteenth<br />

to mid-twentieth century. Had <strong>the</strong>y remained in Africa <strong>the</strong>se objects would<br />

have been destroyed by <strong>the</strong> moist climate and wood-eating insects inhabiting<br />

<strong>the</strong> rain forests. The prevailing opinion maintains most extant wooden<br />

sculptures are replacements; that is, <strong>the</strong>y were in use for not more than a<br />

generation or two before <strong>the</strong>y were brought out <strong>of</strong> Africa. It was customary<br />

to replace ritual objects with new ones.<br />

The history <strong>of</strong> African art, like <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Africa itself, remains a work<br />

in progress. The reconstruction <strong>of</strong> Africa’s art history, especially south <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Sahara where conventional systems <strong>of</strong> inscription are absent,10 depends<br />

upon indigenous oral traditions and early European and Arabic documents<br />

from travelers, missionaries, merchants, and colonial <strong>of</strong>ficers. Sources <strong>of</strong><br />

information also include linguistics, archaeology, and scientific dating<br />

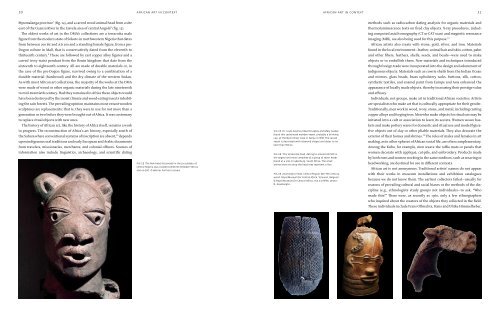

fig 12 The Nok head discovered in <strong>the</strong> Jos plateau <strong>of</strong><br />

central Nigeria was created sometime between 500 bc<br />

and ad 200. © Werner Forman / corbis.<br />

fig 13 Dr. Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey and Mary Leakey<br />

found this carbonized wooden vessel, probably a drinking<br />

cup, at <strong>the</strong> Njoro River Cave in Kenya in 1938. The carved<br />

vessel is decorated with diamond shapes and dates to no<br />

later than 850 bc.<br />

fig 14 This terracotta head, dating to around ad 500 is<br />

<strong>the</strong> largest and most complete <strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> seven heads<br />

found at a site in Lydenburg, South Africa. The small<br />

animal that sits atop <strong>the</strong> head may represent a lion.<br />

fig 15 Zoomorphic head, Central Angola, 8th–9th century,<br />

wood. Royal <strong>Museum</strong> for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium.<br />

© Royal <strong>Museum</strong> for Central Africa, pre.0.0.14796; photo:<br />

R. Asselberghs.<br />

methods such as radiocarbon dating analysis for organic materials and<br />

<strong>the</strong>rmoluminescence tests on fired clay objects. X-ray procedures, including<br />

computed axial tomography (CT or CAT scan) and magnetic resonance<br />

imaging (MRI), are also being used for this purpose.11<br />

African artists also create with stone, gold, silver, and iron. Materials<br />

found in <strong>the</strong> local environment—lea<strong>the</strong>r, animal hair and skin, cotton, palm<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r fibers, fea<strong>the</strong>rs, shells, seeds, and beads—were used to make<br />

objects or to embellish <strong>the</strong>m. New materials and techniques introduced<br />

through foreign trade were incorporated into <strong>the</strong> design and adornment <strong>of</strong><br />

indigenous objects. Materials such as cowrie shells from <strong>the</strong> Indian Ocean<br />

and mirrors, glass beads, brass upholstery tacks, buttons, silk, cotton,<br />

syn<strong>the</strong>tic textiles, and enamel paint from Europe and Asia enhanced <strong>the</strong><br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> locally made objects, <strong>the</strong>reby increasing <strong>the</strong>ir prestige value<br />

and efficacy.<br />

Individuals, not groups, make art in traditional African societies. <strong>Art</strong>ists<br />

are specialists who make art that is culturally appropriate for <strong>the</strong>ir gender.<br />

Traditionally, men work in wood, ivory, stone, and metal, including casting<br />

copper alloys and forging iron. Men who make objects for ritual use may be<br />

initiated into a cult or association to learn its secrets. Women weave baskets<br />

and make pottery wares for domestic and ritual use and model figurative<br />

objects out <strong>of</strong> clay or o<strong>the</strong>r pliable materials. They also decorate <strong>the</strong><br />

exterior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir homes and shrines.12 The roles <strong>of</strong> males and females in art<br />

making, as in o<strong>the</strong>r spheres <strong>of</strong> African social life, are <strong>of</strong>ten complementary.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Kuba, for ex ample, men weave <strong>the</strong> raffia mats or panels that<br />

women decorate with appliqué, cut-pile, and embroidery. Products made<br />

by both men and women working in <strong>the</strong> same medium, such as weaving or<br />

beadworking, are destined for use in different contexts.<br />

African art is not anonymous. Traditional artists’ names do not appear<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir works in museum installations and exhibition catalogues<br />

because we do not know <strong>the</strong>m. The earliest collectors failed—usually for<br />

reasons <strong>of</strong> prevailing cultural and racial biases or <strong>the</strong> methods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discipline<br />

(e.g., ethnologists study groups not individuals)—to ask, “Who<br />

made this?” There were, as recently as 1960, only a few ethnographers<br />

who inquired about <strong>the</strong> creators <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> objects <strong>the</strong>y collected in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

These individuals include Frans Olbrechts, Hans and Ulrike Himmelheber,