Limpopo Leader - Spring 2005 - University of Limpopo

Limpopo Leader - Spring 2005 - University of Limpopo

Limpopo Leader - Spring 2005 - University of Limpopo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

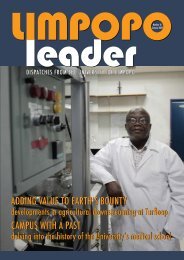

Dr David Norris<br />

tTO WATCH DR DAVID NORRIS WORKING WITH HIS<br />

CHICKENS IS TO CATCH SIGHT OF A SCIENTIFIC<br />

INTEREST BORDERING ON OBSESSION. He laughs<br />

a lot. He’s an easy man to be around. Yet his focus is<br />

very firmly on his chickens.<br />

‘All these are indigenous African chickens,’ he<br />

says, indicating the scruffy scratching poultry in<br />

several pens on the School <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and<br />

Environmental Science’s experimental farm not far<br />

from the Turfloop campus <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>.<br />

‘Those on that side are naked-necked chickens, and<br />

they’re found all over South Africa. These here – the<br />

black and white speckled ones – are called Venda<br />

chickens.’<br />

Nothing much to look at, these indigenous chickens.<br />

A few <strong>of</strong> the roosters have most <strong>of</strong> their tail feathers<br />

missing, and the naked-necked bunch seems vaguely<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> vultures. Yet they have one huge<br />

strength. They’re adapted to local conditions. In other<br />

words, they have developed physiological and<br />

anatomical systems that make any exotic breeds look<br />

positively puny.<br />

‘The imported breeds are especially engineered for<br />

high egg or meat production,’ explains Norris, ‘but in<br />

Southern African conditions they need high inputs –<br />

inoculations, special feeds, and so on – and mortality<br />

rates are high. In other words, they’re expensive -<br />

much too expensive for local conditions. On the other<br />

hand, the indigenous chickens represent a huge<br />

genetic resource. If we’re serious about poverty<br />

alleviation, let’s work with the local stock. That’s the<br />

thinking behind my research.’<br />

Although an estimated 75% <strong>of</strong> South African chicken<br />

production is from local breeds, most scientists are<br />

marginalising the indigenous strains. But not Norris,<br />

who’s a quantitative geneticist at Turfloop. The initial<br />

phase <strong>of</strong> his research was to do a ‘phenotypic characterisation’<br />

study that examined such elements as size,<br />

growth rate, feeding requirements, egg size and output.<br />

‘Because <strong>of</strong> the wholesale neglect <strong>of</strong> the past,’ says<br />

Norris, ‘we know nothing <strong>of</strong> the respective breeds. So<br />

it’s been important to carry out genetic characterisation<br />

that begins to match the external characteristics<br />

with the genetic types. It’s important for another<br />

reason as well. Conservation. We are identifying<br />

and conserving African breeds that have been around<br />

for a very long time but that have almost become<br />

extinct.’<br />

Norris was born and grew up in Botswana, doing<br />

his undergraduate studies at the university in<br />

Gaberone. He then moved to the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Reading (in the United Kingdom) and Michigan State<br />

<strong>University</strong> (USA) where he completed his master’s and<br />

PhD degrees respectively. His doctoral thesis dealt<br />

with ‘the dominance effects in genetic variation’.<br />

Norris has also done special courses in quantitative<br />

genetics in the United States (Michigan) and Canada,<br />

and he taught for a period <strong>of</strong> two years at Austin Peay<br />

State <strong>University</strong> in Tennessee. ‘I really loved the Deep<br />

South,’ he recalls. ‘It was so much warmer than<br />

Michigan or Canada – much more suitable for<br />

someone from Southern Africa.’<br />

Norris returned to Botswana in 2000 and made<br />

the move to Turfloop a year later. Asked why, he<br />

replies: ‘I loved the opportunity to combine teaching<br />

and research that Turfloop <strong>of</strong>fered.’<br />

And the marginalised indigenous chickens all over<br />

Southern Africa have benefited. Norris has established<br />

linkages with the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Venda, as well as tertiary<br />

institutions in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.<br />

Relationships are also in the pipeline with Swaziland<br />

and Botswana. ‘These links enable us to exchange<br />

information and research findings on indigenous poultry.<br />

I have also made personal visits. I’m now looking for<br />

funding to more formally establish the international<br />

interactions to cover the whole <strong>of</strong> the SADC region.<br />

This will enrich our understanding <strong>of</strong> a significant<br />

regional resource and improve its utility in our fight<br />

against poverty and under-development.’<br />

Next step in Norris’s indigenous chicken research<br />

is a programme <strong>of</strong> selective breeding to improve the<br />

productivity <strong>of</strong> the chickens without damaging their<br />

adaptability to the environment. At the same time, a<br />

genuine African livestock resource will be conserved<br />

and used as a realistic alternative to much more<br />

vulnerable and expensive breeds imported from<br />

America and Europe.<br />

P A G E 1 5