Global Burden of Armed Violence - The Geneva Declaration on ...

Global Burden of Armed Violence - The Geneva Declaration on ...

Global Burden of Armed Violence - The Geneva Declaration on ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

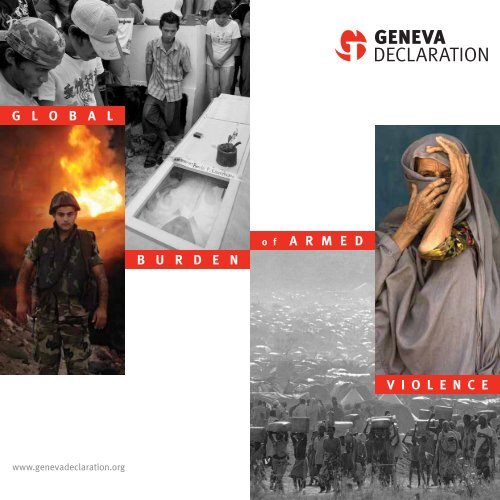

G L O B A L<br />

www.genevadeclarati<strong>on</strong>.org<br />

B U R D E N<br />

o f A R M E D<br />

GENEVA<br />

DECLARATION<br />

V I O L E N C E

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report is the first compre-<br />

hensive assessment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human tragedy resulting<br />

from violence around the world. More than 740,000 people<br />

die each year as a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>flict-related and homicidal violence—<br />

a figure that should capture the attenti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers and<br />

activists worldwide.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report brings into focus the wide-ranging costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war and<br />

crime <strong>on</strong> development and provides a solid evidence base to shape<br />

effective policy, programming, and advocacy to prevent and reduce<br />

armed violence. Drawing from diverse sources and approaches,<br />

chapters focus <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>flict-related, post-c<strong>on</strong>flict, and criminal armed<br />

violence, and <strong>on</strong> the enormous ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report also highlights some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the less visible forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence, including sexual and gender-based violence, extrajudicial<br />

killings, kidnappings, and forced disappearances.<br />

Photos<br />

Top left: Mourners at the funeral <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a former gang member in Davao, the Philippines.<br />

© Lucian Read/Small Arms Survey<br />

Centre left: A Lebanese soldier by a burning vehicle.<br />

© Jeroen Oerlemans/Panos Pictures<br />

Bottom right: Rwandan refugees at a camp in Tanzania, 1994.<br />

© Karsten Thielker/AP Photo<br />

Centre right: An Afghan woman photographed in her village near Kandahar, 2002.<br />

© Danielle Bernier/DGPA/J5PA Combat Camera<br />

www.genevadeclarati<strong>on</strong>.org<br />

ISBN 978-2-8288-0101-4<br />

GENEVA<br />

DECLARATION 9 782828 801014

G L O B A L<br />

www.genevadeclarati<strong>on</strong>.org<br />

B U R D E N<br />

o f A R M E D<br />

GENEVA<br />

DECLARATION<br />

V I O L E N C E

ii<br />

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

Copyright<br />

Published in Switzerland by the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Secretariat<br />

© <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Secretariat, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2008<br />

First published in September 2008<br />

All rights reserved. No part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this publicati<strong>on</strong> may<br />

be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or<br />

transmitted, in any form or by any means, without<br />

the prior permissi<strong>on</strong> in writing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Secretariat, or as expressly permitted<br />

by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate<br />

reprographics rights organizati<strong>on</strong>. Enquiries<br />

c<strong>on</strong>cerning reproducti<strong>on</strong> outside the scope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the above should be sent to the Publicati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Manager at the address below.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Secretariat<br />

c/o Small Arms Survey<br />

47 Avenue Blanc<br />

1202 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Switzerland<br />

Copy-edited by Michael James and Alex Potter<br />

Photo research by Alessandra Allen<br />

Cartography by Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix<br />

Pro<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>read by D<strong>on</strong>ald Strachan<br />

Design and layout by Richard J<strong>on</strong>es, Exile: Design<br />

& Editorial Services (rick@studioexile.com).<br />

Typeset in Meta.<br />

Printed by Paul Green Printing in L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>,<br />

United Kingdom<br />

ISBN 978-2-8288-0101-4

Foreword<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence affects all societies to<br />

different degrees, whether they are at war,<br />

in a post-c<strong>on</strong>flict situati<strong>on</strong>, or suffering<br />

from everyday forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> criminal or political vio-<br />

lence. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence stunts human, social, and<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic development and erodes the social<br />

capital <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> communities.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> evidence assembled in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report, written by a team <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ex-<br />

perts coordinated by the Small Arms Survey for<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> and<br />

Development, provides an overview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the inci-<br />

dence, severity, and distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different types<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence—in both c<strong>on</strong>flict and n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

situati<strong>on</strong>s, from both large and small-scale violence,<br />

in criminally and politically motivated c<strong>on</strong>texts.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report is an important step towards a better<br />

understanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>—and more effective resp<strong>on</strong>ses<br />

to—the negative impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> human toll <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence across various<br />

c<strong>on</strong>texts is severe. In the recent past, at least<br />

740,000 people have died directly or indirectly<br />

each year from armed violence. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence<br />

also has a ripple effect throughout society, cre-<br />

ating a climate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fear, distorting investment,<br />

disrupting markets, and closing schools, clinics,<br />

and roads.<br />

This report also highlights the tremendous eco-<br />

nomic impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> lost<br />

productivity from n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict or criminal violence<br />

al<strong>on</strong>e is about USD 95 billi<strong>on</strong> and may reach as<br />

high as USD 163 billi<strong>on</strong> per year. War-related vio-<br />

lence decreases the annual growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an average<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omy by around two per cent for many years.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>se human and ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs make armed<br />

violence a development issue and explain why<br />

the development community is increasingly moti-<br />

vated to promote its preventi<strong>on</strong> and reducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Together with members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the core group <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> and<br />

Development, signed <strong>on</strong> 7 June 2006 in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g>,<br />

Switzerland recognizes that effective preventi<strong>on</strong><br />

and reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence requires str<strong>on</strong>g<br />

political commitment to enhance nati<strong>on</strong>al and<br />

local data collecti<strong>on</strong>, develop evidence-based<br />

programmes, invest in pers<strong>on</strong>nel, and learn from<br />

good practice.<br />

In moving in this directi<strong>on</strong> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

calls <strong>on</strong> all signatories to strengthen efforts to<br />

integrate strategies for armed violence reducti<strong>on</strong><br />

and c<strong>on</strong>flict preventi<strong>on</strong> into nati<strong>on</strong>al, regi<strong>on</strong>al, and<br />

multilateral development plans and programmes.<br />

Such instruments commit countries to make good<br />

<strong>on</strong> their promises and to back these commitments<br />

with adequate resources and leadership.<br />

Endorsed by more than 90 states, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

argues that ‘living free from the threat <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence is a basic human need’ and sets out to<br />

make ‘measurable reducti<strong>on</strong>s in the global bur-<br />

den <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence’ by 2015. Signatories to<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>—including the Swiss<br />

C<strong>on</strong>federati<strong>on</strong>—have accepted the resp<strong>on</strong>sibility<br />

iii<br />

FORE WO R D<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

iv to make a serious and sustained effort to improving<br />

the safety and security <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> people and communities<br />

through armed violence preventi<strong>on</strong> and<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> initiatives.<br />

Achieving this goal will not be easy, but by working<br />

together as governments, local authorities,<br />

and civil society partners, we can reduce the global<br />

burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report provides important signposts<br />

that can help decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers and researchers<br />

move in the right directi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

—Micheline Calmy-Rey<br />

Head <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Swiss Federal Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Foreign Affairs

C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1<br />

Dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2<br />

Preventing and reducing armed violence ................................................................................................................................................ 6<br />

Chapter One Direct C<strong>on</strong>flict Death ..................................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

A short history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths ................................................................................................................ 10<br />

Measuring the global burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths .................................................................................................... 13<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> risk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dying in armed c<strong>on</strong>flict .............................................................................................................................................................. 26<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 28<br />

Chapter Two <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Many Victims <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> War: Indirect C<strong>on</strong>flict Deaths .................................................. 31<br />

What is excess mortality? .................................................................................................................................................................................... 33<br />

Challenges to collecting and using data <strong>on</strong> indirect deaths ............................................................................................... 34<br />

Methods for quantifying indirect c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths ......................................................................................................................... 36<br />

Direct versus indirect deaths in recent c<strong>on</strong>flicts ........................................................................................................................... 39<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 42<br />

Chapter Three <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> After War:<br />

Categories, Causes, and C<strong>on</strong>sequences .................................................................................................................. 49<br />

Disaggregating post-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence ................................................................................................................................... 50<br />

Risk factors facing post-c<strong>on</strong>flict societies ........................................................................................................................................... 58<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>: promoting security after c<strong>on</strong>flict .................................................................................................................................. 63<br />

Chapter Four Lethal Encounters: N<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> ...................................................... 67<br />

Defining and measuring violent deaths ................................................................................................................................................. 68<br />

Estimating global homicide levels ............................................................................................................................................................... 71<br />

Behind the numbers: trends and distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violent deaths ..................................................................................... 75<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence and the criminal justice system ........................................................................................................................... 82<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>: knowledge gaps and policy implicati<strong>on</strong>s ............................................................................................................. 85<br />

v<br />

CO N T E N T S<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

vi Chapter Five What’s in a Number?<br />

Estimating the Ec<strong>on</strong>omic Costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> ............................................................................... 89<br />

Approaches to costing armed violence ................................................................................................................................................... 91<br />

Costing armed violence in a sample <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> countries ......................................................................................................................... 97<br />

Estimating the global ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence ................................................................. 99<br />

Positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence? ........................................................................................................................................................ 102<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 105<br />

Chapter Six <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> Against Women ............................................................................................................ 109<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> gender dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence ....................................................................................................................................... 110<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> against women in c<strong>on</strong>flict settings ................................................................................................................................... 112<br />

N<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict violence against women .................................................................................................................................................... 115<br />

Intimate partner violence ................................................................................................................................................................................... 117<br />

Sexual violence .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 118<br />

H<strong>on</strong>our killings ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 120<br />

Dowry-related violence ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 121<br />

Acid attacks ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 121<br />

Female infanticide and sex-selective aborti<strong>on</strong> ............................................................................................................................ 122<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 123<br />

Chapter Seven Other Forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g>:<br />

Making the Invisible Visible ..................................................................................................................................................... 125<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> groups and gangs ................................................................................................................................................................................. 126<br />

Extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and kidnapping ..................................................................................................... 130<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence and aid workers ................................................................................................................................................................ 138<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 139<br />

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 141<br />

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Illustrati<strong>on</strong>s ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 157<br />

Note to reader: Cross-references to other chapters are indicated in capital letters in parentheses.<br />

For example, ‘<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> battle deaths estimated in the preceding chapter for the DRC in the period<br />

2004–07 is about 9,300 (DIRECT CONFLICT DEATH).’

About the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

and Development, endorsed by more than<br />

90 states, commits signatories to supporting<br />

initiatives to measure the human, social, and<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence, to assess risks<br />

and vulnerabilities, to evaluate the effectiveness<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence reducti<strong>on</strong> programmes, and to<br />

disseminate knowledge <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> best practices. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> calls up<strong>on</strong> states to achieve measurable<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong>s in the global burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence and tangible improvements in human<br />

security by 2015. Core group members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> include Brazil, Guatemala,<br />

Finland, Ind<strong>on</strong>esia, Kenya, Morocco, the Nether-<br />

lands, Norway, the Philippines, Spain, Switzer-<br />

land, Thailand, and the United Kingdom with<br />

support from the United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Development<br />

Programme (UNDP).<br />

For more informati<strong>on</strong> about the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> Declara-<br />

ti<strong>on</strong>, related activities, and publicati<strong>on</strong>s, please<br />

visit www.genevadeclarati<strong>on</strong>.org.<br />

vii<br />

A B O U T T H E GENE VA DECL A R AT I O N<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

viii<br />

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

More than 30 specialists from a dozen<br />

research institutes around the world<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributed to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report (report, hereafter), making<br />

it a truly collective undertaking. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> Secretariat<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

and Development was resp<strong>on</strong>sible for c<strong>on</strong>ceiving,<br />

researching, commissi<strong>on</strong>ing, and editing the<br />

report. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary editors <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the report are Keith<br />

Krause, Robert Muggah, and Achim Wennmann,<br />

all with the Small Arms Survey. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>y were sup-<br />

ported by Katherine Aguirre Tobón, Jasna Lazarevic,<br />

and Il<strong>on</strong>a Szabó de Carvalho.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report reflects the c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a wide<br />

range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> instituti<strong>on</strong>al partners. Beginning in 2007,<br />

a series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sultati<strong>on</strong>s and workshops were<br />

held in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> to identify key indicators <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence, knowledge gaps, and methodological<br />

approaches. Important input was provided by<br />

Andrew Mack, Peter Batchelor, <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>odore Leggett,<br />

Steven Malby, Irene Pavesi, Jennifer Milliken,<br />

and David Taglani. Critical feedback was also<br />

provided by Jean-François Cuénod, Paul Eavis,<br />

and David Atwood, as well as from core group<br />

members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. Preliminary<br />

outputs were presented by the editors during the<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>al summits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> for<br />

Latin America in Guatemala, for Africa in Kenya,<br />

and for the Asia–Pacific regi<strong>on</strong> in Thailand. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

editors are grateful for the valuable feedback<br />

gathered <strong>on</strong> these occasi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Tania Inowlocki, the Small Arms Survey’s publi-<br />

cati<strong>on</strong>s manager, coordinated the producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Katherine<br />

Aguirre Tobón, Sarah Hoban, Jasna Lazarevic,<br />

and Tanya Rodriguez fact-checked the report;<br />

Alex Potter and Michael James served as copy-<br />

editors; Jillie Luff designed the maps; Alessandra<br />

Allen assisted with photo research; Richard J<strong>on</strong>es<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ceived <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the design and provided the layout;<br />

and D<strong>on</strong>ald Strachan pro<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>read the book. Carole<br />

Touraine managed the finances for the project,<br />

and other staff <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Small Arms Survey provided<br />

various forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> support.<br />

While the report represents a collective effort, the<br />

editors wish to recognize the following experts<br />

and instituti<strong>on</strong>s. We apologize to any<strong>on</strong>e who may<br />

have inadvertently been omitted.<br />

Direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths<br />

Much has been written <strong>on</strong> the extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct<br />

c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths, though uncertainty about its<br />

overall magnitude remains. Jorge Restrepo and<br />

Katherine Aguirre Tobón—and their collaborators,<br />

Juliana Márquez Zúñiga and Héctor Galindo, at the<br />

Centro de Recursos para el Análisis de C<strong>on</strong>flictos<br />

(CERAC) in Bogotá—made significant c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

in this area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> research. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>y were commissi<strong>on</strong>ed<br />

to assess a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> datasets in order to<br />

generate an estimate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scale and distributi<strong>on</strong>

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths in selected countries, as<br />

well as a meta-review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths.<br />

Feedback <strong>on</strong> preliminary chapter drafts was also<br />

provided by Richard Garfield from the World Health<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong> (WHO) and Robin Coupland in his<br />

pers<strong>on</strong>al capacity.<br />

Indirect c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths<br />

Recent surveys have stimulated debate and awareness<br />

<strong>on</strong> the way indirect deaths almost always<br />

exceed direct deaths in war z<strong>on</strong>es. For this report,<br />

research <strong>on</strong> indirect c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths was led by<br />

Debarati Guha-Sapir, Olivier Degomme, Chiara<br />

Altare, and Ruwan Ratnayake, all members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a<br />

team <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> epidemiologists at the Centre for Research<br />

<strong>on</strong> the Epidemiology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Disasters (CRED) in Brussels.<br />

On the basis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a systematic review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dozens <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

populati<strong>on</strong>-based surveys undertaken in c<strong>on</strong>flictaffected<br />

countries, these experts established a<br />

series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the indirect costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

c<strong>on</strong>flict. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir work was supported with case studies<br />

<strong>on</strong> mortality in Sierra Le<strong>on</strong>e and South Sudan<br />

compiled by, am<strong>on</strong>g others, Catrien Bijleveld,<br />

Lotte Hoex, and Shanna Mehlbaum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the VU<br />

University Amsterdam. Jorge Restrepo and Olivier<br />

Degomme carried out critical research for the<br />

box <strong>on</strong> armed violence in Iraq. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> editors thank<br />

Richard Garfield, Colin Mathers, and Alex Butchart<br />

at WHO, who also provided input into the estimates<br />

produced in this report.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence after war<br />

Public health experts and humanitarian workers<br />

have l<strong>on</strong>g recognized that armed violence can<br />

actually escalate in the aftermath <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war. Astri<br />

Suhrke and Torunn Wimpelmann Chaudhary from<br />

the Chr. Michelsen Institute in Norway provided<br />

a critical c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> that formed the basis for<br />

the chapter <strong>on</strong> post-war armed violence. Astri<br />

Suhrke and Ingrid Samset also issued a critique<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predictive models <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war <strong>on</strong>set, while Sim<strong>on</strong><br />

Reich from the Ford Institute for Human Security<br />

at the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pittsburgh supplied evidence<br />

relating to the forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence faced by<br />

refugees and internally displaced pers<strong>on</strong>s. Richard<br />

Cincotta from the L<strong>on</strong>g Range Analysis Unit <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>al Intelligence Council in Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D.C.,<br />

provided insight into the ‘youth bulge’ and the<br />

way patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> demography can affect future<br />

trends in armed violence. Finally, Frances Stewart<br />

and Rachael Diprose from the Centre for Research<br />

<strong>on</strong> Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity at<br />

Queen Elizabeth House, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oxford,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fered insight into the relati<strong>on</strong>ships between<br />

horiz<strong>on</strong>tal inequality and armed violence.<br />

N<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence<br />

Although homicidal violence is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the better<br />

indicators <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the extent and global distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

armed violence, disaggregated data and analysis<br />

are strikingly limited. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> editors based this chapter<br />

<strong>on</strong> data from and the publicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the United<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>s Office <strong>on</strong> Drugs and Crime, as well as<br />

other publicly available sources. This evidence<br />

base allowed for regi<strong>on</strong>al and subregi<strong>on</strong>al comparis<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> homicide rates. Additi<strong>on</strong>al inputs were<br />

provided by CERAC and colleagues from WHO.<br />

Ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> debate <strong>on</strong> the ec<strong>on</strong>omic costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

tends to focus narrowly <strong>on</strong> war. Much less<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> are ec<strong>on</strong>ometric assessments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> homicidal<br />

or other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. Nevertheless,<br />

in either case, large-scale datasets tend to be<br />

ix<br />

ACK N OWLEDGEMENTS<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

x analysed to model the relati<strong>on</strong>ships between<br />

armed violence and gross domestic product (GDP)<br />

losses over time. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> chapter <strong>on</strong> the ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence seeks to widen the lens<br />

and account for the multi-dimensi<strong>on</strong>al impacts.<br />

Carlos Bozzoli, Tilman Brück, Thorsten Drautzburg,<br />

and Sim<strong>on</strong> Sottsas at the Deutsches Institut für<br />

Wirtschaftsforschung in Berlin provided an overview<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> approaches to measuring the ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

costs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. Likewise, James Putzel<br />

from the Crisis States Research Centre at the L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong><br />

School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ec<strong>on</strong>omics and Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaci<strong>on</strong>es<br />

Internaci<strong>on</strong>ales in Bogotá provided a background<br />

paper <strong>on</strong> the efficiency and distributi<strong>on</strong> effects<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. Jorge Restrepo, Brodie Fergus<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Juliana Márquez Zúñiga, Adriana Villamarín,<br />

Katherine Aguirre Tobón, and Andrés Mesa <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

CERAC established a robust estimate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>flict and criminal violence.<br />

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence against women<br />

As a first step to generating a more nuanced understanding<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> what is and is not known about the<br />

gendered impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence—particularly<br />

the implicati<strong>on</strong>s for women and girls—Megan<br />

Bastick and Karin Grimm from the Centre for the<br />

Democratic C<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> Forces and Jasna<br />

Lazarevic from the Small Arms Survey were tasked<br />

with reviewing the state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the art <strong>on</strong> the issue. Rahel<br />

Kunz from the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lucerne helped integrate<br />

the various c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s into the chapter and ensured<br />

that the gender dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

were underscored throughout the report.<br />

Other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> chapter <strong>on</strong> other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

combines a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> disparate strands. Thanks<br />

are extended to Dennis Rodgers from Manchester<br />

University, together with Chris Stevens<strong>on</strong> and<br />

Robert Muggah from the Small Arms Survey for<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributing with their work <strong>on</strong> gangs. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> secti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>on</strong> extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances<br />

is based <strong>on</strong> a background study prepared<br />

by Sabine Saliba. Eric M<strong>on</strong>gelard <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Special<br />

Procedures Branch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Office <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the High Commissi<strong>on</strong>er<br />

for Human Rights (OHCHR), as well as<br />

Claudia de la Fuente <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the OHCHR’s Working Group<br />

<strong>on</strong> Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, provided<br />

valuable comments. David Cingranelli <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Binghamt<strong>on</strong> University and David L. Richards<br />

from the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Memphis kindly facilitated<br />

the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> material from the Cingranelli-Richards<br />

Human Rights Data Project. C<strong>on</strong>trol Risks, a private<br />

risk c<strong>on</strong>sultancy firm, provided generous<br />

insight into their data <strong>on</strong> kidnap for ransom cases<br />

and we thank Lara Sym<strong>on</strong>s for facilitating this<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>. Finally, Larissa Fast from the Kroc<br />

Institute for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Peace Studies at the<br />

University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Notre Dame and Elizabeth Rowley <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Public Health<br />

in Baltimore c<strong>on</strong>tributed new findings <strong>on</strong> global<br />

trends in aid worker victimizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Finally, thanks must be extended to the participants<br />

in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> core group. Under<br />

the guidance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its chair, Ambassador Thomas<br />

Greminger from the Swiss Federal Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Foreign Affairs, the core group provided strategic<br />

guidance for the report. Together with Anna Ifkovits-<br />

Horner, Elisabeth Gilgen, and R<strong>on</strong>ald Dreyer, the<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Switzerland in particular must be<br />

specially recognized. It should be recalled that the<br />

report is an independent c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> and Development<br />

and does not necessarily reflect the views <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Switzerland or the states signatories<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. While the report is<br />

a collective effort, the editors are resp<strong>on</strong>sible for<br />

any errors and omissi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fact or judgment.

Executive Summary<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence imposes a tremendous<br />

human and ec<strong>on</strong>omic burden <strong>on</strong> individuals,<br />

families, and communities. More<br />

than 740,000 people die each year as a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the violence associated with armed c<strong>on</strong>flicts and<br />

large- and small-scale criminality. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> majority<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these deaths—as many as 490,000—occur<br />

outside war z<strong>on</strong>es. This figure shows that war is<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> many forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence, and in<br />

most regi<strong>on</strong>s not the most important <strong>on</strong>e.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence is spread across age groups but<br />

affects certain groups and regi<strong>on</strong>s disproporti<strong>on</strong>ately.<br />

It is the fourth leading cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> death<br />

for pers<strong>on</strong>s between the ages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 15 and 44 worldwide.<br />

In more than 40 countries, it is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

top ten causes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> death. In Latin America and<br />

Africa, armed violence is the seventh and ninth<br />

leading cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> death, respectively (Peden,<br />

McGee, and Krug, 2002; WHO, 2008b). 1 Yet certain<br />

demographic groups (especially young men) and<br />

geographic regi<strong>on</strong>s are much more affected than<br />

others. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> full dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence are<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten invisible unless they are closely m<strong>on</strong>itored<br />

and analysed.<br />

Bey<strong>on</strong>d the chilling calculus <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> deaths, armed<br />

violence imposes huge human, social, and ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

costs <strong>on</strong> states and societies. An untold<br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> people each year are injured—<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten<br />

suffering permanent disabilities—and many live<br />

with pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ound psychological as well as physical<br />

scars. 2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> damaging effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

include such things as physical and mental disabil-<br />

ities, brain and internal organ injuries, bruises and<br />

scalds, chr<strong>on</strong>ic pain syndrome, and a range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sexual<br />

and reproductive health problems (WHO, 2008a).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence also corrodes the social fabric <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

communities, sows fear and insecurity, destroys<br />

human and social capital, and undermines devel-<br />

opment investments and aid effectiveness. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

death and destructi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war—which ebbs and<br />

flows from year to year and is c<strong>on</strong>centrated in a<br />

few countries—reduces gross domestic product<br />

(GDP) growth by more than two per cent annu-<br />

ally, with effects lingering many years after the<br />

fighting ends. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> ec<strong>on</strong>omic cost—in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

lost productivity—<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence<br />

(large- and small-scale criminal and political<br />

violence) is USD 95 billi<strong>on</strong> and could reach up<br />

to USD 163 billi<strong>on</strong> annually worldwide.<br />

Undertaking research and gathering data <strong>on</strong> armed<br />

violence is difficult and <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten c<strong>on</strong>troversial. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

has political implicati<strong>on</strong>s (even when the violence<br />

itself may not be politicized) and is seldom random.<br />

Different groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten have an interest in under-<br />

stating or c<strong>on</strong>cealing the scope <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> lethal armed<br />

violence, making the collecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reliable data<br />

and impartial analysis particularly challenging.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> promoti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effective and practical measures<br />

to reduce armed violence nevertheless depends<br />

<strong>on</strong> the development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reliable informati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its causes and c<strong>on</strong>sequences. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report draws <strong>on</strong><br />

a wide variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sources and datasets to provide<br />

1<br />

E X ECU T I V E SUMM A RY<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

2 a comprehensive picture <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the worldwide scope,<br />

scale, and effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. It c<strong>on</strong>tributes<br />

to the generati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a broader evidence base <strong>on</strong> the<br />

links between armed violence and development and<br />

is part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> implementing the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Geneva</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Declarati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> and Development.<br />

Dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

For the purposes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this report, armed violence is<br />

the intenti<strong>on</strong>al use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> illegitimate force (actual or<br />

threatened) with arms or explosives, against a<br />

pers<strong>on</strong>, group, community, or state, that under-<br />

mines people-centred security and/or sustainable<br />

development.<br />

This definiti<strong>on</strong> covers many acts, ranging from<br />

the large-scale violence associated with c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

and war to inter-communal and collective violence,<br />

organized criminal and ec<strong>on</strong>omically motivated<br />

violence, political violence by different actors or<br />

groups competing for power, and inter-pers<strong>on</strong>al<br />

and gender-based violence. 3<br />

This report provides cross-regi<strong>on</strong>al and interna-<br />

ti<strong>on</strong>al comparis<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most dramatic<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sequences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence: direct c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

deaths, indirect c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths, post-c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

mortality, and n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths such as homi-<br />

cide, disappearances, kidnappings, and aid worker<br />

killings. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>se forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence are usually<br />

the best documented, and as leading indicators<br />

can provide a good basis for understanding the<br />

scope and distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence around<br />

the world and for exploring other, less prominent<br />

dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report also explores in a separate chapter<br />

the less-visible forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence against women,<br />

and where possible c<strong>on</strong>siders the gendered<br />

dimensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most prominent forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence. While the overwhelming majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

victims (and perpetrators) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence are<br />

men, there are gender-specific forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violence<br />

that warrant greater analysis and that are poorly<br />

documented.<br />

Key findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the report are that:<br />

more than 740,000 people have died directly<br />

or indirectly from armed violence—both c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

and criminal violence—every year in recent years.<br />

more than 540,000 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these deaths are violent,<br />

with the vast majority occurring in n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

settings.<br />

at least 200,000 people—and perhaps many<br />

thousands more—have died each year in c<strong>on</strong>-<br />

flict z<strong>on</strong>es from n<strong>on</strong>-violent causes (such as<br />

malnutriti<strong>on</strong>, dysentery, or other easily pre-<br />

ventable diseases) that resulted from the<br />

effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war <strong>on</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

between 2004 and 2007, at least 208,300<br />

violent deaths were recorded in armed c<strong>on</strong>-<br />

flicts—an average <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 52,000 people killed per<br />

year. This is a c<strong>on</strong>servative estimate including<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly recorded deaths: the real total may be<br />

much higher.<br />

the annual ec<strong>on</strong>omic cost <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

in n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict settings, in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> lost produc-<br />

tivity due to violent deaths, is USD 95 billi<strong>on</strong><br />

and could reach as high as USD 163 billi<strong>on</strong>—<br />

0.14 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the annual global GDP.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>se figures, which are explained in detail in<br />

different chapters in this report, underscore that<br />

violent deaths in n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict settings and indi-<br />

rect deaths in armed c<strong>on</strong>flicts comprise a much<br />

larger proporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the global burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence than the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> people dying violently<br />

in c<strong>on</strong>temporary wars.

Figure 1 captures graphically the distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the different categories <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> deaths within the glo-<br />

bal burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> small green<br />

circles illustrate the direct burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violent<br />

death in c<strong>on</strong>flict, including both civilians and<br />

combatants. It represents roughly seven per cent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the total global burden. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> larger blue circle<br />

represents the indirect deaths from violent c<strong>on</strong>-<br />

flict—some 27 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the total. And violent<br />

deaths in n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict settings—490,000 per<br />

year—represent two-thirds (66 per cent) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

total. 4 Bey<strong>on</strong>d this lie the untold number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> phys-<br />

ically injured or psychologically harmed people<br />

who also bear part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the global burden <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence.<br />

Traditi<strong>on</strong>ally, these various manifestati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence have been treated separately, as if their<br />

underlying causes and dynamics were fundamen-<br />

tally different. Yet the changing nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence—including the rise <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ec<strong>on</strong>omically<br />

motivated wars, the blurring <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the line between<br />

political and n<strong>on</strong>-political violence, the growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

trans-nati<strong>on</strong>al criminal gangs, the expansi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

n<strong>on</strong>-state armed groups, and persistently high<br />

levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> insecurity in most post-c<strong>on</strong>flict situati<strong>on</strong>s—<br />

makes drawing clear distincti<strong>on</strong>s between different<br />

forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence practically and analyti-<br />

cally impossible.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>tinuing to treat these different forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence separately also impedes the develop-<br />

ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> coherent and comprehensive violence<br />

preventi<strong>on</strong> and reducti<strong>on</strong> policies at the interna-<br />

ti<strong>on</strong>al and local level. Since <strong>on</strong>e goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Global</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Burden</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Armed</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Violence</str<strong>on</strong>g> report is to promote a<br />

better understanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the negative impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

armed violence <strong>on</strong> human, social, and ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

development, it is critical to adopt the broader<br />

lens <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence rather than focusing <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its many manifestati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Figure 1 Categories <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> deaths<br />

INDIRECT CONFLICT<br />

DEATHS<br />

Battle-related deaths<br />

Civilian deaths in<br />

armed c<strong>on</strong>flict<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> report also presents the geographic distribu-<br />

ti<strong>on</strong> and c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed<br />

violence. C<strong>on</strong>flict-related deaths, which appear to<br />

have increased since 2005, are highly c<strong>on</strong>centrated:<br />

three-quarters <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all reported direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths<br />

took place in just ten countries. Ending the armed<br />

c<strong>on</strong>flicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia,<br />

and Sri Lanka in 2007 would have reduced the<br />

total number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> direct c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths by more than<br />

two-thirds. And within countries, armed violence<br />

is usually c<strong>on</strong>centrated in certain municipalities<br />

or regi<strong>on</strong>s, while other areas may be relatively<br />

untouched.<br />

DIRECT CONFLICT DEATHS<br />

Most internati<strong>on</strong>al attenti<strong>on</strong> focuses <strong>on</strong> the<br />

numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> recorded violent deaths in c<strong>on</strong>flicts.<br />

While such data potentially helps decisi<strong>on</strong>-makers<br />

and analysts assess the intensity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a war and its<br />

evoluti<strong>on</strong> over time, these relatively low figures<br />

(in the tens <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thousands) obscure the larger bur-<br />

den <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mortality arising from indirect deaths in<br />

NON-CONFLICT<br />

DEATHS<br />

3<br />

E X ECU T I V E SUMM A RY<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

4 armed c<strong>on</strong>flicts. A minimum estimate is that an<br />

average <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 200,000 people have died annually in<br />

recent years as indirect victims during and imme-<br />

diately following recent wars. Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these people,<br />

including women, children, and the infirm, died <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

largely preventable illnesses and communicable<br />

diseases. Yet they are every bit as much victims <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

armed violence as those who die violently, and an<br />

adequate accounting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the victims <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war has to<br />

include these indirect deaths. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> indirect<br />

deaths depends in part <strong>on</strong> the durati<strong>on</strong> and intensity<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the war, relative access to basic care and services,<br />

and the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> humanitarian relief efforts.<br />

Map 4.1 Homicide rates per 100,000 populati<strong>on</strong>, by subregi<strong>on</strong>, 2004<br />

�������<br />

Per 100,000<br />

populati<strong>on</strong><br />

>30<br />

25–30<br />

20–25<br />

10–20<br />

5–10<br />

3–5<br />

0–3<br />

Note: <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> boundaries and designati<strong>on</strong>s used <strong>on</strong> this map do not imply endorsement or acceptance.<br />

Source: UN Office <strong>on</strong> Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> ratio <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> people killed in war to those dying<br />

indirectly because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a c<strong>on</strong>flict is explored in the<br />

chapter <strong>on</strong> indirect deaths (INDIRECT CONFLICT<br />

DEATHS). Studies show that between three and<br />

15 times as many people die indirectly for every<br />

pers<strong>on</strong> who dies violently. In the most dramatic<br />

cases, such as the Democratic Republic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

C<strong>on</strong>go, up to 400,000 excess deaths per year<br />

have been estimated since 2002, many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which<br />

resulted indirectly from war. C<strong>on</strong>sequently, this<br />

report’s estimate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a global average <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 200,000<br />

indirect c<strong>on</strong>flict deaths per year should be taken<br />

as a c<strong>on</strong>servative figure.

This report also finds that the aftermath <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> war<br />

does not necessarily bring a dramatic reducti<strong>on</strong><br />

in armed violence (ARMED VIOLENCE AFTER WAR).<br />

In certain circumstances, post-c<strong>on</strong>flict societies<br />

have experienced rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence that<br />

exceed those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the c<strong>on</strong>flicts that preceded them.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>y also exhibit a 20–25 per cent risk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> relapsing<br />

into war. So l<strong>on</strong>g as such countries must c<strong>on</strong>tend<br />

with high youth bulges (exceeding 60 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the total populati<strong>on</strong>), soaring rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> unemploy-<br />

ment, and protracted displacement, the risks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

renewed armed c<strong>on</strong>flict remain high.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violent deaths occur in n<strong>on</strong>-war<br />

situati<strong>on</strong>s, as the result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> small or large-scale<br />

criminally or politically motivated armed violence<br />

(NON-CONFLICT ARMED VIOLENCE). More than<br />

490,000 homicides occurred in 2004 al<strong>on</strong>e. This<br />

represents twice the total number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> people who die<br />

directly and indirectly in armed c<strong>on</strong>flicts. As violent<br />

as wars can be, more people die in ‘everyday’—<br />

and sometimes intense—armed violence around<br />

the world than in armed c<strong>on</strong>flicts. Map 4.1 (pre-<br />

sented in Chapter 4) illustrates the distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>flict and n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence, expressed<br />

as the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> homicides per 100,000 pers<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> geographic and demographic dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

n<strong>on</strong>-c<strong>on</strong>flict armed violence are significant. Sub-<br />

Saharan Africa and Central and South America<br />

are the most seriously affected by armed violence,<br />

experiencing homicide rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> more than 20 per<br />

100,000 per year, compared to the global average<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 7.6 per 100,000 populati<strong>on</strong>. Countries in South-<br />

ern Africa, Central America, and South America—<br />

including Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala,<br />

Jamaica, South Africa, and Venezuela—report<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g the highest recorded rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> violent death<br />

in the world, ranging from 37 (Venezuela) to 59<br />

(El Salvador) per 100,000 in 2005, as reported<br />

by <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficial police statistics. 5<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> weap<strong>on</strong> matters. As much as 60 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all<br />

homicides are committed with firearms—ranging<br />

from a high <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 77 per cent in Central America to a<br />

low <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 19 per cent in Western Europe. And there is<br />

a gendered comp<strong>on</strong>ent to armed violence: although<br />

most victims are men, the killing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> women varies<br />

by regi<strong>on</strong>: in ‘high-violence’ countries, women<br />

generally account for about 10 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

victims, while they represent up to 30 per cent in<br />

‘low-violence’ countries. This suggests that intim-<br />

ate partner violence does not necessarily rise and<br />

fall with other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence, and may<br />

not decline as other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence are<br />

reduced.<br />

Photo ! A policeman<br />

carries a child away<br />

during a gun battle in<br />

Tijuana, Mexico, 2008.<br />

© Jorge Duenes/Reuters<br />

5<br />

E X ECU T I V E SUMM A RY<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7

GLOBAL BURDEN <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ARMED VIOLENCE<br />

6 <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are a host <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> other forms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> armed violence<br />

Photo " People stand at<br />

the scene <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a car bomb<br />

in the Campsara district<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Baghdad, 2008.<br />