You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Fotografía: Armando Álvarez Basterrechea<br />

PERÚ 2008<br />

24<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL<br />

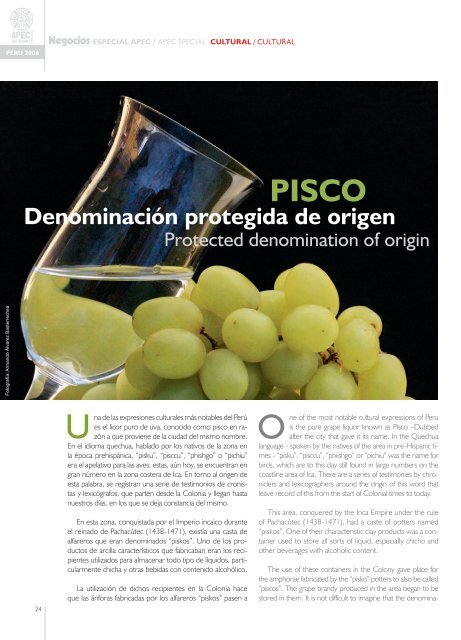

PISCO<br />

Denominación protegida de origen<br />

Protected denomination of origin<br />

U O<br />

na de las expresiones culturales más notables del Perú<br />

es el licor puro de uva, conocido como pisco en razón<br />

a que proviene de la ciudad del mismo nombre.<br />

En el idioma quechua, hablado por los nativos de la zona en<br />

la época prehispánica, “pisku”, “pisccu”, “phishgo” o “pichiu”<br />

era el apelativo para las aves; estas, aún hoy, se encuentran en<br />

gran número en la zona costera de Ica. En torno al origen de<br />

esta palabra, se registran una serie de testimonios de cronistas<br />

y lexicógrafos, que parten desde la Colonia y llegan hasta<br />

nuestros días, en los que se deja constancia del mismo.<br />

En esta zona, conquistada por el Imperio incaico durante<br />

el reinado de Pachacútec (1438-1471), existía una casta de<br />

alfareros que eran denominados “piskos”. Uno de los productos<br />

de arcilla característicos que fabricaban eran los recipientes<br />

utilizados para almacenar todo tipo de líquidos, particularmente<br />

chicha y otras bebidas con contenido alcohólico.<br />

La utilización de dichos recipientes en la Colonia hace<br />

que las ánforas fabricadas por los alfareros “piskos” pasen a<br />

CuLtuRAL / CULtUrAL<br />

ne of the most notable cultural expressions of Peru<br />

is the pure grape liquor known as Pisco –Dubbed<br />

after the city that gave it its name. In the Quechua<br />

language - spoken by the natives of the area in pre-Hispanic times<br />

- “pisku”, “pisccu”, “phiishgo” or “pichiu” was the name for<br />

birds, which are to this day still found in large numbers on the<br />

coastline area of Ica. There are a series of testimonies by chroniclers<br />

and lexicographers around the origin of this word that<br />

leave record of this from the start of Colonial times to today.<br />

This area, conquered by the Inca Empire under the rule<br />

of Pachacútec (1438-1471), had a caste of potters named<br />

“piskos”. One of their characteristic clay products was a container<br />

used to store all sorts of liquid, especially chicha and<br />

other beverages with alcoholic content.<br />

The use of these containers in the Colony gave place for<br />

the amphorae fabricated by the “pisko” potters to also be called<br />

“piscos”. The grape brandy produced in the area began to be<br />

stored in them. It is not difficult to imagine that the denomina-

Gonzalo Gutiérrez<br />

Presidente de la Reunión de Altos Funcionarios (SOM) del APEC 2008 y Viceministro Secretario<br />

General de Relaciones Exteriores. Es experto en el pisco y autor de “El Pisco: apuntes<br />

para la defensa internacional de la denominación de origen peruana” (2003).<br />

Chair of APEC 2008 Senior Official’s Meeting (SOM) and Vice Minister and Secretary-General of the<br />

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He is an expert on Pisco and the author of “Pisco: Notes for the International<br />

Defense of the Peruvian Denomination of Origin” (2003).<br />

denominarse también “piscos”. En ellas se empezó a almacenar<br />

el aguardiente de uva producido en la zona. No es<br />

difícil imaginar que la denominación fue transferida rápidamente<br />

del continente al contenido, de modo que pisco ya<br />

no solo fue el recipiente que atesoraba el licor, sino que la<br />

bebida misma pasó a conocerse con esa palabra.<br />

El primer mapa conocido del Perú fue elaborado por el<br />

geógrafo Diego Méndez, en 1574 1 . A pesar de lo impreciso<br />

de la cartografía de la época, ya en ese momento él identifica<br />

claramente el puerto de Pisco, lugar de origen del licor, ubicándolo<br />

al sur de la Ciudad de los Reyes, en lo que designa<br />

como “Golfo de Lima”.<br />

La referencia más antigua que existe sobre la producción<br />

de aguardiente en la zona fue ubicada por el historiador<br />

y presidente de la Academia Peruana del Pisco, Lorenzo<br />

Huerta 2 , en un testamento firmado en 1613. Según dicho<br />

documento, un habitante de Ica, conocido como Pedro Manuel,<br />

El Griego, dejaba como parte de su herencia ciento<br />

sesenta botijas de pisco.<br />

Acerca del creciente comercio de pisco que se produjo a<br />

partir del siglo XVIII, algunas cifras son ilustrativas. Así, ya entre<br />

1701 y 1704, desde el Callao, se exportaba un promedio de<br />

70 botijuelas de aguardiente con destino a Valparaíso. En ese<br />

mismo período, se enviaban a Valdivia, en Chile, 596 botijuelas<br />

de aguardiente y 19 de vino. En 1704 se embarcaron hacia<br />

Concepción, también en Chile, 115 botijuelas del mismo<br />

licor 3 . Sin embargo, esas cifras son ínfimas comparadas con la<br />

exportación de 10,102 y 28,698 botijuelas a Guayaquil y Panamá,<br />

respectivamente, ambas realizadas también en 1704.<br />

Pero quizá uno de los testimonios más reveladores es el<br />

que escribe el científico suizo Jakob von Tschudi, quien viajó<br />

por el Perú entre 1838 y 1842. Refiriéndose a la producción<br />

de uva en la zona, la describe de la siguiente manera:<br />

“Las uvas son de excelente calidad, muy jugosas y dulces.<br />

De la mayor parte se destila aguardiente, el cual, como se<br />

comprenderá, es exquisito. Todo el Perú y una gran parte<br />

de Chile se aprovisionan de esta bebida del valle de Ica. El<br />

aguardiente común se llama aguardiente de pisco, porque<br />

es embarcado de este puerto”. 4<br />

También es destacable el prestigio que poseía el pisco<br />

peruano como producto de exportación en el siglo XIX.<br />

tion was quickly transferred from the container to the content,,<br />

in the way that pisco was not only the container of the treasured<br />

liquor, but the drink became to be known by the same word.<br />

The first known map of Peru was drafted by the geographer,<br />

Diego Mendez in 1574 1 . In spite of the lack of accuracy for the<br />

time, he clearly identifies the Port of Pisco, place of origin of the<br />

liquor, locating it south of the City of Kings – designated as the<br />

“Gulf of Lima”.<br />

The oldest reference there is on the production of this brandy<br />

is in the area pointed out by the historian and President of<br />

the Peruvian Academy of Pisco, Lorenzo Huerta 2 . According to<br />

a will signed in 1613, an Ica local man known as Pedro Manuel,<br />

“The Greek”, left 170 Pisco botijas as part of his state.<br />

With regards to the growing Pisco trade that started at the<br />

beginning of the 18th Century, some numbers are illustrative.<br />

Between 1701 and 1704 an average of 70 botijuelas of the brandy<br />

were exported from Callao to Valparaiso. In that same period,<br />

596 botijuelas of the brandy and 19 of wine were sent to Valdivia<br />

in Chile. In 1704, 115 botijuelas of the same liquor 3 were shipped<br />

to Concepcion, also in Chile. Nevertheless, these numbers<br />

are slim in comparison to the export of 10,102 botijuelas to<br />

Guayaquil and 28,698 botijuelas to Panama, both shipped in the<br />

same year.<br />

25

PERÚ 2008<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLtuRAL / CULtUrAL<br />

Una referencia particularmente interesante es la contenida<br />

en el libro de Herbert Ashbury 5 , en el que se describe parte<br />

de la historia de la ciudad estadounidense de San Francisco.<br />

En este trabajo Ashbury señala que “…el Bank Exchange era<br />

especialmente famoso por el ‘Pisco Punch’, inventado por Duncan<br />

Nichol, uno de los más reputados barmen [...]. Durante<br />

la década de 1870 era de lejos la bebida más popular en San<br />

Francisco, a pesar que se vendía a 25 centavos el vaso, un<br />

precio alto para aquellos días. El secreto de su preparación<br />

desapareció con Nichol, quien nunca lo divulgó [...]. Pero las<br />

descripciones del San Francisco de aquel período, abundan en<br />

referencias líricas a su sabor y potencia, y debe haber sido ‘la<br />

crème de la crème’ de las bebidas. Su base era el aguardiente<br />

de Pisco, que era destilado de la uva conocida como Italia o la<br />

Rosa del Perú, y se denominó así debido al puerto peruano por<br />

donde era embarcado [...].<br />

En relación a este ponche, que devino en característico<br />

de San Francisco, José Antonio Schiaffino ha escrito un interesante<br />

estudio 6 que revela la larga trayectoria de dicha<br />

preparación, que inclusive se prolonga luego de la prohibición<br />

en Estados Unidos hasta la década de 1950. El autor<br />

demuestra la existencia de diversos locales especializados en<br />

su elaboración, siendo quizá el más característico el conocido<br />

como “House of Pisco”, que se ubicaba en el 580 de<br />

Pacific Avenue, en San Francisco.<br />

También se cuenta que el 29 de enero de 1938 se inauguró<br />

en esa ciudad una placa conmemorando la invención del<br />

renombrado “Pisco Punch”. Asimismo, en una nota al pie de<br />

página del libro de Ashbury, se señala que Thomas W. Knox,<br />

But perhaps, one of the most revealing testimonies is the<br />

one written by the Swiss scientist, Jakob von Tschudi, who<br />

travelled in Peru between 1838 and 1842. He describes the<br />

grape production of the area in the following manner:<br />

“The grapes are of excellent quality, very juicy and<br />

sweet. The majority are distilled for brandy, which is, understandably,<br />

exquisite. All of Peru and a large part of Chile<br />

store this beverage from the Valley of Ica. This common<br />

brandy is called Pisco brandy given that it is shipped at that<br />

port.” 4<br />

What is also worth noting is the prestige Peruvian Pisco<br />

had as an export product in the 19th Century. A particularly<br />

interesting reference is found in the book by Herbert<br />

Ashbury 5 , in which he describes part of the history of the<br />

American city of San Francisco. In this piece, Ashbury indicates<br />

that “… The Bank Exchange was especially noted<br />

for Pisco Punch, invented by Duncan Nichol, one of the<br />

most famous bartenders [...]. During the eighteen-seventies<br />

it was by far the most popular drink in San Francisco,<br />

although it was sold for twenty-five cents a glass, a high<br />

price for those days. The secret of its preparation died with<br />

Nichol, for he would never divulge it. [...]. But descriptions<br />

of the San Francisco of the period abound with lyrical<br />

accounts of its flavor and potency, and it must have been<br />

the crème de la crème of beverages. Its base was Pisco<br />

brandy, which was distilled from the grape known as Italia,<br />

or La Rosa del Peru, and was named for the Peruvian port<br />

from which it was shipped. [...].<br />

In regards to this punch, which became characteristic<br />

of San Francisco, José Antonio Schiaffino has written up<br />

an interesting study 6 that reveals the long trajectory of said<br />

preparation, that even continued after the ban in the States<br />

during the 1950’s. The author reveals the existence<br />

of diverse places, specialized in its preparation - the most<br />

characteristic one perhaps being “House of Pisco” which<br />

was on 580 Pacific Avenue, San Francisco.<br />

Also lore tells us that on Jan. 29, 1938, the city received<br />

a plaque commemorating the invention of the renowned<br />

“Pisco Punch”. In the same manner, Ashbury points out in<br />

an author’s note from his book Underground or Life Below<br />

the Surface (pg. 253) that Thomas W. Knox noted that<br />

Pisco was also used in a drink called “Button Punch”. This<br />

being described by the English author, Rudyard Kipling in<br />

his work From Sea to Sea (1899), in the following manner:

en su libro Underground or Life Below the<br />

Surface (p. 253), anotaba también que el<br />

pisco fue utilizado en una bebida denominada<br />

“Button Punch”. Esta es descrita por<br />

el autor inglés Rudyard Kipling, en su obra<br />

“From Sea to Sea” (1899), de la siguiente<br />

manera:<br />

“...tengo la teoría que está compuesto<br />

de alas de querubín, de la gloria de un<br />

amanecer tropical,<br />

y de las nubes rojas de un atardecer,<br />

y de fragmentos de las obras épicas perdidas<br />

de antiguos maestros…<br />

es el producto más sublime y noble de<br />

esta época”.<br />

En la actualidad, a nivel internacional,<br />

quizá el tratado más importante que protege<br />

las denominaciones de origen como<br />

la del pisco es el Arreglo de Lisboa relativo<br />

a la Protección de las Denominaciones<br />

de Origen y su Registro Internacional, de<br />

la Organización Mundial de la Propiedad<br />

Intelectual (OMPI). La definición del Arreglo<br />

de Lisboa sobre la “denominación de<br />

origen” constituye el estándar internacional<br />

que se viene aplicando de manera casi<br />

universal.<br />

El 16 de febrero de 2005, el Perú se<br />

adhirió a dicho Arreglo y, como resultado,<br />

los 26 países miembros del tratado<br />

han reconocido la peruanidad de la denominación<br />

pisco. Adicionalmente, el<br />

Perú cuenta con un gran bagaje de reconocimientos<br />

internacionales de esta<br />

bebida de bandera. Los países andinos,<br />

Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia y Venezuela,<br />

la reconocen como eminentemente<br />

peruana. Lo mismo hacen países como<br />

Panamá, Guatemala, Costa Rica, El Salvador,<br />

Nicaragua, Cuba, Israel y República<br />

Dominicana. Igualmente ocurre en el Asia<br />

Pacífico: Tailandia inauguró su registro de<br />

denominaciones de origen incorporando<br />

al pisco del Perú como su primer reconocimiento<br />

internacional. También Vietnam<br />

publicidad<br />

publicidad<br />

publicidad<br />

publicidad

PERÚ 2008<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLtuRAL / CULtUrAL<br />

PISCO SOuR<br />

Bebida nacional del Perú<br />

El pisco sour es un cocktail a base de pisco, jugo<br />

de limón, azúcar blanca, clara de huevo y hielo<br />

picado.<br />

Ingredientes<br />

2 onzas de pisco<br />

1/2 onza de jugo de limón<br />

3/4 onzas de azúcar blanca ó 1/2 onza de jarabe<br />

de goma<br />

1/3 de clara de huevo<br />

3-4 cubos de hielo<br />

Preparación<br />

Poner los ingredientes en una coctelera con<br />

bastante hielo y agregar la clara. Agitar la coctelera,<br />

poner un colador y vaciar el contenido de un vaso<br />

de 4 onzas. Servir con dos gotitas de amargo de<br />

angostura u, opcionalmente, canela molida.<br />

y Singapur lo reconocen como una denominación peruana.<br />

En el caso de los tratados de libre comercio con los Estados<br />

Unidos y Canadá, se ha reconocido que el pisco es un licor<br />

de origen peruano.<br />

Para los peruanos el pisco es un motivo especial de orgullo.<br />

Su calidad, así como la versatilidad de las preparaciones<br />

que pueden elaborarse con este fino licor, seguramente harán<br />

las delicias de todos los participantes en la Cumbre de<br />

APEC en el Perú.n<br />

1 Didaro Mendezio, Peruvvia Auriferae Regionis Typus, 1574.<br />

2 Lorenzo Huertas, Producción de vinos y sus derivados en Ica. Siglos XVI-XVII. Lima,<br />

1988, p. 24.<br />

3 Banco Latino, Crónicas y relaciones que se refieren al origen y virtudes del pisco, bebida<br />

tradicional y patrimonio del Perú. Lima, 1990.<br />

4 Johann Jakob von Tschudi, Testimonio del Perú [1838-1842]. Lima, 1966, p. 202-203.<br />

La obra fue originalmente impresa en San Gallen, Suiza, en 1846.<br />

5 Herbert Asbury, The Barbary Coast: An informal History of the San Francisco Underworld.<br />

Chapter 9: “God Help the Poor Sailor”. Garden City Publishing Company, Inc.<br />

New York, 1933, pp. 226-227.<br />

6 José Antonio Schiaffino, Pisco Punch: los ponches de pisco en San Francisco, Estados<br />

Unidos. Lima, 2005<br />

1 Didaro Mendezio, Peruvvia Auriferae Regionis Typus, 1574.<br />

2 Lorenzo Huertas, Producción de vinos y sus derivados en Ica. Siglos XVI-XVII. Lima,<br />

1988, p. 24.<br />

3 Banco Latino, Crónicas y relaciones que se refieren al origen y virtudes del pisco, bebida<br />

tradicional y patrimonio del Perú. Lima, 1990.<br />

4 Johann Jakob von Tschudi, Testimonio del Perú [1838-1842]. Lima, 1966, p. 202-203.<br />

This book was originally printed in San Gallen, Switzerland, in 1846.<br />

5 Herbert Asbury, The Barbary Coast: An informal History of the San Francisco Underworld.<br />

Chapter 9: “God Help the Poor Sailor”. Garden City Publishing Company, Inc.<br />

New York, 1933, pp. 226-227.<br />

6 José Antonio Schiaffino, Pisco Punch: los ponches de pisco en San Francisco, Estados<br />

Unidos. Lima, 2005.<br />

PISCO SOuR<br />

Peru’s National Drink<br />

Pisco Sour is a cocktail made of Pisco, lime<br />

juice, white sugar, egg white and chopped<br />

ice.<br />

Ingredients<br />

2 ounces of Pisco<br />

1/2 ounce lime juice<br />

3/4 ounces of white sugar or ½ ounce of<br />

sugar syrup<br />

1/3 egg white<br />

3-4 ice cubes<br />

Preparation<br />

Place ingredients in a cocktail shaker with<br />

lots of ice and add egg white. Shake cocktail<br />

shaker, strain and empty content in 4 ounce<br />

glass. Pour two drops of Angostura Bitters<br />

or powder cinnamon.<br />

“The greatest and most noble product of the times. I have a<br />

theory that it is made of wings of cherubs, the glory of a tropical<br />

dawn, the red clouds of a sunset, and fragments of long lost epic<br />

songs of dead heroes.”<br />

Currently, perhaps the most important international treaty<br />

referred to the Protection of Denomination of Origin and the<br />

International Registry is that of the Lisbon Agreement from the<br />

Wolrd Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The definition<br />

of the Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations<br />

of Origin and their International Registration constitutes the international<br />

standard applied almost universally.<br />

On February 16, 2005, Peru adhered to said Agreement,<br />

and as a result the 26 Member Countries recognized the denomination<br />

of Pisco as being Peruvian. Furthermore, Peru has a<br />

heavy load of international acknowledgements on this signature<br />

beverage. The Andean countries: Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia<br />

and Venezuela have recognized it as eminently Peruvian. The<br />

same with countries such as Panama, Guatemala, Costa Rica, El<br />

Salvador, Nicaragua, Cuba, Israel and the Dominican Republic.<br />

Likewise in Vietnam and Singapore where it is recognized as of<br />

Peruvian Denomination. In the case of the Free Trade Agreement<br />

with the United States and Canada, Pisco has been recognized<br />

as a liquor or Peruvian origin.<br />

To Peruvians, Pisco is a sense of pride. Its quality, as well as<br />

the versatility it provides in the preparations that can be made<br />

with this fine liquor will surely delight all participants of the APEC<br />

CEO Summit in Peru.n

PERÚ 2008<br />

24<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLtuRAL / CuLTurAL<br />

CARAL<br />

La civilización más antigua de<br />

The Oldest Civilization in America<br />

L T<br />

a ciudad de Cusco es conocida por haber sido la capital<br />

del Imperio inca, y Machu Picchu por haber sido<br />

el predio de uno de sus últimos soberanos; pero aún<br />

muy pocos saben que la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral fue edificada<br />

por el primer Estado político que se formó en América,<br />

4,400 años antes de que gobernaran los incas.<br />

El sistema social de Caral se formó en el continente americano<br />

en el mismo período que los otros focos civilizatorios<br />

prístinos de Mesopotamia, Egipto, India y China. Sus pobladores<br />

se adelantaron en, por lo menos, 1,800 años a los que<br />

habitaron Mesoamérica, en donde ha sido identificado otro<br />

foco civilizatorio de los seis reconocidos en el planeta. Pero, a<br />

diferencia de las civilizaciones del Viejo Mundo, que intercambiaron<br />

bienes, conocimientos y experiencias, Caral logró un<br />

desarrollo precoz, en completo aislamiento de sus coetáneas<br />

en América. Por eso, frente a aquellas civilizaciones, que se<br />

comunicaron y han compartido determinados patrones de<br />

conducta, la civilización Caral es una importante fuente de in-<br />

he City of Cusco is known for having been the capital of<br />

the Inca Empire, and Machu Picchu for having been the<br />

residence of its last emperors. Few know, however, that<br />

the Sacred City of Caral was built during the first nation state that<br />

was formed in America – 4,400 years before the Incas ruled.<br />

Caral’s social system developed in the American Continent<br />

concurrently with the other pristine earlier centers<br />

of civilization in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and China. Its<br />

people were ahead of their time in at least 1,800 years in<br />

comparison to those of Mesoamerica, one of the six recognized<br />

earlier centers of civilization. But, in contrast with the<br />

Old World civilizations, which exchanged goods, knowledge<br />

and experience, Caral managed a precocious development<br />

in complete isolation from its American peers. That is why<br />

Caral stands out as an important source of information against<br />

other civilizations that communicated and shared behavioral<br />

patterns. In addition, we have a better understanding of a different<br />

kind of development in an earlier civilization center.

Vista panorámica del sector norte de la mitad alta de la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral /<br />

Panoramic view from the higher northern half of the Sacred City of Caral<br />

América<br />

formación para aproximarnos al conocimiento de un foco de<br />

desarrollo diferente.<br />

Si bien el Perú es conocido como un país pluricultural (culturas<br />

Moche, Lima, Nazca, Chacha, Cajamarca, Huari, Colla,<br />

Lupaca, Inca, etc.) y multilingüe (lenguas mochica, quiqnam,<br />

quechua, den, aymara, puquina, etc.), se debe reconocer que<br />

hubo procesos de integración, de respuesta a los retos de la<br />

variada geografía y recursos. Así, más allá de esta diversidad,<br />

los resultados obtenidos por cada sociedad convergieron en<br />

beneficio del desarrollo nacional.<br />

En este sentido, la primera integración fue promovida y<br />

sostenida por la civilización Caral, que puso los cimientos de<br />

la organización social, política y religiosa; del manejo transversal<br />

del territorio y sus recursos; de la producción de conocimientos<br />

y su aplicación tecnológica, y de otras expresiones<br />

culturales, como el registro de la información en quipus o la<br />

extensión del quechua como lengua de relación general, etc.<br />

Ruth Shady Solís<br />

La autora es Doctora en Antropología y Arqueología y fundadora<br />

y directora del Proyecto Arqueológico Caral. Ha sido decana<br />

del Colegio de Arqueólogos del Perú, directora del Museo<br />

Nacional de Arqueología y Antropología del Perú y del Museo<br />

de Arqueología y Antropología de la u. de San Marcos.<br />

The author has a doctorate in anthropology and archeology, and is the<br />

founder and director of the Caral Archeological Project. She has been<br />

dean of the Archeological School of Peru, director of the National<br />

Archeology and Anthropology Museum of Peru, and the Museum of<br />

Archeology and Anthropology of San Marcos university.<br />

Even though Peru is recognized as a multicultural (including<br />

Moche, Lima, Nazca, Chacha, Cajamarca, Huari,<br />

Colla, Lupaca and Inca) and multilingual country (Mochica,<br />

Quiqnam, Quechua, Den, Aymara, Puquina, among others),<br />

we must also acknowledge that there were integration processes<br />

in response to the challenges posed by the varied<br />

geography and resources. The results obtained by this society<br />

were well beyond diversity and converged to benefit<br />

national development.<br />

The first integration attempt was promoted and sustained<br />

by the Civilization of Caral, which laid the foundations for<br />

social, political and religious organization; for cross-management<br />

of the territory and its resources; for the production of<br />

knowledge and its technological applications; and for other<br />

cultural expressions, such as recording information in quipus,<br />

or the extension of Quechua as the general language. These<br />

contributions would last in Andean societies throughout the<br />

thousands of years of its cultural process.<br />

Meaning and Relevance<br />

Caral - one of the oldest cities in the World (3000-2800<br />

b.c.) - is at the basin of the Supe River, in the Province of Barranca,<br />

184 kms from Lima. The city occupies 66 hectares of<br />

an alluvium terrace, 25 meters above the valley bed. There are<br />

32 public buildings, plazas, official residencies, servant residencies,<br />

and domestic units gatherings distributed in a nuclear area,<br />

divided into two halves, and a marginal area located around the<br />

perimeter. The symbolic meaning of the public buildings alerts<br />

to the fact that although they were renewed periodically, its caretakers<br />

also made sure that articulation was kept between the<br />

old and the new - between the past and the present.<br />

Developments in this oldest of civilizations was impressive.<br />

Knowledge of astronomy, math, biology, medicine, among<br />

others, was applied for climate prediction; for the elaboration<br />

of a calendar; for the construction of monumental architectonical<br />

works; for the management of soil and water through<br />

irrigation/drainage channels, and for the habilitation of farm<br />

land; for the genetic improvement of plants; for the treatment<br />

of illnesses; for the public administration and in the manufacturing<br />

of ceremonial, commercial and sumptuary artifacts. The<br />

production of knowledge, carried out by specialists, created<br />

better living conditions for the entire population.<br />

25

PERÚ 2008<br />

24<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLtuRAL / CuLTurAL<br />

Estos aportes perdurarían en las sociedades andinas a través<br />

del proceso cultural milenario.<br />

Significado y trascendencia<br />

Caral, una de las urbes más antiguas del planeta (3000-2800 a.<br />

C.), se encuentra en la cuenca media del río Supe, en la provincia<br />

de Barranca, a 184 km de Lima. La ciudad ocupa 66 hectáreas de<br />

una terraza aluvial, a 25 metros por encima del lecho del valle. En<br />

ella se distinguen 32 edificios públicos, plazas, residencias de funcionarios,<br />

residencias de servidores y agrupaciones de unidades<br />

domésticas, distribuidos en una zona nuclear, dividida en dos mitades,<br />

y una zona marginal, ubicada en la periferia. Vale remarcar<br />

el significado simbólico de los edificios públicos que, si bien eran<br />

renovados periódicamente, al mismo tiempo sus constructores<br />

cuidaban que se mantuviera la articulación entre lo previo y lo<br />

nuevo; entre el pasado y el presente.<br />

El desarrollo que tuvo esta antiquísima civilización fue impresionante.<br />

Conocimientos en astronomía, matemáticas,<br />

biología, medicina, entre otros, fueron aplicados en la predicción<br />

del clima, en la elaboración del calendario, en la construcción<br />

de obras arquitectónicas monumentales, en el manejo<br />

de los suelos y el agua por medio de canales de riego/drenaje<br />

y la habilitación de campos de cultivo, en el mejoramiento<br />

genético de las plantas, en el tratamiento de enfermedades,<br />

en la administración pública y en la manufactura de artefactos<br />

con fines ceremoniales, comerciales y suntuarios. La producción<br />

de conocimientos, realizada por especialistas, fomentó<br />

mejores condiciones de vida para toda la población.<br />

La producción de plantas alimenticias e industriales, entre<br />

ellas el algodón de varios colores, cuya fibra fue destinada a la<br />

elaboración de textiles y, sobre todo, a la confección de redes<br />

de pesca, y, por otro lado, la extracción masiva de peces, en<br />

particular de anchoveta, y de moluscos, fomentaron la especialización<br />

y la complementariedad económica. Se hizo posible,<br />

así, la acumulación del excedente productivo, la especialización<br />

laboral, el intercambio a corta y larga distancia, la división social<br />

del trabajo y la aparición de autoridades políticas.<br />

Si bien las actividades de pesca con redes y la agricultura irrigada<br />

por canales generaron excedentes productivos y fue posible el acceso<br />

a diversos bienes y a experiencias variadas, que sustentaron el<br />

desarrollo científico y tecnológico, no hubo beneficios similares en<br />

el ámbito social. Se formaron estratos sociales jerarquizados, con<br />

una muy desigual distribución de la producción social.<br />

Caral pone en evidencia la<br />

extraordinaria capacidad creadora<br />

de los habitantes del diverso<br />

territorio andino norcentral que,<br />

con esfuerzo y organización,<br />

lograron ingresar al estadio<br />

civilizatorio en forma autónoma.<br />

Caral sheds light on the<br />

extraordinary creative capacity of the<br />

people of the diverse north-central<br />

Andean territory, who with effort and<br />

organization were able to enter the<br />

earlier civilization centers in an<br />

autonomous manner.<br />

The production of edible and industrial plants (among<br />

them cotton fiber of assorted colors for the elaboration<br />

of textiles and above all, fishing nets) and the massive extraction<br />

of fish (in particular anchovies and shellfish) promoted<br />

economic complementarity and specialization. The<br />

accumulation of a productive surplus, labor specialization,<br />

short and long-distance exchange, social division of work<br />

and the appearance of political authorities was thus made<br />

possible.<br />

Net fishing and agriculture (through channel irrigation)<br />

generated production surpluses, and access to<br />

diverse goods and experiences sustained scientific and<br />

technological development. However, there were no<br />

similar benefits at the social level. Social stratification<br />

Templo del Anfiteatro de la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral / Amphitheater Temple of the Sacred City of Caral

Edificio piramidal Mayor de la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral / Main Pyramid Building of the Sacred City of Caral<br />

La distinción social se observa en la arquitectura residencial,<br />

que fue diferenciada en los varios sectores de la ciudad,<br />

en cuanto a ubicación, tamaño y al material constructivo; en<br />

la indumentaria y adornos personales, como collares y grandes<br />

orejeras en las autoridades de género masculino o las<br />

mantillas en las de género femenino. También se aprecia en<br />

los entierros humanos, individuos con anemia crónica o con<br />

evidencias físicas de trabajos forzados, o niños que recibieron<br />

tratamientos diversos de acuerdo con su estatus, conferido en<br />

relación con la posición social de sus familias.<br />

Así, Caral presenta evidencias que permiten cuestionar las<br />

concepciones previas respecto a la formación de la civilización,<br />

del Estado y de la vida urbana; pero también hace posible evaluar<br />

la propia condición humana en el planeta. Además, pone<br />

a la luz la extraordinaria capacidad creadora de los habitantes<br />

del diverso territorio andino norcentral que, con esfuerzo y<br />

organización, lograron ingresar al estadio civilizatorio en forma<br />

autónoma.<br />

Desde una perspectiva cultural, la Ciudad Sagrada de Caral<br />

está llamada a convertirse en uno de los instrumentos más<br />

importantes para fortalecer la identidad cultural y la cohesión<br />

social en nuestro país, a constituirse en un destacado símbolo<br />

identitario que mejore la autoestima nacional.n<br />

and the existence of hierarchies created an unequal and<br />

unfair distribution of production.<br />

Social distinction can be observed in residential architecture<br />

in terms of location, size and material along the different<br />

sectors of the city. It can also be observed in attire, accessories<br />

such as necklaces and earflaps in male authorities or in mantillas<br />

for females. Human burials showed individuals with chronic<br />

anemia or with physical evidence of forced labor. Children<br />

also received different treatment according to their status,<br />

conferred by the social position of their families.<br />

Caral puts into question previous notions about the developing<br />

of civilization, the role of the state and urban life. But it<br />

also makes it possible to evaluate the human condition on the<br />

planet. Furthermore, it sheds light on the extraordinary creative<br />

capacity of the people of the diverse north-central Andean<br />

territory, who with effort and organization were able to enter<br />

the earlier civilization centers in an autonomous manner.<br />

From a cultural perspective, the Sacred City of Caral is<br />

beckoned to become one of the most important instruments<br />

to strengthen cultural identity and the social cohesion<br />

in our own country. It constitutes an outstanding symbol of<br />

national identity.n<br />

25

PERÚ 2008<br />

24<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLTuRAL / CuLturAL<br />

“El Perú desde su literatura”<br />

Peru through its Literature<br />

A S<br />

partir de 1950 comienza a perfilarse en el Perú una<br />

nueva generación de escritores a los que, por colocar<br />

la ciudad en el centro de sus preocupaciones<br />

literarias, se les engloba dentro de una tendencia estética denominada<br />

“narrativa urbana”. Este último calificativo, como<br />

puede deducirse, alude también a otra narrativa previa que<br />

no era urbana y que tenía como escenario central la sociedad<br />

de los Andes.<br />

Ya se sabe que las obras literarias se basan en situaciones<br />

y personajes imaginarios; por eso hay que tomarlas como ficción.<br />

Sin embargo, buena parte de la ficción peruana de las<br />

últimas décadas ha reflejado de distinta forma el desarrollo<br />

social del Perú. Uno de los grandes dramas del país ha sido,<br />

desde sus viejos orígenes, la coexistencia de dos mundos y de<br />

dos culturas que solo en los últimos años han comenzado a<br />

fundirse y convertirse en una sola. El detonante de esta vasta<br />

transformación interna fueron las masivas migraciones de los<br />

Andes a las ciudades de la costa, en especial a Lima, a partir<br />

de los años 40 del siglo XX.<br />

Uno de los primeros relatos de esta nueva narrativa es “El<br />

niño de Junto al Cielo”, de Enrique Congrains (1932), que brilla<br />

en todas las antologías del cuento peruano por su estremecedora<br />

calidad estética y dramática; pero que también puede<br />

leerse como un retrato del momento en el que la ciudad de<br />

Lima, con apenas 500,000 habitantes, comienza a convertirse,<br />

por obra de estas oleadas migratorias, en la urbe de 8.5<br />

millones de habitantes de la actualidad.<br />

Francisco Tumi<br />

Escritor, periodista y catedrático universitario.<br />

Ha publicado la novela Las jerarquías de<br />

la noche.<br />

Writer, journalist and university professor. He has<br />

published the novel “Las jerarquías de la noche.”<br />

ince 1950, a new generation of writers started emerging<br />

in Peru placing the city in the center of their literary<br />

concerns. They are included within an esthetic tendency<br />

called “urban narrative”. As can be deduced, this defers<br />

to another, previous narrative which wasn’t urban and that<br />

had the Andes society as its center stage.<br />

It is well known that literary works are based on imaginary<br />

situations and characters - Same reason why we must take<br />

them as fiction. Nevertheless, in the last decades, a good portion<br />

of Peruvian fiction has reflected the social development<br />

of Peru in different manners. One of the biggest dramas in<br />

the country since its ancient origins is the co-existence of two<br />

worlds and two cultures that only in the last few years have<br />

begun to merge and become one. The trigger for this vast<br />

internal transformation was the massive migrations from the<br />

Andes to the cities in the coast, especially Lima, at the beginning<br />

of the 1940’s.<br />

One of the first tales of this new narrative is “El niño de<br />

Junto al cielo” by Enrique Congrains (1932), which shines in all<br />

Peruvian tales anthologies for its moving esthetic and drama.<br />

But it can also be read as a tale of the moment in which the<br />

city of Lima - with just 500,000 inhabitants - starts becoming<br />

the current city of 8.5 million due to the migratory waves.<br />

The new emerging writers from the 50’s compose stories<br />

that have this demographic and social transformation as a<br />

backdrop, and that in three generations’ time has changed the

Los nuevos escritores aparecidos a partir de los años 50<br />

componen historias que tienen como telón de fondo esa<br />

transformación demográfica y social que, en el plazo de tres<br />

generaciones, le ha cambiado el rostro al Perú. La figura más<br />

destacada de esta nueva estética es Julio Ramón Ribeyro<br />

(1929-1994), autor de algunas novelas y, sobre todo, de casi<br />

un centenar de relatos agrupados bajo el título La palabra del<br />

mudo. Ribeyro refleja como nadie una compleja sociedad urbana<br />

en trance, así como la ampliación espacial de una Lima<br />

criolla que de pronto se encuentra con ese otro país que llega<br />

en oleadas desde los Andes.<br />

Mario Vargas Llosa (1936), el narrador vivo más importante<br />

del Perú, amplía de manera vertiginosa las fronteras temáticas<br />

y estilísticas de la narrativa nacional. Su primera novela,<br />

La ciudad y los perros, no solo es un modelo artístico y un<br />

referente obligado en la literatura hispanoamericana, por la<br />

revolución técnica que significó, sino también un vívido retrato<br />

de la sociedad peruana de aquel entonces. Un colegio<br />

militar de Lima, donde convergen adolescentes provenientes<br />

de todos los rincones y clases sociales del Perú, se convierte<br />

en un microcosmos de la sociedad peruana, con su gigantesca<br />

carga de complejos, rencores, frustraciones, autoritarismo y<br />

violencia.<br />

Otra novela de Vargas Llosa, Conversación en La Catedral,<br />

tiene como telón de fondo la dictadura del general Manuel<br />

Odría (1950-56), periodo en el que el país se embarca en un<br />

proceso de rápida urbanización e industrialización y aparece<br />

una nueva clase media. En la novela de Vargas Llosa, la corrupción<br />

y la relación con el poder, la politización estudiantil y<br />

las decepciones políticas apuntalan una historia personal que<br />

se sigue leyendo con notable interés en el siglo XXI.<br />

La notable novela Un mundo para Julius, de Alfredo Bryce<br />

Echenique (1939), es una fotografía de la élite social peruana<br />

que se derrumbó a partir de los años 70. Entonces, el Perú<br />

ya estaba en camino de convertirse en otro país, con nuevos<br />

actores y reclamos sociales, y con un panorama cotidiano<br />

mucho más complejo, marcado por la creciente urbanización<br />

e internacionalización de la sociedad, la aparición de un nuevo<br />

y numeroso grupo urbano emergente -los nietos de los<br />

migrantes de los años 40 y 50- y, sobre todo, la fusión étnica<br />

y cultural, perceptible desde la música y el lenguaje hasta la<br />

gastronomía y la vida social. La narrativa peruana comienza<br />

a abrirse a temas cosmopolitas, incluso se vuelve al campo<br />

y a los Andes desde una perspectiva urbana, y el trance al<br />

siglo XXI se asume con naturalidad y con una visión universal.<br />

Exponentes de este nuevo momento de pluralidad temática<br />

face of Peru. The most prominent figure of this new esthetic<br />

is Julio Ramón Ribeyro (1929-1994), author of some novels,<br />

and above all, almost a hundred tales altogether under one<br />

title: “La palabra del mudo”. Ribeyro reflects like no one can a<br />

complex urban society in a trance, as well as the expansion of<br />

a Creole Lima that all of a sudden finds itself with that “other<br />

country” that comes in waves from the Andes.<br />

Mario Vargas Llosa (1936), the most important living<br />

narrator of Peru, expands on the thematic and style frontiers<br />

of national narrative in a vertiginous manner. His first novel<br />

“The Time of the Hero” is not only an artistic model and a<br />

mandatory reference in Hispanic-American literature because<br />

of the technical revolution it meant, but also because it is a<br />

vivid portrait of Peruvian society at the time. A military school<br />

in Lima, where teenagers from every corner and social class<br />

in Peru converge, becomes the micro cosmos of Peruvian<br />

society with its gigantic load of complexes, resentments, frustrations,<br />

authoritarianism and violence.<br />

Another of Vargas Llosa’s novels, “Conversation in the Cathedral”<br />

has General Manuel Odria’s dictatorship (1950-56)<br />

as its backdrop. This is a period in which the country goes<br />

through a quick urbanization and industrialization process, and<br />

a new middle class appears. In Vargas Llosa’s novel, corruption<br />

and the relationship to power, student politization and political<br />

deceptions signal a personal history that the 21st Century still<br />

reads with notable interest.<br />

The outstanding novel “A World for Julius” by Alfredo Bryce<br />

Echenique (1939) is a picture perfect portrait of the Peruvian<br />

social elite that began to crumble in the 70’s. At the time,<br />

25

PERÚ 2008<br />

24<br />

ESPECIAL APEC / APEC SPECIAL CuLTuRAL / CuLturAL<br />

y diversidad expresiva son Miguel Gutiérrez (1940) -aunque<br />

publicó su primera novela en 1969-, Alonso Cueto (1954) y<br />

Jaime Bayly (1965), entre muchos otros.<br />

En los años 80 del siglo pasado, el Perú entró en un nuevo<br />

trance social, como consecuencia del violento accionar del<br />

grupo terrorista Sendero Luminoso. La narrativa peruana no<br />

ha tardado en hurgar en esa dolorosa temática, comenzando<br />

por Vargas Llosa, quien se aproxima a este asunto en novelas<br />

como Historia de Mayta y Lituma en los Andes. Más tarde, dos<br />

de los más jóvenes escritores peruanos de la actualidad, Santiago<br />

Roncagliolo (1975) y Daniel Alarcón (1977) también han<br />

incursionado en esta temática en sus celebradas novelas Abril<br />

rojo y Radio Ciudad Perdida, respectivamente. Un tercer libro<br />

sobre esta temática es la colección de cuentos Toda la sangre.<br />

Antología de cuentos sobre la violencia política en el Perú.<br />

En este siglo XX, la literatura peruana continúa abriéndose<br />

a nuevos mundos. Enrique Congrains, uno de los iniciadores,<br />

hace más de 50 años, de la narrativa urbana en el Perú,<br />

acaba de publicar una novela de ciencia ficción titulada 999<br />

palabras para el planeta Tierra, cuyo punto de partida es el<br />

arribo, muy cerca de las líneas de Nazca, de una nave espacial<br />

con el encargo de pedirles a los terrícolas que se presenten<br />

ante el resto del universo con un artículo de 999<br />

palabras que se publicará en la Gran Enciclopedia<br />

Intergaláctica.n<br />

Peru was well underway to becoming another country, with<br />

new players and social complaints, and a much more complex<br />

everyday panorama. It was marked by a growing city and<br />

an internationalized society, by the appearance of a newer<br />

and bigger emerging urban group – that of the grandchildren<br />

of the immigrants from the 40’s and 50’s- and, above al, ethnic<br />

and cultural fusion, perceivable from music to language to<br />

gastronomy and social life. Peruvian narrative starts to open<br />

itself up to cosmopolitan topics. It even goes back to the fields<br />

and to the Andes from an urban perspective, and the passage<br />

into the 21st Century is assumed naturally and with a universal<br />

vision.<br />

Key players of this new multi-themed and diverse thematic<br />

are Miguel Gutiérrez (1940) (though he published his first<br />

novel in 1969), Alonso Cueto (1954) and Jaime Bayly (1965),<br />

among many others.<br />

In the 1980’s, Peru went into a new social trance as a<br />

consequence of the violent acts by the terrorist group Shining<br />

Path. Peruvian narrative didn’t take long in digging into<br />

this painful issue, starting by Vargas Llosa who approached the<br />

subject in novels such as “The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta”<br />

and “Death in the Andes”. Later on, two of the youngest Peruvian<br />

writers of current times, Santiago Roncagliolo (1975)<br />

and Daniel Alarcon (1977) also delved into the subject in<br />

their celebrated novels in “Abril rojo” and “Lost City Radio”,<br />

respectively. A third book on this matter is in the storybook<br />

collection “Toda la sangre. Antología de cuentos sobre la violencia<br />

política en el Perú.”<br />

In this Century, Peruvian literature keeps on opening<br />

itself up to new worlds. Enrique Congrains, one of the<br />

starters of Urban Peruvian Narrative over 50 years ago,<br />

just published a science fiction novel titled “999 palabras<br />

para el planeta Tierra”. Its starting point is the arrival of a<br />

spaceship very close to the Nazca Lines. The spaceship<br />

has been given instructions to ask Earthlings to introduce<br />

themselves to the universe with a 999-word article<br />

that shall be published in the Grand Intergalactic<br />

Encyclopedia.n

PERÚ 2008<br />

EDición APEc / APEC EDiTion cultuRAl / CuLTurAL<br />

Diseño de joyas<br />

en el Perú:<br />

tradición,<br />

moda y<br />

mucho estilo<br />

Jewellery Design in Peru:<br />

Tradition, Fashion and a lot of Style<br />

L A<br />

os antiguos peruanos fueron fascinados por la luz que<br />

el oro y la plata emitían, con la que evocaban el brillo<br />

del sol y la luna. Por eso, pese a que en el antiguo Perú<br />

el oro y la plata prácticamente carecían de valor comercial,<br />

las culturas trabajaron impresionantes piezas de joyería que<br />

eran usadas por los altos funcionarios y los sacerdotes, quienes<br />

aprovechaban su efecto hipnótico. Si bien hace ya casi dos<br />

milenios el desarrollo de la joyería tenía mucho que ver con el<br />

acceso a los metales, que la tierra peruana brinda a raudales,<br />

hasta la actualidad el Perú no ha dejado de ser un país joyero.<br />

Y desde hace ya algunas décadas el diseño de joyería, en<br />

especial en plata, se ha difundido de manera extraordinaria,<br />

para satisfacer las necesidades, intereses y expectativas de una<br />

gama de diferentes y exigentes compradores.<br />

La plata es un metal que habla por sí solo, tiene un brillo<br />

hermoso e intenso que, junto a su ductibilidad, lo convierte<br />

en un material idóneo para la joyería. Y en un mundo como<br />

el de la joyería, invadido de limitaciones, su costo -considerablemente<br />

menor al del oro- y su versatilidad permiten diseñar<br />

una joyería diferente. La plata otorga al diseñador la posibilidad<br />

jugar con volúmenes y formas. Puede trabajarse<br />

con piedras preciosas y semipreciosas,<br />

pero también con materiales como el cuero,<br />

las pieles, el vidrio, la paja o la madera, por poner<br />

algunos ejemplos. Las opciones son tantas<br />

que permiten que la joyería en plata provea<br />

desde accesorios de uso diario hasta verdade-<br />

ncient Peruvians were fascinated by the luminosity<br />

of gold and silver, which recalled the glistening of the<br />

sun and the moon. That is why, even though in old<br />

Peru those metals had almost no commercial value, the cultures<br />

created amazing pieces of jewellery that high priests and governors<br />

wore taking advantage of the hypnotic effect. Even though<br />

during the past two millenniums the development of jewellery<br />

had to do with access to metals, (which Peru provided in abundance,)<br />

Peru is still a jeweller country today. And a few decades<br />

ago, jewellery design -especially silver- started to really grow<br />

in order to fill the needs, interests and expectations of a range<br />

of different and demanding buyers.<br />

Silver is a metal that speaks for itself, it has a beautiful intense<br />

glow, along with its maleability makes for suitable for jewellery<br />

material. And in a world, such as the jewellery world, rich<br />

in restrictions, its cost –considerably lower than gold- and its<br />

adaptability are key factors to design inventive pieces. Silver<br />

gives the designer a chance to play with shapes and volumes.<br />

It is possible to work with precious and semi-precious stones<br />

as well as with other resources such as leather, skins, glass,<br />

straw, or wood, just to name a few. There are so many options<br />

that silver jewellery makes for everyday accessories as<br />

well as design pieces that can distinguish the owner from the<br />

rest of the pack.<br />

Jewells, Designers and Style<br />

Many believe that when it comes to Peruvian jewellery<br />

Brazalete Patc<br />

Ara Joyas

Ami Dannon<br />

Ara Joyas<br />

ras piezas de diseño, que distinguen a quienes las usan de<br />

entre el resto de personas.<br />

Joyas, diseñadores y estilos<br />

Si hablamos de joyería peruana contemporánea, muchos<br />

consideran que existen dos pilares: la gran técnica de la joyería<br />

Vasco, además valiosa escuela de joyeros, y la diseñadora italiana<br />

Graziella Laffi, cuyas importantes piezas inspiradas en el<br />

antiguo Perú siguen siendo hoy cotizadas obras de joyería.<br />

Una de las artistas que claramente ha revolucionado el diseño<br />

de joyas en el Perú es la argentina Ester Ventura, diseñadora<br />

con casi tres décadas ejecutando con maestría dicha labor.<br />

Ventura abrió paso a los diseñadores que vinieron detrás<br />

de ella al crear joyas escultóricas, anatómicas y sensuales. El<br />

there are two foundations: The great Vasco jewellery technique<br />

(as well as a valuable jewellery schoce); and the<br />

Italian designer Graziella Laffi, whose important jewellery<br />

pieces inspired in ancient Peru are still very valued today.<br />

An artist that has clearly revolutionised jewellery design<br />

in Peru is the Argentinean Ester Ventura; A designer that has<br />

been performing the work with mastery for the past three<br />

decades. By creating sculptural, anatomical and sensual pieces,<br />

Ventura made way for the designers that followed her.<br />

Her contemporary work is clearly inspired by the mystic<br />

Pre-Columbian Peru and it has been exhibited as genuine art<br />

in numerous countries. Another important jeweller is Ilaria<br />

Ciabatti, who obviously fell in love with Peruvian silver. This<br />

Florentine designer offers a harmonious line, clean and femi-<br />

25

PERÚ 2008<br />

108<br />

EDición APEc / APEC EDiTion cultuRAl / CuLTurAL<br />

misticismo del Perú precolombino es<br />

claramente inspiración de sus diseños<br />

contemporáneos, que han sido exhibidos<br />

en varios países como verdaderas<br />

piezas de arte. Otra de las más<br />

importantes joyeras en el mercado es<br />

Ilaria Ciabatti, que sin lugar a dudas se<br />

enamoró de la plata peruana. Esta diseñadora<br />

florentina ofrece una línea de<br />

joyería armónica, limpia y femenina,<br />

que sumada a su colección de platería<br />

requiere el trabajo de cerca de 120 artesanos peruanos.<br />

El mercado peruano de joyería es vasto y en la última década<br />

han surgido diseñadores con obras que destacan. Una<br />

de ellas es la orfebre Claudia Lira, cuyo estilo contemporáneo<br />

y juvenil es resultado de la combinación del mundo europeo<br />

(consecuencia de sus estudios en Holanda) y del peruano.<br />

Lira es conocida por la calidad de su joyería, caracterizada por<br />

formas simples impecablemente ejecutadas. Por otro lado<br />

Ara Joyas propone una moderna joyería de autor. Ara se da<br />

el lujo de diseñar piezas diferentes cargadas de estética y de<br />

estilo, acompañando a la plata con diversos materiales que<br />

dan posibilidades inesperadas a las joyas. Con una visión más<br />

comercial, encontramos a la joyería Mili Blume, cuya amplísima<br />

gama de joyas, principal pero no únicamente elaboradas<br />

de plata, tiene un estilo cotidiano y fácil de usar.<br />

Joyería para el Perú y el mundo<br />

El diseño de joyas en Perú es más peruano que la suma de<br />

sus partes. Los diseñadores, extranjeros o nacionales, aprovechan<br />

la calidad de la nuestra plata y la calificada mano de obra de<br />

los artesanos para crear un producto emblemático del país.<br />

El constante crecimiento económico, que incrementó la<br />

capacidad adquisitiva de los peruanos, ha tenido como consecuencia<br />

la ampliación del mercado de la joyería de diseño de<br />

plata, propiciando la aparición de muchos nuevos diseñadores.<br />

Otro factor importante para esta actividad es el incremento<br />

en la cantidad de turistas que visitan al Perú, que no solo<br />

quedan satisfechos con sus visitas, sino también con las piezas<br />

de joyería con las que regresan a sus ciudades. No obstante,<br />

las exportaciones de joyería peruana siguen siendo lideradas<br />

por productos industriales como las cadenas de plata y oro,<br />

por lo que el reto de estos diseñadores ha sido y seguirá siendo<br />

insertarse sólidamente en los mercados internacionales.<br />

Los retos están sobre la mesa… de diseño.n<br />

nine, which, added to her silverwork collection, requires the<br />

manual labour of almost 120 Peruvian craftsmen.<br />

The jewellery market in Peru is inmense and on the past<br />

decade many designers, whose work is notable, have emerged.<br />

One of them is Claudia Lira, her contemporary and<br />

youthful style is a combination of the European world (due<br />

to her studies in Holland) and the Peruvian world. Lira is<br />

well known for the quality of her jewels, branded by the<br />

simple forms she impeccably creates. On the other hand,<br />

Ara Joyas implies a modern creator’s jewellery. Ara takes the<br />

risk of designing pieces that are different and full of aesthetics<br />

and style, mixing silver with various materials that give astonishing<br />

alternatives to the jewels. With a more commercial<br />

approach, we find Mili Blume jewellery. Their largely extended<br />

range of jewels, mainly but not completely made of<br />

silver, have an everyday style that is very easy to wear.<br />

Jewellery for Peru and the World<br />

Jewellery design in Peru is as Peruvian as it can get. The<br />

foreigner and national designers create a label product of the<br />

country using the quality of our silver and the skilled labour<br />

of the artisans.<br />

The constant growth of the economy, which increased<br />

the purchasing power of Peruvians, gave as a result<br />

the expansion of the silver jewellery design market and<br />

the appearance of many new designers. Another important<br />

matter for this line of work is the growth of tourism<br />

in Peru. Tourists are pleased not only with their visit,<br />

but with the jewels they bring back to their countries.<br />

Nevertheless, jewellery export is still lead by industrial<br />

products such as gold and silver chains, which is why the<br />

challenge for these designers is, and has always been, to<br />

soundly gain access to the international markets. The bets<br />

are on the table... on the design table.n