folleto - Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

folleto - Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

folleto - Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Museo</strong> <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong>

Jules Coignet<br />

Pintores al aire libre en el bosque de Fontainebleau (detalle), 1825<br />

Painters in the Forest of Fontainebleau (detail)<br />

Barbizon, Commune de Barbizon, colección del Musée<br />

Départemental de l’École de Barbizon

IMPRESIONISMO Y AIRE LIBRE<br />

La presente exposición se propone introducir al espectador en la problemática<br />

de la pintura al óleo al aire libre, práctica artística que alcanzó su<br />

máxima expresión con el impresionismo, pero cuyos orígenes se remontan<br />

casi un siglo atrás.<br />

Desde finales del siglo XVIII, fue frecuente que los jóvenes paisajistas<br />

que se formaban en Italia se ejercitasen con pequeños estudios al óleo pintados<br />

del natural. Considerados por Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819),<br />

paisajista neoclásico y padre de la pintura al aire libre, como obras menores<br />

respecto a las composiciones finales ejecutadas en el taller pero esenciales<br />

en el aprendizaje del artista, su función principal era la de servir de ejercicios<br />

de destreza tanto para el ojo como para la mano. Indirectamente, se<br />

IMPRESSIONISM AND OPEN-AIR PAINTING<br />

The aim of this exhibition is to illustrate the development of oil painting in<br />

the open air, a technique which reached its height with Impressionism, yet<br />

originated almost a century before.<br />

From the late 18th century, young landscape artists often practised<br />

during their period of training in Italy by painting small oil studies outdoors.<br />

Regarded by Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819) — a Neo-classical landscape<br />

artist and the father of plein air painting — as minor works when compared<br />

with compositions completed in the studio, yet essential to the learning<br />

process, these studies served as exercises for developing the expertise of<br />

both hand and eye. Indirectly, the intention was that they would provide the<br />

landscape artist with a repertoire of motifs for future use in compositions

pretendía que a través de ellas el paisajista adquiriese un repertorio de posible<br />

uso en el futuro, en sus composiciones acabadas, y que recurriese a su<br />

memoria visual más que a su imaginación. En cualquier caso, los estudios al<br />

aire libre quedaban restringidos al ámbito privado del artista.<br />

Durante la primera mitad del siglo XIX, la neta distinción entre paisajes<br />

del natural y composiciones de estudio se fue desdibujando. Desde la década<br />

de 1820, se produjeron trasvases entre ambos formatos que implicaron un<br />

acabado más cuidado de los óleos pintados al aire libre y la utilización de<br />

motivos tomados del natural en las composiciones ejecutadas en el estudio.<br />

Artistas como Corot y Constable extendieron la práctica de la pintura del<br />

natural al conjunto de su producción, y pronto la moda de los estudios al<br />

óleo del natural se extendió a gran parte de Europa y de los Estados Unidos.<br />

De manera paralela, los estudios al óleo pintados al aire libre ganaron reconocimiento<br />

e independencia, sobre todo entre los artistas pertenecientes a<br />

la Escuela de Barbizon (Rousseau, Diaz de la Peña, Dupré, Daubigny, etc.),<br />

quienes frecuentaron el bosque de Fontainebleau, a unos 60 kilómetros al<br />

sur de París. Algunos de ellos optaron por presentar sus estudios del natural<br />

en los certámenes oficiales, junto a sus obras más acabadas.<br />

Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Bazille y Cézanne frecuentaron el bosque de Fontainebleau<br />

en la década de 1860, donde tomaron el relevo de la Escuela de<br />

Barbizon. Con ellos, el trabajo en el taller pasó a segundo plano, y la espontaneidad<br />

y la rapidez de ejecución que habían sido consustanciales de los<br />

estudios al aire libre se convirtieron en uno de los fundamentos de su pintura.<br />

De este modo, los estudios al aire libre —en su función tradicional de apoyo a<br />

la creación artística—, dejaron de tener sentido, pues ellos mismos pasaron a<br />

convertirse en el centro de la práctica artística. Pero la aparente libertad del<br />

trabajo del natural no tardó en convertirse en una traba a la creación plástica.<br />

Monet, quien en 1880 aseguraba no poseer otro estudio que la naturaleza,<br />

empezó por las mismas fechas a concluir sus obras en el taller.

for which he would be able to draw on visual memory rather than imagination.<br />

Whatever the case, open-air studies ultimately became restricted to<br />

the artist’s private working practice.<br />

During the first half of the 19th century, the clear-cut distinction between<br />

landscapes painted out-of-doors and those executed in the studio<br />

began to break down. From the 1820s there was a greater degree of crossover<br />

between the two methods with a more careful finish evident in open-air<br />

oils and the use of motifs taken from nature in studio compositions. Artists<br />

such as Corot and Constable extended the practice of painting directly from<br />

nature to their work as a whole and the fashion for oil studies of this kind soon<br />

swept across most of Europe and the United States. At the same time, such<br />

studies gained increasing recognition and independence, particularly among<br />

the Barbizon School artists (Rousseau, Diaz de la Peña, Dupré and Daubigny<br />

among others), who frequented the Forest of Fontainebleau, sixty kilometres<br />

south of Paris. Some of these painters entered studies taken directly from<br />

nature alongside other, more finished works at official exhibitions.<br />

In the 1860s, Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Bazille and Cézanne also began to<br />

frequent the Forest of Fontainebleau and subsequently took over from the<br />

artists of the Barbizon School. For these artists studio painting was secondary<br />

and the spontaneity and rapid execution hitherto characteristic of openair<br />

studies now became basic tenets of their art. In fact, those very studies<br />

made in the open air — at least the ones which traditionally served as aids<br />

to indoor production — became pointless since they themselves had become<br />

the focus of creative practice. Yet the apparent freedom inherent in working<br />

from nature was soon to become an obstacle to artistic creation. Indeed, in<br />

1880 Monet himself declared that he had no other studio than that of nature<br />

yet around that time he began finishing his paintings in his atelier.<br />

With the appearance of the avant-garde movements at the beginning<br />

of the 20th century, working in the studio regained lost ground vis-à-vis

A comienzos del siglo XX, con la eclosión de las vanguardias, el trabajo en<br />

el estudio volvió a ganar en importancia frente al trabajo al aire libre. En<br />

todo caso, entre los artistas que trabajaron en plena naturaleza predominó<br />

la vertiente expresionista que hacía del paisaje una proyección del los anhelos<br />

subjetivos del artista.<br />

En la muestra esta evolución se cuenta a través de siete salas dedicadas<br />

a otros tantos motivos enraizados en la tradición de la pintura al aire libre.<br />

Dichas salas temáticas reúnen escuelas artísticas y estilos distintos con el<br />

fin de mostrar tanto la continuidad de la tradición de la pintura al aire libre<br />

como sus cambios a lo largo de los años.<br />

working in the open air. However, prevalent among the plein-air painters<br />

was an Expressionist facet which turned landscape into a projection of the<br />

artist’s subjective desires.<br />

The development of open-air painting is explored in seven rooms dedicated<br />

to motifs deeply rooted in its tradition. In each thematic space different<br />

schools and styles are displayed with the aim of illustrating the continuity<br />

of the tradition of open-air painting and the changes which took place<br />

within it over time.<br />

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg<br />

El Coliseo, interior (detalle), 1813-1816<br />

Interior of the Coliseum (detail)<br />

Copenhague, Thorvaldsen Museum

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes<br />

Loggia en Roma: tejado en sombra, 1782-1784<br />

Loggia in Rome: Roof in the Shade<br />

París, Musée du Louvre.<br />

Colección del conde de l’Espine, donada por<br />

su hija, la princesa Louis de Croÿ, 1930<br />

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes<br />

Loggia en Roma: tejado al sol, 1782-1784<br />

Loggia in Rome: Roof in the Sun<br />

París, Musée du Louvre.<br />

Colección del conde de l’Espine, donada por<br />

su hija, la princesa Louis de Croÿ, 1930

RUINAS, AZOTEAS Y TEJADOS<br />

Las ruinas y arquitecturas constituían en el siglo XVIII uno de los elementos<br />

integrantes de la pintura de paisaje, al que otorgaban un carácter pintoresco.<br />

Como tales, fueron objeto de la atención de los jóvenes artistas que se<br />

formaron en Italia a finales de siglo y comienzos del siguiente, siguiendo la<br />

tradición del paisaje idealista del XVII y de las vedute del siglo XVIII. Ahora<br />

bien, en los estudios al aire libre ese pintoresquismo cedió terreno ante el<br />

afán de veracidad que perseguía, no tanto una estricta atención al detalle,<br />

sino la correcta plasmación del motivo en su conjunto, en sus formas y texturas,<br />

y en sus valores tonales.<br />

RUINS, TERRACES AND ROOFS<br />

In the 18th century, ruins and certain architectural features became key factors<br />

in landscape painting, endowing it with a picturesque character. Such<br />

features attracted the attention of young painters who trained in Italy in the<br />

late 18th and early 19th centuries, following the tradition of 17th-century<br />

idealist landscape and 18th-century vedute. In open-air studies this picturesque<br />

element was gradually abandoned in favour of a desire for veracity<br />

which pursued a correct representation of the motif as a whole with regard<br />

to forms, textures and tonal values rather than strict attention to detail.

ROCAS<br />

La representación de rocas está presente en la pintura de paisaje desde sus<br />

inicios. Los primeros estudios de roquedales fueron pintados en Italia a finales<br />

del siglo XVIII, pero el protagonismo de este motivo llegó de la mano<br />

de la Escuela de Barbizon; no en vano las formaciones rocosas del bosque<br />

de Fontainebleau ocupan aproximadamente un cuarto de su superficie. Los<br />

pintores de Barbizon les otorgaron valores melancólicos, de soledad y desolación.<br />

En el caso de los artistas americanos, por el contrario, arte y geología<br />

fueron de la mano. Hacia finales del siglo XIX, Cézanne retomó el motivo de<br />

las rocas para ahondar en la construcción espacial del cuadro sin recurrir al<br />

sombreado o la perspectiva.<br />

ROCKS<br />

Rocks appear in the earliest examples of landscape paintings. The first separate<br />

studies of rocks were painted in Italy in the late 18th century but it was<br />

the Barbizon School which made this motif a pre-eminent one, and it is not<br />

by chance that those painters chose to depict the Forest of Fontainebleau,<br />

where rock formations account for around a quarter of the surface area.<br />

These painters imbued their images with a sense of melancholy, solitude<br />

and devastation. In contrast, for American artists art and geology often went<br />

hand in hand. Towards the end of the 19th century Cézanne returned to the<br />

motif of rocks in order to analyse spatial construction without resorting to<br />

shading or perspective.

Paul Cézanne<br />

Peñascos en el bosque, c. 1893<br />

Forest with Boulders<br />

Zúrich, Kunsthaus,<br />

legado del Dr. Hans Schuler, 1920

Johann Wilhelm Schirmer<br />

Paisaje de Civitella, 1839<br />

Landscape near Civitella<br />

Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle<br />

Ferdinand Hodler<br />

El Niesen visto desde Heustrich, 1910<br />

Mount Niesen seen from Heustrich<br />

Basilea, Kunstmuseum Basel

MONTAÑAS<br />

Las montañas no fueron objeto de interés estético hasta el siglo XVIII. Entre<br />

los artistas que trabajaron en Italia predominan las imágenes alejadas, concebidas<br />

como fondos para la composición de cuadros en el estudio. Un caso<br />

excepcional fue el del Vesubio, objeto de numerosas representaciones. Fue<br />

en el centro de Europa donde la iconografía de las montañas alcanzó sus<br />

configuraciones más originales, a menudo a medio camino entre el idealismo<br />

romántico y el interés científico. Los estudios de montañas al aire libre<br />

se extendieron también a países como Austria, Francia o España. En la obra<br />

del pintor suizo Ferdinand Hodler, a comienzos del siglo XX, las montañas<br />

adoptan un carácter simbólico y monumental.<br />

MOUNTAINS<br />

Mountains did not become a subject of aesthetic interest until the 18th century.<br />

Most of the artists who worked in Italy produced distant views as backgrounds<br />

for their studio paintings, although one frequently depicted exception<br />

was Vesuvius. However, it was in central Europe that the iconography of<br />

mountains gave rise to the most original expressions, often mid-way between<br />

Romantic idealisation and scientific interest. Open-air studies of mountains<br />

were also produced in countries such as Austria, France and Spain. In the<br />

early 20th century, mountains took on a symbolic, monumental character<br />

in the work of the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler.

Théodore Rousseau<br />

Los grandes robles<br />

del viejo Bas-Bréau, 1864<br />

The Great Oaks of<br />

Old Bas-Bréau<br />

Houston, The Museum<br />

of Fine Arts. Adquisición<br />

del museo con fondos<br />

de la Agnes Cullen Arnold<br />

Endowment Fund<br />

ÁRBOLES Y PLANTAS<br />

En la Italia de finales del siglo XVIII se extendió la costumbre de ejecutar<br />

estudios del natural de los ejemplares más bellos y pintorescos de árboles y<br />

plantas. A ello se sumó el interés botánico puesto de moda por el naturalista<br />

sueco Linneo, y que se difundió con rapidez en los países anglosajones. Pero<br />

donde este tipo de estudios alcanzó mayor desarrollo fue en la Francia de<br />

comienzos del siglo XIX, merced a la preparación de las pruebas del Grand<br />

Prix de Rome de paysage historique, creado en 1817. Para los pintores de<br />

Barbizon, algo más tarde, los árboles se convirtieron en actores silenciosos<br />

del paisaje. A comienzos de la década de 1860 los impresionistas también<br />

pintaron árboles en el bosque Fontainebleau, pero frente al interés romántico<br />

por los sentimientos que desprenden los grandes robles y hayas, artistas<br />

como Monet se concentraron en las sensaciones visuales de la luz al filtrarse<br />

a través de sus hojas. Hacia finales del siglo XIX y comienzos del XX los estudios<br />

de árboles adoptaron un carácter esencialmente expresivo.

Claude Monet<br />

El roble Bodmer, bosque<br />

de Fontainebleau, 1865<br />

The Bodmer Oak,<br />

Fontainebleau Forest<br />

Nueva York, The<br />

Metropolitan Museum<br />

of Art, donación de<br />

Sam Salz y legado<br />

de Julia W. Emmons,<br />

por intercambio, 1964<br />

TREES AND PLANTS<br />

The practice of executing open-air studies of the finest and most picturesque<br />

trees and plants became widespread in late 18th-century Italy. Additionally,<br />

the work of the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus sparked an interest<br />

in botany that spread rapidly throughout the English-speaking world.<br />

However, it was in early 19th-century France that this type of study became<br />

widespread, as works entered for the Grand Prix de Rome de paysage<br />

historique, created in 1817, required a great deal of preparation. For<br />

the Barbizon painters, some years later, trees became silent protagonists<br />

of the landscape. In the early 1860s the Impressionists also painted trees<br />

in the Forest of Fontainebleau, but in contrast to the Romantic interest in<br />

the sentiments transmitted by great oaks and beeches, artists like Monet<br />

focused on the visual sensations of light as it filters through leaves. Studies<br />

of trees took on an essentially expressive character in the late 19th and<br />

early 20th centuries.

Camille Corot<br />

La cascada de Marmore, en Terni, c. 1826<br />

The Waterfall of the Marmore<br />

Roma, BNL BNP Paribas Group Collection

CASCADAS, LAGOS, ARROYOS Y RÍOS<br />

Desde el origen del género del paisaje, el agua contribuyó a imprimir variedad<br />

y frescura a los cuadros. Torrentes y saltos de agua aparecen ya en los<br />

estudios de enclaves próximos a Roma, como Tívoli o Terni, famosos por sus<br />

cascadas, o la región de los «Castelli Romani», con sus lagos Nemi y Albano,<br />

plasmados de forma sintética por los paisajistas neoclásicos. En Inglaterra,<br />

los estudios al óleo de ríos alcanzaron su punto culminante en la obra<br />

temprana de Turner y de Constable. El agua está también muy presente en<br />

la obra de Courbet —con un sentido muy material— y de Daubigny, quien introdujo<br />

el elemento acuático en la temática de la Escuela de Barbizon y se<br />

hizo construir un barco-estudio para pintar en él sus vistas de los ríos Sena<br />

y Oise. De entre los impresionistas, Monet fue el que mayor atención prestó<br />

a los efectos cambiantes del agua.<br />

WATERFALLS, LAKES, STREAMS AND RIVERS<br />

To add variety and freshness to the composition, even the earliest of landscape<br />

paintings featured water. Cascades and waterfalls appear in studies<br />

of locations near Rome such as Tivoli and Terni, famous for their cascades,<br />

and the region of the “Castelli Romani” with lakes Nemi and Albano, depicted<br />

in a synthetic manner by the Neo-classical landscape painters. In England,<br />

oil studies of rivers reached their high point in the early work of Turner and<br />

Constable. Water is also notably present in the paintings of Courbet — who<br />

gave it a particularly material feel — and of Daubigny who introduced it into<br />

the subject matter of the Barbizon School and had a studio-boat built, from<br />

which to paint views of the Seine and the Oise. Among the Impressionists it<br />

was Monet who paid most attention to the changing effects of water.

John Constable<br />

Tormenta de<br />

lluvia sobre el mar,<br />

c. 1824-1828<br />

Rainstorm over<br />

the Sea<br />

Londres, Royal<br />

Academy of Arts<br />

CIELOS Y NUBES<br />

La representación de los cielos atrajo la atención de los tratadistas desde<br />

tiempos de Leonardo. Sin embargo, fue en el siglo XVIII y comienzos del XIX<br />

cuando se extendió la costumbre de ejecutar estudios de nubes. Encontramos<br />

ejemplos de ellos entre los artistas franceses y alemanes que se formaron<br />

en Italia. Pero quien llevó a cabo un trabajo más sistemático en la<br />

observación de los cielos fue Constable. El artista inglés, en su intento de<br />

lograr una mayor integración entre cielo y paisaje en sus grandes composiciones,<br />

llegó a pintar más de cien estudios de nubes en sus dos principales<br />

campañas en Hampstead entre 1820 y 1822. Otro destacado pintor de<br />

cielos fue Boudin, quien influyó en artistas como Courbet y Monet. Ahora<br />

bien, entre los impresionistas fue Sisley quien concedió mayor relevancia a<br />

los cielos en su obra siguiendo el ejemplo de Constable. La sala se completa<br />

con cuadros de Van Gogh y Nolde, con una concepción estilizada, subjetiva<br />

y prácticamente abstracta de las nubes.

Eugène Boudin<br />

Estudio de cielo<br />

sobre la dársena<br />

del puerto comercial<br />

de El Havre,<br />

c. 1890-1895<br />

Study of the Sky<br />

over the Basin<br />

du Commerce at<br />

Le Havre<br />

El Havre, Musée<br />

d’art moderne André<br />

Malraux (MuMa)<br />

SKIES AND CLOUDS<br />

The depiction of the sky had been a subject of interest to art theoreticians<br />

since the time of Leonardo. However, it was in the 18th and early 19th centuries<br />

that the custom of executing cloud studies became widespread, and<br />

examples exist by French and German artists who trained in Italy. It was the<br />

English painter Constable, however, who undertook the most systematic observation<br />

of the heavens in his quest for a greater integration of sky and landscape<br />

in his major compositions. Indeed, he painted more than one hundred<br />

studies of clouds during his two principal painting campaigns in Hampstead<br />

between 1820 and 1822. Another important sky painter was Boudin, who<br />

influenced artists such as Courbet and Monet. Among the Impressionists,<br />

however, it was Sisley who conceded most importance to skies and clouds,<br />

following the example of Constable. This room concludes with works by Van<br />

Gogh and Nolde, whose paintings reflect a stylised, subjective and almost<br />

abstract conception of clouds.

Vincent van Gogh<br />

Paisaje bajo un cielo agitado, 1889<br />

Landscape under a Stormy Sky<br />

Martigny, cortesía Fondation Pierre<br />

Gianadda, Fondation Socindec

Emil Nolde<br />

Nubes de verano, 1913<br />

Summer Clouds<br />

Madrid, <strong>Museo</strong> <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong><br />

© Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Gustave Courbet<br />

La ola, c. 1869<br />

The Wave<br />

Edimburgo, Scottish<br />

National Gallery, donado<br />

por Sir Alexander<br />

Maitland en memoria de<br />

su esposa Rosalind, 1960<br />

EL MAR<br />

La exposición concluye con una sala dedicada al mar. Como la montaña, el<br />

mar fue contemplado con temor hasta el siglo XVIII. Si bien algunos pintores<br />

neoclásicos ejecutaron estudios de marinas al aire libre en la bahía de<br />

Nápoles, de nuevo fue Constable quien llevó a cabo las primeras marinas al<br />

aire libre importantes. La moda de las estancias en la playa como destino<br />

vacacional, de la que participó Constable, se extendió de Inglaterra al norte<br />

de Francia y, desde el segundo cuarto del siglo XIX se asistió a un progresivo<br />

descubrimiento del litoral de Normandía por parte de escritores y pintores.<br />

Ahí realizó Courbet sus «paisajes de mar», de una materialidad propia<br />

de las rocas de su región natal del Franco Condado. De entre los impresionistas<br />

fue Monet el que sintió mayor atracción por el mar; no en vano su<br />

juventud había transcurrido en la costa normanda. Allí realizó entre 1880<br />

y 1883 seis campañas en las que pintó el mar, el cielo y los acantilados, con<br />

distintos tipos de pincelada.

Claude Monet<br />

Mar agitado,<br />

Étretat, 1883<br />

Étretat, Rough Sea<br />

Lyon, Musée des<br />

Beaux-Arts<br />

THE SEA<br />

The exhibition ends with a room dedicated to the sea. Like mountains, the<br />

sea was viewed with fear until the 18th century. While some Neo-classical<br />

painters produced outdoor sea studies on the Bay of Naples, it was once<br />

again Constable who was responsible for the first important examples painted<br />

outdoors. The fashion for seaside holidays (shared by Constable) spread<br />

from England to northern France, and from the second quarter of the 19th<br />

century writers and painters began to discover the Normandy coast. This<br />

was also where Courbet executed his first “landscapes of the sea”, which<br />

have a material quality comparable to the rocks of his native region of the<br />

Franche-Comté. Among the Impressionists, Monet was particularly attracted<br />

to the sea; it is not by chance that he spent his youth on the Normandy<br />

coast, where he subsequently undertook six painting campaigns between<br />

1880 and 1883, during which he depicted cliffs, sea and sky in a variety of<br />

brushstroke techniques.

MUSEO<br />

THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA<br />

Paseo del Prado, 8<br />

28014 Madrid<br />

mtb@museothyssen.org<br />

www.museothyssen.org<br />

FECHAS<br />

Del 5 de febrero<br />

al 12 de mayo de 2013.<br />

LUGAR<br />

Sala de Exposiciones Temporales<br />

del <strong>Museo</strong> <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong>.<br />

HORARIO<br />

De martes a domingo, de 10:00<br />

a 19:00 h. Los sábados la exposición<br />

permanecerá abierta hasta las<br />

21:00 h. Lunes cerrado. Cerrado<br />

el día 1 de mayo. El desalojo de las<br />

salas de exposición tendrá lugar<br />

cinco minutos antes del cierre.<br />

VENTA DE ENTRADAS<br />

Aforo limitado. Para asegurarse<br />

el acceso a la exposición en el día y hora<br />

deseados, recomendamos adquirir las<br />

entradas anticipadamente.<br />

Venta anticipada:<br />

• Taquilla del <strong>Museo</strong><br />

• www.museothyssen.org<br />

• Teléfono: 902 760 511

TARIFAS<br />

TRANSPORTE<br />

• General:<br />

Colecciones <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong>:<br />

9,00 ¤<br />

Exposición Impresionismo<br />

y aire libre. De Corot a Van Gogh:<br />

10,00 ¤<br />

Entrada combinada para las<br />

Colecciones <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong><br />

y la exposición Impresionismo y aire<br />

libre. De Corot a Van Gogh: 15,00 ¤<br />

• Mayores de 65 años, pensionistas,<br />

estudiantes, titulares de Carné Joven,<br />

profesores de la Facultad de BB. AA.,<br />

ciudadanos con discapacidad superior<br />

al 33 y miembros de familia numerosa,<br />

previa acreditación: Colecciones<br />

<strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong>: 6,00 ¤<br />

Exposición Impresionismo y aire libre.<br />

De Corot a Van Gogh: 6,00 ¤<br />

Entrada combinada para las<br />

Colecciones <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong> y<br />

la exposición Impresionismo y aire libre.<br />

De Corot a Van Gogh: 8,00 ¤<br />

Metro: Banco de España.<br />

Autobuses: 1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 14, 15, 20, 27,<br />

34, 37, 45, 51, 52, 53, 74, 146 y 150.<br />

Tren: estaciones de Atocha, Sol y<br />

Recoletos.<br />

SERVICIO DE INFORMACIÓN<br />

Teléfono: 902 760 511<br />

cavthyssen@stendhal.com<br />

TIENDA-LIBRERÍA<br />

Planta baja. Catálogo de la exposición<br />

disponible.<br />

CAFETERÍA-RESTAURANTE<br />

Planta baja.<br />

SERVICIO DE AUDIO-GUÍA<br />

Disponible en español, inglés y francés.<br />

Se ruega no utilizar el teléfono móvil<br />

en las salas de exposición.<br />

• Gratuita: menores de 12 años<br />

acompañados y ciudadanos en<br />

situación legal de desempleo,<br />

previa acreditación.

MUSEO<br />

THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA<br />

Paseo del Prado, 8<br />

28014 Madrid<br />

mtb@museothyssen.org<br />

www.museothyssen.org<br />

DATES<br />

5 February to 12 May 2013.<br />

VENUE<br />

Temporary Exhibition Galleries,<br />

<strong>Museo</strong> <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong>.<br />

OPENING HOURS<br />

Tuesdays to Sundays, 10am to 7pm.<br />

The temporary exhibition will be<br />

opened until 9pm on Saturdays.<br />

Closed on Mondays. Closed 1 May.<br />

Visitors are asked to leave the galleries<br />

5 minutes before closing.<br />

TICKET SALES<br />

Limited entry numbers. Early booking<br />

is recommended to ensure entry<br />

for the chosen day and time.<br />

Pre-booked tickets:<br />

• At the Museum’s ticket desk<br />

• www.museothyssen.org<br />

• Tel: 902 760 511<br />

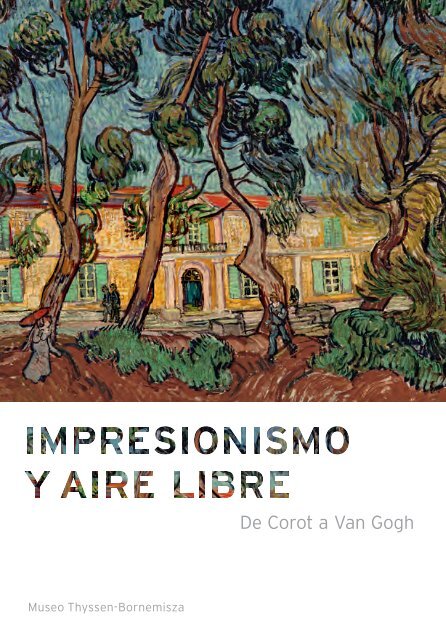

Cubierta / Front cover<br />

Vincent van Gogh<br />

El hospital de Saint-Rémy (detalle), 1889<br />

Hospital at Saint-Remy (detail)<br />

Los Ángeles, The Armand Hammer<br />

Collection, donación de la Armand Hammer<br />

Foundation, Hammer Museum<br />

Contra / Back cover<br />

Camille Corot<br />

La cascada de Marmore,<br />

en Terni (detalle), c. 1826<br />

The Waterfall of the Marmore (detail)<br />

Roma, BNL BNP Paribas<br />

Group Collection

TICKET PRICES<br />

TRANSPORT<br />

• General:<br />

<strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong> Collections:<br />

9,00 ¤<br />

Impressionism and Open-air Painting.<br />

From Corot to Van Gogh exhibition:<br />

10,00 ¤<br />

Combined ticket for<br />

<strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong> Collections<br />

and Impressionism and Open-air<br />

Painting. From Corot to Van Gogh<br />

exhibition: 15,00 ¤<br />

• Senior citizens (65 and over),<br />

pensioners, Carné Joven holders,<br />

Fine Arts teachers, students, Disabled<br />

with 33 rating and members of<br />

large families, with proof of status:<br />

<strong>Thyssen</strong>-<strong>Bornemisza</strong> Collections:<br />

6,00 ¤<br />

Impressionism and Open-air<br />

Painting. From Corot to Van Gogh<br />

exhibition: 6,00 ¤<br />

Combined ticket for <strong>Thyssen</strong>-<br />

<strong>Bornemisza</strong> Collections and<br />

Impressionism and Open-air Painting.<br />

From Corot to Van Gogh exhibition:<br />

8,00 ¤<br />

Metro: Banco de España.<br />

Buses: 1, 2, 5, 9, 10, 14, 15, 20, 27,<br />

34, 37, 45, 51, 52, 53, 74, 146 and 150.<br />

Train: Atocha, Sol and Recoletos<br />

stations.<br />

INFORMATION SERVICE<br />

Tel: 902 760 511<br />

cavthyssen@stendhal.com<br />

BOOKSHOP/GIFTSHOP<br />

Ground floor. Catalogue of<br />

the exhibition on sale.<br />

CAFETERIA-RESTAURANT<br />

Ground floor.<br />

AUDIO-GUIDE<br />

Available in Spanish, English<br />

and French.<br />

Mobile telephones must not be used<br />

in the exhibition rooms.<br />

• Free admission: Accompanied children<br />

under 12 and officially unemployed<br />

people.