old master drawings - Museum of Fine Arts - Florida State University

old master drawings - Museum of Fine Arts - Florida State University

old master drawings - Museum of Fine Arts - Florida State University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

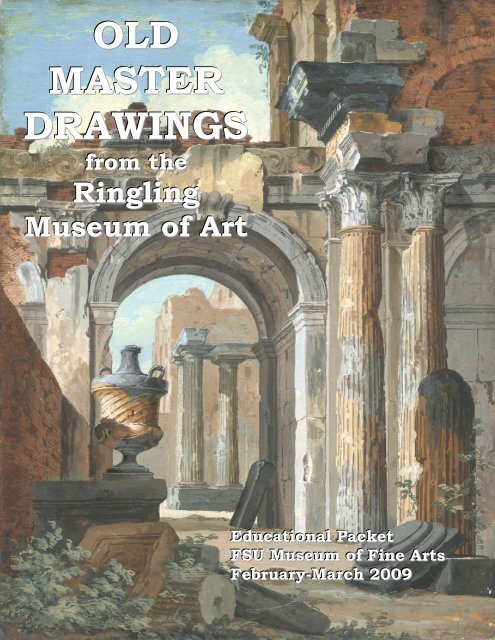

OLDMASTERDRAWINGSfrom theRingling<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtEducational PacketFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>February-March 2009

Old Master Drawings from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009IntroductionFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Education Packet

Letter to the EducatorsFebruary/March2009Dear Leon County Educators,We invite you and your students to visit the <strong>Florida</strong> <strong>State</strong><strong>University</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> (FSU MoFA) to experience Old Master Drawingsfrom the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art, an exhibition featuring many famous OldMasters. Throughout the duration <strong>of</strong> this show, during February and March <strong>of</strong>2009, we will have special tours and events. This packet is designed forteachers to use in the classroom to help students explore various ideas andthemes that are addressed. It is designed to give students a basic awareness <strong>of</strong>Old Masters’ <strong>drawings</strong> and their techniques. This packet is in accordance with<strong>Florida</strong>’s Sunshine <strong>State</strong> Standards, and we hope that it will be helpful to youin your classroom.Gina Caruso and JooHee Kang<strong>Museum</strong> Education Program<strong>Florida</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Introduction Page 2

Sunshine [Year] <strong>State</strong> StandardsVisual <strong>Arts</strong>February/March2009Pre K-2• The student uses two-dimensional and three-dimensional media,techniques, tools, and processes to depict works <strong>of</strong> art from personalexperiences, observation or imagination.• The student uses the elements <strong>of</strong> art and the principles <strong>of</strong> design toeffectively communicate ideas.• The student uses age-appropriate vocabulary to describe, analyze,interpret, and make judgments about works <strong>of</strong> art.3-5• The student uses the elements <strong>of</strong> art and the principles <strong>of</strong> design withsufficient manipulative skills, confidence, and sensitivity whencommunicating ideas.• The student develops and justifies criteria for the evaluation <strong>of</strong> visualworks <strong>of</strong> art using appropriate vocabulary.• The student knows the types <strong>of</strong> tasks performed by various artists andsome <strong>of</strong> the required training.6-8• The student understands what makes various organizational elementsand principles <strong>of</strong> design effective and ineffective in the communication <strong>of</strong>ideas.• The student knows and uses the interrelated elements <strong>of</strong> art and theprinciples <strong>of</strong> design to improve the communication <strong>of</strong> ideas.• The student understands and uses information from historical andcultural themes, trends, styles, periods <strong>of</strong> art, and artists.9-12• The student uses two-dimensional and three-dimensional media,techniques, tools, and processes to communicate an idea or conceptbased on research, environment, personal experience, observation, orimagination.• The student applies various subjects, symbols, and ideas in works <strong>of</strong> art.• The student understands how recognized artists recorded, affected, orinfluenced change in a historical, cultural, or religious context.Introduction Page 3

About: The John and Mable Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009The John and Mable Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art was establishedin 1927 in Sarasota, <strong>Florida</strong>. The museum, which is the legacy <strong>of</strong>John Ringling (1866-1936) and his wife, Mable (1875-1929), is the<strong>of</strong>ficial <strong>State</strong> Art <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Florida</strong>. Featured are 21 galleries <strong>of</strong>European paintings as well as Cypriot antiquities, Asian Art,American paintings, and contemporary art. Newly opened in 2007,the Ulla R. and Arthur F. Searing Wing serves as the travelingexhibition area <strong>of</strong> the museum.View <strong>of</strong> the Johnand MableRingling <strong>Museum</strong><strong>of</strong> Art, Sarasota,<strong>Florida</strong>.Although better known for its large-scale European paintings,the museum also h<strong>old</strong>s a collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>old</strong> <strong>master</strong> <strong>drawings</strong>.Comprised <strong>of</strong> unparalleled examples by well known artists, theexhibition is a significant accomplishment for the institution. TheOld Master Drawings spans three centuries, from the late 15 th to thelate 18 th , and has between 40 and 50 pieces. The highlight <strong>of</strong> thecollection, which is among the finest in the country, are works fromthe Baroque period <strong>of</strong> the 17 th century. The <strong>old</strong> <strong>master</strong> exhibitionexpresses the vast variety and invention <strong>of</strong> the Ringling’s works-onpaperwhich shows quality, scope <strong>of</strong> drawing media, technique, andgenre. This provides the museum’s visitors the valuableopportunity to understand the medium as well as the Ringling’spermanent collection as a whole.* Information borrowed from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> website (www.ringling.org) for educational purposes onlyIntroduction Page 4

Old Master Drawings from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009BackgroundInformationFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Education Packet

The History <strong>of</strong> DrawingFebruary/March2009“Drawing is going for a walk with a line” -Paul KleeHuman beings have always felt the need torepresent all that surrounds them in drawing. Thefirst <strong>drawings</strong> go back to the Superior Paleolithic,35,000 years ago, when Homo Sapiens representedtheir world on cave surfaces or on the skins <strong>of</strong>animals hunted. An example <strong>of</strong> this artisticmanifestation can be found in the cave paintings <strong>of</strong>Altamira, in Spain.Later, the Egyptiansknew how to utilizeUnknown, Magdalenian CavePainting <strong>of</strong> a Bison, 16,000-9,000 BC,Altamira, Spain.drawing to decorate the most imposingconstructions in history, the pyramids. Overthousands <strong>of</strong> years drawing had evolvedsubstantially. From the single-colored andsimple compositions <strong>of</strong> prehistory, new stridesbrought Egyptian balance, thoroughness, andcoloring to theological representations intemples and sanctuaries. There was a need todetail the figures <strong>of</strong> the mythological gods to thank them for the splendor <strong>of</strong> theEgyptian empire.Unknown, Funerary Papyrus (Osiris in DjedPillar & Nut in Tree), 1050-1000 BC, pigment onpapyrus, Egypt.In the sixth century BC, the Greeks achievedthe maximum balance in drawing. Hoping to presentcandid human expression, they removed ostentationfrom their imagery. They achieved their goal andobtained what was considered to be harmonicbalance.The Romans, 500 years later, contributeddiversity. An army and discipline were required tomaintain an empire over extensive territory and tosubdue many diverse culturesunder the same authority. ThatUnknown, Utrecht Psalter,820-835, ink on vellum orparchment, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Utrecht.Parthian Monument, reconstructeddrawing, Imperial(Roman) Ephesus,Turkey.facilitated, in some measure, the abandonment <strong>of</strong> pureornamentation. Instead, the Romans developed technicaldrawing which required specific technique and mathematicalknowledge.A greater number <strong>of</strong> complete works is preserved fromthe Middle Ages. During this period, vivaciousrepresentations prevailed. Line with and without color was incharge <strong>of</strong> producing form and detail. The Arab incursion intoEurope introduced a revolutionary support for <strong>drawings</strong>,paper as well as ink and pen.BackBackground Information Page 5-6

The History <strong>of</strong> DrawingFebruary/March2009Raphael, Study for TheAlba Madonna, 1505-08,pen and red chalk, Museesd’Art et d’ Historie, Lille,France.Giovanni Battista Tiepolo,1696-1770, Seated RiverGod, Nymph with Oar, andPutto, pen and brown ink,brush with pale and darkbrown wash, over blackchalk, The Metropolitan<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art, New York.The revival <strong>of</strong> interest in classical art and science, whichwe term the Renaissance, first appeared in fourteenth centuryItaly. In this period human anatomy was systematicallystudied and perspective was developed as part <strong>of</strong> theexpanding fields <strong>of</strong> science and art. Drawing becamevolumetric thanks to the new techniques <strong>of</strong> coloring. The use<strong>of</strong> light and shade, together with perspective, brought realismto drawing. The High Renaissance style <strong>of</strong> the late fifteenth andearly sixteenth century represented the culmination <strong>of</strong> theRenaissance period. In the High Renaissancethe forms became heavier and broadlymassed. Tones <strong>of</strong> dark and light replace theearlier more linear manner. Renaissance stylereceived its fullest expression in such <strong>master</strong>sas Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael,and Titian. In Germany, Albrecht Dürer wasthe first artist who began to view drawing asan independent art work.The Baroque stretched from theRenaissance to the 17th century. Itexaggeratedly used all the resourcescontributed by the Renaissance to express aAlberecht Dϋrer, BabaraDϋrer, 1514, pen and inkon paper, Erlangen,<strong>University</strong> Library.wide range <strong>of</strong> attitudes, from the calamity <strong>of</strong> poverty to thesplendor <strong>of</strong> wealth. Uniformity was broken in Baroque pictorialrepresentations to maximize attraction <strong>of</strong> the spectator.From the 20th century onwards the continual line <strong>of</strong>development that had followed the history <strong>of</strong> drawing wasbroken. Drawing forked into a multitude <strong>of</strong> styles:romanticism, realism, impressionism, expressionism, fauvism, cubism,futurism, and surrealism. Nevertheless, all these styles made use <strong>of</strong> what hadbeen contributed in the past to now express new approaches.Vincent Van Gogh, StarryNight, 1889, pen drawing,<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Architecture,Moscow.Henri Matisse, SleepingWoman, 1942, Besançon's<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> andArcheology, France.Pablo Picasso,Igor Stravinsky,1917, TheGrangerCollection, NewYork.Fedor Rusetsky,Give Us Our DailyBread…, 1931,watercolor, ink,photomontage.Eolo Pons, Espana Tell,1939, pencil drawing.BackBackground Information Page 5-6

Drawing TimelineFebruary/March2009From Cave Drawing to theRenaissance: 15,000 B.C.-A.D. 140031,000 B. C. Rhinoceroses, lions andmammoth featured onthe walls <strong>of</strong> theChauvet cave inSouthern France.3100 B. C. The Egyptians painted murals onthe walls <strong>of</strong> tombs, designed to help the occupation<strong>of</strong> the next world.700 B.C. Wonderful drawing inGreece and Rome in the form <strong>of</strong> vasedecoration.820-832 A graphic tradition <strong>of</strong>book illustration developed in the Middle Ages.The Renaissance in Italy:1300-16001400 Artists began to use studies <strong>of</strong> anatomyand the science <strong>of</strong> perspective.Baroque Drawing in Italy:1600-1800Material splendorand drama weredeveloped in the imageryas a means <strong>of</strong> givingphysical substance to therevived Catholic Churchand to the emergingmonarchies <strong>of</strong> Europe.Rococo: Art was noted for restraintand logic but with a discreetcounterbalancing <strong>of</strong> decorative andrealistic elements.Neo-Classicism, Romanticism,and Realism: 1800-1860Neo-Classicism: Drawing wasmarked by disciplinedobservation, refinedsensibilities andtechnical virtuosity.Jean-Auguste Ingre(1780-1867, French)Romanticism: Lines move freely todescribe movements and feelingsrather than visual studies.TheodreGericault(1791-1824,French)Ferndinand VictorEugene Delacrox(1798-1863,French)Realism: Art was influenced bylandscape artJohn Constable (1776-1837, English)Vincent Vahn Gogh (1853-1890,Dutch-French)Paul Gaugin (1848-1903, French)Georges Seurat(1859-1891, French)The Twentieth Century:Les Fauves, Cubism, andAbstractionCubism and PabloPicasso ( 1881-1973,Spanish- French)AbstractionLes Fauves andHenri Matisse(1869-1954, French)Twentieth-Century Expressionism:This style gave a forceful visualstatement to inner feeling (directcommunication <strong>of</strong> feeling).Renaissance and Baroque Drawing in Germany andthe Netherlands: 1400-1700Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441, Flemish)Pieter Brueghel (1525-1569, Flemish)Albercht Dürer (1471-1528, German)Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669, Dutch)Baroque and Rococo Drawing in Flanders,France, England, and Spain: 1600-1800Peter PaulRubens &AnthonyVan Dyck:Drawings wereknown for freedom <strong>of</strong>execution, b<strong>old</strong> contrast <strong>of</strong> value, and fluid andfacile draftsmanship.Impressionism andPostimpressionism: 1860-1900Claude Monet (1840-1926, French):The study was noted for a method<strong>of</strong> recreating the surface vitality <strong>of</strong>the image, a means to characterizeout-<strong>of</strong>-door light in nature.Edouard Manet (1832-1883, French)Edgar Degas (1834-1917, French)Paul Cezanne (1839-1906, French)Surrealism and Realism in theTwentieth Century:The surrealist penchant for aheightened imaginative atmosphereand organic forms has influencedmuch subsequent expression.Background Information Page 7

The History <strong>of</strong> Old Masters and their DrawingsFebruary/March2009The term Old Master is <strong>of</strong>ten used to describe a European painter <strong>of</strong> skillwho was born before the 19 th century. As time has passed, other importantartists born in the 1800s have also been considered Old Masters. In theory, anOld Master should be an artist who was fully trained, was a <strong>master</strong> <strong>of</strong> his localartists’ guild, and also worked independently. Old Master Drawings are soclassified mainly because <strong>of</strong> the medium and support employed, and the date<strong>of</strong> the work. The medium that was used most <strong>of</strong>ten was chalk, pen & ink,and/or brush & wash. Usually the works were supported by paper butsometimes vellum or parchment was used.Drawings <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters were not only admired for their beauty, butalso served as teaching tools and provided a means for studying the methodsand styles <strong>of</strong> the artists who changed the course <strong>of</strong> art. The sixteenth andseventeenth centuries were also a period when biographies <strong>of</strong> the greatRenaissance artists were being written by authors such as Vasari, Baldinucciand Van Mander. These biographies familiarized the public with the OldMasters and established them as admirable people who became the foundation<strong>of</strong> academic art. In the eighteenth century, recognition <strong>of</strong> their work wasbrought to a much wider audience with the development <strong>of</strong> new printingprocesses, such as engraving and mezzotint.The term “Old Master” tends to be avoided by art historians because <strong>of</strong>its vagueness. The terms Old Master prints and Old Master <strong>drawings</strong>,however, are still used and the designation remains more current in the arttrade. Drawings from the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, andnineteenth centuries seem <strong>old</strong> to us now and establishing a dividing linebetween the <strong>old</strong> and the modern becomes an increasingly difficult task. Evenso, issues <strong>of</strong> chronology and terminology aside, there are significant differencesbetween the materials and techniques <strong>of</strong> drawing from the nineteenth andtwentieth centuries as compared to ones from centuries up to 400 years earlier.Rembrandt, Saul with his Servants at the Fortune-teller <strong>of</strong> Endor,1657, drawing in bister and reed pen on paper with nowatermark, <strong>Museum</strong> Bredius, The Netherlands.Background Information Page 8

List <strong>of</strong> Most Famous Old MastersFebruary/March2009Refer to List <strong>of</strong> Famous Women Artists in packet for female Old Masters. Old Masters on this list were found on manyother “Famous Old Master Lists” and were born before the 19 th century. Giotto di Bondone (Italian, 1267-1337) Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519) Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528) Michelangelo (Italian, 1475-1564) Titian (Italian, c.1477-1576) Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520) Parmigianino (Italian, 1503-1540) Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594) Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Flemish, c.1525-1569) Paolo Veronese (Italian, c.1528-1588) El Greco (Greek, 1541-1614) Frans Hals (Dutch, 1580-1666) Caravaggio (Italian, 1573-1610) Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640) Nicolas Poussin (French, 1594-1665) Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660) Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669) Johannes Vermeer (Dutch, 1632-1675) Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721) Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (Italian, 1691-1770) Francois Boucher (French, 1703-1770) Joshua Reyn<strong>old</strong>s (English, 1723-1792) Jean-Honore Fragonard (French, 1732-1806) Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828) Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres (French, 1780-1867) Ivan Aivazovsky (Armenian, 1817-1900) Jean Leon Gerome (French, 1824-1904) Adolphe William Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905) Camille Pissarro (French, 1830-1903) Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch, 1836-1912) Paul Cezanne (French, 1839-1906) Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)Poussin, The Last Supper, oil oncanvas, 1640s, Belvoir Castle. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French , 1841-1919) Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925) Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918)Da Vinci, Mona Lisa,oil on poplar, 1503-1506, Louvre.Goya, Little Giants, oil on canvas,1791, Museo del Prado.Edgar Degas, Ballerinas in Romantic Tutus inLe Foyer de la Danse, oil on canvas, 1872,Musee d’Orsay.Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, oil oncanvas, 1889, <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Modern Art.Background Information Page 9

Historical Women in ArtFebruary/March2009Women have been involved in making art in most times and places,despite difficulties in training, trading their work, and gaining recognition.However, women artists have been excluded from participation inand popularization <strong>of</strong> the world <strong>of</strong> art by art historians and artcritics alike. So in the last few decades, historians have endeavoredto rediscover the artistic accomplishments <strong>of</strong> women and toincorporate them into art history.The studies <strong>of</strong> many early ethnographers and culturalanthropologists indicate that women were <strong>of</strong>ten the principleartisans in pre-history, creating their pottery, textiles, baskets, andjewelry. Also, some cave paintings bear the hand prints <strong>of</strong> womenas well as those <strong>of</strong> men. According to earliest historical records <strong>of</strong>Europe, there are a number <strong>of</strong> Greek women who were painterssuch as Timarete, Eirene, Kalypso, Aristarete, Iaia, and Olympus.In the Medieval era, women artists wereeither wealthy aristocratic women or nuns.Wealthy women <strong>of</strong>ten created embroideries and textiles,while nuns <strong>of</strong>ten produced illuminations.Artemisia Gentileschi, JudithBeheading Hol<strong>of</strong>ernes, 1612,Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.Hildegard <strong>of</strong> Bingen,Illumination from the LiberScivias, 12 th century.Until the Renaissance era, secular female artists didnot achieve international reputations. Along with the rise inHumanism, there was a shift away from art as a craft.While craftsmen required seven years <strong>of</strong> apprenticeship,artists were expected to have a solid arts training, alongwith knowledge in perspective, mathematics, ancient art,and study <strong>of</strong> the human body. Women, however, could notstudy the human body because it required working frommale nudes and corpses. Fortunately, many aristocraticwomen had access to some art training and the children <strong>of</strong>painters were able to gain training in their fathers’ workshops.Women artists in the Baroque era began to change the way women weredepicted in art. For example, in Judith Beheading Hol<strong>of</strong>ernes, ArtemesiaGentileschi depicted Judith as a strong woman determining her own destiny.Around 1600, still life emerged as animportant genre particularly in theNetherlands. Women were at the forefront <strong>of</strong>this painting genre because they could nottrain from nudes, but could access thematerials for still life. In other regions,women artists like Giovanna Garzonicreated realistic vegetable arrangements onparchment, and Louise Moillon was notedfor fruit still life paintings utilizing brilliantcolors.Josefa de Ayala, Still-life, 1679, oil on canvas,Satarem, Portugal, Municipla Library.Most academies were not open to women even by the eighteenth century.In the late eighteenth century, however, there were important steps forward forBackground Information Page 10-11

Historical Women in ArtFebruary/March2009women artists. In Paris, the Salon, the exhibition <strong>of</strong> workfounded by the Academy, became open to non-academicpainters in 1791, allowing women to showcase their work inthe powerful annual exhibition. In addition,women were more frequently accepted asstudents by famous artists, such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean Baptiste Greuze.In the beginning <strong>of</strong> the nineteenthcentury, women such as Marie Ellenrieder andMarie-Danise Villers worked in the field <strong>of</strong>portraiture and Rosa Bonheur excelled inMary Cassatt, Summertime,1894, oil on canvas.realistic painting, particularly <strong>of</strong> animals.Also, in this era, photography was a newmedium and several women like MargaretElisabeth Vigee-Lee Brun,Portrait <strong>of</strong> Marie-Antoinette,1783, oil on canvas.Carmeron and Gertrude Kasebier became well-known in thisfield. Later, in the 1860s and 1870s, manywomen became involved in the FrenchImpressionist Movement including Mary Cassatt and Lucy Bacon.The twentieth century shows an array <strong>of</strong> new movementsand rapid transitions. Georgia O’Keefe, one <strong>of</strong> the leading paintersin modernist art, was renowned for her works featuring flowers,bones, and landscapes <strong>of</strong> New Mexico. Maria Stanisia became one<strong>of</strong> the greatest painters in religious art by overcoming thepatriarchal attitudes both within early twentieth century Chicagoand the hierarchy <strong>of</strong> the Roman Catholic Church. There wereseveral noted women in Abstract Expressionism such as HelenFrankenthaler, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, and Jane Frank.In the Art Deco era, Hildreth Meiere, who is known for large-scaleDorothea Lange, Migrant Mother,1936, photography.Georgia O’Keefe, No.13Special, 1916-1917,charcoal on paper.mosaics, was honored with the <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> Medal <strong>of</strong> theAmerican Institute <strong>of</strong> Architects, a first for women. Womenalso made significant contributions to twentieth centuryphotography. Among these were Lee Miller for high fashionphotography, Dorothea Lange for documentaryphotography, and Margaret Bourke-White for industrialphotography. There were also art movements founded orco-founded by women: Constructivism, Cubo-Futurism,and Suprematism, by Aleksandra Ekster; Orphism byDelaunay; Color Field Movement by Helen Frankenthaler;the Society <strong>of</strong> Layerists by Mary Caroll Nelson; andFeminist art by Judy Chicago.Recently, women artists have been increasinglyprominent and their artistic accomplishments have beenrediscovered.Background Information Page 10-11

List <strong>of</strong> Famous Women ArtistsFebruary/March2009Women on this list include Old Masters and other famous artists all <strong>of</strong> whom can be found on many other lists.Ancient and Classical Periods Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun TimareteNineteenth Century Eirene Constance Mayer Kalypso Marie Ellenrieder Aristarete Rosa Bonheur Iaia Elizabeth Butler Olympias Berthe MorisotMedieval Era Mary Cassatt Ende Camille Claudel Diemudus Suzanne ValadonHildegard <strong>of</strong> Bingen, Guda Anna BochMotherhood from theBerthe Morisot, L- Claricia Lucy BaconSpirit and the Water,enfant au Tablier Herrade <strong>of</strong>Twentieth Century1165.Rouge, c. 1870.Landsberg Lee Bontecou Hildegard <strong>of</strong> Bingen Louise BourgeoisRenaissance Elizabeth Catlett Caterina dei Vigri Judy Chicago Maria Ormani Sonia Delaunay S<strong>of</strong>onisba Anguissola Dulah Marie Evans Lucia Anguissola Bracha L. Ettinger Lavinia Fontana Helen Barbara LonghiFrankenthaler Fede Galizia Françoise Gilot Natalia Goncharova Georgia O’Keefe, Ram’s Diana Scultori Ghisi Grace Hartigan Head White Hollyhock and Esther InglisS<strong>of</strong>onisba Eva HesseLittle Hills, 1935. Marietta RobustiAnguissola, Self Malvina H<strong>of</strong>fman(daughter <strong>of</strong> Tintoretto) Portrait, 1554. Lee Krasner Properzia de' Rossi Frida Kahlo Levina Teerlinc Barbara Kruger Catarina van Hemessen Tamara de LempickaBaroque Era Dora Maar Mary Beale Maruja Mallo Rosalba Carriera Agnes Martin Élisabeth Sophie Chéron Joan Mitchell Isabel de Cisneros Louise Nevelson Josefa de Óbidos Georgia O'Keeffe Giovanna Garzoni Verónica Ruiz de Artemisia GentileschiVelasco Judith Leyster Charlotte SalomonRachel Ruysch, Still- Maria Sibylla Merian Ángeles SantosLife with Bouquet <strong>of</strong> Louise Moillon Zinaida Serebriakova Tamara deFlowers and Plums, Maria van Oosterwijk Sr. Maria Stanisia Lempicka, Theoil on canvas, c. Clara Peeters Nellie WalkerMusician, 1929.1705. Luisa R<strong>old</strong>án known asTwenty-First CenturyLa R<strong>old</strong>ana Miranda July Rachel Ruysch Becca Bernstein Elisabetta Sirani Adrianne WortzelEighteenth Century Shahzia Sikander Giulia Lama Beth Stryker Anna DorotheaTherbusch Marie Watt Angelica Kauffmann Mary MoserAngelica Kauffmann, Maria CoswayLiterature and Anne Vallayer-Painting, 1782,CosterKenwood House. Adelaide Labille-Becca Bernstein, Donna,Guiard2007.Background Information Page 12

Old Master Drawings from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009ArtistBiographiesFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Education Packet

Francois Boucher(1703-1770)FrenchMore than any other artist, François Boucher(1703–1770) is associated with the formulation <strong>of</strong> themature Rococo style and its dissemination throughoutEurope. He worked in every medium and every genreand found wide reproduction in print form. He was alsohighly adept at marketing his work, providing designsfor all manner <strong>of</strong> decorative arts, from porcelain totapestry.For Boucher, <strong>drawings</strong> played a multitude <strong>of</strong>roles. They were important in the preparation <strong>of</strong>paintings and as designs for printmakers. They alsobecame finished works <strong>of</strong> art for the growing market <strong>of</strong>1collectors. For his major canvases, Boucher followedstandard studio practices <strong>of</strong> the time, working out theoverall composition and then making chalk studies for individual figures, orgroups <strong>of</strong> figures. Two Winged Putti, for example, is a study for a pair <strong>of</strong>Boucher's trademark dimpled putti in theforeground <strong>of</strong> Apollo Revealing His Divinity toIssé (1750). Oil and gouache sketches werecommon components <strong>of</strong> Boucher's workingprocess in the preparation <strong>of</strong> majorcommissions, although he increasingly madesketches as independent works.Boucher's delicate, lighthearteddepictions <strong>of</strong> classical divinities and welldressedFrench shepherdesses delighted thepublic. He was considered the mostFrancois Boucher, Boucherd’apres Lundberg, 174 ,oil on canvas, Louvre.fashionable painter <strong>of</strong> his day. Boucher'ssentimental, facile style was too widely imitatedand fell out <strong>of</strong> favor during the rise <strong>of</strong>neoclassicism.Francois Boucher, Two Winged Putti, 1748-50, Black chalk, brush and gray wash,heightened with white chalk, on beige paper,The Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Artist Biographies Page 13

Bernardino Campi(1522-1591)ItalianBernardino Campi (1522 - 1591) was anItalian Renaissance painter from Reggio Emilia, whoworked in Cremona. His father, Pietro Campi, washis first teacher and instructed the boy in his ownart, that <strong>of</strong> the g<strong>old</strong>smith. However, whenBernardino saw Titian's <strong>drawings</strong>, prints, anddesigns for tapestries, he at once abandoned thesculptural arts to study painting. He commencedpainting when nineteen years <strong>old</strong>, and soon excelledhis <strong>master</strong>s. Deeply impressed by the works <strong>of</strong>Correggio, Titian, Raphael, and Romano, heendeavored to unite all their merits into a style andestablished a standard <strong>of</strong> excellence. Afterward,Bernardino acquired his own style, painted excellent portraits, and decoratedS<strong>of</strong>onisba Anguissolo, BernardinoCampi Painting S<strong>of</strong>onisbaAnguissola, 1550s, oil on canvas,Siena.many <strong>of</strong> the Lombardy churches.His <strong>master</strong>piece is at Cremona in the cupola <strong>of</strong> S.Sigismondo. Here are depicted the multitude <strong>of</strong> saintsand the blessed, with their symbols. He finished thisprodigious composition, exhibiting great invention,variety, and harmony in seven months. He alsosuccessfully managed the drawing and perspective sothat the figures seem to be <strong>of</strong> natural size, whereas theyare ten feet high.In 1580 or 1584 at Cremona he published Pareresopra la pittura, a book full <strong>of</strong> valuable information forartists. Bernardino had many pupils, and this insuredhis influence on Italian art in the sixteenth century. Hewas the teacher <strong>of</strong> the first pr<strong>of</strong>essional women painter<strong>of</strong> the period, S<strong>of</strong>onisba Anguissola. Anguissola painteda portrait <strong>of</strong> Campi painting her portrait. Noteworthyamong his works are the Descent from the Cross in theBrera gallery at Milan, Mater Delorosa in the Louvre atParis, and the frescoes in the cupola <strong>of</strong> S. Sigismondoat Cremona.Bernardino Campi, The HolyFamily with St. Lucy, 1522-1591,pen and brown ink with brush andbrown wash heightened with whitegouache, The John and MableRingling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Artist Biographies Page 14

Jean-Honoré Fragonard(1732-11806)FrenchJean-Honoré Fragonard is a French painterwhose scenes <strong>of</strong> frivolity and gallantry are among themost complete embodiments <strong>of</strong> the Rococo spirit. Hewas a pupil <strong>of</strong> Boucher, before winning the Prix deRome in 1752. From 1756 to 1761 he was in Italy,where he tended to ignore the work <strong>of</strong> the approved<strong>master</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the High Renaissance, instead forming aparticular admiration for Tiepolo.He travelled and drew landscapes with HubertRobert and responded with special sensitivity to thegardens <strong>of</strong> the Villa d'Este at Tivoli, memories <strong>of</strong> whichoccur in paintings throughout his career. In 1765 hebecame a member <strong>of</strong> the Academy with his historicalpicture, Coroesus Sacrificing himself to Save Callirhoe (Louvre, Paris).Jean-Honoré Fragonard,Inspiration (Self-Portrait), 1769,oil on canvas, Louvre.He soon abandoned this style for thesecular canvases by which he is chieflyknown. After his marriage in 1769 he alsopainted children and family scenes. Hestopped exhibiting at the Salon in 1767 andalmost all <strong>of</strong> his work thereafter was donefor private patrons. Among them was Mmedu Barry, Louis XV's most beautifulmistress, for whom he painted the worksthat are <strong>of</strong>ten regarded as his <strong>master</strong>pieces- the four canvases representing TheProgress <strong>of</strong> Love (1771-73). These, however,were returned by Mme du Barry and itseems that taste was already turning against Fragonard's lighthearted style. Hetried unsuccessfully to adapt himself to the new neoclassical vogue, but inspite <strong>of</strong> the admiration and support <strong>of</strong> David he was ruined by the FrenchRevolution and died in poverty.Jean-Honore Fragonard, A Gathering at Wood’sEdge, 1760-80, red chalk, The Metropolitan<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Fragonard was a prolific painter, but he rarely dated his works so that itis not easy to chart his stylistic development. Nevertheless, alongside Boucher,his paintings seem to sum up an era. His delicate coloring, wittycharacterization, and spontaneous brushwork ensured that even his mostsecular subjects are never vulgar and his finest work has an irresistible verveand joyfulness.Artist Biographies Page 18

Angelica Kauffmann(1741-1807)SwissAngelica Kauffmann was born in Switzerland and grew up in Austria,where her family originated. Her father Johann was a poor man and amediocre painter but successfully taught Angelica to be an amazing painter.By the time she was 12, Angelica had completed aportrait <strong>of</strong> a bishop named Monsignor Nevroni, andshe started to make a name for herself. In 1754, herfather took her on a trip to Milan, a first <strong>of</strong> manytrips to Italy for Angelica. It was here in Italy whereAngelica became famous, especially for her portraits.Recognition <strong>of</strong> her accomplishments earned Angelicaelection into Rome’s Academy <strong>of</strong> St. Luke in 1765.In 1766, Angelica accompanied LadyWentworth to England, where her portraits became agreat success. She painted subjects, with inspirationfrom English romantic literature, for example, fromthe poetry <strong>of</strong> Alexander Pope. She also did a fewAngelica Kauffman, Self-Portrait,1780-85, oil on canvas, TheHermitage, St. Petersburg,until 1781 and became the first woman inEngland to be admitted to the Royal Academy,an institution for the advancement <strong>of</strong> art. In1781 she married for the second time andreturned to Italy with her husband.classical paintings such as scenes from Homer’sOdyssey. Angelicalived in LondonFrom 1781-1807, Angelica lived andworked in Rome in the most famous studio inthe city which was also a meeting place forpoets, artists, and thinkers <strong>of</strong> the day. After atrip to Venice in 1781, Angelica painted one <strong>of</strong>her most famous works, Leonardo da Vincidying in the Arms <strong>of</strong> Francis I. This was Angelica Kauffmann, Juno Borrowing theCestus <strong>of</strong> Venus, 1776-1777, drawing,followed by many more works with theJohn and Mable Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong>academy and her last exhibit was in 1797. Art.Angelica died in Rome in 1807 and washonored with a grand funeral directed by prominent sculptor Antonio Canova,who based it on the funeral <strong>of</strong> Raphael, in which the entire Academy <strong>of</strong> St.Luke and many people <strong>of</strong> the clergy attended.Artist Biographies Page 16

Charles-Joseph Natoire(1700-1777)FrenchGustaf Lundberg, Portrait <strong>of</strong>Charles- Joseph Natoire, Louvre.Charles-Joseph Natoire is a French painter <strong>of</strong>the Rococo, a period with a fancy style but lessgrandiose than the Baroque. He was born in Nîmes,France. There he was trained in the fundamentals<strong>of</strong> drawing by his father, who was a sculptor.At the age <strong>of</strong> seventeen he went to Paris andapprenticed under Louis Galloche. He thenattended the Royal Academy <strong>of</strong> Painting andSculpture. However, it was not until hisapprenticeship with François Lemoyne that hedeveloped an interest in anatomy.In 1721, Natoire’s artwork Sacrifice <strong>of</strong>Manoah to Obtain a Son won the Prix de Rome, anelite scholarship that provided travel to the Italiancity. During Natoire’s studies at the French Academyin Rome he received several commissions fromuding the French Ambassador. He also won first prizeimportant patrons inclfrom the Accademia di San Luca for his work Moses Returning from Sinai.In 1730, he returned to Paris. Four years later he was a full member <strong>of</strong>the Royal Academy <strong>of</strong> Painting and Sculpture. He spent nine years working onone commission, from the Director-General <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> theHouseh<strong>old</strong> <strong>of</strong> the King, providing paintings for the Chateau de La Chapelle-Godefroy, an estate in the French countryside. In the late 1730s he workedwith other artists like Francois Boucher to restore the Hotel de Soubise, amansion in Paris which today is the <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> French History. In 1751, hereturned to Italy and became the director <strong>of</strong> the French Academy in Romewhere he taught students who became well-known artists, such as HubertRobert and Jean-Honore Fragonard.Charles-Jospeh Natiore, Gardens <strong>of</strong> the Villa d'Este at Tivoli,watercolor, The Metropolitan <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Artist Biographies Page 17

Jaccapo Palma il Giovane(1544-1628)VenetianJaccapo Palma il Giovane, the great-nephew <strong>of</strong> il Vecchio, was one <strong>of</strong> thelast great high Renaissance painters in Venice, Italy. He was born in the cityand died there, so he was easily caught up in the fast paced artistic world thatsurrounded him in his hometown. In his father’s workshop, this Venetiantaught himself how to paint simply by observing. It is easily said that Palma ilGiovane is an underrated artist, over-shadowed by thegreat artists Tintoretto, Titian, and his great uncle, butwhen one looks at his works, s/he knows he was a one<strong>of</strong>-a-kindpainter. He was constantly painting, and in factmany believed he was obsessed with the art. Hisbiographer once reported “when his wife died, he beganto paint and when the women returned from the funeral,Jaccopo Palma il Giovane,he asked them whether they had accommodated her well.” Susanna Before Daniel, oilon canvas, 146.1 x 196.5The native Venetian, Palma il Giovane, was a truecm, Robert Simon <strong>Fine</strong> Art.Renaissance man, and he loved painting.When Palma il Giovane and the Duke <strong>of</strong> Urbino became acquainted in1567, the Duke sent the artist to Rome to apprentice for four years; that is t<strong>of</strong>ormally study. Palma il Giovane worked with Titian and Tintoretto, completingsome <strong>of</strong> their works, but was not given much credit for it. His great uncleJaccapo Negreti Palma il Giovane, or il Vecchio, completely trumped his greatnephew’sworks. The younger artist spent his whole life trying to compete withhis uncle, but he only came close to the <strong>master</strong>y <strong>of</strong> il Vecchio.When the Doge’s Palace burned in 1577 Palma il Giovane was asked toreplace and redecorate after the devastating fire. He was asked for threecanvases for the ceiling <strong>of</strong> the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. He was also asked topaint in the great council hall, and this commissionwas very exciting for the artist.By the mid-1580s, Palma il Giovane hadincorporated Tintoretto's versatile figure postures aswell as Titian's thick surfaces, emphasis on light,and loose brushstroke. After Tintoretto died in1594, Palma il Giovane became Venice’s dominantartist receiving many commissions. After Titan diedin 1576, Palma il Giovane completed the elderartist’s Pieta. Palma il Giovane also took intoconsideration the patron’s taste, <strong>of</strong>ten varying thestyle or degree <strong>of</strong> exaggeration as well as subjectJaccapo Palma il Giovane, Study matter to please his customers.<strong>of</strong> a Saint, black and white chalkIn the later years <strong>of</strong> his life Palma il Giovaneon blue paper, 27 x 17.9 cm,Katrin Bellinger Kunsthandel didn’t paint as much and lost some <strong>of</strong> his interestfor a wide range <strong>of</strong> commissions. After 1600 hepainted scenes <strong>of</strong> mythology for a small group <strong>of</strong> intellectuals. Jaccapo Palma ilGiovane, although not as well known as a number <strong>of</strong> the Renaissance artists,<strong>of</strong>fers today’s art lovers an interesting story and a legacy <strong>of</strong> his own.Artist Biographies Page 18

Elisabetta Sirani(1638-1665)ItalianEven though she only lived for 27 years, Elisabetta Sirani was a verysuccessful Baroque painter with over 200 paintings, <strong>drawings</strong>, and etchings.She was born in Bologna, Italy in 1638 to anartistic father Giovanni Sirani. Elisabetta wasan independent painter by 19 and ran herfamily’s workshop. When her father becamesick, she had to support her parents and herthree siblings entirely through her art.Elisabetta spent her short life in the city<strong>of</strong> Bologna which is a city famous for itsprogressive outlook toward women’s rights andfor generating flourishing female artists.Elisabetta became known very quickly for herart because <strong>of</strong> how fast she was able to finishpaintings. Her admirers liked to visit herstudio frequently to watch her work. Herpaintings focused on portraits, mythologicalsubjects, and, most famously, the Holy Familyand the Virgin and Child. Her works wereattained by wealthy, noble, and royal patrons.In 1665, Elisabetta became depressedElisabetta Sirani, Self-Portrait,unknown date, black and red chalk onpaper, Private Collection, Geneva,stomach ailment. Her father suspectedthat she had been poisoned by a jealousmaid and had the maid put on trial. Anautopsy showed that Elisabetta died fromstomach ulcers so the maid was acquitted.The city <strong>of</strong> Bologna honored Elisabettawith an elaborate public funeral thatincluded formal orations, special poetryand music, and a life-sized sculpture <strong>of</strong>her.and underweight. She forced herself to continueworking but within a few months she died <strong>of</strong> anundiagnosedElisabetta Sirani, Virgin and Child, 1663, oil oncanvas, National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Women in the <strong>Arts</strong>.Artist Biographies Page 19

Benjamin West(1738-1820)AmericanBenjamin West, Self Portrait, 1776, oilon canvas, currently at Baltimore<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> Art.Benjamin West, an American-born painter<strong>of</strong> historical, religious, and mythological subjects,had an influence on the development <strong>of</strong> historicalpainting in Britain. He was born in Springfield,Pennsylvania and was self taught. From 1746-1759 he painted portraits in Philadelphia. Whilein Philadelphia, Benjamin painted Death <strong>of</strong>Socrates which has been called “the mostambitious and interesting painting produced incolonial America.” After spending the first 20years <strong>of</strong> his life in Philadelphia, Benjamin movedto New York City and in 1760 he sailed to Italy.Being the first American artist to study in Italy,he embraced the neoclassical movementdeveloping all over the country. Benjamin visitedmost <strong>of</strong> the leading art cities <strong>of</strong> Italy and in 1763he moved to London to set up as a portraitpainter.While in England, King George III appointed Benjamin to the RoyalAcademy and commissioned him to create portraits <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> the royalfamily. While at the Academy, Benjamin painted his most famous works,including The Death <strong>of</strong> General Wolfe. At the time, this piece was verycontroversial because it broke the usual tradition <strong>of</strong> depicting s<strong>old</strong>iers inclassical costumes. He also painted Penn’s Treaty with the Indians in 1772 andDeath on a Pale Horse in 1817 both <strong>of</strong> which anticipated developments inFrench romantic painting.Benjamin died in 1820. He left not only a legacy <strong>of</strong> his strong historicalworks but also a following <strong>of</strong> painters who represented his training and counselthrough the nineteenth century.Benjamin West, The Death <strong>of</strong> General Wolfe, 1770, oil on canvas,National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Canada.Artist Biographies Page 20

Old Master Drawings from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009Lesson PlansFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Education Packet

Lesson Plan #1: Mona Lisa in the MillenniumFebruary/March2009Session Activity: After visiting the Old Master exhibition at the <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong><strong>Arts</strong>, students will focus on portraits that are featured in the show. Students willalso learn about Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Students will create their ownmodern day versions <strong>of</strong> a famous portrait choosing from Leonardo da Vinci’s MonaLisa, Girolamo Romanino’s Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Man, Ottavio Leoni’s Cardinal Francescodel Monte, Ippolito Leoni’s Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Lady, or Esias van de Velde’s Head <strong>of</strong> aCavalier.Da Vinci, Mona Lisa,1503-1506, oil onpoplar, Louvre.Esias van de Velde, Head <strong>of</strong> aCavalier, 1600s, black andwhite chalk over brush andgray wash, Ringling <strong>Museum</strong>.Grade Level: Upper elementary to high schoolTime Needed: one to four class periodsObjectives:1. To recreate a portrait <strong>of</strong> a famous work <strong>of</strong> art as it would look in modernday times.2. To appreciate and recognize that art reflects the time in which it is created.Materials:• A print <strong>of</strong> the Mona Lisa and the provided image CD with Old Masterportraits on it• 12” x 18” construction paper• Paint or colored pencilsVocabulary:1. Renaissance - the cultural rebirth that occurred in Europe from roughly thefourteenth through the middle <strong>of</strong> the seventeenth centuries, based on theemphasis <strong>of</strong> ideas, philosophies, art, and literature <strong>of</strong> Greece and Rome.During the Renaissance, America was discovered, and the Reformationbegan; modern times are <strong>of</strong>ten considered to have begun with theRenaissance. Major figures <strong>of</strong> the Renaissance include Galileo, WilliamShakespeare, Queen Elizabeth I, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo.Renaissance means “rebirth” or “reawakening.”2. Portrait - a verbal or visual picture or description, especially <strong>of</strong> a person.3. Sfumato - the blurring or s<strong>of</strong>tening <strong>of</strong> sharp outlines in painting by subtleand gradual blending <strong>of</strong> one tone into another.Lesson Plans Pages 21-22

Lesson Plan #1: Mona Lisa in the MillenniumFebruary/March20094. Wash - a thin layer <strong>of</strong> color applied by constant movement <strong>of</strong> the brush.Activity Procedures:1. Show a Mona Lisa print and the CD with the other Old Master images.Discuss the lifestyles <strong>of</strong> people who lived many centuries ago. What did theydo for fun without electricity, technology, and sufficient transportation?Compare and contrast the differences in contemporary and past timeperiods which might have affected the Mona Lisa and the other portraits.For example, the subject being painted couldn’t listen to an iPod or watch amovie to keep her/him entertained while the artist painted. Artists wouldsometimes hire musicians to play instead.2. Discuss artistic characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Mona Lisa and Old Master portraits.For example, the Mona Lisa is painted in s<strong>of</strong>t colors and everything appearsto be seen through a slight haze (this technique is called sfumato and iscaused by the blurring <strong>of</strong> outlines). The Old Master drawing, Head <strong>of</strong> aCavalier, is created with the use <strong>of</strong> grey wash with black and white chalk ontop <strong>of</strong> the wash.3. Have the students brainstorm ideas they could use to make a figure in an<strong>old</strong> portrait look as if she/he lived in today’s society. Some examples are: abeach in the background; sunglasses; a Disney World background; Mickeyears; a NYC background; a cell phone; a McDonald’s background; a Big Macin hand.4. Have students use paint or colored pencils to create their updated 21 stcentury versions <strong>of</strong> a Mona Lisa or Old Master portrait. Make sure to tellstudents to include the use <strong>of</strong> sfumato or grey wash with chalk.Evaluation: Did the student…1. Participate in discussion?2. Use sfumato or grey wash and chalk?3. Create a modern feeling through use <strong>of</strong> materials and images in theirportrait?Gioconda 2001. Robert Baron.http://www.studiolo.org/Mona/Gallery/MONAGAL05.htmGodzilla Meets MonaLisa. Ralph Arlyck.http://www.canyoncinema.com/A/Arlyck_GozillaMonaLisa.JPGFashionable Mona Lisa.http://www.canyoncinema.com/A/Arlyck_GozillaMonaLisa.JPGLesson Plans Pages 21-22

Lesson [Year] Plan #2: Value Lesson PlanFebruary/March2009Session Activity: Students will learn about value in drawing and expressvalue on prepared worksheets.Level: 4-5th gradeTime needed for Lesson: one-hour sessionObjective: Students will be able to talk about the value <strong>of</strong> their <strong>drawings</strong>. Eachwill complete a worksheet by creating shades or tints with chalk.Materials: Chalk and worksheets providedVocabulary:Value: Value is how dark or light something looks. We achievevalue changes in color by adding black or white to the color.Tint: a variation <strong>of</strong> a color produced by adding white to itand characterized by a low saturation with relatively highlightness.Shade: a color produced by a pigment or dye mixturehaving some black in it.*Chiaroscuro: Light-dark contrasts, pictorialrepresentation in terms <strong>of</strong> light and shade without regard to color.Procedure:1. Look at the <strong>old</strong> <strong>master</strong> <strong>drawings</strong> and discuss them. For each ask thefollowing questions:o What do you see?o What colors do you see?o Which parts are dark or light?o How did the artist make some parts dark or some parts light in thedrawing?o Why do you think the artist makes these parts dark or light?‣ Three-dimensional effects can be achieved by a contrast <strong>of</strong> darkand light.2. Experience the media, chalk:o Explain the usage and characteristics <strong>of</strong> chalks.Lesson Plans Page 23-26

Lesson [Year] Plan #2: Value Lesson Plano Let students use chalk freely (draw lines or fill the space withchalk). Ask:February/March2009‣ If you smudge the line, what happens?‣ What would you do, if you want to change something?‣ Can you express lightness or darkness with chalk? How?o Give students worksheet#1 that guides the creation <strong>of</strong> five-steps invalue with chalks.3. Give them worksheet#2 which has outlined shapes without color.o The teacher might set up a very simple still life with the sameobjects. Teachers can spotlight the objects so students can see thelights and darks as they draw, filling in the outline.4. Ask students which parts will be dark or light.5. Each student will finish the drawing begun in the outline by addingvalues using chalks.Evaluation: Students should be able to define value. Also, they should be ableto express value with chalk. They should be asked to answer the followingquestions about their <strong>drawings</strong>:1. Why do you make parts darker/lighter than others?2. What is the difference when you add value to a shape?Lesson Plans Page 23-26

Lesson [Year] Plan #2: Worksheet 1February/March2009LighterDarkerLesson Plans Page 23-26

Lesson [Year] Plan #2: Worksheet 2February/March2009Lesson Plans Page 23-26

Lesson Plan #3: Line: The Flexible Element <strong>of</strong> DesignFebruary/March2009Session Activity: After viewing the <strong>drawings</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters, students willlearn about line as an element <strong>of</strong> artistic design. They will learn whensketching or drawing that sometimes “less is more,” and only a few lines arerequired. The human eye and imagination can fill in the rest <strong>of</strong> the figure orobject. Give the students the worksheet included in the packet. Ask thestudents to draw things with which they are familiar utilizing those lines whileadding as few lines as possible.Francois Boucher, Hercules andOmphale with Cupirs, 1703-1770,red chalk and graphite, 12 5/8 in x10 ¼ in, Ringing <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Grade Level: Upper elementary through high school as a simple activity tolearn about line.Time Needed: one class period.Objectives:1. To have students draw objects or figures from just a few lines.2. To have students understand how the element <strong>of</strong> line can be used toconstruct an image.3. To show how the Old Masters sometimes used an economy <strong>of</strong> line.Materials:• Pencil• Worksheet withVocabulary:red lines1. Line - the path traced by a moving point. The most flexible and revealingelement <strong>of</strong> design.2. Old Master - a European painter <strong>of</strong> skill who was born before the 19 thcentury.Lesson Plans Pages 27-29

Lesson Plan #3: Line: The Flexible Element <strong>of</strong> DesignFebruary/March2009Activity Procedures:1. Discuss the <strong>drawings</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters and show slides to the students.2. Describe the way the lines give enough form to a figure or object for theeye to fill in the rest.3. Give several images on which you would like for them to focus. Selectimages from the CD numbered 6, 8, 9, 13, 17, 22, 25, 37, 40, or 44.4. Give students the worksheets with a few red lines on them (to show thedrawn starting point <strong>of</strong> the figures or objects) and have them create<strong>drawings</strong> in pencil using these lines. Remind students that these linescould be transformed into anything.5. Encourage students, if finished early, to create atmospheres orenvironments for the figures or objects using as few lines as possible.6. After the <strong>drawings</strong> are completed, have students show and explain to theclass how they created the figures or objects in the <strong>drawings</strong>. Stories areencouraged.Evaluation: Did the student…1. Participate in learning about line?2. Draw a figure or object?3. Draw a figure or object appropriately using as few lines as possible withthe economy <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters?Jan Cornelisz, Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Man, 1500-1559, red chalk, 8 15/16 x 5 5/16 in,Ringing <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.Leonardo Scaglia, Drawing for ArchitecturalOrnamentation, c. 1640, pen and brown ink withbrush and brown and grey wash, 5 7/8 x 8 ½ in,Ringing <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art.These two <strong>drawings</strong> are great examples <strong>of</strong> the economy <strong>of</strong> line. In the drawingon the right, even though the trees are rendered with minimal lines a full, threedimensional, finished effect is created. The man’s beard in the drawing on theleft emerges with only a few smudged lines.Lesson Plans Pages 27-29

Lesson Plan #3: WorksheetFebruary/March2009In the Style <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters: An Economy <strong>of</strong> LineAfter looking at the <strong>drawings</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Old Masters and observing the sparseness<strong>of</strong> this element <strong>of</strong> design, with a pencil draw figures or objects from the redlines given. Use an economy <strong>of</strong> line like the Old Masters.Lesson Plans Page 27-29

Lesson [Year] Plan #4: Composition and BalanceFebruary/March2009Session Activity: Students will learn about balance in relation to composition.Each student will construct a collage incorporating the concept <strong>of</strong> balance incomposition.http://www.jupiterimages.com/itemDetail.aspx?itemID=22850729Level: Upper elementary through high schoolTime needed for Lesson: one class periodObjective: Students will be able to talk about the balance <strong>of</strong> a work <strong>of</strong> art.They will also be able to talk about the balance used in works by the OldMasters. Each student will construct a collage incorporating balance <strong>of</strong>composition.Materials:• Construction paper (assorted colors)• Construction paper cutout shapes (assorted colors)• GlueVocabulary:1. Balance - When the eye is attracted equally to the various parts <strong>of</strong> acomposition. The sizes <strong>of</strong> shapes and strong contrasts <strong>of</strong> color contributeto a work’s “visual weight.” For example, a small dot <strong>of</strong> color or an area <strong>of</strong>deep shade has more visual weight than a field <strong>of</strong> gray or a highlight,respectively.2. Formal balance - Arrangement <strong>of</strong> a composition with one well-definedfigure placed centrally and with balancing elements placed on either side<strong>of</strong> this center.Lesson Plans Page 30-32

Lesson [Year] Plan #4: Composition and BalanceFebruary/March20093. Informal balance - The opposite <strong>of</strong> formal balance. Figures are notcentralized; they may be crowded around the edge or simply <strong>of</strong>f to a side.Procedures:1. Look at the Old Master <strong>drawings</strong> and discuss the following questions:• What do you see?• Does the work look balanced?• What type <strong>of</strong> balance (formal or informal) is used?• How do the positions <strong>of</strong> the figurescontribute to the balance?• Is there a central figure or area?• Does it contribute to the worksbalance?• Do the three figures form one largecentral figure?Angelica Kauffmann, Juno Borrowing theCestus <strong>of</strong> Venus , 1731-1807, pen andblack ink, 6 5/8 x 6 5/8 in.• How do the figures’ shapescontribute to the work’s balance?• Do the figures overlap?• Does that affect the balance <strong>of</strong> thecomposition?• Does the overlapping give thecomposition a circular feel?Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Deposition <strong>of</strong>Christ, 1548- 1628, pen and brownink, 11 x 9 in.• Is there positive ornegative space?• How does the use <strong>of</strong>negative and/or positivespace affect the balance<strong>of</strong> the composition?• How do the composition’slines affect the balance?Lesson Plans Page 30-32

Lesson [Year] Plan #4: Composition and BalanceFebruary/March20092.Unknown, Landscape with a Horseman,17 th century, pen and brown ink, 7 ¼ x 915/16. 2. Experience the medium: paper.• Explain the available shapes and color <strong>of</strong> paper.• Let students explore the possibilities <strong>of</strong> the paper. Are there contrasting colors? What happens if they overlap? What different shapes are available? What can you do with straight or curved edges? What happens if you leave blank space?3. Give students sheets <strong>of</strong> paper and various shapes.4. Students will construct collages.5. Each student will present his/her collage to the class explaining thechoices made to create balance. Students will identify whether or notthey used formal or informal balance.Evaluation: Students were able to discuss and define balance in their artworkand recognize the type <strong>of</strong> balance used.Lesson Plans Page 30-32

Suggestions <strong>of</strong> other Activities for Art TeachersFebruary/March2009Before and AfterGrade Level: 3-12The day the students go to the museum, pass out instruction sheets and three pieces <strong>of</strong>illustration board per person, each the size <strong>of</strong> 3X5 cards that can fit in their pockets.Each student will pick one painting in the museum. On the first card, the student willreproduce the artwork. On the second card the student will draw what was happeningbefore the painting was painted. On the last card, the student will draw what happenedafter the painting was created. After returning to the classroom, students will write thestory <strong>of</strong> what they think is happening in the original painting and then what ishappening in the before and after paintings.Portrait CollageGrade Level: 5-12Add a twist to the “Mona Lisa Lesson Plan.” Have students bring in found objects (fromhome, nature, or even from a store) to turn their portraits into collages. Instead <strong>of</strong>having students do portraits on construction paper, foam or cardboard would workbetter. This idea can utilize objects and paint or can utilize only objects and no paint.Examples will give students an idea <strong>of</strong> what is expected.Posing as an Old MasterGrade Level: 4-6Have students each choose a favorite artist from the Old Master <strong>drawings</strong> exhibition toresearch. Next the student will write a short summary on the basic facts about theartist’s life. Give each student a stretched canvas. Students will also research the use<strong>of</strong> canvas. They will discover the period it came into broad use, how it was made, andhow it was prepared by artists before painting. Students will do paintings in the style<strong>of</strong> the artists researched.Greek-Roman MythGrade Level: 5Students will look at the Old Master <strong>drawings</strong> which focus on Greek-Roman myths.Student will talk about the stories. As a class, they will read one myth selecting scenesto draw. Let the class divide into four or five groups. Each group will discuss a differentscene and pose like characters in the myth. Before drawing, each scene will bephotographed. They will draw the scenes as a group. The final illustrations <strong>of</strong> the mythwill be presented to the class.Portrait DrawingsGrade Level: 2-12Students will look at portraits in the exhibition. They will answer the followingquestions as a group about the portraits. 1) Is there any person you want to meet? 2)What is the character <strong>of</strong> that person? 3) What did you see in the portrait that made youthink <strong>of</strong> this person’s character? 4) If you could meet and interview these people, whatwould you ask them? 5) Do you know anyone today who is like any <strong>of</strong> the people in theportraits? 6) What is the reason the Old Master artist produced these portraits? 7) Whydo we produce portraits today?Space in DrawingGrade Level: 4-12Introduce the horizon line and refer to Giovanni Francesco Grimaldi’s The Cascatelleand Jean-Honore Fragonard’s The Vaulted Garden for reference. Students will discussforeground, background, and middle ground. They will talk about the differencebetween closer objects and distant objects. Closer objects are darker and lower on thepaper or lighter and lower dependent on the drawing. Then, they will demonstrate use<strong>of</strong> the horizon line, foreground, middle ground, background, and dark and light (value)to create a sense <strong>of</strong> space by drawing trees from the class window.Lesson Plans Page 33

Old Master Drawings from the Ringling <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> ArtFebruary/March2009ReferencesFSU <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>Education Packet

GlossaryFebruary/March2009~ Academy- a group <strong>of</strong> authorities and leaders in a field <strong>of</strong> scholarship,art, etc. who are <strong>of</strong>ten permitted to dictate standards, prescribe methods,and criticize new ideas.~ Art Deco- a decorative and architectural style <strong>of</strong> the period 1925-1940,characterized by geometric designs, b<strong>old</strong> colors, and the use <strong>of</strong> plasticand glass.~ Baroque- a style <strong>of</strong> architecture and art originating in Italy in the early17th century, characterized by classical orders and ornament, by formsin elevation and plan suggesting movement, and by dramatic effect inwhich architecture, painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts <strong>of</strong>tenworked to combined effect.~ Chiaroscuro- light-dark contrasts, pictorial representation in terms <strong>of</strong>light and shade without regard to color.~ Constructivism- a movement in modern art originating in Moscow,Russia in 1920 and characterized by the use <strong>of</strong> industrial materials suchas glass, sheet metal, and plastic to create nonrepresentational, <strong>of</strong>tengeometric objects.~ Cubo-Futurist- works that combine the Cubist usage <strong>of</strong> forms with theFuturist interest in dynamism.~ Cubism- a style <strong>of</strong> painting and sculpture developed in the early 20thcentury, characterized chiefly by an emphasis on formal structure, thereduction <strong>of</strong> natural forms to their geometrical equivalents, and theorganization <strong>of</strong> the planes <strong>of</strong> a represented object arranged independently<strong>of</strong> representational requirements.~ Ethnographers- a branch <strong>of</strong> anthropology dealing with the scientificdescription <strong>of</strong> individual cultures.~ Expressionism- a style <strong>of</strong> art developed in the 20th century,characterized chiefly by heavy, <strong>of</strong>ten black lines that define forms,sharply contrasting, <strong>of</strong>ten vivid colors, and subjective or symbolictreatment <strong>of</strong> thematic material.~ Fauvism- any <strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> French artists <strong>of</strong> the early 20th centurywhose works are characterized chiefly by the use <strong>of</strong> vivid colors inimmediate juxtaposition and contours usually in marked contrast to thecolor <strong>of</strong> the area defined.~ Gouache- a technique <strong>of</strong> painting with opaque watercolors prepared withgum.~ Humanism- a cultural and intellectual movement <strong>of</strong> the Renaissancethat emphasized secular concerns as a result <strong>of</strong> the rediscovery andstudy <strong>of</strong> the literature, art, and civilization <strong>of</strong> ancient Greece and Rome.~ Impressionism- a style <strong>of</strong> painting that seeks to re-create the artist's orviewer's general impression <strong>of</strong> a scene and is characterized by indistinctoutlines and by small brushstrokes <strong>of</strong> different colors.~ Mezzotint- a method <strong>of</strong> engraving a copper or steel plate by scrapingand burnishing areas to produce effects <strong>of</strong> light and shadow.~ Neoclassicism- the European movement which began after ca. 1765, asa reaction against both the surviving Baroque and Rococo styles, and asGlossary Page 34-35

GlossaryFebruary/March2009a desire to return to the perceived "purity" <strong>of</strong> the arts <strong>of</strong> Rome, the morevague perception ("ideal") <strong>of</strong> Ancient Greek arts (where almost no westernartist had actually been) and, to a lesser extent, 16th centuryRenaissance Classicism.~ Post-impressionism- a varied development <strong>of</strong> Impressionism by a group<strong>of</strong> painters chiefly between 1880 and 1900 stressing formal structure, aswith Cézanne and Seurat, or the expressive possibilities <strong>of</strong> form andcolor, as with Van Gogh and Gauguin.~ Putti- a representation <strong>of</strong> a small child, <strong>of</strong>ten unclothed and havingwings, used especially in the art <strong>of</strong> the European Renaissance.~ Renaissance- the cultural rebirth that occurred in Europe from roughlythe fourteenth through the middle <strong>of</strong> the seventeenth centuries, based onthe emphasis <strong>of</strong> ideas, philosophies, art, and literature <strong>of</strong> Greece andRome. During the Renaissance, America was discovered, and theReformation began; modern times are <strong>of</strong>ten considered to have begunwith the Renaissance. Major figures <strong>of</strong> the Renaissance include Galileo,William Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth I, Leonardo da Vinci, andMichelangelo. Renaissance means “rebirth” or “reawakening.”~ Rococo- a style <strong>of</strong> art, especially architecture and decorative art, thatoriginated in France in the early 18th century and is marked byelaborate ornamentation, as with a pr<strong>of</strong>usion <strong>of</strong> scrolls, foliage, andanimal forms.~ Romanticism- a movement in art originating in Europe in the late 18 thcentury that stressed personal emotion, free play <strong>of</strong> the imagination, andfreedom from rules <strong>of</strong> form.~ Sfumato- the blurring or s<strong>of</strong>tening <strong>of</strong> sharp outlines in painting bysubtle and gradual blending <strong>of</strong> one tone into another.~ Suprematism- a nonrepresentational style <strong>of</strong> art developed in Russia inthe early 20th century, characterized by severely simple geometricshapes or forms and an extremely limited palette.~ Surrealism- a style <strong>of</strong> art and literature developed principally in the 20thcentury, stressing the subconscious or nonrational significance <strong>of</strong>imagery arrived at by automatism or the exploitation <strong>of</strong> chance effects,unexpected juxtapositions, etc.~ Vellum- a heavy creamy-colored paper resembling parchment sometimesmade from calfskin, lambskin, or kidskin.Glossary Page 34-35

Exhibition Artist and Image ListFebruary/March20091. Ambrogio Bergognone, Italian (1453-1523)St. Augustine Liberating through a Window a Man Imprisoned by the Wicked Tyrant <strong>of</strong>PaviaPen and brown ink and brush and brown wash with white gouache. 8 15/16 x 9 13/16in.2. Girolamo Romanino, Italian (1484/7-1560)Portrait <strong>of</strong> a ManBlack chalk. 8 x 13/16 x 6 11/16 in.3. Giulio Romano, Italian (1499-1546)A BullPen and brown ink with brush and brown wash. 7 x 9 ¼ in.4. Giulio Romano, Italian (1499-1546)Head <strong>of</strong> St. Joseph, Study for Nativity with SS Longinus and JohnBlack chalk heightened with white chalk over brush and brown wash. 15 7/8 x 113/16 in.5. Bernardino Campi, Italian (1522-1591)The Holy Family with St. LucyPen and brown ink with brush and brown wash heightened with white gouache. 1411/16 x 9 13/16 in.6. Luca Cambiaso, Italian (1527-1585)Drawing for an Altarpiece <strong>of</strong> St. Sebastian with Two Attendant SaintsPen and brown ink with brush and brown wash. 21 3/8 x 13 13/16 in.7. Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Italian (1548-1628)Tarquinus and LucretiaPen and brown ink with brush and brown wash, heightened with white gouache,framing lines in black ink. 11 x 9 in.8. Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Italian (1548-1628)Deposition <strong>of</strong> Christ.Pen and brown ink with brush and brown wash over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 5 ½ x 6 ¼ in.9. Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Italian (1548-1628)Studies for a Resurrected ChristPen and brown ink. 11 5/8 x 8 ¼ in.10. Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Italian (1548-1628)Head <strong>of</strong> St. DamianBlack chalk heightened with white chalk (recto), pen and brown ink (verso). 8 5/8 x 63/3 in.11. Ottavio Leoni, Italian (1578-1630)Cardinal Francesco del MonteBlack chalk heightened with white on blue paper. 9 x 6 ½ in.12. Pietro Novelli, Italian (1603-1647)Design for a Mirror FramePen and brown ink with brush and brown and grey wash. 10 ¾ x 10 ½ in.13. Jan Cornelisz, Dutch (1500-1559)Exhibition Artist and Image List Page 36-39

Exhibition Artist and Image ListFebruary/March2009Portrait <strong>of</strong> a ManRed chalk. 8 15/16 x 5 5/16 in.14. Joachim Antonisz Wtewael, Dutch (1566-1638)The Decapitated St. John the BaptistPen and ink and brown wash. 7 5/8 x 6 ½.15. Bartholomaeus Spranger, Flemish (1546-1611)Banquet <strong>of</strong> OlympusPen and black ink with brush and blue wash. 13 ¼ x 9 5/16 in.16. Pieter Claesz Soutman, Flemish (1580-1657)Saint James the ElderGrisaille. 15 ¾ x 13 5/8 in.17. Unknown, Italian (16 th Century)Chariot Drawn by GriffonsPen and brown ink with brown and grey wash. 8 ¼ x 11 ¼ in.18. Imitator <strong>of</strong> Guercino, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, Italian (1591-1666)Portrait <strong>of</strong> a NoblemanPen and brown ink. 9 ½ x 7 ½ in.19. Giovanni Francesco Grimaldi, Italian (1606-1680)The CascatellePen and brown ink over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 7 ½ x 11 5/8 in.20. Ippolito Leoni, Italian (1627-1673)Portrait <strong>of</strong> a LadyBlack and white chalk. 5 13/16 x 4 ¼ in.21. Elisabetta Sirani, Italian (1638-1666)Venus and AnchisesBrush and brown wash over black chalk with traces <strong>of</strong> white chalk. 13 ¼ x 11 in.22. Leonardo Scaglia, Italian (active c. 1640)Drawing for Architectural OrnamentiationPen and brown ink with brush and brown and grey wash. 5 7/8 x 8 ½ in.23. Marco Ricci, Italian (1676-1730)Ruined Tomb in a LandscapePen and brown and black ink with brush and brown and grey wash with white gouache.15 3/16 x 21 3/16 in.24. Marco Ricci, Italian (1676-1730)Roman Architectural Ruins with Large ArchwayGouache over traces <strong>of</strong> black pen. 12 ¼ x 8 ½ in.25. Gerband van den Eckhout, Dutch (1621-1674)St. Peter Healing the LamePen and brown ink with brush and brown wash (recto), graphite (verso). 5 ¾ x 7 in.26. Esias van de Velde, Dutch (1591-1630)Head <strong>of</strong> a CavalierBlack and white chalk over brush and gray wash. 16 ¼ x 13 ¼ in.Exhibition Artist and Image List Page 36-39

Exhibition Artist and Image ListFebruary/March200927. Jan Fyt, Flemish (1611-1661)Study for a HoundBlack chalk. 7 5/16 x 13 ¼ in.28. Charles de la Fosse, French (1636-1716)Study <strong>of</strong> Three Male NudesRed chalk with traces <strong>of</strong> black chalk. 9 ½ x 15 in.29. Louis de Boullogne, French (1654-1733)Diana and EndymoinGouache on paper. 7 7/8 x 13 1/8 in.30. Unknown, Italian (17 th century)Landscape with a HorsemanPen and brown ink. 7 ¼ x 9 15/16 in.31. Gaetano Gandolfi, Italian (1734-1802)Study <strong>of</strong> a Seated Man H<strong>old</strong>ing a Sphere in Right HandRed chalk. 16 ½ x 11 ½ in.32. Francesco Navone, Italian (active c. 1770)Design <strong>of</strong> a Palatial GardenPen and brown ink with watercolor. 12 ¾ x 17 5/8 in.33. Unknown, Italian (18 th century)Design for a FountainPen and brown ink with brush and grey wash over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 11 5/8 x 8 in.34. School <strong>of</strong> Bibiena, Italian (18 th century)Interior <strong>of</strong> a Great HallPen and brown ink with brush and brown wash over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 19 ¾ x 26 ¼ in.35. Domenico Fabroni, Italian (active 1783-1805)Vaulted Two-Storied HallPen and black ink with brush and black wash and watercolor, heightened with whitegouache. 13 5/8 x 17 13/16 in.36. Giandomenico Tiepolo, Italian (1727-1804)Flying Cherubs on Clouds.Pen and brown ink with brush and brown and grey wash over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 7 ½ x11 3/16 in.37. Jean-Baptiste Oudry, French (1686-1755)Interior <strong>of</strong> a Theater with Spectators.Pen and black ink with brush and black wash, heightened with white gouache. 12 5/8x 18 ¼ in.38. Charles-Joseph Natoire, French (1700-1777)BacchusRed chalk with traces <strong>of</strong> white chalk. 14 ¾ x 11 ¾ in.39. Francois Boucher, French (1703-1770)Two PuttiRed and black chalk. 13 5/8 x 3 15/16 in.Exhibition Artist and Image List Page 36-39

Exhibition Artist and Image ListFebruary/March200940. Francois Boucher, French (1703-1770)Hercules and Omphale with Cupirs (recto), Designs for a Ceiling Decoration (verso)Red chalk (recto), red chalk and graphite (verso). 12 5/8 x 10 ¼ in.41. Carle Vanloo, French (1705-1765)Venus and Cupid IPen and black ink over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 5 5/8 x 9 in.42. Carle Vanloo, French (1705-1765)Venus and Cupid IIPen and black ink over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 5 5/8 x 5 5/8 in.43. Jean-Honore Frangonard, French (1732-1806)The Vaulted GardenBlack chalk. 8 1/8 x 11 5/16 in.44. Angelica Kauffmann, Swiss (1731-1807)Juno Borrowing the Cestus <strong>of</strong> VenusPen and black ink with brush and grey wash over traces <strong>of</strong> graphite. 6 5/8 x 6 5/8 in.45. Benjamin West, American (1738-1820)Study <strong>of</strong> a ChildBlack, red, and white chalk. 11 5/8 x 9 ¼ in.46. Unknown, (18 th century)Design for a Stage SettingPen and brown ink with brush and grey wash and watercolor. 21 x 12 ¾ in.47. Unknown, (18 th century)Fantastic Architecture (recto); Obelisk in Landscape (verso)Pen and brown ink. 5 7/8 x 9 ½ in.Exhibition Artist and Image List Page 36-39