Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

Issue 23 - W<strong>in</strong>ter 2012<br />

ISSN 1756-9575<br />

<strong>Market<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi – Eat Me Tender / Barbara J. Phillips – Advertis<strong>in</strong>g and the Cultural Mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> / Adele Tiengo and Leonardo Caffo –<br />

Animal Subjects: Local Exploitation, Slow Kill<strong>in</strong>g / Claire Molloy – Remediat<strong>in</strong>g Cows and the Construction <strong>of</strong> Ethical Landscape / Concepcion Cortes Zulueta – His<br />

Master’s Voice / Cluny South – <strong>The</strong> Tiger <strong>in</strong> the Tank / Iwan rhys Morus – Bovril by Electrocution / Louise Squire – <strong>The</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> Are “Break<strong>in</strong>g Out”! / Gene Gable –<br />

Can You Say, “Awww”? / Sonja Britz – Evolution and Design / Hilda Kean – Nervous Dogs Need Adm<strong>in</strong>, Son! / Kather<strong>in</strong>e Bennet – A Stony Field / John Miller -- Brooke’s<br />

1<br />

Monkey Brand Soap / Sunsan Nance – Jumbo: A Capitalist Creation Story / Kelly Enright – None Tougher / L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong> and Joe Zammit-Lucia – From Animal Rights and<br />

Shock Advocacy to K<strong>in</strong>ship With <strong>Animals</strong> / Natalie Gilbert – Fad <strong>of</strong> the Year / Jeremy Smallwood and Pam Mufson by Chris Hunter – <strong>The</strong> Saddest Show on Earth /<br />

Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti – Happy Easter / Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter – <strong>Animals</strong> on the Runway / Susan Nance – ‘Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration’ Posters / Emma Power -- Kill ‘em dead!”<br />

the Ord<strong>in</strong>ary Practices <strong>of</strong> Pest Control <strong>in</strong> the Home

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Culture</strong><br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Academic Board<br />

Steve Baker<br />

Ron Broglio<br />

Matthew Brower<br />

Eric Brown<br />

Carol Gigliotti<br />

Donna Haraway<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong><br />

Susan McHugh<br />

Rachel Poliqu<strong>in</strong><br />

Annie Potts<br />

Ken R<strong>in</strong>aldo<br />

Jessica Ullrich<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Bergit Arends<br />

Rod Bennison<br />

Helen Bullard<br />

Claude d’Anthenaise<br />

Petra Lange-Berndt<br />

Lisa Brown<br />

Rikke Hansen<br />

Chris Hunter<br />

Karen Knorr<br />

Rosemarie McGoldrick<br />

Susan Nance<br />

Andrea Roe<br />

David Rothenberg<br />

Nigel Rothfels<br />

Angela S<strong>in</strong>ger<br />

Mark Wilson & Bryndís Snaebjornsdottir<br />

Global Contributors<br />

João Bento & Catar<strong>in</strong>a Fontoura<br />

Sonja Britz<br />

Tim Chamberla<strong>in</strong><br />

Concepción Cortes<br />

Lucy Davis<br />

Amy Fletcher<br />

Katja Kynast<br />

Christ<strong>in</strong>e Marran<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Parra<br />

Zoe Peled<br />

Julien Salaud<br />

Paul Thomas<br />

Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti<br />

Johanna Willenfelt<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Maia Wentrup<br />

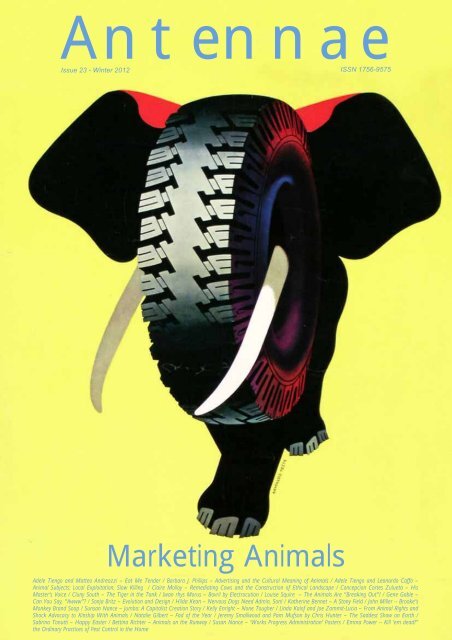

Front Cover Image: Orig<strong>in</strong>al image - Pirelli, Atlante, 1954 © Pirelli<br />

2

EDITORIAL<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 23<br />

T<br />

his issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong> was developed around the idea that advertis<strong>in</strong>g can be much more than<br />

a pivotal market<strong>in</strong>g tool <strong>in</strong> capitalist societies. Over the past few years, through the <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

popularity <strong>of</strong> social networks advertis<strong>in</strong>g strategies have more and more come to play a pivotal<br />

role <strong>in</strong> communication and can be understood as a cultural thermometer <strong>of</strong> our identities and desires.<br />

<strong>The</strong> conspicuous presence <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g is therefore a phenomenon that deserves study; it<br />

is not a new phenomenon <strong>in</strong> itself but it is one that nonetheless demands renewed attention and<br />

scrut<strong>in</strong>y through a human-animal studies lens. Whether photographed, illustrated, animated or filmed<br />

the ambivalent presence <strong>of</strong> the animal, <strong>in</strong>itially seems to facilitate the delivery <strong>of</strong> consumeristic<br />

messages. However, th<strong>in</strong>gs are much more complex. What does the animal sell to us and what do we<br />

effectively buy through these <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> visual consumption? What role does the animal play <strong>in</strong> the<br />

persuasions processes enacted by advertisements?<br />

In the attempt to provide some answers to these questions and more, besides a traditional call<br />

for academic papers, <strong>Antennae</strong> also solicited short commentaries on advertisements chosen by our<br />

readers and contributors. <strong>The</strong> colourful variety <strong>of</strong> examples submitted contributes to the outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an<br />

extremely diverse range <strong>of</strong> animal appearances <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g greatly vary<strong>in</strong>g on the grounds <strong>of</strong> what is<br />

to be sold and which target audiences are to persuade. <strong>The</strong>se shorter entries have been <strong>in</strong>terposed<br />

between longer and more complex analyses <strong>of</strong> specific animal presences <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unexpected result gathered from the collection <strong>of</strong> the excellent submissions we received, highlights a<br />

perhaps not too surpris<strong>in</strong>g, current, overrid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest for mammals aga<strong>in</strong>st any other animal group.<br />

Anthropomorphism may be an <strong>in</strong>evitable expedient essential to the success <strong>of</strong> the identification<br />

process ly<strong>in</strong>g at the core <strong>of</strong> all advertis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tend<strong>in</strong>g to sell us commodities. This is rather well<br />

demonstrated through the publication <strong>of</strong> a portfolio <strong>of</strong> v<strong>in</strong>tage adverts with which this issue comes to a<br />

close. For this essential contribution we have to thank Nigel Rothfels who on a warm June afternoon <strong>in</strong><br />

2011 walk<strong>in</strong>g lazily around the streets <strong>of</strong> Zurich came across a very unusual archive. As Nigel recalls, “I<br />

was <strong>in</strong> the city to attend a small conference on science and before long, I found myself star<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the w<strong>in</strong>dows <strong>of</strong> the Swiss National Bank! A quite fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g exhibit had been organized <strong>in</strong> the w<strong>in</strong>dows<br />

by staff at the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich focus<strong>in</strong>g on the history <strong>of</strong> animals appear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

posters. I went from w<strong>in</strong>dow to w<strong>in</strong>dow enjoy<strong>in</strong>g the posters and tak<strong>in</strong>g pictures. Through the generosity<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dr. Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter and Allesia Cont<strong>in</strong> at the Museum, we are now able to br<strong>in</strong>g a selection <strong>of</strong> this<br />

rarely seen and remarkable collection to <strong>Antennae</strong>’s readers”.<br />

Besides consider<strong>in</strong>g a range <strong>of</strong> well known and lesser know advertisements, this issue also looks<br />

at the more ethically driven consideration <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> animal imagery <strong>in</strong> the advertisements<br />

produced by animal advocacy and conservation organisations through a thought-provok<strong>in</strong>g piece by<br />

Joe Zammit-Lucia and L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong>, whilst an <strong>in</strong>terview with creative teams at Young & Rubicam<br />

Chicago demonstrates how the presence <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g can be used to the advantage <strong>of</strong><br />

animals through some astonish<strong>in</strong>gly simple but impressive communicational <strong>in</strong>ventiveness.<br />

Lastly I would like to take the opportunity to thank all <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this issue <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Antennae</strong>.<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong> Project<br />

3

CONTENTS<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 23<br />

6 Eat Me Tender<br />

Love can be dangerous when it comes to cook<strong>in</strong>g. In this image, the evidence that a ‘lover’ wants to possess his woman just like a ‘meat lover’ wants to eat his steak is<br />

exposed <strong>in</strong> a grotesque way. Sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation and animal exploitation are here associated to ‘love’, understood as an abuse mitigated by tenderness and care <strong>in</strong> the act<br />

<strong>of</strong> possess<strong>in</strong>g and kill<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi<br />

9 Advertis<strong>in</strong>g and the Cultural Mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Animals</strong><br />

One explanation for the proliferation <strong>of</strong> animal trade characters <strong>in</strong> current advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice proposes that they are effective communication tools because they can be used<br />

to transfer desirable cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs to products with which they are associated. <strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what messages these animals communicate is to explore the<br />

common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that they embody. This paper presents a qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the common themes found <strong>in</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> four animal characters. In<br />

addition, it demonstrates a method by which cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs can be elicited. <strong>The</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> this method for advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice are discussed.<br />

Text by Barbara J. Phillips<br />

20 Animal Subjects: Local Exploitation, Slow Kill<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>The</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Milan will host Expo 2015, with the theme “Feed<strong>in</strong>g the Planet. Energy for Life”. In view <strong>of</strong> this occasion, the <strong>in</strong>terest for cul<strong>in</strong>ary tradition and the global challenge<br />

<strong>of</strong> food security is rapidly grow<strong>in</strong>g. Farm<strong>in</strong>g and livestock rais<strong>in</strong>g traditions plays a major role <strong>in</strong> Italy, homeland <strong>of</strong> the worldwide renowned Slow Food.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Leonardo Caffo<br />

23 Remediat<strong>in</strong>g Cows and the Construction <strong>of</strong> Ethical Landscape<br />

Concern about the impact <strong>of</strong> livestock on the environment has generated debates about how best to manage dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g practices. Soil erosion and compaction and loss <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity from graz<strong>in</strong>g and silage production, ammonia and methane emissions, as well as high levels <strong>of</strong> water consumption, have all been identified as direct effects on the<br />

environment from dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g activity. [i] Whilst the issues have been well reported <strong>in</strong> the press, there has been little <strong>in</strong> the way <strong>of</strong> imagery to accompany the environmental<br />

critique <strong>of</strong> milk production. Instead, much <strong>of</strong> the popularly available imagery <strong>of</strong> dairy farm<strong>in</strong>g has been generated by advertis<strong>in</strong>g which cont<strong>in</strong>ues to deploy culturally-specific<br />

visions <strong>of</strong> contented cows <strong>in</strong> rural landscapes.<br />

Text by Claire Molloy<br />

28 His Master’s Voice<br />

A white dog with brown ears sits <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong> a gramophone, head directed to its brass-horn and slightly tilted to one side. <strong>The</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g was purchased <strong>in</strong> 1899, along<br />

with its full copyright, by the emerg<strong>in</strong>g Gramophone Company from the artist Francis Barraud.<br />

Text by Concepcion Cortes Zulueta<br />

31 <strong>The</strong> Tiger <strong>in</strong> the Tank<br />

Despite the complexities and <strong>in</strong>constancies <strong>of</strong> the human-animal relationship non-human animals [1] have been <strong>in</strong>timately <strong>in</strong>terwoven with<strong>in</strong> human culture for thousands <strong>of</strong><br />

years. Representations <strong>of</strong> animals exist across many mediums, with roots clearly visible <strong>in</strong> Palaeolithic cave pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs and early carv<strong>in</strong>gs, evolv<strong>in</strong>g human language, music and<br />

drama, and narrative fables and folk stories. Unsurpris<strong>in</strong>gly then animal representations cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be rife throughout our modern lives and across much popular media.<br />

Text by Cluny South<br />

39 Bovril by Electrocution<br />

I first came across this illustration whilst brows<strong>in</strong>g through Leonard de Vries’s fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g collection, Victorian Advertis<strong>in</strong>g, about twelve years ago. I was look<strong>in</strong>g for someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

else at the time – examples <strong>of</strong> late Victorian electric belt advertisements as part <strong>of</strong> a project on n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century medical electricity. Instead, this one jumped out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

page at me.<br />

Text by Iwan Rhys Morus<br />

42 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Animals</strong> Are “Break<strong>in</strong>g Out”!<br />

This paper explores recent TV adverts <strong>in</strong> which the animals portrayed come to appear before us <strong>in</strong> new ways. Gone are cosy images <strong>of</strong> chimpanzees play<strong>in</strong>g house, wear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

flat-caps and frocks, and pour<strong>in</strong>g cups <strong>of</strong> tea. <strong>The</strong> animals are break<strong>in</strong>g out! Mary, the cow (Muller yoghurt), is “set free” on a beach to fulfil her dream <strong>of</strong> becom<strong>in</strong>g a horse.<br />

More cows (Anchor butter) have taken charge <strong>of</strong> the dairy.<br />

Text by Louise Squire<br />

49 Can You Say, “Awww”?<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> have long been a regular theme <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g, especially when anthropomorphized. Except for obvious ties to products like dog food and pet products, animals<br />

usually have noth<strong>in</strong>g to do with the goods or services advertised, but we connect with them and the products nonetheless, and we get a good feel<strong>in</strong>g when a company is<br />

associated with cute animals.<br />

Text by Gene Gable<br />

51 Evolution and Design<br />

<strong>The</strong> animal as sign has a long evolutionary history, but with the onset <strong>of</strong> cultural modernity it began to assume new semiotic forms. Foucault describes a new field <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>creased visibility that emerged <strong>in</strong> the eighteenth century which gave rise to a complex semiotic system with<strong>in</strong> which the sign began to take on a life <strong>of</strong> its own. If images<br />

could be regarded as liv<strong>in</strong>g organisms, how could this affect their representational values <strong>in</strong> society? And, what are the implications for the lives and representation <strong>of</strong> animals?<br />

Text by Sonja Britz<br />

61 Nervous Dogs Need Adm<strong>in</strong>, Son!<br />

This advert comes from a British magaz<strong>in</strong>e <strong>The</strong> Tail Wagger, October 1940. <strong>The</strong> Tail- Waggers Club had been founded <strong>in</strong> 1928 to promote dog welfare stat<strong>in</strong>g, ‘<strong>The</strong> love<br />

<strong>of</strong> animals, and especially <strong>of</strong> dogs, is <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> nearly all Britishers’ and by 1930 numbered some 300,000 members. [i] All dogs were eligible for membership, not just those<br />

from established breeds. By July 1930 it had become a general legal requirement that all dogs should wear collars and the club and magaz<strong>in</strong>e endorsed such measures. [ii]<br />

Text by Hilda Kean<br />

64 A Stony Field<br />

Brand representations proliferate reflexive identities <strong>of</strong> their producers and consumers. <strong>The</strong>se self-advertisements re<strong>in</strong>scribe commodified identities reproductively back onto the<br />

subjects and objects – the represented figures – <strong>of</strong> consumption. In this paper I argue that the cooption <strong>of</strong> identity politics by mult<strong>in</strong>ational corporations like Stonyfield Farm,<br />

Inc. operates with<strong>in</strong> material and virtual doma<strong>in</strong>s that conceal fetishized processes <strong>of</strong> consumption.<br />

Text by Kather<strong>in</strong>e Bennett<br />

80 Brooke’s Monkey Brand Soap<br />

Brooke’s Monkey Brand Soap was a common, even iconic, presence <strong>in</strong> the pages <strong>of</strong> late n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century illustrated newspapers <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>. Barely an issue <strong>of</strong> the London<br />

Illustrated News, <strong>The</strong> Graphic or <strong>The</strong> Sketch passed without a full or half page spread <strong>of</strong> Brooke’s ubiquitous monkey, arrayed <strong>in</strong> one <strong>of</strong> its many baffl<strong>in</strong>g guises:<br />

promenad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> top hat and tails, juggl<strong>in</strong>g cook<strong>in</strong>g pots <strong>in</strong> a jester’s get-up, strumm<strong>in</strong>g a mandol<strong>in</strong> on the moon, destitute and begg<strong>in</strong>g by the side <strong>of</strong> the road, kneel<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

accept a medal from a glamorous Frenchwoman, career<strong>in</strong>g along on a bicycle with feet on the handle-bars, cl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g precariously to a ship’s mast, carefully polish<strong>in</strong>g the family<br />

ch<strong>in</strong>a and here <strong>in</strong> 1891, slid<strong>in</strong>g gleefully down the banisters with legs spread wide and the h<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> a smile while two neat Victorian children watch calmly on.<br />

Text by John Miller<br />

4

83 Jumbo: A Capitalist Creation Story<br />

Today, a pr<strong>of</strong>usion <strong>of</strong> non-human animals <strong>in</strong>habit the world <strong>of</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g. Consumers see some <strong>of</strong> them <strong>in</strong> person and some as brand icons, team mascots, and other moregeneric<br />

endorsers <strong>of</strong> consumption (sometimes their own consumption, like pig characters decorat<strong>in</strong>g BBQ restaurants or matronly cows on dairy product packag<strong>in</strong>g)<br />

embellish<strong>in</strong>g countless products, services and enterta<strong>in</strong>ments. This zoological cornucopia provides a naturaliz<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>k to the non-human world, promis<strong>in</strong>g us that to absorb<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g messages and spend is to participate <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>evitable and emotionally authentic activity because, as the belief goes, animals don’t lie (Shuk<strong>in</strong> 2009, 3-5).<br />

Text by Susan Nance<br />

95 None Tougher<br />

Rh<strong>in</strong>oceroses are rarely anthropomorphized mak<strong>in</strong>g this American magaz<strong>in</strong>e advertisement from the 1950s an unusual specimen. Armstrong, a rubber and tire company,<br />

found the tough exterior <strong>of</strong> rh<strong>in</strong>oceroses the prime comparison for its most durable automobile tires, dubbed “Rh<strong>in</strong>o-Flex.”<br />

Text by Kelly Enright<br />

98 From Animal Rights and Shock Advocacy to K<strong>in</strong>ship with <strong>Animals</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> visual cultures manifested <strong>in</strong> the advertis<strong>in</strong>g and communication activities <strong>of</strong> animal rights activists and those concerned with the conservation <strong>of</strong> species may<br />

be counter-productive, creat<strong>in</strong>g an ever-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g cultural distance between the human and the animal. By cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to position animals as subjugated,<br />

exploitable others, or as creatures that belong <strong>in</strong> a romanticized ‘nature’ separate from the human, communications campaigns may achieve effects that are<br />

contrary to those desired. <strong>The</strong> unashamed, cheaply voyeuristic nature <strong>of</strong> shock imagery may w<strong>in</strong> headl<strong>in</strong>es while worsen<strong>in</strong>g the overall position <strong>of</strong> the animal <strong>in</strong><br />

human culture. We <strong>of</strong>fer an alternative way <strong>of</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about visual communication concern<strong>in</strong>g animals – one that is focused on enhanc<strong>in</strong>g a sense <strong>of</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ship<br />

with animals. Based on empirical evidence, we suggest that cont<strong>in</strong>ued progress both <strong>in</strong> conservation and <strong>in</strong> animal rights does not depend on cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

castigation <strong>of</strong> the human but rather on embedd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our cultures the type <strong>of</strong> human-animal relationship on which positive change can be built.<br />

Text by Joe Zammit-Lucia and L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong><br />

112 Fad <strong>of</strong> the Year<br />

At the end <strong>of</strong> 2010 one <strong>of</strong> the UK’s commercial television channels, ITV, selected twenty <strong>of</strong> the most popular TV adverts from the year and entered them <strong>in</strong> to their own<br />

competition to f<strong>in</strong>d the television ‘Ad <strong>of</strong> the Year’. <strong>The</strong> w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g advert was one featur<strong>in</strong>g a rescue dog called Harvey who is <strong>in</strong> kennels, hop<strong>in</strong>g somebody will come along and<br />

adopt him.<br />

Text by Natalie Gilbert<br />

114 <strong>The</strong> Saddest Show on Earth<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce 1884, children across the United States have been dazzled by the sequ<strong>in</strong>ed wonders <strong>of</strong> the R<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g Bros. Circus. For many a youngster the spectacle <strong>of</strong> costumed<br />

elephants perform<strong>in</strong>g myriad tricks under the big top is a highlight <strong>of</strong> the show. Yet the bright spotlight <strong>of</strong> the center r<strong>in</strong>g casts a dark shadow across this American <strong>in</strong>stitution.<br />

Persistent allegations <strong>of</strong> elephant abuse have trailed the travell<strong>in</strong>g show for years.<br />

Text and <strong>in</strong>terview questions to Jeremy Smallwood and Pam Mufson by Chris Hunter<br />

120 Happy Easter<br />

Even if we are talk<strong>in</strong>g about this image as an “advertisement”, it is clear that its scope is not bus<strong>in</strong>ess, but to <strong>in</strong>form and raise consciousness about the slaughter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

animals. <strong>The</strong> message itself is rather peculiar: it’s obviously about animals, but without <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any image <strong>of</strong> them <strong>in</strong> the picture. If a contradiction exists, it has noth<strong>in</strong>g to do<br />

with the message conveyed by the advertisement, but rather with ambiguous attitudes <strong>of</strong> humans towards animals. In this case, it’s the lambs who are not portrayed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

advertisement.<br />

Text by Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti<br />

123 <strong>Animals</strong> on the Runway<br />

<strong>The</strong> discussion <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong> graphic art has radically changed s<strong>in</strong>ce about 1950. In contemporary performances and <strong>in</strong>stallations, even liv<strong>in</strong>g animals are displayed, which<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten leads to ethical discussions. Recent work, however, reflects a new societal view <strong>of</strong> animals: A strictly anthropocentric view has had its day, now animals have come to be<br />

seen as equal creatures and have emancipated themselves <strong>in</strong> artistic representation.<br />

Text by Bett<strong>in</strong>a Richter<br />

132 ‘Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration’ Posters<br />

In 1933 and 1934, as part <strong>of</strong> the “New Deal” economic plan for the United States, President Frankl<strong>in</strong> Roosevelt’s adm<strong>in</strong>istration created a new federal agency called the<br />

Works Progress Adm<strong>in</strong>istration (WPA) to hire artists to document and promote American cultural life.<br />

Text by Susan Nance<br />

136 Kill ‘em dead!: the Ord<strong>in</strong>ary Practices <strong>of</strong> Pest Control <strong>in</strong> the Home<br />

In recent years critical animal geographies have po<strong>in</strong>ted to dearth <strong>of</strong> stories about the small, the microscopic, the slimy and the abject. <strong>The</strong> exoskeleton, though pa<strong>in</strong>fully<br />

present to anyone bitten by a bedbug or disgusted by a cockroach, has been all but absent <strong>in</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant animal geographies. Death and the kill<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> animals is a further<br />

notable absence. However, this scholarly absence is not parallel with<strong>in</strong> the popular imag<strong>in</strong>ation, where cockroaches, files and dust mites loom large at the centre <strong>of</strong> a<br />

homemak<strong>in</strong>g war focused on the eradication <strong>of</strong> house pests.<br />

Text by Emma Power<br />

5

S<br />

<strong>in</strong>ce the Sixties, ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist philosophical<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g has been underl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the strong<br />

connection between sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation,<br />

exploitation <strong>of</strong> nonhuman animals, and abuse <strong>of</strong><br />

natural resources. <strong>The</strong>se three phenomena have<br />

been seen as so deeply <strong>in</strong>terconnected, both<br />

conceptually and historically, that they can be<br />

adequately understood and handled only as a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle question. What the ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ists state –<br />

and the image presented <strong>in</strong> this advert confirms<br />

– is that <strong>in</strong> Western patriarchal civilization,<br />

women, nonhuman animals, and the<br />

environment are categories related to ‘animated<br />

properties’, or ‘mobile goods’.<br />

How should these logically fallacious and<br />

discrim<strong>in</strong>atory messages be handled, criticized,<br />

and discouraged? <strong>The</strong> ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist philosopher<br />

Val Plumwood suggests to contrast the<br />

patriarchal conceptual framework through a<br />

careful work <strong>of</strong> revaluation, celebration, and<br />

defense <strong>of</strong> what male dom<strong>in</strong>ion subdues. On<br />

the one hand, dichotomical metaphors<br />

underrate the fem<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e as related to corporeality,<br />

emotions, <strong>in</strong>tuitiveness, cooperation, care, and<br />

sympathy; on the other hand, the mascul<strong>in</strong>e is<br />

celebrated as related to opposed concept,<br />

such as rationality, <strong>in</strong>tellect, competition,<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ion, and apathy (Plumwood, 1992).<br />

6<br />

EAT ME TENDER<br />

Love can be dangerous when it comes to cook<strong>in</strong>g. In this image, the evidence that a ‘lover’ wants to possess his<br />

woman just like a ‘meat lover’ wants to eat his steak is exposed <strong>in</strong> a grotesque way. Sexist discrim<strong>in</strong>ation and<br />

animal exploitation are here associated to ‘love’, understood as an abuse mitigated by tenderness and care <strong>in</strong> the<br />

act <strong>of</strong> possess<strong>in</strong>g and kill<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Text by Adele Tiengo and Matteo Andreozzi<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most powerful ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ist approach<br />

to the issue <strong>of</strong> animal exploitation as a practice<br />

focused on – but not restricted to – food is Carol<br />

Adams’ <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat. Published <strong>in</strong><br />

1990, Adams’ book comb<strong>in</strong>es the author’s<br />

experience as a fem<strong>in</strong>ist activist and her<br />

academic researches to formulate the l<strong>in</strong>k<br />

between the perception <strong>of</strong> nonhuman animals<br />

and women as ‘consumable bodies’, <strong>of</strong>fered to<br />

men’s pleasure. Adams suggests that both<br />

women and animals are victims <strong>of</strong> a process <strong>of</strong><br />

objectification, fragmentation, and<br />

consumption, especially <strong>in</strong> visual, textual, and<br />

discursive texts. Through metaphor, a subject is<br />

objectified, then fragmented and separated<br />

from its ontological mean<strong>in</strong>g, and consumed as<br />

an object, exist<strong>in</strong>g only through what it<br />

represents. In the Meat Lovers advertisement, the<br />

woman/cow is an object <strong>of</strong> consumption and<br />

the representation <strong>of</strong> the patriarchal idea <strong>of</strong> love<br />

as dom<strong>in</strong>ion and possession.<br />

Many are also the analogies between Adams’<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation and Derrida’s<br />

carnophallogocentrism. Derrida uses this<br />

neologism to <strong>in</strong>dicate the predom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong><br />

rationality, mascul<strong>in</strong>ity, and carnivorous habits. In<br />

his <strong>in</strong>terview ‘Eat<strong>in</strong>g Well’, he clarifies this po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

admitt<strong>in</strong>g that women and vegetarians are

actually ethical, juridical and political subjects,<br />

as well as men and meat eaters. However, this is<br />

a recent achievement, and still «authority […] is<br />

attributed to the man (homo and vir) rather than<br />

to the woman, and to the woman rather than to<br />

the animal». And <strong>in</strong> fact, Derrida asks, how many<br />

possibilities are there that a head <strong>of</strong> State<br />

publicly and exemplarily declares himself – or<br />

herself – to be a vegetarian? (Derrida, 'Eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Well', or the Calculation <strong>of</strong> the Subject: An<br />

Interview with Jacques Derrida 1991, 114).<br />

Both identify meat eat<strong>in</strong>g and maleness<br />

as crucial elements <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g who is a<br />

subject. In particular, Derrida states that there are<br />

three fundamental conditions to recognize a<br />

subject as such, at least <strong>in</strong> Western cultures:<br />

La Capann<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Amanti della Carne (Meat Lovers), advert La Capann<strong>in</strong>a<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g «a meat eater, a man, and an<br />

authoritative, speak<strong>in</strong>g self» (Calarco qtd <strong>in</strong><br />

Adams, <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat 1990, 6).<br />

Adams develops this idea <strong>in</strong> a far more detailed<br />

way. In particular she focuses on the implications<br />

<strong>of</strong> the perception <strong>of</strong> animal/female bodies as<br />

‘consummable’ through butchery and rape,<br />

underl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the evidences <strong>of</strong> this analogy <strong>in</strong><br />

images, commercials, menu covers, and articles<br />

7<br />

that use the female body to attract the male<br />

meat eaters. In the case <strong>of</strong> the advertisement<br />

here presented, rigorously male meat eaters are<br />

<strong>in</strong>vited to consume their love for a steak on a<br />

bed <strong>of</strong> lettuce.<br />

However, rather than aggressive and<br />

pornographic, this k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> love seems tender and<br />

devoted. <strong>The</strong> cow’s head is ridiculously put on<br />

the body <strong>of</strong> a sleep<strong>in</strong>g woman and a man<br />

embraces her. <strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> the advertisement is to<br />

arouse a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> tenderness for the animal killed<br />

without putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to question the meat eater’s<br />

virility. In fact, the tenderness here displayed is<br />

the one that follows the sexual <strong>in</strong>tercourse<br />

between husband and wife, maybe. Curiously<br />

enough, it is the beloved steak that plays here<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> the absent referent. Both the woman<br />

and the cow are visually present <strong>in</strong> the image,<br />

but the object <strong>of</strong> the advertisement – meat – is<br />

only textually summoned. In fact, the proposed<br />

idea is that meat eat<strong>in</strong>g is a behaviour <strong>of</strong> car<strong>in</strong>g<br />

because the woman/cow wants to be object <strong>of</strong><br />

that k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> ‘tenderness’, mean<strong>in</strong>g that she wants<br />

to be eaten/consumed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> scene is not one <strong>of</strong> seduction, but <strong>of</strong>

marital love. Carol Adams clearly expla<strong>in</strong>s how<br />

the sexual politics <strong>of</strong> meat beg<strong>in</strong>s with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

exploitation <strong>of</strong> the reproductive functions <strong>of</strong><br />

female animals. Liv<strong>in</strong>g alone milk and eggs –<br />

which are products <strong>of</strong> maternity –, the majority <strong>of</strong><br />

meat comes from adult females and their<br />

babies. Female nonhuman animals are<br />

exploited to satisfy human appetites both when<br />

they are alive and when they are dead, while<br />

male animals are used much less <strong>in</strong> the food<br />

References<br />

Adams, Carol J. <strong>The</strong> Sexual Politics <strong>of</strong> Meat. Twentieth<br />

Anniversary Edition (2010). New York : Cont<strong>in</strong>uum, 1990.<br />

Derrida, Jacques. "'Eat<strong>in</strong>g Well', or the Calculation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Subject: An Interview with Jacques Derrida" <strong>in</strong> Who Comes<br />

After the Subject, edited by Eduardo Cadava, Peter Connor<br />

and Jean-Luc Nancy, 96-119. New York and London:<br />

Routledge, 1991.<br />

Plumwood, Val. "Fem<strong>in</strong>ism and Ec<strong>of</strong>em<strong>in</strong>ism: Beyond the<br />

Dualistic Assumptions <strong>of</strong> Women, Men, and <strong>Nature</strong>." <strong>The</strong><br />

Ecologist 22, no. 1 (January/February 1992).<br />

8<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry, because they don’t produce anyth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g their lives and their meat is considered as<br />

less succulent and tasty. In an analogous way,<br />

female human animals are exploited ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

when they are alive for their sexual and<br />

reproductive function and, basically, to satisfy<br />

men’s pleasure. <strong>The</strong> Meat lovers image makes it<br />

clear that not much has changed, s<strong>in</strong>ce the<br />

Sixties: females <strong>of</strong> all species are ‘objects’ <strong>of</strong> love<br />

and properties <strong>of</strong> men.<br />

Adele Tiengo is a Ph.D. student <strong>in</strong> Foreign Languages, Literatures,<br />

and <strong>Culture</strong>s at the University <strong>of</strong> Milan (Italy), where she graduated<br />

<strong>in</strong> 2012 with a thesis on the relationship between literature and<br />

ethics <strong>in</strong> the animal question. In 2011 she spent a period as a<br />

visit<strong>in</strong>g researcher at the University <strong>of</strong> Alcalà (Spa<strong>in</strong>), thanks to the<br />

Susan Fenimore Cooper scholarship. She is currently carry<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

her research activities <strong>in</strong> ecocriticism.<br />

Matteo Andreozzi is a PhD student <strong>in</strong> Philosophy at University <strong>of</strong><br />

Milan, Italy. His research is ma<strong>in</strong>ly on Environmental Ethics and<br />

Movements, with a special focus on the analysis and the<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic value concept. He is author <strong>of</strong> the<br />

book Verso Una Prospettiva Ecocentrica. Ecologia Pr<strong>of</strong>onda e<br />

Pensiero a Aete[Head<strong>in</strong>g Toward an Ecocentric M<strong>in</strong>dset. Deep<br />

Ecology and Reticular Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g], 2011 and editor <strong>of</strong> the book<br />

Etiche dell’Ambiente. Voci e Prospettive [Environmental Ethics.<br />

Voices and Perspectives], 2012. He is also representative member<br />

<strong>of</strong> ENEE (European Network for Environmental Ethics) and MAnITA<br />

(M<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Animals</strong> Italy) and member <strong>of</strong> ISEE (International Society<br />

for Environmental Ethics) and ESFRE (European Forum for the Study<br />

<strong>of</strong> Religion and the Environment). For further <strong>in</strong>formation please<br />

visit http://www.matteoandreozzi.it or<br />

http://unimi.academia.edu/MatteoAndreozzi.

A<br />

merican popular culture has quietly<br />

become <strong>in</strong>habited by all sorts <strong>of</strong> talk<strong>in</strong>g<br />

animals and danc<strong>in</strong>g products that are<br />

used by advertisers to promote their brands.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se creatures, called trade characters, are<br />

fictional, animate be<strong>in</strong>gs, or animated objects,<br />

that have been created for the promotion <strong>of</strong> a<br />

product, service, or idea (Phillips 1996).<br />

Commercials with these characters score above<br />

average <strong>in</strong> their ability to change brand<br />

preference (Stewart and Furse 1986). It appears,<br />

then, that trade characters can be effective<br />

communication tools. However, it is unclear why<br />

this is so. Although trade characters are popular<br />

with advertisers and consumers, their role <strong>in</strong><br />

communicat<strong>in</strong>g the advertis<strong>in</strong>g message has<br />

been generally taken for granted without<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation. It has been<br />

hypothesized that there are several reasons why<br />

advertisers use trade characters: to attract<br />

attention, enhance identification <strong>of</strong> and memory<br />

ADVERTISING AND THE<br />

CULTURAL MEANING<br />

OF ANIMALS<br />

One explanation for the proliferation <strong>of</strong> animal trade characters <strong>in</strong> current advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice proposes that they<br />

are effective communication tools because they can be used to transfer desirable cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs to products<br />

with which they are associated. <strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what messages these animals communicate is to<br />

explore the common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that they embody. This paper presents a qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

common themes found <strong>in</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> four animal characters. In addition, it demonstrates a method<br />

by which cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs can be elicited. <strong>The</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> this method for advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice<br />

are discussed.<br />

Text by Barbara J. Phillips<br />

9<br />

for a product, and achieve promotional<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uity (Phillips 1996). However, one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most important reasons for the use <strong>of</strong> trade<br />

characters <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g may be that they can<br />

be used to transfer desired mean<strong>in</strong>gs to the<br />

products with which they are associated. By<br />

pair<strong>in</strong>g a trade character with a product,<br />

advertisers can l<strong>in</strong>k the personality and cultural<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the character to the product <strong>in</strong> the<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> consumers. This creates a desirable<br />

image, or mean<strong>in</strong>g, for the product. <strong>The</strong> first step<br />

<strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g this explanation <strong>of</strong> trade character<br />

communication is to show that these characters<br />

do embody common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that can<br />

be l<strong>in</strong>ked to products. Research has shown<br />

that animal characters are one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

commonly used trade character types <strong>in</strong> current<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g practice (Callcott and Lee 1994).<br />

<strong>Animals</strong> have long been viewed as standard<br />

symbols <strong>of</strong> human qualities (Neal 1985; Sax<br />

1988). For example, <strong>in</strong> American culture,

"everyone" knows that a bee<br />

symbolizes<strong>in</strong>dustriousness, a dove represents<br />

peace, and a fox embodies cunn<strong>in</strong>g (Rob<strong>in</strong><br />

1932). It is likely that advertisers use animal<br />

characters because consumers understand the<br />

animals' cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs and consequently<br />

can l<strong>in</strong>k these mean<strong>in</strong>gs to a product. <strong>The</strong>refore,<br />

the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> animals may lie at the<br />

core <strong>of</strong> the mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> animal trade<br />

characters. This paper describes a method for<br />

elicit<strong>in</strong>g character mean<strong>in</strong>gs, presents a<br />

qualitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong><br />

four animal characters, and discusses the<br />

broader implications that these results have for<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g research and practice. This<br />

qualitative study <strong>of</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs is<br />

motivated by several issues: Understand<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that consumers assign to<br />

animal characters will assist <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

successful advertis<strong>in</strong>g campaigns; practitioners<br />

can create characters that embody desired<br />

brand mean<strong>in</strong>gs while avoid<strong>in</strong>g characters with<br />

negative associations. In addition, by<br />

highlight<strong>in</strong>g an underutilized research method by<br />

which the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> characters can<br />

be elicited, this paper presents a way for<br />

practitioners, researchers, and regulators to<br />

understand what messages specific characters<br />

are communicat<strong>in</strong>g to their audiences. This<br />

method may be useful <strong>in</strong> other types <strong>of</strong><br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g research as well. Researchers have,<br />

<strong>in</strong> the past, asked for measures <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g for celebrity endorsers (McCracken<br />

1989) and for symbolic advertis<strong>in</strong>g images (Scott<br />

1994), as well. F<strong>in</strong>ally, by show<strong>in</strong>g that animal<br />

characters have common cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

this paper builds support for one <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

empirical explanations <strong>of</strong> how trade characters<br />

"work" <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g, and creates a foundation<br />

for future trade character research.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next section <strong>of</strong> the paper will present<br />

the theories used to illum<strong>in</strong>ate the research<br />

question: Do there exist shared mean<strong>in</strong>gs that<br />

consumers associate with specific animal<br />

characters? If so, how can these mean<strong>in</strong>gs be<br />

elicited, and what are their common themes?<br />

<strong>The</strong> third section will <strong>in</strong>troduce a method by<br />

which the cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> characters can<br />

be elicited, and will present the procedures used<br />

<strong>in</strong> this research study. <strong>The</strong> fourth section will<br />

discuss the results <strong>of</strong> the study, and the last<br />

section will draw general conclusions.<br />

Conceptual Development <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Research Question It has been suggested that<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g functions, <strong>in</strong> general, by attempt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to l<strong>in</strong>k a product with an image that elicits<br />

10<br />

desirable emotions and ideas (McCracken 1986).<br />

For example, the image <strong>of</strong> a child may <strong>in</strong>voke<br />

feel<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> pleasure, nostalgia, and playfulness. By<br />

show<strong>in</strong>g a product next to such an image,<br />

advertis<strong>in</strong>g encourages consumers to associate<br />

the product with the image. Through this<br />

association, the product acquires the image's<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Trade characters may be one type <strong>of</strong><br />

image that advertisers use because these<br />

characters possess learned cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se mean<strong>in</strong>gs are similar to the personalities<br />

that consumers associate with characters from<br />

other sources such as movies, cartoons, and<br />

comic books. For example, Mickey Mouse is<br />

viewed as a "nice guy," while Bugs Bunny is seen<br />

as clever, but mischievous. Individuals do not<br />

<strong>in</strong>vent their own mean<strong>in</strong>g for cultural symbols;<br />

they must learn what each symbol means <strong>in</strong> their<br />

culture (Berger 1984) based on their experiences<br />

with the character. For example, consumers'<br />

ideas about the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> "elephant" are<br />

shaped by Dumbo movies and African safari TV<br />

programs, and are colored by news stories about<br />

a rampag<strong>in</strong>g elephant that trampled its tra<strong>in</strong>er.<br />

Consequently, although each <strong>in</strong>dividual br<strong>in</strong>gs his<br />

or her own experience to the mean<strong>in</strong>g ascription<br />

process, consensus <strong>of</strong> character mean<strong>in</strong>g across<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals is possible through common cultural<br />

experience.<br />

In advertis<strong>in</strong>g, trade characters' mean<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

are used to visually represent the product<br />

attributes (Zacher 1967) or the advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

message (Kleppner 1966). For example, Mr.<br />

Peanut embodies sophistication (Kapnick 1992),<br />

the Pillsbury Doughboy symbolizes fun (PR<br />

Newswire 1990), and the lonely Maytag repairman<br />

stands for reliability (Elliott 1992). However, the<br />

consumer must correctly decode the trade<br />

character's mean<strong>in</strong>g before it can have an<br />

impact (McCracken 1986). <strong>The</strong>refore, characters'<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs must be easily understood by<br />

consumers if they are to correctly <strong>in</strong>terpret the<br />

character's message. As a result, advertisers<br />

frequently use animal trade characters (Callcott<br />

and Lee 1994) because consumers are thought<br />

to have learned the animals' cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

and consequently are likely to correctly decode<br />

the advertis<strong>in</strong>g message.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the association<br />

between animal trade characters and the<br />

products they promote is to explore the symbolic<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs conveyed by the animals used <strong>in</strong> these<br />

advertisements. That is, if an advertiser places a<br />

bear (e.g., Snuggle) or a dog (e.g., Spuds<br />

McKenzie) next to his product, what do these

animals represent to the audience? Rather than<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dividual animal characters, however,<br />

it is necessary to first study an animal's general<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g. This is because the animal<br />

category (e.g., bear, dog, etc.) provides the<br />

primary, or core, mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

character. Although an advertiser can choose to<br />

highlight certa<strong>in</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs over others<br />

(e.g., "s<strong>of</strong>tness" for Snuggle Bear and "wildness"<br />

for Smokey Bear), the core set <strong>of</strong> animal<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs dictate what is possible for that<br />

character to express. Snuggle fabric s<strong>of</strong>tener<br />

would not f<strong>in</strong>d it easy to use a porcup<strong>in</strong>e, pig, or<br />

flam<strong>in</strong>go to express "s<strong>of</strong>tness."<br />

In addition, by study<strong>in</strong>g the broad animal<br />

category to which the character belongs, it is<br />

possible to make generalizations that can help<br />

practitioners create and use animal characters<br />

effectively. For example, if advertisers know that<br />

the animal "cat" shares several positive core<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs, they can create cat characters that<br />

capitalize on those mean<strong>in</strong>gs. Alternatively, if<br />

"cat" mean<strong>in</strong>gs conta<strong>in</strong> negative attributes that<br />

reflect badly on the associated product,<br />

advertisers may want to use a different<br />

character.<br />

Method<br />

It is difficult to explore the perceived mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

a trade character by ask<strong>in</strong>g subjects directly, as<br />

their responses tend to be superficial and<br />

descriptive. "Smokey Bear? Oh, he's brown and<br />

wears a hat." Other qualitative methods, such as<br />

<strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g, tend to be time- and labor<strong>in</strong>tensive<br />

C features that advertisers may want to<br />

avoid. As an alternative, word association is an<br />

easy and efficient method for explor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

psychological mean<strong>in</strong>g. It can be adm<strong>in</strong>istered<br />

to a group and can elicit the mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> more<br />

than one animal per session, yet provides rich<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation regard<strong>in</strong>g cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g. Szalay<br />

and Deese (1978) state that because a word<br />

association task does not require subjects to<br />

communicate their <strong>in</strong>tentions, it decreases<br />

subjects' rationalizations, and it taps associations<br />

that are difficult to express or expla<strong>in</strong>. Further,<br />

word association does not require thoughts to be<br />

expressed <strong>in</strong> a structural manner. Instead, this<br />

technique produces expressions <strong>of</strong> thought that<br />

are immediate and spontaneous, and this<br />

spontaneity, along with an imposed time<br />

constra<strong>in</strong>t, is thought to reduce subjects' selfmonitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and conscious edit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> responses.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, the method reduces experimenter bias<br />

because no organization or categories are<br />

11<br />

imposed on subjects to limit their responses C a<br />

primary draw-back <strong>of</strong> quantitative research. <strong>The</strong><br />

word association method is not new; other<br />

market<strong>in</strong>g and advertis<strong>in</strong>g researchers have used<br />

it to understand how consumers perceive<br />

products (Kle<strong>in</strong>e and Kernan 1991) and to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e a product's attributes to aid <strong>in</strong> product<br />

position<strong>in</strong>g (Friedmann 1986). However, perhaps<br />

because it is "old hat," this method has been<br />

consistently overlooked and underutilized <strong>in</strong><br />

consumer behavior research.<br />

In the present study, <strong>in</strong>formants were asked<br />

to respond to verbal animal names dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

word association task (e.g., "bear") rather than to<br />

visual images <strong>of</strong> the animal. Verbal animal names<br />

are thought to elicit broad responses that reflect<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>formation that an <strong>in</strong>dividual has<br />

learned to associate with the category, "bear." In<br />

contrast, the way an animal is visually portrayed<br />

can narrow its mean<strong>in</strong>g (Berger 1984). A realistic<br />

picture <strong>of</strong> a bear may elicit a different part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

core mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> "bear" than a cartoon bear.<br />

Images <strong>of</strong> actual trade characters, such as<br />

Smokey Bear or Snuggle, may elicit even narrower<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs associated only with those characters.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, verbal animal names were used to<br />

generate broad, complete responses. However, it<br />

is possible that advertisers could use both verbal<br />

and visual animals <strong>in</strong> a word association task<br />

when creat<strong>in</strong>g characters. Responses to the<br />

verbal animal name would provide core<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs, while responses to the visual character<br />

would provide a measure <strong>of</strong> how successfully the<br />

particular representation <strong>of</strong> an animal captured<br />

desired mean<strong>in</strong>gs. This possibility will be discussed<br />

further <strong>in</strong> the conclusion section <strong>of</strong> this paper.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants for this study were 21 male<br />

and 15 female undergraduate students enrolled<br />

<strong>in</strong> an advertis<strong>in</strong>g management course at a major<br />

state university. Students participated <strong>in</strong> the study<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g their regular class time. Of these<br />

respondents, 92% were between the ages <strong>of</strong> 20<br />

and 25. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this student sample precludes<br />

conclud<strong>in</strong>g that the results <strong>of</strong> this study reflect the<br />

"true" cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> each animal. However,<br />

this sample is useful to show that a common<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>g for each animal exists <strong>in</strong> a<br />

homogeneous population and can be elicited<br />

through research, whether that population is<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> undergraduate students or other<br />

target markets <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest to advertisers. Each<br />

<strong>in</strong>formant received a package conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a<br />

cover page, an <strong>in</strong>struction page, and five word<br />

association sheets.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>structions for the word association<br />

task were read aloud and <strong>in</strong>formants' questions

egard<strong>in</strong>g the task were answered. For each word<br />

association task, respondents had one m<strong>in</strong>ute to<br />

write one-word descriptions <strong>of</strong> whatever came to<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d when they thought about the animal listed<br />

at the top <strong>of</strong> the page (Szalay and Deese 1978).<br />

Informants were <strong>in</strong>structed to write these words <strong>in</strong><br />

the order <strong>in</strong> which they came to m<strong>in</strong>d and it was<br />

stressed that there were no wrong answers. <strong>The</strong><br />

first animal listed <strong>in</strong> the package was lobster,<br />

which was used as a practice task to familiarize<br />

students with the word association method. After<br />

complet<strong>in</strong>g the practice task, <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g questions about the task were<br />

answered. Respondents then completed four<br />

more animal word associations, respond<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

words: pengu<strong>in</strong>, ant, gorilla, and raccoon. <strong>The</strong><br />

particular animals were chosen to reflect the<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the author; other animals could<br />

illustrate the commonality <strong>of</strong> animal mean<strong>in</strong>gs as<br />

well. <strong>The</strong> order <strong>in</strong> which the four animals were<br />

presented was randomized to control for order<br />

effects.<br />

<strong>The</strong> words generated by <strong>in</strong>formants <strong>in</strong><br />

response to the animal word association were<br />

grouped <strong>in</strong>to categories, or themes that emerged<br />

from the data. Each animal was analyzed<br />

separately, except lobster, the practice task,<br />

which was not coded. For each animal, words<br />

that were similar <strong>in</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g or that had a<br />

common theme were grouped together. Each<br />

<strong>in</strong>formant's responses were added to the tentative<br />

themes discovered <strong>in</strong> the previous <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

responses, thus support<strong>in</strong>g those themes or<br />

allow<strong>in</strong>g them to be changed (Strauss and Corb<strong>in</strong><br />

1990). Guidel<strong>in</strong>es suggested by Szalay and Deese<br />

(1978) were followed when identify<strong>in</strong>g common<br />

themes.<br />

Words that could not be placed <strong>in</strong>to any<br />

category were placed <strong>in</strong>to an "other" category.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se words did not have an identifiable<br />

association with the animal; they are thought to<br />

be associations to words other than the animal<br />

(i.e., cha<strong>in</strong> associations) or words that show that<br />

the respondent was th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> someth<strong>in</strong>g other<br />

than the task at hand. <strong>The</strong>re were only 10 to 16 <strong>of</strong><br />

these words for each animal.<br />

A second researcher re-classified all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

response words <strong>in</strong>to the categories to check the<br />

soundness <strong>of</strong> the themes. <strong>The</strong>re was an <strong>in</strong>itial 86%<br />

agreement between researchers; disagreements<br />

were resolved through discussion and re-analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formant responses. <strong>The</strong> response words for all<br />

<strong>of</strong> the animals are available from the author.<br />

12<br />

COGNITIVE MAP OF PENGUIN THEMES<br />

<strong>The</strong> themes elicited <strong>in</strong> response to each animal<br />

were illustrated us<strong>in</strong>g cognitive maps, represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a pictorial overview <strong>of</strong> each animal's mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cognitive map summarizes the objects and<br />

ideas that <strong>in</strong>formants collectively associate with<br />

each animal, and organizes these associations<br />

<strong>in</strong>to mean<strong>in</strong>gful themes (Coleman 1992). <strong>The</strong><br />

cognitive map also identifies the number <strong>of</strong> times<br />

each theme was mentioned, giv<strong>in</strong>g an idea <strong>of</strong><br />

the relative importance <strong>of</strong> each theme to the<br />

animal's shared mean<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION<br />

General Results<br />

Informants mentioned between 315 and 386<br />

words <strong>in</strong> response to each animal, or<br />

approximately 9 to 11 words per <strong>in</strong>dividual. It was<br />

surpris<strong>in</strong>g that more than 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

responses could be classified <strong>in</strong>to six or seven<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> themes for each animal. In addition,<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants' words were easily coded <strong>in</strong>to these<br />

themes, reflect<strong>in</strong>g a high degree <strong>of</strong> similarity<br />

between respondents. Also, words with the highest<br />

frequencies were mentioned by 8 to 25<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals, which suggests a high degree <strong>of</strong><br />

consistency across <strong>in</strong>dividuals' responses. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

results support the idea that there exist shared<br />

cultural mean<strong>in</strong>gs that consumers generally<br />

associate with animals, and that these mean<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

can be elicited through word association.<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, although it was not the <strong>in</strong>tent<br />

at the outset, the themes that emerged from the<br />

data were remarkably similar between animals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> primary themes mentioned by <strong>in</strong>formants<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude: (a) Appearance, (b) Habitat, (c)<br />

Personality, (d) Human/animal <strong>in</strong>teraction, (e)<br />

Popular culture, and (f) Behavior. <strong>The</strong>se six<br />

categories seem to be most salient for<br />

consumers, and may <strong>of</strong>fer the greatest help <strong>in</strong><br />

creat<strong>in</strong>g animal characters for use <strong>in</strong> advertis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

campaigns. Appearance summarizes <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

mental images <strong>of</strong> the animal C how they expect<br />

the animal to look; Habitat describes <strong>in</strong>formants'<br />

expectations <strong>of</strong> where these animals live and the<br />

objects that surround them; Personality represents<br />

the personality traits that <strong>in</strong>formants associate with<br />

each animal; Human/animal <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

describes how humans coexist and <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

these animals; while Behavior describes their<br />

typical actions. Popular culture highlights cultural<br />

references that already exist for each animal,

Fig. 1.<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g sources such as television programs,<br />

movies, books, and ads. <strong>The</strong> themes for each<br />

animal are given below <strong>in</strong> greater detail.<br />

Pengu<strong>in</strong><br />

A cognitive map <strong>of</strong> the themes associated with<br />

"pengu<strong>in</strong>," along with the frequency with which<br />

they were mentioned, are shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 1. <strong>The</strong><br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes that emerge from the data are<br />

Habitat and Appearance.<br />

13<br />

Habitat <strong>in</strong>cludes a natural habitat made up <strong>of</strong> the<br />

subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) ice and snow, (b) cold, (c)<br />

places such as Antarctica and the South Pole,<br />

and (d) water. Informants also listed other<br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants <strong>of</strong> this environment such as fish, polar<br />

bears, and whales. Informants also mentioned<br />

Appearance as an important pengu<strong>in</strong> theme,<br />

focus<strong>in</strong>g on the subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) color, which<br />

was mostly black and white, (b) body parts such<br />

as w<strong>in</strong>gs, beaks, and feet, and (c) the formal<br />

tuxedo that pengu<strong>in</strong>s seem to be wear<strong>in</strong>g.

Fig. 2.<br />

Tuxedo was the most <strong>of</strong>ten mentioned word, with<br />

23 mentions. This strong association seems to<br />

have affected other themes, as discussed below.<br />

Both <strong>of</strong> the dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes suggest that a<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is associated with rich visual imagery.<br />

When confronted with the word "pengu<strong>in</strong>," it<br />

appears that <strong>in</strong>dividuals conjure up an image <strong>of</strong><br />

a pengu<strong>in</strong>, and describe him (Appearance) and<br />

his surround<strong>in</strong>gs (Habitat). This <strong>in</strong>terpretation is<br />

supported by a third theme, Behavior, which was<br />

mentioned less <strong>of</strong>ten. This category <strong>in</strong>cludes the<br />

subthemes <strong>of</strong>: (a) waddle, (b) swim, and (c) other<br />

actions, which also contribute to visual imagery.<br />

14<br />

Behavior was mentioned 44 times, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

respondents frequently visualize the pengu<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

motion.<br />

COGNITIVE MAP OF ANT THEMES<br />

In analyz<strong>in</strong>g the dom<strong>in</strong>ant themes, it seems that<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong>s are viewed as hav<strong>in</strong>g little <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

with humans. <strong>The</strong> pengu<strong>in</strong> appears to be isolated<br />

from all but a few Eskimos (accord<strong>in</strong>g to two<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants) except when viewed <strong>in</strong> a man-made<br />

habitat (e.g., "Sea World"), and even that type <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction is rarely mentioned (2% <strong>of</strong> the time).

This lack <strong>of</strong> human/pengu<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraction is not<br />

surpris<strong>in</strong>g given pengu<strong>in</strong>s' remote location <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world, and the fact that they are removed from<br />

<strong>in</strong>formants' daily experiences. Another theme,<br />

Personality, is characterized by a duality; for the<br />

most part, pengu<strong>in</strong>s are personified as silly<br />

creatures (e.g., cute, funny, go<strong>of</strong>y, playful, etc.),<br />

but they also can be viewed as formal animals<br />

(e.g., dist<strong>in</strong>guished, classy, behaved, mannered,<br />

etc.), even by the same <strong>in</strong>dividuals. This<br />

contradiction may stem from the fact that<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong>s are strange-look<strong>in</strong>g members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bird family and waddle comically <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong><br />

fly<strong>in</strong>g, but also appear to wear<strong>in</strong>g a tuxedo, a<br />

cultural symbol <strong>of</strong> formality and manners.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g pengu<strong>in</strong> themes are<br />

Popular culture and Categories. Pengu<strong>in</strong>s are<br />

associated with a surpris<strong>in</strong>gly large number <strong>of</strong><br />

popular culture references <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g movies,<br />

videogames, mascots, and cartoons. Categories<br />

refers to the hierarchical categorization <strong>of</strong><br />

objects, <strong>in</strong> which an object can be placed <strong>in</strong> a<br />

superset (generalization hierarchy) or a subset<br />

(part hierarchy) (Anderson 1990). For example, a<br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is a bird (superset), and a type <strong>of</strong><br />

pengu<strong>in</strong> is an emperor (subset). In the same way,<br />

a group <strong>of</strong> pengu<strong>in</strong>s is called a flock, or a herd<br />

(at least for one respondent).<br />

Ant<br />

A cognitive map <strong>of</strong> the "ant" themes is shown <strong>in</strong><br />

Figure 2. <strong>The</strong> three dom<strong>in</strong>ant ant themes are:<br />

Categories, Habitat, and Human/ant <strong>in</strong>teraction.<br />

Categories <strong>in</strong>cludes: (a) type <strong>of</strong> ant, such as red<br />

or army; (b) name <strong>of</strong> ant, such as worker or<br />

queen; (c) group <strong>of</strong> ants, such as colony; and (d)<br />

classification <strong>of</strong> ant, such as <strong>in</strong>sect. <strong>The</strong><br />

importance <strong>of</strong> this theme for ant contrasts sharply<br />

with that for pengu<strong>in</strong>; Categories was mentioned<br />

104 times for ant, but only 16 times for pengu<strong>in</strong>.<br />

This suggests that the ant themes are less<br />

associated with images, and more associated<br />

with verbal or propositional knowledge (Anderson<br />

1990). That is, when asked to respond to the word<br />

"ant," it appears that respondents retrieve verbal<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation that they have learned <strong>in</strong> the past,<br />

such as: the head ant is called the queen; the<br />

male ant is called the drone; ants live <strong>in</strong> colonies;<br />

etc. This <strong>in</strong>terpretation is supported by another<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant theme: Habitat, where the subthemes<br />

<strong>of</strong> (a) hill and (b) man-made habitat also appear<br />

to conta<strong>in</strong> verbal associations. For example, the<br />

most-<strong>of</strong>ten mentioned words <strong>in</strong> each subtheme,<br />

"hill" and "farm," could be elicited with a fill-<strong>in</strong>-the-<br />

15<br />

blank word task (i.e., "ant____"). <strong>The</strong> same cannot<br />

be said for pengu<strong>in</strong> (e.g., "pengu<strong>in</strong> ice," "pengu<strong>in</strong><br />

cold," etc.). Some imagery is associated with ant,<br />

though, as seen <strong>in</strong> the Habitat subtheme <strong>of</strong> (c)<br />

picnic. For the most part, however, other themes<br />

support verbal, non-imagery based associations<br />

for ant. For example, the ant's image-based<br />

themes, Appearance and Behavior, conta<strong>in</strong> far<br />

fewer words (31 and 7) than do these same<br />

categories for pengu<strong>in</strong> (103 and 44). Also, many<br />

<strong>of</strong> the words <strong>in</strong> Appearance, such as antenna,<br />

thorax, and abdomen, seem associated with<br />

knowledge propositions, rather than image.<br />

Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, even the Popular culture theme<br />

supports a verbal view because many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

responses <strong>in</strong> this category make use <strong>of</strong> word play<br />

such as "Aunt Bea" and "antichrist."<br />

A dom<strong>in</strong>ant theme for ant that did not exist<br />

for pengu<strong>in</strong> is Human/ant <strong>in</strong>teraction. This focus on<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction is understandable given that ants are<br />

usually part <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formants' daily environment and<br />

experience. In this category, ants <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

humans by annoy<strong>in</strong>g them and caus<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

pa<strong>in</strong>; "bite" was mentioned 19 times by<br />

respondents. Humans <strong>in</strong>teract with ants as<br />

exterm<strong>in</strong>ators; we kill them. It is surpris<strong>in</strong>g then, that<br />

under the theme Personality, ants are personified<br />

as hav<strong>in</strong>g more positive than negative qualities.<br />

Words like "strong," "hard-work<strong>in</strong>g," and<br />

"determ<strong>in</strong>ed" are used by respondents. Perhaps<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals have learned to associate these<br />