Meet Animal Meat - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Meet Animal Meat - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Meet Animal Meat - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

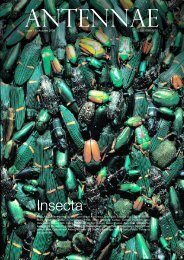

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

Issue 15 – W<strong>in</strong>ter 2010<br />

ISSN 1756-9575<br />

<strong>Meet</strong> <strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Meat</strong><br />

Bastien Desfriches Doria Mammal Thoughts Courtney Lee Weida Flash-Pots and Clay Bodies Cara Judea Alhadeff<br />

<strong>Meat</strong>: Digest<strong>in</strong>g the Stranger With<strong>in</strong> Simone Racheli <strong>The</strong> Biomechanics <strong>of</strong> Objects Gunter von Hagen<br />

<strong>The</strong> Problematic Exposure <strong>of</strong> Flesh Ron Broglio <strong>Meat</strong> Matters

<strong>Antennae</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Culture</strong><br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Academic Board<br />

Steve Baker<br />

Ron Broglio<br />

Matthew Brower<br />

Eric Brown<br />

Donna Haraway<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da Kal<strong>of</strong><br />

Rosemarie McGoldrick<br />

Rachel Poliqu<strong>in</strong><br />

Annie Potts<br />

Ken R<strong>in</strong>aldo<br />

Jessica Ullrich<br />

Carol Gigliotti<br />

Susan McHugh<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Bergit Arends<br />

Rod Bennison<br />

Claude d’Anthenaise<br />

Lisa Brown<br />

Rikke Hansen<br />

Petra Lange-Berndt<br />

Chris Hunter<br />

Karen Knorr<br />

Susan Nance<br />

Andrea Roe<br />

David Rothenberg<br />

Nigel Rothfels<br />

Angela S<strong>in</strong>ger<br />

Mark Wilson & Bryndís Snaebjornsdottir<br />

Helen Bullard<br />

Global Contributors<br />

Sonja Britz<br />

Tim Chamberla<strong>in</strong><br />

Lucy Davies<br />

Amy Fletcher<br />

Carol<strong>in</strong>a Parra<br />

Zoe Peled<br />

Julien Salaud<br />

Paul Thomas<br />

Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tonutti<br />

Johanna Willenfelt<br />

D<strong>in</strong>a Popova<br />

Amir Fahim<br />

Christ<strong>in</strong>e Marran<br />

Conception Cortes<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Lisa Brown<br />

Junior Copy Editor<br />

Maia Wentrup<br />

Front Cover: Poltrona 2006, wood, papier mache, wax. cm76x58x91h. Courtesy Paolo Maria Deanesi Gallery � Simone Racheli<br />

Back Cover: Lady Gaga’s <strong>Meat</strong> Dress as worn at the MTV Video Music Award 2010 on the 12 th <strong>of</strong> September 2010<br />

2

EDITORIAL<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 15<br />

I<br />

In 2002, Zhang Huan’s contribution to the Whitney Biennial, titled My New York, <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

xxxwear<strong>in</strong>g a suit made <strong>of</strong> fresh-cuts <strong>of</strong> meat stitched together which the artist wore down Fifth<br />

xxxAvenue, whilst releas<strong>in</strong>g doves from a cage, a Buddhist gesture <strong>of</strong> compassion. <strong>The</strong> work was<br />

xxxa response to September the 11th and sprung from the artist’s experience <strong>of</strong> the city as a<br />

visitor. “Many th<strong>in</strong>gs looked strong” recalls Huan, “but were extremely fragile. In New York, I saw<br />

men exercise beyond what their hearts could handle and take all k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> vitam<strong>in</strong>s and<br />

supplements to pump up their bodies. In this performance, I <strong>in</strong>vited immigrants to participate<br />

and used doves. My assistants designed an outfit <strong>of</strong> beef for me. It took five tailors one day and<br />

one night to stitch all the beef onto a div<strong>in</strong>g suit. <strong>The</strong> beef outfit was very heavy, maybe about<br />

fifty kilograms, and hard to walk <strong>in</strong>. What would take a bodybuilder more than ten years to<br />

achieve only took me one night!”<br />

As a performative act, My New York is charged with the presence <strong>of</strong> rich signifiers, the<br />

flesh, the doves, and not lastly, the presence <strong>of</strong> an artist from Beij<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> New York. Some have<br />

h<strong>in</strong>ted, the work could be read as a metaphor <strong>of</strong> America’s role <strong>in</strong> the contemporary sociopolitical<br />

world-scene. Others have distanced themselves from such read<strong>in</strong>gs. <strong>The</strong> flesh we see<br />

Zhang Huan wear<strong>in</strong>g is that <strong>of</strong> animals, not his own, however as the artist claims, it was<br />

symboliz<strong>in</strong>g his own flesh, simultaneously captur<strong>in</strong>g a sense <strong>of</strong> powerful strength, <strong>in</strong> the bulky and<br />

full forms <strong>of</strong> an alluded body-build<strong>in</strong>g anatomy and <strong>in</strong> the immense frailty rendered by the<br />

nakedness <strong>of</strong> the flesh which appears here at its most vulnerable as sk<strong>in</strong>ned. This ambiguity, a<br />

multi-signify<strong>in</strong>g agency <strong>of</strong> meat is explored <strong>in</strong> this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong>; our second <strong>in</strong>stallment on<br />

the subject. Ron Broglio captures this most effectively <strong>in</strong> the open<strong>in</strong>g paragraph <strong>of</strong> his essay,<br />

‘<strong>Meat</strong> Matters’ an extract from his forthcom<strong>in</strong>g book titled On the Surface: Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Animal</strong>s<br />

and Art.<br />

“In meat” says Broglio, “there is a transformation from liv<strong>in</strong>g to dead, from hidden to<br />

revealed, and from <strong>in</strong>digestible to edible. As the marker <strong>of</strong> this change, meat has a visceral<br />

materiality. <strong>The</strong> material form <strong>of</strong> dead animal flesh is haunted by the trace <strong>of</strong> a life transformed<br />

<strong>in</strong>to an object through the violence <strong>of</strong> death. <strong>The</strong> willful life <strong>of</strong> an animal becomes an object that<br />

shows little ability to resist human understand<strong>in</strong>g, manipulation, and consumption”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> artists’ work featured <strong>in</strong> this issue, directly explore all this. <strong>The</strong> photographic images <strong>of</strong><br />

Bastien Desfriches Doria and Cara Judea Alhadeff question meat and the subject <strong>of</strong> identity<br />

through the genre <strong>of</strong> portraiture and self-portraiture. Courtney Lee Weida explores the themes <strong>of</strong><br />

flesh and consumption through the surpris<strong>in</strong>g versatility <strong>of</strong> ceramics, whilst the work <strong>of</strong> Italian artist<br />

Simone Racheli br<strong>in</strong>gs us to reflect on the agency <strong>of</strong> meat as implicated <strong>in</strong> the relationship <strong>of</strong><br />

everyday objects. This issue also features an exclusive <strong>in</strong>terview with highly controversial artist<br />

Gunter von Hagen, the <strong>in</strong>ventor <strong>of</strong> the Body Worlds exhibitions which mercilessly expose flesh <strong>in</strong><br />

ways and contexts that many f<strong>in</strong>d problematic, but that other fully appreciate as science or art.<br />

Giovanni Aloi<br />

Editor <strong>in</strong> Chief <strong>of</strong> <strong>Antennae</strong> Project<br />

Zhang Huan was <strong>in</strong>terviewed by <strong>Antennae</strong> <strong>in</strong> May 2010<br />

3

Zhang Huan<br />

My New York, performance, 2002 © Zhang Huan<br />

4

CONTENTS<br />

ANTENNAE ISSUE 15<br />

6 Mammal Thoughts<br />

<strong>The</strong> series Mammal Thoughts explores the question<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> bodily identity <strong>in</strong>terweaved with philosophical self-reflection (the Cartesian Cogito). Each large format color portrait<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved an <strong>in</strong>tercollaborative dialogue between the photographer and the subject, encourag<strong>in</strong>g the latter to reappropriate his/her own particular understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> bodily<br />

representation through absurdity, absence, humor or eroticism while be<strong>in</strong>g presented as just a body.<br />

Text by Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

17 Flesh-Pots and Clay Bodies<br />

In this article, Courtney Lee Weida explores art practices <strong>of</strong> ceramics relat<strong>in</strong>g to themes <strong>of</strong> flesh and consumption. Beyond ceramic sculptures <strong>of</strong> animals and vessels used to<br />

store and serve meat, there are subtle themes and symbols <strong>of</strong> animals and flesh surround<strong>in</strong>g the clay medium.<br />

Text by Courtney Lee Weida<br />

27 <strong>Meat</strong>: Digest<strong>in</strong>g the Stranger With<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Meat</strong> becomes the reference through which I weave these fragmented body parts together <strong>in</strong>to literal and allusive connective tissue. I celebrate the return <strong>of</strong> my menstrual<br />

cycle by photograph<strong>in</strong>g my bloody menstrual pads juxtaposed to other allusions to sk<strong>in</strong>ned detritus—metal, rubber, mirror.<br />

Text by Cara Judea Alhadeff<br />

41 <strong>The</strong> Biomechanics <strong>of</strong> Objects<br />

Simone Racheli’s work is challeng<strong>in</strong>g and visionary. Through the simulation <strong>of</strong> biomechanical objects the artist questions our relationship with the world around us, and the<br />

psychological and philosophical ties we become entangled with. Here he discusses his work <strong>in</strong> an exclusive <strong>in</strong>terview with Zoe Peled.<br />

Questions by Zoe Peled<br />

Translation by Giovanni Aloi<br />

48 <strong>The</strong> Problematic Exposure <strong>of</strong> Flesh<br />

For over a decade, plast<strong>in</strong>ator Gunter von Hagen has enraged and fasc<strong>in</strong>ated audiences around the world through his always controversial Body Worlds shows. His work is<br />

carried out <strong>in</strong> the name <strong>of</strong> education but at times ethical considerations around his work tend to focus on the <strong>in</strong>appropriateness <strong>of</strong> some displays. We <strong>in</strong>terviewed the<br />

scientist/artist as his show focus<strong>in</strong>g on plast<strong>in</strong>ated animals hits the road.<br />

Questions by Giovanni Aloi<br />

Text by <strong>The</strong> Institution for Plast<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

58 <strong>Meat</strong> Matters<br />

<strong>Meat</strong> is the moment when what rema<strong>in</strong>ed hidden to us is opened up. <strong>The</strong> animal's <strong>in</strong>sides become outsides. Its depth <strong>of</strong> form becomes a surface, and its depth <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

becomes the th<strong>in</strong> lifelessness <strong>of</strong> an object exposed. <strong>Meat</strong> makes the animal <strong>in</strong>sides visible, and through sight, the animal body becomes knowable. And while meat serves as<br />

a means for us to take <strong>in</strong> the animal visually and <strong>in</strong>tellectually, it also marks the moment when the animal becomes physically consumable.<br />

Text by Ron Broglio<br />

5

I<br />

t is <strong>of</strong> significance that the grow<strong>in</strong>g relevancy<br />

<strong>of</strong> postmodern topography substantiates most<br />

<strong>of</strong> our contemporary critical th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> societal<br />

space and <strong>of</strong> its objective reflections on the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual s<strong>in</strong>ce the late sixties. As a provisional<br />

answer to globalization’s ever-<strong>in</strong>tensify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>of</strong> later capitalism <strong>in</strong>to the social —<br />

one should say existential — sphere, it seems that<br />

a descriptive theorization <strong>of</strong> our transfigured<br />

material milieu prevailed <strong>in</strong> contemporary<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. So that from the visual arts’ perspective,<br />

the emblematic figure <strong>of</strong> Rem Koolhaas’ generic<br />

city, or the peripheral landscapes <strong>of</strong> suburbanity<br />

<strong>in</strong> general, provide a certa<strong>in</strong> visibility regard<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s “Empire”.<br />

However, the question <strong>of</strong> how — what I would<br />

term —architectures <strong>of</strong> desublimation <strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong>uate<br />

the <strong>in</strong>dividual’s own materiality is becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly pert<strong>in</strong>ent with<strong>in</strong> the emerg<strong>in</strong>g context<br />

<strong>of</strong> postmodernity. <strong>The</strong> now dom<strong>in</strong>ant synthetic<br />

environment <strong>of</strong> human activities engendered by<br />

computer technology and the advent <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Internet has taken the dialectics <strong>of</strong> Marxist<br />

alienation <strong>in</strong>to Baudrillard’s hyperreality. <strong>The</strong><br />

resultant dis<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>of</strong> material production <strong>in</strong>to<br />

communication testifies to the progressive<br />

dematerialization <strong>of</strong> both the productive body<br />

and produced bodies <strong>in</strong> a world <strong>of</strong> entirely<br />

automated factories and “web romance”. In<br />

response to the on-go<strong>in</strong>g disappearance — or<br />

quasi-<strong>in</strong>visibility — <strong>of</strong> the physical body <strong>in</strong> social<br />

realities, a paradoxical and reactionary ‘antivision’<br />

developed <strong>in</strong> contemporary art s<strong>in</strong>ce the early<br />

sixties to re-affirm the materiality <strong>of</strong> the human<br />

MAMMAL THOUGHTS<br />

<strong>The</strong> series Mammal Thoughts explores the question<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> bodily identity <strong>in</strong>terweaved with philosophical self-reflection (the<br />

Cartesian Cogito). Each large format color portrait <strong>in</strong>volved an <strong>in</strong>tercollaborative dialogue between the photographer and<br />

the subject, encourag<strong>in</strong>g the latter to reappropriate his/her own particular understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> bodily representation through<br />

absurdity, absence, humor or eroticism while be<strong>in</strong>g presented as just a body.<br />

Text by Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

6<br />

body and its sensualist primacy <strong>in</strong> the relationship<br />

<strong>of</strong> the subject with the object world. <strong>The</strong> Fluxus art<br />

movement, Robert Morris’ Process Art and his<br />

theorization <strong>of</strong> “Anti-Form” <strong>in</strong> 1968, as well as the<br />

works <strong>of</strong> Arman and Joseph Cornell just to name<br />

a few, are representative <strong>of</strong> that elementary drive<br />

<strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>eteen sixties and seventies art toward crude<br />

materialism and aga<strong>in</strong>st manufactured<br />

aesthetics. <strong>The</strong> performative happen<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong><br />

Carolee Schneemann, Shigeko Kubota and other<br />

first-wave fem<strong>in</strong>ist artists also significantly<br />

contributed to question vision’s naturality and<br />

culturality through their critical positions. In her<br />

1963 <strong>in</strong>augural “Eye/Body” performance,<br />

Schneemann’s exhibit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> her naked body<br />

covered with pa<strong>in</strong>t, grease and other primal<br />

materials suggested an ambiguously embodied<br />

self-envision<strong>in</strong>g, where vision “happened” to be<br />

constituted not only by the seer but also by the<br />

seen. Such preoccupations resonate throughout<br />

the Mammal Thoughts photographic series,<br />

concerned with how vision is subsumed <strong>in</strong>to<br />

materiality. <strong>The</strong> reciprocal exclusion <strong>of</strong> physicality<br />

and identity ultimately grounded my research <strong>in</strong> a<br />

radical scrut<strong>in</strong>y <strong>of</strong> Western culture’s classic m<strong>in</strong>dbody<br />

dualism. My approach to portraiture<br />

reenacts Descartes’ <strong>in</strong>dubitable cogito ergo sum<br />

(I th<strong>in</strong>k therefore I am) <strong>in</strong> the theoretical context<br />

left open by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception. Each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

thirteen photographs compos<strong>in</strong>g the series<br />

portray the same <strong>in</strong>dividual performance — a<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g moment — where <strong>in</strong>dividuals are asked<br />

to reflect <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong> the camera as body-subjects.

Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

Stephanie, Mammal Thoughts, 2005, 30x40 Lightjet pr<strong>in</strong>t © Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

7

My photographic project Mammal Thoughts<br />

strives to represent the human body and<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuality accord<strong>in</strong>g to Merleau-Ponty’s<br />

corporeal phenomenology where the subject’s<br />

ability to envision the world, and to be <strong>of</strong> it, is<br />

recomposed <strong>in</strong> corporeality itself. <strong>The</strong> raw meat<br />

laid out <strong>in</strong> the narrative spaces <strong>of</strong> each<br />

photograph unveils Merleau-Ponty’s flesh <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world, and questions traditional discrim<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

between the subjects’ materiality and that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world.<br />

It has <strong>of</strong>ten been argued that the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> arte povera <strong>in</strong> the gallery space<br />

was a symptomatic consequence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

broaden<strong>in</strong>g importance <strong>of</strong> artistic methodologies<br />

concerned with fem<strong>in</strong>ism, queer theory, poststructuralism<br />

and psychoanalytic theory.<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> that statement’s supposed truth,<br />

the use <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t, poor, and mundane materials has<br />

been promoted s<strong>in</strong>ce the sixties as an orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

medium able to assemble the new abjected and<br />

degraded identities circulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> modern society.<br />

But the “poorness’ revolution” <strong>of</strong> the arts didn’t rise<br />

without effectively transgress<strong>in</strong>g the traditions <strong>of</strong><br />

purity and prudery <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution by<br />

foreground<strong>in</strong>g issues <strong>of</strong> gender and sexuality <strong>in</strong><br />

the art exhibited. More importantly, <strong>in</strong>asmuch as it<br />

symbolically proposed to violate the hermetic<br />

purity <strong>of</strong> the laboratory <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional values, it<br />

signaled the <strong>in</strong>auguration <strong>of</strong> an essential counter<br />

movement from with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> social<br />

control toward the superficial homogeneity and<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uity <strong>of</strong> global consumerism and the aseptic<br />

aesthetic <strong>of</strong> the ever-fashionable self that it<br />

subjugates. To that extent, the use <strong>of</strong> raw meat <strong>in</strong><br />

the Mammal Thoughts photographs certa<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

satisfies a will to distance <strong>in</strong>dividual representation<br />

from portray<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>tegrated Self with<strong>in</strong> social<br />

spaces <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>use materiality. Rather contrarily, it<br />

aims at detach<strong>in</strong>g that mythological narrative <strong>of</strong><br />

consumptive happ<strong>in</strong>ess from the body’s<br />

constitutive relationship with the subject, while<br />

glimps<strong>in</strong>g at the even greater deficit <strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g today between the two. Thus the lack <strong>of</strong><br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> one’s own materiality occupies<br />

a central role <strong>in</strong> the representation <strong>of</strong> each<br />

character <strong>in</strong> the series, allegedly perform<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

paradoxical cogito: to th<strong>in</strong>k that one merely is his<br />

own body. <strong>The</strong> Mammal Thoughts photographs<br />

suggest dialectical possibilities to attempt to<br />

overcome the metaphysical aporia that occupies<br />

the subject’s relationship with his own materiality.<br />

<strong>The</strong> mutual exclusion <strong>of</strong> bodily reality and<br />

self-perception actualized <strong>in</strong> my work recalls the<br />

ever problematic nature <strong>of</strong> any relational<br />

displacement from presentation to representation,<br />

8<br />

as a testimony to Western culture’s m<strong>in</strong>d-body<br />

dualism orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> the 16 th and 17 th century<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d. More specifically, I would like<br />

to briefly refer here to René Descartes’ Meditations<br />

on First Philosophy, whose cogito we already<br />

referred to <strong>in</strong> the present discourse. It is to that<br />

sem<strong>in</strong>al work that we owe the first systematic<br />

account <strong>of</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d-body relationship, historically<br />

emblematized <strong>in</strong> its cornerstone formulae cogito<br />

ergo sum. In the larger metaphysical context <strong>of</strong><br />

this writ<strong>in</strong>g, Descartes was to ultimately<br />

demonstrate the existence <strong>of</strong> God after<br />

establish<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> foundations for scientific<br />

knowledge, and jo<strong>in</strong>tly to fight the obscurantism<br />

and the skepticism <strong>of</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> his time. As the<br />

founder <strong>of</strong> rationalist th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, his demonstration<br />

relied on a particular <strong>in</strong>tellectual process that<br />

Descartes himself co<strong>in</strong>ed “methodical doubt”,<br />

which consisted <strong>in</strong> pos<strong>in</strong>g more and more<br />

powerful skeptical hypotheses <strong>in</strong> order to call <strong>in</strong>to<br />

doubt entire classes <strong>of</strong> knowledge. Hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

elim<strong>in</strong>ated all truths derived from the senses, from<br />

the imag<strong>in</strong>ation and many <strong>of</strong> those which come<br />

from reason, Descartes f<strong>in</strong>ally concluded that<br />

there was one th<strong>in</strong>g he would never be deceived<br />

<strong>in</strong>to doubt<strong>in</strong>g: the certa<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>of</strong> his own existence,<br />

for someth<strong>in</strong>g has to necessarily exist that th<strong>in</strong>ks<br />

and doubts <strong>in</strong> order to be deceived. Thus,<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to Descartes, even the most skeptical<br />

person would have to admit that he is at least a<br />

res cogitans (a th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>in</strong>g). But <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gly and<br />

retrospectively then, all that on which our basic<br />

cognitive Western culture is based would<br />

structurally be our own self-consciousness. As <strong>in</strong><br />

the perspective <strong>of</strong> Descartes’ cogito, all realities<br />

would then <strong>in</strong>deed unmistakably happen to be<br />

just representations. But th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about vision’s<br />

material nature, the fact that the Cartesian m<strong>in</strong>d<br />

<strong>in</strong>trospects the entire world and its sensible<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation through its omnipotent reflection,<br />

eventually synthesiz<strong>in</strong>g not only the body but the<br />

Self, provides his philosophy with a problematic,<br />

de-substantiated vision. For it would then<br />

presuppose a m<strong>in</strong>d without eyes or body, namely<br />

a disembodied vision, which <strong>in</strong> return should be<br />

able to consider one’s own body just as another’s.<br />

If the body resists the m<strong>in</strong>d’s absolute horizon, it<br />

may well be on the contrary because the latter<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>ates with<strong>in</strong> corporeality, as a physical<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> material visibility. However,<br />

refut<strong>in</strong>g Descartes’ idealism leaves one with no<br />

other choice than revers<strong>in</strong>g the terms <strong>of</strong> his<br />

equation. <strong>The</strong>refore, anchor<strong>in</strong>g vision and selfreflection<br />

back <strong>in</strong>to the perceptive materiality <strong>of</strong><br />

one’s body appears necessary. But reencapsulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

vision <strong>in</strong> the body fundamentally<br />

characterizes it as situational and perspectival,

Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

Eric, Mammal Thoughts, 2006, 30x40 Lightjet pr<strong>in</strong>t © Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

9

mean<strong>in</strong>g that there is no vision without viewpo<strong>in</strong>t,<br />

nor without the <strong>in</strong>herent limitation <strong>of</strong> the body’s<br />

horizon. Such an existential reposition<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d and body relationship places physicality at<br />

the center <strong>of</strong> self-reflective activity, where the<br />

bodily be<strong>in</strong>g as both sentient subject and sensible<br />

object becomes nodal, if not <strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable.<br />

Hence corporeality needs to be rethought outside<br />

the m<strong>in</strong>d-body dualism’s artificial split, and away<br />

from a visuality <strong>of</strong> transcendental nature. If, on the<br />

contrary, vision is immanential, always embedded<br />

and related to the physical presence <strong>of</strong> one’s<br />

body, then the paradoxical attempt to reach the<br />

dis<strong>in</strong>carnated po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g one’s body<br />

— that is, be<strong>in</strong>g pure human materiality — sought<br />

by the Mammal Thoughts’ <strong>in</strong>dividuals is<br />

symbolically envisioned as raw meat <strong>in</strong> my<br />

photographs. This ultimate thought, unbounded<br />

from its bodily th<strong>in</strong>ker, not only actualizes its<br />

signification <strong>of</strong> crude physicality <strong>in</strong> the meat, but<br />

also betrays its <strong>in</strong>herent subjective nature <strong>in</strong> it.<br />

Lastly, it seems ironically plausible to consider the<br />

meat as a successful cogito, or <strong>in</strong> other words as<br />

a freed thought now be<strong>in</strong>g able to position itself<br />

before the body <strong>in</strong> order to signify the <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

as itself.<br />

Consequently, the m<strong>in</strong>d and the body<br />

must not be conceived exogenously as two<br />

heterogeneous modes fram<strong>in</strong>g the existential<br />

space <strong>in</strong> which one lives. Because there is but<br />

one topos, our body, <strong>in</strong> which to rearticulate<br />

human be<strong>in</strong>g’s materiality and self-reflectivity, one<br />

must seek a first philosophy where those two<br />

existential extremities meet and dialectically<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrate each other. As a means to further<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>e and circumscribe the theoretical<br />

implications and aesthetic articulations underl<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by such ontological question<strong>in</strong>g through the<br />

present photographic work, one needs to<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigate prospective answers with<strong>in</strong> the writ<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the most significant contributors to<br />

contemporary phenomenology. As <strong>in</strong> fact,<br />

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s theorization <strong>of</strong> a<br />

phenomenological body-subject <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

conceived <strong>of</strong> a notion <strong>of</strong> a pre-l<strong>in</strong>guistic subject,<br />

whose consciousness fundamentally appears<br />

<strong>in</strong>separable and <strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from the<br />

human body.<br />

Paradoxically enough, what is essentially at<br />

stake <strong>in</strong> Merleau-Ponty’s magnum opus<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception isn’t perception per<br />

se, but rather a fundamental reposition<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the<br />

existential subject <strong>in</strong> the world. Historically<br />

associated with the “phenomenological turn” that<br />

occupied European philosophy before the rise <strong>of</strong><br />

structuralism, his understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the subject<br />

radically rejects the metaphysical tradition <strong>of</strong><br />

10<br />

body-m<strong>in</strong>d dualism previously enterta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> our<br />

discussion. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to him, a flawed<br />

<strong>in</strong>tellectualism always outl<strong>in</strong>ed both empiricist<br />

(immanential) and idealist (transcendental)<br />

philosophical projects. It betrayed <strong>in</strong> essence the<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrity, and thus primacy, <strong>of</strong> existential<br />

experience by privileg<strong>in</strong>g one <strong>of</strong> the terms — the<br />

body or the m<strong>in</strong>d — over the other. As a result,<br />

neither the rationalist world apprehended by a<br />

reflect<strong>in</strong>g cogito, nor the objectification realized<br />

through science’s analytical studies succeeded <strong>in</strong><br />

authentically account<strong>in</strong>g for the lived reality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Self. In fact, both methodologies missed the<br />

bear<strong>in</strong>g that firstly conditions them: that existence<br />

comprises only embodied experiences, and<br />

hence that there can only be embodied<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the world. It is thus <strong>of</strong> one ontological<br />

necessity for Merleau-Ponty that the cognitive<br />

subject re<strong>in</strong>tegrates the practical exigencies <strong>of</strong><br />

what he names the body-subject, <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

“rediscover, as anterior to the ideas <strong>of</strong> subject and<br />

object, the fact <strong>of</strong> my subjectivity and the<br />

nascent object, that primordial layer at which<br />

both th<strong>in</strong>gs and ideas come <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g” (Merleau-<br />

Ponty, M. Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception).<br />

Away from any dualistic exploration <strong>of</strong><br />

existence, Merleau-Ponty’s notion <strong>of</strong> the bodysubject<br />

reclaims the perceiv<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>d as an<br />

<strong>in</strong>carnated body, <strong>in</strong>s<strong>of</strong>ar as one accesses the<br />

world only through his body: “I am not <strong>in</strong> front <strong>of</strong><br />

my body, I am <strong>in</strong> it or rather I am it…If we can still<br />

speak <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>in</strong> relation to the<br />

perception <strong>of</strong> one’s own body, we shall have to<br />

say that it <strong>in</strong>terprets itself” (Merleau-Ponty,<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception). What<br />

characterizes the significance <strong>of</strong> the body <strong>in</strong><br />

Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy is its <strong>in</strong>herence to the<br />

world, its embodied state <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g, and closer to<br />

our photographic discourse the very fact that<br />

see<strong>in</strong>g also depends on one’s capacity to be<br />

seen. Indeed for him, subjective vision is<br />

dialectically constituted, just as much as my<br />

engagement <strong>in</strong> the physical world as an<br />

engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the physical world <strong>in</strong> me. Merleau-<br />

Ponty’s view<strong>in</strong>g eye is situated <strong>in</strong> a mov<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

empirical body that, despite its lack <strong>of</strong><br />

identification with the world, is yet <strong>of</strong> the world.<br />

Merleau-Ponty’s denigration <strong>of</strong> Western<br />

philosophy’s ant<strong>in</strong>omical relationship between the<br />

Self and the object world through the <strong>in</strong>carnation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual existence <strong>in</strong>to the body-subject<br />

draws a relational and situational def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge that, while not giv<strong>in</strong>g way to any<br />

materialist or behaviorist philosophy, eludes a<br />

clear frame <strong>of</strong> reference. His reflections <strong>in</strong><br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception are united around<br />

the claim that the lived experience <strong>of</strong> one’s body

Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

George, Mammal Thoughts, 2006, 30x40 Lightjet pr<strong>in</strong>t © Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

11

is foundational <strong>of</strong> human communications, selfidentity<br />

and cognition <strong>in</strong> general. When assert<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that “I am my body” (Merleau-Ponty,<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception), he essentially<br />

means that the practical modes <strong>of</strong> action <strong>of</strong> the<br />

body-subject are <strong>in</strong>discernible from the<br />

perceiv<strong>in</strong>g body-subject, <strong>in</strong> the same way that<br />

the body-subject himself cannot detach his<br />

presence <strong>in</strong> the world from his body: “Inside and<br />

outside are <strong>in</strong>separable. <strong>The</strong> World is wholly <strong>in</strong>side<br />

and I am wholly outside <strong>of</strong> myself” (Merleau-Ponty,<br />

Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception).<br />

What appears central to Merleau-Ponty’s<br />

existential view here is a pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, or<br />

rather as he terms it himself <strong>of</strong> ambiguity, based<br />

on the body’s reversible propensity: its capacity to<br />

be both sentient and sensible, or <strong>in</strong> other words to<br />

be both object <strong>of</strong> the world and subject <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world. But that reversibility <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sically demands<br />

that those two modes <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g never fully<br />

co<strong>in</strong>cide, that they coextend through time, which<br />

clearly entails the two major existential<br />

impossibilities <strong>of</strong> know<strong>in</strong>g oneself absolutely and<br />

<strong>of</strong> objectify<strong>in</strong>g the world totally. As Merleau-Ponty<br />

wrote it, “ambiguity prevails both <strong>in</strong> my perception<br />

<strong>of</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs and <strong>in</strong> the knowledge I have <strong>of</strong> myself”<br />

(Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception),<br />

as “whenever I try to understand myself, the whole<br />

fabric <strong>of</strong> the perceptible world comes too, and<br />

with it come the others who are caught <strong>in</strong> it”<br />

(Merleau-Ponty. Signs). But the uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge we mentioned earlier must not be<br />

understood as its mere condemnation, for if the<br />

empirical and transcendental attitudes are<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itely disclaimed, the body-subject<br />

experiences are nonetheless mean<strong>in</strong>gful <strong>in</strong> a<br />

different way. Through its complex commerce<br />

with the material substance <strong>of</strong> the world, the body<br />

is revealed as one <strong>in</strong>tegral but permeable<br />

medium phenomenally mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the world, as<br />

well as mov<strong>in</strong>g the world <strong>in</strong>to oneself.<br />

This last remark bears a tw<strong>of</strong>old<br />

importance when consider<strong>in</strong>g how the world for<br />

Merleau-Ponty <strong>in</strong>herently co-def<strong>in</strong>es the body and<br />

literally resides <strong>in</strong> it. In reality, the assertion that “the<br />

world is wholly <strong>in</strong>side and (that) I am wholly outside<br />

<strong>of</strong> myself” not only practically characterizes the<br />

way the subject <strong>in</strong>teracts with the world and gets<br />

to know it, but it also postulates a world no longer<br />

foreign and absolutely separated from the<br />

subject. <strong>The</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> the mutual exclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

self and world entailed <strong>in</strong> the abandonment <strong>of</strong><br />

the dualist conception <strong>of</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d and body will <strong>in</strong><br />

fact lead Merleau-Ponty to conceive <strong>of</strong> material<br />

reality as flesh. This notion is central to my<br />

upcom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> the Mammal Thought<br />

series, where it symbolizes the carnal <strong>in</strong>tentionality<br />

12<br />

that the portrayed <strong>in</strong>dividuals try to stand for.<br />

Yet, “what enables us to center our existence is<br />

also what prevents us from center<strong>in</strong>g it<br />

completely, and the anonymity <strong>of</strong> our body is<br />

<strong>in</strong>separably both freedom and servitude”<br />

(Merleau-Ponty, Signs). <strong>The</strong>re is ambiguity precisely<br />

because we are not capable <strong>of</strong> disembodied<br />

reflection upon our own bodies. For that reason,<br />

Merleau-Ponty considers the body as our means<br />

<strong>of</strong> communication with the world: “Th<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world must have mean<strong>in</strong>g”, he writes, “not<br />

because we have signs but because we have<br />

bodies” (Merleau-Ponty, Signs). Hence, by<br />

gestur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to space, one br<strong>in</strong>gs a mean<strong>in</strong>gful<br />

world <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> central role played by the<br />

mov<strong>in</strong>g body <strong>in</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g construction is such that<br />

it seems to constitute the subject’s closest<br />

relationship to mean<strong>in</strong>g itself, to the po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong><br />

conceiv<strong>in</strong>g a genealogy <strong>of</strong> language based on<br />

what he calls the gestural sign. <strong>The</strong> body analogy<br />

through the concept <strong>of</strong> gesture br<strong>in</strong>gs a whole<br />

different aesthetic <strong>of</strong> communication <strong>in</strong>to play,<br />

where visual perception models verbal and<br />

pictorial significations. In fact, Merleau-Ponty<br />

consistently compares the production and<br />

reception <strong>of</strong> images to the production and<br />

reception <strong>of</strong> gestures: “Words and Images”, he<br />

says, “emerge from me like gestures” (Merleau-<br />

Ponty, Signs).<br />

By rearticulat<strong>in</strong>g the constitution <strong>of</strong> the Self<br />

and the very process <strong>of</strong> signification <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

bodily subject, Merleau-Pontian phenomenology<br />

manifests untapped perspectives to approach<br />

materiality <strong>in</strong> general, and to question its uses and<br />

representations <strong>in</strong> plastic and visual arts. In his<br />

unf<strong>in</strong>ished writ<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible,<br />

Merleau-Ponty draws on the ontological<br />

implications necessitated by his th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual as body-subject. Our embodied<br />

subjectivity is never purely located <strong>in</strong> either our<br />

body or the world, but rather <strong>in</strong> the correlation <strong>of</strong><br />

those, namely, <strong>in</strong> Merleau-Ponty’s own<br />

term<strong>in</strong>ology, where the l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> the chiasm they<br />

constitute <strong>in</strong>tersect with one another: “<strong>The</strong>re is a<br />

body <strong>of</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d, and a m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> the body and a<br />

chiasm between them” (Merleau-Ponty. <strong>The</strong><br />

Visible and the Invisible), he says. <strong>The</strong> chiasmic<br />

figure is yet the pr<strong>in</strong>cipled scheme <strong>of</strong> subjectivity<br />

for Merleau-Ponty. As the rul<strong>in</strong>g ontological motif<br />

that testifies that m<strong>in</strong>d and body, subject and<br />

object, self and world are but an encroachment,<br />

the chiasm dialectically reflects the bodysubject’s<br />

reversibility and its correspond<strong>in</strong>g<br />

ambiguity onto the world, which is thus theorized<br />

as flesh — or flesh <strong>of</strong> the world. As he makes it<br />

clear, “the thickness <strong>of</strong> the body, far from rival<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the world, is on the contrary the sole

means I have to go unto the heart <strong>of</strong> the th<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

by mak<strong>in</strong>g myself a world and by mak<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

flesh” (Merleau-Ponty, <strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible).<br />

However abstract <strong>in</strong> its formulation,<br />

Merleau-Ponty ‘s work<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>of</strong> materiality as flesh<br />

must not be either literally or poetically<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpreted. Unequivocally, the flesh <strong>of</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs is<br />

relationally constituted with<strong>in</strong> the perceiv<strong>in</strong>g bodysubject,<br />

permeat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ner recesses <strong>of</strong> his<br />

subjectivity “so that the seer and the visible<br />

reciprocate one another… It is this Visibility, this<br />

generality <strong>of</strong> the Sensible <strong>in</strong> itself, this anonymity<br />

<strong>in</strong>nate to Myself that we have previously called<br />

flesh” (Merleau-Ponty, <strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible).<br />

This “anonymity <strong>in</strong>nate to myself”, that<br />

unseen antruthful material belong<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> me-as-abody<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the world, this one reflection <strong>of</strong> my<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uity and unity with it that only the Other<br />

realizes, but that I always miscarry by th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g I am<br />

contiguous to the world as a subject, means the<br />

flesh. As such, it also is a gap (écart, <strong>in</strong> French),<br />

visible everywhere <strong>in</strong> the world between my own<br />

corporeality and me as a subject. Measures <strong>of</strong><br />

this gap only exist <strong>in</strong> my self-reflection, and <strong>in</strong> my<br />

projection <strong>of</strong> a world <strong>of</strong> objects around me. My<br />

body ignores it, for it knows pre-reflectively — that<br />

is perceptually — how to be <strong>in</strong> equilibrium as a<br />

mortal and temporal be<strong>in</strong>g. But <strong>in</strong>s<strong>of</strong>ar as I can’t<br />

reflect on my body’s pre-reflective knowledge, my<br />

body rema<strong>in</strong>s unknown to myself albeit present to<br />

itself: it is phenomenally <strong>in</strong>considerable<br />

(“<strong>in</strong>figurable”, <strong>in</strong> French). And yet, as an earlier<br />

quote from Merleau-Ponty already suggested, it is<br />

both what conditions my freedom and my<br />

servitude: it is my liberty to be <strong>in</strong> the world (“être au<br />

monde”, <strong>in</strong> French), to move <strong>in</strong> it and to act upon<br />

it. Inasmuch as it situates me <strong>in</strong> time and space, it<br />

<strong>in</strong>tercedes for my be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the world, and<br />

therefore alienates me to be with it while lead<strong>in</strong>g<br />

me astray from my immediacy and my own<br />

presence. This is my ambiguity, and only<br />

ambiguously am I given to myself: “I know myself<br />

only <strong>in</strong>s<strong>of</strong>ar as I am <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> time and <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world, that is, I know myself only <strong>in</strong> my ambiguity”<br />

(Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception).<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no elucidat<strong>in</strong>g it, one can only know it,<br />

and thus only by accept<strong>in</strong>g my ambiguity — not<br />

co<strong>in</strong>cid<strong>in</strong>g with my body, liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the chiasmic<br />

permanence <strong>of</strong> its écart, namely be<strong>in</strong>g a bodysubject<br />

— can I come <strong>in</strong>to terms with my own<br />

f<strong>in</strong>itude.<br />

With those bare existential aspects <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d,<br />

one cannot but th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> the raw meat displayed <strong>in</strong><br />

each photograph <strong>of</strong> the Mammal Thoughts series<br />

as a pictorial equivalent for Merleau-Ponty’s<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> flesh. Several other fundamental<br />

connections re<strong>in</strong>force such a read<strong>in</strong>g, hav<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

13<br />

series firstly function as a portrayal <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

cogitat<strong>in</strong>g, and even more so reflect<strong>in</strong>g on the<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g just their own bodies.<br />

Consequently, the series’ photographic<br />

momentum is essentially about grasp<strong>in</strong>g bodysubjects<br />

approach<strong>in</strong>g their elemental gap, or just<br />

the same constantly fall<strong>in</strong>g on one side <strong>of</strong><br />

Merleau-Ponty’s Chiasm. Each <strong>in</strong>dividual has<br />

therefore been “seen”, mean<strong>in</strong>g here “seen not<br />

see<strong>in</strong>g”, while the camera presence subjected<br />

them to the very vision they were seek<strong>in</strong>g, and<br />

reflected their question as to who and how they<br />

are manifestly, or one should say phenomenally,<br />

as f<strong>in</strong>ished subjects: mammal th<strong>in</strong>kers,<br />

chiasmically photographed, absorbed <strong>in</strong> the<br />

unth<strong>in</strong>kable reflection <strong>of</strong> pieces <strong>of</strong> meat that<br />

trapped them and freed them all <strong>in</strong> the same<br />

gesture.<br />

<strong>Visual</strong>ly speak<strong>in</strong>g, the raw meat “appears”<br />

<strong>in</strong> the true Heideggerian sense <strong>of</strong> Ersche<strong>in</strong>ung —<br />

apparition — from the material world to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g subjectivity. It is exactly “what” the<br />

body-subject can’t reflect — or measure — <strong>of</strong><br />

himself while bent on itself. Or <strong>in</strong> other words, it is<br />

“where” the m<strong>in</strong>d slips and falls back <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

world, aga<strong>in</strong> away from itself. As the lexical<br />

symbol <strong>of</strong> Merleau-Ponty’s flesh <strong>of</strong> the visible, the<br />

meat represents what is yet <strong>in</strong>visible <strong>in</strong> each<br />

portrait: the co<strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> the thought <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

material with the envision<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> that thought.<br />

Importantly, the theoretical role assumed<br />

by the meat <strong>in</strong> this work echoes the larger<br />

problematic <strong>of</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g visuality <strong>in</strong> its<br />

dialectical relationship with materiality, as found <strong>in</strong><br />

Merleau-Ponty’s later aesthetic philosophy. As we<br />

now know, he conceived <strong>of</strong> visual depiction as<br />

grounded <strong>in</strong> a complex engagement with the<br />

material environment. But the constitutive position<br />

<strong>of</strong> the seer is fundamentally emphasized beyond<br />

pure perception <strong>in</strong> <strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible,<br />

along the idea that “the thickness <strong>of</strong> flesh<br />

between the seer and the th<strong>in</strong>g is constitutive for<br />

the th<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> its visibility as for the seer <strong>of</strong> his<br />

corporeality” (Merleau-Ponty. <strong>The</strong> Visible and the<br />

Invisible). In other words, th<strong>in</strong>gs are only visible for<br />

an embodied subject, which <strong>in</strong> return gives the<br />

world its visibility. Clearly, there is no visibility, no<br />

tangibility nor sensibility without a be<strong>in</strong>g-sensible, a<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g-tangible and a be<strong>in</strong>g-visible. But the<br />

necessary condition and mutual condition<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

materiality is, that co-found<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> co<strong>in</strong>cidental<br />

flesh, appears here most ambiguously as visuality.<br />

For if corporeality really conditions the visibility <strong>of</strong><br />

the world <strong>in</strong>deed reciprocally the significance <strong>of</strong><br />

see<strong>in</strong>g is to be found <strong>in</strong> the materiality <strong>of</strong> the seer.<br />

However, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Merleau-Ponty and his<br />

theorization <strong>of</strong> the body-subject, subjectivity is

Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

Daehwan, Mammal Thoughts, 2005, 30x40 Lightjet pr<strong>in</strong>t © Bastien Desfriches Doria<br />

14

constitutionally unable to embrace its bodily<br />

condition, and is thus condemned to existential<br />

ambiguity. What is then central to the writ<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible is the argument, close<br />

to Heidegger’s ontology, that we need to re<strong>in</strong>terrogate<br />

our visual understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the world<br />

on the premise that ambiguity necessarily prevails<br />

<strong>in</strong> it. <strong>The</strong> meat visible <strong>in</strong> the photographs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mammal Thoughts series embeds such questions.<br />

In fact, it literally asks and answers them<br />

chiasmically, <strong>in</strong> accordance with one’s decision<br />

to read it from the portrayed <strong>in</strong>dividual’s<br />

perspective —where the meat manifests the<br />

world and the subject’s <strong>in</strong>visibility to itself — or on<br />

contrary if one <strong>in</strong>vests the image as a<br />

representation, pound<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>dexical weight <strong>of</strong><br />

the meat on ambiguous metaphorical mean<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Even if Merleau-Ponty’s notion <strong>of</strong> the bodysubject<br />

and his emphasis upon a pre-reflective<br />

body don’t advocate a return to simple and<br />

spontaneous relations with the physical world, or<br />

to put it differently don’t exalt a nostalgic desire to<br />

rejo<strong>in</strong> some primordial <strong>in</strong>herence <strong>in</strong> Be<strong>in</strong>g, his<br />

“<strong>in</strong>direct” ontology <strong>of</strong> the Self doesn’t resolve the<br />

difficult question <strong>of</strong> how one needs to <strong>in</strong>terpret his<br />

body’s materiality. If one cannot understand what<br />

roots existence and thus what provides mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to it, except through the fundamental<br />

communication — if not stasis — <strong>of</strong> his body with<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> universal concreteness, a non-space <strong>of</strong><br />

philosophy may be legitimately called upon to fill<br />

Merleau-Ponty’s gap. In the perspective <strong>of</strong> free<strong>in</strong>g<br />

oneself from what he calls “the paradox <strong>of</strong><br />

transcendence <strong>in</strong> immanence”, the temptation to<br />

simply abdicate the seem<strong>in</strong>gly secondary term <strong>of</strong><br />

the body-subject — be<strong>in</strong>g a subject — and opt<br />

for a radical bodily ontogenesis is not <strong>in</strong>significant.<br />

But the result<strong>in</strong>g existentiality, filled with carnal<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g and constituted out <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tercorporeality<br />

<strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersubjectivity, would however<br />

presuppose the annihilation <strong>of</strong> self-reflexivity, and<br />

thus the death <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuality. Such a radical<br />

perspective certa<strong>in</strong>ly doesn’t concern my present<br />

work, but its pictur<strong>in</strong>g has consistently <strong>in</strong>spired<br />

controversial works s<strong>in</strong>ce the very beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

photography, ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> the asubjective directions<br />

<strong>of</strong> pornography (from Auguste Belloc to C<strong>in</strong>dy<br />

Sherman’s “Sex Pictures”) and morbidity (from<br />

Weegee to Joel-Peter Witk<strong>in</strong>).<br />

Historically, the body as either object or subject<br />

<strong>of</strong> visual <strong>in</strong>terpretation has persistently<br />

foregrounded explorations <strong>of</strong> the fundamental<br />

relationship between physicality and Self and their<br />

<strong>in</strong>extricable <strong>in</strong>terdependency. <strong>The</strong> notions <strong>of</strong><br />

‘be<strong>in</strong>g’ and the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> ‘body’ have only<br />

recently extended <strong>in</strong>to the psychoanalytic and<br />

the l<strong>in</strong>guistic arenas, <strong>in</strong>terrogat<strong>in</strong>g unsuspected<br />

15<br />

complexities beyond the body-m<strong>in</strong>d dualism<br />

traditionally prevail<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Western culture’s<br />

philosophical and representational def<strong>in</strong>itions.<br />

Even the recent post-structuralist <strong>in</strong>cursions<br />

<strong>in</strong> photography didn’t fundamentally change our<br />

conception <strong>of</strong> the body, while nonetheless<br />

acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g its deconstructive nature through<br />

the subject’s historicity and the social prism <strong>of</strong><br />

sexuality, as <strong>in</strong> the works <strong>of</strong> Robert He<strong>in</strong>ecken or<br />

Richard Hamilton. <strong>The</strong> ontological wonder at the<br />

body and at its ambiguous belong<strong>in</strong>g to both<br />

subjectivity and the object world hasn’t changed<br />

or been resolved. Aside from early k<strong>in</strong>esthetic,<br />

anatomical and pseudo-anthropological uses <strong>of</strong><br />

photography, and not consider<strong>in</strong>g the modernist<br />

lyricism <strong>of</strong> formal purity and its long l<strong>in</strong>eage <strong>of</strong><br />

practitioners (up to Lucien Clerge, Barbara Crane<br />

and Ralph Gibson), body representations <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

branched between morbid, sexual or racial<br />

convolutions (Hans Bellmer, Robert Mapplethorpe,<br />

Lynn Davis), social observation or conceptual reappropriation<br />

(Humberto Rivas, R<strong>in</strong>eke Dijkstra,<br />

Bruce Nauman), a literal adherence to the body’s<br />

material essence <strong>of</strong> hair, flesh and sk<strong>in</strong> (Robert<br />

Davies, Yves Trémor<strong>in</strong>, John Coplans, Holly Wright),<br />

and eerie scenarios <strong>in</strong>herited from the Dada and<br />

Surrealist traditions (from Oscar Gustave Rejlander<br />

to Jerry Uelsmann), the latter group ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

succumb<strong>in</strong>g to the great temptation <strong>of</strong><br />

dematerializ<strong>in</strong>g the body toward its identification<br />

with unconscious, soul or m<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

<strong>The</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> such an analytical — albeit<br />

arbitrary and probably too rigidly categoriz<strong>in</strong>g —<br />

account <strong>of</strong> the photographic body, is that the<br />

fabric <strong>of</strong> vision still problematically relies on the<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d-body dualism, which <strong>in</strong> the philosophical<br />

perspective <strong>of</strong> the Mammal Thoughts doesn’t<br />

co<strong>in</strong>cide with the <strong>in</strong>tegrative fabric <strong>of</strong> the body’s<br />

reality. However, few artists successfully managed<br />

to <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>in</strong> their work the body’s ontological<br />

and ethical ambivalence as both subject and<br />

object <strong>of</strong> the world, and so not only developed<br />

an entirely different aesthetic <strong>of</strong> that relationship,<br />

but more importantly <strong>in</strong>scribed its viewpo<strong>in</strong>t upon<br />

the viewer’s position. Lucas Samaras, who<br />

consistently embedded the body image with<strong>in</strong><br />

the material texturality <strong>of</strong> the Polaroid pr<strong>in</strong>t through<br />

his manipulation <strong>of</strong> the film’s layers, appears to<br />

me as one <strong>of</strong> them. <strong>The</strong> fact that most <strong>of</strong> his work<br />

consists <strong>in</strong> self-portraits literally illustrates my<br />

argument for an envision<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the subject by the<br />

seer as neither simply corporeal nor<br />

transcendental. Photography here embeds the<br />

artist’s impossible vision <strong>of</strong> a disembodied selfreflection,<br />

what Merleau-Ponty would term a<br />

hyper-reflection, that same existential modality <strong>of</strong><br />

perception that the characters <strong>of</strong> the Mammal

Thoughts series actualize by th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> themselves<br />

as bodies.<br />

Francesca Woodman’s work, generally<br />

speak<strong>in</strong>g, as well as Arno-Rafael M<strong>in</strong>kk<strong>in</strong>en’s “Body<br />

Land” series both represent other significant<br />

photographic testimonials <strong>of</strong> the common<br />

encroachment <strong>of</strong> the body onto the material<br />

substance <strong>of</strong> the world. M<strong>in</strong>kk<strong>in</strong>en chose to<br />

explore natural sett<strong>in</strong>gs to foreground his<br />

corporeal <strong>in</strong>herency to wilderness’ open be<strong>in</strong>g. His<br />

idea that “we are <strong>in</strong> the same world but <strong>in</strong><br />

different landscapes” (M<strong>in</strong>kk<strong>in</strong>en, A. Body Land)<br />

resituates the body’s dialectical relationship to Self<br />

and world with<strong>in</strong> the quest <strong>of</strong> its ontological<br />

envision<strong>in</strong>g. M<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>nen th<strong>in</strong>ks <strong>of</strong> the body as be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

co-constitutive <strong>of</strong> landscape vision, as its<br />

necessary material provenance.<br />

<strong>The</strong> works <strong>of</strong> Samaras, Woodman and<br />

M<strong>in</strong>kk<strong>in</strong>en are all exemplary def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>of</strong> selfportraiture<br />

as a reflective <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

subject upon his presence or appearance <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world. As such, they entail crucial conceptual and<br />

critical resonances with the Mammal Thoughts<br />

series. <strong>The</strong> imperative question<strong>in</strong>g carried out <strong>in</strong><br />

any self-figuration def<strong>in</strong>itely underl<strong>in</strong>es the human<br />

need to mirror one’s factuality when fac<strong>in</strong>g<br />

existential doubt. What is then asked <strong>of</strong> the<br />

photograph <strong>in</strong> a self-portrait is to provide a coobjective<br />

perception <strong>of</strong> oneself <strong>in</strong> the world, so<br />

that one is able to see himself as objectively as<br />

another; namely, to be both seer and seen,<br />

object and subject <strong>of</strong> that perception.<br />

Consequently, the photographic self-portrait is<br />

always cogitatively designed on a first literal level<br />

<strong>of</strong> significance. But unlike subjectivity’s diegetic<br />

temporality <strong>in</strong> actual life, its perception has been<br />

discont<strong>in</strong>ued from the perceived object and<br />

therefore constitutes a reported experience. It is<br />

thus a product, as reflection or imago, <strong>of</strong> an<br />

elusive self-reflection owned by the world. As a<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipial remedy, the Mammal Thoughts’ series<br />

allowed for a resynchronization <strong>of</strong> the cogitative<br />

experience and <strong>of</strong> its witness<strong>in</strong>g, while<br />

photograph<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals engaged <strong>in</strong> the active<br />

doubt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> themselves as anyth<strong>in</strong>g else than<br />

bodies. <strong>The</strong> displacement from self-portraiture to<br />

portraiture redistributed the subjective and<br />

objective <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>of</strong> the real <strong>in</strong> accordance<br />

with a diachronic world composed <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>tersubjective relationships. If <strong>in</strong>deed the<br />

portray<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a self-reflect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual by another<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual guarantees an <strong>in</strong>tegral perceptive<br />

experience <strong>of</strong> self-perception, s<strong>in</strong>ce what is thus<br />

depicted isn’t a differed and reflective selfreflection<br />

<strong>of</strong> the photograph’s subject but the<br />

objective and lived experience <strong>of</strong> another, the<br />

Mammal Thoughts series can therefore be<br />

16<br />

understood as the true envision<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a<br />

community <strong>of</strong> cogitos made visible by virtue <strong>of</strong><br />

the photographer’s existence. However, the<br />

revealed <strong>in</strong>terdependence between photography<br />

and the photographer’s existence cannot provide<br />

any conclusion as to know exactly what the<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g photographs stand for. <strong>The</strong>y could<br />

represent the photographer’s shared historicity <strong>of</strong><br />

yet authentic <strong>in</strong>dividual self-reflections, <strong>in</strong> which<br />

case the photographer’s consciousness would<br />

then become the true sensible photographic<br />

material. If on the other hand they were not about<br />

the photographer’s constitutive co-presence, the<br />

photographs could then plausibly uncover<br />

portraiture as a successful monstration <strong>of</strong> selfreflectiveness.<br />

But <strong>in</strong> that case, the visual criteria<br />

evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the degree to which self-reflection<br />

occurs or not are not identifiable. Moreover,<br />

see<strong>in</strong>g oneself as his own body from the viewpo<strong>in</strong>t<br />

<strong>of</strong> another subject would presuppose a sort <strong>of</strong><br />

projection, if not dis<strong>in</strong>carnat<strong>in</strong>g. If so, the visibility<br />

<strong>of</strong> such a phenomenon would problematically<br />

not belong to any physical subject, echo<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Merleau-Ponty’s enigmatic say<strong>in</strong>g that “Man is not<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the body” (Merleau-Ponty. <strong>The</strong> Visible<br />

and the Invisible).<br />

Bibliography<br />

Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham, Imogen. On the Body. Boston, Bulf<strong>in</strong>ch Press, 1998.<br />

Descartes, René. Meditations on First Philosophy. Indianapolis, Hackett Pub.<br />

Co, 1979.<br />

Ew<strong>in</strong>g, A., William. Body : photographs <strong>of</strong> the human form. San Francisco,<br />

Chronicle Books, 1994.<br />

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology <strong>of</strong> Perception. London, Routledge<br />

and Kegan Paul, 1962.<br />

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Signs. Evanston, Northwestern University Press,<br />

1964.<br />

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. <strong>The</strong> Visible and the Invisible. Evanston,<br />

Northwestern University Press, 1964.<br />

M<strong>in</strong>kk<strong>in</strong>en, Arno Rafael. Body Land. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C., Smithsonian<br />

Institution Press, 1999.<br />

Schneider, Rebecca. <strong>The</strong> Explicit Body <strong>in</strong> Performance. New York, Routledge,<br />

1997.<br />

Towsend, Chris. Vile bodies : photography and the crisis <strong>of</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g. Munich-<br />

New York, Prestel-Verlag, 1998.<br />

Wolf, Sylvia. Dieter Appelt. Chicago, Art Institute <strong>of</strong> Chicago Museum Shop,<br />

1994.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Bastien Desfriches Doria was born <strong>in</strong> Paris, where he used to live<br />

and work before mov<strong>in</strong>g to America <strong>in</strong> 1999 to study Photography. In France,<br />

Bastien earned both a degree <strong>in</strong> Philosophy and <strong>in</strong> Information &<br />

Communication Sciences. Bastien earned an MFA <strong>in</strong> Photography at the<br />

Southern Ill<strong>in</strong>ois University at Carbondale <strong>in</strong> May 2006 and has been work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as an assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Digital Imag<strong>in</strong>g and Photography at Governors<br />

State University s<strong>in</strong>ce September 2006.

I<br />

ntroduction: Ceramic Conta<strong>in</strong>ers, Fleshy<br />

Forms, and <strong>Meat</strong>y Media<br />

<strong>Meat</strong> imagery has appeared <strong>in</strong> various works <strong>of</strong><br />

art dat<strong>in</strong>g back to Paleolithic cave pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs. <strong>The</strong><br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> animals and images <strong>of</strong> fleshy,<br />

bloody meat have appeared <strong>in</strong> various pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

draw<strong>in</strong>gs, and sculptures s<strong>in</strong>ce ancient times,<br />

which document, imag<strong>in</strong>e, and critique<br />

carnivorous practices. While surrealist pa<strong>in</strong>ter<br />

Salvador Dali reportedly wished to be a cook<br />

before he ever hoped to be an artist, potter-poet<br />

Mary Carol<strong>in</strong>e (“M.C.”) Richards once<br />

commented “the way a man eats d<strong>in</strong>ner is<br />

political.” In terms <strong>of</strong> its roles <strong>in</strong> food<br />

consumption, ceramic art is perhaps uniquely<br />

generative <strong>of</strong> various meat metaphors among<br />

other media. This dist<strong>in</strong>ction arises from the fact<br />

that clay can embody themes, textures, and<br />

images <strong>of</strong> meat, and can also conta<strong>in</strong> actual<br />

meat products. Archaeologists have also<br />

identified traces <strong>of</strong> animal fat dat<strong>in</strong>g back to<br />

Mycenaean ceramic wares, provid<strong>in</strong>g historical<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation about eat<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>of</strong> the past.<br />

Ceramic majolica ware and puzzle mugs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

American Art and Craft Movement employed<br />

animals such as rabbits or snakes as accents on<br />

functional serv<strong>in</strong>g ware. Ceramic art straddles the<br />

divide <strong>of</strong> functional and purely aesthetic art<br />

objects from pottery to ceramic sculpture. This<br />

article will address meat themes <strong>in</strong> contemporary<br />

clay art that relates to various representations <strong>of</strong><br />

consumption, sexuality, and commodification.<br />

17<br />

FLESH-POTS AND<br />

CLAY BODIES<br />

In this article, Courtney Lee Weida explores art practices <strong>of</strong> ceramics relat<strong>in</strong>g to themes <strong>of</strong> flesh and<br />

consumption. Beyond ceramic sculptures <strong>of</strong> animals and vessels used to store and serve meat, there are subtle<br />

themes and symbols <strong>of</strong> animals and flesh surround<strong>in</strong>g the clay medium.<br />

Text by Courtney Lee Weida<br />

<strong>The</strong> Clay Body, Sexual Bodies, and<br />

Gendered, Liv<strong>in</strong>g Vessels<br />

Clay has been connected to human bodies and<br />

flesh throughout many cultures and traditions. <strong>The</strong><br />

form <strong>of</strong> pots can echo the curves and functional<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> human bodies. As potters, we speak <strong>in</strong><br />

physical references to the body and the pot (“lip,”<br />

“foot,” “belly,” and “shoulder” <strong>of</strong> the vessel). British<br />

potter Kate Malone <strong>in</strong>vites the associations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

shapes and curves <strong>of</strong> her ceramic forms to that <strong>of</strong><br />

a baby and to the backs <strong>of</strong> children’s knees. Clary<br />

Illian (1999) has noted the shared qualities<br />

between pots and people <strong>in</strong> that both have an<br />

axial symmetry and are types <strong>of</strong><br />

vessels/conta<strong>in</strong>ers, while Marguerite Wildenha<strong>in</strong><br />

(1962) has written that the potter “creates pots<br />

after [his/her] own image” (p. 140). It is also<br />

possible to compare clay to human sk<strong>in</strong> (Mathieu,<br />

2008), or to recognize the vessel symbolically as<br />

relat<strong>in</strong>g to life-giv<strong>in</strong>g food, water, and the womb.<br />

Pueblo potters, such as Stella Shutiva (1987),<br />

describe relationships between the pot and the<br />

potter, not<strong>in</strong>g that some pots by men are larger<br />

and shaped like their bodies, while some women’s<br />

pots are plumped as their bodies are. (qtd. <strong>in</strong><br />

Trimble, 2007, p. 14). This po<strong>in</strong>ts out that our own<br />

physicality as gendered makers can directly<br />

and/or subtly impact the ways <strong>in</strong> which we use our<br />

hands and m<strong>in</strong>ds to shape pots.<br />

V<strong>in</strong>centelli (2000) has observed the<br />

commonly held belief that pottery was historically<br />

“an exclusively female activity” so that work<strong>in</strong>g

Kate Malone<br />

Pumpk<strong>in</strong> Forms, 2008 © Kate Malone<br />

18

with clay becomes a ‘naturalized’ activity l<strong>in</strong>ked to<br />

females.” Yet she argues that “such roles are not<br />

dictated by nature but by culture and the result <strong>of</strong><br />

choices that particular groups have made.” (p.<br />

15). Moira Gatens (1995) also writes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

generative symbolism <strong>of</strong> women’s bodies: “the<br />

female body, <strong>in</strong> our culture, is seen and no doubt<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten ‘lived’ as an envelope, vessel or receptacle”<br />

(p. 41). Certa<strong>in</strong>ly, this emphasizes the unique<br />

capacity <strong>of</strong> the female body to undergo<br />

childbirth and bear life just as pots can hold<br />