Metropolitan Lines Issue 2 - Brunel University

Metropolitan Lines Issue 2 - Brunel University

Metropolitan Lines Issue 2 - Brunel University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

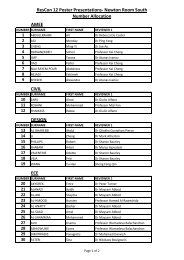

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

1

Summer 2008<br />

FICTION<br />

POSTGRADUATES<br />

Ben Hart 3 World Gone Wrong<br />

Carolyn Skelton 8 Parting Gift<br />

Jo Hurst 10 Hodge<br />

Johanna Yacoub 12 Magilligan<br />

Kate Simants 21 Canal<br />

Perry Bhandal 24 Chicken Jack<br />

Ali Sheikholeslami 35 Paradise, Etc.<br />

FACULTY<br />

William Leahy 38 Emotional Spaceman<br />

John West 42 December 1945...<br />

UNDERGRADUATES<br />

Laura Brown 43 A Lesson Learned<br />

Maria Papacosta 53 Piano<br />

POETRY<br />

UNDERGRADUATES<br />

Marc Spencer 11 Pantoum - The Prophet<br />

Kerry Williams 13 Decadence in the Bathroom<br />

13 Been There, Done That<br />

Emanuele Libertini 8 Pure Research<br />

Mark Woollard 27 The Snail<br />

Jean-David Beyers 29 Thirteen Ways of Looking<br />

at Scissors<br />

32 Filth<br />

Maria Ridley 39 Weeping Woman<br />

45 CC’s<br />

Kerry Williams 48 Paranoia<br />

Shane Jinadu 15 Scarf Me Up<br />

15 Johnny<br />

Marc Spencer 11 Haiku<br />

Visit us on-line:<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong><br />

http://arts.brunel.ac.uk/gate/ml/index<br />

<strong>Brunel</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

http://www.brunel.ac.uk/<br />

The Department of English at <strong>Brunel</strong> <strong>University</strong>, School of Arts<br />

http://www.brunel.ac.uk/about/acad/sa/artsub/english<br />

2<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong><br />

Summer 2008<br />

Editors:<br />

David Fulton<br />

Robert Stamper<br />

Subediting, Layout and Formatting:<br />

Samuel Taradash<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> is the literary<br />

magazine of <strong>Brunel</strong> <strong>University</strong>’s School<br />

of Arts. It exists to showcase the<br />

creative writing, prose and poetry of<br />

students, faculty and staff connected to<br />

the School of Arts at <strong>Brunel</strong> <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Questions, comments or submissions<br />

are welcome, and should be sent to<br />

david.fulton@brunel.ac.uk<br />

Any submissions should be sent as<br />

attachments to e-mail in the form of<br />

.doc or rtf files. Please, check your<br />

spelling and grammar before sending.<br />

The copyrights of all works within are held by their<br />

respective authors. All photographs by Samuel<br />

Taradash, except for page 42, which was was<br />

first published anonymously in the Soviet Journal<br />

Ogonyok, and is currently in the public domain.<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Contents<br />

Editorial Staff

World Gone Wrong<br />

Ben Hart<br />

1. Trying to get to Heaven<br />

The rain slid cautiously down<br />

the angel’s faces, dripping off<br />

their noses and falling to the floor.<br />

Below them a lone hobo sought<br />

shelter within the church that they<br />

guarded, his knocking echoing out<br />

dully through the empty building.<br />

Bemoaning the lack of response<br />

from within the church, the hobo<br />

brushed his soaking hair away from<br />

his face and staggered out into the<br />

churchyard. Pulling his battered<br />

coat around himself as tightly as it<br />

would go, he lay down on a sodden<br />

bench and did his best to sleep.<br />

The night was a bitter one and<br />

sleep did not come easily to the<br />

hobo, but he was exhausted from<br />

the hardships of the day and<br />

eventually it took him, wrenching<br />

him away from the world and into a<br />

wholly better one of his own<br />

devising. For the next three hours<br />

he drifted in and out of<br />

consciousness, hearing the tongues<br />

of angels and men singing in unison<br />

to a tune that his mind couldn’t<br />

place.<br />

Gradually the music began to tail<br />

off. Then it stopped altogether. The<br />

hobo’s eyes snapped open and he<br />

saw the face of a policeman peering<br />

down into his own.<br />

‘Come on you, on your bike!’<br />

The hobo rolled off the bench<br />

and rubbed his bleary eyes.<br />

‘I need to speak with the<br />

Reverend,’ he said. ‘Then I’ll be on<br />

my way’.<br />

‘I’m sure the Reverend has better<br />

things to do than tend to the likes of<br />

you!’ boomed the policeman. He<br />

grabbed the hobo roughly by the<br />

shoulder and shoved him in the<br />

direction of the church gates.<br />

‘I have as much right to be here<br />

as anyone!’ protested the hobo,<br />

gazing up pleadingly at the concrete<br />

angels that towered above him.<br />

‘Sleeping rough on church<br />

property is against the law. I’m<br />

obliged to move you on.’<br />

‘Was Jesus himself not an<br />

outlaw?’<br />

***<br />

2. My Name Is Nobody<br />

My mind’s a mess. Congested.<br />

Like a town centre in<br />

desperate need of a bypass. I stare<br />

out the window, notepad in hand,<br />

and chew at the skin around my<br />

well-bitten nails. It’s a fine old day<br />

outside: sunshine mingling sociably<br />

with a sweeping wind and deft<br />

flakes of snow. It’s the kind of<br />

weather that would usually sound<br />

poetic however you described it, but<br />

today my brain just isn’t up to the<br />

challenge. It blanks me, cutting my<br />

prose off before I’ve even written<br />

anything. Sighing, I clamber up<br />

from my seat and make coffee –<br />

black, no sugar. The caffeine does<br />

its best to stimulate but my body’s<br />

having none of it. I drain my cup<br />

and return to the window, its<br />

grubby pane now flecked with<br />

snow.<br />

I’m starting to think that the<br />

world’s turned its back on me. The<br />

girl I picked up last night left before<br />

it was light and didn’t leave a<br />

number. Nobody else is answering<br />

my calls. No one’s calling either. I lie<br />

on my bed, put a CD on and spend<br />

the next six minutes listening to<br />

3<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

Bob Dylan attempting to cure<br />

America’s ills by calling forth the<br />

spirit of a long-dead blues singer.<br />

That fails to inspire me much either,<br />

so I turn off the player and lie in<br />

silence, counting down the seconds<br />

until I have to rouse myself and head<br />

off to work.<br />

I’m the assistant manager of a<br />

video shop. Correction: a back-alley<br />

video shop. Our closed sign’s<br />

scrawled on a piece of Weetabix box<br />

and our selection’s limited. Often I<br />

try to broaden our customers’<br />

horizons, suggesting they try<br />

something a little artier than the<br />

norm, but rarely are they having any<br />

of it. Tonight it’s particularly quiet.<br />

There’s a new multi-national store<br />

due to open up the road in a couple<br />

of weeks and I reckon most of our<br />

clientele are saving themselves for<br />

that. It’s a sobering thought. I really<br />

don’t see how we can stay in<br />

business after it hits.<br />

I decide to amuse myself by<br />

staring at the wall and asking<br />

rhetorical questions. Who am I?<br />

What am I doing here? Basic<br />

existential stuff. A couple of girls<br />

come in while I’m doing this and<br />

leave hurriedly, giggling. It doesn’t<br />

really bother me. I get paid the same<br />

whether they rent anything out or<br />

not. Later, about ten, just as I’m<br />

preparing to head home, the shop<br />

fills up and I find myself bombarded<br />

with videos from all angles. A Hugh<br />

Grant flick here, a Halle Berry<br />

there. One kid, obviously underage,<br />

tries to get out a Van Damme – one<br />

of his later straight-to-video jobbies.<br />

I ID him and he presents me with a<br />

laminated piece of cardboard that<br />

he’s obviously scanned off his<br />

computer ten minutes beforehand.<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008

When questioned about its legitimacy he just shrugs<br />

and asks what harm it can do.<br />

Before cashing up I check the inbox on my phone. It<br />

makes unpleasant reading: no new messages. I turn off<br />

the main lights and complete my chores by the flickering<br />

of the popcorn machine and the second-hand rays of the<br />

streetlights outside. 2ps, 5ps, 10ps, 20ps…I arrange<br />

them all in order, in rows, just how the boss likes them.<br />

The door flies open and a man comes barging in,<br />

collar pulled up high, his head masked by a balaclava. I<br />

draw his attention to the closed sign on the door but he<br />

doesn’t want to listen. He wants the money in the till,<br />

the money I’ve just spent the last<br />

twenty minutes arranging, the<br />

money that was providing me<br />

with an excuse not to head home.<br />

We struggle and the money goes<br />

flying everywhere. This angers<br />

me. I hate to see my handiwork<br />

undone, and I go for him, biting<br />

and scratching, trying to wrench<br />

the wool from his face. He’s far<br />

too strong for me though, and I<br />

find myself flung against the wall,<br />

a knife pressed up close to my<br />

throat.<br />

‘Make another sound,’ he hisses, ‘make another<br />

sound and I promise that I’ll fucking kill you!’<br />

‘Kill me?’ I chuckle. ‘I’m already dead.’<br />

3. The Silver-Tongued Devil<br />

***<br />

The beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad, so I had<br />

another for desert. Pellets of rain clattered into the<br />

windows, launched from the swirling wisps of cloud<br />

that circled above. The clock hit eleven with a<br />

begrudging ‘thunk.’ I gathered up my overcoat, slung it<br />

on and headed for the door.<br />

Outside a kid swore at a can that he was kicking; the<br />

tires of a U-Haul truck squealed; a man with a badge<br />

skipped on by; the smell of frying chicken aroused my<br />

nostrils. I passed it all by and blundered into the nearest<br />

bar, rubbing my malnourished eyes as the artificial<br />

lights hit them.<br />

She was stuck in a world<br />

where she didn’t belong; if<br />

she left him then she left<br />

everything. Gutsy little thing<br />

went ahead and did it.<br />

Credit to her.<br />

4<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

The barman nodded and handed me a beer. I<br />

thanked him and surveyed my surroundings, mapping<br />

out the day. Drank my beer down and gazed out the<br />

window. Traffic flashed past, a girl in an orange dress.<br />

The bar was filling up now; people were on their lunch,<br />

eating, drinking. Smoke hung low in the air and I had to<br />

rest my chin on the bar to escape it. Time passed and I<br />

went with it: some kids being refused admission, the<br />

whirring of a fruit machine, the monotony of the<br />

barman’s chatter. Life became a haze, a smoke-filled<br />

oblivion. My eyes strained against it, working harder<br />

than anticipated. There was a girl alone at a table –<br />

brunette, nice smile.<br />

I introduced myself. Talk<br />

flowed freely. I lied about my day;<br />

she did likewise. There was a<br />

copy of the local rag on the table<br />

and we skimmed through it.<br />

Seems there’s a killer on the loose.<br />

The press have dubbed him ‘The<br />

Silver-Tongued Devil’. He<br />

charms his way into people’s<br />

houses, wins their trust and then<br />

slays them. Uses whatever’s at<br />

hand. Sometime last month he<br />

caved an old lady’s skull in with a brick. It made one hell<br />

of a mess on the carpet. I pointed this out to the girl and<br />

warned her against being out late at night; she did<br />

likewise. We laughed, inhaled smoke, watched it follow<br />

its tail, round and round. She was alone for the night,<br />

had walked out on her bloke. The barman came over<br />

and brushed aside the glasses, winking at me. We<br />

continued talking, had lots in common. Poor little thing<br />

had got involved with the wrong guy and hadn’t realised<br />

until it was too late. It was a nasty situation: she was<br />

stuck in a world where she didn’t belong; if she left him<br />

then she left everything. Gutsy little thing went ahead<br />

and did it. Credit to her.<br />

The drinks kept flowing and our jaws kept jacking,<br />

hours melting into hours as we exchanged stories about<br />

a world gone wrong. Then the bell rung, last orders<br />

were called and we were out in the street, arm in arm,<br />

heading for her place. The rain still came but it was<br />

almost apologetic now, its rage quelled. We bantered<br />

on the doorstep, standing in defiance of the cold. The<br />

door was opened and we staggered inside. Laughter,<br />

jostling, the smell of wet denim.<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

World Gone Wrong<br />

Ben Hart

Glasses were cleaned, filled and<br />

clinked. Lips touched lips. We<br />

joked about the Silver-Tongued<br />

Devil, wondering what he’d do if he<br />

caught us now. She wanted to fuck<br />

him and fuck the world. Lips again,<br />

chapped, balmed. Then the carpet,<br />

the burning, the pleasure, the<br />

screaming. I left her there, smiling,<br />

as happy and beautiful as anything<br />

I’d ever known. She was rigid,<br />

sleepy. I headed for home.<br />

The night was souring. Water<br />

sloshed around my ankles, seeping<br />

into my socks. A crack of a twig, the<br />

dirty stench of dying. The Silver-<br />

Tongued Devil was there, walking<br />

behind me. I fell, hands clammy, my<br />

throat choked with dust. Footsteps<br />

moving away, slowly, then quicker.<br />

I lay there, watching the rain flow<br />

into the gutter, wondering why he<br />

did what he did. Then the answer<br />

dawned: immortality. The death of<br />

the weak made him a God. You, me,<br />

them, she – we only live until we die.<br />

He will live forever. And to be<br />

remembered…is that not all any of<br />

us can ask for?<br />

The next morning I gargled, spat<br />

and headed down to the bar to face<br />

the day. The barman handed me a<br />

beer, told me the police had been in<br />

earlier, asking about the girl. I<br />

picked up the rag and browsed. He<br />

was in it again, that Silver-Tongued<br />

Devil. The opening of a new coffee<br />

shop had consigned him to page<br />

two. It was a paid advertisement.<br />

Pathetic. Absolutely pathetic.<br />

I tried to reason, to understand. I<br />

knew why but not how. Couldn’t<br />

comprehend how anyone could do<br />

what he did, without remorse.<br />

Except he did feel remorse, didn’t<br />

he? The days after the nights before<br />

the nights were spent in bars,<br />

slumping into depression, trying to<br />

find a reason not to go home.<br />

Eventually he’d probably find so<br />

many that he wouldn’t go back at all.<br />

He’d just sit there, always, searching<br />

for the adulation of the press.<br />

The smoke was hanging around<br />

again. My eyes saw page two. Page<br />

two. He killed and only made page<br />

two. Sad, like a child deprived of a<br />

bike, like a mother seeing her boy off<br />

to war, like a man who can’t see the<br />

road for tears in his eyes. Smoke.<br />

Everywhere. Take it back, passive,<br />

causes cancer, fuck it, we all die<br />

anyway. He’ll see to that. Nothing<br />

annoys the Silver-Tongued Devil<br />

more than being deprived of his<br />

rightful place on the front page by<br />

the opening of a new coffee shop. I<br />

was there when it happened and I<br />

doubt I will ever forget his rage:<br />

tables were overturned; cups and<br />

curses flew in unison.<br />

Pantoum – The Prophet<br />

The End Is Nigh!<br />

The Prophet yells,<br />

Words echoed in the sky.<br />

You have been told,<br />

The Prophet yells,<br />

The blasphemy of it all,<br />

You have been told,<br />

Heed Gods call!<br />

The blasphemy of it all,<br />

Reaching to the air.<br />

Heed Gods call!<br />

He yells a dare.<br />

Reaching to the air,<br />

His arms wave aimlessly.<br />

He yells a dare<br />

To those that can see.<br />

5<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

The smoke was a shield, it broke.<br />

His anger continued unabated<br />

throughout the night. He swore<br />

he’d kill again. I felt him slip from<br />

the shadows, the smoke coming<br />

down like a curtain across the latest<br />

act. The girl was gone; the police<br />

were coming; it was time for him to<br />

leave.<br />

Rubbing my eyes, blinking,<br />

disbelieving, I watched as The<br />

Silver-Tongued Devil ran. I went<br />

with him, alongside him, keeping<br />

pace. Our eyes locked, trust was<br />

established. The clouds soared, the<br />

rain danced, the sun was tentative,<br />

the horizon near.<br />

Ever since that day we’ve been<br />

brothers, the Silver-Tongued Devil<br />

and I, though some say we’re one<br />

and the same.<br />

***<br />

undergraduate poetry<br />

His arms wave aimlessly,<br />

Grasping the ideas.<br />

To those that can see<br />

They spark many fears.<br />

Grasping the ideas<br />

He thrusts them below.<br />

They spark many fears<br />

An unholy blow.<br />

He thrusts them below,<br />

Words echoed in the sky,<br />

An unholy blow.<br />

The End Is nigh!<br />

Marc Spencer<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

World Gone Wrong<br />

Ben Hart

4. Hard Times<br />

Ihad spent many lonely, restless nights dreaming of<br />

how I was going to greet my family when I was<br />

released from prison. On the day, I settled for a<br />

rudimentary hug from my mother and sister, and a slap<br />

on the back from my old man. They hurried me out of<br />

the prison gates and bundled me into the car. My mum<br />

muttered something about a party and how the guests<br />

would already be arriving. I smiled, seconds and even<br />

minutes flashing past as a blur. My sister hugged me<br />

again and told me how much she’d missed me. I forced<br />

another smile. As we drew ever nearer to home the<br />

conversation became stilted: I had little to tell them and<br />

they had told me all in their letters. Slumping back in<br />

my seat, I stared out the window and watched the birds<br />

soar out majestically above the<br />

hills, searching for food, secure in<br />

their purpose.<br />

We pulled onto our driveway<br />

some thirty seconds later. The car<br />

door was flung open and I was<br />

coated in relatives. Some regulars,<br />

others long lost. They grabbed<br />

and prodded me, commented on<br />

my weight loss, my muscle gain, my aged features. It<br />

was as though I, their former golden boy, was a rough<br />

diamond they were determined to polish up until I<br />

regained my former glory. Tea was served soon after,<br />

brought out promptly on the hour. As the wine flowed<br />

more freely so did the chatter. I dipped in and out of the<br />

conversation, riding it like a wave, jumping off<br />

whenever things got too much for me.<br />

At around ten-thirty my mother decided I must be<br />

tired and ushered me up to bed. It had been made up<br />

specially – duvets and pillows both uniform blue.<br />

Thanking her, I cast aside my clothes and flopped down<br />

on the bed, shuffling uncomfortably as the mattress<br />

sunk down and threatened to engulf me. My mother<br />

collected up my clothes and placed them in the washing<br />

basket.<br />

‘Breakfast will be at seven,’ she whispered, bending<br />

down to kiss me on the forehead.<br />

I murmured my acknowledgement and did my best<br />

to sleep.<br />

It was a rough night. Free from the catcalls of my<br />

fellow cons and my cellmate’s snoring, I was left at the<br />

I spent the rest of the day<br />

being paraded around like a<br />

trophy. By the end I had just<br />

about perfected a false grin.<br />

6<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

mercy of my own dreams. Time and time again they<br />

came and, try as I might, I was powerless to stop them.<br />

Snippets of conversations, half-formed figures,<br />

encounters long since forgotten. I saw my life before I<br />

was sent down, I saw prison, and I saw my future. None<br />

of it seemed all that different to me.<br />

The next morning I slouched downstairs dead on<br />

seven and was greeted by the glorious smell of wellgrilled<br />

bacon. After bidding good-morning to all, I<br />

pulled up a chair and sat down alongside my sister. She<br />

smiled sweetly and offered to do something about my<br />

hair. The bacon was placed in the centre of the table and<br />

we all made a grab for it, laying slices out on slabs of<br />

thickly buttered bread. The taste was unparalleled but<br />

caused me to feel oddly nauseous. My stomach<br />

churning, I left the table and<br />

charged upstairs to the bathroom<br />

to be sick.<br />

I spent the rest of the day being<br />

paraded around like a trophy. By<br />

the end of it I had just about<br />

perfected a false grin. After being<br />

marched around the shops and<br />

kitted out in the threads my<br />

mother and sister agreed that I ought to be wearing,<br />

and enduring a dinner of lamb and sweet potatoes, I<br />

finally managed to slip away. Breathing deeply and<br />

savouring every breath, I reached the edge of the street<br />

and surveyed my surroundings, marvelling at how little<br />

had changed in the three years I had been away. The<br />

same people still scuttled around in the same houses,<br />

doing the same things. I paused to admire the stars that<br />

winked out in the night sky, stately yet ominous, the real<br />

masters of the universe.<br />

I pushed open the door to the ‘Jolly Bargeman’ and<br />

stepped inside. The musty air hit me and I longed to<br />

wipe it from my face. Over in the far corner sat my old<br />

crew, drinking, smoking, playing cards, pretending not<br />

to gamble. They hollered me a greeting and I raised my<br />

hand in acknowledgement. The barman had already<br />

poured me a pint when I got there. Someone must have<br />

briefed him about my arrival. I paid for the drink,<br />

fumbling my coins slightly, and took a seat alongside my<br />

friends.<br />

‘Great to have you back!’ One of them yelled<br />

‘We’re up for a biggun tonight!’ yelled another.<br />

‘Pub crawl next week? It’s Johnny’s birthday!’<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

World Gone Wrong<br />

Ben Hart

‘Gotta be done!’<br />

‘Got to!’<br />

‘Got to!’<br />

‘Got to!’<br />

I wanted to stand up and scream,<br />

tell them to shut up, to shove their<br />

stupid ideas and mind their own<br />

fucking business. Their voices were<br />

relentless, piercing, incessant. I<br />

leaned back in my seat and closed<br />

my eyes, dreaming that I was far<br />

away, in another land, another time.<br />

‘So,’ someone asked. ‘How does<br />

it feel to be free?’<br />

I opened my eyes and stared<br />

across the table, looking them all in<br />

the eyes individually. Finally I<br />

spoke.<br />

‘Go find me a man who knows.’<br />

***<br />

5. Good as I’ve Been to You<br />

Old Dougie was a local treasure.<br />

He spent his days returning<br />

stray shopping trolleys to their<br />

rightful owners. To him they were<br />

lost sheep that were pining for their<br />

flock. He received no monetary<br />

reward for his actions, or thanks,<br />

but it gave him a purpose, a reason<br />

to exist, something to occupy his<br />

time with as he approached his<br />

eightieth year on the planet.<br />

At night he’d huddle on a park<br />

bench, sleeping bolt upright, knees<br />

pulled up close under his chin, his<br />

face crouched down below a flatcap.<br />

If the weather was bitter then<br />

he’d pull up the collar of his grubby<br />

mac to muffle its advances. The<br />

bench he most often frequented was<br />

situated near the town’s Catholic<br />

Church, directly adjacent to its<br />

huge iron gates that rose up high<br />

into the sky. Above these gates,<br />

mounted on a concrete plinth, were<br />

three concrete angels playing<br />

trumpets.<br />

One night, as he was admiring<br />

the angel’s architecture, a downand-out<br />

took a seat alongside him<br />

and began to swig noisily from a<br />

bottle of cheap cider.<br />

‘Lo,’ said Dougie, regarding the<br />

man with interest.<br />

The man grunted nasally and<br />

held out the cider. ‘Want some?’<br />

Dougie shook his head. ‘Don’t<br />

touch the stuff.’<br />

The two men stared up at the<br />

angels, their ragged features bathed<br />

in ethereal streaks of moonlight.<br />

7<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

‘How long you been out here<br />

for?’ asked the man.<br />

‘About two years. My son was<br />

manoeuvring to put me into a home.<br />

I ran.’<br />

The man turned towards<br />

Dougie, his mouth quivering and<br />

threatening to gape out from behind<br />

his greying beard.<br />

‘You’re out here on your own<br />

will?’<br />

Dougie nodded.<br />

There was a service in the<br />

church, always was on Thursday<br />

nights. As the clock struck eight,<br />

ringing out mightily through the<br />

caustic night air, people started to<br />

file out of the building: kids,<br />

parents, grandparents. They were<br />

laughing, joking, singing snatches<br />

of hymns. They passed Dougie and<br />

the old man by, barely affording<br />

them a glance.<br />

‘Do you think anyone hears the<br />

music that they play?’ asked Dougie,<br />

suddenly, gazing up at the angels<br />

that stood high above him with<br />

their trumpets clasped tight.<br />

‘Do you reckon anyone even<br />

tries?’<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

World Gone Wrong<br />

Ben Hart

Parting Gift<br />

by Carolyn Skelton<br />

He opened the door to her, not<br />

even bothering to hide his<br />

irritation. Hadn’t he told her only<br />

last month that it was all over? All<br />

over before it had really started,<br />

she’d said, ripping her paper<br />

handkerchief into shreds. For days<br />

after he’d found tiny bits of mangled<br />

tissue paper behind the furniture in<br />

the living room. Like a paper trail<br />

from the heart which led nowhere.<br />

‘Ray! How’s things?’ she asked, a<br />

smile stretched taut across her face.<br />

She hitched her tote bag higher up<br />

on her shoulder. It was then he<br />

noticed the leather gloves. They<br />

looked incongruous with her light<br />

sweater and jeans. He ignored the<br />

thought that she might be covering<br />

up some sort of self-mutilation. In<br />

any case, it would be more like her<br />

to flaunt the results of a half-baked<br />

suicide attempt, knowing it would<br />

press all his guilt buttons.<br />

‘Hey, Carrie.’<br />

‘I was just passing and . . .’ she<br />

continued.<br />

‘I’m packing.’<br />

‘For Pakistan?’<br />

‘Uh-huh. I’ve loads to do. The<br />

flight leaves tonight.’<br />

‘I’m not stopping. Just wanted to<br />

give you this.’ She bent her head<br />

over her bag, auburn curls flashing<br />

in the sunlight. He remembered the<br />

softness of her hair as it brushed<br />

against his thighs, and shook his<br />

head to dislodge the memory. It<br />

wouldn’t do to get too sentimental.<br />

Not now.<br />

She pulled out a small gold box<br />

and handed it to him. ‘Don’t open it<br />

yet. Keep it for the twentieth.’<br />

‘I’m not sure . . .’<br />

‘See it as a parting gift. A way of<br />

saying “thanks”.’<br />

‘For what?’<br />

‘Helping me to realise that you<br />

and I would never have made it.’<br />

‘Oh.’ He felt deflated now. ‘Do<br />

you want to come in or something?’<br />

‘Another time maybe.’<br />

Pure Research<br />

8<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

‘Perhaps. I’ll be away for a month<br />

at least.’<br />

‘Just promise me you’ll keep it for<br />

the twentieth. You might need it out<br />

there in all that heat.’<br />

Outside, ominous cobwebs of tree, branches waving at the window pane,<br />

A sea of freeze-dried paralyzed limbs inside.<br />

I hear words like dripping blood and a thunder in my right ear:<br />

Warm, delicate, sinewy, scaly, oozing with the viscosity of mud,<br />

Murderous, fleeting, shady.<br />

Here talks a scientist in the bud, blossoms of grey crystalline cells,<br />

Alongside chrysanthemum and blue bells.<br />

This Bourne building is a prison for my carcass, bound in flowers,<br />

a garrison for plaster and tape people, the waste bubbling up,<br />

when Enrique, with great haste, belches words<br />

about dominant negative mutants.<br />

Unfortunate, to be all crammed in this office, like ants:<br />

Robert is indifferent, honest;<br />

Claudia, with laser beams and paper moons, idly staring at the ceiling;<br />

Christine reaches with intensity, dedication, reaches for science’s secret;<br />

Prajwal perches on the sofa, stifling a yawn;<br />

Enrique, flamboyant and patronizing, throws jargon at people;<br />

And all the while I smile arrogantly at the trees outside.<br />

Paul, diligent, calm,<br />

argues his point with care,<br />

while Wang, vampire-like,<br />

stands in awe of his master.<br />

Virginia sits<br />

in front of them,<br />

indulgent<br />

and benign,<br />

betraying a sense of superiority.<br />

undergraduate poetry<br />

Michael, being English,<br />

fumbles with<br />

hands and floppy hair,<br />

while Laci,<br />

smiling like a Japanese fox,<br />

curls in his seat,<br />

ready to fire yet another question.<br />

Emanuele Libertini<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008

He looked down at the box in his hands as if he’d<br />

only just noticed it. ‘Sure. I’ll send you a postcard.’<br />

‘Great.’ She bent forward as if to give him a kiss and<br />

he instinctively moved his head away. Her lips landed<br />

on his ear and he pulled back. She turned away quickly<br />

and headed up the path, only pausing at the gate to take<br />

off her gloves and stuff them into her bag. He watched<br />

her go and felt nothing but relief.<br />

Several times that afternoon he was tempted to open<br />

the box. His thirty-eighth meant nothing to him:<br />

birthdays never had been celebrated much in his family.<br />

But he remembered that look on her face when he’d<br />

dodged her kiss. It had reminded him of his mother’s<br />

that time he’d told her he wanted to live with his father.<br />

All hurt and defiance. An expression designed to make<br />

you feel bad.<br />

In the end he just threw her present into the suitcase.<br />

He was running late as usual and he’d planned to do<br />

some duty free shopping before his flight. Of course the<br />

ubiquitous malt was out, but the research team always<br />

appreciated a tin of shortbread or a mouse mat of the<br />

Cuillins. Something they couldn’t get in Karachi.<br />

The airport was crowded with families. He’d<br />

forgotten it was spring half term. That was the thing<br />

about not having children: you had no idea of the school<br />

calendar and were always surprised when they suddenly<br />

appeared everywhere. The queues for Malaga and<br />

Tenerife snaked out across the concourse. He dodged<br />

the track-suited families with their bulging bags, smug<br />

in the knowledge that he was travelling light. His small<br />

suitcase on wheels jerked and whined behind him like a<br />

recalcitrant dog as he headed over to the Pakistani Air<br />

desk.<br />

‘Window or aisle?’ asked the check-in clerk, giving<br />

him one of her professional smiles.<br />

9<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

‘Window.’ He wouldn’t see anything at night, but he<br />

hated being disturbed when others wanted to get out<br />

of their seats. He hoped the flight would be smooth –<br />

not like the last time when they’d run into turbulence<br />

somewhere over the Middle East.<br />

A couple of security guards, machine guns strapped<br />

to their chests, glanced at him. Travelling nowadays<br />

was like being in a war zone. Particularly when flying to<br />

what were now casually referred to as ‘volatile regions.’<br />

He picked up his passport and boarding card and<br />

headed towards departures. No doubt there would be<br />

the usual nonsense of queuing for ages only to<br />

eventually be manhandled by some bored guy with an<br />

electronic baton. Thank God he only made the trip once<br />

a year. He pitied those exhausted looking executives<br />

who seem to spend their lives shuttling from one time<br />

zone to another, permanently bloated from airline food<br />

and cheap whisky.<br />

‘Dr Noble?’<br />

He turned to see one of the security guards at his<br />

elbow.<br />

‘Yes?’<br />

‘Would you come this way, please.’<br />

‘Of course.’ Stay calm. Stay calm and polite. ‘Is there<br />

anything wrong?’<br />

‘Please just follow me.’<br />

He allowed himself to be steered into a small<br />

windowless room. A bench ran along one wall. In the<br />

middle was a table where his suitcase lay gaping open<br />

like a wound, its disembowelled contents spilling out.<br />

His breathing came faster. Something wasn’t quite<br />

right with this scenario. He was Raymond Noble PhD,<br />

heading off to work on the diseased phytoplankton in<br />

the Bay of Karachi. He was the Pakistani research<br />

station’s great white hope, bringing new observation<br />

techniques to the underfunded fisheries lab.<br />

‘What’s going on here? What are you doing<br />

with my case?’<br />

A pair of handcuffs slid around his wrists.<br />

The cold metal made him wince. His bowels<br />

slackened.<br />

It was then he saw it. The little gold box,<br />

slashed and broken. The red silk cravat<br />

poking out of the tissue paper like a malicious<br />

tongue. But beside that something far worse.<br />

The false bottom smashed and ripped to<br />

reveal a dark, oblong object wrapped in<br />

cellophane. Something which looked like an<br />

overlarge laboratory faecal specimen.<br />

Carrie’s parting gift.<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Parting Gift<br />

Carolyn Skelton

Hodge<br />

by Jo Hurst<br />

During the daylight hours I am<br />

a respectful returner. I don’t<br />

rampage as the menagerie up at<br />

Newstead Abbey do. I am quiet and<br />

creep around the rooms that I once<br />

had full run of.<br />

That we only appear at night is<br />

untrue. That we choose to appear<br />

more frequently after darkness,<br />

when we are alone, when our home<br />

returns to us, is more the truth;<br />

though coming back often fills me<br />

with melancholy.<br />

It saddens me to think that our<br />

house has become an institution.<br />

It used to live and breathe with<br />

us, around us, through us. Now it<br />

is a just a space, orchestrated to<br />

offer visitors authenticity of times<br />

passed.<br />

To this end, the interloping<br />

custodians have employed a cat;<br />

to maximise the potency of the<br />

recreation. To recreate me, no less.<br />

To meander and muse her way<br />

around the parlour furniture, while<br />

strangers exhume memories of and<br />

pontificate on, my Master and His<br />

world. My Master and His Work.<br />

That they have chosen a feminine<br />

feline confuses; though I feel it is<br />

because they believe everything they<br />

hear or read on us. Therefore let me<br />

put straight, any distortions<br />

immediately. When the Master,<br />

while I entwined myself around his<br />

leg, said to his very excellent friend,<br />

Boswell, those many years ago now,<br />

‘I have had better cats,’ you believed<br />

that he loved me less? That I wasn’t<br />

the favourite? That those who<br />

graced his presence be they male or<br />

female, before or after me were held<br />

in higher esteem?<br />

To those who say such things,<br />

utter such mutterings, I say this.<br />

Whose bronze statue adorns the<br />

entrance here? Who was there<br />

when the real writing was done?<br />

When history was made. Whose<br />

name do they remember now?<br />

Together, my Master and I made<br />

something out of not much indeed<br />

and there wasn’t a multitude of us<br />

like there was in France. There was<br />

just the Master and His quill, and I.<br />

Hearsay can become heresy if<br />

attention is not paid. So take heed.<br />

Take all that you hear or read with a<br />

pinch of salt and a dollop of vinegar,<br />

the way I used to take my fish down<br />

at the Wharf. Pay attention to the<br />

unreliability of scribes historical and<br />

‘He is a very fine cat,’ my<br />

Master said.<br />

And He was a very sensible<br />

Man.<br />

certain memorists with perforated<br />

remembrances.<br />

And as you weren’t there I shall<br />

repeat the actual words spoken of<br />

me.<br />

‘He is a very fine cat,’ my Master<br />

said.<br />

And He was a very sensible<br />

Man.<br />

As was Poet Stockdale who<br />

wrote on me in his Elegy on the<br />

Death of Dr Johnson’s Favourite<br />

Cat. So what further proof do you<br />

need of my beloved status?<br />

Of course two such intelligences<br />

living under the same thatch can<br />

often bait each other’s<br />

imperturbability. And that my<br />

Master some time later broke a little<br />

piece of my small beating leonine<br />

heart when I uncovered my entry in<br />

the Dictionary, I have put behind<br />

me. And I lay it bare, the exact<br />

words here for all to see, to show my<br />

10<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

spirit has left all base worldly upsets<br />

in the physical sphere.<br />

‘A domestick animal that catches<br />

mice, commonly reckoned by<br />

naturalists the lowest order of the<br />

leonine species.’<br />

For I can assure you I was my<br />

Master’s cat and I did much more<br />

than catch mice.<br />

For our achievements were<br />

mountainous; that the strangers<br />

whom I see here and chose to like<br />

not, have made mere curiosities of<br />

us, goads me. They do disservice<br />

our memories. Though I am not<br />

allowed to voice my disapproval. I<br />

am reminded that my memory is<br />

short and in the days before we’d<br />

gone to the Gods, we welcomed<br />

waifs and strays, strangers all.<br />

And this is true enough.<br />

‘Hodge,’ He says, to remind,<br />

‘We kept our door ajar so that they<br />

could share tea and brandy with<br />

me and milk and oysters with you.<br />

So that they could find welcome at<br />

whatever hour.’<br />

I hadn’t forgotten. I am my<br />

Master’s cat. But a stranger once<br />

talked to is a stranger no more.<br />

What do I have in common with<br />

these people who haunt our home<br />

now? They are not the loose<br />

moggies and prostitutes, the<br />

vagabonds and wayward tabbies<br />

and ally cat beggars that frequented<br />

our home in those days, who were<br />

all welcome. Not just welcomed,<br />

needed. We did indeed keep our<br />

door ajar for the misfortunates,<br />

because we ourselves were<br />

misfortunates. They kept us sane<br />

and although we enjoyed the<br />

company of respected human and<br />

feline folk, the melancholia we<br />

shared, my Master and I, sat well<br />

with them.<br />

These unfortunates suffered too<br />

our illnesses, tics and complaints<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008

that visited upon us. For they like us<br />

were afflicted. We, like them, from<br />

base beginnings. And being from<br />

such base beginnings we were<br />

forever humbled, and knew what it<br />

was like to forgo experience and<br />

knowledge. To forgo such natural<br />

entitlements because we did not<br />

have the money to pay for such<br />

things. That my Master devoured<br />

books, borrowed before he could<br />

buy, was the measure of the Man’s<br />

Majesty. Myself, the same. I too was<br />

known for my intelligence and could<br />

discourse on topics of the day at my<br />

Club as my Master did at His;<br />

when the melancholia left us alone.<br />

Oh, history teacher, my history teacher<br />

His shirt, trousers and socks were beige,<br />

But he was not.<br />

He was a history teacher.<br />

A damn fine history teacher.<br />

The King of all Kings of historical matter.<br />

What he didn’t know about the Tolpuddle Martyrs or<br />

the French Revolution<br />

Could be written on the back<br />

Of his unstarched, dirty shirt collar<br />

Coloured walnut brown,<br />

The same as his squashy shoes and buckled belt.<br />

He arrived for class as unmade<br />

As the bed he’d got out of,<br />

His hair worn long and thin<br />

Greased stagnant as he breezed in.<br />

He had what all great teachers should have: Presence.<br />

And this Presence was Flagrant. Felt. Electric.<br />

So electric that if your elbow happened to overhang<br />

the aisle<br />

He bestrode like a colossus,<br />

You’d feel the wrath of his nylon trousers<br />

And be zapped into participation<br />

By the static he’d built up in them<br />

Through his continual pacing.<br />

He talked non-stop with nasal-voiced authority<br />

Constantly swirling round to engage everyone.<br />

His bodily fluids set free.<br />

Spittle cascading out of his mouth<br />

Like the spray off a water-logged dog drying off.<br />

But accompanying the spittle and the sweat<br />

For at times it did blanket and<br />

overwhelm us.<br />

The year the Master’s beloved<br />

died, lost to age and unclean living,<br />

in particular left us heavy of heart<br />

and alone to witness the unveil of<br />

His life’s work. At times the<br />

despondency was like a fog, so thick<br />

that one had to step on to the streets<br />

for air and vision; to seek life. I<br />

forever marvelled at what I saw.<br />

Though I had seen it a thousand<br />

times, I never grew tired of it. For to<br />

grow tired of London is to grow<br />

tired of life. And it kept us both from<br />

succumbing for eternity to our<br />

depressions.<br />

11<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

My Master would go and see his<br />

eminent friends for solace and I<br />

would go to the Wharf and watch<br />

the nature unfold. Freed from the<br />

confines of a house dominated by<br />

sickness; we could contemplate,<br />

ruminate, think on the reception my<br />

Master was receiving and the praise<br />

I had heaped on me for my dutiful<br />

companionship. And when we<br />

returned from the streets and to the<br />

Square, the melancholia lifted, we<br />

would thank the good Lord that we<br />

had found contentment and<br />

consolation. My sensible Master<br />

and His Favourite and Fine Cat,<br />

Hodge.<br />

History poured out of his apertures.<br />

History, and nothing but.<br />

For those forty-five minutes, you were with him.<br />

Bearing banner on the battlefield at Hastings<br />

Holed up in the Tower,<br />

Exchanging notes through nooks.<br />

By his side with bayonet pointing east at Flanders.<br />

Marching on Washington,<br />

Arms and thoughts linked with belief<br />

In what should be.<br />

So what that he looked liked a bonfire Guy Fawkes<br />

And smelt like a spare room between guests?<br />

So what he bypassed the shower?<br />

He was a busy, learned man<br />

With things to teach and students to be taught.<br />

Washing was a luxury for other people.<br />

And thankful we were for this diligence.<br />

Thankful for those 45 minutes<br />

When we were made to feel like he felt about history.<br />

When we became a Roman centurion<br />

A scared stiff Tommy<br />

A White Russian for a day.<br />

Looking back, I wager there’s not one person<br />

From that classroom,<br />

Having lived half a life by now,<br />

Who wouldn’t give up their loofah and soap<br />

To feel that passionately about something.<br />

Not one.<br />

Jo Hurst<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Hodge<br />

Jo Hurst

Magilligan<br />

by Johanna Yacoub<br />

Employment<br />

Henri Magilligan, a short<br />

stocky man, seemed to stand<br />

at a lop-sided angle to his<br />

surroundings. One shoulder sat<br />

lower than the other. One leg was<br />

shorter than the other. His left arm<br />

hung farther down his body than his<br />

right arm. This right arm, visibly<br />

smaller, tucked itself into the<br />

waistband of voluminous but<br />

threadbare jodhpurs bunched up by<br />

frayed baling twine slotted through<br />

their waistband. He counteracted<br />

the discrepancy in his legs by<br />

keeping the longer of the two limbs<br />

slightly bent and positioned a foot’s<br />

length to the front. His head,<br />

topped by a burning bush of ginger<br />

hair, was graced with an off-centre<br />

crescent smile which wrapped itself<br />

around his face. He appeared to<br />

have all his teeth.<br />

It was six thirty in the morning.<br />

The grate had been cleaned and the<br />

fire made up, but not yet relit. The<br />

room was cold. A gunmetal sky<br />

threw its dark cloak over the<br />

chateau and the gusting wind<br />

clattered the shutters against the<br />

wall on either side of the long<br />

windows. Jeanne had lit the oil<br />

lamps. Generator fuel was in short<br />

supply and electricity was only<br />

switched on for visitors.<br />

André twisted an old regimental<br />

scarf into a makeshift turban to<br />

protect his sensitive skin from the<br />

ferocious draught howling along<br />

the corridor. He’d wound his body<br />

in a Berber camel hair burnoose, a<br />

souvenir of colonial life. Examining<br />

himself in the mirror, he recollected<br />

the day he’d met Alexia, the spirited<br />

cavalry charge and the mock<br />

capture of Abdel Kadir. ‘Poor Abdel<br />

Kadir,’ he thought. ‘Even you<br />

looked better than I do now. Who’d<br />

have thought I’d end up like the<br />

monster in Frankenstein.’ Then he<br />

wheeled himself unaided from the<br />

bedroom, allowing Alexia to return<br />

to her room and change. As she<br />

scuttled past Henri, she paused,<br />

gawped, looked with incredulity at<br />

Jeanne and fled.<br />

They’d had a difficult night.<br />

André had grown accustomed to<br />

the hospital beds and found the soft<br />

mattress unsettling. His wounds<br />

were tender and every accidental<br />

movement in the bed painful. He’d<br />

woken frequently, each time<br />

disturbing Alexia. The enormity of<br />

their problem had sunk into her<br />

head. She was ready to grab any<br />

straw within reach with both hands.<br />

‘The name Magilligan,’ began<br />

André in his quiet voice, ‘it’s not<br />

exactly French....? Are you...were<br />

you a member of the armed forces?’<br />

Henri wrinkled his face in<br />

concentration, glanced briefly at<br />

Jeanne, then replied,<br />

‘Do I look like a soldier? I’ve<br />

great skill with horses and I did<br />

offer myself but neither your lot nor<br />

my lot were interested. They’ve<br />

already got enough horse copers<br />

and no-one detected the fighting<br />

potential in me. So, the answer is<br />

no, I was not in the armed forces.’<br />

André hesitated, as if<br />

reconsidering his tactics. He started<br />

again.<br />

‘I’m trying to find out if you’re a<br />

deserter.’<br />

‘I was never in the army to run<br />

away, Sir.’<br />

‘Magilligan, if that is your name?’<br />

André, confused, stopped. He<br />

wasn’t sure what he was trying to<br />

ask this odd-looking little man. ‘It’s<br />

not a French name yet you speak<br />

12<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

French like a Frenchman. What if<br />

you’re a spy?’<br />

He regretted the question as<br />

soon as he’d asked it. ‘He’ll think I’m<br />

paranoid,’ muttered André to<br />

himself, but Magilligan seemed<br />

unperturbed by the insinuation.<br />

‘My grandfather was the<br />

Magilligan. Irish, but I never knew<br />

him. Drank himself to death before<br />

I was born.’<br />

Magilligan looked at André and<br />

raised his bushy eyebrows as if to<br />

deny any involvement in the<br />

inebriated downfall of his forefather,<br />

then let them subside to their<br />

natural resting place above his vivid<br />

blue eyes. André threw a fleeting<br />

look of bewilderment at Jeanne,<br />

whose face remained expressionless.<br />

‘My grandfather and father<br />

worked with the racehorses at<br />

Chantilly. I can ride as well as<br />

anyone but the gaffers wouldn’t let<br />

me race, so I stayed a stable lad.<br />

Chantilly’s closed now, as you<br />

know. My mother, God rest her<br />

soul, had relatives near Chalons. I<br />

found farm work, Sir.’<br />

Remembering the main thrust of<br />

André’s investigation, he added as<br />

reassurance,<br />

‘Nobody would take me into the<br />

espionage. I stick too much to<br />

peoples’ memories.’<br />

‘Do you know this man well,<br />

Jeanne?’<br />

André manoeuvred the chair to<br />

face her. She nodded and was about<br />

to speak when André swung round<br />

again to Henri.<br />

‘I’m looking for a valet; a very<br />

personal valet. I need a man to help<br />

me with the basic functions of<br />

living.’<br />

André removed his hands from<br />

under the blanket and held them<br />

forward, as if for inspection. The<br />

fingers on his left hand were fused<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008

together though his thumb was free. He turned his gaze<br />

to Henri and asked,<br />

‘What in your previous experience qualifies you for<br />

this work?’<br />

André’s tone was sceptical. Jeanne closed her eyes in<br />

resignation. The net would have to be cast wider.<br />

Henri, however, replied with pride in his voice.<br />

‘I’ve soothed nervous foals and mares. I’ve gentled<br />

yearling colts to the bridle, without being bitten. You<br />

need a soft touch for that, and the ability to predict their<br />

next move. I’ve kept their rugs clean and saddles<br />

polished to perfection. What’s the difference between a<br />

harness and a pair of shoes?’<br />

André nodded and was about to answer, but Henri<br />

hadn’t finished his self-justification.<br />

‘I’ve laundered silks for Rothschild’s jockeys and<br />

ironed shirts for the trainers. The shaving might take a<br />

bit of practice but I’ve a steady hand and to be truthful,<br />

Sir, I don’t see much to shave.’<br />

Remnants of André’s beard straggled in isolated<br />

tufts around the areas of less burned skin. A few strokes<br />

of the razor would take it off in the blink of an eye. To<br />

overcome that uncomfortable truth, André focused his<br />

eyes on Henri’s right hand. It left the waistband in a<br />

flash, described a couple of circles in the air, waggled<br />

its fingers, then returned to its resting place once it had<br />

demonstrated its viability. No-one spoke.<br />

‘You see,’ said Henri interrupting the silence, ‘It’s<br />

much shorter than the other and<br />

bothers folk to look at it but I<br />

promise, it works as well as its<br />

partner. I’ve learned to drive a car,<br />

even had lessons in its machinery<br />

and I’m a good shot. I can reload a<br />

gun blindfolded. You want me to<br />

show you?<br />

‘Not at this precise moment,<br />

thank you.’<br />

André was at a loss. Henri was<br />

not what he’d had in mind for a<br />

manservant. He adopted a different<br />

approach.<br />

‘May I ask a personal question?’<br />

‘By all means, Sir. Ask whatever<br />

you want,’ replied Henri with an<br />

unconcerned shrug.<br />

‘Your, er, disability?’ André did<br />

not wish to be impolite or indelicate.<br />

‘Was it as a result of a riding<br />

accident?’<br />

Decadence in the Bathroom<br />

Porcelain-white tiles shine with gold,<br />

Soft candle flames bounce about the<br />

room,<br />

Unworldly.<br />

The drip-drop of water hits the floor,<br />

Bath overwhelmed, candles, dancing<br />

flames sent overboard,<br />

Waxy scent of vanilla is overcome by<br />

the stink of burning.<br />

And it started with such a tiny light,<br />

Dancing in the water,<br />

Playing with its reflection –<br />

A metamorphosis.<br />

Burning, out of control.<br />

13<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

‘No, Sir. God sent me like this into the world. He<br />

wanted to keep me safe from harm.’<br />

‘I don’t quite follow?’<br />

Henri’s logic escaped André. Jeanne, who’d known<br />

Henri’s maternal family since childhood, wondered<br />

what was coming. She couldn’t follow his logic either.<br />

‘Well, Sir,’ Henri adjusted his stance as his shorter<br />

leg was getting tired. ‘I’ve prepared horses for the<br />

military. All the officers to begin with are like you used<br />

to be, and often end up like you are now; that’s if they’re<br />

there at all. My bodily misfortune has kept me out of the<br />

fighting. At the end of it I’ll be what I was at the<br />

beginning, not better, that’s for sure, but no worse.’<br />

André closed his eyes. It was too early in the morning<br />

for this. He needed breakfast to unravel Magilligan’s<br />

clarification of God’s benevolence. Turning to Jeanne,<br />

he asked,<br />

‘Are you sure this man is up to the job? He looks as<br />

if he slept in the stables last night.’<br />

Before Jeanne had a chance to answer, Henri butted<br />

in.<br />

‘Indeed I did, Sir. I wanted to be here nice and early<br />

after Jeanne sent word you’d need a groom.’<br />

‘I don’t need a groom,’ countered André in<br />

exasperation. ‘I need a gentleman’s servant.’<br />

‘That’s what I meant, Sir. Instead of brushing down<br />

the horses, I’ll be doing you. There’s no difference. I’ll<br />

be just as careful with you as I was with them.’<br />

undergraduate poetry<br />

The taste of blood is rich and metallic<br />

in the mouth,<br />

Delicious if cut with tequila and lime,<br />

The rouge invisible on ruby red lips.<br />

Now it rages all around,<br />

The golden porcelain charred.<br />

The heat burns,<br />

Those tiny candles<br />

Consumed -<br />

All to nothing.<br />

Now in the mirror the flame sees<br />

what it’s become,<br />

The mirror glows in recognition:<br />

A monster.<br />

Kerry Williams<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Magilligan<br />

Johanna Yacoub

André looked down at his hands,<br />

then at Jeanne and finally at Henri.<br />

‘I’ll give you a week’s trial. Jeanne,<br />

can you find him something more<br />

suitable to wear? Make him take a<br />

bath. Find somewhere for him to<br />

sleep and bring my breakfast. I’m<br />

starving. In fact, send Denise<br />

through right away with a pot of<br />

fresh strong coffee. I’ve had nothing<br />

but lukewarm dishwater for the last<br />

four months.’<br />

He wheeled the chair towards<br />

his room, then stopped and turned<br />

back,<br />

‘And for God’s sake, light the<br />

bloody fires. I’m freezing.’<br />

Jeanne tugged Henri’s sleeve and<br />

led him from the room. As<br />

Magilligan left, André noticed he<br />

was slightly hunched and the line of<br />

his spine skewed to one side. At that<br />

moment, Alexia entered. Henri<br />

stepped back politely to allow her to<br />

pass.<br />

‘Morning, Ma’am,’<br />

He greeted her cheerfully with<br />

his off-balance smile and a slight<br />

nod of his head.<br />

‘I’ll be back to bathe the master in<br />

a moment. He’ll be spanking clean<br />

by the time I’ve finished.’<br />

‘Come on Henri,’ muttered<br />

Jeanne. ‘I’ve got to make you<br />

presentable and set out a few rules<br />

of the house.’<br />

‘You do that, Miss Jeanne. I<br />

won’t mind a bit and if I get it<br />

wrong you can wallop me with that<br />

big stick you hide in the pantry.’<br />

Jeanne pursed her lips and<br />

propelled Henri down the corridor.<br />

Despite his misgivings, André<br />

began to laugh. Alexia looked at<br />

him, her eyes wide with<br />

astonishment and dismay.<br />

‘You haven’t taken him on, have<br />

you? You must be out of your mind.’<br />

‘It’s the gas, Alexia... just keep<br />

telling yourself... your husband was<br />

gassed.’<br />

‘May God help us,’ she moaned<br />

as she collapsed onto the sofa.<br />

‘Well,’ said André, ‘God’s<br />

certainly with Magilligan, so maybe<br />

he’ll adopt us too.’<br />

♣<br />

That other small room behind<br />

the library had become a<br />

building site. Old tarpaulins were<br />

spread over the floor to protect the<br />

parquet and a construction of<br />

planks on trestles provided a raised<br />

walkway round the walls, giving<br />

access to the higher reaches and<br />

ceiling. A wooden ladder leant<br />

against the doorframe, and an old<br />

tea chest with a chipped wood block<br />

over it doubled as a worktable.<br />

Spare brushes bristled from a jar of<br />

turpentine and smaller paint pots<br />

nestled against a large bucket of<br />

white emulsion. Magilligan stirred<br />

this with a broken broomstick,<br />

before pouring the paint into the<br />

smaller pots. They were easier to<br />

manage and, if he did drop a pot, it<br />

wasn’t a disaster. He used his longer<br />

left arm for the painting, although<br />

he was by nature right handed.<br />

Balancing on the trestles, he<br />

dipped the broad brush into the<br />

paint and began covering the walls<br />

of the small bedroom with smooth<br />

strokes of colour. He worked<br />

methodically, tipping into the<br />

cornice below the ceiling then<br />

sweeping down to the skirting<br />

board, which he’d completed the<br />

day before. Hopping on and off the<br />

trestles was tiring, but he was<br />

determined to do a neat job. At the<br />

end of each panel of paint, he<br />

feathered out the edges and<br />

scooped up any drips with the dry<br />

14<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

brush he kept in his overall pocket<br />

for that sole purpose. Then he<br />

wiped over the gloss finish of the<br />

wood, cleaning off stray spatters as<br />

he progressed round the room.<br />

He’d get this second coat on in a<br />

couple of hours, but would leave it<br />

to dry overnight. Many decorators<br />

thought fingertip dry was sufficient<br />

and added the next layer as soon as<br />

possible but he, Magilligan, knew<br />

better. That kind of short cut<br />

produced a patchy result as the real<br />

density of cover only showed when<br />

it had “gone off”, as his father used<br />

to say. It could look perfect at first,<br />

but the flaws soon appeared once<br />

the thorough drying process was<br />

finished.<br />

By the next day, after he’d<br />

touched up those patches where the<br />

under-colour was “grinning”<br />

through, another of his father’s<br />

expressions, it would be ready for<br />

the final application. He’d need to<br />

gloss over the skirting boards once<br />

more, but then he’d be into the first<br />

proper bedroom he’d ever had in his<br />

twenty-eight years. It had a<br />

washbasin with a mirror over it, and<br />

a bathroom further down the hall<br />

was for his sole use.<br />

March wasn’t the best month for<br />

decorating as the cold damp<br />

weather made it hard to leave<br />

windows open, but he needed to<br />

sleep within earshot of André. The<br />

sooner he finished, the quicker he’d<br />

be able to do that. An alternative<br />

had been a bed in André’s room, a<br />

proposal which had not appealed to<br />

anyone, least of all Alexia. She knew<br />

her husband needed quiet privacy<br />

until he was well enough to return<br />

to a more normal life. Alexia liked to<br />

sit with André in the cosy library<br />

and then in his room until as late as<br />

possible before retiring to her own<br />

bedroom on the first floor. The<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Magilligan<br />

Johanna Yacoub

presence of an extra person would have made that<br />

awkward.<br />

She’d also listened carefully to the advice of André’s<br />

doctors. They were united in the opinion that he’d<br />

recover more quickly in a peaceful and familiar<br />

environment. For four years, he’d led an<br />

institutionalised existence. Solitude was the first real<br />

casualty of war and the hospital, Spartan in its facilities,<br />

thrust the distress of devastating wounds into his face<br />

everyday. After his injury, a high level of medication had<br />

been inescapable. Painkillers remained a necessity, but<br />

opiate sedatives had been reduced. These powerful<br />

drugs had eased his initial physical agony and pacified<br />

the beasts dancing in his mind. Now those<br />

psychological horrors, exacerbated by morphine’s<br />

withdrawal symptoms, slipped off their chemical<br />

shackles and began to torment him with renewed<br />

ferocity.<br />

Memories of the battlefield traumatised every<br />

unguarded moment. The screams of wounded and<br />

dying soldiers echoed in André’s head. Foul imaginary<br />

smells plagued his senses, rising even from the food<br />

placed before him, and his hands trembled in the<br />

remembered cacophony of shellfire. Phantasmagoria<br />

filled his room with ghostly faces. Spectres waved from<br />

dark corners and leapt screeching from the folds of<br />

curtains. Spurts of flame from the fire in the grate<br />

became flashes of hallucinatory shell burst, pressing him<br />

into his pillows in terror. His ears filled with the crump<br />

of artillery as wind blustered through the gables of the<br />

old house. Shutters rattled like machine-gun fire and the<br />

cry of an owl howled with the horrific agony of a<br />

dismembered man.<br />

André frequently woke drenched in perspiration, the<br />

nausea rising in his throat as he clutched his burnt face<br />

and groaned with the excruciating pain pulsing through<br />

his absent leg. Magilligan, who was sleeping in the<br />

corridor on a folding camp bed he’d found in the attic,<br />

calmed André as none other could. Squatting on a low<br />

stool by the bed, Magilligan talked to him of races and<br />

horses, of stallions and bloodlines, all spiced with<br />

anecdotes of owners and trainers. He talked and talked<br />

until the phantoms were vanquished by André’s sleep<br />

of utter exhaustion. ‘Even hellhounds get tired,’ said<br />

Magilligan to himself as he slipped noiselessly from the<br />

room until the next sortie of the banshees of battle.<br />

The attic was a wonderland to Magilligan. Three<br />

hundred years of one family’s discarded debris lay<br />

strewn under the beams of the great house. Despatched<br />

up there by Jeanne in his quest for furniture, he’d<br />

15<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

unearthed a cornucopia of rubbish. Impervious to the<br />

startled scuttle of mice, or the rustle of nesting birds in<br />

the eaves, he’d patiently plodded through the spiders’<br />

webs and mounds of dusty droppings to disinter an old<br />

armchair whose stuffing bulged ominously through its<br />

faded upholstery. Later, he’d chanced upon a<br />

serviceable chest of drawers with no apparent trace of<br />

worm, a bed and a wardrobe. He’d had doubts about<br />

the wardrobe, having nothing to hang in it but,<br />

reckoning his fortunes were on an upward trajectory,<br />

decided notwithstanding to bring it down in<br />

anticipation of his future prosperity.<br />

Magilligan, of whom life had expected nothing, was<br />

determined to demonstrate his unacknowledged<br />

qualities. He’d already rigged up a makeshift bell system<br />

from his bedroom to André’s room. Cords, plaited out<br />

of farmyard hemp, were looped along the corridor<br />

through a series of old curtain rings he’d found in a<br />

dilapidated trunk. As he’d touched the silk velvet they’d<br />

once supported, it disintegrated in brittle shreds<br />

between his fingers but the rings were sound, if a trifle<br />

rusty. The bell, decorated with smiling cows’ faces<br />

painted on the white outer enamel and bordered by pink<br />

and lavender pansies, was a souvenir André’s father had<br />

brought back from Switzerland. After enthusiastic<br />

admiration, it had been swiftly banished to attic<br />

purgatory from whence it now re-emerged, resonant<br />

with newfound purpose. The arrangement was rough<br />

and ready, but in these hard times it was the best he’d<br />

been able to do. Above all, it was fit for the task.<br />

He laughed to himself as he slapped on the paint.<br />

‘Me, a gentleman’s gentleman; who’d have ever<br />

thought it?’ he repeated, pinching himself in his pride<br />

and good luck. Sad his parents hadn’t lived to see the<br />

day, he thought, and resolved never to permit their<br />

demons to flow down his throat.<br />

‘Not that I don’t mind a little tipple every now and<br />

then,’ he said, ‘but there’s a time and a place for<br />

everything.’<br />

He dabbed at a corner of the wall to ensure enough<br />

colour was forced into the crease and continued his<br />

monologue, ‘and the whisky bottle has no place on the<br />

breakfast table.’<br />

Another expedition to the attic had produced a pair<br />

of cotton curtains overlooked by the legions of moths<br />

who’d feasted royally on nearly every other fabric they<br />

could sink their insect teeth into. By chance, he fell<br />

upon a couple of threadbare rugs. Clouds of dust<br />

billowed out of them as he’d staggered sneezing into the<br />

<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Lines</strong> Summer 2008<br />

Magilligan<br />

Johanna Yacoub

kitchen, his trophies held high above his head. Jeanne<br />

had screamed,<br />

‘Get those filthy things out of here... out.. out out,’<br />

and shooing him with the broom, had steered him into<br />

the laundry, where they were first bundled with enough<br />

naphthalene to eradicate the moth population of<br />

Champagne. The curtains had washed up quite nicely,<br />

he thought, and could be hung once the paint was dry.<br />

He’d had a problem with the rugs. Rolled up for years,<br />

they were cracked and encrusted with dirt. Magilligan<br />

rigged up a line between two crossbeams in the stables<br />

and, slinging the rugs over it, had gone daily to shake<br />

and beat the grime out of them.<br />

‘It’s not the dust and mildew,’ he’d complained to<br />

Jeanne, ‘They’ve been self-composting for years. There’s<br />

enough muck here to start a flower garden.’<br />

‘What are you going to do about the tears and holes,’<br />

she’d asked.<br />

‘Don’t worry.’ Magilligan wasn’t concerned about the<br />

occasional hole. ‘Isn’t there a saddler in Chalons? He’ll<br />

have strong thread and those big needles with eyes like<br />

snaffle rings. I’ve mended harness, so I can mend a rug.<br />

It won’t look great, but it’ll cover the floor. That’s all I<br />

need.’<br />

Magilligan was excited by the notion of his own<br />

room. He’d always shared with his brothers or with<br />

other lads. On his uncle’s farm in Chalons, a boarded-off<br />

corner of the barn above the horses had been considered<br />

more than adequate for him, although the family lived in<br />

comfort in a large house with spare rooms. Washing<br />

had been at the pump by the kitchen door and his few<br />

possessions were kept rolled in a canvas cloth.<br />

‘No, Magilligan,’ he said. ‘This is not a step<br />

backwards. Finally you’re on your way.’<br />

♣<br />

Charles saw the doors to his kitchen refuge close in<br />

his face. His father’s return to Chateau de<br />

Belsanges opened the house to a stream of visitors for<br />

the first time since the beginning of the war. A<br />

disorientated toddler clinging to Jeanne’s skirts was a<br />

distraction. Too busy to devote time to him as before,<br />

Jeanne now chased him back to his sisters, where he<br />

was equally unwelcome. Violette and Inez resented his<br />

intrusion into their private world of dolls, or jigsaw<br />

puzzles and skipping competitions. A governess taught<br />

them at home and the local priest supplemented<br />

Mademoiselle’s basics with extra mathematics and a<br />

smattering of Latin. There was even talk of sending<br />

16<br />

postgraduate fiction<br />

them to the village school once the war ended. They’d<br />

grown out of Charles. He was no longer the baby<br />

brother they wheeled around the garden in his pram, or<br />

dressed up in their clothes for fun, but an annoying little<br />

boy who broke their playthings and interrupted their<br />

secret games.<br />

His familiar world was crumbling before his puzzled<br />

eyes. Everyday he grew sulkier and more disconsolate.<br />

His tantrums increased in frequency and ferocity and,<br />

to the horror of his mother, he was once again wetting<br />

the bed. Since that first dreadful encounter with his<br />

father, he hadn’t dared approach him. Alexia had tried<br />

to overcome his aversion but her encouragement was<br />

insufficient to quell his irrational fear whenever he saw<br />

the wheelchair. A reassuring grip on his hand and<br />

coaxing words, or promises of special treats, met with<br />

the same spectacular failure as threats and the<br />