Reconceptualization of the Uncertainty in Illness Theory

Reconceptualization of the Uncertainty in Illness Theory

Reconceptualization of the Uncertainty in Illness Theory

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

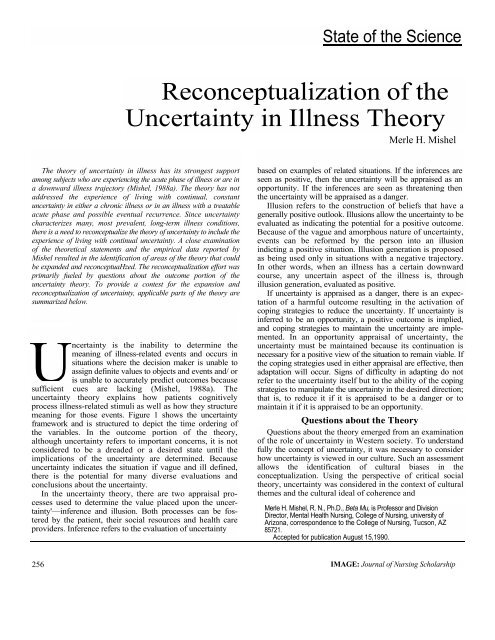

State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science<br />

<strong>Reconceptualization</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Illness</strong> <strong>Theory</strong><br />

The <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> illness has its strongest support<br />

among subjects who are experienc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> acute phase <strong>of</strong> illness or are <strong>in</strong><br />

a downward illness trajectory (Mishel, 1988a). The <strong>the</strong>ory has not<br />

addressed <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g with cont<strong>in</strong>ual, constant<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r a chronic illness or <strong>in</strong> an illness with a treatable<br />

acute phase and possible eventual recurrence. S<strong>in</strong>ce uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

characterizes many, most prevalent, long-term illness conditions,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a need to reconceptualize <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong><br />

experience <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g with cont<strong>in</strong>ual uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. A close exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical statements and <strong>the</strong> empirical data reported by<br />

Mishel resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory that could<br />

be expanded and reconceptuaHzed. The reconceptualization effort was<br />

primarily fueled by questions about <strong>the</strong> outcome portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory. To provide a contest for <strong>the</strong> expansion and<br />

reconceptualization <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, applicable parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory are<br />

summarized below.<br />

<strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> is <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ability to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong><br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> illness-related events and occurs <strong>in</strong><br />

situations where <strong>the</strong> decision maker is unable to<br />

assign def<strong>in</strong>ite values to objects and events and/ or<br />

is unable to accurately predict outcomes because<br />

sufficient cues are lack<strong>in</strong>g (Mishel, 1988a). The<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory expla<strong>in</strong>s how patients cognitively<br />

process illness-related stimuli as well as how <strong>the</strong>y structure<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g for those events. Figure 1 shows <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

framework and is structured to depict <strong>the</strong> time order<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> variables. In <strong>the</strong> outcome portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory,<br />

although uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty refers to important concerns, it is not<br />

considered to be a dreaded or a desired state until <strong>the</strong><br />

implications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty are determ<strong>in</strong>ed. Because<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> situation if vague and ill def<strong>in</strong>ed,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> potential for many diverse evaluations and<br />

conclusions about <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory, <strong>the</strong>re are two appraisal processes<br />

used to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> value placed upon <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty'—<strong>in</strong>ference<br />

and illusion. Both processes can be fostered<br />

by <strong>the</strong> patient, <strong>the</strong>ir social resources and health care<br />

providers. Inference refers to <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

256<br />

Merle H. Mishel<br />

based on examples <strong>of</strong> related situations. If <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ferences are<br />

seen as positive, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty will be appraised as an<br />

opportunity. If <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ferences are seen as threaten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty will be appraised as a danger.<br />

Illusion refers to <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> beliefs that have a<br />

generally positive outlook. Illusions allow <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty to be<br />

evaluated as <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> potential for a positive outcome.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vague and amorphous nature <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty,<br />

events can be reformed by <strong>the</strong> person <strong>in</strong>to an illusion<br />

<strong>in</strong>dict<strong>in</strong>g a positive situation. Illusion generation is proposed<br />

as be<strong>in</strong>g used only <strong>in</strong> situations with a negative trajectory.<br />

In o<strong>the</strong>r words, when an illness has a certa<strong>in</strong> downward<br />

course, any uncerta<strong>in</strong> aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness is, through<br />

illusion generation, evaluated as positive.<br />

If uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is appraised as a danger, <strong>the</strong>re is an expectation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a harmful outcome result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> activation <strong>of</strong><br />

cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies to reduce <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. If uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is<br />

<strong>in</strong>ferred to be an opportunity, a positive outcome is implied,<br />

and cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty are implemented.<br />

In an opportunity appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, <strong>the</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty must be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed because its cont<strong>in</strong>uation is<br />

necessary for a positive view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation to rema<strong>in</strong> viable. If<br />

<strong>the</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies used <strong>in</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r appraisal are effective, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

adaptation will occur. Signs <strong>of</strong> difficulty <strong>in</strong> adapt<strong>in</strong>g do not<br />

refer to <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty itself but to <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

strategies to manipulate <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> desired direction;<br />

that is, to reduce it if it is appraised to be a danger or to<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> it if it is appraised to be an opportunity.<br />

Questions about <strong>the</strong> <strong>Theory</strong><br />

Questions about <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory emerged from an exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> Western society. To understand<br />

fully <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, it was necessary to consider<br />

how uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is viewed <strong>in</strong> our culture. Such an assessment<br />

allows <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> cultural biases <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

conceptualization. Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> perspective <strong>of</strong> critical social<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty was considered <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes and <strong>the</strong> cultural ideal <strong>of</strong> coherence and<br />

Merle H. Mishel, R. N., Ph.D., Beta Mu, is Pr<strong>of</strong>essor and Division<br />

Director, Mental Health Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, College <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, university <strong>of</strong><br />

Arizona, correspondence to <strong>the</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, Tucson, AZ<br />

85721.<br />

Accepted for publication August 15,1990.<br />

IMAGE: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship

State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science.<br />

order <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>trapersonal and <strong>in</strong>terpersonal systems. The<br />

perspective <strong>of</strong> critical social <strong>the</strong>ory is to raise questions about<br />

<strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g social values that support major<br />

conceptualizations <strong>in</strong> science and practice (Allen, 1985). It is<br />

a method by which <strong>the</strong> "established" views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world are<br />

questioned (Thompson, 1987). The basic questions asked<br />

concern<strong>in</strong>guncerta<strong>in</strong>ty were "Why does <strong>the</strong> patient cont<strong>in</strong>ue to<br />

seek certa<strong>in</strong>ty?" "Why is certa<strong>in</strong>ty held <strong>in</strong> such high value <strong>in</strong><br />

this society?" "ls <strong>the</strong> promotion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> goals <strong>of</strong> control,<br />

predictability and certa<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sociohistoric<br />

values <strong>of</strong> this society?"<br />

A parallel, although not a precise one, between <strong>the</strong><br />

nature <strong>of</strong> society and <strong>the</strong> reign<strong>in</strong>g scientific world view has<br />

been posited by Sampson (1989). As a cont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

mechanistic orientation that characterized classical science<br />

and <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factory/consumer society, <strong>the</strong> Western<br />

world portrays events as produced by specific conditions that<br />

<strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple are determ<strong>in</strong>able with precision (T<strong>of</strong>fler, 1984).<br />

The concept <strong>of</strong> rationality <strong>in</strong> this society is grounded <strong>in</strong> a<br />

mechanistic view <strong>of</strong> life (Sampson, 1988). This view <strong>of</strong> life<br />

has ho place for chance or uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> is feared<br />

and accuracy is valued. With predictability and control as<br />

major social values, persons will proceed with culturally<br />

approved behaviors <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> belief that desired outcomes will<br />

be ga<strong>in</strong>ed (Sampson, 1985). The values <strong>of</strong> predictability,<br />

control and certa<strong>in</strong>ty can function to restrict <strong>the</strong> variation <strong>in</strong><br />

behavior <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> society. Individuals take <strong>the</strong> paths that are<br />

promulgated as lead<strong>in</strong>g to obta<strong>in</strong>able secure outcomes; <strong>the</strong>y<br />

pursue certa<strong>in</strong>ty.<br />

Psychological <strong>the</strong>ory supports this mechanistic orientation<br />

by plac<strong>in</strong>g emphasis on concepts such as <strong>in</strong>ternal/ external<br />

control, self-efficacy and learned resourcefulness. The<br />

orientation <strong>of</strong> psychology is toward <strong>the</strong> enhancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

person's ability to obta<strong>in</strong> stable, sure outcomes by <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>stigation <strong>of</strong> specific <strong>in</strong>ternally driven causal behaviors.<br />

Belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> desirability <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> goals and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ability through specific acts is seen as <strong>the</strong> natural view <strong>of</strong><br />

life <strong>in</strong> this <strong>in</strong>dustrialized, consumer-oriented society. The<br />

cultural ideal is <strong>of</strong> an equilibrium concept <strong>of</strong> personhood <strong>in</strong><br />

which order will characterize <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual s life and <strong>the</strong><br />

function<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpersonal systems (Sampson, 1985). Order<br />

and coherence are viewed as be<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed through<br />

emphasis on seek<strong>in</strong>g control and predictability.<br />

The value <strong>of</strong> predictability, control and mastery as <strong>the</strong><br />

natural and normal way <strong>of</strong> life is also seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> health care<br />

sett<strong>in</strong>g, particularly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mechanistic orientation <strong>of</strong><br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e. Medical science, like all fields <strong>of</strong> science, does not<br />

function separately from <strong>the</strong> major values <strong>of</strong> society (T<strong>of</strong>fler,<br />

1984). The expectation <strong>in</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> broader<br />

society, is that specific actions will lead to desirable and<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>able outcomes. Much effort, energy and expense is<br />

put <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> technology that will identify <strong>the</strong><br />

specific causes <strong>of</strong> illness and <strong>the</strong> specific treatment that will<br />

cause <strong>the</strong> desired outcome—a cure (Bursztajen, Fe<strong>in</strong>bloom,<br />

Hamm & Brodsky, 1981). There is <strong>the</strong> expectation <strong>the</strong> cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> illness can be determ<strong>in</strong>ed with certa<strong>in</strong>ty and <strong>the</strong> illness<br />

can be controlled. The goal is to return <strong>the</strong> person to<br />

equilibrium; non-equilibrium is seen as breakdown.<br />

The only <strong>in</strong>formation that is treated as valid is hard,<br />

scientific, objective data (Burztajen, et al., 1981). The<br />

primary source <strong>of</strong> valid <strong>in</strong>formation is under <strong>the</strong> control <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> physician; <strong>the</strong> patient and physician both share this<br />

orientation. The expectation is that cause and effect can be<br />

Volume 22, Number 4, W<strong>in</strong>ter 1990<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed, and success is judged by <strong>the</strong> degree to which<br />

this goal is achieved. Failure at achiev<strong>in</strong>g this is seen as<br />

physician failure, and all attempts are to avert such a disastrous<br />

outcome. Certa<strong>in</strong>ty, control and predictability are <strong>the</strong><br />

desired outcomes; uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is seen as deficient and attempts<br />

are to avoid it or to cast it as a temporary situation.<br />

Based on this view <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> broader society and <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> illness situation, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty has <strong>the</strong> potential to<br />

disrupt <strong>the</strong> person's sense <strong>of</strong> control and direction <strong>of</strong> life as<br />

well as to jeopardize <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> equilibrium.<br />

From this exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cultural attitude toward <strong>the</strong><br />

experience <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, it is apparent <strong>the</strong> present<br />

conceptualization <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty reflects cultural bias <strong>of</strong> a<br />

preference for certa<strong>in</strong>ty and an orientation to <strong>the</strong> achievement<br />

<strong>of</strong> equilibrium as a goal-state. This cultural bias is<br />

reflected <strong>in</strong> three concerns: implicit assumptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ory, conflict<strong>in</strong>g research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and blocks to advanc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory.<br />

Implicit Assumptions<br />

In <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory, adaptation—psychosocial behavior<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> person's normative level <strong>of</strong> function<strong>in</strong>g— is<br />

proposed as <strong>the</strong> end state achieved after cop<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. Adaptation as <strong>the</strong> end state is consistent with<br />

<strong>the</strong> cultural preference for achievement <strong>of</strong> personal order<br />

through atta<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> equilibrium. The question that becomes<br />

apparent is, if a person were to learn how to manage<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty surround<strong>in</strong>g illness, why should this be<br />

conceptualized as achiev<strong>in</strong>g stability with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pre-illness<br />

level <strong>of</strong> function<strong>in</strong>g? The orientation to stability and adaptation<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> present <strong>the</strong>ory does not allow for <strong>the</strong><br />

conceptualization <strong>of</strong> growth and change follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> experience<br />

<strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. In an acute illness situation, learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

how to manage <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty results <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong><br />

this experience <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> new level <strong>of</strong> self-organization and so is<br />

not a return to a previously exist<strong>in</strong>g level <strong>of</strong> function but<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>the</strong> growth result<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> current experience.<br />

In long-term uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, where <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty can't be<br />

managed and persons must live with endur<strong>in</strong>g uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty,<br />

perhaps a new state can be achieved that evolves from what<br />

previously existed.<br />

The idea that manag<strong>in</strong>g short-term uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty and liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with cont<strong>in</strong>ual uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty may result <strong>in</strong> personal growth<br />

leads to consideration <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> person's experience <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty could shift over time. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> model and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory do not address <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> temporal variability, <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

no consideration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nonl<strong>in</strong>ear impact <strong>of</strong> antecedent<br />

variables such as health care providers and social supports on<br />

<strong>the</strong> appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty over time. As many illnesses have<br />

a long-term effect on <strong>in</strong>dividual lives, <strong>the</strong>ories to expla<strong>in</strong><br />

illness-related phenomena need to <strong>in</strong>clude a perspective that<br />

illustrates how <strong>the</strong> phenomena evolve over time. This lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> attention to change reflects <strong>the</strong> cultural bias toward<br />

stability and control. Little attention is given <strong>in</strong> psychological<br />

<strong>the</strong>ories toward exchange between <strong>the</strong> system and <strong>the</strong><br />

environment or to irreversible processes. In qualitative<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigations <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty it was found <strong>the</strong> longer<br />

chronically ill subjects lived with cont<strong>in</strong>ual uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, <strong>the</strong><br />

more positively <strong>the</strong>y evaluated <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty (K<strong>in</strong>g &<br />

Mishel, 1986). This implies <strong>the</strong> appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

evolves over time, which is not accounted for <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory.<br />

257

Conflict<strong>in</strong>g F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

In <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ory, <strong>the</strong> appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as an<br />

opportunity is expected to occur only when <strong>the</strong> situation is<br />

one with a high probability <strong>of</strong> negative uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, an illness<br />

situation with a known downward trajectory. The explanation<br />

for uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty be<strong>in</strong>g appraised as an opportunity <strong>in</strong> such<br />

situations is logical s<strong>in</strong>ce, when <strong>the</strong> alternative is negative<br />

certa<strong>in</strong>ty, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty becomes a preferable state. Limit<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

positive evaluation <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty to a situation <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong><br />

certa<strong>in</strong> outcome <strong>in</strong>dicates progressive deterioration or death<br />

reflects <strong>the</strong> cultural value that uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is an aversive<br />

experience and, except <strong>in</strong> an extreme situation, is def<strong>in</strong>itely<br />

not preferable to certa<strong>in</strong>ty. Although <strong>the</strong>re are f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to<br />

support <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory (Capritto, 1980; Pergr<strong>in</strong>, Mishel &<br />

Murdaugh, 1987; Yarcheski, 1988), <strong>the</strong>re are o<strong>the</strong>r f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

from research based on persons with long-term chronic<br />

illnesses without a downward trajectory that show uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

appraised as a desirable state (K<strong>in</strong>g & Mishel, 1986;<br />

Mishel & Murdaugh, 1987; Mishel, 1988b). S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>se<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs conflict with <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory needs to be<br />

expanded to account for <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> preferable uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

<strong>in</strong> situations o<strong>the</strong>r than those characterized by<br />

negative certa<strong>in</strong>ty.<br />

Theoretical Blocks<br />

The f<strong>in</strong>al concern centers on <strong>the</strong> appraisal-cop<strong>in</strong>g section <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ory. In <strong>the</strong> model, opportunity and danger are<br />

parallel to each o<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> patient chooses one and<br />

only one path. Although this may be appropriate for certa<strong>in</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical situations, it may not accurately reflect <strong>the</strong><br />

fluctuations that occur over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> illness and may not<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> long-term illness situation. Over time, an appraisal<br />

<strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as a danger may evolve <strong>in</strong>to appraisal <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as a positive experience. Selection <strong>of</strong> only one type<br />

<strong>of</strong> appraisal negates <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> appraisal as a process that<br />

fluctuates over time. Instead, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory reflects a<br />

mechanistic orientation to a specific state and not a process.<br />

Here, too, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory needs reformulation to address <strong>the</strong><br />

appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as an evolv<strong>in</strong>g process.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong>se questions and concerns, <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong> reformulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory was not to disregard <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

statements and l<strong>in</strong>kages but to expand <strong>the</strong>m to<br />

account for a perspective <strong>of</strong> growth and self-organization as<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g with uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> an<br />

equilibrium-stability view <strong>of</strong> adaptation. The expansion <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory is done to <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>of</strong> (a) change<br />

FIGURE 1 Outcome portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>Illness</strong> model<br />

258<br />

State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science<br />

over time, (b) evolution <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> appraisal <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, (c)<br />

emphasis on <strong>the</strong> person as an open system <strong>in</strong>terchang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

energy with <strong>the</strong> environment and (d) an orientation toward<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased complexity ra<strong>the</strong>r than an equilibrium ideal. The<br />

reconceptualization effort is directed primarily toward expand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory to <strong>in</strong>crease its applicability to<br />

<strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> persons liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Western society under<br />

conditions where (a) uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is a cont<strong>in</strong>ual experience<br />

that extends over years and (b) <strong>the</strong> illness is ei<strong>the</strong>r chronic<br />

with remissions and exacerbations or potentially life threaten<strong>in</strong>g<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g a treatable acute phase with an unknown<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> recurrence or extension.<br />

<strong>Reconceptualization</strong> Approach<br />

The approach to reformulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory<br />

used <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory derivation as described by Walker<br />

and Avant (1989) to identify a parent <strong>the</strong>ory that addressed<br />

<strong>the</strong> four <strong>the</strong>mes identified as <strong>the</strong> focus for <strong>the</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory. Walker and Avant def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>ory derivation as<br />

"<strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g analogy to obta<strong>in</strong> explanations or<br />

predictions about phenomenon <strong>in</strong> one field from <strong>the</strong> explanations<br />

or predictions <strong>in</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r field" (p. 163). The<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory derivation process <strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>the</strong> steps <strong>of</strong> not<strong>in</strong>g similar<br />

dimensions <strong>of</strong> a phenomenon <strong>in</strong> field one and redef<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation from field one to field two. Redef<strong>in</strong>ition is<br />

accomplished <strong>in</strong> a way that is compatible with and advances<br />

<strong>the</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> phenomenon <strong>in</strong> field two. However,<br />

identify<strong>in</strong>g relevant <strong>the</strong>ory and mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> analogy<br />

require creativity, imag<strong>in</strong>ation and <strong>in</strong>tensive concentration to<br />

conceptualize <strong>the</strong> rationale for <strong>the</strong> transposition <strong>of</strong> con-ten t<br />

and structure. Because <strong>the</strong> task was not to ga<strong>in</strong> knowledge about a<br />

new topic but to clarify <strong>the</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory<br />

targeted for modification, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory derivation activity<br />

undertaken was somewhat different than that just described.<br />

Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory was selected as <strong>the</strong> parent <strong>the</strong>ory because it<br />

deals with open systems and is <strong>the</strong>refore able to address <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between systems and <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>teraction with <strong>the</strong><br />

outside forces. Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory also speaks to <strong>the</strong> activities <strong>of</strong> a<br />

system when <strong>the</strong> system is outside its usual rout<strong>in</strong>e function<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

As Walker and Avant (1989) note, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>orist is free to<br />

select <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory that best fit <strong>the</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

formulation. Therefore, selected aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> content and<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory were used as <strong>the</strong> basis for derivation.<br />

Chaos <strong>Theory</strong><br />

The concepts <strong>in</strong> chaos <strong>the</strong>ory differ from <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

focus <strong>of</strong> science on stability, order, uniformity, equilibrium<br />

and concern with closed systems and l<strong>in</strong>ear relationships;<br />

chaos <strong>the</strong>ory shifts attention to disorder, <strong>in</strong>stability, diversity,<br />

disequilibrium, nonl<strong>in</strong>ear relationships and temporality,<br />

which are part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> healthy variability <strong>of</strong> a system (Pool,<br />

1989). Chaos was described by Pool as "determ<strong>in</strong>istic randomness"<br />

because, even though a system may stay with<strong>in</strong><br />

certa<strong>in</strong> limits, its behavior can appear random. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

Pool, chaos is determ<strong>in</strong>istic because it is generated from<br />

<strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic causes and not from extraneous noise; randomness<br />

refers to <strong>the</strong> irregular and complex behavior that is demonstrated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> system. Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory deals with concepts<br />

such as far-from-equilibrium systems, critical values, nonl<strong>in</strong>ear<br />

transformations and bifurcation po<strong>in</strong>ts. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to chaos<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory, Prigog<strong>in</strong>e and Stengers (1984) stressed all systems<br />

conta<strong>in</strong> subsystems that are cont<strong>in</strong>ually fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g. At times<br />

IMAGE: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship

State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science.<br />

a s<strong>in</strong>gle fluctuation or a comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m can become so<br />

powerful through feedback mechanisms with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y shatter <strong>the</strong> organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> system. As Pool<br />

suggested chaotic processes are complicated and unpredictable;<br />

yet <strong>the</strong>y result determ<strong>in</strong>istically from <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong><br />

system regulates its process ra<strong>the</strong>r than from random fluctuations.<br />

Chaos provides a healthy variability <strong>in</strong> a system's<br />

response to a variety <strong>of</strong> stimuli.<br />

Although changes can occur <strong>in</strong> systems that are near<br />

equilibrium, it is <strong>the</strong> far-from-equilibrium systems that are<br />

<strong>the</strong> focus here. In far-from-equilibrium conditions, <strong>the</strong><br />

sensitivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial condition is such that small changes<br />

yield huge effects, and <strong>the</strong> system reorganizes itself <strong>in</strong> multiple<br />

ways. Fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system can become so powerful<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y shatter <strong>the</strong> preexist<strong>in</strong>g organization. In cases<br />

where <strong>in</strong>stability is possible, one has to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> distance<br />

or threshold at which fluctuations exceed <strong>the</strong> critical<br />

value to lead to new behavior. Fluctuations may lie below or<br />

above a critical value. In some situations critical value is<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by communication with <strong>the</strong> outside world and<br />

can, depend<strong>in</strong>g on that communication, be destroyed or<br />

can spread throughout <strong>the</strong> entire system (Prigog<strong>in</strong>e &<br />

Stengers, 1984).<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conditions that promotes <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> a<br />

fluctuation with<strong>in</strong> a system and possess <strong>the</strong> seeds <strong>of</strong> chaos is<br />

<strong>the</strong> positive feedback process <strong>of</strong> non-l<strong>in</strong>ear reactions. In<br />

<strong>the</strong>se reactions, <strong>the</strong> reaction product has a feedback action on<br />

itself (Brent, 1978). These auto-catalytic processes result <strong>in</strong> a<br />

product whose presence encourages fur<strong>the</strong>r production <strong>of</strong><br />

itself. In this way it is possible to force <strong>the</strong> system <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong><br />

chaotic regime by augment<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> concentration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

fluctuation through <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parameter <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> positive feedback. As <strong>the</strong> fluctuations ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> strength,<br />

entropy is produced.<br />

Entropy <strong>in</strong> chaos <strong>the</strong>ory refers to <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> disorder or<br />

disorganization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system. The production <strong>of</strong> entropy is<br />

calculated from <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> flux (fluctuation) and <strong>the</strong><br />

forces. As this entropy <strong>in</strong>creases, it may surpass <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> system to <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>the</strong> disorder. If <strong>the</strong> fluctuation<br />

exceeds <strong>the</strong> critical value, <strong>the</strong> threshold <strong>of</strong> stability or bifurcation<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t is reached. At <strong>the</strong> bifurcation po<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>the</strong><br />

system becomes unstable <strong>in</strong> respect to fluctuations. It is<br />

unknown where <strong>the</strong> system will go when it reaches bifurcation,<br />

although this can be <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

system as well as by boundary conditions such as temperature or<br />

concentration <strong>of</strong> chemical substances with<strong>in</strong> a system.<br />

Also, <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> fluctuation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system will affect <strong>the</strong><br />

choice <strong>of</strong> bifurcation branch <strong>the</strong> system may follow. External<br />

fields are ano<strong>the</strong>r source <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence on <strong>the</strong> behaviors<br />

available to far-from-equilibrium systems s<strong>in</strong>ce such systems<br />

are highly sensitive to fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

(Nicolis & Prigog<strong>in</strong>e, 1977).<br />

At <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> bifurcation, although <strong>the</strong> system appears<br />

highly unstable with giant fluctuations, <strong>in</strong>stability is only at<br />

<strong>the</strong> macroscopic level. At <strong>the</strong> microscopic level <strong>the</strong> fluctuations<br />

show pattern<strong>in</strong>g that evolves toward a new position. In<br />

what appears to be random, an "attractor" functions like a<br />

magnet for <strong>the</strong> fluctuations and causes <strong>the</strong> pattern<strong>in</strong>g (Gleick,<br />

1987); a process <strong>of</strong> self-organization occurs (Prigog<strong>in</strong>e &<br />

Stengers, 1984). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Prigog<strong>in</strong>e and Stengers entropy is<br />

seen as <strong>the</strong> progenitor <strong>of</strong> order. The giant fluctuation<br />

caus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> entropy is stabilized through energy exchanges<br />

with <strong>the</strong> outside world, which, <strong>in</strong> turn, <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>the</strong> new<br />

Volume 22, Number 4, W<strong>in</strong>ter 1990<br />

level <strong>of</strong> stabilization or self-organization. The <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> system with <strong>the</strong> outside world may become <strong>the</strong> start<strong>in</strong>g<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t for <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> dissipative structures. Dissipative<br />

structures are new forms <strong>of</strong> organization that ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves by dissipat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir disorder <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> external<br />

world <strong>in</strong> exchange for order. All dissipative structures are a<br />

reflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disequilibrium produc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m. Out <strong>of</strong><br />

disorder rises order.<br />

Chaos <strong>Theory</strong> and <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Illness</strong><br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to chaos <strong>the</strong>ory, activity lead<strong>in</strong>g to new levels <strong>of</strong><br />

self-organization occurs with<strong>in</strong> systems that are far-fromequilibrium.<br />

Because such systems are open, exchang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

both energy and matter with <strong>the</strong> environment (Brent, 1978),<br />

most biological and social systems fit <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> farfrom-equilibrium<br />

systems. Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory states that whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

chaos will be evidenced depends on die <strong>in</strong>itial condition<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a system. In far-from-equilibrium systems, fluctuations<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system function to enhance <strong>the</strong> system's receptivity<br />

to change. In <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> chaos <strong>the</strong>ory to<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> illness, it is proposed <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty surround<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a chronic or life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g condition qualifies as a<br />

sufficient fluctuation to threaten <strong>the</strong> preexist<strong>in</strong>g organization<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> person, a far-from-equilibrium system.<br />

With<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> conf<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> illness, frequent concerns are<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

about <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> treatment, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> illness on one's life and uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about <strong>the</strong> ability to<br />

pursue life's dreams and ambitions. In a life-style organized<br />

around enhanc<strong>in</strong>g predictability and control, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

has been found to prevent <strong>the</strong> person from hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation necessary for controll<strong>in</strong>g events (Staub & Keilett,<br />

1972; Staub, Tursky & Schwartz, 1971). In cl<strong>in</strong>ical studies,<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty has been disruptive <strong>of</strong> important life areas<br />

(Mishel, Hostetter, K<strong>in</strong>g & Graham, 1984) and associated<br />

with psychological distress (Mishel, 1988b). <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> has<br />

been found to reduce <strong>the</strong> person's sense <strong>of</strong> mastery over <strong>the</strong><br />

events, to enhance <strong>the</strong> sense <strong>of</strong> danger (Mishel, 1988b) and to<br />

weaken <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> learned resourcefulness (Braden,<br />

1990). Both cl<strong>in</strong>ical and laboratory studies <strong>in</strong>dicate that<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is an aversive experience for persons oriented<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> enhancement <strong>of</strong> predictability for achiev<strong>in</strong>g<br />

control.<br />

<strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> <strong>in</strong> illness is viewed as a fluctuation that beg<strong>in</strong>s<br />

<strong>in</strong> only one part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human system and accord<strong>in</strong>g to chaos<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory, can ei<strong>the</strong>r regress and cause no particular disruption or<br />

spread to <strong>the</strong> whole system. As uncerta<strong>in</strong> disease related or<br />

illness related factors are <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> person's life <strong>the</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty competes with <strong>the</strong> person's previous mode <strong>of</strong><br />

function<strong>in</strong>g. If <strong>in</strong>dividuals could conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty so it<br />

did not <strong>in</strong>vade multiple aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir lives, <strong>the</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty would not be sufficient to disrupt an on-go<strong>in</strong>g<br />

life pattern. But if aspects <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty were to multiply so<br />

rapidly <strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>vaded significant aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> person's be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and life, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty would move <strong>the</strong><br />

person, a far-from-equilibrium system, past a critical value<br />

where <strong>the</strong> stability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> personal system or its <strong>in</strong>dependence<br />

from disruptive forces could no longer be taken for granted.<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to chaos <strong>the</strong>ory, <strong>in</strong> order for <strong>the</strong> fluctuation to<br />

ga<strong>in</strong> sufficient force to move <strong>the</strong> system, it must function as a<br />

catalytic loop <strong>in</strong> a nonl<strong>in</strong>ear reaction with a sufficient<br />

feedback action on itself, thus <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g its concentration<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system. The force <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty can become<br />

259

concentrated s<strong>in</strong>ce uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is a source <strong>of</strong> a nonl<strong>in</strong>ear<br />

reaction. The existence <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> one area <strong>of</strong> illness<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten feeds back on itself and generates fur<strong>the</strong>r uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r illness-related events. For example, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about<br />

how a treatment works to combat an illness creates<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ties surround<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> reasons for symptoms that<br />

exist. Are <strong>the</strong> symptoms <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al illness or<br />

residuals <strong>of</strong> treatment? Also, <strong>in</strong> illness lack<strong>in</strong>g a specific<br />

etiology, neutral elements <strong>of</strong> a person's life become imbued<br />

with <strong>the</strong> potential for caus<strong>in</strong>g illness exacerbation. Because<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> illness can become <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> its own syn<strong>the</strong>sis,<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to chaos <strong>the</strong>ory, it qualifies as a catalytic loop. As<br />

<strong>the</strong> concentration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty expands, it can exceed<br />

<strong>the</strong> person's level <strong>of</strong> tolerance—<strong>the</strong> critical threshold caus<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> personal system to become unstable. The degree <strong>of</strong><br />

disorder or entropy is calculated from <strong>the</strong> flux and <strong>the</strong> forces.<br />

Flux equates with <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, and forces are <strong>the</strong><br />

significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> life areas <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty.<br />

The significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se areas and <strong>the</strong>ir priority <strong>in</strong> one's life<br />

would account for <strong>the</strong> force with which uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty impacts on<br />

<strong>the</strong> person's life.<br />

Liv<strong>in</strong>g with Cont<strong>in</strong>ual <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong><br />

If <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty endures and cannot be elim<strong>in</strong>ated, <strong>the</strong><br />

length <strong>of</strong> time <strong>the</strong> flux <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty exists is likely to<br />

enhance <strong>the</strong> sense <strong>of</strong> disorganization, promot<strong>in</strong>g a high<br />

level <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stability. Abid<strong>in</strong>g uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty can dismantle <strong>the</strong><br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g cognitive structures that give mean<strong>in</strong>g to everyday<br />

events. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Antonovsky (1987), for life to appear<br />

coherent, <strong>the</strong> events compris<strong>in</strong>g one's life must be structured,<br />

ordered and predictable. When <strong>the</strong> stimuli associated<br />

with illness, treatment and recovery are vague, ill-def<strong>in</strong>ed,<br />

probabilistic, ambiguous and unpredictable, (i.e., uncerta<strong>in</strong>)<br />

<strong>the</strong> sense <strong>of</strong> coherence is lost. This loss <strong>of</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

throws <strong>the</strong> person <strong>in</strong>to a state <strong>of</strong> confusion and disorganization.<br />

The turbulence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> system demonstrative <strong>of</strong> chaos is<br />

proposed to be proportional to <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty experienced by<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient.<br />

The uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness situation is <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> a<br />

flux that shifts <strong>the</strong> person from an orig<strong>in</strong>al position through a<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> bifurcation toward a new state. Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

predom<strong>in</strong>ant sense and display <strong>of</strong> disorder, <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

new state is not observable. At <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> disorder at <strong>the</strong><br />

macroscopic level, when <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty appears <strong>the</strong> highest,<br />

some early structur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a new value system is occurr<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

imperceivable but exist<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> microscopic level. Thus<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty may be a condition under which a person can<br />

make a transition dur<strong>in</strong>g illness from one perspective <strong>of</strong> life<br />

toward a new, higher order, a more complex orientation<br />

toward life.<br />

In all cases where this conceptualization is applied, one<br />

has to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> necessary threshold <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

plus <strong>the</strong> essential time period for <strong>the</strong> flux to lead to a new<br />

perspective on life. It is likely this will differ across <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

and cl<strong>in</strong>ical situations. Yet <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty will <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong><br />

development <strong>of</strong> this perspective <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> person because chaos<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory predicts <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fluctuation <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>the</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g order. The new view <strong>of</strong> life will also develop from<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction with and exchange between <strong>the</strong> person and <strong>the</strong><br />

external environment. Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory states history, boundary<br />

conditions and external fields will <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong> system's<br />

development <strong>of</strong> a new state <strong>of</strong> more complex order. Factors<br />

that <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new orientation toward<br />

260<br />

_ State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science<br />

life <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ill person at <strong>the</strong> peak level <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stability are prior<br />

life experience, physiological status, social resources and<br />

health care providers.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> styl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new perspective on life, a dynamic<br />

process occurs, with <strong>in</strong>put from <strong>the</strong> social resources and<br />

health care providers. Patients attempt to <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>the</strong><br />

experience <strong>of</strong> chronic uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir self-structure.<br />

The process <strong>in</strong>s natural one unless it is blocked or prolonged.<br />

Horowitz (1979) <strong>of</strong>fers <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> "completion<br />

tendency," which seems to expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrative cognitive<br />

process. The patient cognitively reworks <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty from be<strong>in</strong>g aversive <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g opportunistic by<br />

gradual approximation. The cognitive tasks <strong>of</strong> assimilation<br />

and accommodation cont<strong>in</strong>ue until <strong>the</strong> cognitive models<br />

change so that reality and models achieve harmony. At<br />

completion, <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

self and <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world (Green, Wilson & L<strong>in</strong>dy,<br />

1985). This process is natural and is fueled by <strong>the</strong> attractor <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> human need to cognitively structure life events.<br />

Outcome <strong>of</strong> Chronic <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong>—A New View<br />

The uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty that early <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness was <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong><br />

fluctuation and disruption later <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness becomes <strong>the</strong><br />

foundation on which <strong>the</strong> new sense <strong>of</strong> order is constructed.<br />

The uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is used by <strong>in</strong>dividuals as <strong>the</strong> basis for selforganization<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y reformulate <strong>the</strong>ir view <strong>of</strong> life. The new<br />

state <strong>of</strong> order has a new world view <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g probabilistic<br />

and conditional th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g- This new world view is not <strong>the</strong><br />

positively oriented illusions generated from uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as<br />

described <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> illness.<br />

To develop probabilistic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

has to be accepted as <strong>the</strong> natural rhythm to life. The<br />

expectation <strong>of</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ual certa<strong>in</strong>ty and predictability is<br />

abandoned as a part <strong>of</strong> reality. Belief <strong>in</strong> a conditional world<br />

opens up <strong>the</strong> consideration <strong>of</strong> multiple possibilities s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

certa<strong>in</strong>ty is not absolute. When probabilistic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

used, events are seen as <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> various cont<strong>in</strong>gencies,<br />

and differentially effective responses are considered. Effectiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> one's actions is appraised <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> vary<strong>in</strong>g<br />

probabilities for success. There is a new ability to focus on<br />

multiple alternatives, choices and possibilities; to reevaluate<br />

what is important <strong>in</strong> life; to consider variations <strong>in</strong> personal<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestment; to appreciate <strong>the</strong> fragility and impermanence <strong>of</strong><br />

life situations. The new view <strong>of</strong> life allows <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty to be changed from danger to opportunity.<br />

In chaos <strong>the</strong>ory, when <strong>the</strong> system self-organizes a newlevel<br />

<strong>of</strong> complexity, <strong>the</strong> structure is termed "dissipative"<br />

because, to achieve a new level <strong>of</strong> stability, it exchanges<br />

disorder from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal system to <strong>the</strong> environment. With<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> illness situation a parallel activity occurs. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong><br />

person with a new orientation toward life is a far-fromequilibrium<br />

system, <strong>the</strong> new view <strong>of</strong> life is fragile and it is<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed by cont<strong>in</strong>ually express<strong>in</strong>g a negative appraisal <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> environment <strong>in</strong> exchange for <strong>the</strong> view<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty allows for multiple choices; thus uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is<br />

an opportunity. The person functions to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> this new<br />

view <strong>of</strong> life through <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two environmental forces<br />

<strong>of</strong> support resources and health care providers.<br />

For this new orientation toward life to be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed,<br />

both <strong>the</strong> social resources <strong>in</strong> a person's life and <strong>the</strong> health<br />

care providers must believe <strong>in</strong> a probabilistic paradigm<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than a mechanistic paradigm. If <strong>the</strong>se persons share<br />

such a view, <strong>the</strong>y can work with <strong>the</strong> patient to move with <strong>the</strong><br />

IMAGE: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship

State <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Science<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty and to use it as a positive force <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient's<br />

life. In <strong>the</strong> mechanistic paradigm, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is viewed as<br />

<strong>the</strong> enemy that must be elim<strong>in</strong>ated. The assumption is all<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness can be l<strong>in</strong>early determ<strong>in</strong>ed. In this<br />

paradigm, health care providers cannot jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>to a partnership<br />

with <strong>the</strong> patient to use <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as a force for<br />

evolution. In <strong>the</strong> probabilistic paradigm <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is<br />

viewed as natural: uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is an <strong>in</strong>herent part <strong>of</strong> reality,<br />

and life is not assumed to be determ<strong>in</strong>ate with precision.<br />

When family, friends and health care providers support a<br />

probabilistic view <strong>of</strong> life and <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> illness, <strong>the</strong> acknowledgment<br />

<strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty removes a barrier to trust. The<br />

realization that uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> an unescapably part <strong>of</strong> reality<br />

can motivate people to work at creat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> trust<strong>in</strong>g relationships<br />

and mutual support necessary <strong>in</strong> a world where no<br />

one can have a sure or f<strong>in</strong>al answer. Accept<strong>in</strong>g uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

opens <strong>the</strong> door to consider multiple possibilities s<strong>in</strong>ce noth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is certa<strong>in</strong> or universal (Burszajen et al., 1981).<br />

With<strong>in</strong> this conceptualization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> chronic illness, <strong>the</strong>re are four situations <strong>in</strong><br />

which <strong>the</strong> reevaluation <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty can be blocked or<br />

prolonged, thus threaten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> viability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dissipative<br />

structure. The first situation occurs when <strong>the</strong> patient's<br />

supportive resources do not promote a probabilistic or<br />

conditional view <strong>of</strong> life. The second situation occurs when<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient is <strong>the</strong> major caretaker <strong>of</strong> significant o<strong>the</strong>rs and<br />

delays <strong>the</strong>ir psychological response to <strong>the</strong>ir diagnosis and<br />

treatment. The delayed response to <strong>the</strong>ir experience blocks<br />

<strong>the</strong>m from fully activat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>teractions with supportive o<strong>the</strong>rs to<br />

facilitate restructur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ly. The third<br />

situation occurs <strong>in</strong> patients who are isolated from<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction with social resources. These patients have less<br />

opportunity to obta<strong>in</strong> assistance <strong>in</strong> structur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> new view <strong>of</strong><br />

life to dissipate <strong>the</strong> sense <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as aversive. The<br />

fourth block<strong>in</strong>g situation occurs when <strong>the</strong> patient's health<br />

care providers ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a persistent search for predictability<br />

and certa<strong>in</strong>ty. When patients are treated by health care<br />

providers who fail to acknowledge <strong>the</strong> natural existence <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, <strong>the</strong> patient ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> view uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty is an<br />

anomaly that must be removed.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration and accommodation is<br />

blocked or prolonged, <strong>the</strong> behavior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> person will<br />

resemble that seen <strong>in</strong> posttraumatic stress disorders, a condition<br />

caused by exposure to catastrophic uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty and<br />

unpredictability. The evolution <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

aversive cont<strong>in</strong>ues to reverberate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> person, creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

behaviors such as uncontrollable and emotionally distress<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

<strong>in</strong>trusive thoughts or images connected with <strong>the</strong> aversive<br />

events, alternat<strong>in</strong>g with psychic numb<strong>in</strong>g to shield <strong>the</strong> person<br />

from <strong>the</strong> trauma and a purposeful avoidance <strong>of</strong> situations,<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals, thoughts and feel<strong>in</strong>gs about <strong>the</strong> experience (Green,<br />

Grace & L<strong>in</strong>dy, 1988). This response is cyclic with clusters <strong>of</strong><br />

symptoms fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g differtially over time (Green, L<strong>in</strong>dy &<br />

Grace, 1985; Green et al., 1985). Although this complex <strong>of</strong><br />

behaviors will be demonstrated <strong>in</strong>itially when uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

disrupts <strong>the</strong> person's life, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensity and duration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

symptom complex will be prolonged and magnified <strong>in</strong> any<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four situations described above.<br />

Probabilistic Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Feedback from <strong>the</strong> health care providers promot<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

probabilistic world view encourages <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> a<br />

new sense <strong>of</strong> order <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> person. Current nurs<strong>in</strong>g practice<br />

Volume 22, Number 4, W<strong>in</strong>ter 1990<br />

<strong>in</strong>volves activities that are consistent with this world view.<br />

Nurs<strong>in</strong>g activities with <strong>the</strong> chronically ill function currently to<br />

promote probabilistic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g when nurses help <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

to consider multiple new ways to accomplish valued activities<br />

or consider alternatives <strong>in</strong> adjust<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g nature <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> illness or foster <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>the</strong>re are many factors<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> patient's response to treatment. Nurs<strong>in</strong>g<br />

functions to facilitate <strong>the</strong> patient's evaluation <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty<br />

and promote a probabilistic view <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

When we encourage patients to consider alternatives and<br />

choices as possibilities, we are teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m to alter <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g from mechanistic to probabilistic. This new view <strong>of</strong><br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as a natural phenomena is a new view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

world <strong>in</strong> which <strong>in</strong>stability and fluctuation are natural and<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> person's range <strong>of</strong> possibilities. When nurses<br />

jo<strong>in</strong> with patients <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> probabilistic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong><br />

energy exchange between <strong>the</strong> patient and <strong>the</strong> external<br />

resources ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> dissipative structure. When patients<br />

become adherents <strong>of</strong> probabilistic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>y seem to<br />

select health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals who will jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong> this<br />

view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

While this new view <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty rema<strong>in</strong>sat <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

level without empirical support, <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty as<br />

lead<strong>in</strong>g to more possibilities and new patterns <strong>of</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>gencies<br />

is be<strong>in</strong>g considered not only <strong>in</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g but also <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> current psychological literature on control (Strickland,<br />

1989). The beneficial aspects <strong>of</strong> predictability and its related<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> control are be<strong>in</strong>g called <strong>in</strong>to question (Piper &<br />

Langer, 1986). Newer <strong>the</strong>ories <strong>of</strong> cognitive process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

consider that to generate differentially effective responses, a<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty may be essential (Piper &<br />

Langer, 1986). Creativity may require a lett<strong>in</strong>g go <strong>of</strong> conventional<br />

ways and creat<strong>in</strong>g new cont<strong>in</strong>gencies out <strong>of</strong><br />

seem<strong>in</strong>gly unrelated situations that are not completely<br />

predictable. Perhaps our emphasis on logical, l<strong>in</strong>ear th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

which is a mechanistic world view, has <strong>in</strong>advertently promoted<br />

<strong>in</strong>flexibility and a commitment to determ<strong>in</strong>ism <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

chronically ill that precludes consideration <strong>of</strong> a conditional<br />

world view. The reformulization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>the</strong>ory<br />

has embraced this view.<br />

References<br />

Alien, D. G. (1985). Nurs<strong>in</strong>g research and social control; Alternative models <strong>of</strong> science<br />

that emphasize understand<strong>in</strong>g and emancipation. Image: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Scholarship, 17. 58-64. Amonovsky. A. (1987). Unravel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mystery <strong>of</strong> health: How<br />

people manage stress<br />

and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Braden, C.J. (1990). Learned self-help<br />

response to chronic illness experience: A test<br />

<strong>of</strong> three alternative <strong>the</strong>ories. Scholarly Inquiry for Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Practice, 4(1), 23-41.<br />

Brent, S. B. (1978). Prigog<strong>in</strong>e's model for self-organization <strong>in</strong> nonequilibrium<br />

systems. Human Development, 21, 374-387. Bursztajen, H., Fe<strong>in</strong>bloom, R.I., Hamm, R.<br />

M, & Broadsky, A. (1981). Medical choices,<br />

medical chances. New York: Delacorte. Capritto, K. (1980). The effect <strong>of</strong> perceived<br />

ambiguity on adherence to <strong>the</strong> dietary<br />

regimen <strong>in</strong> chronic hemodialysis. Unpublished master's <strong>the</strong>sis, California State<br />

University at Los Angeles.<br />

Gleick,J. (1987). Chaos: Mak<strong>in</strong>g a new science. New York: Pengu<strong>in</strong> Books. Green, B.<br />

L., Grace, M. C., & L<strong>in</strong>dy, J. D. (1988). Treatment efficacy and cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

implications. InJ. D. L<strong>in</strong>dy (Ed.), Vietnam: A casebook (pp. 292-312). New York;<br />

Brunner/Mazel. Green, B. L., L<strong>in</strong>dy,J. D. & Grace, M.C. (1985). Posttraumatic stress<br />

disorder: Toward<br />

DSM-EV. The Journal <strong>of</strong> Nervous and Menial Disease, 173,406-411. Green, B. L.,<br />

Wilson J. P. Sc L<strong>in</strong>dy, J. D. (1985). Conceptualiz<strong>in</strong>g post traumatic stress<br />

disorder: A psychosocial approach. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: The<br />

study and treatment <strong>of</strong> posttraumatic stress disorder (pp. 53-69). New York:<br />

Br unne r/Mazel.<br />

261

Horowitz, M. ). (1979). Psychological response to serious life events. In V. Hamilton &<br />

D. M. Warburton (Eds.), Human stress and cognition: An <strong>in</strong>formation process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

approach. New York: Wiley,<br />

K<strong>in</strong>g. B., & Mishel, M. (1986, April). <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> appraisal and management <strong>in</strong><br />

chronic illness. Paper presented at <strong>the</strong> N<strong>in</strong>eteenth Communicat<strong>in</strong>g Nurs<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Research Conference, Western Society for Research <strong>in</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, Portland, Oregon.<br />

Mishel,M.H. (1988a). <strong>Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty</strong> <strong>in</strong> illness. Image: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship, 4,<br />

225-232.<br />

Mishel, M.H. (198Sb, April). Cop<strong>in</strong>g with uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong> illness situations. Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>of</strong> Conference: Stress, cop<strong>in</strong>g processes, and health outcomes: New directions <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ory development and research (pp. 51-84). Rochester: Sigma Theta Tau<br />

International, Epsilon Xi chapter, University <strong>of</strong> Rochester.<br />

Mishel, M. H., Hosteller, K<strong>in</strong>g, B., & Graham, V. (1984). Predictors <strong>of</strong> psychosocial<br />

adjustment <strong>in</strong> patients newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer. Cancer Nurs<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

7, 291-299.<br />

Misbel, M. H., & Murdaugh, C. L. (1987). Family experiences with heart transplantation:<br />

Redesign<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dream. Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Research, 36, 332-338.<br />

Nicolis, G., & Prigog<strong>in</strong>e, I. (1977). Self-organization <strong>in</strong> nonequilibrium system New<br />