The dissertation of Kelley, IHM, MS_________________ entitled ...

The dissertation of Kelley, IHM, MS_________________ entitled ...

The dissertation of Kelley, IHM, MS_________________ entitled ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

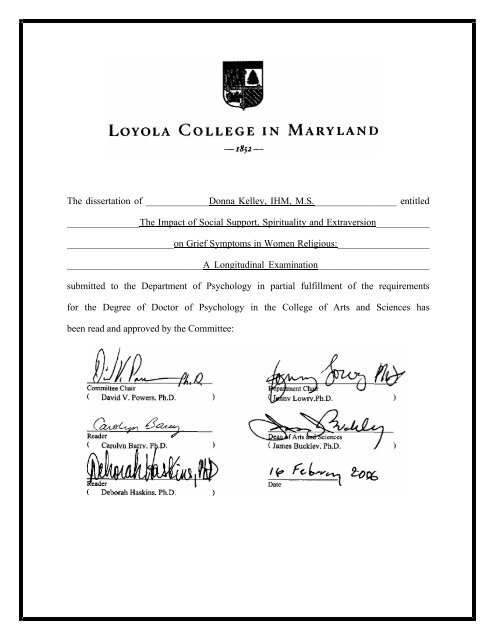

<strong>The</strong> <strong>dissertation</strong> <strong>of</strong> _____________Donna <strong>Kelley</strong>, <strong>IHM</strong>, M.S._________________ <strong>entitled</strong><br />

_______________<strong>The</strong> Impact <strong>of</strong> Social Support, Spirituality and Extraversion___________<br />

______________________on Grief Symptoms in Women Religious:___________________<br />

____________________________A Longitudinal Examination_______________________<br />

submitted to the Department <strong>of</strong> Psychology in partial fulfillment <strong>of</strong> the requirements<br />

for the Degree <strong>of</strong> Doctor <strong>of</strong> Psychology in the College <strong>of</strong> Arts and Sciences has<br />

been read and approved by the Committee:

Dissertation/<strong>The</strong>sis Digitization Permission<br />

<strong>The</strong> Loyola/Notre Dame Library has embarked on a project to digitize all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>dissertation</strong>s produced at Loyola College and the College <strong>of</strong> Notre Dame in their doctoral<br />

programs and theses written for masters degrees.<br />

<strong>The</strong> student must, as a condition <strong>of</strong> a degree award, provide one paper copy and one<br />

electronic copy <strong>of</strong> the thesis or <strong>dissertation</strong> to Loyola/Notre Dame Library Inc.;<br />

completed signature pages in paper format are to accompany the paper thesis or<br />

<strong>dissertation</strong>.<br />

Loyola/Notre Dame Library Inc will not require express permission <strong>of</strong> the students to<br />

publish their theses or <strong>dissertation</strong>s electronically for the use <strong>of</strong> the Library's basic<br />

constituency: students, faculty, and staff <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Notre Dame and Loyola<br />

College, students, faculty, and staff <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> the Maryland Interlibrary<br />

Consortium, and walk-in patrons.<br />

Student Agreement:<br />

I hereby certify that, if appropriate, I have obtained and attached hereto a written<br />

permission statement from the owner(s) <strong>of</strong> each third party copyrighted matter to be<br />

included in my thesis, <strong>dissertation</strong>, or project report, allowing distribution as specified<br />

below. I certify that the version I submitted is the same as that approved by my<br />

advisory committee.<br />

I hereby grant to Loyola/Notre Dame Library Inc. the non-exclusive license to<br />

archive and make accessible, under the conditions specified below, my thesis,<br />

<strong>dissertation</strong>, or project report in whole or in part in all forms <strong>of</strong> media, now or<br />

hereafter known. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright <strong>of</strong> the thesis,<br />

<strong>dissertation</strong>, or project report. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as<br />

articles or books) all or part <strong>of</strong> this thesis, <strong>dissertation</strong>, or project report<br />

Please check the level <strong>of</strong> digital access that you grant the Loyola/Notre Dame Library Inc.<br />

Access by Library's basic constituency: students, faculty, and staff <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong><br />

Notre Dame and Loyola College, students, faculty, and staff <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> the Maryland<br />

Interlibrary Consortium, and walk-in patrons.<br />

World wide distribution via the Internet<br />

I hereby agree to the statement above and the indicated level <strong>of</strong> access to the digital reproduction <strong>of</strong><br />

my <strong>dissertation</strong>/thesis. I understand that I might want to discuss this with my <strong>dissertation</strong> advisor.

Running head: GRIEF SYMPTO<strong>MS</strong> IN WOMEN RELIGIOUS<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

<strong>The</strong> Impact <strong>of</strong> Social Support, Spirituality and Extraversion<br />

on Grief Symptoms in Women Religious:<br />

A Longitudinal Examination<br />

A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Graduate School <strong>of</strong> Loyola College in Partial Fulfillment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Requirements for the Degree <strong>of</strong><br />

Doctor <strong>of</strong> Psychology<br />

by<br />

Donna <strong>Kelley</strong>, <strong>IHM</strong>, M.S.<br />

2006

ABSTRACT<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

Research indicates that the bereavement process can be influenced by social<br />

support, spirituality and personality factors (Sanders, 1999). <strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> this study<br />

was to assess the impact that social support, spirituality and extraversion have on grief<br />

symptoms in Roman Catholic women religious. <strong>The</strong> participants in the present study<br />

totaled 82 active and contemplative women religious who had experienced the death <strong>of</strong> a<br />

family member or friend within seven months <strong>of</strong> the initial data collection. In addition,<br />

48 <strong>of</strong> the participants belonged to five active congregations and 34 <strong>of</strong> the participants<br />

belonged to 17 contemplative monasteries. <strong>The</strong> study was passive observational and<br />

longitudinal, with two times <strong>of</strong> measurement that were three months apart. <strong>The</strong> variables<br />

examined were type <strong>of</strong> religious life (active/contemplative), grief symptoms, social<br />

support, spirituality, and extraversion.<br />

Results indicate no significant association between social support and grief<br />

symptoms over time. Further results show that for women religious overall spirituality<br />

was not a significant predictor <strong>of</strong> grief over time.<br />

Multiple regressions were conducted separately for the two groups<br />

(active/contemplative). Results indicate that spirituality was a significant predictor <strong>of</strong><br />

time 2 residualized grief for the active group only. Moreover, for both groups, neither<br />

time 1 social support nor the interaction between spirituality and social support were<br />

predictive <strong>of</strong> grief over time. Additionally, no significant interaction<br />

between religious lifestyle and extraversion was found.<br />

i

Grief in Women Religious<br />

Multiple regression analyses found a significant main effect for religious<br />

lifestyles. Specifically, active women religious reported higher grief scores than did<br />

contemplatives. Post hoc analyses indicate significant differences in closeness to the<br />

deceased among the two groups.<br />

This study suggests that spirituality for bereaved active women religious has more<br />

<strong>of</strong> an impact on grief than it does for bereaved contemplatives. Furthermore, active<br />

women religious appear closer to the deceased and experience more grief than do<br />

contemplatives. Nevertheless, closeness to the deceased affects grief symptoms more for<br />

the contemplative group man it does for the active group. Differences in the active and<br />

contemplative lifestyles appear to play a role in the grief process. <strong>The</strong>refore, future<br />

research is needed to address these factors.<br />

ii

COMMITTEE IN CHARGE OF CANDIDACY:<br />

David Powers, Ph.D., Chairperson<br />

Carolyn Barry, Ph.D.<br />

Deborah Haskins, Ph.D.<br />

iii<br />

Grief in Women Religious

DEDICATION<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

To Bettyann, my sister, and Reverend Thomas <strong>Kelley</strong>, OSFS, USN, my uncle, the<br />

faith and love you shared are among my most treasured blessings. Thank you for<br />

enriching my life with your goodness. You are missed!<br />

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

<strong>The</strong> author would like to extend a special thank you to David Powers, Ph.D., my<br />

chairperson, for his help in completing this project. His continued support,<br />

encouragement, guidance and knowledge made this work possible and successful.<br />

Without his kindness and patience during the challenging times and his endless<br />

repetitions and explanations, this project would not have been completed. He has been a<br />

blessing during the past four years. It has been an honor to work with him and learn from<br />

him. In addition, the author would like to thank Carolyn Barry, Ph.D. for her interest,<br />

assistance and attention to detail throughout this study. She has been a gentle force and<br />

an invaluable consultant. <strong>The</strong> author would also like to express thanks to Deborah<br />

Haskins, Ph.D. for her support, encouragement, and assistance with this project. Her<br />

enthusiastic spirit and interest in this research was contagious and made working with her<br />

enjoyable.<br />

In addition, the author would like to thank the Sisters, Servants <strong>of</strong> the Immaculate<br />

Heart <strong>of</strong> Mary for their prayerful support and for making it possible to pursue this work.<br />

Furthermore, the author would like to thank her parents for their continued support,<br />

encouragement and belief in her. In a special way, the author would like to <strong>of</strong>fer thanks<br />

to her mother for her meticulous work in data entry. Her generous time commitment<br />

hastened a tedious process and made it memorable. Finally, the author would like to<br />

thank three special friends, Sisters Vicky, Barbara and Cindy for patiently traveling with<br />

her in pursuit <strong>of</strong> participants for this study. To each <strong>of</strong> you and the many others not<br />

mentioned by name, the author <strong>of</strong>fers prayers <strong>of</strong> gratitude.<br />

v

TABLE 1.<br />

TABLE 2.<br />

TABLE 3.<br />

TABLE 4.<br />

TABLE 5.<br />

TABLE 6.<br />

TABLE 7.<br />

TABLE 8.<br />

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Demographic Information for Participants<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Time Since Death and Relation to Deceased<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Descriptive Statistics for Variables <strong>of</strong> Interest<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

Intercorrelations between Time 1 and Time 2 Grief Symptoms and Time 1<br />

and Time 2 Social Support Satisfaction and Time 1 and Time 2<br />

Spirituality<br />

Stepwise Regression Analysis for Extraversion Variables predicting Grief<br />

Symptoms in Active and Contemplative Women Religious<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Descriptive Statistics for Lifestyle-Extraversion Interaction<br />

Page<br />

Stepwise Regression Analysis Among Active Women Religious for Variables<br />

Predicting Grief at Time 2<br />

Stepwise Regression Analysis Among Contemplative Women Religious for<br />

Variables Predicting Residualized Grief at Time 2<br />

vi<br />

19<br />

30<br />

32<br />

34<br />

35<br />

37<br />

38<br />

39

ABSTRACT<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

COMMITTEE IN CHARGE OF CANDIDACY<br />

DEDICATION<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

LIST OF TABLES<br />

CHAPTER I - Introduction<br />

Review <strong>of</strong> the Literature<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> Grief<br />

Social Support and Grief<br />

Personality and Grief<br />

Spirituality<br />

Application to Women Religious<br />

History <strong>of</strong> Religious Life<br />

Women Religious and Personality<br />

Women Religious and Grief<br />

Statement <strong>of</strong> the Problem<br />

Statement <strong>of</strong> Hypotheses<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

CHAPTER II-Method 18<br />

Participants 18<br />

vii<br />

Page<br />

i<br />

iii<br />

iv<br />

v<br />

vi<br />

1<br />

2<br />

2<br />

3<br />

6<br />

8<br />

11<br />

11<br />

13<br />

14<br />

16<br />

17

Grief in Women Religious<br />

Measures 18<br />

Procedures<br />

Texas Revised Inventory <strong>of</strong> Grief<br />

Social Support Questionnaire<br />

Revised NEO Personality Inventory - Extraversion Domain<br />

Spiritual Well-Being Scale<br />

Design and Analyses<br />

CHAPTER III-Results<br />

CHAPTER IV-Discussion<br />

Limitations<br />

Implications for Future Research<br />

REFERENCES<br />

APPENDIXES<br />

APPENDIX A. Human Subject Review Letter <strong>of</strong> Consent for Study<br />

APPENDIX B. Texas Revised Inventory <strong>of</strong> Grief<br />

APPENDIX C. Social Support Questionnaire<br />

APPENDIX D. Revised NEO Personality Inventory<br />

APPENDIX E. Spiritual Well-Being Scale<br />

APPENDIX F. Spiritual Well-Being Scale -Modified<br />

APPENDIX G. Cover Letter<br />

APPENDIX H. Demographic Questionnaire<br />

viii<br />

Page<br />

18<br />

21<br />

23<br />

24<br />

26<br />

29<br />

31<br />

41<br />

46<br />

47<br />

50<br />

59<br />

59<br />

61<br />

66<br />

73<br />

78<br />

80<br />

82<br />

84

APPENDIX I. Consent Form<br />

APPENDIX J. Contact Information<br />

APPENDIX K. Thank You Letter Time 1<br />

APPENDIX L. Thank You Letter Time 2<br />

ix<br />

Grief in Women Religious<br />

86<br />

88<br />

90<br />

92

CHAPTER 1<br />

Introduction<br />

Grief in Women Religious 1<br />

Research suggests that grief is a normal response to loss. Grief scholars have<br />

examined numerous populations; however, the present author has found no studies that<br />

concentrate on the loss experienced by Catholic women religious, individuals who<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ess the vows <strong>of</strong> chastity, obedience and poverty. In the Roman Catholic Church there<br />

are two forms <strong>of</strong> religious life for women: contemplative and active. Contemplative<br />

women religious choose to live these vows in solitude and prayer within the confines <strong>of</strong><br />

their monasteries. In contrast, active women religious choose a lifestyle that is<br />

committed to an apostolic work within the church. It is important for psychologists to<br />

understand this particular vocation because religious life may result in distinct treatment<br />

needs. Little is known, however, <strong>of</strong> how the death <strong>of</strong> a loved one affects women living<br />

these exceptional lifestyles. <strong>The</strong>refore, research in this area is needed in order to identify<br />

variables that impact the grief process in this population.<br />

<strong>The</strong> literature indicates that a variety <strong>of</strong> intrapersonal and interpersonal factors are<br />

related to grief. Two intrapersonal areas <strong>of</strong> special concern for this study were<br />

spirituality and the personality factor <strong>of</strong> extraversion. An interpersonal factor that this<br />

study examined was social support. <strong>The</strong>se issues were additionally addressed<br />

longitudinally in the context <strong>of</strong> Catholic women living the active and contemplative<br />

religious lifestyles.

Overview <strong>of</strong> Grief<br />

Review <strong>of</strong> the Literature<br />

Grief in Women Religious 2<br />

Research shows that grief following the death <strong>of</strong> a loved one is a normal reaction<br />

and one which varies across individuals (Malkinson, 2001). Strobe, Hansson, Stroebe,<br />

and Schut (2001) define grief as an emotional reaction to the loss <strong>of</strong> a loved one through<br />

death. <strong>The</strong> outward expression <strong>of</strong> grief is considered mourning (Ringdal, Jordhoy,<br />

Ringdal, & Kaasa, 2001). Grief and mourning are the outcome <strong>of</strong> bereavement, the<br />

situation <strong>of</strong> an individual having lost a loved one by death (Ringdal et al., 2001).<br />

Although grief is a normal response to the loss <strong>of</strong> a loved one, the length <strong>of</strong> the<br />

process may not be the same for everyone (Herkert, 2000). Some researchers suggest<br />

that grief reactions intensify immediately following the loss and decrease over time<br />

(Malkinson, 2001). However, other research indicates that for the duration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bereaved's life, feelings <strong>of</strong> grief commonly reoccur around significant dates associated<br />

with the deceased such as birthdays, holidays, or the anniversary <strong>of</strong> the death (Rosenblatt,<br />

1996). Walsh, King, Jones, Tookman, and Blizard (2002) found that bereaved people<br />

frequently reach a level <strong>of</strong> functioning that is close to typical for them between four to six<br />

months after the death. Ringdal et al. (2001) report a significant decline in grief<br />

symptoms from 1 month to 13 months after the death <strong>of</strong> a family member. In the first<br />

three months <strong>of</strong> the loss, there was a slight increase in grief reactions; however, it was not<br />

statistically significant. For these individuals, the major decrease in grief reactions<br />

occurred within three to sixth months after the loss.<br />

In contrast to these findings, Malkinson (2001) reports that normal grief work is<br />

not expected to be completed within a 12-month period. Results <strong>of</strong> a longitudinal study

Grief in Women Religious 3<br />

performed by Thompson, Gallagher-Thompson, Futterman, Gilewski, and Peterson<br />

(1991) also found that grief resolution may not be completed within the first year <strong>of</strong> the<br />

loss. This study found that grief can continue for 30 months after the death <strong>of</strong> a spouse.<br />

Furthermore, Parkes and Weiss (1983) suggest that depression may subside over the first<br />

12 months <strong>of</strong> bereavement, but distress surrounding loss issues continues for a number <strong>of</strong><br />

years.<br />

Several studies found that each loss is unique and that the bereaved lives the loss<br />

uniquely by getting in touch fully with their sorrow (Kenel, 1994; Solari-Twadell,<br />

Bunkers, Wang, & Snyder, 1995) and coping with their feelings (Cowan, 1983). DeVries<br />

(1997) reports that adjustment to the death <strong>of</strong> a loved one takes place on multiple levels.<br />

During this period <strong>of</strong> mourning, the bereaved person searches to find meaning in the<br />

death as well as a new self-meaning (Rosenblatt et al., 1991). Failure to admit the<br />

finality <strong>of</strong> the loss may leave the individual enveloped in depression and anger (Kenel,<br />

1994). <strong>The</strong> resolution <strong>of</strong> grief, however, can enhance an individual's personal richness<br />

and depth and lead to new inner strength (Solari-Twadell et al., 1995), which makes it<br />

possible for love and creativity to intensify (Laakso & Paunonen-Ilmonen, 2002).<br />

Research suggests that social support appears to have a positive effect on grief resolution<br />

and increases personal growth.<br />

Social Support and Grief<br />

Social support is a source <strong>of</strong> nurturance that can positively or negatively impact<br />

an individual's well-being (Laakso & Paunonen-Ilmonen, 2002). Through social support,<br />

individuals develop healthy coping strategies and come to view crises with new insight<br />

(Schaefer & Moos, 2001). By facilitating a clearer understanding <strong>of</strong> the stressful

Grief in Women Religious 4<br />

situation, social support reduces the effects <strong>of</strong> stress, supplies techniques to help make<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> a loss within the first several months <strong>of</strong> the death, and is a valuable way to cope<br />

with hardships (Krause, 1986; Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999).<br />

Social support functions as a coping resource that improves the individual's<br />

interpersonal support system and stimulates new interests, which may soothe the effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> the loss (Norris & Murrell, 1990; Sanders, 1999). Furthermore, social support serves<br />

as a diversion from depression, pushes the bereaved to face their grief (Rosenblatt, 1993),<br />

and can include emotional support and/or material support (Laakso & Paunonen-<br />

Ilmonen, 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999; Vachon & Stylianos, 1988).<br />

Emotional support involves family, friends and colleagues who provide the<br />

bereaved person with the space and opportunity to talk about their loss (Nolen-Hoeksema<br />

& Larson, 1999). <strong>The</strong>se individuals also supply emotional support through listening,<br />

touch, and expressions <strong>of</strong> sympathy and love (Kaunonen, Tarkka, Hautamaki, &<br />

Paunonen, 2000; Ringler & Hayden, 2000). This may be <strong>of</strong>fered through phone calls,<br />

cards, prayer or other visible manifestations <strong>of</strong> interest and concern (Webner, 1999).<br />

Moreover, the bereaved may find support from association with individuals who have<br />

experienced the same type <strong>of</strong> loss (Lehman et al, 1986; Rosenblatt, 1993). Herth (1990)<br />

found that the frequency <strong>of</strong> visits by family and friends were related positively to the<br />

level <strong>of</strong> grief resolution and level <strong>of</strong> hope in 75 bereaved spouses. Furthermore, other<br />

factors found to correlate significantly with grief resolution are situations where the<br />

bereaved feels connected to their social support network, engages in quality<br />

communication, and conveys feelings honestly (Vachon & Stylianos, 1988).

Grief in Women Religious 5<br />

Material or concrete support consists <strong>of</strong> deeds such as performing tasks or<br />

providing time that may alleviate the bereaved person's current difficulties (Kaunonen et<br />

al., 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). Aiken (2001) reports that valued forms <strong>of</strong><br />

material support, when provided with empathy, are <strong>of</strong>fering transportation or assistance<br />

with practical matters. This may include assisting with funeral arrangements, sorting<br />

through paper work, preparing meals or helping with household tasks (Nolen-Hoksema &<br />

Larson, 1999). It also may involve answering questions surrounding legal and financial<br />

issues (Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999).<br />

Several studies indicate that social support has a positive effect on bereavement.<br />

One such study by Ulmer, Range and Smith (1991) found that a high purpose in life was<br />

associated with an enhanced recovery from bereavement. <strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> this study<br />

suggest that this may be due to a more expanded social support system or a greater<br />

capacity to utilize social support in addition to a greater life satisfaction. W. Stroebe and<br />

M. Stroebe (1996) conducted a longitudinal study <strong>of</strong> 60 recently widowed and 60 married<br />

men and women. <strong>The</strong>ir results show that individuals with perceived high social support<br />

availability reported less depression and fewer somatic symptoms. In contrast,<br />

individuals with perceived low social support availability reported more depression and<br />

more somatic symptoms.<br />

Contrary to previous findings, research by Gamino and Sewell (1998) found that<br />

social support did not show a negative relationship with mourning. <strong>The</strong>se results indicate<br />

that what facilitates grief resolution is an involved coping style that actively intertwines<br />

the world, self and others. This implies that active behavior rather than passive behavior<br />

during bereavement may lead to a reduction in grief symptoms over time.

Grief in Women Religious 6<br />

Research also suggests that the quality <strong>of</strong> the social support rather than the<br />

quantity <strong>of</strong> social support has a positive impact on the grief process (Nolen-Hoeksema &<br />

Larson, 1999). In the case <strong>of</strong> bereaved women religious who live in community, the<br />

availability <strong>of</strong> social support may be <strong>of</strong> importance. This lifestyle provides a unique<br />

environment that includes living with women <strong>of</strong> various personalities, temperaments,<br />

ages and experiences. In addition, women religious also live closely with those who<br />

share similar goals and values. This may mean that grieving women religious will find a<br />

considerable amount <strong>of</strong> positive support from their community during a period <strong>of</strong><br />

bereavement. Alternatively, the close proximity in which women religious live with one<br />

another may make social support more <strong>of</strong> a challenge due to a lack <strong>of</strong> privacy and the<br />

conflicts that occur from daily life. Furthermore, since active women religious have<br />

more <strong>of</strong> an opportunity to engage in social relationships than do contemplative women<br />

religious, the effects <strong>of</strong> social support may be more evident among this group.<br />

Personality and Grief<br />

<strong>The</strong> intensity, quality and resolution <strong>of</strong> grief appear to be associated with the<br />

personality <strong>of</strong> the bereaved (Aiken, 2001). Furthermore, research indicates that<br />

personality characteristics (e.g. anxiety, conscientiousness, sociability), as measured<br />

through health and personality questionnaires, affect the ability to cope positively or<br />

negatively with grief (Sanders, 1999; Vachon, Rogers, et al., 1982). Results <strong>of</strong> a study<br />

performed by Meuser, Davies, and Marwit (1995) suggest that personality style can be a<br />

risk factor for complicated grief. Additionally, Vachon and Stylianos (1988) discuss<br />

personality factors such as anxiety, self-esteem and dependency that may determine the<br />

manner in which individuals attempt to elicit social support during bereavement. <strong>The</strong>se

Grief in Women Religious 7<br />

findings indicate that personality factors may impact the bereavement process. One<br />

component <strong>of</strong> personality that has not yet been well examined in regard to grief but may<br />

have an impact is extraversion/introversion.<br />

Research by McCrae and Costa (1987) has measured extraversion and<br />

introversion as opposite ends <strong>of</strong> a single continuum. According to these studies<br />

extraverted people are more sociable, friendly, talkative, high-spirited and demonstrative.<br />

On the other hand, the researchers describe introverts as reserved, independent, even<br />

paced and individuals who value their privacy. Morris (1979) claims that although<br />

extraverts are behaviorally vivacious, they are emotionally reserved. Conversely,<br />

introverts are behaviorally reserved, but they are aware <strong>of</strong> deep and various emotions.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, while introverts may not visibly express their emotions, they are more in touch<br />

with their emotions than are extraverts (Morris, 1979).<br />

Several studies that investigated various facets <strong>of</strong> life events included extraversion<br />

as one <strong>of</strong> the components. In one such study, Zautra, Finch, and Reich (1991) examined<br />

predictors <strong>of</strong> daily positive, negative, and ill-health events over time. Among the<br />

bereaved participants with unsupportive social networks, this study found a relation<br />

between extraversion and less physical problems but more undesirable events. In an<br />

additional study, Grace and O'Brien (2003) investigated the role that life events, presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a significant other, and personality factors have on depression. <strong>The</strong>ir findings show<br />

that <strong>of</strong> the 104 elderly participants, the individuals with multiple experiences <strong>of</strong><br />

bereavement also suffered from early-onset depression and received lower extraversion<br />

scores on a personality instrument than did the control group. Hotard, McFatter,<br />

McWhirter, and Stegall (1989) examined the interaction <strong>of</strong> extraversion, neuroticism and

Grief in Women Religious 8<br />

social support on subjective well-being. Results show that neurotic introverted<br />

individuals and introverted people with negative social support reported lower subjective<br />

well-being than either the extraverted or neurotic extraverted participants. According to<br />

the researchers, these findings may indicate that under adverse circumstances, introverted<br />

individuals may experience an increased sensitivity, which may be associated with their<br />

reports <strong>of</strong> lower subjective well-being. <strong>The</strong>se findings may suggest that during times <strong>of</strong><br />

bereavement, extraverted women religious may rely more on social support than do<br />

introverted women religious. In addition, the active religious life permits more<br />

interaction and communication with people than does the contemplative religious life.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, while both forms <strong>of</strong> religious life will include extraverted and introverted<br />

members, it would seem likely that more extraverted women would be found in the active<br />

religious life than in the contemplative religious life. Furthermore, during periods <strong>of</strong><br />

bereavement, the limitations imposed on social support by the structure <strong>of</strong> the<br />

contemplative lifestyle may hinder the grief process for extraverted contemplative<br />

women religious. Research also suggests that spirituality may influence bereavement.<br />

Spirituality<br />

Spirituality is multidimensional and defined in many different ways (Miller,<br />

1999). Paloutzian and Ellison (1991) suggest the term spiritual well-being to portray a<br />

clearer meaning <strong>of</strong> spirituality. As indicated by these researchers, when individuals refer<br />

to spirituality, they typically imply a relationship with God/ higher power or a<br />

contentment and purpose in life. Additionally, according to Miller (1999), spirituality is<br />

an attribute <strong>of</strong> a person and deals with individual subjective experiences. He further<br />

reports that spirituality does not necessarily involve religion. <strong>The</strong> author explains that

Grief in Women Religious 9<br />

spirituality also can focus on an indefinable substance that provides meaning in the<br />

individual's life. In recent years, bereavement scholars have attempted to integrate grief<br />

studies and spirituality by reflecting on clinical and/or individual experiences. Studies<br />

found that, for individuals who believe in God, grief may produce a spiritual crisis that<br />

leaves the bereaved depressed, helpless, and hopeless, and it also may raise faith<br />

questions that are incongruent with the individual's spiritual roots (Massey, 2000). This<br />

spiritual turning point reflects a rupture in the person's present relationship with God and<br />

consequently, the bereaved may experience loneliness and desolation (Massey, 2000).<br />

Consolation, however, may be obtained by sensing the presence <strong>of</strong> the deceased in a<br />

religious experience such as private prayer, ritual, or prayer services (Klass, 1993). On<br />

these occasions the mourners may feel God's presence which brings comfort and peace;<br />

however, many will likely still feel the sadness and emptiness associated with grief<br />

(Bullitt-Jonas, 1994).<br />

Balk's (1999) examination <strong>of</strong> case studies indicates that bereavement also affects<br />

spirituality by challenging innate beliefs about life. This may shake faith systems and<br />

lead to a period <strong>of</strong> inner turmoil as the bereaved searches for new meaning. In order to<br />

change the anguish into optimism and be transformed by God, the person must enter into<br />

the grief process, face the pain and make sense <strong>of</strong> the loss (Balk, 1999; Webner, 1999).<br />

In this way, spiritual change can occur and the individual may become compassionate<br />

(Balk, 1999; Chen, 1997). <strong>The</strong>refore, this research may suggest that during times <strong>of</strong> loss,<br />

grief may impact spirituality.<br />

Additional research indicates that spirituality is related to the bereavement<br />

process. Results <strong>of</strong> one qualitative study performed by Golsworthy and Coyle (1999)

Grief in Women Religious 10<br />

indicate that the experience <strong>of</strong> grief may appear to shake the faith <strong>of</strong> the bereaved<br />

because it is associated with questions and doubts. In spite <strong>of</strong> their confusion, the<br />

individuals in this study felt God's presence in their lives. <strong>The</strong>ir spirituality as evidenced<br />

by a sense <strong>of</strong> a personal and trusting link to God supported them through their grief.<br />

However, the bereaved also felt shame and self-criticism because they thought that their<br />

faith should help them cope more effectively with their grief.<br />

Furthermore, Marrone's (1999) examination <strong>of</strong> empirical research and clinical<br />

insights suggests that the loss <strong>of</strong> a loved one may challenge religious beliefs and raise<br />

questions about the meaning <strong>of</strong> life. As a result, the bereaved may experience a spiritual<br />

crisis; however, through active coping rather than passive coping this spiritual struggle<br />

may lead to the resolution <strong>of</strong> grief. <strong>The</strong>refore, spirituality may help the bereaved work<br />

through the mourning process (Marrone, 1999).<br />

During periods <strong>of</strong> severe pain or sadness, some individuals seek comfort from a<br />

religious or spiritual explanation for their loss (Sanders, 1999). Religious faith can<br />

cushion the detrimental consequences <strong>of</strong> a crisis and help the bereaved view the mundane<br />

with new insight and wisdom (Ellison, 1991). Research suggests that religious people<br />

tend to use more adaptive strategies and are less distressed than are nonreligious<br />

individuals (Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). Results <strong>of</strong> Fry's (2001) study <strong>of</strong> 188<br />

bereaved widows and widowers indicate that aspects <strong>of</strong> religious beliefs and spirituality<br />

are predictors <strong>of</strong> psychological well-being and coping with the death <strong>of</strong> a loved one.<br />

Scholars conceptualize the terms religious beliefs and spirituality as different<br />

constructs. Specifically, religious beliefs are innate convictions about how an individual<br />

relates to the sacred or divine and are <strong>of</strong>ten manifested outwardly (Miller, 1999).

Grief in Women Religious 11<br />

Spirituality, on the other hand, is a person's search to understand the meaning <strong>of</strong> life and<br />

to make life meaningful (Batten & Oltjenbruns, 1999). Spirituality pervades all aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> an individual's life (Golsworthy & Coyle, 2001) and involves forgiveness, compassion<br />

and feeling connected to a community (Mahoney & Graci, 1999). It is a perception <strong>of</strong><br />

existence that can be fostered and nurtured (Gamino, Sewell, & Easterling, 2000). While<br />

religious beliefs, people's convictions <strong>of</strong> transcendence and deity, appear to help the<br />

bereaved cope with their loss, the search for meaning surrounding loss may cause the<br />

individual to raise questions about these beliefs (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Miller,<br />

2000). <strong>The</strong>refore, spirituality, an individual's pursuit to find meaning in life, may impact<br />

the grief process.<br />

<strong>The</strong> relation between spirituality and bereavement is a particularly relevant issue<br />

to address in the context <strong>of</strong> grieving women religious. Spirituality is the core <strong>of</strong> women<br />

religious' lives and encompasses all aspects <strong>of</strong> their existence. Thus, spirituality should<br />

be a major source <strong>of</strong> strength and comfort for bereaved women religious. For<br />

contemplative women religious whose primary focus is a life dedicated to prayer and<br />

whose main social support comes from their community, spirituality may have more <strong>of</strong><br />

an initial impact on the grief process than it will have on the grief process for active<br />

women religious who have more <strong>of</strong> a social support network. Little research, however, is<br />

available to address these issues.<br />

Application to Women Religious<br />

History <strong>of</strong> religious life. Religious life in the Roman Catholic Church has been in<br />

existence for nearly 2000 years (Schneiders, 2001). During the second century, the<br />

tradition <strong>of</strong> women living as consecrated virgins began, and over time this practice was

Grief in Women Religious 12<br />

replaced by the vows <strong>of</strong> chastity, poverty and obedience (Cita-Malard, 1964). In the fifth<br />

century, the first women monasteries were established by Scholastica under the guidance<br />

<strong>of</strong> her brother Benedict. In these monasteries, the women followed the Benedictine rule<br />

that structured how they lived, worked, and prayed together. In 1283, as a safeguard for<br />

nuns against the barbarian invasion, Pope Boniface VIII erected enclosure. It was not<br />

until the 16 th century, however, that the Council <strong>of</strong> Trent enforced the rules <strong>of</strong> solemn<br />

vows and enclosure on all women who live in community (Cita-Malard, 1964). <strong>The</strong><br />

institution <strong>of</strong> contemplative religious life as it is lived out in the Roman Catholic Church<br />

began at this time. Contemplative women religious not only pr<strong>of</strong>ess the vows <strong>of</strong> chastity,<br />

poverty, and obedience they also choose to live a life <strong>of</strong> solitude and prayer within the<br />

confines <strong>of</strong> their monasteries.<br />

Active religious life also came into existence in the 16 th century as a result <strong>of</strong> the<br />

needs <strong>of</strong> the times (Cita-Malard, 1964). Active women religious also pr<strong>of</strong>ess the vows <strong>of</strong><br />

chastity, poverty, and obedience as well as commit themselves to an apostolic work in the<br />

church. At this time, women religious were permitted to assume a less rigid rule <strong>of</strong><br />

enclosure and work as teachers or in hospitals (Cita-Malard, 1964). Throughout the<br />

centuries, religious congregations were established to meet the needs <strong>of</strong> the times and <strong>of</strong><br />

the Catholic Church. Typically, a congregation was established by one or two founders<br />

who decided on the purpose, way <strong>of</strong> life, and who wrote a rule for the group.<br />

Women religious are called to serve the Church within a community, and they<br />

enter religious life to live out the gospel message according to the specific spirit and<br />

values <strong>of</strong> a congregation (Donavan, 1989). <strong>The</strong> two basic forms <strong>of</strong> religious life for<br />

women are the active and the contemplative lifestyles. Schneiders (2000) explains that

Grief in Women Religious 13<br />

contemplatives distinguish themselves by prayer which is the unique visible expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> their lifestyle. Contemplative women religious live a life <strong>of</strong> solitude, prayer and<br />

withdrawal from the world. Rarely will events or circumstances interrupt the structure <strong>of</strong><br />

community exercises or common prayer. <strong>The</strong>se women choose to spend their life within<br />

one monastery and usually are not transferred to another house.<br />

In contrast, ministry is the distinct characteristic <strong>of</strong> the active religious lifestyle<br />

(Schneider, 2000). In this type <strong>of</strong> life, women religious strive to balance a life <strong>of</strong> prayer<br />

(private and common), commitment to their congregation, and a job related to the service<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Catholic Church. Active women religious choose to serve God's people where<br />

they are most needed, and consequently, their ministry may necessitate the need for them<br />

to move to new geographical areas.<br />

Women religious and personality. Although little research can be found on the<br />

personality types <strong>of</strong> women who seek admission into religious life, one may surmise that<br />

since active religious life provides opportunities to develop numerous interpersonal<br />

relationships more extraverted women will seek entrance into these congregations than<br />

will introverted women. Conversely, more introverted women would be expected to seek<br />

admittance into contemplative religious congregations as this lifestyle lends itself to<br />

solitude and little contact with strangers or other people in general. Interestingly,<br />

Donavan (1989) suggests that naive women who seek interpersonal relationships and<br />

protection may look for these things in a contemplative congregation. <strong>The</strong> majority <strong>of</strong><br />

religious congregations, however, utilize psychological assessments to evaluate applicant<br />

suitability for religious life (Batsis, 1993).

Grief in Women Religious 14<br />

Women religious and grief. Grief is a life crisis and crises can impact social<br />

relationships and initiate spiritual change (Balk, 1999). Women religious are not<br />

excluded from this grief process. When these women lose a loved one, their grief is<br />

unique to them as individuals and may be influenced by their religious life. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

women choose to live a countercultural lifestyle. As a result, the potency <strong>of</strong> their grief<br />

may go unnoticed or be misconstrued because people do not understand their way <strong>of</strong> life<br />

or the depth <strong>of</strong> their love for others. Bowlby (1980) discusses several factors that may<br />

predict complicated grief including unresolved previous losses, the inability to develop<br />

meaningful relationships, living alone, unhelpful social interaction, persistent anger, self-<br />

reproach, and depression. In addition, Sanders (1999) cautions that postponing grief or<br />

acting as though the loss did not occur may be symptoms <strong>of</strong> abnormal grief. <strong>The</strong>se issues<br />

may be <strong>of</strong> particular relevance for bereaved women religious because <strong>of</strong> their highly<br />

spiritual life and their bond with members <strong>of</strong> their congregation.<br />

Furthermore, Doka (1987) indicates that grief may be intensified in nontraditional<br />

relationships and add confusion to the bereavement process. This may be especially true<br />

for contemplative religious whose lifestyle may not permit them to leave their enclosure<br />

to care for a family member or visit a dying friend. Consequently, the bereaved women<br />

religious may feel isolated, lonely and depressed. As research suggests (Kaltreider,<br />

Becker, & Horowitz, 1984; Parkes, 1998), women may be more sensitive than men to the<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> a parent, which may lead to psychological problems; women religious should be<br />

no exception. <strong>The</strong> death <strong>of</strong> parents may leave a woman religious with a feeling <strong>of</strong><br />

"homelessness" and a sibling's death may break a tie to a family unit. Without a family<br />

<strong>of</strong> her own, the bond with her nuclear family may be intense and the finality <strong>of</strong> the loss

Grief in Women Religious 15<br />

may be tremendous. <strong>The</strong> grief <strong>of</strong> a woman religious also may be complicated because<br />

her life <strong>of</strong> selfless service may inhibit her from admitting or expressing the pain and<br />

emptiness caused by death.<br />

For active and contemplative women religious who live in community the<br />

availability <strong>of</strong> positive social support should ease the grieving process. <strong>The</strong>se women<br />

have available to them community members who are willing to listen, to help in practical<br />

matters and to share with individuals who have experienced similar losses. Ideally,<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the woman religious' local convent will support her through the grieving<br />

process with their physical and spiritual presence. Moreover, active women religious<br />

have the liberty to engage in social relationships with other religious outside <strong>of</strong> their local<br />

community as well as lay friends and colleagues. <strong>The</strong>se relationships may provide active<br />

women religious with additional support during the bereavement process.<br />

<strong>The</strong> grief process also may be affected by the woman religious' personality. An<br />

extraverted grieving woman religious may tend to seek social support outside <strong>of</strong> her local<br />

house, look for distractions from her pain, and express more visible grieving emotions.<br />

Contrary to this, an introverted woman religious may be more satisfied with the social<br />

support received from her local community, be more in touch with her emotions, be less<br />

expressive <strong>of</strong> these emotions, and seek more time alone than an extraverted woman<br />

religious.<br />

A woman religious would be expected to turn to God and her faith for comfort<br />

and support during times <strong>of</strong> grief. Religious beliefs may bring a sense <strong>of</strong> solace that her<br />

loved one is in heaven and that one day she will be reunited with the deceased. <strong>The</strong><br />

support <strong>of</strong> the funeral liturgy, prayer services and rituals that envelop the days following

Grief in Women Religious 16<br />

a death may be a source <strong>of</strong> strength for the bereaved woman religious. This does not<br />

mean, however, that the woman religious will not feel the pain associated with the loss <strong>of</strong><br />

the loved one. It does mean that her faith may influence this grief process in a significant<br />

manner. For contemplative women religious whose life is dedicated to prayer and<br />

solitude, the resolution <strong>of</strong> grief may primarily involve a focus on spirituality. This may<br />

be a natural consequence <strong>of</strong> enclosure and limited social contacts. Conversely, for active<br />

women religious who are immersed in an apostolic ministry, the resolution <strong>of</strong> grief may<br />

initially focus on social support. <strong>The</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> social support from a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

sources may make this a feasible preference. However, over time the active women<br />

religious may turn more towards their faith and relationship with God for comfort. This<br />

refocus on spirituality may consequently flow from their primary commitment to God.<br />

Furthermore, research suggests that spirituality may not only help the bereaved work<br />

through the grief process, but also lead to a stronger interior life (Marrone, 1999; Massey,<br />

2000).<br />

Statement <strong>of</strong> the Problem<br />

Grief is an inescapable fact <strong>of</strong> life. <strong>The</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> the grieving process can<br />

be seen both in research, self-help literature and support groups available to the bereaved.<br />

Research on grief suggests that bereavement is an intensely emotional period that lasts<br />

for an indeterminate length <strong>of</strong> time. Women religious experience many losses that affect<br />

their life in a pr<strong>of</strong>ound way. Among these losses are the deaths <strong>of</strong> parents, siblings,<br />

relatives, community members and intimate friends. Little research, however, can be<br />

found that addresses the issues <strong>of</strong> loss within a religious community. Women religious

Grief in Women Religious 17<br />

attempt to deal with these outcomes while they continue to serve God's people and live in<br />

community.<br />

Present research suggests that social support and spirituality are important factors<br />

in bringing the grieving process to a healthy resolution. Research also indicates that<br />

personality factors may affect the grief process. <strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to<br />

determine the impact that social support, spirituality and the personality factor <strong>of</strong><br />

extraversion have on grief symptoms in active and contemplative women religious. <strong>The</strong><br />

relations among these variables were examined over a 3 month time period.<br />

Statement <strong>of</strong> Hypotheses<br />

1. <strong>The</strong>re is a relation between social support and grief symptoms such that the social<br />

support <strong>of</strong> women religious is related negatively to grief symptoms over time.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong>re is a relation between spirituality and grief symptoms such that the<br />

spirituality <strong>of</strong> women religious is related negatively to grief symptoms over time.<br />

3. <strong>The</strong>re is a significant interaction between women religious lifestyles and<br />

personality factors in relation to grief symptoms, such that extraversion is related<br />

negatively to grief symptoms over time in active women religious and related<br />

positively to grief symptoms in contemplative women religious over time.<br />

4. <strong>The</strong>re is a difference between women religious lifestyles in relative contribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> time 1 spirituality and social support in predicting time 2 grief symptoms, such<br />

that social support and spirituality will be more predictive <strong>of</strong> grief among active<br />

women religious and spirituality alone will be predictive <strong>of</strong> grief among<br />

contemplative women religious.

Participants<br />

Chapter II<br />

Method<br />

Grief in Women Religious 18<br />

<strong>The</strong> participants in this study were 82 Roman Catholic women religious<br />

who had experienced the death <strong>of</strong> a family member or friend within the past seven<br />

months. In addition, 58% (n = 48) <strong>of</strong> the participants belonged to five active<br />

congregations and 42% (n = 34) were members <strong>of</strong> 17 contemplative monasteries.<br />

Furthermore, the participants were drawn from the New England, Mid-Atlantic,<br />

Southern, and Midwestern states. <strong>The</strong> entire population spoke English and 89% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

participants describe themselves as White/European American. In this study, the median<br />

age for the active participants was 63 and the median age for the contemplative<br />

participants was 61. This is comparable to the 1999 statistics for women religious in the<br />

United States which reports a median age <strong>of</strong> 68 for active women religious and a median<br />

age <strong>of</strong> 65 for contemplative women religious (Froehle et al., 2000).<br />

Moreover, the participants represented a range <strong>of</strong> educational levels. See Table 1<br />

for summary <strong>of</strong> demographic information. Approval to use human subjects was obtained<br />

from the Human Subject committee <strong>of</strong> Loyola College in Maryland (see Appendix A).<br />

Measures<br />

Grief. Symptoms <strong>of</strong> grief were measured with Part II titled, "Present Feelings,"<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Texas Revised Inventory <strong>of</strong> Grief (TRIG; Faschingbauer, Zisook, & De Vaul,<br />

1987; see Appendix B). Faschingbauer et al. designed this measure to evaluate grief "as<br />

a present emotion <strong>of</strong> longing, as an adjustment to a past life event, as a medical<br />

psychology outcome, and as a personal experience" (1987, p. 111). <strong>The</strong> items <strong>of</strong> this

Table 1<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Demographic Information for Participants<br />

Age<br />

Active<br />

Contemplative<br />

Years in Lifestyle<br />

Active<br />

Contemplative<br />

Ethnicity<br />

White/European<br />

American<br />

Native American<br />

Black/Latino<br />

White/Native<br />

American<br />

Education<br />

H.S. Diploma<br />

Bachelors<br />

Masters<br />

Doctoral<br />

Other/Missing<br />

Minimum<br />

40<br />

46<br />

40<br />

.75<br />

22<br />

.75<br />

Maximum<br />

81<br />

M<br />

62.79<br />

Grief in Women Religious 19<br />

SD<br />

9.98<br />

N<br />

82<br />

%<br />

81 63.73 9.32 48 58.5<br />

79<br />

63<br />

61.47<br />

42.03<br />

10.85<br />

12.73<br />

34<br />

78<br />

63 44.13 10.32 46<br />

58<br />

39.01<br />

15.22<br />

32<br />

82<br />

73<br />

7<br />

41.5<br />

89<br />

8.5<br />

1 1.2<br />

1<br />

82<br />

12<br />

1.2<br />

14.6<br />

12 14.6<br />

49<br />

59.8<br />

2 2.4<br />

Note. Other/Missing = some college credits; three participants did not report number <strong>of</strong><br />

years in religious life.<br />

7<br />

8.5

Grief in Women Religious 20<br />

measure were developed by Faschingbauer and colleagues based on their clinical<br />

experience as well as literature for normal and atypical grief (Stroebe et al., 2001).<br />

<strong>The</strong> TRIG consists <strong>of</strong> 26 items that assess feelings and actions surrounding the death <strong>of</strong> a<br />

loved one. <strong>The</strong> introductory section <strong>of</strong> the TRIG assesses the individual's relationship<br />

with the deceased, perceived closeness with the deceased, and length <strong>of</strong> time since the<br />

death occurred. This inventory also consists <strong>of</strong> two primary scales, which are composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> simple statements. Part I, titled "Past Behavior," consists <strong>of</strong> eight items that assess<br />

behavior occurring shortly after the death (e.g., "I found it hard to sleep after this person<br />

died"). <strong>The</strong> participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "Completely<br />

True" to "Completely False." On this section, the items are reverse scored and the scores<br />

range from 8 to 40 (Longman, 1993).<br />

Part II, titled "Present Feelings," consists <strong>of</strong> 13 items that assess feelings at the<br />

time <strong>of</strong> the data collection (e.g., "I still get upset when I think about the person who<br />

died;" Ginzburg, Geron, & Solomon, 2002). Part II is the primary measure used to assess<br />

change in grief symptoms over a period <strong>of</strong> time (Stroebe et al., 2001). On this scale, the<br />

participants also respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "Completely True" to<br />

"Completely False," such that the scores on Part II can range from 13 to 65 (Longman,<br />

1993). In addition, the items are reverse scored. For this study, the mean<br />

score for Part II used to assess grief symptoms over time.<br />

Part III, titled "Related Facts," consists <strong>of</strong> five basic statements that assess<br />

information associated with the death <strong>of</strong> the individual (Longman, 1993). For this<br />

section, the participants respond either true or false. <strong>The</strong> TRIG concludes with an open-<br />

ended question that asks participants to add other thoughts or feelings. For the purposes

Grief in Women Religious 21<br />

<strong>of</strong> this study, no specific hypothesis will utilize the qualitative data gathered from the<br />

TRIG.<br />

Research shows the TRIG to have a moderate level <strong>of</strong> reliability with coefficient<br />

alphas <strong>of</strong> .77 for Part I and .86 for Part II (Stroebe, Stroebe, & Hansson, 1993).<br />

Furthermore, in a study <strong>of</strong> 260 adults, the coefficient alpha for Part II was .77<br />

(Faschingbauer et al., 1987). In a longitudinal study performed by Longman (1993),<br />

grief symptoms were assessed in male and female adults at three months to two years<br />

postloss and than three months later. <strong>The</strong> Cronbach's alpha in that study ranged from .78<br />

to .93 for different sections <strong>of</strong> the TRIG at different times <strong>of</strong> measurement. In the present<br />

study, for Part II, the coefficient alphas for time 1 and time 2 were .85 and .83.<br />

Some modifications were made on the TRIG to reflect the present study's<br />

population and time frame. Specifically, in the inventory items, husband and wife were<br />

removed and time since the person died was revised to range from ''within the past<br />

month" to "within the past 4 to 7 months," Furthermore, in Part III, on item four, "each<br />

year" was changed to read "each month." However, no items in Part II were altered,<br />

which is the primary scale used to assess changes in symptoms <strong>of</strong> grief and was the only<br />

section used in this study.<br />

Social support. Social Support was measured using the Social Support<br />

Questionnaire (SSQ; Sarason, Levine, Basham, & Sarason, 1983). <strong>The</strong> SSQ measures<br />

the participant's availability for and his or her satisfaction with social support (see<br />

Appendix C). Sarason et al. (1983) derived their definition <strong>of</strong> social support from<br />

Bowlby's <strong>The</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> Attachment, basing it on the accessibility <strong>of</strong> individuals on whom<br />

they can depend, who care for them and who support them. <strong>The</strong> SSQ consists <strong>of</strong> 27

Grief in Women Religious 22<br />

items that ask the subject to list who they can turn to in particular situations and then to<br />

rate their satisfaction with the support that they receive from these people on a 6-point<br />

Likert scale ranging from "very satisfied" to "very dissatisfied" (Heitzmann & Kaplan,<br />

1988). <strong>The</strong> items are reverse scored. <strong>The</strong> SSQ is scored by first adding the total number<br />

<strong>of</strong> people listed (maximum number is 243). This total is the SSQ Number Score (SSQN;<br />

Sarason et al., 1983). <strong>The</strong> Total Satisfaction score for all 27 items (Max = 162) is also<br />

computed. This score is the SSQ Satisfaction score (SSQS; Bowling, 1997). By dividing<br />

the sum <strong>of</strong> the SSQN and SSQS scores by 27, the total number <strong>of</strong> items, the overall N<br />

and S scores are obtained (Sarason et al., 1983).<br />

Reliability for the SSQ in a college student sample was assessed by Sarason et al.<br />

(1983). Results show an alpha coefficient <strong>of</strong> .97 and an alpha coefficient for satisfaction<br />

scores <strong>of</strong> .94. Similarly, in the present study, the coefficient alphas for time 1 and time 2<br />

were .94 and .95 respectively.<br />

Construct validity for the SSQ was tested in a study <strong>of</strong> 227 male and female<br />

college students who were given the SSQ, the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List<br />

(MAACL), and the Lack <strong>of</strong> Protection Scale (LP; Heitzmann & Kaplan, 1988).<br />

Significant negative correlations <strong>of</strong> -.22 and -.43 were reported between the SSQ-N and<br />

the SSQ-S and the MAACL that assesses emotional discomfort. Additionally, a negative<br />

correlation (-.22 and -.32) was found between the LP and the SSQ. A subsample <strong>of</strong> 28<br />

men and 38 women from this study was administered Extraversion and Neuroticism<br />

scales. <strong>The</strong> Extraversion measure for women was correlated positively (r = .35) with the<br />

SSQ-N, and was correlated negatively (r = -.37) with the Neuroticism scale for women.

Grief in Women Religious 23<br />

For the purpose <strong>of</strong> the present study, three items that did not apply to this<br />

population were eliminated. Specifically, items 4, 10, and 15 were not included in the<br />

participants' total scores as they addressed issues not related to the religious lifestyle such<br />

as marriage.<br />

Personality. Extraversion was measured using the Revised NEO Personality<br />

Inventory (NEO PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992). <strong>The</strong> NEO PI-R measures five major<br />

dimensions <strong>of</strong> personality: Neuroticism, Extroversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and<br />

Conscientiousness. <strong>The</strong> self-report form <strong>of</strong> the NEO PI-R consists <strong>of</strong> 240 items.<br />

Participants are asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly<br />

disagree" to "strongly agree." Each <strong>of</strong> the five domains contains six subscales that<br />

measure a variety <strong>of</strong> facets <strong>of</strong> that specific domain. For the purpose <strong>of</strong> this study, only<br />

the 48 items from Form S that measure extraversion was used (see Appendix D).<br />

Numerous studies have been performed to evaluate the reliability <strong>of</strong> the NEO PI-<br />

R. Two research designs that include coefficient alphas for the Extraversion scale will be<br />

reviewed. Costa, McCrae, and Dye (1991) and Costa and McCrae (1992) report internal<br />

consistencies for the individual facet scales <strong>of</strong> the NEO PI-R. In a study <strong>of</strong> 1,539<br />

participants, the coefficient alphas for the individual facet scales ranged from .56 to .81.<br />

Additionally, on the 48-item Extraversion scale the coefficient alphas ranged from .63 to<br />

.77.<br />

McCrae and Costa (1983) report retest reliability for the NEO PI-R in a study <strong>of</strong><br />

31 men and women. <strong>The</strong> values for the facet scales ranged from .66 to .92. In this same<br />

study, the reliability value for the Extraversion scale was .91. Furthermore, in a sample<br />

<strong>of</strong> 208 college students, the test-retest reliability coefficient for Extraversion was reported

Grief in Women Religious 24<br />

as .79 (p < .001; Costa & McCrae, 1992). In the present study, a coefficient alpha <strong>of</strong> .91<br />

was found for the NEO-E.<br />

Spirituality. Spirituality was measured using the Spiritual Well-Being Scale<br />

(SWB; Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982). <strong>The</strong> SWB scale gives a global assessment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

subjective spiritual quality <strong>of</strong> life (see Appendix E). Paloutzian and Ellison (1991) state<br />

that the term "spiritual well-being" reflects people's meaning <strong>of</strong> spirituality as "either<br />

their relationship with God or what they understand to be their spiritual being, or their<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> satisfaction with life or purpose in life" (p.2). <strong>The</strong> SWB total score presents a<br />

general measure <strong>of</strong> an individual's spiritual well-being. Additionally, the SWB contains<br />

two subscales. <strong>The</strong> Religious Well-Being score (RWB) provides an assessment <strong>of</strong> an<br />

individual's relationship with God and the individual's perceived satisfaction with God.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Existential Well-Being (EWB) score assesses an individual's satisfaction with and<br />

purpose in life (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1991).<br />

<strong>The</strong> SWB is a 20-item self-administered instrument Responses are given on a 6-<br />

point Likert scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree." RWB is assessed<br />

by the ten even-numbered statements that contain the word "God" and the ten remaining<br />

odd numbered items assess EWB (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1991). In an attempt to control<br />

for response bias, about half <strong>of</strong> the items are worded in a negative fashion. <strong>The</strong><br />

statements are scored from 1 to 6. For positive items, a higher number represents greater<br />

well-being, and the negatively worded items are reverse scored. <strong>The</strong> sum <strong>of</strong> all 20 items<br />

assesses overall spiritual well-being (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1991).<br />

Bufford, Paloutzian, and Ellison (1991) found high reliability for the SWB in four<br />

test-retest studies. <strong>The</strong> reliability coefficients ranged from .88 to .98 for RWB, .73 to .98

Grief in Women Religious 25<br />

for EWB, and .82 to .99 for SWB. In addition, the index <strong>of</strong> internal consistency<br />

coefficient alpha, also showed high reliability across seven samples. <strong>The</strong>se results ranged<br />

from .82 to .92 for RWB, .78 to .86 for EWB, and .89 to .94 for SWB. Similarly, in the<br />

present study, the coefficient alphas for the SWB at time 1 and time 2 were .92 and .90<br />

respectively.<br />

Additionally, Bufford et al. (1991) found that the SWB is a valid gauge for overall<br />

well-being. <strong>The</strong> three scales are correlated positively with purpose in life and are<br />

correlated negatively with loneliness (Ellison, 1983). A ceiling effect has been reported<br />

by the authors in some religious samples (Hill & Hood, 1999). This measure, however, is<br />

sensitive at the low end and research suggests that it may be a useful instrument to assess<br />

those experiencing spiritual distress or lack <strong>of</strong> well-being (Hill & Hood, 1999).<br />

A pilot study was performed in March 2003 to determine if the SWB scale would<br />

be an effective measure to use with women religious. Twenty members <strong>of</strong> two women<br />

religious congregations living in Maryland and Pennsylvania took part in this study.<br />

None <strong>of</strong> these women participated in this present study. It was hypothesized that scores<br />

on the modified version <strong>of</strong> the scale (see Appendix E) would show significantly more<br />

variability than would scores on the original version <strong>of</strong> the scale. <strong>The</strong> modified scale<br />

ranged from 0 to 100 instead <strong>of</strong> 0 to 5. <strong>The</strong> reason, for the modification, was concern<br />

that the range <strong>of</strong> 0 to 5 would not show enough variability in such a highly spiritual<br />

group. Findings show a mean <strong>of</strong> 1841.90 and a standard deviation <strong>of</strong> 143.61 for the<br />

modified version. For the original version, a mean <strong>of</strong> 108.35 and standard deviation <strong>of</strong><br />

10.69 was found. <strong>The</strong> maximum score on the original scale is 120, and the maximum<br />

score on the modified scale was 2000. Three women religious reported the maximum

Grief in Women Religious 26<br />

score on both the original and modified scales. <strong>The</strong>re was no ceiling effect with either<br />

the original measure or the modified measure. This indicates no significant difference<br />

between the two versions <strong>of</strong> the scales; therefore, it was decided the original scale would<br />

be used. <strong>The</strong>se results are similar to those <strong>of</strong> O'Kane (19%) who used the original SWB<br />

in a study <strong>of</strong> women religious. Furthermore, at time 1 and time 2, this present study<br />

found significant correlations between the TRIG (r = .80, p < .05), the SSQ (r = .79, p <<br />

.05), and the SWB (r = .70, p < .05).<br />

Procedure<br />

Data collection began subsequent to receiving approval from the author's<br />

<strong>dissertation</strong> committee and the Human Subject committee <strong>of</strong> Loyola College in<br />

Maryland. A second time <strong>of</strong> measurement occurred three months after the first data<br />

collection. A list <strong>of</strong> 12 active women religious congregations and 16 contemplative<br />

monasteries <strong>of</strong> women were obtained from the Official Catholic Directory (2003). All<br />

congregations and monasteries obtained from this source were located within the eastern<br />

region <strong>of</strong> the United States. General leadership members <strong>of</strong> nine active congregations<br />

were contacted by phone and a personal interview date was requested. One individual in<br />

lieu <strong>of</strong> a personal interview suggested that e-mail messages be sent to the 17 presidents <strong>of</strong><br />

the congregation situated throughout the United States. Furthermore, due to scheduling<br />

conflicts, two other persons requested that a letter be sent explaining the procedures for<br />

this study. Phone messages were left with general leadership members <strong>of</strong> three other<br />

active congregations, but no response was obtained. Several e-mail messages were sent<br />

to one <strong>of</strong> the individuals, but a request for a meeting was not obtained. <strong>The</strong>refore, a total<br />

<strong>of</strong> 12 active congregations were contacted.

Grief in Women Religious 27<br />

<strong>The</strong> superior and/or contact person <strong>of</strong> 16 contemplative communities were<br />

contacted by phone, mail, e-mail or through personal interviews. Due to the small<br />

number <strong>of</strong> participants, names <strong>of</strong> four additional monasteries were verbally given to the<br />

researcher by colleagues and these monasteries were either visited or contacted by phone.<br />

Furthermore, 58 monasteries, throughout the United States and Ireland, were located on<br />

the internet and they were contacted by e-mail. <strong>The</strong>refore, 79 contemplative monasteries<br />

were contacted and 48 <strong>of</strong> them responded. <strong>The</strong>se monasteries were located across the<br />

United States.<br />

<strong>The</strong> names and addresses <strong>of</strong> women religious who had lost a parent, sibling or<br />

close friend within the last three months were either mailed to the researcher or the<br />

women were personally contacted by their leadership personnel to assess their<br />

willingness to participate in this study. Subsequently, the names and contact information<br />

<strong>of</strong> the women willing to participate were either forwarded to the researcher or the<br />

participant personally contacted the researcher by e-mail or phone.<br />

A packet <strong>of</strong> materials was mailed to the active and contemplative women<br />

religious as distance made it unfeasible to visit each convent. For each eligible<br />

contemplative woman religious who resided in the monastery that was visited, a packet <strong>of</strong><br />

materials was left at the monastery for her. Before the packets were mailed or<br />

distributed, identification numbers for coding purposes were placed on each <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

<strong>The</strong> packets included a cover letter, a consent form, a demographic questionnaire, the<br />

Texas Revised Inventory <strong>of</strong> Grief (Faschingbauer, 1981; see Appendix B), the Social<br />

Support Questionnaire (Sarason et al., 1983; see Appendix C), the NEO PI-E (Costa &<br />

McCrae, 1992; see Appendix D) and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Paloutzian &

Grief in Women Religious 28<br />

Ellison, 1982; see Appendix E). <strong>The</strong> measures were arranged in a counterbalanced<br />

order.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cover letter described the purpose and procedure <strong>of</strong> the study (see Appendix<br />

F). It also provided information on confidentiality, voluntary participation, risks and<br />

benefits involved in participation, and the person to contact if a question arose. <strong>The</strong><br />

cover letter also indicated that a doctoral psychology student at Loyola College in<br />

Maryland conducted the study. Additionally, the cover letter informed the participants<br />

that there was a 3-month follow-up study to assess the impact <strong>of</strong> social support and<br />

spirituality on the grief process in women religious. <strong>The</strong> demographic questionnaire<br />

included questions regarding age, years in religious life, level <strong>of</strong> education, ethnicity, and<br />

type <strong>of</strong> work (see Appendix G). Voluntary consent to participate in the study was shown<br />

by returning the consent form (see Appendix H).<br />

In order to perform the follow-up study and to maintain confidentiality,<br />

participants were asked to provide the researcher with contact information on a separate<br />

sheet <strong>of</strong> paper (see Appendix I). <strong>The</strong> number <strong>of</strong> packets distributed totaled 114 (Active =<br />

62; Contemplative = 52), and the number <strong>of</strong> responses to time 1 totaled 93 (Active = 53;<br />

Contemplative = 40). Upon return <strong>of</strong> the questionnaires, thank you letters were mailed to<br />

each participant with a reminder <strong>of</strong> the follow-up study (see Appendix J). Moreover,<br />

postcard or e-mail reminders were mailed to those who did not respond. Three months<br />