41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

41119_Niro jubilaeumsbog_blok_uk - GEA Niro

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The challenges of drying milk<br />

Born on a Friday the 13th and fled from the communist regime<br />

with his family on October 13, 1968 at 1300 hours was perhaps<br />

not the most optimistic basis for a great career as head of <strong>Niro</strong>’s<br />

milk development department. But Jan Pisecký from the Czech<br />

Republic had other plans.<br />

With a background as a chemical engineer from the Technical<br />

University of Prague and a Ph.D. degree thereafter, Jan Pisecký<br />

became head of the Czech Dairy Research Institute – a position<br />

which for political reasons was intolerable to him. Until<br />

1968 there had not been many development projects at <strong>Niro</strong><br />

for milk powder spray plants, but after Jan Piceský was<br />

hired, things started to happen.<br />

The first challenge for <strong>Niro</strong> was to make a whole milk powder,<br />

which contains milk fat, soluble in cold water.<br />

Some of the milk fat is forced out onto the surface of the<br />

powder particles, which makes the particles water-repellent<br />

– especially when the water is cold. One of the requirements<br />

was that only “natural ingredients” which the milk already<br />

contained were allowed to be added. This sounded easy, but<br />

it took more than a year for two employees to take the process<br />

from the laboratory to an industrial plant that could produce<br />

a whole milk powder that was cold water-soluble.<br />

The task was solved by spraying a lecithin solution on the<br />

surface of the milk powder particles – a process that customers<br />

lined up to buy.<br />

34 | 35<br />

Need for product quality among customers<br />

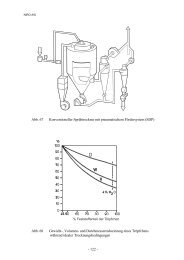

Some of the development projects were inspired by the need<br />

to solve customers’ problems with product quality. The<br />

biggest problem was the density of the milk powder. Almost<br />

all of <strong>Niro</strong>’s milk plants were based on atomization of the<br />

fluid milk concentrate into small particles with a rotating<br />

ato mizer; that is, a component that converts the liquid into<br />

particles, which are then dried to powder.<br />

This resulted in a lighter powder than the one our competitors<br />

– especially from the U.S. and Japan – could produce. Not<br />

even <strong>Niro</strong>’s famous, patented “milk wheel” was able to solve<br />

the problem of product quality. During the energy crisis in<br />

the 1970s, when saving energy was a requirement, plants<br />

able to dry the powder in two steps were developed, since it<br />

is cheaper to remove the residual moisture in a vibrating<br />

after-dryer – called a VIBRO-FLUIDIZER ® – compared to a<br />

spray drying plant.<br />

Two-step drying, as it was called, provided better drying<br />

economy but also a heavier powder. With <strong>Niro</strong>’s high-pressure<br />

nozzles the powder became even heavier, and <strong>Niro</strong> was ahead<br />

of the competition again. But the development activities<br />

didn’t stop there. Customers required even better drying<br />

economy and higher quality drying, and showed interest