Technical highlights - Department of Primary Industries ...

Technical highlights - Department of Primary Industries ...

Technical highlights - Department of Primary Industries ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Spatial pattern analyses indicated<br />

that established and newly recruited<br />

individuals are aggregated and that the<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> aggregation decreases with<br />

plant size. However, after fire, seedling<br />

and juvenile recruitment assume negative<br />

association (spatial displacement/<br />

decoupling) in relation to established<br />

individuals, perhaps in response to<br />

increased lantana litter (fuel load) and thus<br />

more intense temperature build-up around<br />

existing parent plants during burning.<br />

This finding implies that in a landscape<br />

where burning is used as a management<br />

tool, any follow-up with herbicide that<br />

focuses on reducing recruitment can<br />

simply concentrate on spaces between<br />

established individuals, thereby reducing<br />

both herbicide and labour cost.<br />

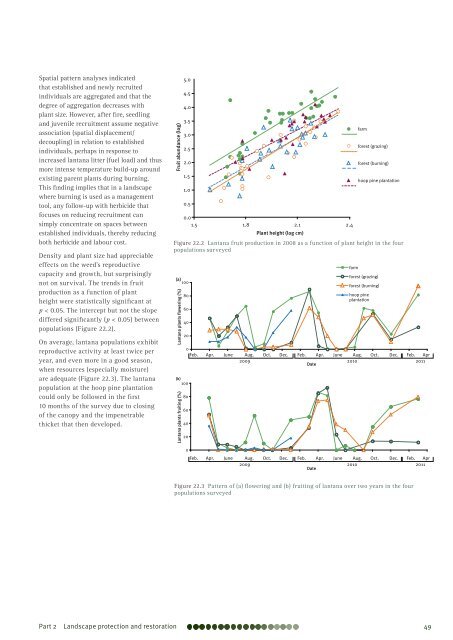

Density and plant size had appreciable<br />

effects on the weed’s reproductive<br />

capacity and growth, but surprisingly<br />

not on survival. The trends in fruit<br />

production as a function <strong>of</strong> plant<br />

height were statistically significant at<br />

p < 0.05. The intercept but not the slope<br />

differed significantly (p < 0.05) between<br />

populations (Figure 22.2).<br />

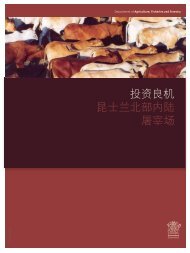

On average, lantana populations exhibit<br />

reproductive activity at least twice per<br />

year, and even more in a good season,<br />

when resources (especially moisture)<br />

are adequate (Figure 22.3). The lantana<br />

population at the hoop pine plantation<br />

could only be followed in the first<br />

10 months <strong>of</strong> the survey due to closing<br />

<strong>of</strong> the canopy and the impenetrable<br />

thicket that then developed.<br />

Fruit abundance (log)<br />

5.0<br />

4.5<br />

4.0<br />

3.5<br />

3.0<br />

2.5<br />

2.0<br />

1.5<br />

1.0<br />

0.5<br />

0.0<br />

1.5 1.8 2.1 2.4<br />

Plant height (log cm)<br />

Part 2 Landscape protection and restoration 49<br />

farm<br />

forest (grazing)<br />

forest (burning)<br />

hoop pine plantation<br />

Figure 22.2 Lantana fruit production in 2008 as a function <strong>of</strong> plant height in the four<br />

populations surveyed<br />

(a)<br />

100<br />

Lantana plants flowering (%)<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

(b)<br />

100<br />

Lantana plants fruiting (%)<br />

0<br />

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb. Apr<br />

2009<br />

Date<br />

2010 2011<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

farm<br />

forest (grazing)<br />

forest (burning)<br />

hoop pine<br />

plantation<br />

0<br />

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb. Apr<br />

2009<br />

Date<br />

2010 2011<br />

Figure 22.3 Pattern <strong>of</strong> (a) flowering and (b) fruiting <strong>of</strong> lantana over two years in the four<br />

populations surveyed