Risk of Anisakidosis related to Fish consumption

Risk of Anisakidosis related to Fish consumption

Risk of Anisakidosis related to Fish consumption

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anisakidosis</strong> <strong>related</strong><br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>consumption</strong><br />

Stefano D’Amelio<br />

Parasi<strong>to</strong>logy Section, Dept. <strong>of</strong> Sciences <strong>of</strong> Public Health, Sapienza University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Rome, Italy

Anisakids are <strong>of</strong> medical and<br />

economic significance. Larval<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> anisakid nema<strong>to</strong>des <strong>of</strong><br />

the genera Anisakis Dujardin,<br />

1845 and Pseudoterranova<br />

Mozgovoi, 1951 are in fact the<br />

principal aethiological agents <strong>of</strong><br />

human anisakidosis.

This fish-borne zoonosis occurs<br />

when the larvae are taken alive<br />

after the <strong>consumption</strong> <strong>of</strong> raw,<br />

undercooked or improperly<br />

processed fish or cephalopods<br />

that serve as paratenic hosts in<br />

the life cycle <strong>of</strong> these<br />

nema<strong>to</strong>des.

Human anisakidosis is becoming <strong>of</strong><br />

major health and economic<br />

importance and it is particular<br />

relevant in countries, such as Japan,<br />

where the number <strong>of</strong> human cases<br />

reach significant peaks owing <strong>to</strong> the<br />

widespread cus<strong>to</strong>m <strong>of</strong> eating<br />

preparations based on raw fish, such<br />

as sushi and sashimi. Human cases<br />

are increasingly reported from United<br />

States and many European countries.

Life cycles<br />

Anisakids are ascaridoid nema<strong>to</strong>des dependent upon<br />

aquatic hosts for the completion <strong>of</strong> their life his<strong>to</strong>ry,<br />

which generally involves an array <strong>of</strong> invertebrates<br />

and fish as intermediate or paratenic hosts, and<br />

marine mammals or fish-eating birds, reptiles and<br />

fishes as definitive hosts.

A simple life cycle?

A complicated life-cycle?<br />

Anisakid nema<strong>to</strong>des are<br />

heteroxenous and their life<br />

cycles involve small<br />

crustaceans as first<br />

intermediate or paratenic<br />

hosts, where maybe second<br />

stage larvae (L2) mutate <strong>to</strong><br />

L3, thus becoming<br />

potentially infective <strong>to</strong> their<br />

definitive hosts. According<br />

<strong>to</strong> new studies, anisakids<br />

reach the third stage within<br />

the egg.<br />

From Abollo, 1999.

Calanus finmarchicus<br />

Paraeuchaeta norvegica<br />

A study on<br />

Maurolicus muelleri

A very complicated life-cycle!<br />

?<br />

?<br />

?

The life cycle <strong>of</strong><br />

Pseudoterranova decipiens s.

Parasite biomass in the life cycle<br />

<strong>of</strong> Anisakis and Pseudoterranova<br />

P = 100%<br />

I = up <strong>to</strong> 10,000<br />

P = 50-80%<br />

I = up <strong>to</strong> 200<br />

P = 2-20%<br />

I = up <strong>to</strong> 5-10<br />

P = 0.2%<br />

I = 1<br />

marine mammals -<br />

definitive host<br />

large fishes/cephalopods -<br />

paratenic host<br />

small fishes - paratenic host<br />

crustacean - intermediate hos

Epizootiology<br />

Anisakid larvae have been detected worldwide in a large<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> fish species. Among teleosts, they have been<br />

found in Gadiformes, Perciformes, Clupeiformes,<br />

Pleuronectiformes, Scorpaeniformes, Zeiformes,<br />

Bericiformes, Lophiiformes, Anguilliformes and<br />

Atheriniformes.

Third stage larvae <strong>of</strong> anisakids are commonly found in the<br />

flesh and the body cavity <strong>of</strong> a large number <strong>of</strong> fishes as<br />

well as in cephalopods that serve as paratenic hosts.<br />

From aquatic.unizar.es/n3/art1401/anisakis.htm

Anisakis sp. larva in the<br />

flesh <strong>of</strong> blue whiting<br />

(Micromesistius poutassou)<br />

after light candling<br />

(from www.usc.es/banim/doc/tppanisa.htm)

Anisakid larvae have been also detected in elasmobranchs<br />

and in a variety <strong>of</strong> cephalopods. Among these, they have<br />

been found in Oc<strong>to</strong>podidae, Sepiidae, Loliginidae and<br />

Ommastrephidae.

Adult forms <strong>of</strong> Anisakis spp. are usually found in cetaceans<br />

(whales and dolphins). Pseudoterranova spp. matures mainly<br />

in pinnipeds (phocids and otariids). Some members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

genus Contracaecum reach maturity in pinnipeds, others in<br />

fish-eating birds (e.g cormorants, pelecans and herons).<br />

Phocascaris species become adults in pinnipeds <strong>of</strong> the<br />

northern hemisphere.

His<strong>to</strong>pathology<br />

His<strong>to</strong>pathological studies in<br />

fish revealed damages mostly<br />

at the level <strong>of</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach wall,<br />

liver, gonads and muscles.<br />

These includes mechanical<br />

damages, necrosis, tissue<br />

compression and castration.<br />

Clinical signs in fishes are<br />

mainly cellular infiltration,<br />

and hemorrhage.<br />

From Abollo, 1999.

His<strong>to</strong>pathological studies in<br />

cephalopods revealed<br />

damages mostly at the level<br />

<strong>of</strong> s<strong>to</strong>mach wall, mantle<br />

muscle, nidamentary<br />

glands, testicle and ovary.<br />

These includes mechanical<br />

damages, necrosis, tissue<br />

compression and castration.<br />

Cellular infiltration is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

found associated <strong>to</strong><br />

encapsulated larvae.<br />

From Abollo et al., 1998.

In the s<strong>to</strong>mach <strong>of</strong> cetaceans,<br />

anisakid adults are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

found in clusters <strong>of</strong><br />

individuals embedded in the<br />

mucosa and submucosa.<br />

Ulcers <strong>of</strong> 5x3 cm sized<br />

associated <strong>to</strong> anisakids are<br />

found in the fundic portion <strong>of</strong><br />

the s<strong>to</strong>mach. From Abollo et al., 1998.

Taxonomy<br />

Eukaryota<br />

Metazoa<br />

Nema<strong>to</strong>da<br />

Secernentea<br />

Ascaridida<br />

Ascaridoidea<br />

Anisakidae<br />

The most frequently recovered anisakid species in fish<br />

belong <strong>to</strong> the following genera:<br />

Anisakis, Pseudoterranova, Contracaecum, Phocascaris

Anisakid larvae can<br />

be identified at<br />

genus level by light<br />

microscopy, mainly<br />

on the basis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

morphology <strong>of</strong><br />

digestive tract and<br />

<strong>of</strong> excre<strong>to</strong>ry system.<br />

A-C Pseudoterranova decipiens; D-F Anisakis sp.; G-I Hysterothylacium<br />

aduncum; J-L Contracaecum rudolphii. (From Anderson, 2000)

The taxonomy <strong>of</strong> anisakids is mainly based on the<br />

morphology <strong>of</strong> male adult specimens. The most<br />

significant structural characters for species<br />

identification are the distribution and pattern <strong>of</strong> caudal<br />

papillae, the spiculae and the morphology <strong>of</strong> cephalic<br />

end (Fagerholm, 1991).<br />

From Abollo et al., 1998.

However, anisakid nema<strong>to</strong>des tend <strong>to</strong> be very<br />

conserved in gross morphology and molecular<br />

techniques have shown that many presumed<br />

monospecific species consists <strong>of</strong> several cryptic<br />

species (Nascetti et al., 1993; Paggi et al., 1991;<br />

Orecchia et al., 1994; Mattiucci et al., 1997).<br />

Molecular markers in the ribosomal DNA spacers<br />

have been recently established for the correct<br />

identification <strong>of</strong> Anisakis cryptic and<br />

morphospecies, irrespective <strong>of</strong> their sex or life<br />

his<strong>to</strong>ry stage (D’Amelio et al., 2000)

Species <strong>of</strong> Anisakis (two main clusters)<br />

One corresponding <strong>to</strong> larvae Type I (7 species)<br />

A. simplex (s.s).<br />

A. pegreffii<br />

A. simplex C<br />

A. ziphidarum<br />

Anisakis sp. A (sensu Pontes et al 2005)<br />

corresponding <strong>to</strong> Anisakis sp. (sensu Valentini et al 2006)<br />

A. typica<br />

A. schupakovi<br />

The other corresponding <strong>to</strong> larvae Type II (3 species)<br />

A. physeteris<br />

A. brevispiculata<br />

A. paggiae

Anisakis simplex s.s.<br />

• mainly in the North Atlantic and North<br />

Pacific Oceans<br />

• found frequently in Balaenoptera<br />

acu<strong>to</strong>rostrata, Delphinus delphis,<br />

Globicephala melaena, Lagenorhynchus<br />

albirostris, Orcinus orca, Stenella<br />

coeruleoalba (rare), Phocoena phocoena,

Anisakis pegreffii<br />

• mainly in the Mediterranean Sea and the<br />

South Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found frequently in Delphinus delphis,<br />

Ziphius cavirostris, Tursiops truncatus

Anisakis simplex C<br />

• mainly in the South Atlantic and North<br />

Pacific Oceans<br />

• found frequently in Pseudorca crassidens,<br />

Ziphius cavirostris

Anisakis ziphidarum<br />

• mainly in the Mediterranean Sea and the<br />

South Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found frequently in Mesoplodon layardii,<br />

Mesoplodon mirus, Ziphius cavirostris all<br />

<strong>of</strong> them members <strong>of</strong> the family Ziphiidae

Anisakis sp. A (sensu Pontes et al.<br />

2005)<br />

• from the coasts <strong>of</strong> Madeira and Galicia<br />

• found in Mesoplodon densirostris

Anisakis typica<br />

• mainly from warm/temperate waters <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found in Sotalia fluviatilis, Stenella<br />

coeruleoalba, Stenella attenuata, Stenella<br />

longirostris, Steno bredanensis,<br />

Lagenodelphis hosei

Anisakis physeteris<br />

• mainly in the Mediterranean and the<br />

Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found frequently in Kogia breviceps, Kogia<br />

sima, Physeter macrocephalus, rarely in<br />

Ziphius cavirostris

Anisakis brevispiculata<br />

• mainly in the Mediterranean and the central<br />

Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found frequently in Kogia breviceps, Kogia<br />

sima, Physeter macrocephalus

Anisakis paggiae<br />

• mainly in the central Atlantic Ocean<br />

• found frequently in Kogia breviceps, Kogia<br />

sima,

Anisakis schupakovi<br />

• endemic <strong>to</strong> the Caspian Sea<br />

• found only in Phoca caspica

The identification <strong>of</strong> anisakid nema<strong>to</strong>des can be performed<br />

by morphological study and by genetic characterisation by<br />

PCR-RFLP analysis. The genomic region <strong>of</strong> the ribosomal<br />

DNA spanning the ITS-1, the 5.8S and the ITS-2 is<br />

amplified by PCR. Amplicons are subjected <strong>to</strong> restriction<br />

analysis using those endonucleases that provides<br />

diagnostic patterns in anisakids.

HhaI<br />

HinfI<br />

TaqI<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 L<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 L<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 L<br />

< 500bp<br />

< 500bp<br />

< 500bp<br />

1 A.pegreffii<br />

2 A.simplex s.s.<br />

3 A.simplex C<br />

4 A.physeteris<br />

5 A.schupakovi<br />

6 A.ziphidarum<br />

7 A.typica<br />

L 100 bp ladder

Species <strong>of</strong> Pseudoterranova<br />

Five members <strong>of</strong> the Pseudoterranova decipiens complex<br />

P. krabbei,<br />

P. decipiens (s.s.)<br />

P. bulbosa,<br />

P. azarasi<br />

P. decipiens E<br />

P. cattani<br />

P. ceticola<br />

P. kogiae

Pseudoterranova krabbei<br />

• mainly from the coasts <strong>of</strong> Scotland,<br />

Norway, Iceland<br />

• found frequently in Halichoerus grypus

Pseudoterranova decipiens s.s.<br />

• mainly from the coasts <strong>of</strong> Scotland,<br />

Norway, Iceland, but also in Pacific Canada<br />

and Japan<br />

• found frequently in Phoca vitulina

Pseudoterranova bulbosa<br />

• mainly from the coasts <strong>of</strong> North Norway,<br />

Iceland and Greenland but also in Northern<br />

Pacific Canada and Japan<br />

• found frequently in Erignathus barbatus

Pseudoterranova azarasi<br />

• mainly from the coasts <strong>of</strong> Japan<br />

• found frequently in Eume<strong>to</strong>pias jubatus but<br />

also in Erignathus barbatus

Pseudoterranova decipiens E<br />

• mainly from the coasts <strong>of</strong> the Antarctica<br />

• found frequently in Lep<strong>to</strong>nychotes weddelli

Pseudoterranova cattani<br />

• mainly from the Pacific coasts <strong>of</strong> South<br />

America<br />

• found frequently in Otaria byronia

Pseudoterranova kogiae and P.<br />

ceticola<br />

• mainly from the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico and<br />

adjacent waters<br />

• found in Kogia sima, Kogia breviceps

The species <strong>of</strong><br />

Pseudoterranova<br />

can be<br />

distinguished by<br />

SSCP analysis

Anisakis in fish (paratenic hosts) and<br />

marine mammals (definitive hosts)<br />

Results from a large survey carried<br />

out by Lia Paggi and collabora<strong>to</strong>rs

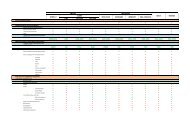

Prevalence, abundance and intensity <strong>of</strong> Anisakis spp. in the Mediterranean<br />

Sea

Prevalence, abundance and intensity <strong>of</strong> Anisakis pegreffii in the Southern<br />

Atlantic Ocean

Prevalence, abundance and intensity <strong>of</strong> Anisakis simplex s.s. in the Northern<br />

Atlantic Ocean

Prevalence, abundance and intensity <strong>of</strong> Anisakis simplex s.s. in the Northern<br />

Pacific Ocean

arine mammalsasdefinitive hostsforAnisakis spp.

Portugal<br />

(Marquez et al., 2006)

Portugal<br />

(Marquez et al., 2006)

Portugal<br />

revalence, intensity and abundance <strong>of</strong> anisakid larvae in Pagellus<br />

ogaraveo, relative <strong>to</strong> fish length, from Madeiran waters. (Costa et<br />

., 2004)<br />

Length<br />

class<br />

(cm)<br />

≤ 25<br />

25-35<br />

≥ 35<br />

n fish<br />

examined<br />

16<br />

34<br />

27<br />

n.<br />

infected<br />

fish<br />

13<br />

30<br />

26<br />

Prevalence<br />

(%)<br />

81.3<br />

88.2<br />

96.3<br />

n parasites<br />

(min-max.)<br />

47 (1-10)<br />

144 (1-36)<br />

90 (1-17)<br />

Mean<br />

Intensity<br />

±S.E.<br />

3.6 ±0.8<br />

4.8±2.0<br />

3.5 ±0.8<br />

Abundance<br />

±S.E.<br />

2.9 ±0.7<br />

4.2 ± 1.2<br />

3.3 ± 0.7

Portugal<br />

gain from Madeiran waters. (Costa et al., 2003)<br />

Host species<br />

Aphanopus<br />

carbo<br />

Scomber<br />

japonicus<br />

Trachurus<br />

picturatus<br />

n fish<br />

examined<br />

142<br />

150<br />

40<br />

Prevalence<br />

(%)<br />

97.2<br />

69.5<br />

62.5<br />

Mean Intensity<br />

69.6<br />

2.6<br />

2.5

Spain<br />

Abollo et al, 2001

VIGO<br />

PENICHE<br />

LASTRES ZUMAIA<br />

CADIZ<br />

SAMPLING<br />

MALAGA<br />

MOTRIL<br />

ALMUÑECAR

HinfI<br />

RG AP AS L<br />

RG: recombinant genotype<br />

AP: Anisakis pegreffii<br />

AS: Anisakis simplex s.s.<br />

L: 100 bp ladder

A. pegreffii<br />

A. simplex s.s.<br />

Recombinant genotype

. simplex s.s.: 84.0%<br />

. pegreffii: 4.0%<br />

ecombinant: 12.0%<br />

VIGO<br />

A. simplex s.s.: 62.0%<br />

A. pegreffii: 38.0%<br />

Recombinant: 0.0%<br />

PENICHE<br />

A. simplex s.s.: 55.2%<br />

A. pegreffii: 31.6%<br />

Recombinant: 13.2%<br />

simplex s.s.: 12.5%<br />

pegreffii: 66.7%<br />

combinant: 20.8%<br />

LASTRES<br />

CADIZ<br />

ZUMAIA<br />

ALBORAN<br />

SEA<br />

A. simplex s.s.: 85.7%<br />

A. pegreffii: 0.0%<br />

Recombinant: 14.3%<br />

A. simplex s.s.: 28.6%<br />

A. pegreffii: 50.0%<br />

Recombinant: 21.4%

Anisakis in Phycis from Andalucia

Anisakis in Phycis from Tunisia

Poland<br />

Two subspecies <strong>of</strong> herring from the Baltic Sea<br />

Clupea harengus membras (Baltic endemic subspecies)<br />

Clupea harengus harengus (spring-spawning migrations)<br />

Data on Anisakis spp. show that Baltic endemic herrings<br />

are virtually Anisakis-free, and that the risk is <strong>related</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

herrings migrating from the North Sea<br />

Multilocus allozymes provided data that support this<br />

hypothesis (Mattiucci et al., 1989).

Poland<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> Anisakis spp. from two geographically<br />

distinct areas (Western Baltic and Irish Sea) has<br />

found a <strong>to</strong>tal <strong>of</strong> eight polymorphic sites over a 250<br />

base sequence <strong>of</strong> the CO1 region. Three haplotypes<br />

were identified from Irish Sea parasites and six<br />

haplotypes from the Western Baltic samples.<br />

Geographical<br />

Region<br />

Poly Poly morp hic sites<br />

(nucleotide p ositions)<br />

Haplotype 88 89 94 115 140 182 201 243<br />

Irish sea A T T T C T C C C<br />

Irish sea B T T T T T C T C<br />

Irish sea C C T T T C C C C<br />

B altic sea D C C T C T C T C<br />

B altic sea E C T T C T C C C<br />

B altic sea F C T T T T T C C<br />

B altic sea G C T T T T C C A<br />

B altic sea H T T T T T C C C<br />

B altic sea I C T C T T C C C

Anisakids from Mexico<br />

(fish used for “cebiche”)<br />

ata from Laffon Leal et al., 2000<br />

Host species<br />

Epinephelus<br />

morio<br />

Sphyraena<br />

barracuda<br />

Gerres<br />

cinereus<br />

Prevalence<br />

(%)<br />

83<br />

33<br />

57<br />

Contracaecum spp.<br />

Mean Intensity<br />

6.5<br />

10.2<br />

7.6

Clinically, several different types <strong>of</strong> human anisakidosis have<br />

been defined based on the location (gastric, intestinal or<br />

extra-gastrointestinal) (Ohtaki and Ohtaki, 1989; Ishikura,<br />

1990; Yoshimura, 1990) and on his<strong>to</strong>pathological<br />

classification (Kojima et al., 1966).

Gastric anisakidosis is characterized by a selflimited,<br />

self-healing episode <strong>of</strong> intense<br />

epigastralgia, nausea, and vomiting 2 <strong>to</strong> 5 hours<br />

after ingestion <strong>of</strong> raw fish.<br />

Endoscopic removal <strong>of</strong> the larvae is curative.<br />

Diagnosis <strong>of</strong> gastric anisakidosis can be made<br />

based on morphology <strong>of</strong> the whole worm when<br />

expec<strong>to</strong>rated by the patient or after endoscopic<br />

removal.

Gastroendoscopic image showing a Anisakis larva<br />

extracted from the gastric tract <strong>of</strong> a 51 year old<br />

woman in Southern Italy (D’Amelio et al., 1999)

Section <strong>of</strong> Anisakis larva in the ileum <strong>of</strong> a patient.<br />

(From http://www.stanford.edu/class/humbio103/parasitepages/ParaSites/anisakiasis/Diag.html)

Intestinal anisakiosis presents as low abdominal pain.<br />

Intestinal anisakiosis is extremely difficult <strong>to</strong> diagnose<br />

clinically because <strong>of</strong> the nonspecificity <strong>of</strong> the symp<strong>to</strong>ms.<br />

In fact, the majority <strong>of</strong> cases are initially misdiagnosed as<br />

appendicitis, acute abdominal syndrome, cancer (gastric<br />

or intestinal), ileitis including Crohn disease, or<br />

tuberculous peri<strong>to</strong>nitis.<br />

A his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> raw marine fish ingestion is the most<br />

important clinical feature, and anisakiosis should be<br />

considered in anyone with a his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> ingestion <strong>of</strong> raw<br />

marine fish and abdominal pain. Peripheral eosinophilia<br />

may be observed but it is not specific.

Cross section through the intestinal region <strong>of</strong> the nema<strong>to</strong>de.<br />

Note the external cuticle (C) overlying a celomyarian and<br />

polymyarian muscle layer (M), lateral epidermal cords<br />

(LEC), and the digestive tract (DT) with a single layer <strong>of</strong><br />

columnar epithelial cells determining a central tripartite

Recently, larval forms <strong>of</strong> A. simplex have<br />

been identified as responsable <strong>of</strong> IgEmediated<br />

allergic reactions, with<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>ms ranging from urticaria, <strong>to</strong><br />

asthma up <strong>to</strong> anaphylactic shock<br />

(Audicana et al., 2002).<br />

umber <strong>of</strong> papers in Pubmed<br />

ter a search under “Anisakis<br />

lergy”<br />

18<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Which treatment for make the larvae<br />

not harmful?<br />

• Heat (recommended at least 66°C, but …<br />

• Freezing (24h at -20°C)<br />

• Acid treatment<br />

• Salt, vinegar, smoke

Which treatment for make the larvae<br />

not harmful?<br />

• FDA recommends that all fish and shellfish<br />

intended for raw (or semiraw such as<br />

marinated or partly cooked) <strong>consumption</strong> be<br />

blast frozen <strong>to</strong> -35°C or below for 15 hours,<br />

or be regularly frozen <strong>to</strong> -20°C or below for<br />

7 days.

In the samples where the temperature rises (heat and<br />

microwaves), the surface <strong>of</strong> the parasites shows<br />

disrupted zones where the cuticle is damaged.<br />

Live larvae with a damaged cuticle may be<br />

susceptible <strong>to</strong> the action <strong>of</strong> enzymes and acid<br />

conditions <strong>of</strong> the gastric solutions when consumed,<br />

with the result <strong>of</strong> fragmentation and dissolution <strong>of</strong><br />

the larvae and its death, before the attachment <strong>to</strong> and<br />

penetration <strong>of</strong> the mucosa (1). In this case, no<br />

anisakiasis occurs when the larva is ingested.<br />

However, the allergic response in sensitized<br />

individuals may increase due <strong>to</strong> the release <strong>of</strong><br />

somatic allergens, some <strong>of</strong> them heat and pepsin<br />

resistant, which are not protected by the cuticle from<br />

the gastric juices. This would explain the cases <strong>of</strong><br />

allergy in patients sensitized <strong>to</strong> Anisakis after the<br />

ingestion <strong>of</strong> well-cooked canned

Anisakis and Pseudoterranova<br />

• A nice model study?<br />

• A useful <strong>to</strong>ol?<br />

only a risk?

Anisakis and Pseudoterranova<br />

a model study<br />

• Population genetics<br />

• Detection <strong>of</strong> sibling species<br />

• Detection <strong>of</strong> an hybrid zone<br />

• Host-parasite coevolution

0.02<br />

85<br />

100<br />

94<br />

100<br />

79<br />

29A.brevispiculata<br />

58 A.brevispiculata<br />

100 A. brevispiculata<br />

A. brevispiculata<br />

67A.<br />

brevispiculata<br />

A.physeteris<br />

100 A.physeteris<br />

A.paggiae<br />

100A.paggiae<br />

80 P.ceticola<br />

P.ceticola<br />

85 P.ceticola<br />

66 P.ceticola<br />

Anisakis sp from madeira<br />

A.ziphidarum<br />

50 A.simplexC<br />

A.simplexs.s.<br />

100 A.pegreffii<br />

67 A.pegreffii<br />

A.typica<br />

A.typica<br />

85 A.typica<br />

A.typica<br />

56 A.typica<br />

Atypica<br />

A.typica<br />

Sperm whales<br />

Kogia and Physeter<br />

Beaked whales<br />

Baleen whales<br />

and dolphins<br />

Dolphins

Anisakis and Pseudoterranova<br />

a model study<br />

• Anisakis species as indica<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> fish s<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

biology

Mattiucci et al., 2004

References:<br />

Abollo E (1999). Anisaquidos en aguas de Galicia: del gen al ecosistema (PhD Thesis, Universidade de Vigo)<br />

Abollo E, Gestal C, Lopez A, Gonzalez A, Guerra A, Pascual S (1998). Squids as trophic bridges for parasite flow within marine<br />

ecosystems: the case <strong>of</strong> Anisakis simplex (Nema<strong>to</strong>da: Anisakidae) or when the wrong way can be right. In Payne AIL, Lipinsky MR,<br />

Clarke MR, Roeleveld MAC eds. S Afr J Mar Sci 20: 207-223<br />

Anderson RC (2000). Nema<strong>to</strong>de parasites <strong>of</strong> vertebrates, their development and transmission. CABI Publishing<br />

Audicana MT, Ansotegui IJ, Fernandez de Corres L, Kennedy MW (2002). Anisakis simplex: dangerous - dead and alive? Trends<br />

Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 18: 20-25.<br />

D’Amelio S, Mathiopoulos KD, Brandonisio O, Lucarelli G, Doronzo F, Paggi L (1999). Diagnosis <strong>of</strong> a case <strong>of</strong> gastric anisakidosis by<br />

PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Parassi<strong>to</strong>logia 41: 591-593.<br />

D’Amelio S, Mathiopoulos KD, San<strong>to</strong>s CP, Pugachev ON, Webb SC, Picanço M, Paggi L (2000). Genetic markers in ribosomal DNA<br />

for the identification <strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> the genus Anisakis (Nema<strong>to</strong>da: Ascaridoidea) defined by PCR-based RFLP. Int J Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 30 (2):<br />

223-226.<br />

Fagerholm, HP (1991). Systematic implications <strong>of</strong> male caudal morphology in ascaridoid nema<strong>to</strong>de parasites. Syst Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 19: 215-<br />

228<br />

Ishikura H (1990). Clinical Features <strong>of</strong> Intestinal Anisakiasis. In: Intestinal Anisakiasis in Japan (Ishikura H, Kikuchi K Eds) Springer-<br />

Verlag Tokio pp. 89-100.<br />

Kojima K, Koyanagi T, Shiraki K (1966). Pathological studies <strong>of</strong> anisakiasis (parasitic abscess formation in gastrointestinal tracts). Jpn<br />

J Clin Med 24: 134-143.<br />

Mattiucci S, Nascetti G, Cianchi R, Paggi L, Arduino P, Margolis L, Brattey J, Webb S, D’Amelio S, Orecchia P, Bullini L (1997).<br />

Genetic and ecological data on the Anisakis simplex complex with evidence for a new species (Nema<strong>to</strong>da, Ascaridoidea, Anisakidae). J<br />

Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 83: 401-416.<br />

Nascetti G, Cianchi R, Mattiucci S, D’Amelio S, Orecchia P, Paggi L, Brattey J, Berland B, Smith JW, Bullini L (1993).<br />

Three sibling species within Contracaecum osculatum (Nema<strong>to</strong>da, Ascaridida, Ascaridoidea) from the Atlantic Arctic-boreal region:<br />

reproductive isolation and host preferences. Int J Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 23: 105 120.<br />

Ohtaki H, Ohtaki R (1989). Clinical Manifestation <strong>of</strong> Gastric Anisakiasis. In: Gastric Anisakiasis in Japan (Ishikura H, Namiki M Eds)<br />

Springer-Verlag Tokio pp. 37-46.<br />

Orecchia P, Mattiucci S, D’Amelio S, Paggi L, Plotz J, Cianchi R, Nascetti G, Arduino P, Bullini L (1994). Two new<br />

members in the Contracaecum osculatum complex (Nema<strong>to</strong>da, Ascaridoidea) from the Antarctic. Int J Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 24: 367-377.<br />

Paggi L, Nascetti G, Cianchi R, Orecchia P, Mattiucci S, D’Amelio S, Berland B, Brattey J, Smith JW, Bullini L (1991). Genetic<br />

evidence for three species within Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nema<strong>to</strong>da, Ascaridida, Ascaridoidea) in the North Atlantic and<br />

Norwegian and Barents Seas. Int J Parasi<strong>to</strong>l 21: 195-212.<br />

Yoshimura H (1990). Clinical Patho-Parasi<strong>to</strong>logy <strong>of</strong> Extra-Gastrointestinal Anisakiasis. In: Intestinal Anisakiasis in Japan (Ishikura H,<br />

Kikuchi K Eds) Springer Verlag pp. 145-154.

![Emilia Romagna [PDF - 175.10 kbytes]](https://img.yumpu.com/23556597/1/184x260/emilia-romagna-pdf-17510-kbytes.jpg?quality=85)

![Istisan Congressi N. 66 (Pag. 1 - 81). [PDF - 2021.12 kbytes] - Istituto ...](https://img.yumpu.com/23556493/1/171x260/istisan-congressi-n-66-pag-1-81-pdf-202112-kbytes-istituto-.jpg?quality=85)