FOR iPad > OPEN IN IBOOKS - CIJintl.com

FOR iPad > OPEN IN IBOOKS - CIJintl.com

FOR iPad > OPEN IN IBOOKS - CIJintl.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

sensibility<br />

good don’t have to be mutually exclusive<br />

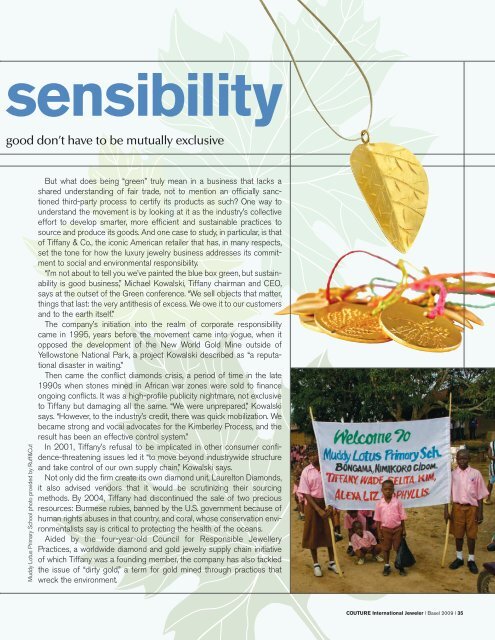

Muddy Lotus Primary School photo provided by Ruff&Cut<br />

But what does being “green” truly mean in a business that lacks a<br />

shared understanding of fair trade, not to mention an officially sanctioned<br />

third-party process to certify its products as such? One way to<br />

understand the movement is by looking at it as the industry’s collective<br />

effort to develop smarter, more efficient and sustainable practices to<br />

source and produce its goods. And one case to study, in particular, is that<br />

of Tiffany & Co., the iconic American retailer that has, in many respects,<br />

set the tone for how the luxury jewelry business addresses its <strong>com</strong>mitment<br />

to social and environmental responsibility.<br />

“I’m not about to tell you we’ve painted the blue box green, but sustainability<br />

is good business,” Michael Kowalski, Tiffany chairman and CEO,<br />

says at the outset of the Green conference. “We sell objects that matter,<br />

things that last: the very antithesis of excess. We owe it to our customers<br />

and to the earth itself.”<br />

The <strong>com</strong>pany’s initiation into the realm of corporate responsibility<br />

came in 1995, years before the movement came into vogue, when it<br />

opposed the development of the New World Gold Mine outside of<br />

Yellowstone National Park, a project Kowalski described as “a reputational<br />

disaster in waiting.”<br />

Then came the conflict diamonds crisis, a period of time in the late<br />

1990s when stones mined in African war zones were sold to finance<br />

ongoing conflicts. It was a high-profile publicity nightmare, not exclusive<br />

to Tiffany but damaging all the same. “We were unprepared,” Kowalski<br />

says. “However, to the industry’s credit, there was quick mobilization. We<br />

became strong and vocal advocates for the Kimberley Process, and the<br />

result has been an effective control system.”<br />

In 2001, Tiffany’s refusal to be implicated in other consumer confidence-threatening<br />

issues led it “to move beyond industrywide structure<br />

and take control of our own supply chain,” Kowalski says.<br />

Not only did the firm create its own diamond unit, Laurelton Diamonds,<br />

it also advised vendors that it would be scrutinizing their sourcing<br />

methods. By 2004, Tiffany had discontinued the sale of two precious<br />

resources: Burmese rubies, banned by the U.S. government because of<br />

human rights abuses in that country, and coral, whose conservation environmentalists<br />

say is critical to protecting the health of the oceans.<br />

Aided by the four-year-old Council for Responsible Jewellery<br />

Practices, a worldwide diamond and gold jewelry supply chain initiative<br />

of which Tiffany was a founding member, the <strong>com</strong>pany has also tackled<br />

the issue of “dirty gold,” a term for gold mined through practices that<br />

wreck the environment.<br />

COUTURE International Jeweler l Basel 2009 l 35