Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SWISS SOCIETY OF NEONATOLOGY<br />

<strong>Cardiomegaly</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>premature</strong><br />

<strong>neonate</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>venous</strong><br />

<strong>umbilical</strong> catheterization<br />

JULY 2008

Schlapbach LJ, Pfammatter J-P, Nelle M, McDougall<br />

FJ, Division of Neonatology (SLJ, NM, McDFJ), Divi-<br />

sion of Pediatric Cardiology (PJ-P), Department of<br />

Pediatrics, University of Berne, Switzerland<br />

© Swiss Society of Neonatology, Thomas M Berger, Webmaster

Umbilical <strong>venous</strong> catheters (UVC) are frequently used <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>neonate</strong>s requir<strong>in</strong>g hyperosmolar parenteral nutrition,<br />

catecholam<strong>in</strong>es or when no peripheral <strong>venous</strong> access<br />

can be established. Catheterization of the <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

ve<strong>in</strong> allows rapid central access, but may be associated<br />

with various complications (1). Cl<strong>in</strong>icians are particular-<br />

ly aware of catheter-associated <strong>in</strong>fections and throm-<br />

bosis. Due to the widespread use of <strong>umbilical</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es,<br />

neonatologists should keep rare complications <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d<br />

as well. We present a case of a newborn with pericar-<br />

dial effusion follow<strong>in</strong>g UVC placement.<br />

An extremely <strong>premature</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant weigh<strong>in</strong>g 590 grams<br />

was born at 5 weeks gestational age by caesarean<br />

section for severe pre-eclampsia and deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g fetal<br />

Doppler studies. The baby was <strong>in</strong>tubated for respiratory<br />

distress syndrome with<strong>in</strong> the first hour of life and um-<br />

bilical <strong>venous</strong> and arterial l<strong>in</strong>es were placed (UVC .5<br />

Charrière s<strong>in</strong>gle-lumen, UAC .5 Charrière, ArgyleTM<br />

polyurethane, Tyco Healthcare, Tullamore, Ireland). The<br />

position of the catheters, both of which had been <strong>in</strong>-<br />

serted too far (Fig. 1), was corrected accord<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

CXR by 1.5 cm (UVC) and cm (UAC). After receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

porc<strong>in</strong>e surfactant (Curosurf®), the <strong>in</strong>fant was success-<br />

fully weaned from mechanical ventilation. CXR before<br />

planned extubation on day three unexpectedly sho-<br />

wed cardiomegaly with a heart-to-lung ratio of 0.69<br />

(Fig. ). Echocardiography was performed immediate-<br />

ly and revealed a large echo-free pericardial effusion<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

CASE REPORT

DISCUSSION<br />

measur<strong>in</strong>g 6 mm <strong>in</strong> diameter (Fig. ). Both atrial and<br />

ventricular function were adequate, without diastolic<br />

<strong>in</strong>dentation of the atrial wall. The UVC tip was float<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the right atrium. On the X-ray, the UVC was still<br />

positioned too high project<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the cardiac silhou-<br />

ette (Fig. ), although its <strong>in</strong>itial position had been ade-<br />

quately corrected. Aspiration through the UVC yielded<br />

bloody fluid, and blood gas and chemical analysis of the<br />

aspirate were consistent with blood and not parenteral<br />

nutrition. Ultrasound exam<strong>in</strong>ation ruled out pleural and<br />

abdom<strong>in</strong>al effusions. Stool cultures of the <strong>in</strong>fant and<br />

the mother were negative for enterovirus. Maternal se-<br />

rologies were negative for TORCHS, Parvovirus B19, and<br />

Coxiella burnetii.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the <strong>in</strong>fant rema<strong>in</strong>ed hemodynamically stable with<br />

no signs of cardiovascular compromise, we decided<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st emergency pericardiocentesis. After remov<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the UVC, the effusion gradually resolved with<strong>in</strong> a few<br />

days, and the <strong>in</strong>fant was successfully extubated. The<br />

later cl<strong>in</strong>ical course was complicated by bronchopul-<br />

monary dysplasia and osteopathy of prematurity. Later<br />

cardiac follow-up revealed no functional or anatomical<br />

pathology.<br />

Pericardial effusion is a well-known complication of<br />

peripherally <strong>in</strong>serted central catheters (PICC), with an<br />

estimated <strong>in</strong>cidence of 1.8/1000 catheters ( ). The ma-<br />

jority of <strong>in</strong>fants with reported pericardial effusion beca-

5<br />

me acutely symptomatic due to cardiac tamponade and<br />

deteriorated rapidly with signs of respiratory distress,<br />

cyanosis, tachycardia or bradycardia, mottled sk<strong>in</strong>, and<br />

arterial hypotension f<strong>in</strong>ally lead<strong>in</strong>g to cardiopulmonary<br />

arrest not responsive to standard <strong>in</strong>terventions ( ). No-<br />

tably, approximately a quarter of the cases were first<br />

diagnosed post-mortem at autopsy ( ). The mortality is<br />

very high ( 5-65%) ( , ) and those resuscitated success-<br />

fully improved only <strong>after</strong> emergency pericardiocentesis<br />

was performed. Analysis of the aspirated liquid usually<br />

reflected the composition of the parenteral nutrition.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g a series of case reports on <strong>in</strong>fant deaths attri-<br />

buted to PICC-associated cardiac tamponade, guidel<strong>in</strong>es<br />

have been published aimed at reduc<strong>in</strong>g the risk of car-<br />

diac perforation ( -5).<br />

Contrary to PICC, the <strong>in</strong>cidence of pericardial effusion<br />

associated with UVC is unknown but case reports have<br />

documented sudden cardiovascular compromise <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<br />

fants with UVC due to pericardial tamponade (6-8).<br />

Perforation and catheter migration are thought to occur<br />

as a result of both mechanical pressure by the catheter<br />

tip repeatedly push<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the contract<strong>in</strong>g heart<br />

wall and endocardial <strong>in</strong>jury caused by hyperosmotic pa-<br />

renteral nutrition fluids. Transmural diffusion of paren-<br />

teral nutrition fluids <strong>in</strong>to the pericardial space further<br />

contributes to the accumulation of fluid. Contrary to<br />

catheter-associated <strong>in</strong>fections and thrombosis which<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease over time, pericardial effusion may occur directly

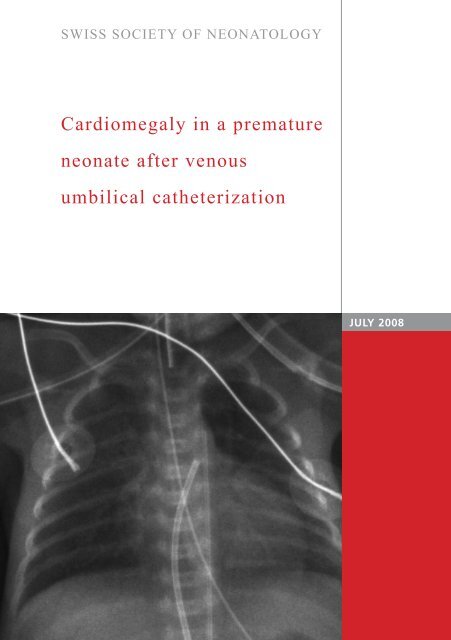

Fig. 1<br />

UVC<br />

UAC<br />

Chest X-ray on day one <strong>after</strong> <strong>in</strong>tubation and <strong>in</strong>sertion<br />

of <strong>venous</strong> (UVC) and arterial (UAC) <strong>umbilical</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

6

UVC<br />

UAC<br />

Incidental f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of cardiomegaly on chest X-ray<br />

before extubation on day three. UVC: <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

<strong>venous</strong> catheter; UAC: <strong>umbilical</strong> arterial catheter.<br />

Fig. 2

<strong>after</strong> <strong>in</strong>sertion of catheters, or later, with a peak at<br />

three days follow<strong>in</strong>g catheter <strong>in</strong>sertion ( ). Malposition<br />

of central catheters is considered the ma<strong>in</strong> risk factor<br />

for pericardial effusion, particularly if the catheter tip<br />

projects <strong>in</strong>to the right atrium or shows angulation ( ,<br />

). The catheter tip should be positioned at the junction<br />

of the vena cava <strong>in</strong>ferior and right atrium with the tip<br />

ly<strong>in</strong>g outside the cardiac silhouette. However, catheter<br />

<strong>in</strong>ward migration, as experienced <strong>in</strong> the present case,<br />

has been described and is attributed to retraction of<br />

the mummify<strong>in</strong>g cord, changes <strong>in</strong> abdom<strong>in</strong>al girth and<br />

catheter dislocation dur<strong>in</strong>g manipulations (6, 9). The-<br />

refore, even <strong>after</strong> correct <strong>in</strong>itial placement, the UVC<br />

position should be checked regularly us<strong>in</strong>g X-ray or<br />

ultrasound.<br />

The differential diagnosis of neonatal pericardial effu-<br />

sion <strong>in</strong>cludes immune and non-immune hydrops fetalis,<br />

congenital <strong>in</strong>fections such as TORCHS and Parvovirus<br />

B19, and rarely myopericarditis caused by Enteroviridae,<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly Echovirus and Cocksackievirus, or Coxiella burnetii.<br />

The present case illustrates that pericardial effusion<br />

may progress asymptomatically before hemodynamic<br />

changes become evident. The <strong>in</strong>cidence of catheter-asso-<br />

ciated pericardial effusion may therefore be underesti-<br />

mated. Extremely low birth-weight <strong>in</strong>fants might be at<br />

particular risk due to the th<strong>in</strong> myocardial wall with rela-<br />

tively large catheters often - as <strong>in</strong> this case - be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>i-<br />

tially <strong>in</strong>serted too far. Consider<strong>in</strong>g the potentially lethal<br />

8

9<br />

*<br />

*<br />

*<br />

Echocardiography demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g large pericardial<br />

effusion (asterisks) on day three.<br />

*<br />

Fig. 3

complications of UVC, neonatologists should carefully<br />

consider the <strong>in</strong>dication for plac<strong>in</strong>g UVCs and remove<br />

UVCs as soon as possible. Whether percutaneous long<br />

l<strong>in</strong>es represent a safer alternative rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear and<br />

further prospective studies compar<strong>in</strong>g UVC and PICC<br />

are needed (1). Mal-positioned UVCs should be cor-<br />

rected immediately and the position should be verified<br />

<strong>after</strong>wards. F<strong>in</strong>ally, neonatologists should ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a<br />

high <strong>in</strong>dex of suspicion for pericardial tamponade and<br />

readily perform echocardiography <strong>in</strong> acutely ill <strong>in</strong>fants<br />

with UVCs.<br />

In conclusion, pericardial effusion may occur asympto-<br />

matically <strong>after</strong> <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheterization and<br />

should be suspected <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with central catheters<br />

and progressive cardiomegaly. Prompt removal of ca-<br />

theters and, if signs of pericardial tamponade are pre-<br />

sent, emergency pericardiocentesis, may prove life-sav<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

For related cases, see also COTM 10/ 001 and COTM<br />

1 / 00 .<br />

10

11<br />

1. Butler-O‘Hara M, Buzzard CJ, Reubens L, McDermott MP,<br />

DiGrazio W, D‘Angio CT. A randomized trial compar<strong>in</strong>g<br />

long-term and short-term use of <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheters<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>premature</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with birth weights of less than<br />

1 51 grams. Pediatrics 006;118:e 5- 5<br />

. Beardsall K, White DK, P<strong>in</strong>to EM, Kelsall AW. Pericardial ef<br />

fusion and cardiac tamponade as complications of neonatal<br />

long l<strong>in</strong>es: are they really a problem? Arch Dis Child Fetal<br />

Neonatal Ed 00 ;88:F 9 - 95<br />

. Darl<strong>in</strong>g JC, Newell SJ, Mohamdee O, Uzun O, Cull<strong>in</strong>ane CJ,<br />

Dear PR. Central <strong>venous</strong> catheter tip <strong>in</strong> the right atrium: a risk<br />

factor for neonatal cardiac tamponade. J Per<strong>in</strong>atol 001;<br />

1: 61- 6<br />

. Nowlen TT, Rosenthal GL, Johnson GL, Tom DJ, Vargo TA.<br />

Pericardial effusion and tamponade <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with central<br />

catheters. Pediatrics 00 ;110:1 -1<br />

5. Pezzati M, Filippi L, Chiti G, Dani C, Rossi S, Bert<strong>in</strong>i G,<br />

Rubaltelli FF. Central <strong>venous</strong> catheters and cardiac tamponade<br />

<strong>in</strong> preterm <strong>in</strong>fants. Intensive Care Med 00 ; 0: 5 - 56<br />

6. Traen M, Schepens E, Laroche S, van Overmeire B. Cardiac<br />

tamponade and pericardial effusion due to <strong>venous</strong> <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

catheterization. Acta Paediatr 005;9 :6 6-6 8<br />

. Sehgal A, Cook V, Dunn M. Pericardial effusion associated<br />

with an appropriately placed <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheter.<br />

J Per<strong>in</strong>atol 00 ; : 1 - 19<br />

8. Onal EE, Saygili A, Koc E, Turkyilmaz C, Okumus N, Atalay Y.<br />

Cardiac tamponade <strong>in</strong> a newborn because of <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong><br />

catheterization: is correct position safe? Paediatr Anaesth<br />

00 ;1 :95 -956<br />

9. Salvadori S, Piva D, Filippone M. Umbilical <strong>venous</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

displacement as a consequence of abdom<strong>in</strong>al girth variation.<br />

J Pediatr 00 ;1 1:<br />

REFERENCES