Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

Cardiomegaly in a premature neonate after venous umbilical ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SWISS SOCIETY OF NEONATOLOGY<br />

<strong>Cardiomegaly</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>premature</strong><br />

<strong>neonate</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>venous</strong><br />

<strong>umbilical</strong> catheterization<br />

JULY 2008

Schlapbach LJ, Pfammatter J-P, Nelle M, McDougall<br />

FJ, Division of Neonatology (SLJ, NM, McDFJ), Divi-<br />

sion of Pediatric Cardiology (PJ-P), Department of<br />

Pediatrics, University of Berne, Switzerland<br />

© Swiss Society of Neonatology, Thomas M Berger, Webmaster

Umbilical <strong>venous</strong> catheters (UVC) are frequently used <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>neonate</strong>s requir<strong>in</strong>g hyperosmolar parenteral nutrition,<br />

catecholam<strong>in</strong>es or when no peripheral <strong>venous</strong> access<br />

can be established. Catheterization of the <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

ve<strong>in</strong> allows rapid central access, but may be associated<br />

with various complications (1). Cl<strong>in</strong>icians are particular-<br />

ly aware of catheter-associated <strong>in</strong>fections and throm-<br />

bosis. Due to the widespread use of <strong>umbilical</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es,<br />

neonatologists should keep rare complications <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d<br />

as well. We present a case of a newborn with pericar-<br />

dial effusion follow<strong>in</strong>g UVC placement.<br />

An extremely <strong>premature</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant weigh<strong>in</strong>g 590 grams<br />

was born at 5 weeks gestational age by caesarean<br />

section for severe pre-eclampsia and deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g fetal<br />

Doppler studies. The baby was <strong>in</strong>tubated for respiratory<br />

distress syndrome with<strong>in</strong> the first hour of life and um-<br />

bilical <strong>venous</strong> and arterial l<strong>in</strong>es were placed (UVC .5<br />

Charrière s<strong>in</strong>gle-lumen, UAC .5 Charrière, ArgyleTM<br />

polyurethane, Tyco Healthcare, Tullamore, Ireland). The<br />

position of the catheters, both of which had been <strong>in</strong>-<br />

serted too far (Fig. 1), was corrected accord<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

CXR by 1.5 cm (UVC) and cm (UAC). After receiv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

porc<strong>in</strong>e surfactant (Curosurf®), the <strong>in</strong>fant was success-<br />

fully weaned from mechanical ventilation. CXR before<br />

planned extubation on day three unexpectedly sho-<br />

wed cardiomegaly with a heart-to-lung ratio of 0.69<br />

(Fig. ). Echocardiography was performed immediate-<br />

ly and revealed a large echo-free pericardial effusion<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

CASE REPORT

DISCUSSION<br />

measur<strong>in</strong>g 6 mm <strong>in</strong> diameter (Fig. ). Both atrial and<br />

ventricular function were adequate, without diastolic<br />

<strong>in</strong>dentation of the atrial wall. The UVC tip was float<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the right atrium. On the X-ray, the UVC was still<br />

positioned too high project<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the cardiac silhou-<br />

ette (Fig. ), although its <strong>in</strong>itial position had been ade-<br />

quately corrected. Aspiration through the UVC yielded<br />

bloody fluid, and blood gas and chemical analysis of the<br />

aspirate were consistent with blood and not parenteral<br />

nutrition. Ultrasound exam<strong>in</strong>ation ruled out pleural and<br />

abdom<strong>in</strong>al effusions. Stool cultures of the <strong>in</strong>fant and<br />

the mother were negative for enterovirus. Maternal se-<br />

rologies were negative for TORCHS, Parvovirus B19, and<br />

Coxiella burnetii.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the <strong>in</strong>fant rema<strong>in</strong>ed hemodynamically stable with<br />

no signs of cardiovascular compromise, we decided<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st emergency pericardiocentesis. After remov<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the UVC, the effusion gradually resolved with<strong>in</strong> a few<br />

days, and the <strong>in</strong>fant was successfully extubated. The<br />

later cl<strong>in</strong>ical course was complicated by bronchopul-<br />

monary dysplasia and osteopathy of prematurity. Later<br />

cardiac follow-up revealed no functional or anatomical<br />

pathology.<br />

Pericardial effusion is a well-known complication of<br />

peripherally <strong>in</strong>serted central catheters (PICC), with an<br />

estimated <strong>in</strong>cidence of 1.8/1000 catheters ( ). The ma-<br />

jority of <strong>in</strong>fants with reported pericardial effusion beca-

5<br />

me acutely symptomatic due to cardiac tamponade and<br />

deteriorated rapidly with signs of respiratory distress,<br />

cyanosis, tachycardia or bradycardia, mottled sk<strong>in</strong>, and<br />

arterial hypotension f<strong>in</strong>ally lead<strong>in</strong>g to cardiopulmonary<br />

arrest not responsive to standard <strong>in</strong>terventions ( ). No-<br />

tably, approximately a quarter of the cases were first<br />

diagnosed post-mortem at autopsy ( ). The mortality is<br />

very high ( 5-65%) ( , ) and those resuscitated success-<br />

fully improved only <strong>after</strong> emergency pericardiocentesis<br />

was performed. Analysis of the aspirated liquid usually<br />

reflected the composition of the parenteral nutrition.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g a series of case reports on <strong>in</strong>fant deaths attri-<br />

buted to PICC-associated cardiac tamponade, guidel<strong>in</strong>es<br />

have been published aimed at reduc<strong>in</strong>g the risk of car-<br />

diac perforation ( -5).<br />

Contrary to PICC, the <strong>in</strong>cidence of pericardial effusion<br />

associated with UVC is unknown but case reports have<br />

documented sudden cardiovascular compromise <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<br />

fants with UVC due to pericardial tamponade (6-8).<br />

Perforation and catheter migration are thought to occur<br />

as a result of both mechanical pressure by the catheter<br />

tip repeatedly push<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the contract<strong>in</strong>g heart<br />

wall and endocardial <strong>in</strong>jury caused by hyperosmotic pa-<br />

renteral nutrition fluids. Transmural diffusion of paren-<br />

teral nutrition fluids <strong>in</strong>to the pericardial space further<br />

contributes to the accumulation of fluid. Contrary to<br />

catheter-associated <strong>in</strong>fections and thrombosis which<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease over time, pericardial effusion may occur directly

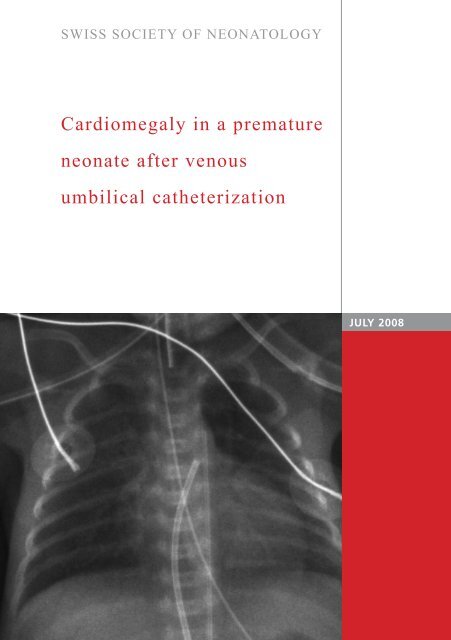

Fig. 1<br />

UVC<br />

UAC<br />

Chest X-ray on day one <strong>after</strong> <strong>in</strong>tubation and <strong>in</strong>sertion<br />

of <strong>venous</strong> (UVC) and arterial (UAC) <strong>umbilical</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

6

UVC<br />

UAC<br />

Incidental f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of cardiomegaly on chest X-ray<br />

before extubation on day three. UVC: <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

<strong>venous</strong> catheter; UAC: <strong>umbilical</strong> arterial catheter.<br />

Fig. 2

<strong>after</strong> <strong>in</strong>sertion of catheters, or later, with a peak at<br />

three days follow<strong>in</strong>g catheter <strong>in</strong>sertion ( ). Malposition<br />

of central catheters is considered the ma<strong>in</strong> risk factor<br />

for pericardial effusion, particularly if the catheter tip<br />

projects <strong>in</strong>to the right atrium or shows angulation ( ,<br />

). The catheter tip should be positioned at the junction<br />

of the vena cava <strong>in</strong>ferior and right atrium with the tip<br />

ly<strong>in</strong>g outside the cardiac silhouette. However, catheter<br />

<strong>in</strong>ward migration, as experienced <strong>in</strong> the present case,<br />

has been described and is attributed to retraction of<br />

the mummify<strong>in</strong>g cord, changes <strong>in</strong> abdom<strong>in</strong>al girth and<br />

catheter dislocation dur<strong>in</strong>g manipulations (6, 9). The-<br />

refore, even <strong>after</strong> correct <strong>in</strong>itial placement, the UVC<br />

position should be checked regularly us<strong>in</strong>g X-ray or<br />

ultrasound.<br />

The differential diagnosis of neonatal pericardial effu-<br />

sion <strong>in</strong>cludes immune and non-immune hydrops fetalis,<br />

congenital <strong>in</strong>fections such as TORCHS and Parvovirus<br />

B19, and rarely myopericarditis caused by Enteroviridae,<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly Echovirus and Cocksackievirus, or Coxiella burnetii.<br />

The present case illustrates that pericardial effusion<br />

may progress asymptomatically before hemodynamic<br />

changes become evident. The <strong>in</strong>cidence of catheter-asso-<br />

ciated pericardial effusion may therefore be underesti-<br />

mated. Extremely low birth-weight <strong>in</strong>fants might be at<br />

particular risk due to the th<strong>in</strong> myocardial wall with rela-<br />

tively large catheters often - as <strong>in</strong> this case - be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>i-<br />

tially <strong>in</strong>serted too far. Consider<strong>in</strong>g the potentially lethal<br />

8

9<br />

*<br />

*<br />

*<br />

Echocardiography demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g large pericardial<br />

effusion (asterisks) on day three.<br />

*<br />

Fig. 3

complications of UVC, neonatologists should carefully<br />

consider the <strong>in</strong>dication for plac<strong>in</strong>g UVCs and remove<br />

UVCs as soon as possible. Whether percutaneous long<br />

l<strong>in</strong>es represent a safer alternative rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear and<br />

further prospective studies compar<strong>in</strong>g UVC and PICC<br />

are needed (1). Mal-positioned UVCs should be cor-<br />

rected immediately and the position should be verified<br />

<strong>after</strong>wards. F<strong>in</strong>ally, neonatologists should ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a<br />

high <strong>in</strong>dex of suspicion for pericardial tamponade and<br />

readily perform echocardiography <strong>in</strong> acutely ill <strong>in</strong>fants<br />

with UVCs.<br />

In conclusion, pericardial effusion may occur asympto-<br />

matically <strong>after</strong> <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheterization and<br />

should be suspected <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with central catheters<br />

and progressive cardiomegaly. Prompt removal of ca-<br />

theters and, if signs of pericardial tamponade are pre-<br />

sent, emergency pericardiocentesis, may prove life-sav<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

For related cases, see also COTM 10/ 001 and COTM<br />

1 / 00 .<br />

10

11<br />

1. Butler-O‘Hara M, Buzzard CJ, Reubens L, McDermott MP,<br />

DiGrazio W, D‘Angio CT. A randomized trial compar<strong>in</strong>g<br />

long-term and short-term use of <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheters<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>premature</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with birth weights of less than<br />

1 51 grams. Pediatrics 006;118:e 5- 5<br />

. Beardsall K, White DK, P<strong>in</strong>to EM, Kelsall AW. Pericardial ef<br />

fusion and cardiac tamponade as complications of neonatal<br />

long l<strong>in</strong>es: are they really a problem? Arch Dis Child Fetal<br />

Neonatal Ed 00 ;88:F 9 - 95<br />

. Darl<strong>in</strong>g JC, Newell SJ, Mohamdee O, Uzun O, Cull<strong>in</strong>ane CJ,<br />

Dear PR. Central <strong>venous</strong> catheter tip <strong>in</strong> the right atrium: a risk<br />

factor for neonatal cardiac tamponade. J Per<strong>in</strong>atol 001;<br />

1: 61- 6<br />

. Nowlen TT, Rosenthal GL, Johnson GL, Tom DJ, Vargo TA.<br />

Pericardial effusion and tamponade <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants with central<br />

catheters. Pediatrics 00 ;110:1 -1<br />

5. Pezzati M, Filippi L, Chiti G, Dani C, Rossi S, Bert<strong>in</strong>i G,<br />

Rubaltelli FF. Central <strong>venous</strong> catheters and cardiac tamponade<br />

<strong>in</strong> preterm <strong>in</strong>fants. Intensive Care Med 00 ; 0: 5 - 56<br />

6. Traen M, Schepens E, Laroche S, van Overmeire B. Cardiac<br />

tamponade and pericardial effusion due to <strong>venous</strong> <strong>umbilical</strong><br />

catheterization. Acta Paediatr 005;9 :6 6-6 8<br />

. Sehgal A, Cook V, Dunn M. Pericardial effusion associated<br />

with an appropriately placed <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong> catheter.<br />

J Per<strong>in</strong>atol 00 ; : 1 - 19<br />

8. Onal EE, Saygili A, Koc E, Turkyilmaz C, Okumus N, Atalay Y.<br />

Cardiac tamponade <strong>in</strong> a newborn because of <strong>umbilical</strong> <strong>venous</strong><br />

catheterization: is correct position safe? Paediatr Anaesth<br />

00 ;1 :95 -956<br />

9. Salvadori S, Piva D, Filippone M. Umbilical <strong>venous</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

displacement as a consequence of abdom<strong>in</strong>al girth variation.<br />

J Pediatr 00 ;1 1:<br />

REFERENCES