Giving Peace an Address? - Berghof Handbook for Conflict ...

Giving Peace an Address? - Berghof Handbook for Conflict ...

Giving Peace an Address? - Berghof Handbook for Conflict ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

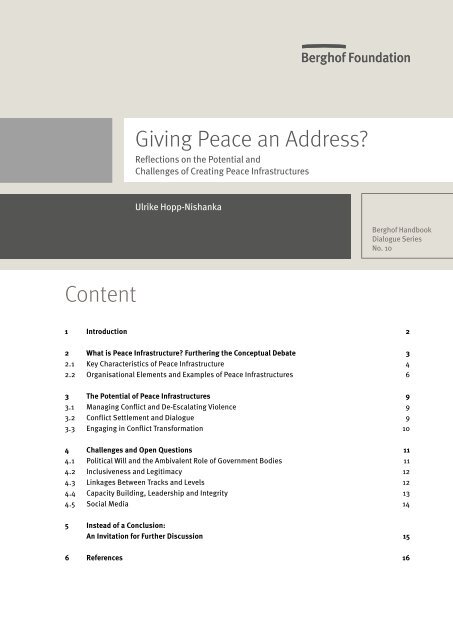

Content<br />

<strong>Giving</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Address</strong>?<br />

Reflections on the Potential <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Challenges of Creating <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures<br />

Ulrike Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka<br />

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook<br />

Dialogue Series<br />

No. 10<br />

1 Introduction 2<br />

2 What is <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure? Furthering the Conceptual Debate 3<br />

2.1 Key Characteristics of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure 4<br />

2.2 Org<strong>an</strong>isational Elements <strong>an</strong>d Examples of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures 6<br />

3 The Potential of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures 9<br />

3.1 M<strong>an</strong>aging <strong>Conflict</strong> <strong>an</strong>d De-Escalating Violence 9<br />

3.2 <strong>Conflict</strong> Settlement <strong>an</strong>d Dialogue 9<br />

3.3 Engaging in <strong>Conflict</strong> Tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation 10<br />

4 Challenges <strong>an</strong>d Open Questions 11<br />

4.1 Political Will <strong>an</strong>d the Ambivalent Role of Government Bodies 11<br />

4.2 Inclusiveness <strong>an</strong>d Legitimacy 12<br />

4.3 Linkages Between Tracks <strong>an</strong>d Levels 12<br />

4.4 Capacity Building, Leadership <strong>an</strong>d Integrity 13<br />

4.5 Social Media 14<br />

5 Instead of a Conclusion:<br />

An Invitation <strong>for</strong> Further Discussion 15<br />

6 References 16

About the <strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series:<br />

The Dialogue Series is <strong>an</strong> offshoot of the <strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook <strong>for</strong> <strong>Conflict</strong> Tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation. Each topic in<br />

the series is chosen because it is particularly relev<strong>an</strong>t to societies in conflict <strong>an</strong>d the practice of conflict<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation, <strong>an</strong>d because it raises import<strong>an</strong>t issues at the present time. In each Dialogue, practitioners<br />

<strong>an</strong>d scholars critically engage <strong>an</strong>d debate in light of their experience.<br />

Typically, a Dialogue includes one lead article from key experts, <strong>an</strong>d several commentaries from practitioners<br />

<strong>an</strong>d others. Rather th<strong>an</strong> presenting a single <strong>an</strong>alysis, these practitioner-scholar encounters stimulate<br />

debate, integrating different perspectives, challenging prevailing views <strong>an</strong>d comparing research findings<br />

with experiences <strong>an</strong>d insights on the ground. Import<strong>an</strong>tly, Dialogues, as works of broad relev<strong>an</strong>ce, are<br />

distributed in print version as well as online.<br />

We invite readers to respond to the papers (as to all articles). Interesting <strong>an</strong>d original contributions c<strong>an</strong> be<br />

added to the web version of the Dialogue.<br />

To <strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue No 10 <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures – Assessing Concept <strong>an</strong>d Practice the<br />

following authors have contributed:<br />

A Stina Lundström <strong>an</strong>d Barbara Unger (eds.) (introduction)<br />

A Ulrike Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka (lead article)<br />

A Oliver P. Richmond (response article)<br />

A H<strong>an</strong>nes Siebert (response article)<br />

A Borja Paladini Adell (response article)<br />

A Ulrike Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka (reflection on the responses)<br />

Acknowledgements:<br />

Layout & Graphics Design: Coxor<strong>an</strong>ge (http://coxor<strong>an</strong>ge-berlin.de/)<br />

Proofreading: Aaron Griffiths<br />

© 2012 <strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation Operations GmbH. All rights reserved.<br />

To cite this article: Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka, Ulrike, 2012. <strong>Giving</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Address</strong>? Reflections on the Potential <strong>an</strong>d Challenges of Creating <strong>Peace</strong><br />

Infrastructure, in: Barbara Unger, Stina Lundström, Katrin Pl<strong>an</strong>ta <strong>an</strong>d Beatrix Austin (eds). <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures – Assessing Concept <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Practice. <strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10. Berlin: <strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation. . First launch 30.11.2012. First launch 30.11.2012.<br />

Order at:<br />

<strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation<br />

Altensteinstraße 48a<br />

14195 Berlin, Germ<strong>an</strong>y<br />

Via Internet:<br />

www.berghof-h<strong>an</strong>dbook.net<br />

www.berghof-foundation.org<br />

order@berghof-foundation.org

1 Introduction 1<br />

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

In early 2007, community groups in suburbs of Tamale, the capital of the Northern Region of Gh<strong>an</strong>a,<br />

clashed over the construction of a water pipeline. Violence <strong>an</strong>d destruction ensued, local businesses shut<br />

down, the police had to intervene <strong>an</strong>d several community leaders <strong>an</strong>d youths were arrested. The violence,<br />

however, did not escalate further <strong>an</strong>d the conflict was settled outside court with the help of the Northern<br />

Region <strong>Peace</strong> Advisory Council, a group of more th<strong>an</strong> 20 civil society representatives, religious leaders<br />

<strong>an</strong>d local authority representatives (Dram<strong>an</strong> et al. 2009). Building on the trust <strong>an</strong>d accept<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>for</strong>ged with<br />

traditional chiefs, the group engaged in various <strong>for</strong>ms of dispute resolution around l<strong>an</strong>d, religion, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

social <strong>an</strong>d political issues, as well as community peacebuilding work. Similar stories are reported from all<br />

over Gh<strong>an</strong>a, <strong>an</strong>d their successes are related to the country’s national peace architecture that has evolved in<br />

recent years (<strong>for</strong> <strong>an</strong> overview see Ojielo 2007).<br />

What is special about the example from Gh<strong>an</strong>a is the contribution of government agencies. They<br />

play <strong>an</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t role in the peace ef<strong>for</strong>ts: the members of the advisory council did not come together<br />

on their own, but were appointed by the regional minister; they are supported by the government’s peace<br />

promotion officers; <strong>an</strong>d different regional <strong>an</strong>d district councils are coordinated by a national government<br />

unit. Ch<strong>an</strong>ge agents have been institutionalised throughout the government system of Gh<strong>an</strong>a (see Box 2<br />

below <strong>for</strong> more details).<br />

The Gh<strong>an</strong>ai<strong>an</strong> example seems at odds with m<strong>an</strong>y other peacebuilding experiences where government<br />

actors are far more marginal. The reluct<strong>an</strong>ce other actors feel about engaging them is partially explained<br />

by the complicated <strong>an</strong>d compromised role governments tend to play in intra-state conflict, where often the<br />

state has been captured by exclusionary elites, state power is abused, <strong>an</strong>d moderate actors excluded. In<br />

<strong>an</strong>y event, it is rare to find governments embracing ch<strong>an</strong>ge in the way seen in Gh<strong>an</strong>a.<br />

What c<strong>an</strong> be learned from the Gh<strong>an</strong>ai<strong>an</strong> example? How c<strong>an</strong> it (<strong>an</strong>d others like it) be described <strong>an</strong>d<br />

understood? What are the necessary elements of such national frameworks? C<strong>an</strong> they be implemented in<br />

<strong>an</strong>y country? How c<strong>an</strong> they be supported? These questions are now being explored in the context of the<br />

emerging concept of peace infrastructure.<br />

The idea of peace infrastructure is to develop mech<strong>an</strong>isms <strong>for</strong> cooperation among all relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders,<br />

including the government, by promoting cooperative problem-solving <strong>an</strong>d institutionalising a response<br />

mech<strong>an</strong>ism to violent conflict (v<strong>an</strong> Tongeren 2011a). The underst<strong>an</strong>ding that a dialogue process <strong>an</strong>d its<br />

underlying cooperative structure are mutually enh<strong>an</strong>cing is not new (e.g. Ropers 1995); the novel focus<br />

here is on the structure – the org<strong>an</strong>isation, connection <strong>an</strong>d interaction – of cooperative mech<strong>an</strong>isms. While<br />

other concepts emphasise synergistic collaboration between peacebuilding interventions, the focus here<br />

is on building the structural capacities of the conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d stakeholders. Ch<strong>an</strong>ging the “hearts <strong>an</strong>d<br />

minds” of conflict parties is not enough: org<strong>an</strong>isational <strong>an</strong>d structural capacities are required to achieve<br />

conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

In principle, peace infrastructure composed of diverse, interconnected org<strong>an</strong>isations at different<br />

levels c<strong>an</strong> give peace <strong>an</strong> address in a social l<strong>an</strong>dscape torn by violence. It may either act as a ch<strong>an</strong>ge agent<br />

itself, or provide the necessary space <strong>for</strong> such ch<strong>an</strong>ge agents.<br />

At the outset, I should note that I regard peace infrastructure as a concept that helps us underst<strong>an</strong>d<br />

the domestic, internal ef<strong>for</strong>ts in a conflict or fragile context to create or build on existing mech<strong>an</strong>isms<br />

<strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>isations that engage in reducing violence <strong>an</strong>d problem solving. The focus is less on the role of<br />

1 The author is grateful to Norbert Ropers, Barbara Unger <strong>an</strong>d Paul v<strong>an</strong> Tongeren <strong>for</strong> lively discussions, without which the<br />

conceptual development of peace infrastructures presented here would not have been possible. The concept has been further<br />

developed with the help of the <strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook editing team’s feedback.<br />

2

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

external assist<strong>an</strong>ce to support these peace infrastructures, although insights on capacity building <strong>an</strong>d<br />

other me<strong>an</strong>s of (external) support are offered “between the lines” (<strong>an</strong>d explicitly in Box 5).<br />

The aim of this article is to investigate the promise <strong>an</strong>d potential as well as the challenges of peace<br />

infrastructures. It will conceptualise peace infrastructure <strong>an</strong>d highlight some open questions.<br />

The following section defines the term, explores its conceptual background, <strong>an</strong>d offers a taxonomy of<br />

its possible elements <strong>an</strong>d <strong>for</strong>ms. In the third section, the concept is discussed with a view to establishing<br />

its potential <strong>for</strong> m<strong>an</strong>aging, settling <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>ming conflicts. The fourth section will, based on practical<br />

experiences, point to some challenges <strong>an</strong>d open questions. The fifth section will conclude <strong>an</strong>d suggest<br />

steps <strong>for</strong> developing the concept further.<br />

2 What is <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure?<br />

Furthering the Conceptual Debate<br />

If peace infrastructure gives peace <strong>an</strong> address, what does this place look like? It could be <strong>an</strong>ything from a<br />

rugged shed housing a local peace council in a remote South Americ<strong>an</strong> village, to the eleg<strong>an</strong>tly designed<br />

high-rise office of a national truth <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation commission in the capital of <strong>an</strong> Afric<strong>an</strong> country.<br />

Its org<strong>an</strong>isations could include a ministry dealing with peace <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation in Nepal, the office of a<br />

presidential advisor coordinating the peace process in the Philippines, or one of the m<strong>an</strong>y district peace<br />

committees in Kenya.<br />

All these different org<strong>an</strong>isations represent elements of peace infrastructure. They are parts of a “dynamic<br />

network of interdependent structures, mech<strong>an</strong>isms, resources, values, <strong>an</strong>d skills which, through dialogue<br />

<strong>an</strong>d consultation, contribute to conflict prevention <strong>an</strong>d peacebuilding in a society” (Kumar 2011, 385).<br />

While acknowledging the relev<strong>an</strong>ce of the process of peacebuilding in which the actors <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>isations<br />

in a network engage, the focus in this description as well as in the concept under development here is on<br />

the org<strong>an</strong>isational aspect of the network (see Box 1). 2<br />

This section offers a working definition, describes peace infrastructures along five key characteristics<br />

<strong>an</strong>d then presents several examples as illustrations.<br />

Box 1: The Emerging Concept of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure<br />

In recent years, several practitioners <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>isations have developed different terms <strong>an</strong>d concepts<br />

that concern the org<strong>an</strong>isation <strong>an</strong>d architecture of peacebuilding. While the terminology is not yet fully<br />

defined, the following differentiation emerges:<br />

“<strong>Peace</strong>building infrastructure” refers to international actors as well as the domestic governmental<br />

(judicial, legislative <strong>an</strong>d executive) <strong>an</strong>d non-governmental structures <strong>an</strong>d fin<strong>an</strong>cial system (Dress 2005).<br />

The similar term “peacebuilding architecture” denotes a more focused approach to strategically assessing<br />

<strong>an</strong>d designing solutions <strong>for</strong> violent conflict according to architectural principles (Reychler 2002).<br />

In contrast, the focus of “infrastructures <strong>for</strong> peace (I4P)” is on the org<strong>an</strong>isational elements <strong>an</strong>d<br />

linkages that <strong>for</strong>m domestic “mech<strong>an</strong>isms <strong>for</strong> co-operation among all relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders in<br />

2 “Org<strong>an</strong>isation” in this text refers to groups of individuals that are connected by common purpose <strong>an</strong>d rules <strong>for</strong> a division<br />

of labour that define structure, membership <strong>an</strong>d boundaries of the org<strong>an</strong>isation. “Institution” refers to the rules that guide<br />

behaviour <strong>an</strong>d ensure social order in a society.<br />

3

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

peacebuilding by promoting cooperative problem solving to conflicts <strong>an</strong>d institutionalizing the response<br />

mech<strong>an</strong>isms to conflicts in order to tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>m them. National, district, <strong>an</strong>d local peace councils are<br />

cornerstones of such <strong>an</strong> infrastructure”. This emphasises institutionalisation within a government<br />

administration (v<strong>an</strong> Tongeren 2011a, 400). 3<br />

The similar concept of “peace support structures” highlights the ownership by all conflict parties<br />

<strong>an</strong>d includes elements established by conflict parties other th<strong>an</strong> the government, including non-state<br />

armed groups. Building on experiences in accomp<strong>an</strong>ying Track 1 peace negotiations (<strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Conflict</strong> Studies 2008; Hopp 2010; Wils et al. 2006), this concept concentrates on individual<br />

org<strong>an</strong>isations <strong>an</strong>d capacity building <strong>an</strong>d support <strong>for</strong> the conflict parties involved in a peace or dialogue<br />

process (<strong>Berghof</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> Support 2010).<br />

Discussing elements of the I4P concept <strong>an</strong>d <strong>Berghof</strong>’s concept of peace support structures <strong>an</strong>d<br />

developing them further, this article uses the term “peace infrastructures” to embrace both discussions<br />

without imposing its own interpretation on others.<br />

Bringing different discussions together, I propose the following working definition:<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures consist of diverse domestic, inter-connected <strong>for</strong>ms of engagement between conflict<br />

parties <strong>an</strong>d other stakeholders. Their org<strong>an</strong>isational elements c<strong>an</strong> be established at all stages of peace <strong>an</strong>d<br />

dialogue processes, at all levels of society, <strong>an</strong>d with varying degrees of inclusion. The objective of peace<br />

infrastructure is to assist the parties (e.g. through capacity building or advice), the process (e.g. through<br />

mediation between the conflict parties or facilitation of public participation), or the implementation of<br />

process results (e.g. through monitoring <strong>an</strong>d coordination of agreement implementation).<br />

2.1 Key Characteristics of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructure c<strong>an</strong> take various org<strong>an</strong>isational shapes <strong>an</strong>d names depending on the cultural <strong>an</strong>d<br />

conflict context. The working definition entails five characteristics that help to describe <strong>an</strong>d categorise<br />

them in a less abstract way:<br />

1. A key characteristic of peace infrastructures is their domestic foundation. The focus is on domestic<br />

capacities, not those of the international community <strong>an</strong>d their peacebuilding architecture (as with, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, the UN <strong>Peace</strong>building Commission <strong>an</strong>d Fund or the ef<strong>for</strong>ts of establishing <strong>an</strong> Afric<strong>an</strong> regional<br />

peacebuilding architecture). Whereas internationally backed ceasefire monitoring or peacekeeping<br />

missions – or perhaps even international Groups of Friends – c<strong>an</strong> be supportive elements of peace<br />

infrastructures, they c<strong>an</strong>not represent the only element. 4<br />

2. <strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures are established during <strong>an</strong>y stage of peace <strong>an</strong>d dialogue processes, from the height of a<br />

violent conflict to the implementation <strong>an</strong>d monitoring of peace agreements. They could extend far into the postconflict<br />

period if incorporating tr<strong>an</strong>sitional justice <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation mech<strong>an</strong>isms: truth <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation<br />

commissions are a prominent example, but places of memory like memorials <strong>an</strong>d peace museums could<br />

also be components of peace infrastructures if they contribute towards creating a common future.<br />

Figure 1 provides <strong>an</strong> overview of possible org<strong>an</strong>isational <strong>for</strong>ms of peace infrastructure along the stages<br />

of conflict escalation. Any of them may be found in combination <strong>an</strong>d would not exclude others.<br />

3 V<strong>an</strong> Tongeren (2011a, 2011b) offers <strong>an</strong> overview of decisive moments in the development of the concept. He highlights how the<br />

concept found its way into official documents in the years 2002 to 2006.<br />

4 The concept is also not about networking among external peacebuilding actors, as <strong>for</strong> example outlined in Robert Ricigli<strong>an</strong>o’s<br />

networks of effective action (2003). While working groups <strong>an</strong>d other arr<strong>an</strong>gements of these actors will entertain close<br />

connections with a peace infrastructure, they do not constitute one on their own.<br />

4

Level of<br />

conflict<br />

escalation<br />

Early warning<br />

mech<strong>an</strong>isms,<br />

local peace<br />

councils<br />

Domestic ceasefi re monitoring missions<br />

Secretariats <strong>for</strong> peace negotiations,<br />

national dialogue plat<strong>for</strong>ms<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> department or peace ministry,<br />

peace commissions on all tracks<br />

Figure 1: Org<strong>an</strong>isational elements of peace infrastructure along conflict stages.<br />

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

All party conferences on reconciliation,<br />

national reconciliation commissions<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> museums, memorial sites<br />

3. Elements of peace infrastructure are found at all levels <strong>an</strong>d peacebuilding tracks <strong>an</strong>d show various<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms of integration:<br />

A Vertical integration between different tracks: engaging different societal levels (top, middle, grassroots)<br />

<strong>an</strong>d administrative units at local, district, regional <strong>an</strong>d national levels.<br />

A Horizontal integration within the tracks: by bringing together all local peace council activities, or by<br />

establishing a regional plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> consultation, collaboration <strong>an</strong>d coordination among stakeholders.<br />

A Consolidation at national government level: providing a legal foundation <strong>an</strong>d appropriate budget <strong>for</strong><br />

peace infrastructure; establishing a government department or ministry dedicated to peacebuilding<br />

<strong>an</strong>d providing guiding policy.<br />

This characteristic highlights the structured, systematic character of peace infrastructures <strong>an</strong>d distinguishes<br />

them from the “naturally evolved” peace constituencies found at different levels in a society (Lederach<br />

1996). This difference is also expressed through a high level of government involvement <strong>an</strong>d intragovernmental<br />

coherence that emphasises the commitment of the government to support peace ef<strong>for</strong>ts.<br />

Individual elements alone – <strong>for</strong> example local peace councils – do not constitute peace infrastructure.<br />

Successful examples from Nepal, Gh<strong>an</strong>a or Kenya bring various elements together, albeit in different ways.<br />

4. <strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures vary in terms of inclusion. Two <strong>for</strong>ms of inclusion c<strong>an</strong> be distinguished: those<br />

stakeholders who establish peace infrastructure <strong>an</strong>d decide its m<strong>an</strong>date <strong>an</strong>d functions will govern <strong>an</strong>d<br />

“own” its elements; others might be invited to participate in activities but without a governing role.<br />

Most peace infrastructures include at least one of the conflict parties. 5 Ideally, more th<strong>an</strong> one would be<br />

involved in establishing the peace infrastructure; the peace process in South Africa <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>y other places<br />

suggest that inclusivity is a precondition <strong>for</strong> effectiveness (Kelm<strong>an</strong> 1999; OECD 2007). This will often<br />

me<strong>an</strong> including non-state armed groups. Strengthening their capacities is often a requirement <strong>for</strong> their<br />

participation in peace processes <strong>an</strong>d contributes to reducing asymmetry in negotiations.<br />

Various combinations of inclusion <strong>an</strong>d participation c<strong>an</strong> be conceived. These c<strong>an</strong> r<strong>an</strong>ge from “conflict<br />

parties only” (often found in the context of peace negotiations – peace secretariats or working committees),<br />

to “government-civil society” (as in the case of consultative plat<strong>for</strong>ms), to “government-all stakeholders”<br />

(as found in peace departments or ministries), to “all-party <strong>for</strong>ums” (like local peace councils or truth <strong>an</strong>d<br />

5 This aspect distinguishes peace infrastructure from <strong>an</strong>ything established by civil society alone. The latter could be part of a<br />

peace infrastructure but do not suffice <strong>for</strong> infrastructure establishment.<br />

Time<br />

5

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

reconciliation conferences). 6 While the latter hardly achieve all-inclusiveness, they are at least plat<strong>for</strong>ms<br />

<strong>for</strong> multiple stakeholders, not just those engaged in violent conflict.<br />

5. The different elements of peace infrastructure c<strong>an</strong> serve various objectives <strong>an</strong>d functions, which<br />

include:<br />

A Capacity building, advisory services <strong>an</strong>d (internal) consultation <strong>for</strong> the conflict parties;<br />

A Communication, facilitation <strong>an</strong>d mediation between conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d with other stakeholders;<br />

A Implementation, monitoring <strong>an</strong>d coordination of activities agreed by the conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d other<br />

stakeholders.<br />

The three groups of functions represent increasing levels of collaboration between the conflict parties.<br />

Whereas the first function does not involve collaboration between the parties, the second one does:<br />

here, org<strong>an</strong>isations often serve as a go-between or a bridge-builder. The third group of functions shows<br />

the highest level of collaboration, when conflict parties work together to implement the results of peace<br />

agreements or monitor them jointly.<br />

2.2 Org<strong>an</strong>isational Elements <strong>an</strong>d Examples of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures<br />

Any peace infrastructure involves various org<strong>an</strong>isational elements depending on these five characteristics.<br />

The r<strong>an</strong>ge of possible org<strong>an</strong>isational elements c<strong>an</strong> be conceived according to the level of collaboration<br />

between the conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d stakeholders on the one h<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>an</strong>d the level of inclusive participation at the<br />

other. Figure 2 presents <strong>an</strong> overview.<br />

Level of<br />

inclusion<br />

in peace<br />

infrastructure<br />

Think t<strong>an</strong>ks<br />

Intra-party<br />

committees<br />

All-party conferences<br />

on reconciliation<br />

National steering<br />

committees on peacebuilding<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> secretariats<br />

Local peace councils<br />

Consultative<br />

dialogue plat<strong>for</strong>ms<br />

Org<strong>an</strong>ised<br />

backch<strong>an</strong>nel<br />

structures<br />

Public online<br />

plat<strong>for</strong>ms <strong>for</strong><br />

early warning<br />

Figure 2: Org<strong>an</strong>isational elements of peace infrastructure along axes of inclusion <strong>an</strong>d collaboration.<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> ministries<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> museums<br />

Domestic monitoring<br />

missions on ceasefire<br />

implementation<br />

Collaboration<br />

6 Not all parts of a peace infrastructure will necessarily be accessible to the public; some will involve a certain level of<br />

confidentiality.<br />

6

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

The horizontal axis of the graph represents levels of collaboration between the conflict parties. Elements<br />

with low levels of collaboration are to the left: examples include intra-party committees set up to prepare<br />

<strong>an</strong>d discuss negotiations or think t<strong>an</strong>ks closely affiliated with one side of the conflict. Elements with high<br />

levels of collaboration are further to the right, such as peace ministries tasked with implementing a peace<br />

agreement (where staff recruitment <strong>an</strong>d govern<strong>an</strong>ce of the ministry contributes to collaboration).<br />

The level of inclusiveness is represented on the vertical axis <strong>an</strong>d is independent of the level of<br />

collaboration. Thus, a very collaborative org<strong>an</strong>isation such as a joint monitoring mission between <strong>for</strong>merly<br />

warring parties might be relatively exclusive, whereas a public online plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> early warning c<strong>an</strong> invite<br />

the widest public participation.<br />

The levels of collaboration do not correspond with the stages of conflict in a linear sense. Collaborative<br />

peace infrastructures between different non-state stakeholders <strong>an</strong>d the government c<strong>an</strong> be active even in<br />

the early phase of latent conflict, <strong>for</strong> example in early warning mech<strong>an</strong>isms. Several of the Afric<strong>an</strong> peace<br />

infrastructures established in the context of elections include functions of monitoring violence <strong>an</strong>d early<br />

warning systems (<strong>for</strong> example in Gh<strong>an</strong>a, Ojielo 2007).<br />

While the figure serves to show the scope of different org<strong>an</strong>isational <strong>for</strong>ms, it is of course a simplification.<br />

Org<strong>an</strong>isations will evolve over time <strong>an</strong>d under the influence of different agendas. This c<strong>an</strong> happen when,<br />

<strong>for</strong> example, the government becomes involved in a local civil society peace plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>an</strong>d contributes to its<br />

<strong>for</strong>malisation, its diffusion to other districts, <strong>an</strong>d eventually to the development of a national policy: this<br />

was the case with the district development <strong>an</strong>d peace committees in Kenya inspired by a women’s initiative<br />

in the Wajir district that had been built through long-st<strong>an</strong>ding civil society networking ef<strong>for</strong>ts (Jenner/Abdi<br />

2000; Kut 2007; GPPAC 2010).<br />

This example of bottom-up peace infrastructure is similar to the earlier example of the national peace<br />

architecture <strong>for</strong> peace in Gh<strong>an</strong>a (see Box 2).<br />

Box 2: The Bottom-Up National Infrastructure <strong>for</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> in Gh<strong>an</strong>a<br />

Despite appearing comparatively peaceful in regional terms, Gh<strong>an</strong>a has seen m<strong>an</strong>y kinds of violent<br />

inter-ethnic conflict at the community level (Bomb<strong>an</strong>de 2007). The first avenues <strong>for</strong> peacebuilding <strong>an</strong>d<br />

inter-ethnic reconciliation were opened by civil society initiatives in the 1990s, but fresh violence in<br />

2003 led to a more concerted peacebuilding ef<strong>for</strong>t by the government. Building on the experiences of<br />

<strong>an</strong> all-party advisory council in the crisis-prone Northern Region – a council that intervened in local<br />

conflicts to prevent violence <strong>an</strong>d find dispute resolution mech<strong>an</strong>isms suitable to the cultural context<br />

– a national infrastructure was established under the lead of the Ministry of Interior with assist<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

of UNDP (Ojielo 2007).<br />

The infrastructure comprises: peace advisory councils on the district, regional <strong>an</strong>d national level;<br />

government-affiliated peace promotion officers on the regional <strong>an</strong>d district level; <strong>an</strong>d a <strong>Peace</strong>building<br />

Support Unit within the Ministry of Interior (Ministry of the Interior 2006). There are varying levels of<br />

implementation across Gh<strong>an</strong>a’s 10 regions <strong>an</strong>d 138 districts, but observers note that it contributed<br />

signific<strong>an</strong>tly to the containment of tension <strong>an</strong>d prevention of violence during the 2008 national elections.<br />

The National <strong>Peace</strong> Council helped mediate the political tr<strong>an</strong>sition (Kumar 2011). The example of Gh<strong>an</strong>a<br />

has inspired other countries like Togo to consider similar arr<strong>an</strong>gements.<br />

In other cases, peace infrastructure builds on commitment at the central government level <strong>an</strong>d thus c<strong>an</strong><br />

be considered top-down. Examples are the peace infrastructures in Central Americ<strong>an</strong> countries which are<br />

based on the regional Esquipulas Process in the 1980s (Box 3), <strong>an</strong>d the peace infrastructure that serves to<br />

implement Nepal’s Comprehensive <strong>Peace</strong> Agreement (Box 4).<br />

7

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

Box 3: Diverse <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures Based on the Esquipulas Process in Central America<br />

To encourage national reconciliation processes in Nicaragua, Guatemala <strong>an</strong>d El Salvador <strong>an</strong>d to help<br />

stabilise the region without US armed intervention, a group of Central Americ<strong>an</strong> heads of state started<br />

a regional mediation process in the 1980s. While the original ef<strong>for</strong>t eventually failed, it helped to lay<br />

the foundation <strong>for</strong> later peace agreements <strong>an</strong>d each country subsequently developed a national peace<br />

infrastructure adapted to their own situation. In all cases, this included a national consultation process<br />

involving the government, armed groups <strong>an</strong>d the civil society.<br />

The process, although built “from the top down to the people” <strong>an</strong>d embedded in strong regional <strong>an</strong>d<br />

UN involvement, went beyond negotiations between the conflict parties only <strong>an</strong>d integrated consensus<br />

building on the grassroots level. As illustrated in the case of Nicaragua (Wehr/Lederach 1991), so-called<br />

“insider partials” as well as external mediators contributed to this process <strong>an</strong>d helped build trust.<br />

Each of the countries followed their own protracted process towards a peace agreement, or several<br />

agreements. In Nicaragua, separate agreements <strong>for</strong> the different conflicts were negotiated <strong>an</strong>d supported<br />

by separate structures including local <strong>an</strong>d regional peace commissions (<strong>for</strong> <strong>an</strong> overview see Odendaal<br />

2010). In Guatemala, a number of structures were installed at the national level to support the negotiations,<br />

monitor implementation <strong>an</strong>d coordinate civil society participation. Some complemented each other <strong>an</strong>d<br />

some did not. The government appointed its own structures <strong>for</strong> the negotiations; a parallel Civil Society<br />

Assembly was established to allow the public to participate in the peace process, although it was criticised<br />

in terms of the undue influence of the business sector (Armon et al. 1997; Sarti/Schünem<strong>an</strong>n 2011).<br />

Box 4: Central Government Ministry as Cornerstone of the <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure in Nepal<br />

The peace infrastructure in Nepal was established with the purpose of supporting the Comprehensive<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> Agreement of 2006 after years of armed conflict between the government <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> armed insurgency<br />

led by the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). The government’s peace ef<strong>for</strong>ts centre on the Ministry<br />

of <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Reconstruction that emerged out of the government peace secretariat after the peace<br />

agreement was reached. The ministry carries broad functions in monitoring <strong>an</strong>d implementing the peace<br />

accord <strong>an</strong>d is expected to support a wide r<strong>an</strong>ge of elements, including local peace committees with<br />

representatives from all societal stakeholders, a peace fund, a truth <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation commission, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

a commission to investigate disappear<strong>an</strong>ces (Ministry <strong>for</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Reconstruction of the Government<br />

of Nepal, n.d.).<br />

The infrastructure reflects the government’s commitment to a comprehensive peace process that<br />

would not end with a peace agreement. The local peace councils were established to link the Track 1<br />

peace process systematically to the grassroots level (Odendaal/Olivier 2008). However, centralisation<br />

<strong>an</strong>d domination by political elites limit inclusion <strong>an</strong>d responsiveness to local concerns (Dahal/Ch<strong>an</strong>dra<br />

2008). Civil society plays a key role in engaging the government as a partner <strong>an</strong>d in monitoring the<br />

conflict parties’ commitment to the peace accord (Thapa 2007).<br />

Moreover, the infrastructure shows the weaknesses of <strong>an</strong> artificial design that did not grow out of<br />

the local political cultural context. Some of the elements of the infrastructure have not been established<br />

yet <strong>an</strong>d, as Ram Bh<strong>an</strong>dari notes, the concept <strong>for</strong> the local peace infrastructure was “never discussed<br />

with local actors, but was designed from the top down, based on political negotiation <strong>an</strong>d donors’<br />

recommendations” (Bh<strong>an</strong>dari 2011, 15).<br />

The common feature of these very different peace infrastructures, bottom-up or top-down, is that they were<br />

established, developed <strong>an</strong>d maintained with the intention of furthering the peace <strong>an</strong>d dialogue process.<br />

Although some originate from specific community experiments, peace infrastructures are more th<strong>an</strong> the<br />

org<strong>an</strong>isations that evolve from political processes in a given conflict situation. They consist of a demarcated set<br />

8

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

of org<strong>an</strong>isations: a designated subsystem <strong>for</strong> peace within the overall conflict system. This delineation appears<br />

necessary. If everything is part of peace infrastructure, the concept becomes too holistic <strong>an</strong>d loses traction.<br />

The discussion so far has put <strong>for</strong>th a working definition; it has shown that peace infrastructures c<strong>an</strong> take<br />

m<strong>an</strong>y different shapes <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong> ch<strong>an</strong>ge over the course of time. In their ideal <strong>for</strong>m, they represent inclusive<br />

<strong>an</strong>d sustained ef<strong>for</strong>ts of the conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d other relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders at preventing <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

conflict, building peace, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>for</strong>ging strong linkages between peacebuilding tracks; <strong>an</strong>d finally they imply<br />

<strong>an</strong> empowering, but not overpowering, commitment from the government. According to this vision,<br />

they have the potential to strengthen a given peace process by giving it <strong>an</strong> org<strong>an</strong>isational structure. The<br />

following section will discuss this potential in relation to three distinct areas.<br />

3 The Potential of <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructures<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures could be conceived as contributing to peacebuilding in three ways:<br />

1. Dealing with violence through conflict m<strong>an</strong>agement, violence containment or de-escalation;<br />

2. Dealing with the process of conflict settlement, <strong>for</strong> example through negotiations <strong>an</strong>d dialogue; <strong>an</strong>d<br />

3. Dealing with the structural causes <strong>an</strong>d the need <strong>for</strong> systemic tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

The three areas often overlap, but <strong>for</strong> conceptual purposes the distinction is maintained here.<br />

3.1 M<strong>an</strong>aging <strong>Conflict</strong> <strong>an</strong>d De-Escalating Violence<br />

Early warning mech<strong>an</strong>isms <strong>an</strong>d mech<strong>an</strong>isms to monitor <strong>an</strong>d implement ceasefires <strong>an</strong>d peace agreements<br />

are examples of peace infrastructure that c<strong>an</strong> potentially help to m<strong>an</strong>age conflict <strong>an</strong>d de-escalate violence.<br />

Other kinds of peace infrastructure c<strong>an</strong> potentially increase cooperative behaviour at the community level,<br />

<strong>for</strong> example in the context of elections. Org<strong>an</strong>isations working at Track 3, <strong>for</strong> inst<strong>an</strong>ce, c<strong>an</strong> help resolve<br />

community conflict at <strong>an</strong> early stage with the help of locally trusted mediators; they c<strong>an</strong> also alert actors<br />

at other societal levels in order to increase security in a local environment, coordinate intervention with<br />

others, or liaise with neighbouring district level bodies (IRIN 2010b).<br />

With a view to fragile situations, peace infrastructure could potentially help increase government<br />

legitimacy, enh<strong>an</strong>cing their accountability <strong>an</strong>d building public trust <strong>an</strong>d confidence in state institutions. By<br />

being part of the peace infrastructure, government bodies <strong>an</strong>d their staff c<strong>an</strong> engage in joint problem-solving<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d less hierarchical, asymmetric relations th<strong>an</strong> in their usual bureaucratic environment. Recognising<br />

these ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d their potential contribution to security as well as development, the latest World Development<br />

Report features examples of infrastructures <strong>for</strong> conflict prevention <strong>an</strong>d risk reduction (World B<strong>an</strong>k 2011,<br />

188-189).<br />

3.2 <strong>Conflict</strong> Settlement <strong>an</strong>d Dialogue<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures reflect a growing domestic ownership of peacebuilding <strong>an</strong>d a commitment to building<br />

internal capacities <strong>for</strong> conflict settlement (Kumar 2011). While external support in <strong>for</strong>m of mediation is<br />

often indispensable, domestic peace infrastructure c<strong>an</strong> be complementary. <strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures are of<br />

particular relev<strong>an</strong>ce in situations without a sufficient internal political consensus <strong>for</strong> external mediation,<br />

or where violence is too dispersed to be dealt with through centralised external mediation.<br />

In this capacity, peace infrastructure provides a space or a <strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> dialogue along different tracks.<br />

In situations of political tr<strong>an</strong>sition <strong>an</strong>d regime ch<strong>an</strong>ge, domestic institutions might convene national<br />

dialogue or negotiations about governing arr<strong>an</strong>gements. An example is found in Leb<strong>an</strong>on where a<br />

9

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

presidential initiative to create national unity <strong>an</strong>d work towards reconciliation is combined with providing<br />

expertise to stakeholders, combining facilitation <strong>an</strong>d capacity building (Common Space Initiative 2011).<br />

When accomp<strong>an</strong>ying external Track 1 mediation, peace infrastructure c<strong>an</strong> help to broaden the foundation <strong>for</strong><br />

negotiations by involving the other tracks, like the One-Text-Initiative in Sri L<strong>an</strong>ka that works on Track 1.5 <strong>an</strong>d<br />

reaches out to the grassroots level by connecting to local people’s <strong>for</strong>ums (Siebert 2007; Timberm<strong>an</strong> 2007).<br />

In certain situations, structures within peace infrastructures c<strong>an</strong> also per<strong>for</strong>m the function of facilitation<br />

if serving as, or assisting, “insider mediators” (Mason 2009). Being close to the conflict parties, these mostly<br />

individual actors engage in mediation ef<strong>for</strong>ts, often adding credibility <strong>an</strong>d trust to the process as they are<br />

more invested in it <strong>an</strong>d more knowledgeable about it th<strong>an</strong> outsiders. Supported by the peace infrastructure,<br />

they c<strong>an</strong> establish a “plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> ch<strong>an</strong>ge”, which in Paul v<strong>an</strong> Tongeren’s words is “a functional network<br />

that would sp<strong>an</strong> across the divisions <strong>an</strong>d levels of society <strong>an</strong>d that would ensure optimum collaboration<br />

between the main stakeholders” (v<strong>an</strong> Tongeren 2011a, 401 referring to Lederach 2005).<br />

With a view to the content of negotiations <strong>an</strong>d dialogue, community-based peace infrastructures c<strong>an</strong><br />

provide Track 1 actors with insights into the situation on the ground <strong>an</strong>d help shape proposals. This could<br />

add a collaborative, integrative perspective – rooted characteristically in joint problem-solving approaches<br />

– to the negotiations <strong>an</strong>d counterbal<strong>an</strong>ce the usual orientation towards bargaining strategies. Think t<strong>an</strong>ks<br />

<strong>an</strong>d other org<strong>an</strong>isations that offer policy advice at Track 1 or 2 provide other ways to strengthen negotiation<br />

<strong>an</strong>d dialogue capacities. Examples include the Palestine Negotiation Support Unit, the peace secretariats<br />

of the government <strong>an</strong>d the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Sri L<strong>an</strong>ka, the Nepal Tr<strong>an</strong>sition to <strong>Peace</strong><br />

Initiative, <strong>an</strong>d the Common Space Initiative in Leb<strong>an</strong>on (Walton 2011).<br />

3.3 Engaging in <strong>Conflict</strong> Tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

By building the capacities of conflict parties <strong>an</strong>d encouraging their active involvement in peace processes<br />

<strong>an</strong>d other <strong>for</strong>ms of dialogue, peace infrastructures c<strong>an</strong> be said to play a role in conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Ideally, they bring together stakeholders <strong>an</strong>d their constituencies, ch<strong>an</strong>ge agents <strong>an</strong>d other parts of society<br />

<strong>an</strong>d provide the space <strong>for</strong> joint problem-solving, <strong>an</strong>d they c<strong>an</strong> help create, consolidate <strong>an</strong>d maintain a<br />

network of tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative actors. As Chet<strong>an</strong> Kumar (2011) points out, domestic infrastructures might be<br />

more import<strong>an</strong>t th<strong>an</strong> external mediation in m<strong>an</strong>y kinds of conflict situation, including in continuous,<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative or even revolutionary processes such as those witnessed in the “Arab Spring”.<br />

Local peace commissions present one of the few examples of domestic conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation org<strong>an</strong>isations<br />

rigorously discussed in existing literature. 7 These comprise <strong>an</strong>y “inclusive <strong>for</strong>um operating at sub-national<br />

level” that works with methods of “dialogue, promotion of mutual underst<strong>an</strong>ding <strong>an</strong>d trustbuilding, as well as<br />

inclusive, constructive problem-solving <strong>an</strong>d joint action to prevent violence” (Odendaal 2010, 3).<br />

The literature on conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation identifies a r<strong>an</strong>ge of possible contributions to the<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation of conflict actors, issues, <strong>an</strong>d structures (Miall 2004). Building trust <strong>an</strong>d improving<br />

relationships between the conflict parties lead to potential actor tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation as well as personal<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation. Knowledge tr<strong>an</strong>sfer <strong>an</strong>d capacity building potentially lead to issue tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation if they<br />

help find compromise, or to actor tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation if it contributes to a ch<strong>an</strong>ge of goals of a conflict party.<br />

Institution building c<strong>an</strong> lead to structure tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation when affecting the asymmetric power bal<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

between the conflict parties. The example of Gh<strong>an</strong>a, where institution building, reconciliation ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d<br />

7 The <strong>an</strong>alysis of conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation actors mostly centres on civil society actors <strong>an</strong>d non-governmental org<strong>an</strong>isations. The<br />

role of the conflict parties is seen as either that of spoilers or that of insider-partials <strong>an</strong>d ch<strong>an</strong>ge agents within the parties.<br />

These, however, are mostly described as individuals or groups of persons (e.g. Mason 2009). The role of org<strong>an</strong>isations is hardly<br />

discussed; one exception at the grassroots <strong>an</strong>d middle level of society are peace commissions (Lederach 1997, 2001), or, as<br />

other authors prefer, local peace <strong>for</strong>ums (Odendaal 2010).<br />

10

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

working towards a culture of dialogue come together, indicates several avenues of conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

(Ojielo 2007).<br />

This brief discussion has established the possible contributions of peace infrastructure in the areas of<br />

conflict m<strong>an</strong>agement, conflict settlement <strong>an</strong>d conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation. While this potential – derived from<br />

the literature <strong>an</strong>d individual cases – appears promising <strong>an</strong>d is attracting interest among donors <strong>an</strong>d thirdparty<br />

actors, more comparative evidence needs to be collected to consolidate the conceptual promise. To<br />

this end, the following section presents challenges <strong>an</strong>d open questions.<br />

4 Challenges <strong>an</strong>d Open Questions<br />

Literature on peace infrastructures <strong>an</strong>d their role <strong>an</strong>d impact in peace <strong>an</strong>d dialogue processes is still<br />

scarce. Existing reviews are mostly limited to evaluations of external support to the peace infrastructure;<br />

those concerning Track 1 (<strong>an</strong>d 1.5) often remain confidential. References in academic literature usually<br />

serve illustrative purposes <strong>an</strong>d are <strong>an</strong>ecdotal in character. Very few documents offer detailed accounts of<br />

the activities or the org<strong>an</strong>isational design of peace infrastructures.<br />

One noteworthy exception is the case of the peace infrastructure in South Africa. A cornerstone of<br />

the National <strong>Peace</strong> Accord, it is relatively well documented within the vast literature on the South Afric<strong>an</strong><br />

process (<strong>for</strong> example Gastrow 1995; Marks 2000; Spies 2002). Building on these experiences, Andries<br />

Odendaal is developing a growing body of comparative work on local peace <strong>for</strong>ums <strong>an</strong>d committees,<br />

elements of peace infrastructure at the local level (2011, 2010, 2006; Odendaal/Olivier 2008). Finally, the<br />

<strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation has collected material on 20 cases of Track 1 peace infrastructure org<strong>an</strong>isations.<br />

The remainder of this section, based on a review of this literature, raises five general themes. It offers<br />

“food <strong>for</strong> thought” <strong>an</strong>d discussion rather th<strong>an</strong> a comprehensive overview; further examination is needed.<br />

4.1 Political Will <strong>an</strong>d the Ambivalent Role of Government Bodies<br />

The <strong>for</strong>emost theme in literature concerning peace infrastructures concerns the ambivalent role of<br />

government bodies <strong>an</strong>d the problem of dependence on the political will of the top-level leaders. Without <strong>an</strong><br />

official m<strong>an</strong>date from the government, a community-based consultation process will remain a civil society<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>t that does not filter up to the national level. Without the political commitment of the conflict parties,<br />

Track 1 (or 1.5) dialogue processes may remain a mere facade or serve to contain domestic or international<br />

criticism (Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka <strong>for</strong>thcoming).<br />

In his review of local peace <strong>for</strong>ums in 12 different contexts, Odendaal (2010) shows that their effectiveness<br />

strongly depends on national-level commitment. Org<strong>an</strong>isations at the local level c<strong>an</strong>not override national<br />

political imperatives <strong>an</strong>d so remain vulnerable to “spoilers”. To deal with these challenges, they require a<br />

national-level m<strong>an</strong>date that makes them, paradoxically, even more vulnerable to political m<strong>an</strong>ipulation.<br />

Similar impressions c<strong>an</strong> be garnered from the Sri L<strong>an</strong>k<strong>an</strong> people’s <strong>for</strong>ums, which are active at the<br />

community level but seem not to have <strong>an</strong>y wider impact owing to the lack of government involvement or<br />

effective linkages to other tracks (Timberm<strong>an</strong> 2007). Government involvement, however, often leads to its<br />

domination of participatory processes <strong>an</strong>d politicisation (Brett et al. 2007; Rain<strong>for</strong>d/Satkun<strong>an</strong>ath<strong>an</strong> 2009).<br />

Political m<strong>an</strong>ipulation <strong>an</strong>d instrumentalisation may occur whenever one stakeholder has the power to<br />

dominate the design <strong>an</strong>d establishment of infrastructure. Moreover, tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative actors within existing<br />

infrastructure elements might not have sufficient space to contribute to the necessary ch<strong>an</strong>ge process. As<br />

Chet<strong>an</strong> Kumar notes, “where public or civic space is largely contested or polarized, widely trusted “ch<strong>an</strong>ge<br />

11

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

agents” or internal mediators may either be not available, or may not have the political space in which to<br />

facilitate the right conversations or behavioral ch<strong>an</strong>ge” (Kumar 2011, 387).<br />

Whether peace infrastructures remain effective appears to depend signific<strong>an</strong>tly on their “dependence”<br />

or level of politicisation. At worst, the peace infrastructure does not per<strong>for</strong>m its original functions <strong>an</strong>d<br />

becomes <strong>an</strong> empty shell, or is hijacked by those seeking to m<strong>an</strong>ipulate public opinion or international<br />

views or gain individual power. The key question is how such infrastructures c<strong>an</strong> move from being<br />

“mirrors” reflecting the destructive dynamics of the conflict towards being “incubators” that provide a safe<br />

space <strong>for</strong> sowing the seeds of tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative ch<strong>an</strong>ge.<br />

Involving a wider set of societal actors in establishing <strong>an</strong>d steering infrastructures might be one<br />

option; <strong>an</strong>other might be found in principles that guide, <strong>for</strong> example, the establishment of political think<br />

t<strong>an</strong>ks which are often gr<strong>an</strong>ted a certain level of intellectual independence from their leadership in order to<br />

do their job. <strong>Peace</strong> infrastructure may also need to have its own checks <strong>an</strong>d bal<strong>an</strong>ces through diverse actors<br />

<strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>isational <strong>for</strong>ms that complement <strong>an</strong>d correct each other.<br />

4.2 Inclusiveness <strong>an</strong>d Legitimacy<br />

Observations from various contexts show that, to be effective, peace infrastructure needs to be seen as<br />

legitimate by all relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders. To this end, inclusiveness is crucial – but un<strong>for</strong>tunately it is often<br />

unattainable, in particular in the early stages of peace processes. While infrastructure at the local level, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, might be able to mobilise communities to work together or increase the constructive commitment<br />

of influential stakeholders – businesspersons <strong>for</strong> example – they rarely m<strong>an</strong>age to integrate opposition<br />

hardliners.<br />

Some claim that peace infrastructure may sometimes need to be built without difficult stakeholders, <strong>for</strong><br />

example where so-called “spoilers” have the power to impede or paralyse their functioning <strong>an</strong>d where the<br />

org<strong>an</strong>isations have high visibility <strong>an</strong>d symbolic power. One case might be a complicated decision-making<br />

process on participation in initiatives to memorialise hum<strong>an</strong> rights violations <strong>an</strong>d the victims of violent<br />

conflict (Brett et al. 2007). Excluding relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders in such a process or emerging org<strong>an</strong>isation,<br />

however, usually hampers reconciliation <strong>an</strong>d might contribute to future conflict escalation.<br />

The challenge of inclusiveness <strong>an</strong>d legitimacy is not merely a matter of politics. On a technical level,<br />

it is also reflected in the question of who is represented in the govern<strong>an</strong>ce bodies of peace infrastructure.<br />

Studies of national-level org<strong>an</strong>isations as well as of local peace commissions from such diverse conflict<br />

contexts as South Africa, Kenya, Nepal, Sri L<strong>an</strong>ka or Macedonia show that inclusive staff composition is<br />

import<strong>an</strong>t (Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka <strong>for</strong>thcoming; Odendaal/Olivier 2008). Multi-partis<strong>an</strong> staff within org<strong>an</strong>isations<br />

provides <strong>an</strong> additional challenge <strong>for</strong> those dealing with conflict.<br />

Finally, the quest <strong>for</strong> inclusiveness also concerns the integration of marginalised perspectives, such as<br />

those of regional or ethnic minorities, poor <strong>an</strong>d low caste communities, women <strong>an</strong>d children, <strong>an</strong>d victims<br />

of hum<strong>an</strong> rights violations. In the case of recently established memorial sites in Peru, some of the decisionmaking<br />

processes do not sufficiently involve the relev<strong>an</strong>t local stakeholders <strong>an</strong>d concentrate too much on<br />

elites (Weissert 2012). Nepal’s local peace committees, although inclusive in theory <strong>an</strong>d designed to “address<br />

the concerns <strong>an</strong>d complaints of local stakeholders <strong>for</strong> democratic values, beliefs <strong>an</strong>d a sustainable peace”,<br />

have been criticised by locals as being dominated by political party ambitions <strong>an</strong>d as not considering the<br />

local population’s needs (Bh<strong>an</strong>dari 2011).<br />

4.3 Linkages Between Tracks <strong>an</strong>d Levels<br />

Most peace infrastructure requires connections between <strong>an</strong>d within societal levels (vertical <strong>an</strong>d horizontal<br />

links) in order to become effective. Multi-track engagement in peace infrastructures is often tr<strong>an</strong>slated into<br />

the sp<strong>an</strong>ning of all administrative units from the national level to local communities. The peace process in<br />

South Africa, <strong>for</strong> example, saw a coordinated ef<strong>for</strong>t to involve all levels, with distinct roles <strong>for</strong> each track.<br />

12

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

Here, as well as in Nicaragua, regional commissions helped in<strong>for</strong>m national peace ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d make them<br />

more effective. They did this by bringing in stakeholders with regional import<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d by communicating<br />

diverse local <strong>an</strong>d regional needs <strong>an</strong>d tr<strong>an</strong>slating them into national priorities (Marks 2000; Odendaal 2010).<br />

As with Track 2 engagement, regional capacities have <strong>an</strong> import<strong>an</strong>t role to play in terms of in<strong>for</strong>mation,<br />

coordination <strong>an</strong>d capacity building (Ojielo 2007).<br />

In reality, though, the sub-national, regional level is often the weak link between local <strong>an</strong>d national<br />

org<strong>an</strong>isations. The focus is usually either on local, grassroots ef<strong>for</strong>ts or on the national level, with<br />

regional activities regarded as mere tr<strong>an</strong>smission gears, neglected <strong>an</strong>d under-funded. In order to play a<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative role, the regional level needs strengthening. To this end, some peace infrastructures rely<br />

on a national “help desk” of sorts: a dedicated support unit, often installed within a government body,<br />

is established as the entry point <strong>for</strong> external capacity building <strong>an</strong>d coordinates the involvement of peace<br />

infrastructure with other government agencies. In Gh<strong>an</strong>a, this support has been org<strong>an</strong>ised by the Ministry<br />

of Interior which appointed regional <strong>Peace</strong> Promotion Officers based on nominations from the regional<br />

governments. The ministry provides further support through a <strong>Peace</strong>building Support Unit that coordinates<br />

with other government agencies (Ojielo 2007; Odendaal 2011).<br />

Such support, however, only fosters integration if there is willingness to engage all parts of society.<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructures often integrate different levels <strong>an</strong>d tracks on paper only. In practice, there may be<br />

severe capacity <strong>an</strong>d coordination constraints that limit the linkage to a one-way flow of in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Sometimes even this one-way communication is not a priority in political cultures dominated by elites. In<br />

such a situation, a national help desk alone will not address the underlying problems. 8<br />

4.4 Capacity Building, Leadership <strong>an</strong>d Integrity<br />

Setting aside the problem of how to enh<strong>an</strong>ce capacities if the will to use them is lacking, the question<br />

of how best to support emerging peace infrastructures remains. While adequate skills (technical skills,<br />

m<strong>an</strong>agement <strong>an</strong>d topical expertise) are necessary, org<strong>an</strong>isations within the peace infrastructure require<br />

more th<strong>an</strong> simply capacity building (see Box 5).<br />

Box 5: Options <strong>for</strong> Assisting <strong>Peace</strong> Infrastructure<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> infrastructure is attractive <strong>for</strong> donor <strong>an</strong>d other third-party assist<strong>an</strong>ce since it offers the opportunity<br />

to strengthen domestic capacities <strong>for</strong> peacebuilding. Assist<strong>an</strong>ce c<strong>an</strong> be provided in m<strong>an</strong>y ways: funding,<br />

capacity building, <strong>an</strong>d support <strong>for</strong> institution building c<strong>an</strong> make me<strong>an</strong>ingful contributions. Three<br />

recommendations emerge from the literature <strong>an</strong>d practical experiences:<br />

1. Assist<strong>an</strong>ce requires commitment from relev<strong>an</strong>t stakeholders <strong>an</strong>d ownership by beneficiaries<br />

The call to respect stakeholders’ ownership of ch<strong>an</strong>ge processes is often made, but experience shows it<br />

is difficult to achieve. Who needs to be involved at which stage when establishing peace infrastructure?<br />

How c<strong>an</strong> hardliners <strong>an</strong>d potential spoilers be dealt with? How to address marginalisation <strong>an</strong>d exclusion<br />

rooted in the political culture that might lead to the neglect of beneficiaries at the local level? These<br />

questions should be addressed not only among donors, but also with the main stakeholders <strong>an</strong>d the<br />

government.<br />

2. Capacity building should include strategic pl<strong>an</strong>ning <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>isational development needs<br />

An obvious area of support <strong>for</strong> peace infrastructure org<strong>an</strong>isations is capacity building on contentrelated<br />

issues. Negotiation <strong>an</strong>d mediation training or problem-solving workshops will be useful, but<br />

the org<strong>an</strong>isations also often need m<strong>an</strong>agement, pl<strong>an</strong>ning <strong>an</strong>d communication skills. Further, the<br />

tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative process that the org<strong>an</strong>isations are me<strong>an</strong>t to encourage often needs to start within the<br />

8 Parlevliet (2011) with a view to the state’s role in hum<strong>an</strong> rights <strong>an</strong>d conflict tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mation, argues <strong>for</strong> a differentiation of state<br />

capacity in ability (concerning technical skills) <strong>an</strong>d willingness (concerning values <strong>an</strong>d culture).<br />

13

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

infrastructure itself: accomp<strong>an</strong>ied org<strong>an</strong>isational development processes may be necessary in m<strong>an</strong>y<br />

peace infrastructures in order to come to terms with the effects of the violent conflict on their own<br />

org<strong>an</strong>isation <strong>an</strong>d its staff, as experiences in Sri L<strong>an</strong>ka show (<strong>Berghof</strong> Foundation <strong>for</strong> <strong>Conflict</strong> Studies<br />

2008; Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka <strong>for</strong>thcoming).<br />

3. Support needs to recognise its unintended consequences <strong>an</strong>d safeguard the legitimacy of peace<br />

infrastructures<br />

Problems with legitimacy may arise if external supporters take the lead in ushering their internal<br />

counterparts towards desired solutions. Not only might the peace infrastructure lack ownership,<br />

but the assist<strong>an</strong>ce might also cause harm if appearing biased towards one of the conflict parties.<br />

International (often western) approaches to establishing peace infrastructure might result in importing<br />

particular cultures of peace, memory <strong>an</strong>d reconciliation into a context in which they are <strong>for</strong>eign. And<br />

very practical issues might arise as well: the Palestine Negotiation Support Unit faced resentment when<br />

local stakeholders found the facilities <strong>an</strong>d salaries of the org<strong>an</strong>isation’s senior staff inappropriate<br />

(Milne/Black 2011).<br />

Beyond capacity building, two other org<strong>an</strong>isational ingredients appear necessary <strong>for</strong> establishing effective<br />

peace infrastructures: leadership <strong>an</strong>d institutional integrity.<br />

The personalities of political leaders <strong>an</strong>d senior staff matter crucially. Illustrative examples include<br />

the Central Americ<strong>an</strong> heads of state (Oscar Arias in particular) who shaped the Esquipulas process, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

the heads of the peace secretariats in the 2002 Sri L<strong>an</strong>k<strong>an</strong> peace process. Individual leaders <strong>for</strong>m <strong>an</strong>d<br />

in<strong>for</strong>m the infrastructures that they head (Hopp-Nish<strong>an</strong>ka <strong>for</strong>thcoming). The question is how c<strong>an</strong> the<br />

“right people” be brought into the job, <strong>an</strong>d who c<strong>an</strong> identify them?<br />

Very often, the nominations <strong>for</strong> leading administrative staff in political processes are politicised <strong>an</strong>d<br />

follow agendas other th<strong>an</strong> that of driving peaceful ch<strong>an</strong>ge processes. Internationally-assisted leadership<br />

development programmes like the ones in Burundi <strong>an</strong>d Timor Leste may be <strong>an</strong> effective way to engage <strong>an</strong>d<br />

indeed tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>m those leaders (Odendaal 2011).<br />

Another option concerns the recruitment of “insider mediators” as leaders. If they bring with them a<br />

personal commitment to peacebuilding, international experience, good connections with civil society <strong>an</strong>d<br />

a reputation <strong>for</strong> neutrality or multi-partiality, they could be the right choice <strong>for</strong> the job. On the other h<strong>an</strong>d,<br />

it could be argued that they should stay on the outside in order to maintain their independence <strong>an</strong>d serve<br />

the infrastructure as facilitators.<br />

Personal leadership alone is not sufficient. Research on the role of leadership in ch<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>an</strong>d<br />

development processes points to the need <strong>for</strong> “institutional integrity”. Such institutional integrity occurs<br />

when “the institutional arr<strong>an</strong>gements sustain the integrity of its personnel <strong>an</strong>d its processes <strong>an</strong>d – crucially<br />

– when the personnel <strong>an</strong>d processes sustain the institutions because they perceive it to be both legitimate<br />

<strong>an</strong>d effective” (Leftwich 2009). In other words, in order to be effective, leaders with tr<strong>an</strong>s<strong>for</strong>mative skills<br />

require a dem<strong>an</strong>d <strong>for</strong> their contribution in <strong>an</strong> org<strong>an</strong>isational l<strong>an</strong>dscape often in<strong>for</strong>med by violence, abuse<br />

of power, <strong>an</strong>d patronage.<br />

4.5 Social Media<br />

The final aspect to be discussed here concerns the use of social media <strong>for</strong> peace infrastructures <strong>an</strong>d its<br />

potential to overcome some of the limitations <strong>an</strong>d challenges discussed above. Social media technologies<br />

appear to be widely used in m<strong>an</strong>y of the recently developed peace infrastructures around the world,<br />

although their use has barely begun to be discussed.<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation technology is often applied in preventing <strong>an</strong>d responding to crises. Government agencies<br />

<strong>an</strong>d civil society, <strong>for</strong> example, collaborate <strong>an</strong>d collect early warning data <strong>an</strong>d provide crisis mapping<br />

through crowd sourcing (McConnell/Tsuma 2011). NGOs <strong>an</strong>d local peace councils send violence alerts via<br />

14

<strong>Berghof</strong> H<strong>an</strong>dbook Dialogue Series No. 10<br />

Twitter. This mobilises local in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>an</strong>d helps prepare crisis interventions, as the relatively peaceful<br />

conduct of the national referendum in Kenya in 2010 illustrates (IRIN 2010a). These activities improve<br />

conflict <strong>an</strong>alysis <strong>an</strong>d monitoring systems but in addition add a new dimension of public participation <strong>an</strong>d<br />

ownership to the society’s response to violence.<br />

Some org<strong>an</strong>isations use the Internet in order to share in<strong>for</strong>mation, viewpoints <strong>an</strong>d invite dialogue. For<br />

example, peace secretariats increase outreach <strong>an</strong>d public participation via Facebook; Track 1.5 initiatives<br />

facilitate web-based dialogue among stakeholders; <strong>an</strong>d some org<strong>an</strong>isations communicate within interestbased<br />

communities through Internet plat<strong>for</strong>ms <strong>an</strong>d discussion groups.<br />

While examples around the world are m<strong>an</strong>y, their effectiveness is not always clear (Stauffacher et al.<br />

2011; Timberm<strong>an</strong> 2007). Does the use of social media really help increase public participation <strong>an</strong>d overcome<br />

marginalisation? Does it create new lines of exclusion? In what ways are contributions from innumerable<br />

individual commentators processed, what gets lost, <strong>an</strong>d who decides?<br />

Sometimes the adoption of these technologies might simply follow a common trend regardless of their<br />

appropriateness or the requirements <strong>for</strong> their mainten<strong>an</strong>ce. Underst<strong>an</strong>ding the effectiveness of different<br />