Linke - Artinfo

Linke - Artinfo

Linke - Artinfo

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

84<br />

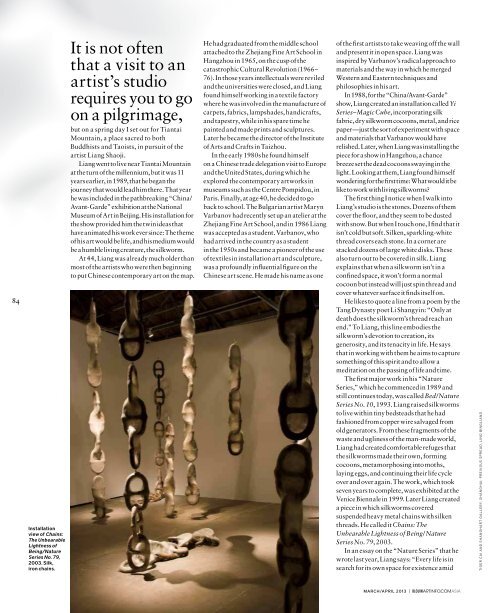

Installation<br />

view of Chains:<br />

The Unbearable<br />

Lightness of<br />

Being/Nature<br />

Series No. 79,<br />

2003. Silk,<br />

iron chains.<br />

It is not often<br />

that a visit to an<br />

artist’s studio<br />

requires you to go<br />

on a pilgrimage,<br />

but on a spring day I set out for Tiantai<br />

Mountain, a place sacred to both<br />

Buddhists and Taoists, in pursuit of the<br />

artist Liang Shaoji.<br />

Liang went to live near Tiantai Mountain<br />

at the turn of the millennium, but it was 11<br />

years earlier, in 1989, that he began the<br />

journey that would lead him there. That year<br />

he was included in the pathbreaking “China/<br />

Avant-Garde” exhibition at the National<br />

Museum of Art in Beijing. His installation for<br />

the show provided him the twin ideas that<br />

have animated his work ever since: The theme<br />

of his art would be life, and his medium would<br />

be a humble living creature, the silkworm.<br />

At 44, Liang was already much older than<br />

most of the artists who were then beginning<br />

to put Chinese contemporary art on the map.<br />

He had graduated from the middle school<br />

attached to the Zhejiang Fine Art School in<br />

Hangzhou in 1965, on the cusp of the<br />

catastrophic Cultural Revolution (1966–<br />

76). In those years intellectuals were reviled<br />

and the universities were closed, and Liang<br />

found himself working in a textile factory<br />

where he was involved in the manufacture of<br />

carpets, fabrics, lampshades, handicrafts,<br />

and tapestry, while in his spare time he<br />

painted and made prints and sculptures.<br />

Later he became the director of the Institute<br />

of Arts and Crafts in Taizhou.<br />

In the early 1980s he found himself<br />

on a Chinese trade delegation visit to Europe<br />

and the United States, during which he<br />

explored the contemporary artworks in<br />

museums such as the Centre Pompidou, in<br />

Paris. Finally, at age 40, he decided to go<br />

back to school. The Bulgarian artist Maryn<br />

Varbanov had recently set up an atelier at the<br />

Zhejiang Fine Art School, and in 1986 Liang<br />

was accepted as a student. Varbanov, who<br />

had arrived in the country as a student<br />

in the 1950s and became a pioneer of the use<br />

of textiles in installation art and sculpture,<br />

was a profoundly influential figure on the<br />

Chinese art scene. He made his name as one<br />

of the first artists to take weaving off the wall<br />

and present it in open space. Liang was<br />

inspired by Varbanov’s radical approach to<br />

materials and the way in which he merged<br />

Western and Eastern techniques and<br />

philosophies in his art.<br />

In 1988, for the “China/Avant-Garde”<br />

show, Liang created an installation called Yi<br />

Series–Magic Cube, incorporating silk<br />

fabric, dry silkworm cocoons, metal, and rice<br />

paper—just the sort of experiment with space<br />

and materials that Varbanov would have<br />

relished. Later, when Liang was installing the<br />

piece for a show in Hangzhou, a chance<br />

breeze set the dead cocoons swaying in the<br />

light. Looking at them, Liang found himself<br />

wondering for the first time: What would it be<br />

like to work with living silkworms?<br />

The first thing I notice when I walk into<br />

Liang’s studio is the stones. Dozens of them<br />

cover the floor, and they seem to be dusted<br />

with snow. But when I touch one, I find that it<br />

isn’t cold but soft. Silken, sparkling-white<br />

thread covers each stone. In a corner are<br />

stacked dozens of large white disks. These<br />

also turn out to be covered in silk. Liang<br />

explains that when a silkworm isn’t in a<br />

confined space, it won’t form a normal<br />

cocoon but instead will just spin thread and<br />

cover whatever surface it finds itself on.<br />

He likes to quote a line from a poem by the<br />

Tang Dynasty poet Li Shangyin: “Only at<br />

death does the silkworm’s thread reach an<br />

end.” To Liang, this line embodies the<br />

silkworm’s devotion to creation, its<br />

generosity, and its tenacity in life. He says<br />

that in working with them he aims to capture<br />

something of this spirit and to allow a<br />

meditation on the passing of life and time.<br />

The first major work in his “Nature<br />

Series,” which he commenced in 1989 and<br />

still continues today, was called Bed/Nature<br />

Series No. 10, 1993. Liang raised silkworms<br />

to live within tiny bedsteads that he had<br />

fashioned from copper wire salvaged from<br />

old generators. From these fragments of the<br />

waste and ugliness of the man-made world,<br />

Liang had created comfortable refuges that<br />

the silkworms made their own, forming<br />

cocoons, metamorphosing into moths,<br />

laying eggs, and continuing their life cycle<br />

over and over again. The work, which took<br />

seven years to complete, was exhibited at the<br />

Venice Biennale in 1999. Later Liang created<br />

a piece in which silkworms covered<br />

suspended heavy metal chains with silken<br />

threads. He called it Chains: The<br />

Unbearable Lightness of Being/ Nature<br />

Series No. 79, 2003.<br />

In an essay on the “Nature Series” that he<br />

wrote last year, Liang says: “Every life is in<br />

search for its own space for existence amid<br />

March/april 2013 | Blouin<strong>Artinfo</strong>.comAsiA<br />

tiger cai and Shanghart gallery, Shanghai; previouS S pread, ling bingliang<br />

Liang Shaoji and Shanghart ga LLery, S hanghai<br />

absurd and implacable contradictions. The<br />

strong silk threads, symbol of life, as if to<br />

break but resistant, show a strong will to life,<br />

an unremitting life pursuit, a force to beat<br />

the strong with softness, and life<br />

associations with endless extension.”<br />

By the time Bed/Nature Series No. 10 was<br />

complete, Liang had decided to move near<br />

Tiantai Mountain. It is home to the Tiantai<br />

sect of Buddhism, which Liang describes as<br />

the “most indigenous and most pristine” of<br />

all the Buddhist sects in China, and a place<br />

where over the centuries many “crazy<br />

monks” have gone to seek enlightenment.<br />

On Tiantai Mountain there is a platform<br />

where the founder of the sect, Zhiyi, is<br />

believed to have meditated. In 2007 Liang<br />

went there to make the film Cloud Mirror/<br />

Nature Series No. 101. Since moving to<br />

Tiantai he has become committed to the<br />

concept of the interconnectedness of living<br />

beings. Liang thinks this is embodied in the<br />

connection between silkworms and<br />

humankind, and between both of them and<br />

the rest of the natural world. In Cloud<br />

Mirror he illustrated this connection by<br />

holding up a mirror to the sky.<br />

On the mirrors Liang laid out on Tiantai<br />

Mountain, silkworms had already spun<br />

their silk in patterns that evoked the shapes<br />

of clouds. As real clouds passed overhead,<br />

they and the sky itself were reflected in<br />

Liang’s mirrors. In the video of the event,<br />

spun silk and clouds merge in the reflected<br />

sky until it is impossible to see where one<br />

ends and the other begins. The video is a<br />

poetic evocation of the passage of time, life,<br />

and the natural world.<br />

Liang likes to point out that in Chinese the<br />

words for poetry and for silk are homonyms,<br />

perhaps suggesting some deep cultural<br />

connection. He tells me that sericulture has<br />

existed in his country as long as the Chinese<br />

have claimed to have had a civilization,<br />

around 5,000 years. Taking the word<br />

associations further, he points out that the<br />

word for silkworm and the word for Zen also<br />

sound alike; in a 2006 work called Listening<br />

to the Silkworms, which he restaged at<br />

London’s Hayward Gallery last fall, he aims<br />

to induce a Zen-like state by inviting his<br />

audience to do exactly what the title suggests.<br />

The sound of silkworms eating mulberry<br />

leaves is remarkably like the bubbling of a<br />

running stream. In Listening to the<br />

Silkworms Liang asks visitors to sit in<br />

a darkened room and attend to the sounds of<br />

the silkworms’ life. What you hear is not a<br />

recording but silkworms living in an<br />

adjacent room in real time. And as you listen,<br />

you do begin to feel something of what Liang<br />

himself feels deeply, the profound<br />

Blouin<strong>Artinfo</strong>.comAsiA | march/april 2013<br />

connections that exist between everything<br />

in the natural world.<br />

In a catalogue essay for his exhibition “An<br />

Infinitely Fine Line” at Shanghai’s Zendai<br />

Museum of Modern Art, Liang wrote that<br />

“the entire ‘Nature Series’ is a sculpture of<br />

time, life, and nature, a recording of the<br />

fourth dimension.” Looking at the works,<br />

especially amid the ancient surroundings of<br />

Tiantai Mountain, you see what he is getting<br />

at. By working with silkworms he has<br />

consciously slowed his artistic practice to the<br />

pace of his tiny co-creators and connected<br />

his art to natural forces beyond his control.<br />

Liang calculates that he has raised around<br />

90,000 silkworms in the 23 years he has<br />

worked on the “Nature Series,” and estimates<br />

that the silk thread they have produced<br />

would wind around the world 10 times. One<br />

imagines he might try that someday.<br />

Detail of Bed/<br />

Nature Series<br />

No. 10, 1993–99.<br />

Charred copper<br />

wire, silk.