Disarmament and International Security - World Model United Nations

Disarmament and International Security - World Model United Nations

Disarmament and International Security - World Model United Nations

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

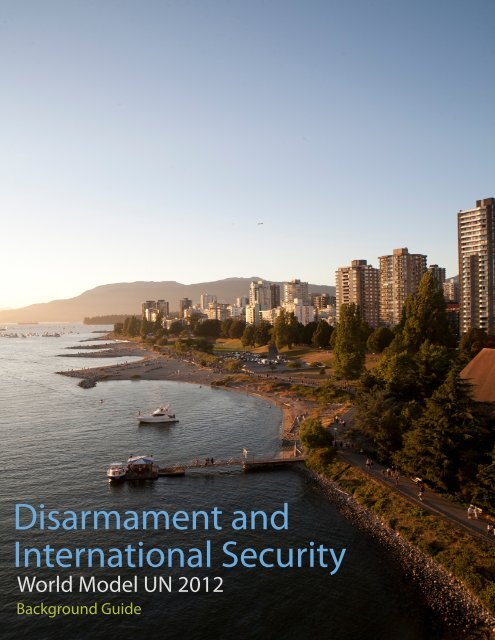

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong><br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Model</strong> UN 2012<br />

Background Guide

Letter from the Secretary General...............................................................................<br />

Letter from the Under-Secretary General....................................................................<br />

Letter from the Chair....................................................................................................<br />

Introduction..................................................................................................2<br />

History of the Committee...........................................................................................2<br />

Topic A:<br />

History <strong>and</strong> Discussion of the Problem...................................................................................3<br />

Current Situation....................................................................................................................10<br />

Past UN Actions......................................................................................................................14<br />

Proposed Solutions..................................................................................................................15<br />

Key Actors <strong>and</strong> Positions........................................................................................................16<br />

Relevant Partners....................................................................................................................19<br />

QARMA................................................................................................19<br />

Suggestions for Further Research............................................................................................20<br />

Topic B:<br />

History <strong>and</strong> Discussion of the Problem..............................................................................20<br />

Current Situation....................................................................................................................29<br />

Past UN Actions.....................................................................................................................30<br />

Proposed Solutions..................................................................................................................32<br />

Key Actors <strong>and</strong> Positions........................................................................................................34<br />

Relevant Partners....................................................................................................................36<br />

QARMA..............................................................................................36<br />

Suggestions for Further Research...........................................................................................37<br />

Position Papers.........................................................................................................37<br />

Closing Remarks.......................................................................................................37<br />

Bibliography................................................................................................46<br />

Cover image courtesy of Vancouver Tourism Board.<br />

Table of ConTenTs

KATHLEEN TANG<br />

Secretary-General<br />

SAMIR PATEL<br />

Director-General<br />

KEVIN LIU HUANG<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

General Assemblies<br />

ANNA TROWBRIDGE<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

for Economic <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Councils <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Bodies<br />

APARAJITA TRIPATHI<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

RICHARD EBRIGHT<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Operations<br />

SAMUEL LEITER<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Administration<br />

SCOTT YU<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Business<br />

Letter from the Secretary-General<br />

Dear Delegates,<br />

My name is Kathleen Tang <strong>and</strong> I am serving as the Secretary-<br />

General of the <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012 conference. After being a part<br />

of <strong>World</strong>MUN for the past few years it is a bittersweet experience<br />

to be running my last <strong>World</strong>MUN ever, but I could not be more<br />

excited to share this experience with all of you!<br />

Within the pages of this guide you will find the topics that the<br />

<strong>World</strong>MUN staff has been hard at work on over the past few<br />

months. Each chair worked hard to find a topic that they are truly<br />

passionate about <strong>and</strong> provide the best guides possible through<br />

extensive research. However, the background guide should<br />

only be the first step in your substantive learning process. Read<br />

through the guide thoroughly <strong>and</strong> note what areas of debate are<br />

particularly interesting for your chair <strong>and</strong> use this as a starting<br />

point for your own research on the topic. Remember that you<br />

will be representing a country, a people, <strong>and</strong> a culture outside of<br />

your own during your week of debate. What viewpoints does your<br />

country have on this topic? What would they say to the issues the<br />

chair brings up in the guide? In what ways would your country<br />

most like to see these issues ‘resolved’? There are always more<br />

sources to look at <strong>and</strong> more news to be up to date with so the<br />

learning never stops!<br />

Of course, if you ever need help along the way there are many<br />

resources up online for you - <strong>World</strong>MUN 101 <strong>and</strong> the Rules of<br />

Procedure are both up on our website (www.worldmun.org) <strong>and</strong><br />

will help you better underst<strong>and</strong> how to write a study guide <strong>and</strong><br />

how debate will run March 11-15th, 2012. Feel free to also reach<br />

out to your chair or USG via email. They are here to help you feel<br />

comfortable <strong>and</strong> prepared for the conference.<br />

I hope you enjoy the research presented here <strong>and</strong> also the learning<br />

process that comes with doing your own research on the topic.<br />

I look forward to meeting you in March!<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Kathleen Tang<br />

Secretary-General<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> 2012<br />

secretarygeneral@worldmun.org

KATHLEEN TANG<br />

Secretary-General<br />

SAMIR PATEL<br />

Director-General<br />

KEVIN LIU HUANG<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

General Assemblies<br />

ANNA TROWBRIDGE<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

for Economic <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Councils <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Bodies<br />

APARAJITA TRIPATHI<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

RICHARD EBRIGHT<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Operations<br />

SAMUEL LEITER<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Administration<br />

SCOTT YU<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Business<br />

Dear Delegates,<br />

It is my sincere pleasure to welcome you to the General Assemblies!<br />

You are joining the largest organ of the conference <strong>and</strong> the<br />

primary policymaking body of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>, where every<br />

nation is recognized as having an equal stake in the future of the<br />

world. The world has come a long way since the end of <strong>World</strong> War<br />

II; by gathering in such large numbers, the General Assemblies<br />

are a display of the international community’s seriousness <strong>and</strong><br />

commitment to solving world issues. Our conference, even if just<br />

a simulation, is a rare display of international unity about which I<br />

hope you are as delighted as I!<br />

My name is Kevin Liu Huang, <strong>and</strong> I am a junior at Harvard<br />

College, studying as a Government-Statistics double major. My<br />

home is a small town in New Jersey, where I grew up playing<br />

tennis <strong>and</strong> soccer <strong>and</strong> making weekend trips to New York City.<br />

At school, in addition to working Harvard’s many <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong><br />

<strong>Nations</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Congress simulations on campus, I also have<br />

taken up ballroom <strong>and</strong> Latin dancing.<br />

My job at this conference is to make your General Assembly<br />

experience as exhilarating <strong>and</strong> positive as possible. If you have<br />

any suggestions or complaints either throughout your conference<br />

experience or before it, feel free to get in touch with me directly<br />

or through your faculty advisor!<br />

Please feel free to connect with me through my e-mail! I am excited<br />

to serve as your Under-Secretary-General of General Assemblies<br />

for my very first Harvard <strong>World</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> conference,<br />

<strong>and</strong> I am looking forward to a conference like no other.<br />

See you in March!<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Kevin Liu Huang<br />

Under-Secretary-General of the<br />

General Assemblies<br />

ga@worldmun.org

KATHLEEN TANG<br />

Secretary-General<br />

SAMIR PATEL<br />

Director-General<br />

KEVIN LIU HUANG<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

General Assemblies<br />

ANNA TROWBRIDGE<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

for Economic <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Councils <strong>and</strong> Regional<br />

Bodies<br />

APARAJITA TRIPATHI<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

RICHARD EBRIGHT<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Operations<br />

SAMUEL LEITER<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Administration<br />

SCOTT YU<br />

Under-Secretary-General for<br />

Business<br />

Letter from the Chair<br />

Dear Delegates,<br />

It is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the <strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee at Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012.<br />

My name is Dominik Nieszporowski, <strong>and</strong> I am absolutely thrilled<br />

to be you committee chair during the fantastic week that you will<br />

spend in Vancouver next year, debating <strong>and</strong> learning from people<br />

from diverse backgrounds.<br />

Originally from Warsaw, Pol<strong>and</strong>, I have participated in <strong>Model</strong><br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> since high school, both as a delegate <strong>and</strong> committee<br />

chair at several conferences throughout Europe, Asia, <strong>and</strong> North<br />

America. My other passions include international development<br />

<strong>and</strong> public service – I have been particularly involved with<br />

programs creating educational opportunities for children in<br />

Africa.<br />

At Harvard, I am currently a senior in the glorious Kirkl<strong>and</strong><br />

House, concentrating in Applied Mathematics <strong>and</strong> Economics.<br />

On campus, I am mostly occupied serving as Secretary-General<br />

of Harvard National <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> 2012, an annual<br />

college <strong>Model</strong> UN conference held in Boston in February, <strong>and</strong><br />

coordinating HNMUN’s expansion abroad in the form of our new<br />

international conference – HNMUN Latin America 2012.<br />

This year at <strong>World</strong>MUN, DISEC will be debating two of the most<br />

important contemporary issues concerning international security<br />

– the militarization of the Arctic <strong>and</strong> the safeguarding of nuclear<br />

materials. As you embark on your research into these topics, I<br />

hope you will find them both interesting <strong>and</strong> thought-provoking.<br />

Please feel free to e-mail me to questions you might have or just to<br />

introduce yourself. I am certainly looking forward to an exciting<br />

debate <strong>and</strong> meeting many great people at <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012!<br />

Best regards,<br />

Dominik Nieszporowski<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong><br />

Committee

I n t r o d u c t I o n<br />

The <strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee,<br />

officially the First Committee of the General Assembly<br />

of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>, is one of the six main committees<br />

of the UNGA. The scope of DISEC’s competences <strong>and</strong> the<br />

significance of the issues it deals with – from security to<br />

international law – make it one of the most crucial organs of<br />

the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>.<br />

The topics that will be discussed at our session at <strong>World</strong>MUN<br />

2012 could serve as paragons of the caliber of the issues that<br />

the First Committee usually addresses. The problem of safety<br />

<strong>and</strong> security of nuclear materials is a relatively long-lasting<br />

concern that has recently gained some urgency due to a<br />

combination of several geopolitical factors in the modern<br />

world. The proliferation of nuclear weapons that are now in<br />

possession of at least four countries outside of the original<br />

five-power nuclear club, combined with concerns over the<br />

protection levels of non-military nuclear materials, seem<br />

to justify these concerns. This global problem merits the<br />

attention of the general membership of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the First Committee is the most appropriate venue to<br />

address it. The other topic, the militarization of the Arctic,<br />

is a long-unsolved regional issue that has global implications<br />

because of the direct involvement of some of the world’s<br />

mightiest powers – the <strong>United</strong> States, Russia, Canada,<br />

Norway, <strong>and</strong> Denmark. In view of the international status<br />

of the area, as well as the conflicting interests of the nations<br />

involved, it is crucial that the questions of territorial claims<br />

<strong>and</strong> military presence in the region be addressed by the<br />

General Assembly of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>.<br />

As delegates to the <strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong><br />

Committee, you have an opportunity to discuss these issues<br />

of supreme importance <strong>and</strong> to work collectively on designing<br />

viable solutions through the process of negotiation <strong>and</strong><br />

compromise.<br />

H I s t o r y of tHe commIt t e e<br />

The <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> was established at the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

Conference on <strong>International</strong> Organization in San<br />

Francisco, at which representatives of 50 independent states<br />

congregated to discuss the creation of ‘a general international<br />

organization to maintain peace <strong>and</strong> security.’ The Charter of<br />

the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> was written <strong>and</strong> ratified there, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Organization was officially formed on 24 October 1945.<br />

The <strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee,<br />

also known as the First Committee of the General Assembly of<br />

the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>, is a consensus-building body that gathers<br />

representatives of all 192 member states to collectively discuss<br />

issues pertaining to world peace <strong>and</strong> to h<strong>and</strong>le all questions<br />

relating to security <strong>and</strong> international law. Initially established<br />

as the Political <strong>and</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee (POLISEC), the First<br />

Committee was reorganized in the late 1970s in response<br />

to a growing number of additional political matters, <strong>and</strong><br />

the Special Political Committee was created. In view of the<br />

progress of decolonization movements <strong>and</strong> the declining<br />

number of issues to be addressed such as trust territories,<br />

the functions of the Special Political Committee were later<br />

merged during the 1990s into the Fourth Committee, which<br />

initially dealt with Trusteeship <strong>and</strong> Decolonization matters.<br />

The <strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee,<br />

just as any other of the six committees of the General<br />

Assembly, allows every nation represented to suggest or<br />

consider proposals relevant to the substantive topics covered,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to recommend resolutions for adoption by the General<br />

Representatives from all Member States convene at a<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee<br />

meeting to debate key security issues. http://graphics8.<br />

nytimes.com/images/2006/09/18/world/18un.l.jpg<br />

Assembly. While these resolutions are not legally binding, the<br />

fact that each of them represents an agreement of the majority<br />

of the member states implies that resolutions adopted by the<br />

General Assembly have a significant normative role. This<br />

means that they can indicate the establishment of common<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards, customs <strong>and</strong> guidelines for the behavior of<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 2

states on the international scene. 1 Resolutions adopted by<br />

consensus have an additional role of featuring substantive<br />

areas of agreement concerning world peace <strong>and</strong> can lay<br />

foundations for the creation of international treaties <strong>and</strong> the<br />

emergence of international legal norms. 2<br />

Article 11 of the Charter of the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> authorizes<br />

the General Assembly to discuss any questions relating to the<br />

maintenance of international peace <strong>and</strong> security <strong>and</strong> to make<br />

recommendations with regard to any such questions to the<br />

state or states concerned, to the <strong>Security</strong> Council, or to both. 3<br />

The First Committee provides a platform for member states<br />

to present their positions on disarmament-related matters,<br />

<strong>and</strong> provides an opportunity for nations to reach common<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>and</strong><br />

to agree on universal<br />

norms of behavior.<br />

Instead of ensuring<br />

security through the<br />

size of their arsenals,<br />

all states can discuss<br />

ways of arriving at<br />

collective security<br />

arrangements<br />

through the process<br />

of multilateral<br />

disarmament.<br />

The First Committee<br />

convenes every year<br />

in October for a<br />

4-5 week session,<br />

following a general<br />

debate of the<br />

General Assembly.<br />

At the beginning<br />

of each session, the<br />

Committee elects a Chairman, three Vice Chairmen <strong>and</strong> a<br />

Rapporteur to conduct the workings of the body.<br />

The most significant past successes of the <strong>Disarmament</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> Committee include the passage<br />

of the following treaties <strong>and</strong> acts: the Treaty on the Non-<br />

Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the Biological Weapons<br />

Convention, the Chemical Weapons Convention <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Partial Test Ban Treaty, among others.<br />

t o p I c A r e A A: m I l I tA r I z At I o n o f t H e<br />

A r c t I c<br />

History <strong>and</strong> Discussion of the Problem<br />

Geographical Features of the Region<br />

The Arctic is a region around the North Pole of the Earth,<br />

which includes the Arctic Ocean <strong>and</strong> parts of Canada,<br />

Russia, the <strong>United</strong> States, Greenl<strong>and</strong>, as a territory of<br />

Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong>. There exist<br />

different concepts about the region’s borders. It can be defined<br />

as the area north of the Arctic Circle (66° 30’N), which is the<br />

approximate limit of the midnight sun <strong>and</strong> the polar night.<br />

The polar night<br />

refers to the<br />

periods when<br />

the sun does<br />

not set or it does<br />

not rise. 4 This<br />

borderline has<br />

no geographical<br />

meaning, since<br />

it does not<br />

correspond to<br />

any features<br />

of the terrain.<br />

Alternatively,<br />

the Arctic can<br />

be defined as the<br />

northernmost<br />

limit of the<br />

The Arctic Map. http://invisibleman.com/arctic-map.gif<br />

st<strong>and</strong> of trees,<br />

which is roughly<br />

followed by the<br />

isotherm at the<br />

boundary of the<br />

region where<br />

the average temperature for the warmest month does not<br />

exceed 10°C.<br />

Brief History of Arctic Exploration<br />

By the time the first European explorers, the Norsemen<br />

or Vikings, visited the Arctic area, many parts of the<br />

region had already been settled by the Eskimos <strong>and</strong> other<br />

people of Mongolic stock. 5 The quest to further explore the<br />

vast <strong>and</strong> mysterious l<strong>and</strong>s above the 50th parallel in North<br />

America <strong>and</strong> above the 70th parallel in Eurasia began in the<br />

16th century <strong>and</strong> led to numerous expeditions over the scope<br />

of the next four centuries. Probably the most illustrious goal<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 3

Peary’s boys claiming finders-keepers on the North Pole. http://freedy89.<br />

files.wordpress.com/2009/02/peary5.jpg<br />

in the early history of Arctic exploration was the discovery<br />

of the Northern Passage – the legendary connection between<br />

the Pacific <strong>and</strong> the Atlantic, around North America or<br />

Eurasia – which would constitute a possible attractive trade<br />

route.<br />

The initial driving force for finding an alternate trade route to<br />

the Orient was the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in<br />

1453, which allowed them to control the Strait of Bosphorus<br />

<strong>and</strong> to interrupt trade between Europe <strong>and</strong> the Orient. 6 The<br />

first known expeditions for a new trade route to the Orient<br />

began with Columbus in 1492, followed by John Cabot,<br />

who, in 1497, l<strong>and</strong>ed much farther north than Columbus,<br />

probably in Newfoundl<strong>and</strong>, Giovanni da Verrazzano, who<br />

looked for a northwest passage around the recently explored<br />

l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>, in 1524, sailed as far north as Maine or Nova Scotia,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Jacques Cartier, who discovered the<br />

St. Lawrence River in 1535. 7 The journey<br />

further north <strong>and</strong> the passage through<br />

the Arctic Isl<strong>and</strong>s of Canada proved to be<br />

more dem<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> the early explorers<br />

had to contend with ice, Arctic weather,<br />

<strong>and</strong> scurvy, among other obstacles. The<br />

results of these early expeditions by<br />

European explorers <strong>and</strong> the subsequent<br />

ones – among them those by William<br />

Barentz, Martin Frobisher, William<br />

Baffin, Henry Hudson, <strong>and</strong> John Davis<br />

– were largely disappointing <strong>and</strong> caused<br />

the initial wave of interest to wane. 8 These<br />

expeditions played a great role, however, in<br />

adding to the Western Civilization’s initial<br />

knowledge of the Arctic.<br />

In the 19 th century, several new explorers<br />

took up the challenge of the Arctic –<br />

primarily British naval officers John<br />

Franklin, F. W. Beechey, John Ross, James<br />

Ross, W. E. Parry, P. W. Dease, Thomas<br />

Simpson, George Back, <strong>and</strong> John Rae. 9 In<br />

1845, one of the most famous expeditions<br />

ever to attempt the Northwest Passage, by<br />

Sir John Franklin, disappeared <strong>and</strong> gave<br />

rise to more than 40 searching parties<br />

that scoured the Arctic Isl<strong>and</strong>s for several<br />

decades vainly looking for Franklin <strong>and</strong><br />

his crew. 10 This drawback cooled Great<br />

Britain’s ambition to be the leader in the<br />

race for the Northern Passage <strong>and</strong> made<br />

most explorers shift their focus to the<br />

North Pole. These expeditions moved<br />

the ‘discovery line’ further north <strong>and</strong> explored <strong>and</strong> mapped<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>, together with some smaller Arctic isl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

The Northwest Passage between the Bering Strait, which<br />

separates Russia <strong>and</strong> Alaska, <strong>and</strong> Baffin Bay on the Atlantic<br />

Ocean was eventually conquered by Roald Amundsen in<br />

1903-1906, 25 years after the Northeast Passage had been first<br />

navigated by Nils A. E. Nordenskjöld. 11 In 1909, the race to the<br />

North Pole was arguably won by Robert E. Peary; however, his<br />

achievement was undermined by Frederic A. Cook’s subsequent<br />

announcement that he had reached the Pole a year before.<br />

There is still a considerable controversy as to whether either<br />

man actually reached the Pole, given the primitive navigation<br />

techniques of that period. In subsequent years, several field<br />

expeditions were sent out by British, Soviet, Norwegian, Danish,<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 4

Canadian <strong>and</strong> American organizations, but their objectives<br />

focused mainly on gathering meteorological, hydrological<br />

<strong>and</strong> magnetic data <strong>and</strong> establishing environmental <strong>and</strong> radio<br />

stations.<br />

During <strong>World</strong> War II, interest in studying the Arctic conditions<br />

was further fuelled by the need to transport supplies, <strong>and</strong> this<br />

interest continued also after the war had ended. Scientific<br />

work in the Arctic region increased greatly after 1945, with the<br />

intensified use of new methods of exploration. After 1947, the<br />

<strong>United</strong> States started carrying out routine weather-reporting<br />

flights over the Arctic Ocean <strong>and</strong> used icebreakers to conduct<br />

oceanographic work in the Beaufort Sea. The first American <strong>and</strong><br />

Soviet weather stations were established in the 1950s, <strong>and</strong> by<br />

the end of the decade there were several stations on ice isl<strong>and</strong>s,<br />

which were occupied <strong>and</strong> maintained until they drifted into a<br />

region where they ceased to be of interest to the scientists. 12 In<br />

regards to the Northwest Passage, in 1954 the first crossing by a<br />

deep-draught vessel was made by HMCS Labrador, a Canadian<br />

naval icebreaker, <strong>and</strong> in 1969 the Manhattan, one of the world’s<br />

largest commercial ships of that time, smashed through more<br />

than 1,000 km of ice between Baffin Bay <strong>and</strong> Point Barrow to<br />

assess the commercial feasibility of the passage. 13 Up to this<br />

day, however, the Northwest Passage has never been used as a<br />

regular commercial route.<br />

Presently, the discovery phase of the exploration of the<br />

Arctic region is over. Today, there remain no unexplored<br />

areas, as scientific research yielded reasonably accurate maps<br />

<strong>and</strong> technological progress has made this once elusive area<br />

increasingly accessible. Nowadays, commercial airlines can<br />

fly across the North Pole, <strong>and</strong> the Arctic regions have become<br />

the focus of research concerning global warming <strong>and</strong> climate<br />

change.<br />

Early Territorial Claims<br />

As a result of scientific exploration of the Arctic, it became<br />

increasingly attractive for many nations to claim their<br />

rights to territorial sovereignty over some portions of the<br />

region. From the very beginning, exploration of the Arctic<br />

often combined scientific, geopolitical, <strong>and</strong> even commercial<br />

purposes with the pursuit of national prestige. Therefore,<br />

arctic exploration was undertaken not only by the states<br />

bordering on the Arctic Ocean: the <strong>United</strong> States, the Soviet<br />

Union/Russia, Canada, Denmark-Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Norway,<br />

but also by actors such as Germany, the <strong>United</strong> Kingdom<br />

<strong>and</strong> Pol<strong>and</strong>. 14 However, territorial claims were mainly made<br />

by the former group of states – mainly the <strong>United</strong> States,<br />

the Soviet Union/Russia <strong>and</strong> Canada. As late as in the first<br />

decades of the 20th century, there was no international<br />

statute in place that would clearly regulate boundaries for<br />

all states in the Arctic region, but there seemed to be no<br />

urgent necessity to create one at that time. All countries of<br />

the Arctic rim traditionally accepted the sector principle,<br />

a version of the doctrine of contiguity, <strong>and</strong> facilely based<br />

their territorial claims on this agreement. According to the<br />

sector principle, the northern coastlines of the countries<br />

adjacent to the Arctic Circle were to indicate the northern<br />

boundaries of their respective sectors in the Arctic Ocean,<br />

while longitudinal parallels extending from their eastern<br />

<strong>and</strong> western borders bounded these sectors from the other<br />

two sides 15 .<br />

In the past, international law stated that national claims of<br />

sovereignty over particular areas in the Arctic Ocean were to<br />

be recognized only if accompanied by physical occupation.<br />

Initially, there were two competing theories regarding<br />

national sovereignty in the Arctic: (1) that no nation could<br />

achieve sovereignty over the Arctic, termed ‘res nullius’ <strong>and</strong><br />

(2) that every nation shared an undivided sovereignty over<br />

this region, called ‘res communes.’ According to current<br />

international law, sovereignty is considered to be a derivative<br />

of government control <strong>and</strong> of notoriety over new territory.<br />

Consequently, many claims of sovereignty over some portions<br />

of the Arctic region that were supported by existing exercise<br />

of the government functions became more plausible. On the<br />

other h<strong>and</strong>, claims resting solely on territorial justifications<br />

such as the sector principle were denied legal force by many<br />

nations, including the <strong>United</strong> States, which purchased Alaska<br />

from Russia in 1867, thus reaffirming its presence in the<br />

region.<br />

Extended sea sovereignty conflicts <strong>and</strong> disputes in the Arctic<br />

between the <strong>United</strong> States, Canada, the Soviet Union/Russia,<br />

Denmark-Greenl<strong>and</strong>, Norway, <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong> started in the<br />

1920s. The beginning of the wave of claims was marked by<br />

Norway’s acquisition of the Svalbard Archipelago, which was<br />

recognized by the Spitsbergen Treaty <strong>and</strong> which gave this<br />

country a large Arctic area. The littoral states of Canada <strong>and</strong><br />

the Soviet Union argued that their coastal reach should be<br />

extended northwards, repeating the argument that was made<br />

by claimants to the newly explored Antarctica. Canada’s claim<br />

involved extending their national boundaries up to the Pole,<br />

which would then cover the area between longitudes 60°W<br />

<strong>and</strong> 141°W <strong>and</strong> include the isl<strong>and</strong>s between the northern coast<br />

of Canada <strong>and</strong> the Pole. Russia followed suit, <strong>and</strong> established<br />

a claim to the area between the northern coasts of both its<br />

European <strong>and</strong> Asiatic parts <strong>and</strong> the North Pole. The Russian<br />

sector was to be bounded by two lines: from Murmansk to the<br />

North Pole (35°E) <strong>and</strong> from Chukchi Peninsula to the North<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 5

Svalbard serves as Norway’s Arctic refuge. http://www.etravelphotos.com/photos/2005sv/2005sv-0731-012d-w.jpg<br />

Pole (170°W). In the same manner, Norway decided to claim<br />

its sovereign rights to the sector between longitudes 5°E <strong>and</strong><br />

35°E, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>United</strong> States did the same, claiming the sector<br />

between 141°W <strong>and</strong> 170°W. Following this logic, Denmark<br />

could also claim its sovereignty over the sector between 60°W<br />

<strong>and</strong> 10°W, but it contented itself with Greenl<strong>and</strong>, which was<br />

internationally recognized as Danish territory in 1933.<br />

A new addition to the dispute over Arctic territory after<br />

<strong>World</strong> War II was the strategic military component, which<br />

emerged due to the new security situation when East-West<br />

tensions cemented. During the Cold War, all states bordering<br />

on the Arctic Ocean - the <strong>United</strong> States, the Soviet Union,<br />

Canada, Norway, Icel<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Denmark-Greenl<strong>and</strong> - divided<br />

themselves into the East-West confrontation framework. 16<br />

The Arctic’s strategic significance in this new era dramatically<br />

increased, as the region marked the shortest distance between<br />

the <strong>United</strong> States <strong>and</strong> the Soviet Union. Additional factors were<br />

also crucial in reviving the dispute over national sovereignty<br />

in the Arctic. From the Soviet Union’s perspective, the littoral<br />

coast of the Arctic Ocean played a key role in their naval<br />

build-up, in view of the fact that the Soviet Union had no<br />

warm-water ports with direct access to the world’s oceans. 17<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong>, the <strong>United</strong> States had no direct way to<br />

respond to this naval threat – they had no access to the Arctic<br />

waters save for Alaska <strong>and</strong> had to rely on agreements with<br />

other states like Canada, Denmark, <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong> to build up<br />

their defenses.<br />

As the <strong>United</strong> States security policy became increasingly<br />

dependent upon the relatively free access to the Canadian<br />

Arctic, disputes arose over whether Canadian cooperation<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 6

which regulated the practical<br />

issues without addressing<br />

the sovereignty dispute.<br />

According to the agreement,<br />

no vessels that were engaged<br />

in research, including US<br />

Coast Guard vessels, could<br />

enter the Canadian Arctic<br />

waters without permission of<br />

the Canadian government. 22<br />

was strictly or legally necessary. 18 The <strong>United</strong> States rejected<br />

the Canadian jurisdiction over the Northwest Passage –<br />

while it still recognized Canada’s rights to sovereignty over<br />

the isl<strong>and</strong>s of the Arctic Archipelago, it considered the Arctic<br />

Ocean as international waters. The <strong>United</strong> States claimed that<br />

the Northwest Passage in its entirety should be regarded as an<br />

international strait where foreign vessels have the unrestricted<br />

right of transit passage. Canada, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, claimed<br />

the Northwest Passage <strong>and</strong> the waters of the Canadian Arctic<br />

Archipelago as internal waters based on a liberal application<br />

of the doctrine of straight baselines. 19<br />

This long-running dispute featured intermittent testing<br />

behavior. In 1969, the world’s largest commercial vessel –<br />

the American tanker Manhattan – traveled through the<br />

Northwest Passage to test whether Alaskan oil could be<br />

delivered to the east coast of the <strong>United</strong> States by this route. 20<br />

The trip itself was not a problem for the Canadians, but the<br />

fact that the voyage took place without asking for permission<br />

of the Canadian government spurred indignation in this<br />

northern country. A similar journey was made by the <strong>United</strong><br />

States icebreaker Polar Sea in 1985, again without previous<br />

consultation with the authorities in Ottawa. 21 The Convention of the Law<br />

of the Sea<br />

The issue of competing<br />

claims for sovereignty<br />

over territorial waters was<br />

raised in the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

in 1967 by Malta, <strong>and</strong> this<br />

led to convening the Third<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Conference<br />

on the Law of the Sea in<br />

1973. In order to reduce<br />

the influence of organized<br />

groups of states influencing<br />

the negotiations, the st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

majority vote was replaced<br />

with a consensus process. This prolonged the negotiations,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the final agreement was reached only in 1982. The final<br />

treaty, the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Convention on the Law of the Sea<br />

(UNCLOS), was ratified in 1994 <strong>and</strong> became the single most<br />

significant international agreement regulating the rights <strong>and</strong><br />

responsibilities of nations in their use of the world’s high seas.<br />

Probably the single most important provision of the UNCLOS<br />

permitted coastal states to establish exclusive economic zones<br />

extending up to 200 nautical miles within which they could<br />

exercise sovereign rights over both the waters <strong>and</strong> the seabed.<br />

Furthermore, the treaty assured that this sovereign territory<br />

could be extended depending on how far the continental l<strong>and</strong><br />

mass belonging to a nation extended out under the ocean.<br />

As a result of<br />

these incidents, in 1988, the governments of Canada <strong>and</strong> of<br />

the <strong>United</strong> States signed an agreement, ‘Arctic Cooperation’,<br />

23 S.S. Manhattan’s epic journey through the Northwest Passage rendered Canada<br />

indignant. http://drake.marin.k12.ca.us/academics/rock/NWP_then_files/405_<br />

Manhattan.jpg<br />

To<br />

date, the Convention on the Law of the Sea has been ratified by<br />

158 countries, the <strong>United</strong> States being a noteworthy exception.<br />

Active Militarization<br />

Prior to <strong>World</strong> War II, the Arctic region was a complete<br />

military vacuum. During the War, its strategic role<br />

included mainly being a transit area for the Arctic convoys<br />

delivering vital supplies to the Arkhangelsk Soviet Union<br />

from the <strong>United</strong> Kingdom <strong>and</strong> the <strong>United</strong> States under the<br />

Lend-Lease Act. The region was also the area of a few smaller<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 7

engagements, like the Battle of the Barents Sea <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Battle of the North Cape. It was the post-war period, with its<br />

technological advances in the military sphere, however, that<br />

marked a boost in strategic importance of the Arctic. Defined<br />

solely in terms of its significance in scientific research, the<br />

Arctic started being<br />

regarded as the<br />

Circumpolar<br />

North – a potential<br />

core of national<br />

security interests of<br />

several countries. 24<br />

The Arctic region<br />

became an area<br />

for ballistic missile<br />

threats, early<br />

warning systems,<br />

<strong>and</strong> even potential<br />

naval conflicts. 25<br />

This development<br />

can be explained<br />

on the basis of the<br />

interplay of the<br />

following three<br />

factors: (1) the<br />

East-West conflict,<br />

which created<br />

the political<br />

framework for<br />

bloc formation; (2)<br />

the developments<br />

in military<br />

technology,<br />

including nuclear<br />

weapons <strong>and</strong> longrange<br />

means of<br />

delivery; <strong>and</strong> (3)<br />

the geo-strategic<br />

factors particular to<br />

the Arctic region. 26<br />

While the first<br />

two factors created a need for deployment areas in general,<br />

the universal features of the Arctic explain the particular<br />

significance of this region. These geo-strategic properties of the<br />

Circumpolar North are commonly known. First, the shortest<br />

distance between Europe, Asia <strong>and</strong> North America, <strong>and</strong> thus<br />

between the two superpowers of the Cold War period, the<br />

<strong>United</strong> States <strong>and</strong> the Soviet Union, is over the Arctic Ocean.<br />

The superpowers can be also said to have an almost common<br />

border in this area, where the Soviet Union is separated from<br />

Alaska by only 91 km of the Bering Strait. 27 Furthermore,<br />

eighty percent of the world’s industrial production takes place<br />

north of 30°N, while seventy percent of the world’s major<br />

cities are located north of 23.5°N. 28 These factors explain why<br />

the Arctic started being regarded as a natural route for any<br />

nuclear attack using<br />

or intercontinental<br />

missiles or strategic<br />

bombers <strong>and</strong> the rise<br />

of the Cold War.<br />

In addition to this,<br />

the Soviet Union<br />

gradually developed<br />

its Northern Fleet,<br />

based at the Kola<br />

Peninsula, to become<br />

its most powerful<br />

fleet. The reasons<br />

for this were purely<br />

pragmatic – the<br />

Soviet Union aspired<br />

to be a naval power,<br />

but being a partly<br />

l<strong>and</strong>locked country,<br />

it faced obvious<br />

geographical<br />

restrictions in its<br />

access to the world’s<br />

high seas. All of its<br />

fleets – the Black<br />

Sea, the Baltic, the<br />

Northern, <strong>and</strong> –<br />

partly – the Pacific<br />

Fleet were dependent<br />

on passing through<br />

straits that were<br />

controlled by powers<br />

with a history of<br />

imperfect relations<br />

with the Soviet<br />

Union. 29 The Soviets thus faced a constant risk of seeing these<br />

straits closed for passage at the most crucial moments. The<br />

Northern Fleet was an exception in this regard, having a direct<br />

access to the world’s oceans <strong>and</strong> thus played a crucial role in<br />

assuring the Soviet Union’s naval strength. The introduction<br />

of the Delta-class submarines in 1972 further increased the<br />

potential of the Northern Fleet, which did not have to rely on<br />

the barrier-protected GIUK gap, which is between Greenl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Russia has crucial naval facilities in the Barents Sea. http://www.astrosol.<br />

ch/images/northernfleetmap.jpg<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 8

Icel<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the <strong>United</strong> Kingdom, anymore – since Delta<br />

submarines were capable of striking any target in Europe or<br />

North America from the Arctic waters. 30 This withdrawal of the<br />

Northern Fleet’s strategic forces to the Arctic Ocean has led the<br />

<strong>United</strong> States to follow suit <strong>and</strong> transformed this region into a<br />

military front. 31 Also the airspace over the Arctic Ocean began<br />

to be utilized for strategic deterrence in the 1950s <strong>and</strong> 1960s.<br />

Due to the long-range missile threat, the <strong>United</strong> States set up<br />

several chains of early warning systems against attacks from<br />

the Circumpolar North. The Distant Early Warning (DEW)<br />

stations were established between Alaska <strong>and</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>, in<br />

cooperation with Canada <strong>and</strong> Denmark. In addition to these,<br />

three additional chains of radars were built in North America:<br />

the Mid Canada line, the Pinetree line, <strong>and</strong> the Ballistic<br />

Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS). 32 Other countries<br />

also assured their safety in case of war. Sweden, even though<br />

it decided to remain neutral, also maintained substantial<br />

forces in its northern areas to ensure that no country would be<br />

tempted to utilize its territory to conduct an assault. Norway<br />

also made appropriate provisions to ensure it could respond<br />

to a Soviet attack.<br />

The climax of the process of militarization <strong>and</strong> of the role of<br />

the Arctic as a theatre for the operations of strategic weapons<br />

systems came in the 1980s. As l<strong>and</strong>-based intercontinental<br />

ballistic missiles (ICBMs) became increasingly vulnerable to<br />

counterforce strikes, submarine-launched ballistic missiles<br />

(SLBMs) began to play a pivotal role in military strategy of<br />

both the <strong>United</strong> States <strong>and</strong> the Soviet Union. At the same<br />

time, development of ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs)<br />

allowed military strategists to achieve huge advantages by<br />

deploying them in the Arctic. First, SSBNs in patrol stations<br />

in the Arctic Ocean could strike virtually all enemy targets<br />

without venturing far from their respective homel<strong>and</strong>s –<br />

for example, Soviet-built missiles mounted on Delta-class<br />

submarines stationed in Arctic waters could attack targets<br />

in North America <strong>and</strong> Europe. Similarly, American Trident<br />

submarines carrying C-4 missiles were able to deliver nuclear<br />

warheads to targets throughout the Soviet Union – all from<br />

the Arctic waters. Simultaneously, the operation of SSBNs in<br />

the Arctic Ocean was remarkably safe due to the difficulties<br />

of locating submarines in Arctic conditions. The effectiveness<br />

of acoustical monitoring devices like sonar systems was<br />

significantly compromised by the ambient noise of the pack<br />

of ice. 33<br />

These military advantages were eagerly exploited by both<br />

the Soviets <strong>and</strong> the Americans during the 1980s: over half<br />

of the Soviet SSBNs were stationed with the Northern Fleet<br />

in the Kola Peninsula, with an easy access to Arctic waters.<br />

Although the <strong>United</strong> States did not have a comparable base,<br />

their SSBNs that were stationed in Bangor, Washington were<br />

fully operational in Arctic waters even for extended periods<br />

of time. The <strong>United</strong> States accelerated the construction of its<br />

fleet of Ohio-class submarines, equipped with Trident II or<br />

D-5 missiles. In fact, the safety <strong>and</strong> ease of operation offered<br />

by Arctic waters convinced the American military strategists<br />

to deploy vessels extensively in this region, even though the<br />

<strong>United</strong> States did not share the Soviet Union’s problems such<br />

as penetrating the GIUK gap. 34<br />

The situation was largely similar with air-launched cruise<br />

missiles (ALCMs), which were developed so that they could<br />

deliver nuclear warheads with great precision. Their advantage<br />

over ballistic missiles results from their maneuverability –<br />

unlike SSBMs, ALCMs are subject to control at all points<br />

along their flight paths – <strong>and</strong> their ability to confuse ordinary<br />

radar scanners. By flying at low speeds <strong>and</strong> altitudes, they were<br />

often capable of avoiding conventional air defense systems.<br />

In the 1980s, long-range cruise missiles could travel up to<br />

3,000 km to their target areas <strong>and</strong>, when mounted on heavy<br />

bombers, were fully operational in the Arctic airspace. The<br />

<strong>United</strong> States had over a thous<strong>and</strong> long-range cruise missiles<br />

in their inventory <strong>and</strong> several squadrons of B-52G bombers<br />

to carry them. The Soviet Union lagged somewhat behind<br />

in this technology, but the Soviets were also in possession<br />

of long-range ALCMs that they mounted on their Backfire<br />

<strong>and</strong> Bear H bombers. The deployment of long-range ALCMs<br />

<strong>and</strong> the latest generations of manned bombers significantly<br />

increased the importance of the Arctic airspace as a potential<br />

battlefield. These missiles were capable of reaching most<br />

targets in North America, Europe <strong>and</strong> the Soviet Union when<br />

launched from the airspace over the Arctic region, which<br />

potentially made st<strong>and</strong>off nuclear strikes relatively safe <strong>and</strong><br />

effective. 35<br />

As a result of these developments of offensive military<br />

systems in the Arctic, there emerged a much stronger need<br />

for sea <strong>and</strong> air defense systems in the region. In regards<br />

to sea defense, conventional methods of monitoring the<br />

movements of submarines from aircraft, satellites or other<br />

acoustical devices were rather useless in tracking the activities<br />

of SSBNs operating under the ice of the Arctic Ocean. The<br />

only measure of defense was deploying attack submarines<br />

in the Arctic, which increased the military presence in the<br />

region even further. A similar surge of interest in air defense<br />

systems, caused by the deployment of ALCMs, precipitated a<br />

modernization of the DEW line from the 1950s in the <strong>United</strong><br />

States. This resulted in creation of the North Warning System<br />

in cooperation with Canada, which was based on a military<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 9

agreement from 1985. The North Warning System contained<br />

13 medium-range microwave radars <strong>and</strong> 39 short-range<br />

radars. In a separate agreement, the <strong>United</strong> States <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong><br />

agreed to construct two additional radar stations in Icel<strong>and</strong> to<br />

monitor Soviet activities in the Arctic. 36<br />

After the end of the Cold War, most Arctic nations reduced<br />

the accumulation of forces in their northern areas. The<br />

explanation for this change can be attributed to a combination<br />

of economic challenges faced by the newly transformed<br />

Russian Federation, <strong>and</strong> the growing need for US military<br />

resources to be deployed elsewhere. This led to the decreasing<br />

necessity for major Arctic powers to maintain their large<br />

military presence in the Arctic region.<br />

Current Situation<br />

The Arctic is presently re-emerging as a strategic area where<br />

vital interests of many countries coincide. The region’s<br />

geopolitical <strong>and</strong> geo-economic significance, combined with<br />

its wealth in natural resources, is transforming the Arctic<br />

into a hotly contested frontier of the 21st century.<br />

Natural Resources<br />

The <strong>United</strong> States<br />

Geological<br />

Survey estimates<br />

that the Arctic may<br />

contain a fifth of the<br />

world’s yet-to-bediscovered<br />

oil <strong>and</strong><br />

natural gas reserves.<br />

The assessment,<br />

which took four<br />

years, found that<br />

the region may<br />

hold as much as<br />

90 billion barrels<br />

of undiscovered<br />

oil reserves, which<br />

constitutes 13% of<br />

the estimated total<br />

world reserves,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 47.3 trillion<br />

cubic meters of<br />

undiscovered natural<br />

gas reserves, which<br />

is 30% of the world’s<br />

reserves. 37 At today’s<br />

consumption rate of<br />

86 million barrels per<br />

day, the potential oil to be drilled in the Arctic could meet<br />

global dem<strong>and</strong> for almost three years. 38 The Arctic’s potential<br />

natural gas resources are three times bigger <strong>and</strong> equal to<br />

Russia’s proven gas reserves, which are the world’s largest. The<br />

survey looked at resources believed to be recoverable using<br />

existing technology, but with the important assumptions for<br />

offshore areas that the resources would be recoverable even in<br />

the presence of permanent sea ice <strong>and</strong> oceanic water depth. 39<br />

Two regions of the Arctic st<strong>and</strong> out according to this survey.<br />

A third of the yet-to-be-discovered Arctic oil, or about 30<br />

billion barrels, is off the coast of Alaska. 40 Historically,<br />

the North Slope, which is the region of Alaska from the<br />

Canadian border on the east to the Chukchi Sea Outer<br />

Continental Shelf on the west has contributed significantly to<br />

US oil production. The <strong>United</strong> States Department of Energy<br />

reported that the North Slope potentially holds 36 billion<br />

barrels of oil <strong>and</strong> 3.8 trillion cubic meters of natural gas, close<br />

to Nigeria’s proven reserves. 41 These reserves are also quite<br />

unique <strong>and</strong> attractive because their development is much less<br />

limited by government legislation. Therefore, they are much<br />

more accessible to drilling than other similar oilfields. Last<br />

year, oil companies spent US$2.6 billion to acquire leases on<br />

Oil exploration <strong>and</strong> drilling damage the Arctic blossoms. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/<br />

news/bigphotos/images/070824-arctic-oil_big.jpg<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 10 10

government-controlled offshore tracts. 42 Currently, however,<br />

many oil fields in the North Slope are in decline <strong>and</strong> many<br />

people in America look toward the offshore areas to revive<br />

the Alaskan oil industry <strong>and</strong> enhance US energy security.<br />

For example, the 10-billion-barrel oil reserves in the Arctic<br />

National Wildlife Refuge could lead to an additional 1 million<br />

barrels per day in American production capacity, which<br />

would save the <strong>United</strong> States US$123 billion in petroleum<br />

imports <strong>and</strong> create US$7.7 billion in new economic activity 43 .<br />

The other area of the Arctic that is particularly rich in<br />

natural resources is the ‘Russian area of water proper,’<br />

composed of the Barents Sea, the Pechora Sea, the Kara Sea,<br />

the East Siberian Sea, the Chukchi Sea, <strong>and</strong> the Laptev Sea.<br />

According to a report by the Russian Ministry for Natural<br />

Resources, oil deposits there could reach 418 million tons,<br />

which is equivalent to 3 billion barrels, <strong>and</strong> proven natural<br />

gas reserves could amount to 7.7 trillion cubic meters.<br />

Unexplored reserves are far larger – this region could hold<br />

as much as 67.7 billion barrels of oil <strong>and</strong> 88.3 trillion cubic<br />

meters of gas. 44<br />

Beside oil <strong>and</strong> gas, the Arctic seabed could also hold other<br />

natural wealth, such as significant deposits of precious<br />

stones – gold, silver, copper, iron, platinum, lead, tin, nickel,<br />

manganese, zinc <strong>and</strong> even diamonds. In the current state<br />

of global economy, dem<strong>and</strong> for these commodities steadily<br />

increases. Furthermore, it has been proven that there are large<br />

deposits of methane hydrates located on the deep seabed<br />

of the Arctic Ocean. While no technology currently exists<br />

that would make extracting them possible, the emergence<br />

of this capability seems to be an imminent prospect. Several<br />

countries are interested in developing methane hydrate<br />

processing as a commercially viable energy source, including<br />

the <strong>United</strong> States, Japan, <strong>and</strong> South Korea. 45<br />

Climate Change<br />

Nowhere else on the planet have such dramatic<br />

consequences of climate change been observed as in<br />

the Arctic. Biologists <strong>and</strong> climate researchers observe with<br />

mounting fear how the sea ice<br />

in the Arctic Ocean is rapidly<br />

decreasing <strong>and</strong> the permafrost<br />

on the ground is melting.<br />

According to data gathered<br />

by satellites, it is apparent that<br />

there is less sea ice between<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Siberia than<br />

ever before. 46 In August 2006,<br />

the Russian ship Akademik<br />

Fyodorov successfully managed<br />

to cross the North Pole<br />

without needing assistance of<br />

icebreakers; there are hardly any<br />

ice floes left in the Northwest<br />

Passage. 47 Some researchers<br />

hypothesize that by the end of<br />

the century the Arctic Ocean<br />

could become completely free<br />

of all ice in the summer <strong>and</strong><br />

up to 90% of the hard-rock<br />

surface could melt, shifting the<br />

permafrost border hundreds of<br />

kilometers to the north. 48 The<br />

warming effect also threatens<br />

to bring massive changes to<br />

the region’s environmental<br />

condition, whose balance<br />

Arctic ice is melting faster than ever before. http://www.spiegel.de/international/ has already been shaken by<br />

spiegel/0,1518,409001,00.html<br />

pollution <strong>and</strong> higher levels of<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 11 11

ultraviolet rays.<br />

However, as scientists <strong>and</strong> conservationists worry about the<br />

potentially dire consequences of global warming, politicians<br />

<strong>and</strong> businessmen have already started battling over how to<br />

reap the economic benefits of the global meltdown. A broad<br />

range of potential opportunities is opening up as the ice is<br />

melting. Cargo may be able to travel from North America<br />

to Asia more quickly <strong>and</strong> cheaply, as the Northern Route<br />

just north of the coast of Siberia opens up. Similarly, the<br />

fabled Northern Passage becomes much more accessible <strong>and</strong><br />

becomes a feasible commercial route from the west to the east<br />

coast of the <strong>United</strong> States. Local governments <strong>and</strong> firms are<br />

A robotic arm of a Russian mini submarine planting a<br />

titanium capsutre with a Russian flag under the icecaps<br />

of the Arctice Ocean at the North Pole.<br />

http://wwwimage.cbsnews.com/images/2007/09/21/<br />

image3284091g.jpg<br />

also hoping for newly accessible fishing grounds, especially<br />

around the Bering Strait. 49 More than anything else, however,<br />

it is the wealth of newly available natural resources that sparks<br />

the imagination of many. If the environmental processes that<br />

are currently underway continue, excavating the Arctic’s vast<br />

oil <strong>and</strong> natural gas reserves will soon become financially<br />

viable. 50 Several Arctic nations have recently started lining<br />

up to claim their rights to explore the Arctic’s riches.<br />

Recent Territorial Claims<br />

Until the end of the 20th century, there was a general<br />

consensus among most countries that the North Pole<br />

<strong>and</strong> most of the Arctic Ocean should be regarded as an<br />

international territory. At the same time, several states have<br />

reinforced their pre-existing claims to national sovereignty<br />

over certain areas in the region in view of the recent<br />

phenomenon of global warming <strong>and</strong> the resulting Arctic<br />

shrinkage. These emerging opportunities have led others<br />

to even establish completely new claims. According to the<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Convention on the Law of the Sea, countries<br />

are entitled to exclusive economic zones up to 200 miles<br />

from their shores, but some nations have recently filed claims<br />

to extend their respective areas.<br />

In 2001, Russia submitted to the UNCLOS a formal claim<br />

for an area of 1.2 million square kilometers that extends<br />

from the undersea Lomonosov Ridge <strong>and</strong> Mendeleev Ridge<br />

to the North Pole. 51 The claim stated that the Lomonosov<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mendeleev submerged ridges were in fact extensions of<br />

Russia’s continental shelf. The <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> commission<br />

rejected the claim <strong>and</strong> asked for more evidence in support of<br />

the Russian sovereign rights to this area. In response, Moscow<br />

sent a scientific expedition in 2007 of a nuclear-powered<br />

icebreaker <strong>and</strong> two submarines to the region in question.<br />

The mission collected samples from the Lomonosov Ridge to<br />

prove that the ridge is part of the Eurasian l<strong>and</strong>mass. During<br />

a spectacular media event, the submarines also dropped a<br />

titanium capsule containing a Russian flag onto the seafloor<br />

at the North Pole at a depth of 4,261 meters. This symbolic<br />

act by the Russians suddenly transformed the question of<br />

sovereign rights in the Arctic region from a purely scientific<br />

<strong>and</strong> legal case into an urgent political issue. 52 On the basis<br />

of the samples found, Russia’s Ministry of Natural Resources<br />

said that a preliminary analysis ‘confirms the fact that the<br />

structure of the Lomonosov Ridge crust matches world<br />

analogs of continental crust’. The Russian government used<br />

this fact to announce that the North Pole is part of Mother<br />

Russia <strong>and</strong> that under international law, Russia can lay claim<br />

to the potentially oil-rich seabed under the Arctic ice. 53 Many<br />

experts challenge this view, however, saying that the samples<br />

only prove that the Lomonosov Ridge’s rocks are continental<br />

in nature, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that the ridge is<br />

part of Russia – it could as well be Canadian or Danish. 54<br />

Meanwhile, scientists from other Arctic nations are looking<br />

for evidence to support very different versions of the<br />

truth about the Lomonosov Ridge. Danish geologists are<br />

attempting to prove that the ridge is connected to Greenl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Canadian scientists are searching for connections<br />

between this geological formation <strong>and</strong> the Ellesmere Isl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

a Canadian territory. 55 The dispute over which country’s<br />

continental shelf extends to the Lomonosov Ridge is crucial<br />

in determining which country has sovereign rights over<br />

the seabed around the North Pole. Some of the other hotly<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 12 12

contested areas of the Arctic are the boundary between Alaska<br />

<strong>and</strong> Canada, <strong>and</strong> the East Barents Basins, where Russia <strong>and</strong><br />

Norway are involved in bilateral discussions concerning the<br />

offshore boundary. 56<br />

In 2006, Norway followed Russia <strong>and</strong> also made an official<br />

submission into the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Commission on the<br />

Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Convention on the Law of the Sea (Article<br />

76, Paragraph 8). The claim to extend the Norwegian 200<br />

nautical miles (370 km) zone in three areas of the Arctic – the<br />

Western Nansen Basin in the Arctic Ocean, the Loop Hole in<br />

the Barents Sea <strong>and</strong> the Banana Hole in the Norwegian Sea<br />

– was backed by the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> commission, <strong>and</strong> thus<br />

the extension was effective <strong>and</strong> the total gain for Norway<br />

amounted to 235,000 square kilometers. 57 In 2007, a US Coast<br />

Guard icebreaker USCGC Healy headed to the Arctic to map<br />

the bottom of the Arctic Ocean the Outer Continental Shelf.<br />

One of the purposes of mapping was to determine whether<br />

the <strong>United</strong> States had any legitimate claims to territory<br />

beyond its 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone. 58<br />

Recent Militarization<br />

In August 2007, shortly after sending the scientific<br />

expedition to the Lomonosov Ridge that placed the<br />

Russian flag on the seabed, Moscow ordered resumption of<br />

regular air patrols over the Arctic Ocean. Strategic bombers<br />

including the turboprop Tu-95 (Bear), supersonic Tu-160<br />

(Blackjack), <strong>and</strong> Tu-22M3, as well as the long-range antisubmarine<br />

warfare patrol aircraft Tu-142 have flown patrols<br />

since then. 59 According to the Russian Air Force, the Tu-<br />

95 bombers refueled in-flight to extend their operational<br />

patrol area. 60 American newspapers reported that Russian<br />

bombers penetrated the 12-mile air defense identification<br />

zone surrounding Alaska several times since 2007. 61 Also<br />

the Russian navy is intensifying its patrols in the Arctic –<br />

this is the first such phenomenon since the end of the Cold<br />

War. High ranking Russian army officers say that Russia’s<br />

military strategy might be reoriented to meet threats to<br />

the country’s interests in the Arctic <strong>and</strong> that the Northern<br />

Fleet’s operational radius is being extended. 62 In July 2008,<br />

the Russian Navy officially announced that it has resumed its<br />

warship presence in the Arctic.<br />

The intensified Russian military activity in the Arctic is<br />

interpreted as an attempt to increase its leverage vis-à-vis<br />

territorial claims in the region. Moscow’s strategy seems to be<br />

to display its military might while invoking international law.<br />

For example, the Russian Navy deployed an anti-submarine<br />

warfare destroyer <strong>and</strong> guided-missile cruiser designed<br />

Maritime zones as defined by international law. http://<br />

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zonmar-en.svg<br />

to destroy aircraft carriers in the area of the Spitsbergen<br />

Archipelago. The Spitsbergen unambiguously belongs to<br />

Norway, but Russia refuses to recognize Norway’s rights to a<br />

200-nautical-mile economic zone around the Archipelago. 63<br />

The sorties of the Northern Fleet in the area are being justified<br />

by the Russian Navy as ‘fulfilled strictly in accordance with<br />

the international maritime law, including the UNCLOS 64 . In<br />

a recent report released in May 2009, the Russian <strong>Security</strong><br />

Council, which includes the Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin,<br />

<strong>and</strong> heads of the military <strong>and</strong> intelligence agencies, raised a<br />

possibility of war in the Arctic within a decade over control<br />

of the regions huge wealth of natural resources. 65<br />

Harvard <strong>World</strong>MUN 2012<br />

<strong>Disarmament</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Security</strong> 13 13

In response, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)<br />

partners re-supply the Thule Air Base in Greenl<strong>and</strong>, which<br />

operates under agreements with Denmark. Another example<br />

of this increased military attention given to the Arctic region<br />

is the strategic cooperation between the <strong>United</strong> States <strong>and</strong><br />

Canada in strengthening the North American Aerospace<br />

Defense Comm<strong>and</strong> (NORAD). There are also plans in the<br />

<strong>United</strong> States to establish a Joint Task Force–Arctic Region<br />

Comm<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> an Arctic Coast Guard Forum modeled after<br />

the highly successful North Pacific Coast Guard Forum. 66<br />

Canada joined the trend by announcing in 2007 <strong>and</strong> that<br />

it would build six to eight navy patrol ships to guard the<br />

Northwest Passage, as well as two military bases <strong>and</strong> a deepwater<br />

port inside the Arctic Circle. 67 \<br />

Past UN Actions<br />

The <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> Convention on the Law of the Sea<br />

The questions of jurisdiction over the Arctic <strong>and</strong> the<br />

militarization of the region have not yet been the topics<br />

of any major international treaty. The single most important<br />

agreement regulating sovereign rights in the Arctic, as well<br />

as in the other sea areas of the world, is the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The agreement,<br />

which is often described as the ‘constitution for the oceans’,<br />

was concluded in 1982 after nine years of work by the <strong>United</strong><br />

<strong>Nations</strong> Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) <strong>and</strong><br />

came into force in 1994 after the 60th country ratified the<br />

treaty. To date, 158 countries have ratified the Convention,<br />

but the <strong>United</strong> States has not yet done so, although it helped<br />

shape the Convention <strong>and</strong> signed the 1994 Agreement on<br />

Implementation.<br />

The Convention is crucial in regulating navigation in<br />

the Arctic waters, particularly in the Northwest Passage.<br />

According to the Convention, each country can extend its<br />

sovereign territorial waters to a maximum of 12 nautical<br />

miles (22 km) beyond its coast, but foreign vessels are<br />

granted the right of innocent passage through this zone, as<br />

long as they do not engage in hostile activities against the<br />

coastal state. The Convention also endorses a new concept of<br />

‘transit passage,’ which is in fact a compromise that combines<br />

the legally accepted provisions of innocent passage through<br />

territorial waters <strong>and</strong> freedom of navigation on the high seas.<br />

The concept of transit passage retains the international status<br />