Press Corps - World Model United Nations

Press Corps - World Model United Nations

Press Corps - World Model United Nations

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

of selling an expensive physical good. The Huffington<br />

Post and the Philadelphia Inquirer play the same game,<br />

but by vastly different rules. 12 , 13 Still, though, the rules<br />

of print and the Web have much more in common<br />

with each other than they do with those of the public<br />

sphere’s twenty-first century darling, Twitter.<br />

twitter, one could argue, is the telegraph of<br />

today. used for transmission of short messages<br />

(though arbitrarily, rather than economically limited),<br />

the service offers its users (and onlookers) the<br />

opportunity to view in real time the updates other<br />

users provide—about anything. These range from the<br />

mundane to the truly groundbreaking. Its role as the<br />

social media tool of the Arab Spring helped reveal its<br />

international use. News frequently breaks on Twitter<br />

and then is further explicated on an agency’s own<br />

site. However, not only has the medium where news<br />

is broken changed—from print to television to the<br />

Web to Twitter—but so too have the people doing<br />

it. The Internet, and broadcast systems like Twitter<br />

especially, have birthed a new kind of reporter: the<br />

citizen-journalist.<br />

The nature of Twitter’s network as a one-tomany<br />

broadcast network, combined with its core<br />

gimmick, the 140-character limit, have propelled it<br />

to such a prominent place in today’s public sphere.<br />

While Twitter resembles most of history’s broadcast<br />

networks in that it allows one person to disseminate<br />

information to many without providing a clear<br />

interface for conversation, it differs from them in<br />

one essential way: like the Internet, Twitter invites<br />

anyone to participate. in two main ways, though, it<br />

is even better suited for the purpose of kindling the<br />

public discourse because: a) it represents a single<br />

destination where global trends are algorithmically<br />

tracked and b) it is even more accessible than the<br />

Web. Designed for a world before smartphones and<br />

utilized in the developing countries where those<br />

devices’ penetration remains minimal, that “core<br />

gimmick” had and still has a real purpose: enabling<br />

the global broadcast of messages small enough to<br />

fit in a single SMS. The prepaid phones of the Third<br />

<strong>World</strong>, where present, have allowed the rest of the<br />

planet to follow in real-time the political strife of, for<br />

instance, the Arab Spring.<br />

Twitter has proven the most prominent vehicle<br />

of the citizen-journalist’s rise, but others exist and<br />

continue to grow in importance. Among them,<br />

YouTube, and to a lesser extent, Facebook, rank high.<br />

The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in<br />

Journalism in July 2012 highlighted the ascendancy of<br />

YouTube on its journalistic merits. The rise of videocapable<br />

phones, coupled with YouTube’s massive<br />

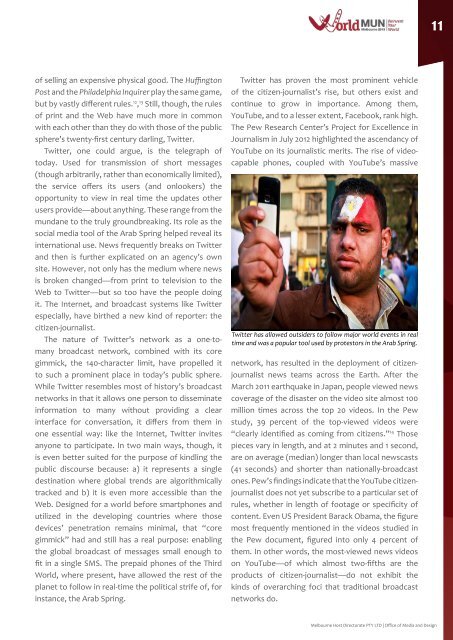

Twitter has allowed outsiders to follow major world events in real<br />

time and was a popular tool used by protestors in the Arab Spring.<br />

network, has resulted in the deployment of citizenjournalist<br />

news teams across the earth. After the<br />

March 2011 earthquake in Japan, people viewed news<br />

coverage of the disaster on the video site almost 100<br />

million times across the top 20 videos. In the Pew<br />

study, 39 percent of the top-viewed videos were<br />

“clearly identified as coming from citizens.” 14 those<br />

pieces vary in length, and at 2 minutes and 1 second,<br />

are on average (median) longer than local newscasts<br />

(41 seconds) and shorter than nationally-broadcast<br />

ones. Pew’s findings indicate that the YouTube citizenjournalist<br />

does not yet subscribe to a particular set of<br />

rules, whether in length of footage or specificity of<br />

content. Even US President Barack Obama, the figure<br />

most frequently mentioned in the videos studied in<br />

the Pew document, figured into only 4 percent of<br />

them. In other words, the most-viewed news videos<br />

on YouTube—of which almost two-fifths are the<br />

products of citizen-journalist—do not exhibit the<br />

kinds of overarching foci that traditional broadcast<br />

networks do.<br />

11<br />

Melbourne Host Directorate PTY LTD | Office of Media and Design