Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

50<br />

HISTORY<br />

Katowice can count itself<br />

as one of Poland’s newer<br />

cities, and a direct result of<br />

the industrial age. That’s not<br />

to say the region was a barren<br />

wasteland prior to the<br />

age of steam. The history<br />

books suggest the area was<br />

inhabited by ethnic Silesians<br />

centuries earlier, with the<br />

first recorded settlement<br />

being the village of Krasny<br />

Dab, whose existence was<br />

officially chronicled in 1299.<br />

<strong>In</strong> 1598 a village called Villa Nova was also documented to<br />

stand in the area now taken up by Katowice. By this time the<br />

region had changed from Bohemian hands to the domain of<br />

the Habsburg dynasty.<br />

Things started hotting up in 1742 when the area changed<br />

hands once more, this time as the property of the Prussians.<br />

1788 saw Karolina - the area’s first mine - opened,<br />

and by 1822 historic documents note 102 homesteads<br />

in the village of Katowice. Two years later the first school<br />

was opened and Katowice started making its first steps<br />

into adulthood. What really set the ball rolling was the<br />

construction of a railway station in 1847. <strong>In</strong>dustrialist and<br />

mining mogul Franz Winkler saw this as an opportunity to<br />

build up the mines he owned in the region, and Katowice<br />

was quickly developed as an industrial town. September<br />

11, 1865, saw Katowice awarded municipal rights and by<br />

1875 it had grown to hold over 11,000 residents, of which<br />

half were of Polish ethnicity. The city continued to prosper<br />

as an industrial heartland, with coal and steel industries<br />

flourishing. By 1897 it was officially designated as a city,<br />

though the streets were anything but a happy place; the<br />

even split in population between Germans and Poles was<br />

already causing friction.<br />

After the defeat of Germany in WWI, and the founding of a<br />

newly independent Polish state, native Poles - inspired by<br />

the rhetoric of Wojciech Korfanty - staged three uprisings<br />

between 1919 and 1921 in a bid to have the Silesia region<br />

incorporated into the Second Polish Republic. To prevent<br />

outright war from breaking out the League of Nations<br />

finally intervened and in 1922 divided the region beween<br />

both Poles and Germans. Kattowitz, as it was known<br />

before this date, fell on the Polish side of the divide and<br />

inexplicably became an autonomous voivodeship - a privelege<br />

unique from any other province in PL. The inter-war<br />

years marked a golden age for the city, with the building<br />

of the Silesian Parliament complex and one of Poland’s<br />

first skyscrapers (Cloud Scraper) being symbolic of the<br />

march into the future.<br />

Bad news was lurking around the corner though, and in spite<br />

of a heroic defence the city fell under German control on<br />

September 6, 1939. Aside from the savage destruction of the<br />

synagogue and the Silesian Museum, physically speaking the<br />

city escaped the fiery fate of many eastern cities, and found<br />

itself used as a major centre of manufacturing by the Nazis.<br />

Liberation came in the form of Soviet tanks in 1945, and the<br />

city was once more Polish - in theory. Between 1953 and<br />

1956 it was renamed Stalinograd, and a period of thoughtless<br />

development followed; the primitive exploitation of the region’s<br />

natural resources saw it marked out as an environmental<br />

blackspot with horrific pollution problems. Although there was<br />

plenty of work in the mines and steel mills, popular unrest with<br />

the communist system was growing fast. Living standards had<br />

plummeted, with empty shop shelves and round-the-block<br />

queues a common sight. <strong>In</strong> 1980 a series of strikes inspired by<br />

the Gdańsk born Solidarity movement quickly spread around<br />

the country. Demands for better living conditions were initially<br />

met, but Solidarity continued to lobby for further reforms and<br />

free elections. The Kremlin was furious, and with Soviet invasion<br />

a looming threat, appointed communist president Jaruzelski<br />

declared a state of martial law on December 13, 1981.<br />

Tanks roared into the street, subversives were arrested and<br />

telephone lines were cut. On December 16 a military assault<br />

was launched on striking miners in Katowice’s ‘Wujek’ mine,<br />

resulting in the deaths of nine workers. With Solidarity officially<br />

dissolved and its leaders imprisoned, discontent was growing.<br />

John Paul II visited Poland, and Katowice, once more in 1983,<br />

his mere presence igniting hopes and unifying the people in<br />

popular protest. The people would not back down. Over the<br />

next few years - buoyed by a Gorbachev-inspired relaxation<br />

of Soviet foreign policy - the Polish people continued to batter<br />

on the door of freedom.<br />

Renewed labour strikes and a faltering economy nosediving<br />

towards disaster forced Jaruzelski into initiating talks with<br />

opposition leaders in 1988, and the following year Solidarity<br />

was once more granted legal status. Participating in Poland’s<br />

first post-Communist election the party swept to victory, with<br />

former electrician Lech Wałęsa leading from the soapbox.<br />

Fittingly it was Wałęsa who unveiled a monument in Katowice<br />

to the miners killed in 1981 on the tenth anniversary of the<br />

event. Poland’s transition to a market economy has since<br />

been tough, though the signs seem to point to a bright future<br />

for Poland. Katowice itself has done much to repair the<br />

environmental damage caused in the post WWII years, and<br />

the city is once more booming, with a huge influx of foreign<br />

investment marking a reversal of the city’s recent fortunes.<br />

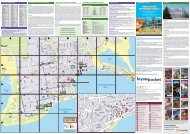

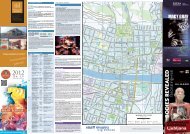

Katowice Historical Timeline<br />

1299: First recorded settlement in Silesia, ruled by<br />

Polish Silesian Piast dynasty<br />

1335: Territory becomes part of Crown of Bohemia<br />

1526: Territory passed to Austrian Habsburg Monarchy<br />

1598: First documented settlement in Katowice area<br />

1742: Territory becomes part of Prussian empire during<br />

First Silesian War<br />

1788: Area’s first mine opens<br />

1822: Katowice’s population hits 100 homestead mark<br />

1847: Railway station built<br />

1865: Municipal rights awarded to ‘Kattowitz’<br />

1871: Kattowitz is incorporated into German Empire<br />

1875: Kattowitz’s population records 11,000 residents<br />

1897: Granted rights as a city<br />

1922: Katowice becomes part of Second Polish<br />

Republic after WWI and Silesian Uprisings<br />

(1918-21). Granted autonomy by the Polish Sejm.<br />

1939: Occupied by Nazi Germany<br />

1945: Katowice is ‘Liberated’ by Soviets after WWII<br />

1953: City is renamed Stalinogród by Polish communist<br />

government<br />

1956: Former name of Katowice restored<br />

1981: Martial law declared, Wujek mine strike and massacre<br />

1983: The Pope visits Katowice<br />

1989: Party-free elections in Poland; Communist<br />

regime crumbles<br />

2004: Poland enters the European Union<br />

2006: Pigeon Fair Disaster - 65 killed and 170 injured<br />

when Katowice convention centre roof collapses<br />

2010: Polish President Lech Kaczyński and 95 other<br />

Polish delegates die in a plane crash near<br />

Smolensk, Russia, plunging the country into<br />

mourning<br />

Katowice <strong>In</strong> <strong>Your</strong> <strong>Pocket</strong> katowice.inyourpocket.com<br />

Katowice Historical Museum © Jan Mehlich<br />

The fact that Katowice hasn’t grown into a popular tourist<br />

destination can probably be explained by the brevity and<br />

slightly dubious nature of our Katowice sightseeing section<br />

- an earnest attempt to cover Katowice’s main (ahem)<br />

attractions. Nope, no castle, no palace, no hip bohemian<br />

district. No pedestrian shopping avenues, bridges or scenic<br />

riverside. Uh, no, no ancient ruins. No Old Town per say.<br />

Alas, a trip around Katowice may call to mind the old adage<br />

‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder’ (with the coal dirt and<br />

other particulates, in this case).<br />

Spodek and downtown Katowice UM Katowice<br />

No, Katowice won’t be winning any European beauty pageants,<br />

and unlike other urban casualties (hello to our friends<br />

in Warsaw), the city can’t claim to have been beaten by the<br />

Ugly Stick during World War II. No, Katowice was born with<br />

that heirloom in its hand and the Nazis probably snatched<br />

it from here as they rumbled east to the capital. And while<br />

the Soviets returned with it after the war, destroying many<br />

of the buildings on the Rynek in the 1950s to make room for<br />

their modern monuments to concrete, for example, it was<br />

predestiny that Katowice would never be belle of the ball.<br />

A blue collar city to this day, Katowice and its neighbours<br />

in Upper Silesia were born into the working class, growing<br />

up during the industrial revolution and put to work in sooty<br />

katowice.inyourpocket.com<br />

ESSENTIAL <strong>KATOWICE</strong><br />

mineshafts, factories and railway yards. The area’s history is<br />

inextricably entwined with the manufacture of coal and steel<br />

and the stacks, shafts, slagheaps and massive waves of<br />

migrants that followed the discovery of the region’s mineral<br />

resources. As such, any mention of tourism in the district is<br />

usually preceded by the word, ‘industrial.’ <strong>In</strong>deed the derelict<br />

factories and foundries, blackened chimneys and abandoned<br />

maintenance yards of Silesia’s industrial boom represent the<br />

hulking bulk of Silesia’s tourist offerings, and the region is ripe<br />

for renegade tourists eager to explore evidence of a bygone<br />

era. Those interested in industrial tourism are advised to get<br />

their creased hands on a copy of Silesia’s <strong>In</strong>dustrial Monuments<br />

Route - which can be picked up free of charge in any<br />

Silesian tourist information office - and while we’ve covered<br />

many of the entailed sites in this very guide, the region has<br />

plenty more to offer than we have space to include here.<br />

Nikiszowiec<br />

Katowice, for its part, has become a growing business centre<br />

as you’ll glean from the glittering capitalist monoliths built<br />

in recent decades. Those seeking more conventional interpretations<br />

of the word attraction will find plenty of churches<br />

including Christ the King Cathedral - the country’s largest,<br />

one of the best museums in southern Poland in the Katowice<br />

Historical Museum, and anyone paying attention will notice<br />

a number of discreetly handsome townhouses, particularly<br />

along ulica 3-go Maja between the Rynek (C-3) and Plac<br />

Wolności (C-1). Conventional charm has obviously never<br />

been a strength of Katowice, however, as best evidenced by<br />

the bonkers Spodek building (B-3) and the offbeat outland<br />

districts of Nikiszowiec and Giszowiec. The city’s most<br />

bonafide attraction is the immense Park of Culture and<br />

Recreation, which is techincally located in Chorzów. Yes, it’s<br />

always been the shaft (literally) for Katowice, and while being<br />

a tourist in this city may feel a bit like getting dressed for the<br />

theatre and ending up at a Board of Education meeting, we<br />

hope you enjoy it for its oddities, and remember that some<br />

things look most beautiful through beer goggles.<br />

Christ the King Cathedral © PetrusSilesius<br />

July - October 2012<br />

51