Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

6<br />

GROSS-ROSEN<br />

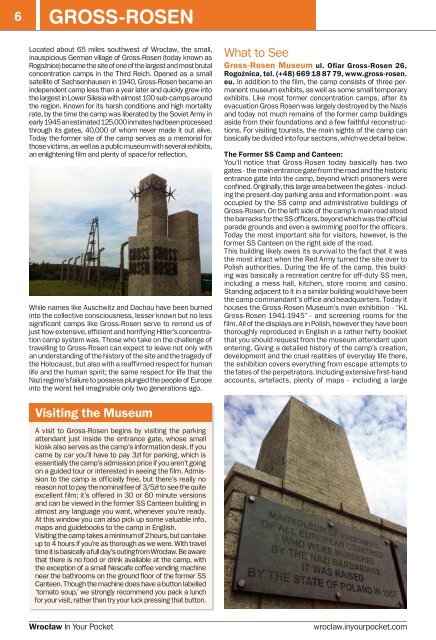

Located about 65 miles southwest of Wrocław, the small,<br />

inauspicious German village of Gross-Rosen (today known as<br />

Rogoźnice) became the site of one of the largest and most brutal<br />

concentration camps in the Third Reich. Opened as a small<br />

satellite of Sachsenhausen in 1940, Gross-Rosen became an<br />

independent camp less than a year later and quickly grew into<br />

the largest in Lower Silesia with almost 100 sub-camps around<br />

the region. Known for its harsh conditions and high mortality<br />

rate, by the time the camp was liberated by the Soviet Army in<br />

early 1945 an estimated 125,000 inmates had been processed<br />

through its gates, 40,000 of whom never made it out alive.<br />

Today the former site of the camp serves as a memorial for<br />

those victims, as well as a public museum with several exhibits,<br />

an enlightening film and plenty of space for reflection.<br />

While names like Auschwitz and Dachau have been burned<br />

into the collective consciousness, lesser known but no less<br />

significant camps like Gross-Rosen serve to remind us of<br />

just how extensive, efficient and horrifying Hitler’s concentration<br />

camp system was. Those who take on the challenge of<br />

travelling to Gross-Rosen can expect to leave not only with<br />

an understanding of the history of the site and the tragedy of<br />

the Holocaust, but also with a reaffirmed respect for human<br />

life and the human spirit; the same respect for life that the<br />

Nazi regime’s failure to possess plunged the people of Europe<br />

into the worst hell imaginable only two generations ago.<br />

Visiting the Museum<br />

A visit to Gross-Rosen begins by visiting the parking<br />

attendant just inside the entrance gate, whose small<br />

kiosk also serves as the camp’s information desk. If you<br />

came by car you’ll have to pay 3zł for parking, which is<br />

essentially the camp’s admission price if you aren’t going<br />

on a guided tour or interested in seeing the film. Admission<br />

to the camp is officially free, but there’s really no<br />

reason not to pay the nominal fee of 3/5zł to see the quite<br />

excellent film; it’s offered in 30 or 60 minute versions<br />

and can be viewed in the former SS Canteen building in<br />

almost any language you want, whenever you’re ready.<br />

At this window you can also pick up some valuable info,<br />

maps and guidebooks to the camp in English.<br />

Visiting the camp takes a minimum of 2 hours, but can take<br />

up to 4 hours if you’re as thorough as we were. With travel<br />

time it is basically a full day’s outing from Wrocław. Be aware<br />

that there is no food or drink available at the camp, with<br />

the exception of a small Nescafe coffee vending machine<br />

near the bathrooms on the ground floor of the former SS<br />

Canteen. Though the machine does have a button labelled<br />

‘tomato soup,’ we strongly recommend you pack a lunch<br />

for your visit, rather than try your luck pressing that button.<br />

What to See<br />

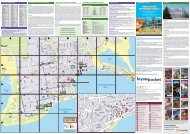

Gross-Rosen Museum ul. Ofiar Gross-Rosen 26,<br />

Rogoźnica, tel. (+48) 669 18 87 79, www.gross-rosen.<br />

eu. <strong>In</strong> addition to the film, the camp consists of three permanent<br />

museum exhibits, as well as some small temporary<br />

exhibits. Like most former concentration camps, after its<br />

evacuation Gross Rosen was largely destroyed by the Nazis<br />

and today not much remains of the former camp buildings<br />

aside from their foundations and a few faithful reconstructions.<br />

For visiting tourists, the main sights of the camp can<br />

basically be divided into four sections, which we detail below.<br />

The Former SS Camp and Canteen:<br />

You’ll notice that Gross-Rosen today basically has two<br />

gates - the main entrance gate from the road and the historic<br />

entrance gate into the camp, beyond which prisoners were<br />

confined. Originally, this large area between the gates - including<br />

the present-day parking area and information point - was<br />

occupied by the SS camp and administrative buildings of<br />

Gross-Rosen. On the left side of the camp’s main road stood<br />

the barracks for the SS officers, beyond which was the official<br />

parade grounds and even a swimming pool for the officers.<br />

Today the most important site for visitors, however, is the<br />

former SS Canteen on the right side of the road.<br />

This building likely owes its survival to the fact that it was<br />

the most intact when the Red Army turned the site over to<br />

Polish authorities. During the life of the camp, this building<br />

was basically a recreation centre for off-duty SS men,<br />

including a mess hall, kitchen, store rooms and casino.<br />

Standing adjacent to it in a similar building would have been<br />

the camp commandant’s office and headquarters. Today it<br />

houses the Gross-Rosen Museum’s main exhibition - “KL<br />

Gross-Rosen 1941-1945” - and screening rooms for the<br />

film. All of the displays are in Polish, however they have been<br />

thoroughly reproduced in English in a rather hefty booklet<br />

that you should request from the museum attendant upon<br />

entering. Giving a detailed history of the camp’s creation,<br />

development and the cruel realities of everyday life there,<br />

the exhibition covers everything from escape attempts to<br />

the fates of the perpetrators. <strong>In</strong>cluding extensive first-hand<br />

accounts, artefacts, plenty of maps - including a large<br />

Wrocław <strong>In</strong> <strong>Your</strong> <strong>Pocket</strong> wroclaw.inyourpocket.com<br />

3D scale model of the camp - and even original art made<br />

by survivors, the exhibit is highly informative and upfront<br />

without seeking sympathy . Don’t miss the shocking<br />

stained glass windows in the first room, and bear in mind<br />

that the only bathrooms in the camp are in this building<br />

(both upstairs and down); they will seem really far away if<br />

you need them later.<br />

The Quarry:<br />

Gross-Rosen owes its existence and its location to the granite<br />

quarry located directly next to the camp. ‘Quarry means<br />

death’ was the ominous phrase spoken by the camp’s<br />

prisoners, who knew they wouldn’t last long if they were<br />

assigned to work there. <strong>In</strong> the first two years of the camp,<br />

however, it was unavoidable. As the camp grew, inmates<br />

would quarry stone 12 hours a day on starvation rations<br />

while being terrorised by SS officers only to build prison<br />

barracks in the evenings. The camp’s own doctor, who went<br />

on to work in other camps later in the war, described the<br />

living conditions he saw at Gross-Rosen as worse than at<br />

other camp for the simple fact that all of the prisoners were<br />

employed in the quarry. The mortality rate was extremely<br />

high and the average lifespan of a quarry worker at Gross-<br />

Rosen was not more than 5 weeks. Make a right from in<br />

front of the Prisoners’ Camp Gate and walk up a small hill<br />

to see and reflect on this rather picturesque pit where so<br />

many men were worked to their deaths.<br />

The Prisoners’ Camp Entrance Gate:<br />

Gross-Rosen’s most iconic<br />

building is the completely<br />

restored prisoners’ camp<br />

entrance gate with its infamous,<br />

obligatory and<br />

insincere mantra Arbeit<br />

Macht Frei (‘Work Makes<br />

You Free’) emblazoned<br />

above the granite archway,<br />

beyond which there was<br />

actually almost no chance<br />

of freedom. Topped with<br />

a watchtower, flanked by<br />

two wooden guardhouses,<br />

and surrounded with what<br />

was once an electric fence, here you’ll find the museum’s<br />

other two primary exhibits. <strong>In</strong> the guardhouse on the left<br />

side is the permanent exhibit ‘Lost Humanity’ which gives<br />

a general but succinct and enlightening overview of Europe<br />

in the years 1919-1945, focussing on Hitler’s rise to power,<br />

the growth of German fascism, the origin and development<br />

of the concentration camp system - described as ‘Hitler’s<br />

extermination apparatus’ - and the plight of Poland trapped<br />

between two totalitarian regimes bent on expansion. <strong>In</strong> the<br />

guardhouse on the right side is the exhibit ‘AL Riese - Satellite<br />

Camps of the Former Concentration Camp Gross-Rosen,’<br />

which details the sub-camps of Gross-Rosen located in the<br />

Owl Mountains southwest of Wrocław along the modern-day<br />

border of Poland and Czech Republic. Established in 1943<br />

as the tide of WWII began to turn against the Third Reich,<br />

the work camps of AL Riese were created to build what many<br />

believe was to be a massive underground headquarters<br />

for Hitler. The project was eventually abandoned, but not<br />

before over 194,232 square metres of secret passageways<br />

were dug into the mountains by prisoners, some 3,648 of<br />

whom died during the work. While the exhibit does much to<br />

explain why sub-camp Riese had such a high death rate, it<br />

rather disappointingly doesn’t indulge in speculation about<br />

Hitler’s plans for the project, which remains one of WWII’s<br />

greatest mysteries. Displays in both guardhouse exhibits are<br />

presented in English, Polish, French, German and Russian.<br />

wroclaw.inyourpocket.com<br />

GROSS-ROSEN<br />

A Brief History<br />

Gross-Rosen Concentration Camp came into being<br />

on August 2nd, 1940 when a transport of prisoners<br />

was sent to the SS-owned quarry on a hill above the<br />

small German village of the same name (today known<br />

as Polish Rogoźnice) and essentially forced to begin<br />

building the camp themselves. Soon more and more<br />

prisoners were being sent and by May 1st, 1941<br />

Gross-Rosen had grown enough to gain the status of<br />

a self-reliant concentration camp. Conditions in the<br />

camp in its first two years were especially harsh with<br />

12-hour work days spent excavating granite from the<br />

quarry, insufficient food rations and violent abuse from<br />

the SS officers and staff who were actually awarded<br />

military decorations from Nazi command for inhumane<br />

treatment of the prisoners and executions. While the<br />

famous Nazi motto written above the camp’s gate<br />

and divulged to the inmates was ‘Arbeit Macht Free’<br />

(Work Makes You Free), the administration actually<br />

phrased it a different way, operating the camp under<br />

the acknowledged motto of ‘Vernichtung Durch<br />

Arbeit’ (Extermination Through Work). At the camp’s<br />

start prisoners were forbidden from receiving mailed<br />

parcels, however the administration later reckoned<br />

that changing the policy would allow them to continue<br />

serving the same starving food rations. All packages<br />

were inspected and any valuables were stolen, but<br />

food was allowed; thus, in the Nazis’ view, people in<br />

occupied countries became partly responsible for<br />

feeding the inmates. Due to the deplorable conditions,<br />

Gross-Rosen was regarded by the Nazis themselves<br />

as among the worst of all the concentration camps.<br />

An increasing emphasis on using prison labour in<br />

armaments production lead to the large expansion of<br />

Gross-Rosen in 1944, when it became the administrative<br />

hub of a vast network of at least 97 sub-camps<br />

all across Lower Silesia and the surrounding region.<br />

While several hundred Jews had been prisoners<br />

of the camp between 1940 and 1943, most of its<br />

population were Polish and Soviet POWs. However<br />

as camps further east began to be evacuated, a<br />

vast influx of Jews began to arrive in Gross-Rosen,<br />

including prisoners from Auschwitz for whom a whole<br />

new annex of the camp was built specifically in the<br />

fall of 1944. [Readers familiar with the story of Oskar<br />

Schindler may know that some of his Jewish workers<br />

were sent to Gross-Rosen on their way to Brünnlitz,<br />

which was itself a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen located<br />

in Czech Republic.] Between October 1943 and January<br />

of 1945 as many as 60,000 Jews were deported<br />

to Gross-Rosen, mostly from Poland and Hungary.<br />

Gross-Rosen also had one of the highest populations<br />

of female prisoners in the entire concentration camp<br />

system at this time.<br />

One of the last camps to be evacuated, in early February<br />

1945 the Germans forced some 40,000 prisoners,<br />

half of whom were Jews, on brutal death marches to<br />

the west which lasted days, and even weeks in some<br />

cases. With no food or water, freezing conditions,<br />

and an SS policy of shooting anyone who looked too<br />

weak to continue, many of the former inmates did not<br />

survive to freedom. Gross-Rosen was liberated by the<br />

Soviet Army on February 13, 1945. It is estimated that<br />

125,000 prisoners went through the camp, 40,000<br />

of whom perished.<br />

September - December 2012<br />

7