Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

74<br />

FESTUNG BRESLAU<br />

One of the biggest events to ever rock Wrocław, the epic<br />

80-day siege of 1945 cost tens of thousands of lives and<br />

left the town a smouldering heap of ruins. One of the most<br />

savage sieges in modern history, the ‘Battle for Breslau’ rates<br />

as one of the biggest human tragedies of WWII.<br />

Prelude<br />

Prior to WWII Wrocław, or ‘Breslau’ as it was then known, was<br />

something of a model Nazi city, with a staggering 200,000 of<br />

its citizens voting for Hitler’s NSDAP party in the 1933 elections.<br />

From that moment on the Nazis cemented their grip on the city<br />

launching a campaign of terror, and eventually murder, against<br />

Jews and numerous other enemies of the state. Synagogues<br />

were burnt to the ground on Kristallnacht - November 9, 1938<br />

- and the guillotine at Kleczkowska prison saw plenty of action,<br />

with the decapitated bodies of political prisoners donated to<br />

Wrocław’s medical schools. Yet in spite of this sinister background<br />

and strict rationing the citizens of wartime Wrocław<br />

fared better than their compatriots elsewhere in the Reich. Out<br />

of range from Allied air raids local denizens were spared the<br />

aerial nightmare of British carpet bombings, and the city came<br />

to be considered something of a safe haven, its population<br />

swelling to over a million people towards the end of the conflict.<br />

However, by the second half of 1944 the doomsday reality<br />

of war started to dawn on the local population. Truckloads<br />

of mangled German wounded flooded the hospitals, and with<br />

the Red Army creeping closer the rumble of artillery could be<br />

heard in the distance. On August 24 the city was declared a<br />

closed stronghold, ‘Festung Breslau’, and the citizens braced<br />

themselves for the inevitable bloodbath that was to come.<br />

General Johann Krause was appointed commander, and set<br />

about the daunting task of turning a picture-book city into<br />

a fortress. Two defensive rings were constructed around<br />

the city (with some fortifications 20km outside the centre),<br />

supplies were stockpiled and troops mobilised. A garrison of<br />

some 80,000 men was hurriedly raised in what was projected<br />

to become the key defensive element on ‘The Eastern Wall’. <strong>In</strong><br />

reality, however, the troops were a chaotic rabble consisting<br />

of Hitler Youth, WWI veterans, police officers and retreating<br />

regiments. This mixed bag of men and boys were ludicrously<br />

ill-equipped to face the full force of the looming Soviet fury.<br />

As countdown to the impending siege began the governor<br />

of the region, Gauleiter Karl Hanke, noted he only had two<br />

tanks at his disposal, and weaponry that was either outdated<br />

or captured from previous campaigns in Poland, Russia and<br />

Yugoslavia. Even so, Hanke stubbornly refused to order an<br />

evacuation of civilians until January 19, 1945. By this time<br />

the majority of transport links had been smashed by Soviet<br />

shelling, forcing many evacuees to leave the city on foot.<br />

With temperatures sinking to -15˚C, an estimated 100,000<br />

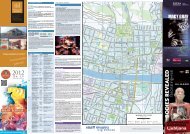

The Soviet Cemetery on Skowronia Góra A. Webber<br />

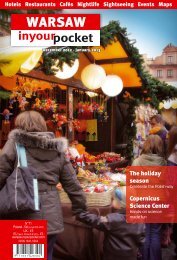

A bunker near Partisan Hill used temporarily as Nazi<br />

headquarters during the Siege A. Webber<br />

people froze to death during this ill-fated evacuation, with<br />

other reports of children trampled to death in the chaos<br />

that ensued at the train station. Wrocław was in a state of<br />

full-blown panic. Defeatism was punished by death and on<br />

January 28 the deputy mayor, Dr. Wolfgang Spielhagen, was<br />

executed in the main square for this very reason. Execution<br />

squads roamed the city, murdering pessimists, looters and<br />

anyone found shirking their duty to the Fatherland. Finally,<br />

following a rapid advance, the advancing Soviets encircled<br />

the city on February 15, 1945. Wrocław’s fate was sealed.<br />

Siege<br />

On February 16, 1945 months of waiting finally came to an<br />

end. The Red Army launched a ferocious attack on the city,<br />

throwing hundreds of tanks into the fray. But hopes for a quick<br />

victory proved optimistic, and the battle soon turned into a<br />

brutal slaughter, with both sides sustaining heavy casualties.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the first three days alone the Soviets lost well over 70 tanks<br />

as the conflict descended into savage street fighting. <strong>In</strong> his<br />

excellent book, Microcosm, author Norman Davies suggests<br />

that as a last resort measure chemical weapons produced in<br />

Silesia were used to repel Soviet troops in the early stages of<br />

combat, though this theory is largely open to debate. Civilians<br />

and slave labour were called up to build fortifications, and vast<br />

stretches of the city were demolished so bricks could be used<br />

to strengthen defences. <strong>In</strong> a growing sign of desperation even<br />

the University Library found itself stripped of thousands of<br />

books, all destined for the barricades. <strong>In</strong> March the residential<br />

area between the Szczytnicki and Grunwaldzki bridges was<br />

levelled in order to build an improvised airstrip that would, in<br />

theory, be Breslau’s connection to the outside world. The enormous<br />

project was a disaster. With rations only issued to those<br />

working, civilians were forced to work under fierce fire and as<br />

a result over 13,000 died when the Soviets shelled the area.<br />

But worse was to come. April 1 saw the Soviets launch a new<br />

offensive to seize the city. A heavy bombardment saw much of<br />

the city engulfed in flames, and hostilities were resumed once<br />

more. With the noose tightening, Nazi HQ relocated from the<br />

bunker on Partisan Hill to the University Library, while fighting<br />

continued to rage in the sewers and houses on the fringes of<br />

the city. Even with the end in sight, the Nazis fought bitterly to<br />

the last man, crushing an ill-fated uprising by the remaining<br />

civilians. A full five days after the Battle for Berlin had ended,<br />

Breslau finally capitulated on May 6, the peace deal signed at<br />

the villa on ul. Rapackiego 14. The day before Karl Hanke, the<br />

very man who had ordered the execution of anyone caught<br />

fleeing the city, escaped the city in a plane apparently bound for<br />

the Czech Republic. What became of him remains a mystery.<br />

Wrocław <strong>In</strong> <strong>Your</strong> <strong>Pocket</strong> wroclaw.inyourpocket.com<br />

Aftermath<br />

For the survivors the end of the war unleashed a new enemy.<br />

It’s estimated that approximately two million German women<br />

were raped by Red Army soldiers, and Breslau proved no<br />

exception as marauding packs of drunken troops sought to<br />

celebrate the victory. With all hospitals destroyed, and the<br />

city waterworks a pile of ruins, epidemics raged unchecked<br />

as the city descended further into a hellish chaos. Historical<br />

figures suggest that in total the Battle for Breslau cost the<br />

lives of 170,000 civilians: 6,000 German troops, and 7,000<br />

Russian. 70% of the city lay in total ruin (about 75% of that<br />

directly attributed to Nazi efforts to fortify the city), 10km of<br />

sewers had been dynamited and nearly 70% of electricity cut<br />

off. Of the 30,000 registered buildings in Wrocław, 21,600<br />

sustained damage, with an estimated 18 million cubic metres<br />

of smashed rubble covering the city – the removal of this<br />

war debris was to last until the 1960s. Although several<br />

bunkers still lie scattered around the city (Park Zachodni,<br />

Park Południowy, etc.) there is no official memorial for the<br />

thousands of innocent victims of war. Two Soviet cemeteries<br />

stand in the suburbs: one for officers on ul. Karkonoska,<br />

and one for the rank and file on Skowronia Góra. Both find<br />

themselves in state of disrepair, littered with broken glass<br />

and graffiti. A German military cemetery and Garden of Peace<br />

can be found 15 kilometres from Wrocław, the final resting<br />

place of approximately 18,000 soldiers.<br />

Declared a part of Poland under the terms of the Yalta<br />

Agreement the new rulers of Wrocław arrived three days<br />

after the peace deal. A new chapter in Wrocław’s history<br />

was about to be written. Poles from the east flocked to<br />

repopulate Wrocław, swayed by rumours of jobs, wealth<br />

and undamaged townhouses. Over ten per cent of these<br />

new settlers hailed from the eastern city of Lwow (now<br />

Ukrainian L’viv) and this mass migration was to irrevocably<br />

change Wrocław’s demographic makeup. Others hailed<br />

from impoverished villages, with their peasant mentality<br />

frequently blamed for harming surviving city structures:<br />

‘heaps of coal in a bathtub, hens in an expensive piano<br />

and a pig kept on the fourth floor of an apartment were<br />

not rare exceptions’, so writes Beata Maciejewska in her<br />

excellent book ‘Wrocław: History of the City’. But farm<br />

Further Reading<br />

Microcosm: Portrait of a Central European City<br />

By Norman Davies & Roger Moorehouse<br />

An excellent, encyclopaedic and engrossing book by<br />

Davies, the guru of Polish history writing. With Wrocław<br />

as the central character, Davies demonstrates how the<br />

city both affects and is effected by the whirlwind events<br />

of European history, resulting in it changing ownership,<br />

name and size more times than any other city on the<br />

continent. <strong>In</strong> Davies’ view, no city is better suited to<br />

represent the Central European experience as its<br />

unique geographical position has conspired to make it<br />

a ‘microcosm’ and melting pot of the myriad European<br />

concerns and conditions throughout the centuries. It’s<br />

a convincingly made argument, as over an exhaustive<br />

600-some pages Davies details the history of Central<br />

Europe without ever taking the action out of Wrocław.<br />

Starting with a horrific description of the annihilation of<br />

Fortress Breslau in the prologue, and including plenty of<br />

gory details of medieval urban life, if you want to read one<br />

book about Wrocław other than the one in your hands,<br />

make it this one.<br />

[ISBN 0-224-06243-3, price approx. 100zł.]<br />

wroclaw.inyourpocket.com<br />

FESTUNG BRESLAU<br />

Memorial in the Soviet Cemetery on Skowronia Góra<br />

A. Webber<br />

animals eating sofas were the least of the city’s worries.<br />

Wrocław was on the brink of anarchy, with armed gangs of<br />

Russians, Germans and Poles roaming the streets at night,<br />

looting, shooting and boozing. Fortunes were made from<br />

theft, with most goods ending up in the open air bazaar<br />

that had sprung up on Pl. Grunwaldzki; Maciejewska’s<br />

research reveals this was the source of everything from<br />

railway wagons loaded with bricks, to priceless paintings<br />

dating from the 17th century. Black market trading thrived,<br />

and the money that was flying round led to a slew of bars<br />

and ballrooms opening, many with colourful names: Kiosk<br />

Pod Bombą (Kiosk Under the Bomb) and Wstąp Kolego na<br />

Jednego (Drop <strong>In</strong> For a Drink, Mate) being a couple of note.<br />

The end of the war also signalled an active campaign to<br />

de-Germanize the city. Newspapers launched competitions<br />

to eliminate all traces of Wrocław’s German heritage<br />

with monuments and street signs all falling victim to this<br />

iconoclastic fury. By the end of 1945 as many as 300,000<br />

Germans were still in the city, many of whom had been<br />

temporarily relocated from Poznań, and this was a pressing<br />

concern for the Polish authorities. Forced transports<br />

began in July, and by January 1948 Wrocław was officially<br />

declared to be free of German habitants (there were, in fact,<br />

still 3,000 in the city, essentially kept on to do jobs Poles<br />

were unqualified for).<br />

Wrocław was chosen to host the Exhibition of Recovered Territories,<br />

a propaganda stunt aimed at highlighting the glories<br />

of Polish socialism. Attracting over 1.5 million visitors the<br />

exhibition finally closed in 1948, and with that investment and<br />

national interest in Wrocław died. For the next few years the<br />

city was to become a feeder city for Warsaw, with priceless<br />

works of art ferried to the capital. <strong>In</strong> 1949 approximately<br />

200,000 bricks were sent daily up to Warsaw, with several<br />

undamaged buildings falling victim to the demolition teams<br />

hell-bent on rebuilding the Polish capital. Wrocław’s recovery<br />

was still a long way away.<br />

September - December 2012<br />

75